Ria

Rita

Andre

Yiping

Ria

Rita

Andre

Yiping

As this report discusses, critical barriers to health access and equity exist in New Mexico, due to the lack of trust, staggering health disparities, and inadequate service delivery in indigenous communities. We recognize that the relationship between government entities and indigenous communities is complex and painful, with a long history of broken promises and mistrust. We specifically want to recognize this harsh reality in the context of Princeton University’s role in the Manhattan Project, which produced the world’s first nuclear weapons during the Second World War.

At the time, the U.S. government recruited talented scientists in institutions of higher learning throughout the country, and professors from Princeton University in physics and chemistry joined the project as consultants.1 Members of the Navajo Nation and the Southwest Pueblos in New Mexico were displaced from their lands for the creation of what became the Los Alamos National Laboratory and for uranium mining needed during the project.2

After the Trinity Test which marked the first detonation of an atomic bomb, people in the State of New Mexico who were exposed to the radiation fallout experienced health issues as a result of exposure and contamination. As we studied health inequities that persist among indigenous communities in New Mexico as part of our evaluation of the Native American Premium Assistance Program (NAPA), we acknowledge that both the effects of nuclear testing and the efforts of the project itself have led to environmental and health impacts in the area. This history of nuclear tests may have furthered health inequities and overall mistrust among indigenous communities.

“We recognize that the relationship between government entities and indig enous communities is complex and painful, with a long history of broken promises and mistrust.

We wish to clarify that this statement does not reflect the views of Princeton University, the Princeton School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University staff or administrators, or the State of New Mexico, and are the collective opinion of the nine students who co-authored this report.

Respectfully,

Mary Grace Darmody

Ria Hanson

Laura Hausman

Rita Fernandez

Andre Jimenez

Yiping Li

Raj Mukherji

Brontë Nevins

Gillian Tisdale

This report was prepared by graduate students at Princeton’s School of Public and International Affairs. The report incorporates research, data analysis, and insights from interviews, most of which were conducted in New Mexico from October 16 – October 20, 2023. We are grateful to New Mexico’s Office of the Superintendent of Insurance for the opportunity to collaborate on this project.

This report fulfills Princeton’s graduate requirements for the Master in Public Affairs degree, which requires that all students conduct research and produce an actionable policy proposal for a client. We wish to express our gratitude to our instructors Heather Howard and Dan Meuse, who were so generous with their time, insights, and experience throughout the course of this project. We also wish to thank the many topic experts and contacts in New Mexico who shared their valuable perspectives with us as we created this report.

Secretary Kari Armijo, Cabinet Secretary, Human Services Department

Nick Autio, General Counsel, New Mexico Medical Society

Colin Baillio, Deputy Superintendent of Insurance, New Mexico Office of the Superintendent of Insurance

Sara Bencic, Colorado Option Director, Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies

Tom Betlach, former Arizona Medicaid Director

Nathan Bush, Director of Government Relations, The University of New Mexico

Cynthia Cisneros, Public Outreach Coordinator, New Mexico Office of the Superintendent of Insurance

Troy Clark, Chief Executive Officer, NM Hospital Association

Nick Cordova, Healthcare Director, New Mexico Center on Law and Poverty

Brent Earnest, Chief Operating Officer, beWellnm

RubyAnn Esquibel, University of New Mexico Health System

Bruce Gilbert, Chief Executive Officer, beWellnm

Sahar Hassanin, Economist, New Mexico Office of the Superintendent of Insurance

Bill Jordan, Interim Co-Director and Government Relations Officer, New Mexico Voices for Children

Annie Jung, Executive Director, New Mexico Medical Society

Loreli Kellogg, Acting Medicaid Director, New Mexico Human Services Department

Pamela Kirby Blackwell, Director of Government Relations and Communications, NM Hospital Association

Jessica Lopez Collins, New Mexico Program Director, Forward Together

Juliette McCoy Program Manager of Population Health, Presbyterian Healthcare Services

Carrie Robin Brunder, Chief Lobbyist, New Mexico Medical Society

Chrissy Robinson, Program Coordinator, New Mexico Office of the Superintendent of Insurance

Maria Rodriguez, Health Equity & Outreach Specialist, Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies

Javier Rojo, Senior Research and Policy Analyst, New Mexico Voices for Children

Julia Ruetten, Director of Government Regulation and Reimbursement Policy, NM Hospital Association

Alex Sanchez, Director of Communications, beWellnm

Divya Shiv, Research and Policy Analyst, New Mexico Voices for Children

Jacqueline Smith, Director of Public Policy and Government Relations, Presbyterian Healthcare Services

Rep. Reena Szczepanski, Majority Whip, New Mexico House of Representatives

Barbara Webber, Executive Director, Health Action New Mexico

This report was prepared for New Mexico’s Office of the Superintendent of Insurance (OSI) as the state seeks to boost health insurance coverage and make transformational investments in access to high-quality, affordable health care. New Mexico’s efforts come at a critical juncture; the impacts of COVID-19 and the Medicaid “unwinding” process have exacerbated issues in the health landscape for providers and patients alike. At the request of OSI, this report evaluates:

1. Health access and cost issues in New Mexico (based on available literature, stakeholder interviews, and OSI survey data) and pathways to address these issues

2. The health equity impact of various policy initiatives and recommendations for future implementation, including:3

a. The Native American Premium Assistance program (NAPA)

b. The Coverage Expansion Plan (CEP)

c. Medicaid Forward, and

3. Policies that OSI could adopt to address provider shortage issues in New Mexico.

New Mexico’s health care landscape presents several overarching challenges for coverage and health access. First, the state is among the most rural in the nation; ensuring provider access in sparsely populated areas remains a key challenge. Second, high premiums and out-of-pocket costs can make plans on New Mexico’s exchange, beWellnm, unaffordable for many who do not qualify for Medicaid due to income thresholds or immigration status. Additionally, indigenous and undocumented communities in New Mexico face unique barriers to access. Uptake of Medicaid and marketplace plans (which are often required to supplement care at Indian Health Service facilities) has been low in indigenous communities, due to historic mistrust and barriers to ongoing outreach. Undocumented residents, meanwhile, cannot access care on either Medicaid or New Mexico’s marketplace; care is only available via the New Mexico Medical Insurance Pool (NMMIP) and private markets, both of which can be unaffordable.

The state has implemented and proposed various ideas to address these issues and improve health access. This report focuses specifically on NAPA, CEP, and Medicaid Forward, before discussing ways to approach New Mexico’s provider shortage. Insights and recommendations related to these proposals are based on data analysis, literature reviews, and stakeholder interviews with advocates, legislators, state officials, providers, and carriers.

NAPA aims to enhance the affordability of marketplace plans for indigenous New Mexicans by offering zero-dollar premiums for individuals below 300% of the federal poverty level (FPL) and reduced premiums for those earning below 400% FPL. This supplement to the Indian Health Service (IHS) is critical, as it provides access to care beyond what the IHS can offer, particularly for indigenous New Mexicans living or commuting outside of reservation territory. Despite its potential, NAPA has seen limited enrollment during initial implementation. At the time of writing, approximately 1,000 indigenous New Mexicans participated, a small fraction of the state’s indigenous population. Language barriers, limited outreach, and a pervasive distrust in government programs among indigenous communities all limit enrollment.

A strategic shift in outreach and implementation can improve NAPA’s effectiveness. Opportunities exist to prioritize relationship-building with tribal communities and to leverage existing community programs that have already built trust with pueblos. The state should clearly communicate the specific benefits of NAPA, especially in relation to the services provided by (and limitations of) IHS. Furthermore, ensuring the continuity of NAPA’s funding will be vital to improving access and fostering trust with indigenous communities over time.

CEP is a key initiative to cover uninsured individuals who do not have access to other, affordable coverage options, most likely due to immigration status. The plan targets residents earning up to 200% FPL and similar to New Mexico’s Medicaid program, will cover essential health benefits. Individuals with incomes up to 138% FPL will not pay a deductible or premium, whereas individuals with incomes between 138-200% FPL will pay a modest deductible.

CEP is expected to attract between 6,250 and 12,000 new enrollees in its first year, assuming 25-40% of eligible individuals enroll. Effective outreach and enrollment processes are critical to the success of CEP. New Mexico should collaborate with beWellnm to integrate enrollment, conduct outreach and education with communities, and provide robust customer support and language access resources. Successful implementation hinges on managing administrative burden, ensuring sustainable funding, and conducting comprehensive stakeholder engagement. If optimally implemented, CEP could meaningfully reduce uninsurance in New Mexico, improving overall health equity in the state.

Medicaid Forward has been proposed by lawmakers to expand health access and reduce uninsurance in New Mexico. The program would raise the current income cutoff for Medicaid eligibility (138% FPL) and could cover New Mexicans with incomes up to 400% FPL or more. Medicaid Forward would also be available to all residents, regardless of their immigration status. Early estimates from the Urban Institute suggest that Medicaid Forward could reduce the state’s uninsurance rate from 13.1% to approximately 5.75% and is anticipated to enhance the member experience by reducing insurance churn and offering stable, reliable coverage.

The legislature passed HB 400 in 2023, which commissioned a study to assess the potential impacts of Medicaid Forward. This study will likely address different implementation strategies, necessary adjustments in provider reimbursement, funding sources, and coverage eligibility. Successful implementation of Medicaid Forward could make New Mexico’s health care system more equitable and could significantly benefit residents who have been excluded from public coverage under current parameters. For the effective implementation of Medicaid Forward, several key considerations have been highlighted. These include ensuring sustainable funding, careful consideration of impacts on existing providers and provider networks and insurers, and taking care to avoid unintended consequences. The report also recommends continuous evaluation and adjustment of the program to meet evolving health care needs and to navigate the dynamic federal regulatory environment.

Provider scarcity is a critical issue in New Mexico, particularly in rural and underserved areas, as discussed in the Health Access subsection of the report. Although shortages exist across the entire health care system, provider scarcity is particularly acute in primary care and mental health services. Provider scarcity negatively impacts health access and quality for all of New Mexico’s residents, and exacerbates health disparities among rural, indigenous, and low-income communities. The rural nature of New Mexico, combined with socioeconomic challenges and gaps in broadband coverage (which impede telehealth delivery) all pose challenges to provider access.

The report discusses a series of policy recommendations to address provider shortages. Shortterm solutions include increasing reimbursement rates, addressing medical malpractice premiums, and streamlining credentialing processes for providers entering the state. Other solutions could include creating a limited license process for foreign-trained physicians; expanding graduate medical education (GME) and residency programs, particularly in underserved specialties and areas; and enhancing post-residency retention through incentives such as enhanced loan forgiveness. Implementing these strategies will require collaboration among policymakers, medical schools, and health care organizations, to address the growing urgency of ensuring access to providers for New Mexico’s residents.

As New Mexico emerges from COVID-19, the state is making a concerted effort to advance equal access to high-quality, affordable health care. Several initiatives that address health access and affordability are at different stages of discussion and implementation, including NAPA, CEP, and Medicaid Forward. To be effective, these initiatives require buy-in from a broad array of stakeholders, including legislators, advocacy organizations, providers and carriers, and the state agencies charged with implementation.

As discussed, this report 1) analyzes the current landscape of health access and affordability in New Mexico 2) evaluates the health equity impacts of NAPA, CEP, and Medicaid Forward, and 3) makes recommendations to address New Mexico’s provider shortage. Recommendations related to these topics are informed by data provided by OSI, independent research based on available literature, and conversations with stakeholders across New Mexico’s health care ecosystem. The perspectives of legislators, state agencies, providers, carriers, and health advocates all informed this report. Additionally, we conducted interviews with health care policymakers from neighboring states (Colorado and Arizona) to learn from their experiences.

Health equity, access, and affordability are critical themes that emerge repeatedly throughout this report. Accordingly, the following background section defines these concepts and applies them to the unique health care environment in New Mexico.

“Gun violence is a public health issue. Poverty is a public health issue. Environmental consequences from energy is a [sic] public health issue. [...] All of these disenfranchised populations, all of the equity barriers, are all public health issues. And when we address those, our economy is better, our families are stronger, our risks are fewer.” - Govenor Michelle Lujan Grisham5

According to the New Mexico Office of Health Equity, health equity is achieved when people of all identities, backgrounds, and geographic locations have the same opportunity to be as healthy as possible.6

Health equity is the goal; health disparities are how we measure it. Disparities are avoidable, unjust differences between health outcomes, and inequities are their underlying causes.7 Although disparities may arise in the health care system based on differences in access to and affordability of care, they also arise upstream, resulting from structural inequities embedded in previous and ongoing policies. These disparities manifest in inequitable opportunities for nutrition, public safety, housing, education, and employment. As Governor Lujan Grisham states in the quote above, health impacts all aspects of life, and myriad social and economic conditions impact health.

We believe that OSI is well-positioned to address some factors that impact health equity –specifically, disparities in health care access and affordability. Accordingly, this report focuses on how OSI can advance access and affordability for a selection of underserved populations: indigenous communities, uninsured individuals who do not have access to other coverage options, and lower-income families. The following sections illustrate the different experiences of access and affordability faced by these communities, and proposes policy solutions to close these gaps.

New Mexico is home to a diverse population of residents. According to the United States Census Bureau, the state’s population was approximately 2,117,522 as of July 2022. Among New Mexicans, 50.2% of the population identifies as Hispanic or Latino, 11.2% as Native American or Alaskan Native, 35.7% as White alone, 2.7% as Black or African American alone, 2.0% as Asian alone, and 0.02% as Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander.8 As will be discussed, New Mexico is predominantly rural, and many of the state’s residents are geographically dispersed.

Twenty-three tribes and Pueblos are located in New Mexico, including several Apache tribes and the Navajo Nation. These indigenous communities comprise slightly over 11% of the state population, per the U.S. Census.9 It should be noted, however, that there was an undercount of indigenous individuals living in reservations during the 2020 Census.10

In 2021, New Mexico’s median household income was $54,020; per capita income, however, was $29,624 in the same year. New Mexico’s median household income was substantially lower than the national median real household income ($74,580 in 2022)11. Although approximately 17.6% of the state’s population lives below the poverty line, New Mexico’s unemployment rate was 3.7% in September 2023, slightly lower than the national rate as of October 2023.12

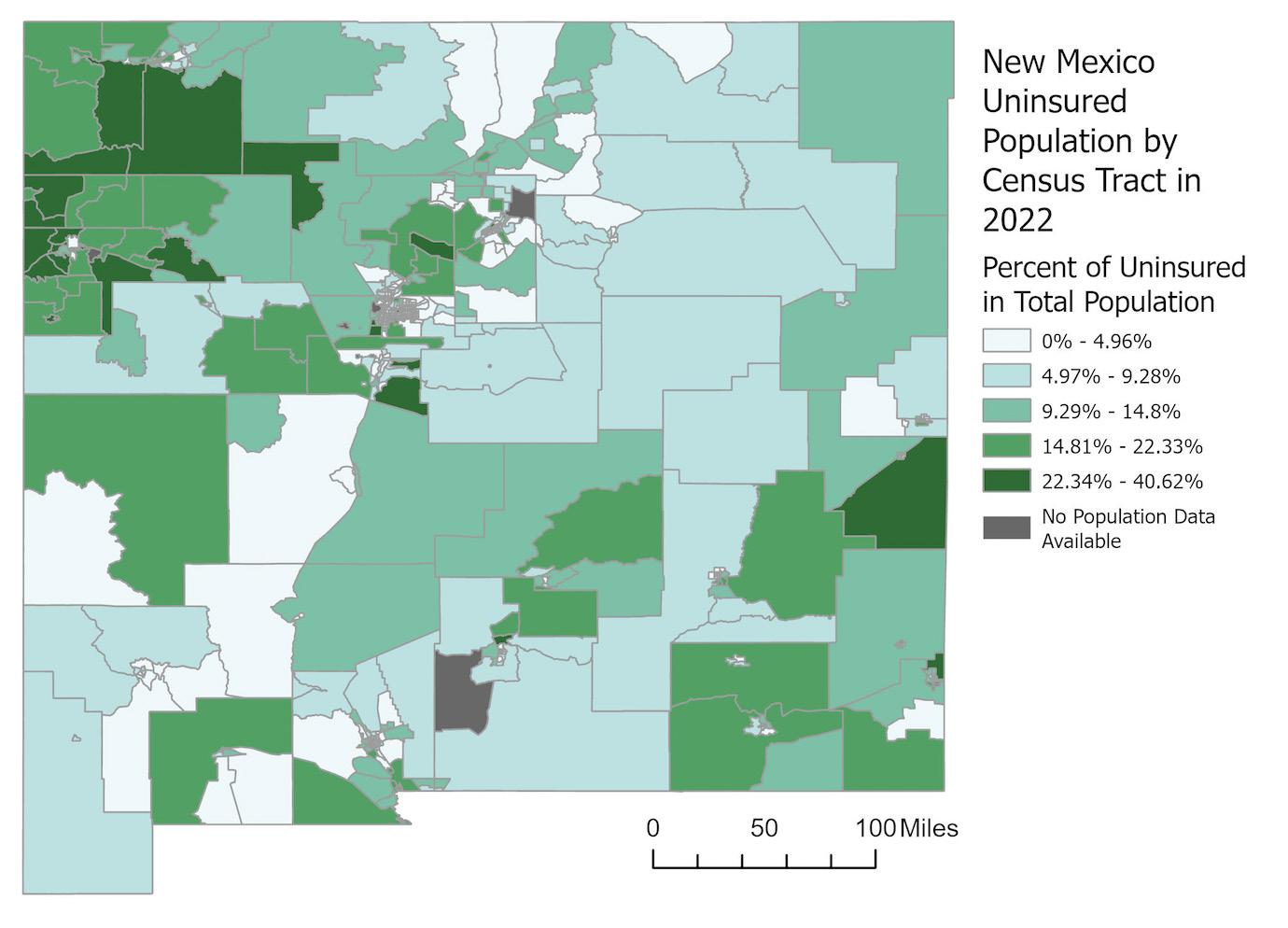

New Mexico has made significant progress in insuring the state’s population since the ACA was enacted in 2010. Nevertheless, approximately 10% of the state’s population remains uninsured.13 New Mexicans who are insured rely on a mix of coverage. In 2022, 36% of New Mexicans obtained coverage through their employers, 33.5% through Medicaid, 15.8% through Medicare, and 3.2% through the military.14

Rural Communities

New Mexico is the nation’s fifth-largest state by land area, but fifth-smallest state in terms of population.15, 16 With roughly 2,100,000 residents, New Mexico ranks 46th in population density. The combination of an expansive geographic area and a relatively diffuse distribution of residents presents formidable challenges in providing equal access to affordable and highquality health care. The New Mexico Department of Health’s Indicator-Based Information System (IBIS) defines 26 of New Mexico’s 33 counties as non-urban.17 Roughly one third of the state’s population resides in these rural or frontier areas.18

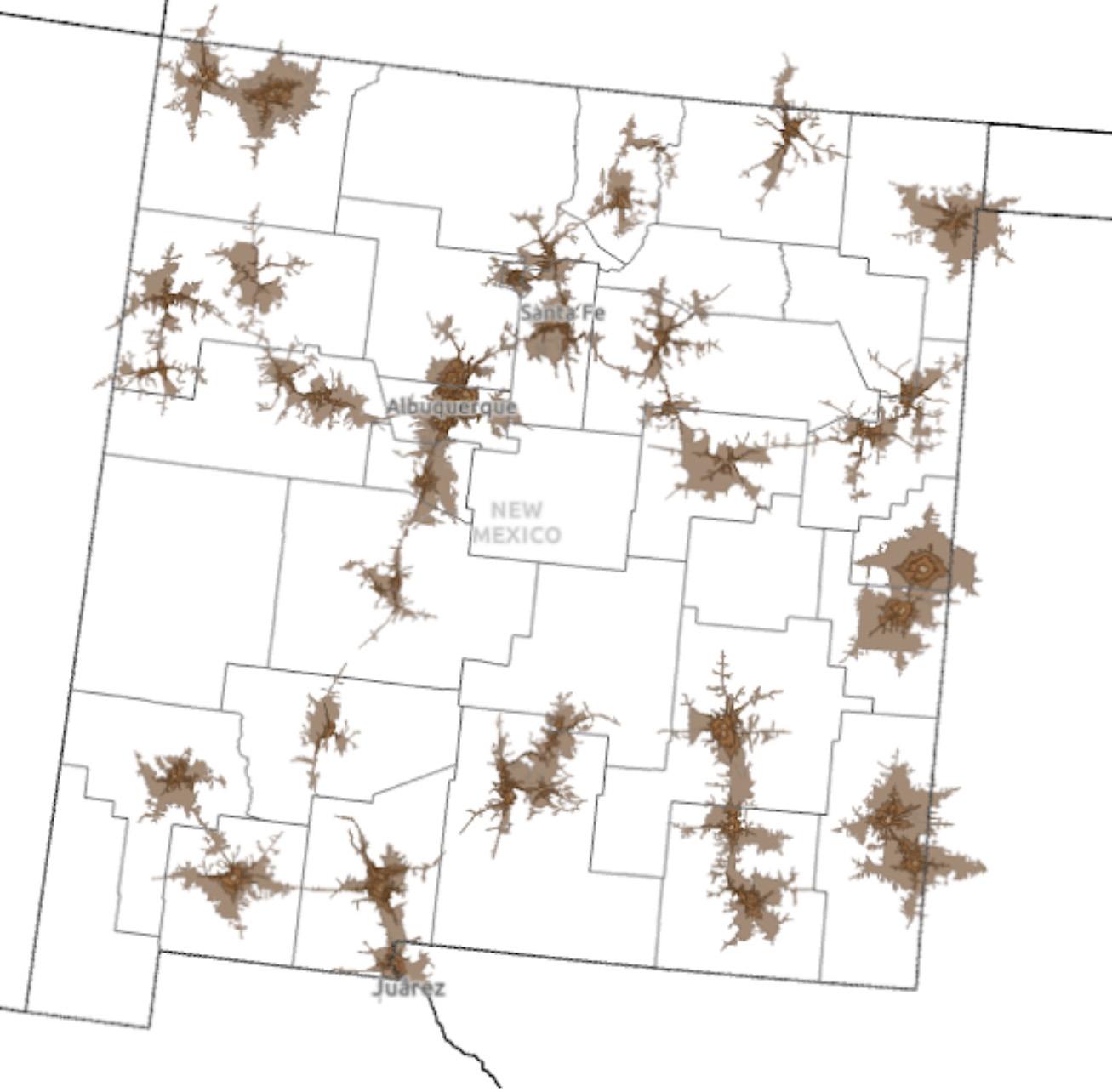

Rural and frontier areas are underserved in many ways. Critically, of the nearly 25% of New Mexican households which lack reliable internet access, a disproportionately large share reside in rural and frontier areas. This inhibits access to medical care, as digital access is critical to enrolling in health insurance, booking medical appointments, and accessing any form of telehealth services. Nearly 60% of McKinley County residents, for example, do not have broadband access.19 Some rural and frontier areas that are designated as tribal lands, furthermore, lack basic and essential services, including running water.20

Finally, rural and frontier areas suffer from a dire shortage of providers. The Health Resources and Service Administration uses the term “Healthcare Provider Shortage Areas” (HPSAs) to identify areas with a shortage of primary, dental or mental health care providers. HPSAs can be geographic areas, populations, or facilities.21

There are three types of geographic and population HPSAs for primary care: whole county, sub-county, and low-income population (the population of a county or sub-county that is below 200% FPL). All of New Mexico’s 14 Small Town Rural counties are whole-county primary care HPSAs. Of New Mexico’s 14 Large Town Rural counties, five are whole-county HPSAs and seven whole counties have a low-income population designation. By contrast, only one of New Mexico’s three Small Metro Counties has a whole-county primary care HPSA.22, 23

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Source: HRSA, U.S. Census

Compared to urban areas, rural regions have higher poverty rates, higher unemployment, and greater uninsurance.24 These deep disparities affect every corner and chapter of life. Rural regions have a lower life expectancy, more years of life lost to premature death before age 75, and disability rates that are over 20% higher than those in urban areas. Rural areas also have a 50% higher adolescent birth rate, a higher rate of preterm births, and a lower rate of births with first trimester prenatal care.25

The health disparities experienced by indigenous people stem from “the negative impacts of colonization.”26 Tribes have endured forced assimilation, removal from tribal homelands, and relocation to reservation lands. This history has contributed to an environment of distrust between indigenous communities and

the state of New Mexico, which makes it challenging to promote enrollment in services such as Medicaid and the beWellnm marketplace.

One direct threat to health is inadequate access to health care providers, due in large part to the continued underfunding of IHS. In 2018, IHS had a 30% vacancy rate across all providers for the Albuquerque and Navajo regions, with a 45-52% vacancy rate for physicians.27 Another ongoing threat is the lack of access to culturally competent care, as accessing non-indigenous providers may create linguistic barriers to obtaining high-quality care and many communities look to tribal healing in a manner that is integrated with Western medicine.

A significant portion of uninsured individuals who lack access to alternative coverage options in New Mexico are believed to be undocumented residents; these individuals may encounter distinct barriers to health access. Under federal law, undocumented residents are ineligible for traditional Medicaid regardless of income; Medicaid is restricted to U.S. citizens or certain qualified non-citizens, such as lawful permanent residents outside of the five-year bar, discussed below.28 Undocumented residents also cannot obtain coverage on the marketplace and do not qualify for federal subsidies.

More broadly, undocumented residents face legal barriers to accessing federal public benefits under the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) of 1996.29 This law established strict eligibility criteria for immigrants seeking public assistance and it bars undocumented immigrants from most federally-funded public benefits.

The five-year bar applies to documented immigrants who became ‘qualified immigrants’ within the last five years. Immigrants in the five-year bar are ineligible for federal meanstested programs, including Medicaid, CHIP, SSI, and SNAP. Individuals subject to the fiveyear bar, however, are eligible to purchase coverage on the marketplace; the Affordable Care Act’s marketplaces extend coverage to most lawfully present noncitizens. A special rule exists that permits immigrants with incomes below 100% FPL to access subsidized marketplace coverage, which is often needed in cases where immigration status renders individuals ineligible for Medicaid.30

Furthermore, the risk of becoming a “public charge” – meaning an individual who is likely to become primarily dependent on the government for subsistence – is a potential deterrent to undocumented immigrants accessing public benefits. In 2019, President Trump’s administration issued a Public Charge Rule that expanded the criteria for determining whether an immigrant applying for a visa or seeking adjustment of status (such as obtaining a green card) would be considered a “public charge.” Although this rule was struck down in several courts and removed from the federal register in 2021, this rule change has had a chilling effect on the immigrant community, further increasing the barriers to obtaining health care coverage.31 Undocumented immigrants and mixed-status families (who have individual family members that are undocumented) can be reluctant to seek services they are eligible for, out of fear that they will be identified to the federal government or could face penalties for using public benefits.

The result of this policy environment is that affordable health insurance is often inaccessible for most undocumented New Mexicans. Undocumented immigrants have the option of purchasing coverage via NMMIP or pursuing private options, which are expensive and have their own barriers to access. These barriers to insurance access create profound health disparities, as they deter individuals from seeking maintenance medication and preventative services. We heard

from stakeholders in New Mexico that undocumented individuals often only seek emergency care, resulting in higher rates of disability and health disparities.

Health affordability includes a variety of costs that increase the price of accessing health care services. Costs related to insurance (premiums, deductibles), out-of-pocket costs charged by health care facilities (copayments and coinsurance), time off from work, and transit all impact health affordability.32 These different costs accrued in accessing health services, therefore, are important factors to consider for all New Mexicans.

Health affordability is a pressing challenge in New Mexico, where 17.8% of the state’s population lived at or below the federal poverty level in 2022.33 Among the fifty states, only Louisiana and Mississippi reported higher proportions of individuals at or below the federal poverty level. Public health insurance provides a critical safety net for low-income New Mexicans; 51.2% of the state’s population relied on public coverage in 2022, the highest proportion in the nation.34

For New Mexicans with incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid, premiums and out-ofpocket costs may be unaffordable. Although the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act included financial assistance to make marketplace coverage more affordable, these enhanced subsidies are scheduled to expire after 2025, which would raise the cost of insurance for many.35 Even with this assistance, 56% of respondents in a 2022 survey reported foregoing medical care in the past two years due to cost.36 When New Mexicans do seek medical care, the ensuing bills are often prohibitive. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau reported that ~18% of New Mexicans had medical debt in 2022.37 This debt summed to approximately $881 million, or $2,692 per individual, creating a substantial financial burden on the state’s residents.

Indigenous people have treaty rights to health care from the US federal government, which is primarily supplied via IHS.38 Despite this, the underfunding of IHS leads to significant medical debt for indigenous individuals. Limited success in insuring the indigenous community through Medicaid and the beWellnm marketplace exacerbates cost barriers by putting more financial strain on IHS, which would otherwise be reimbursed by Medicaid and private payers. Furthermore, some indigenous individuals are unable to access care at IHS facilities due to geographic distance or service availability. The consensus from the stakeholders we interviewed is that more effective outreach is required to enroll indigenous communities into marketplace plans. Even then, plans may still straddle indigenous people with considerable costs associated with deductibles, coinsurance, and copays, leaving them vulnerable to acquiring medical debt.

Among uninsured individuals without access to other coverage options, undocumented residents are prohibited from enrolling in Medicaid or obtaining coverage through the beWellnm marketplace. This lack of access to coverage leads to high medical debt for these residents and increased uncompensated care expenditure for hospitals and providers.

Those who do not qualify for Medicaid due to their immigration status are eligible for Emergency Medicaid Services for Aliens (EMSA).39 EMSA provides coverage for emergency medical care, encompassing services such as labor and delivery. EMSA may not entirely cover emergency medical expenses, and many individuals depend on charity care from hospitals to avoid medical debt. NMMIP was originally created in the late 1980s to cover the “uninsurable” population.40 While the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has now made it possible for individuals who were previously uninsurable to obtain coverage, undocumented immigrants, excluded from the ACA’s options, are still able to seek coverage through NMMIP.

This form of coverage is notably expensive; accordingly, NMMIP offers a Low Income Premium Program (LIPP) program that provides a premium reduction of 25%, 50%, or 75% depending on the applicant’s annual income.

Given the existing landscape of health access and affordability in New Mexico, the state government and legislature have proposed several programs to address these issues. NAPA, CEP, and Medicaid Forward are in various stages of implementation and are discussed below as elements of New Mexico’s health policy landscape.

Under NAPA, indigenous people who are members of a federally recognized tribe are eligible for either a zero-premium plan on the marketplace (for those earning up to 300% FPL) or a reduced premium plan (for incomes between 300 and 400% FPL). As of 2023, 300% FPL is $40,770 for an individual, $54,930 for a couple, or $83,250 for a family of four.41 Concurrent with the introduction of NAPA, there has been a doubling of health insurance enrollment on the beWellnm marketplace, from 500 to 1,000. While this may not be fully attributable to NAPA, recent action does seem to be increasing indigenous enrollment.42 While the increase in uptake was a promising development, estimates show that 90% of indigenous New Mexicans eligible for premium assistance remain without coverage.43

Utilizing resources from the New Mexico Health Care Affordability Fund (HCAF), OSI has proposed establishing a collaborative initiative with NMMIP to introduce CEP. This plan aims to mitigate affordability and access challenges currently experienced by uninsured New Mexicans and low-income NMMIP enrollees without access to other coverage options. Under OSI’s proposal, individuals may qualify for CEP if they:

• Reside in the State of New Mexico and earn up to 200% FPL.

• Lack access to Medicaid, Medicare, beWellnm, or employer-sponsored insurance (ESI).

• Are either uninsured or enrolled in LIPP-75%.44

CEP will mirror the state’s Medicaid program and will encompass the ten essential health benefits, with HSD continuing to cover services eligible for federal matching dollars under Emergency Medicaid. Premiums and out-of-pocket costs will be income-dependent, with Plan A catering to individuals with incomes up to 138% FPL and will closely resemble beWellnm’s Turquoise 1 Plan (99.2% actuarial value) which includes a $0 deductible. Plan B covers those with incomes between 138-200% FPL, mirrors beWellnm’s Turquoise 2 Plan (95.1% actuarial value) and offers a $100 deductible.45

The ACA requires non-grandfathered health plans in the individual and small group markets to cover essential health benefits, which includes the following ten benefit categories: (1) ambulatory patient services; (2) emergency services; (3) hospitalization; (4) maternity and newborn care; (5) mental health and substance use disorder services including behavioral health treatment; (6) prescription drugs; (7) rehabilitative and habilitative services and devices; (8) laboratory services; (9) preventative and wellness services and chronic disease management; and (10) pediatric services, including oral and vision care.

Drawing from comparable programs in other states, data indicate that enrollment typically ranges from between 25-40% of eligible individuals. According to modeling commissioned by OSI, CEP could potentially attract between 6,250 and 12,000 new enrollees in the first year, assuming take-up rates fall within the 25-40% range.

New Mexico is considering expanding the availability of publicly-run coverage to more residents through Medicaid Forward. Medicaid Forward, a legislative proposal that is currently under study, would provide residents above the current cutoff of 138% FPL with the option to buy into the state’s existing Medicaid program. Residents earning above 150% FPL would likely pay modest premiums and other cost-sharing requirements. Washington, DC has implemented a similar program up to 210% FPL;46 New Mexico’s proposed program, on the other hand, may raise the limit to 400% FPL or more.47

The Urban Institute estimates that this program would reduce the uninsurance rate from 13.1% to approximately 5.75%.48 It has the potential to improve member experience by eliminating churn and providing New Mexicans with a stable, reliable source of coverage, regardless of income or employment status. Critically, it would also be available to all residents regardless of immigration status.

In early 2023, the legislature passed HB 400, which tasked the Secretary of Human Services with studying the impacts of Medicaid Forward.49 This study will suggest detailed implementation and operational plans, necessary provider reimbursement changes, funding sources, and coverage eligibility. These findings are due in October 2024 and will inform the future of Medicaid Forward.

The policies above are part of a complex existing policy landscape. While the policies below are not the focus of this report, they interact with the proposed solutions and are important to understand when analyzing how the proposed policies will impact health equity.

HCAF was created in 2021 to serve the needs of underinsured New Mexicans.50 This fund collects $165 million each year using a state version of a recently expired federal fee on insurers.51

Currently, HCAF has three components:52

1. NAPA guarantees the availability of $0 premium plans for up to 200% FPL and lowers premiums for those between 200-400% FPL.53 This is one of the policies examined in the report.

2. The Native American Affordability Fund completely buys down the premiums for those <300% FPL and reduces premiums for those within 300-400% FPL.

3. The State Out of Pocket Assistance Program makes utilizing coverage on Tur quoise Plans more affordable by reducing cost-sharing and improving behavior al health coverage.54, 55 Although these plans significantly reduce the amount of out-of-pocket costs, they do not necessarily ensure affordable coverage or elimi nate the possibility of medical debt.

HCAF builds on the premium subsidies and marketplace structure that the ACA created to establish more affordable coverage for low-income and indigenous groups.

Initially authorized in 2013,56 New Mexico’s marketplace, beWellnm, officially launched in 2021 for 2022 plan year enrollment, transitioning fully from the federal marketplace.57 BeWellnm is a source of affordable coverage for over 40,000 enrollees,58 most of whom do not receive ESI but are not eligible for Medicaid. Marketplace coverage is particularly important due to the comparatively low rate of ESI in New Mexico.

New Mexico’s Medicaid program, called Centennial Care or, as of 2024, Turquoise Care, is a pillar of health coverage in the state.59 New Mexico has the highest proportion of its population enrolled in Medicaid among all states60 and was among the first wave of states that expanded Medicaid in 2014.61 According to survey results from 2022, residents hold Centennial Care in high regard, with 67% saying it is a high-quality, trusted program.62 It is centrally administered by HSD, which contracts with four Managed Care Organizations (MCOs) to provide health benefits.63 The overwhelmingly positive perception of the state’s Medicaid program would provide a strong foundation for Medicaid Forward’s image, if the proposal were to proceed.

During the public health emergency (PHE) resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, a condition of receiving federal relief dollars was that states could not disenroll individuals from Medicaid except under very limited circumstances. The Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022 ended this continuous coverage requirement as of April 1, 2023 At that point, states began the process of “Medicaid unwinding,” or disenrolling people from the program who were no longer eligible.

Medicaid unwinding has been a challenging process across the country. Stakeholders in New Mexico mentioned staffing constraints in the Human Services Department (HSD), which is facing an estimated 40% vacancy rate, as a challenge to keeping up with the workload and avoiding procedural disenrollment.

Procedural disenrollment occurs when someone is removed from Medicaid for administrative reasons, such as outdated contact information or failing to respond to re-enrollment paperwork. Individuals who are procedurally disenrolled may still be eligible for the program.

Programmatic disenrollment occurs when someone is no longer eligible for Medicaid due to income or health status changes.

As of November 2023, 96% of people disenrolled from Medicaid in New Mexico had been removed for procedural reasons.64 Of the more than 60,000 disenrolled by July 2023,65 30,000 procedurally disenrolled people have re-enrolled in Medicaid coverage. People who no longer qualify for Medicaid should be shown a zero-dollar premium plan, for which the majority are eligible. Although beWellnm is notified when people are disenrolled from Medicaid in the unwinding process or otherwise, only a small portion sign up for marketplace coverage. Transitioning those disenrolled from Medicaid to marketplace plans is a problem nationwide, with states struggling to reach newly uninsured families about their options. Those who do not sign up for Medicaid or a marketplace plan frequently remain uninsured.

As of the writing of this report, New Mexico is currently seeking a five-year 1115 Medicaid waiver (under the name “Turquoise Care”) that would add several new programs, including continuous eligibility for children under six, expanded access to home-visiting and supportive housing, Medicaid for high-need (serious mental illness, substance use disorder, or intellectual disability) justice-involved people 30 days before release, traditional healing benefits for Native Americans, and home-delivered meals.66

The continuous eligibility provision means that no form of recertification would be required to children under six. As New Mexico has a particularly high procedural disenrollment rate from Medicaid, the continuous eligibility provision would prevent detrimental, early-life disruptions in coverage due to missing paperwork.67

In terms of traditional healing, Native Americans with Medicaid and a nursing facility level-of-care need may currently receive up to $2,000 of annual culturally-appropriate therapies, including dance, song, plant medicines, participation in sweat lodges, or other care provided by a community-recognized healer.68 The new waiver would provide $2,500 of traditional healing to all Native American Medicaid members.69

Through Section 1115 of the Social Security Act, the Secretary of Health and Human Services can approve budget-neutral demonstration programs to assess improved ways of serving Medicaid patients.70 Savings from one aspect of the demonstration can be used to fund another component.71

As discussed, a unique component of New Mexico’s care infrastructure is its highrisk pool, founded in 1987 to cover ‘uninsurable’ populations.72 Uninsurable people, historically, were those with preexisting conditions. Although individuals with preexisting conditions are now insurable thanks to the ACA, the high-risk pool is still used to cover undocumented immigrants, who are left out of the ACA’s options.

74

73 It is an expensive form of coverage and some of the policies discussed below cover similar populations to those currently on NMMIP plans with more affordable options.

IHS is another critical component of care in New Mexico. IHS provides care at its facilities75 but a Purchase/Referred Care agreement is necessary for those traveling or seeking specialized care that is unavailable at IHS facilities.76 This lack of comprehensive coverage can be a barrier for indigenous people in accessing care.77 The Tribal Budget Formulation Work Group estimates that IHS would need a 700% budget increase over its 2022 budget to provide perfectly comprehensive health care to indigenous people of New Mexico.78 The Urban Indian Health Centers, which are designed to care for indigenous New Mexicans in metropolitan areas outside of tribal land, are similarly chronically underfunded (1% of IHS funding goes to these centers).

Additionally, Forward Together found in a survey that over a third of indigenous New Mexicans are uncomfortable receiving care at an IHS facility, primarily due to challenges obtaining an appointment and poor quality of care.79 According to Dr. Lucero (Zia Pueblo Tribe), the high turnover rate at IHS facilities leads to additional issues as there is no consistency in providers over time. Accordingly, “The concern is more than just having a provider who knows you; it is also about having a provider who understands your community, culture and beliefs.”80 This high turnover rate also undermines efforts to train providers in even basic cultural competency, exacerbating challenges around building trust in the health care system.

Sample

Between September to November 2023, the authors of this report conducted 15 interviews. Two interviews were with government agencies from neighboring states that have experience with similar policies to those New Mexico is considering. The remaining 13 interviews were with representatives from government agencies, advocacy groups, providers, and carriers in New Mexico.

The faculty advisors, Heather Howard and Dan Meuse, conducted the initial outreach to all interviewees. The authors of the report met with each group for 30 to 60 minutes in-person or over Zoom. The authors informed all interviewees that the notetaking was for factual information, not for attribution. The authors went back and obtained permission for all attributions made throughout the report during the writing process.

In addition to insights from the interviews, the report also analyzed administrative data and incorporated a review of academic and professional literature.

Approach

This report examines the three programs requested by OSI (NAPA, CEP, and Medicaid Forward) and evaluates their potential for closing health disparities and achieving health equity in New Mexico. The report also examines the provider shortage issue in New Mexico and makes recommendations to increase provider availability. Each section of the report proceeds in the following manner:

• A problem statement that lays out the health equity issues that each proposal seeks to address;

• Background that provides additional context on issues facing the policy in New Mexico and programmatic details;

• Recommendations that identify the opportunities for each policy to maximize its impacts on achieving health equity; and,

• Considerations to keep in mind when implementing the policy as is or any recommendations proposed by the authors of this report.

Evaluative Criteria

For each of the three policies and the provider shortage issue, the authors sought to address the following questions that fit into two broad categories:

1. Health Equity

a. How does the program promote coverage access?

b. How does the program enhance affordability for its consumers?

c. How does the program address the provider shortage issue in New Mexico?

d. Is the community involved in the design of the program?

2. Implementation

a. What is the administrative burden on the state?

b. What is the financial impact of the program? Is it cost-effective?

c. What is the political feasibility of the program to receive continued funding or to become a reality?

d. How might the program be impacted by the dynamic federal environment? How reliant is it on federal funding sources and authorizations?

One limitation of this report is the lack of representation of indigenous communities in New Mexico among the interviewees. The faculty advisors contacted one Pueblo based on recommendations from New Mexico state officials, but were unsuccessful in setting up a meeting. The authors sincerely regret the lack of inclusion of the lived experiences of indigenous communities in New Mexico and take full responsibility. The authors’ failure to include indigenous voices in this report also speaks to the greater issue of need for trustbuilding with these communities given the history of the United States. Trust is a challenging word…because there has been such a long history of broken promises. - Tom Betlach, former Arizona Medicaid Director, when asked about how Arizona approaches conducting outreach to indigenous communities

The report therefore only is limited to discussions of the observable experience of indigenous communities interacting with the health care system in New Mexico and commentary from advocates working on issues related to indigenous experiences. Furthermore, this report focuses on the interactions on indigenous individuals with the health care system administered by the New Mexico state government, rather than a comprehensive overview of their interaction with IHS or tribal health providers and state-based health care. The report does not seek to present a whole picture but rather focuses its attention on aspects of health inequities that can be addressed from the lens of the three programs examined and the provider shortage issue.

““Trust is a challenging word... because there has been such a long history of broken promises.” — Tom Betlach81

Problem Statement

As of 2019, the indigenous peoples of New Mexico had the highest uninsurance rate of all racial and ethnic groups in the state. Of the 187,000 non-elderly uninsured residents, almost 20% are indigenous. Approximately 75% of uninsured indigenous people earn less than 400% FPL.82 NAPA aims to increase the affordability of health insurance to enrolled tribal members by offering zero-dollar premiums for marketplace plans to indigenous people earning under 300% FPL and reduced premiums for indigenous consumers between 300 to 400% FPL. BeWellnm estimates that the average monthly subsidy through NAPA is $14.92 per month.83

This section provides background information concerning the Native American health insurance and care landscape and discusses relevant policy considerations concerning the efficacy of NAPA in improving health equity.

Indigenous communities in New Mexico experience health disparities due to lack of access to providers, uninsurance and underinsurance, and a combination of poor outreach and historical injustice. Uptake of NAPA remains low, with our fieldwork suggesting that approximately 1,000 indigenous individuals (~0.05% of the entire indigenous population in New Mexico) are currently enrolled in a marketplace plan.84 Our research and fieldwork highlighted four drivers of limited NAPA uptake. First, NAPA does not improve physical access to providers, one of the major challenges facing indigenous people. Second, some individuals who are served by IHS believe that it provides more comprehensive coverage than it actually does.85 Given this, there is little demand for a marketplace plan on top of the coverage they believe IHS provides, thus contributing to low NAPA uptake. Third, nascent outreach around the NAPA program has had low efficacy so far, and has run into pervasive distrust of government-run programs in the target communities. Finally, NAPA alone does not completely solve the issue of affordability for all plans that an individual might choose, as it focuses on the issues of premiums, rather than large medical debt contributors, namely coinsurance and deductibles.

Lack of access to qualified providers is a pervasive problem in New Mexico, even if individuals are insured. The impacts are especially extreme for New Mexico’s indigenous populations, who frequently rely on the underfunded IHS system and live in rural or small towns with significant provider shortages (73% of indigenous New Mexicans live in rural or small towns).86 The NAPA program is intended to address the affordability of health insurance premiums; while it does not directly address this accessibility issue, expansion of insurance coverage is associated with better access to care. According to the 2017-2021 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey (BRFSSS), only 60% of indigenous New Mexicans had a primary care provider, as compared to 70% of all New Mexicans.87

The geographic accessibility challenges that make health care access difficult are exacerbated by chronic underfunding of IHS. Funding constraints mean IHS struggles to fund enough providers across specialties. The Tribal Budget Formulation Work Group estimates that IHS would need a 700% budget increase over its 2022 budget to provide perfectly comprehensive health care to indigenous people in New Mexico.89 This underfunding of IHS leads many indigenous people to postpone care for the next fiscal year, as they are unable to receive care at an IHS facility when IHS has exhausted its budget.90

In addition to the difficulties of simply accessing a primary care provider or relevant specialist, indigenous New Mexicans also face challenges in receiving care from a trustworthy and culturally competent provider. There are only 3,400 indigenous doctors in the entire United States, and only 3% of New Mexico’s mental health providers are indigenous.91 The lack of cultural competence among non-indigenous providers can lead to negligence and harm, including the

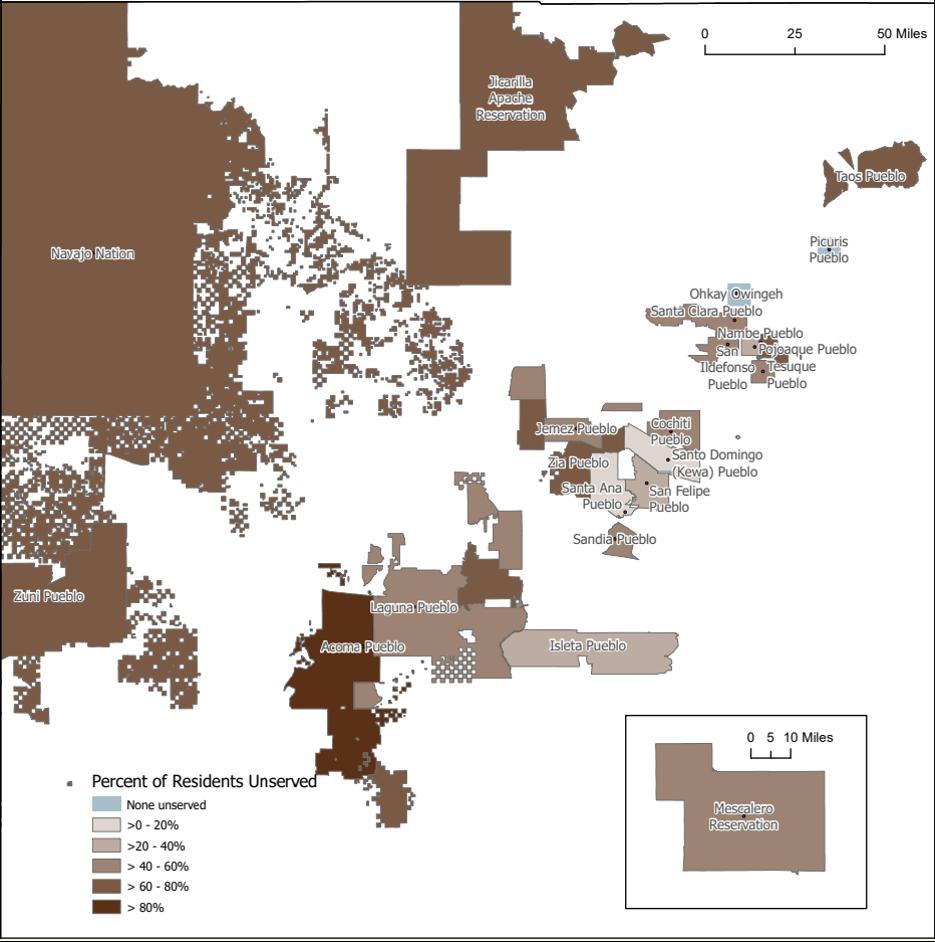

Source: NM RGIS, U.S. Bureau

A network analysis conducted in ArcGIS Pro created a 30-minute driving distance service area of medical facilities, FQHCs, and IHS available from RGIS NM. Using the area of land covered and applying the percentage to the population in each tribal land or pueblo, an estimate of individuals living in an area outside of the service area is calculated. Because population density is not taken into consideration, the estimates here are merely suggestive.

2023 death of a Navajo speaker in New Mexico who was not provided an interpreter and whose altered mental state was thus missed by hospital staff.92

Due to these access issues, indigenous New Mexicans have worse outcomes on a number of preventable health indicators, including a 2.6 times higher age-adjusted mortality rate from diabetes and a 3.3 times higher age-adjusted alcohol-related mortality rate.93 While diabetes and alcohol abuse disorder are related to many other facets of colonization, including poverty and loss of traditional lifeways, the high mortality rate implies a failure of health care. In 2020, these inequities meant an indigenous person born in New Mexico could expect to live ten fewer years than the average New Mexican.94

During the COVID-19 pandemic, indigenous communities in New Mexico were particularly hard-hit, with the Navajo Attorney General Doreen N. McPaul stating that “We’ve had some really sad situations where COVID-19 has wiped out almost an entire family.”95 A University of New Mexico Hospital study found that their indigenous patients were more than three times as likely to be severely ill and more than twice as likely to die.96 The study also found that these patients had fewer preexisting conditions than other racial or ethnic groups, and were significantly younger. The authors of the study suggested that a lack of early intervention could be a contributing factor, again highlighting the lethal toll of inadequate health care access.97

In New Mexico, 16.2% of indigenous people are uninsured.98 While IHS provides health care to many indigenous people, the dramatic underfunding of IHS leads to insufficient health care provision for uninsured individuals. IHS primarily provides preventative care (“direct care” at IHS or tribal facilities) and refers people to specialist care through the “Purchased/ Referred Care” (PRC) program, if their tribe has bought into the PRC program.99 For example, the IHS Santa Ana Health Center only provides care for general medicine, diabetes, pediatrics, women’s health, and audiology.100 The diabetes and women’s health clinics take place once per month, and general medicine is provided 2.5 days of the week. For any other kind of care, or more frequent access to care, an individual may need to visit a non-IHS facility. According to Dr. Lucero, underfunding of IHS has led to essentially rationed care, with IHS only willing to pay for “Priority One” (immediate loss of life or limb) PRC reimbursements towards the end of the fiscal year.101 This results in uninsured patients either going without care until their condition becomes life-threatening, or paying out of pocket.

The burden for paying for care outside of IHS facilities frequently falls upon the uninsured individual, according to the IHS website, as all referrals are subject to final determination by IHS before payment.102 In sum, indigenous people are often stuck with the bill if IHS denies the claim or exceeds funding. Due to this high uninsurance rate and lack of adequate IHS funding, the New York Times found that between 2016-2019, indigenous people accumulated over $2 billion in medical debt.103

Since the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid, New Mexico has made significant strides in better insuring indigenous people through Medicaid. Medicaid recipients do not pay a premium, deductible, or coinsurance, and thus face significantly lower cost barriers than uninsured people.104 In addition, Medicaid reimbursement of IHS and tribal providers can provide spillover benefits to indigenous communities and nations by freeing up additional budget space. In 2013, 36.5% of nonelderly indigenous New Mexicans were covered by Medicaid, as compared to 60.2% in 2022.105 Despite this progress, over half (57.8%) of uninsured indigenous people in New Mexico are eligible for Medicaid and not enrolled, suggesting that there are thousands of people who are currently forgoing care or paying out of pocket for care that could otherwise be covered by Medicaid.106

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Our interviews with key stakeholders and review of the data indicate that beWellnm has a far lower uptake than Medicaid in indigenous communities. In 2019, 37.3% of indigenous people who were eligible for marketplace insurance were uninsured, while the uninsurance rate was half of that (13.2%) for people eligible for Medicaid.107 This highlights the need for more outreach to focus on marketplace options and accessibility. In total, around 11,000 nonMedicaid-eligible indigenous New Mexicans could receive some kind of premium assistance through NAPA. BeWellnm estimated in our conversation that they are currently serving 1,000 indigenous people.108 Thus, we estimate that they are currently serving less than 10% of the eligible indigenous population. Given the relative nascency of the benefit, we expect that beWellnm should be able to continue expanding access to NAPA in the upcoming years.

A major component of uptake when introducing an assistance program is ensuring that the target audience knows the program exists and that it is meant for them. Successful outreach around NAPA must both be extensive and effective, reaching rural communities and clearly communicating the need the program addresses, to promote uptake. Three key barriers to effective outreach emerged from our meetings with stakeholders: language barriers, methods used to reach populations, and a lack of trust.

1. No matter how well-constructed a health care platform, navigating a complicated system full of terminology and nuanced choices is challenging.109 These challenges are exacerbated for indigenous populations because of language barriers, including a lack of support in their native languages.

2. Our conversations also indicated that outreach methods in general were limited. In multiple conversations, online resources and mailing efforts were highlighted as the primary outreach strategies. Many indigenous populations do not have consistent access to broadband which reduces the applicability of online resources. Additionally, lower-income populations tend to move addresses more frequently, making it harder for mailed resources to reach their intended recipient. BeWellnm is making new efforts to increase community engagement, including texting and calling, as well as facilitating outreach through trusted members of communities.110 As these efforts are recent, the outcomes of these strategies are still unknown. However, according to our fieldwork, beWellnm reported that in a recent survey prior to their new outreach efforts, the majority of New Mexicans surveyed were unaware of beWellnm or its outreach efforts. BeWellnm attributes much of this visibility issue to the organization’s previous lack of a year-round community presence.

3. Lastly, there is a pervasive and well-justified distrust of government-run programs among indigenous populations. A history of federally run medical and scientific studies that were conducted in unethical ways on indigenous populations have created a significant culture of mistrust and skepticism that the New Mexican government must now overcome.111 Further negative experiences of indigenous individuals in Western doctor’s offices, from sterilization to discrimination, have also rightfully increased mistrust.112

Out-of-pocket costs may remain high for plans on the marketplace, even with NAPA subsidies that fund zero-dollar or reduced premiums. While NAPA can make higher quality (lower outof-pocket, likely gold or platinum) plans more affordable on a monthly basis, NAPA reduces premiums for any plan that someone selects. The premium assistance provided by NAPA could allow someone to buy a “better” plan that has lower out-of-pocket costs, but out-ofpocket cost-reduction is not a direct benefit of NAPA. An individual would need to have a

thorough understanding of health insurance terms (i.e., what “deductible” means) in order to use the NAPA program to select a plan that actually guarantees affordable care. Thus, without familiarity with health insurance terms or adequate navigation guidance, a chronically ill person may select a plan with high costs that does not effectively reduce the out-of-pocket costs of their continuing care needs. Ideally, beWellnm should consider guiding all NAPA recipients to use their premium assistance to purchase a gold or platinum plan with zero or very low deductibles and no coinsurance.

Given the complexity of choosing a marketplace plan, beWellnm has an opportunity to assist indigenous consumers to use NAPA assistance most effectively. Currently, different marketing materials state both that there is a “zero cost-sharing” plan available to indigenous communities and that plans “can reduce your premiums, copays or deductibles to zero” (emphasis added).113, 114 If indigenous consumers believe that NAPA alone will fully reduce their out-of-pocket burden, they may be less careful to pick a plan that minimizes coinsurance, copays, and deductibles. Marketing materials also state that with marketplace plans, indigenous consumers do not need to pay copays, deductibles, coinsurance at IHS, despite the fact that indigenous people never need to pay these out-of-pocket fees at IHS facilities, regardless of insurance status. BeWellnm should consider unifying the messages about NAPA to best support indigenous communities’ trust and understanding of the marketplace.

We continue our discussion with policy recommendations and limitations for OSI to consider as they continue their work on health equity in New Mexico, and specifically, to increase the uptake and efficacy of NAPA. We note that the following policy considerations may have transferability beyond the NAPA program.

First, we recommend that OSI undertake and support other entities in pursuing a more comprehensive approach to culturally competent outreach in indigenous communities. Personal relationships and trust between insurance providers and Native Americans are important parts of this outreach. We suggest building an outreach strategy that funds deputized members of indigenous communities as outreach agents, utilizes existing relationships between community programs and indigenous communities, and prioritizes relationshipbuilding with tribes.

As part of our research, we spoke to states neighboring New Mexico, including Arizona, that have seen higher rates of health insurance uptake by indigenous people. We sought advice and insight into building trust and open communication channels between indigenous populations and the government. We also studied other states across the United States that have more robust relationships between indigenous peoples and the federal, state and local governments, like Washington and Alaska. Our goal was to understand what has been done differently, and what may be applicable to New Mexico.

1. Use community programs that already have existing relationships with tribes. This allows work to progress rapidly, instead of spending time building new relationships and trust before working on health insurance uptake. Existing relationships and familiar community programs will also add legitimacy to outreach efforts, as it is not the federal government coming in alone, but rather actors who know and care for the indigenous communities, introducing opportunities for better health care.

2. Collaborate with tribal leaders, enabling them to be direct spokespeople for their tribes. In a similar vein, this strategy recognizes the importance of trust and strong relationships in generating uptake. According to Kenneth Lucero, a Pueblo scholar,

“tribal leadership is responsible for looking after the community as his children.”115 Native American communities are more likely to trust that NAPA and other health insurance programs can improve their quality of life if the messaging comes from a familiar and trusted leader, as opposed to a stranger who has not invested in their community before. This also reduces the lift of program administrators to educate one or a few leaders, as opposed to trying to reach an entire population.

3. Come to the tribes on their terms. In practice, this looks like prioritizing traveling out to the tribes, as opposed to having them travel to Santa Fe. Currently the Native American Technical Advisory Committee (NATAC), which is composed of representatives from the Tribes, Pueblos and Nations, has the opportunity to meet in-person with HSD’s Medical Assistance Division Director on a quarterly basis to discuss health care. These meetings, however, are conducted on-site at the department, and in a Western framework.116 Former Arizona Medicaid Director Tom Betlach recommended that senior staff both be educated by trial liaisons around the history of broken promises to tribes and that senior staff travel in person to respectfully listen to tribal leaders speak about their priorities. In his words, “presence matters,” and it is fully worth driving multiple hours so that senior staff can hear from indigenous people directly.117 Meeting the tribes on their terms also means spending time understanding needs from their point of view and considering policy adaptations based on their feedback. Currently, few sovereign tribal nations provide notable input into their own health care policy.118 By including indigenous voices in the development of assistance programs, rather than keeping them only on the receiving end of the programs, we can create policies that better reflect community needs. Betlach recommended that instead of entering conversations with the aim of “problem solving,” the true job of state officials is to listen respectfully to tribal representatives speaking and to then shape policies around this feedback.119

4. Improve coordination between state and health entities who work with New Mexico’s indigenous peoples. Throughout stakeholder conversations, we found that there is little coordination between different entities working with New Mexico’s tribes. Outreach coordination between entities like OSI, beWellnm and the Office of the Tribal Liaison within the NM Department of Health could allow entities to build on existing relationships and see outreach improvements on a shorter timeline than if they worked alone.

Over time, OSI and other administrators of health insurance programs should strive to strengthen direct relationships with tribes, resulting in a comprehensive understanding of needs and tools to address those needs.

Outreach efforts need to address:

1. How IHS interacts with health insurance coverage, and what services insurance coverage provides that IHS does not: Although beWellnm provides a pamphlet outlining the differences, these resources need to be supplemented with effective and thoughtful outreach to their intended populations.120 Another possible challenge here is that even when made aware of the gaps in IHS care, indigenous populations may not see a need for greater coverage.

2. The specific help NAPA provides: If the benefits of NAPA are misrepresented or misunderstood, this runs the danger of increasing distrust in US government-run “aid” programs. Specifically, outreach should outline what insurance covers and what obligations remain with the covered individual.

3. The status of access to culturally competent care and traditional healing through

insurance coverage vs IHS coverage: As a baseline, “many AI/AN believe that their health care providers need to know about the history and culture of their tribe before they can accept them and respect them as individuals.”121 Additionally, there is a demand for traditional healing as well as Western medicine.122 For individuals who prefer or seek out traditional care, there is little motivation to buy Western health insurance. Thus, communication also needs to focus on the value of access to Western medicine if and when a person may need it, as well as ongoing work to pay for traditional healing through Medicaid.

In order to build trust with indigenous communities, it is crucial that NAPA has consistent and sufficient funding. As Dr. Heather Sauyaq Jean Gordon (Iñupiaq, Nome Eskimo Community), Dr. Deana Around Him (Cherokee Nation), and Elizabeth Jordan write, the “chronic underfunding” of IHS and resource inadequacy of other health programs undermine trust and indigenous self-determination.123 Given historical relationships with indigenous communities, it will take time to build authentic relationships. Similarly, global health decolonization efforts emphasize that “in contexts of exclusion and marginalization,” policy change “requires time and sustained support that allows for the reconfiguration of societal-level power dynamics.”124

Rather than cutting back NAPA due to current poor uptake, we advocate for increased funding. New Mexico should consider the following:

1. Fully address affordability concerns As discussed in the Affordability section, NAPA does not address deductibles, coinsurance, or copays. NAPA could be expanded to cover these out-of-pocket costs for any plan that an indigenous person may choose to buy.

2. Increase navigation resources. New Mexico should consider hiring several more year-round indigenous community health workers (CHWs) who can assist individuals in enrolling in insurance. As an example, Diné College and Northern Arizona University worked together to train 35 Diné College students to provide vaccine safety education – a similar approach could be taken with insurance enrollment.125

3. Provide financial resources directly to tribes. As seen with the COVID-19 pandemic, supporting tribal sovereignty and providing resources directly to tribes is an effective way to enhance public health.126 For example, the Navajo Nation used a culturally relevant communication approach (responsibility to elders and ancestors), intense health messaging (including in the Navajo language), trust building through role models and participation in the vaccine trials, and a doorto-door mobile vaccination campaign.127 A similar approach could be taken with insurance enrollment, if sufficient funding was provided to tribal entities.

4. Ensure that there is continuity of funding. In order to increase people’s awareness and use of NAPA, NAPA must remain a reliable, adequately funded program.

5. Consider a continuous enrollment process and improve communication between Medicaid and beWellnm. Currently, individuals must re-enroll and re-select a health plan on the marketplace every year. If a person’s income has slightly changed, this also leads to benefit cliffs. For example, if a person is now at 139% FPL instead of 138%, they will need to shift over to the marketplace instead of Medicaid. Re-enrollments and changing between insurance providers causes attrition, as currently seen with Medicaid Unwinding. We advise that New Mexico consider a continuous enrollment process and develop infrastructure to warmly hand off people between programs. Rather than spending on funds on renewal and recertification, it may be more cost effective to ensure that people maintain insurance. Medicaid Forward may be one way to create more continuous coverage.

Meaningfully addressing health inequities will require the commitment of substantial funds to NAPA. We advise that the state meet with tribal representatives, indigenous-led community organizations, and indigenous health experts to hear feedback on NAPA. If there is consensus that NAPA has the potential to be a meaningful program in addressing health inequities, we advise that New Mexico take steps to ensure that NAPA has sustainable funding for complete enrollment going forward. This approach would be distinct from making the program available to a limited number of individuals based on the variable amount of revenue generated by the insurance surtax. If outreach is successful, the state must be prepared for exponential growth in enrollment. Similarly, we recommend that New Mexico consider the political climate across levels of government around programs aimed only at indigenous people. New Mexico should take steps to advance long term funding continuity of the program, so as to be able to ensure that program provision does not fluctuate with external political changes.

““Meaningfully addressing health inequities will require the commitment of substantial funds to NAPA.”

A major recurring theme in all New Mexico health equity conversations is the provider shortage. No matter which way the issue is sliced, the bottom line is clear: New Mexico needs more providers. In the specific context of NAPA, and improving indigenous health outcomes and access in general, we reduce the scope of the problem to the following: New Mexico needs more indigenous providers, as well as providers educated in indigenous cultural competency. While cultural competency training is a step in the right direction, having indigenous care providers supporting indigenous communities is even better. We highlight a few of suggestions below to this end:

1. Establish middle school or high school programs that get local students interested in health care from a young age. Early exposure to potential career paths, especially ones that can be brought back to a community could lead to more indigenous youth moving into the health care sector.

2. Develop financial support structures for providers who do want to return to their communities as health care workers. Currently, providing health care in rural areas is prohibitively expensive for an individual provider. Thus, even if a trained provider has the desire to return and open a practice in their community, it is economically infeasible. Financial programs to support such providers could pay dividends to the state of New Mexico for years to come in the form of improved health outcomes throughout the state.

3. Expand CHW programs targeting participation from indigenous communities, and develop a community health worker to more accredited provider pipeline. CHW training and accreditation is a relatively quick process, but can simultaneously help address provider shortages and start indigenous people on the path to becoming a more accredited health care provider.

Problem Statement

New Mexico faces a pressing challenge in ensuring equitable health care access for uninsured individuals without access to common forms of coverage (such as Medicaid and the beWellnm marketplace). These individuals, some of whom are undocumented, constitute a significant portion of the state’s diverse communities and contribute meaningfully to the state’s economy and cultural vibrancy. However, disparities in health care access persist, creating a critical need for targeted policy interventions.

Access issues arise from the complex interplay of federal regulations, which impose significant barriers to health care access for uninsured, undocumented individuals. Legal restrictions, compounded by fear and uncertainty stemming from evolving federal policies, create a chilling effect within the undocumented community, hindering their ability and willingness to seek essential health care services. The existing health care landscape further exacerbates the problem, as uninsured individuals are currently ineligible for federal public benefits, including Medicaid. Despite the state’s efforts to bridge the coverage gap through proposed initiatives like CEP, challenges persist in determining eligibility criteria, ensuring effective outreach, and addressing language barriers that impede access to vital health care information. Additionally, potential volatility in funding, specifically the surtax used for HCAF, raises concerns about the sustainability of programs like CEP in the long term. Without secure and permanent funding, the state risks compromising the continuity of essential health care coverage for vulnerable populations.

In summary, the problem at hand encompasses multifaceted legal, policy, and systemic barriers that hinder uninsured individuals without access to Medicaid and marketplace coverage from accessing critical health care services. Addressing this issue requires a comprehensive and sustained effort, involving policy adjustments, community engagement, and the establishment of secure and permanent funding mechanisms to ensure the enduring success of health care initiatives like CEP.

New Mexico has a strong immigrant community; almost one in ten residents were born abroad, and one in nine residents are native-born U.S. citizens with at least one immigrant parent.128 As of 2018, the state was home to 198,522 immigrants, comprising 9% of the population. These individuals hail primarily from Mexico (72%), followed by the Philippines, India, Germany, and Cuba. These immigrants actively contribute to various industries and enrich New Mexico’s diverse communities as neighbors, business owners, taxpayers, and workers.

Approximately 60,000 undocumented immigrants lived in the state as of 2016, constituting 29% of the state’s immigrant population and 3% of the state’s total population. Additionally, around 5,690 active DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) recipients have resided in New Mexico as of March 2020.129 Mixed status households are also prevalent in New Mexico; 35% (21,000) of undocumented residents currently live with a U.S. born child under the age of 18, and 17% (11,000) are married to a U.S. born spouse.

Immigrants play a vital role in the state’s economy, contributing hundreds of millions of dollars in taxes and adding billions of dollars to consumer spending. Nearly 19,000 immigrant entrepreneurs in New Mexico generate substantial business revenue ($319.5 million).130 Overall, immigrants are integral contributors to the state’s economic, social, and cultural fabric.

In our discussion of health care access for undocumented residents, it is crucial to differentiate between undocumented and lawful residents. Although both groups are immigrants and foreign-born, their levels of health care access differ significantly, especially in regard to Medicaid eligibility.

An undocumented resident, also commonly referred to as an undocumented immigrant, is an individual who resides in a country without the legal authorization to do so. This lack of legal status typically means that they entered the country without proper documentation or that their legal status has expired. Undocumented residents face challenges accessing certain benefits and their presence in the country is not officially recognized by immigration authorities. Undocumented residents still typically pay taxes and contribute to the local economy.

A lawful resident has legal authorization to reside in a country. In the U.S. context, this often refers to someone with a legal immigration status, such as a green card holder (lawful permanent resident) or someone with another type of authorized visa. Lawful residents have undergone a legal process to enter or remain in the country and are granted specific rights and privileges, such as the ability to work and access certain public services. Lawful residents are recognized by immigration authorities, and their presence in the country is in accordance with the laws and regulations governing immigration.

For the purposes of this report, we choose to focus exclusively on undocumented residents as they face the highest barriers to health care access and affordability.

Undocumented residents in New Mexico encounter distinct challenges in accessing health care. Even if these residents meet the state’s income eligibility criteria, they remain ineligible for Medicaid, based on federal law. Medicaid mandates that recipients must be lawful residents of the state where they receive health care. This generally restricts access to U.S. citizens and certain qualified non-citizens, such as lawful permanent residents outside of the five-year bar.131