5 minute read

Pathway to Spins

Text and diagrams by Christie Allan-Piper

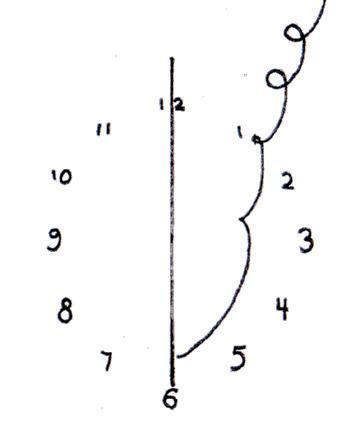

Nature repeats a good design. The Fibonacci or diminishing curve is found everywhere, in spiral galaxies, hurricanes, sea shells, pine cone—and the entrance into skating spins, two foot, one foot, forward and back (camel and flying spins excepted).

The figure skate is a precision instrument that carves its way to a circle’s center. There the skater circles, as if tethered to an invisible pole anchored to the center of the earth, rising to the sky.

The ice marks tell the tale. A spin entrance, like the curve into a school figure loop, is proportional to the skater’s height. For both loop and spin, the curve is key. After passing the long axis, the curve becomes so tight, the body must either resist the center’s pull, looping around it, or allow the skate’s forward motion to be arrested and spun. As the skate turns, the free leg releases, swings round and the spin begins.

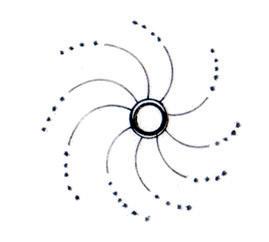

A great spin leaves the mark of concentric circles no larger than a dinner plate. Spins traveling slightly, not along on a line, but a platter, merely require adjustment. Some sagging body part, elbow, hip, or shoulder needs alignment.

A chain of small loops veering off a previously centered spin is evidence of the helicopter or tornado effect, lifting the mass off its moorings. Usually this pull can be resisted by pressing down shoulders, arms, free leg, and—importantly—the free foot heel, keeping the spin secure and fast.

A straight line of never centered loops indicates a three and spin begun too soon, before the skater passed the long axis and approached the center, in fact missing it altogether. The premature spin careened outward, away from the pole. Impatience and frisky free foot are culprits here. Telltale marks bespeak of a spin so wrong, it should have been stopped. A runaway spin is a danger to the spinner and all nearby. A skater must be taught to correct or abort at once. Shame on any coach who allows such a spin to be practiced!

For the forward spin, the free leg must be held back, behind the heel of the skating foot, until the curve is so small, the blade turns involuntarily. Then the free leg releases with force to make its own circular path around the center.

For the back spin entered by a forward inside edge, the free leg must be held in place, somewhat back, but inside the circle rather than behind the heel of the skating foot. In due course, the body rotates to face the foot, turns the three and spins.

Forward spin or back, the Fibonacci curve is the same, never cut short, free leg restrained, until it no longer can be. At the turn, the free foot releases to swing with a force of a circular sling shot.

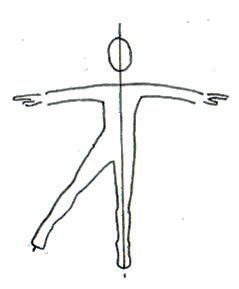

For the upright forward spin, hands and elbows are best held shoulder level, curved slightly forward, as if hugging a gradually shrinking tree. The great spin master, Gus Lussi kept forearms horizontal as they tighten and draw back close to the ribs. Like plane wings and sailboat booms, their horizontal force balances the vertical mass. (Strong skaters can manage vertical forearms, but weak skaters wobble.) Finally the arms, free leg and heel press downward against the body in a burst of speed.

The back spin begins with free arm strongly forward, skating arm strongly back and low, ready to punch up and inward, a swift upper cut as the spin begins. Again drawing in, forearms are most effective kept horizontal, hands flat, one above the other, thumbs hooked, elbows pressed against ribs, until straightening and pressing down flat against the body.

In change foot spins, each outward cut of the departing foot makes another Fibonacci curve. The mark of a well centered spin, with many changes of feet, resembles a pinwheel or spiral galaxy. When changing feet, one places the new foot on the rim of the wheel opposite the departing foot, one foot leaving as the other foot arrives.

Coming and going, feet must be parallel and apart. Skaters with open (spread eagle) hips must concentrate on turning the free foot inward. In transition, a turned out foot is as much impedance to a spin as an open door on a moving car. Toed in, blade parallel to the ice, the free leg offers least resistance to the air. Molding extremities to the line of flight, in this case circular, maximizes aerodynamics.

The spin is important for its own beauty and for the foundation and daily warm-up it offers jumps. Once spins are centered, the body is ready for airborne spins. But spins offer even more. In a chaotic world, the Euclidian design and logic of spins is reassuringly certain.

As in the eye of a storm, in a spin’s center, is stillness. Within an invisible, circular chamber, one feels the pull of centrifugal and centripetal forces in concert. Tethered to the invisible pole, one becomes a conduit between earth and sky, balanced amid the forces of the universe.

A spin can be read, understood, mastered. Centering spins, we learn to balance ourselves. Centering carries over to jumps and life, itself. The world may spin around us, out of control, but in it we can—must— hfind our balance and hold it strongly.

For more than fifty years now, I have done spins almost daily. Each one has been a meditation, exploration, revelation—a serene and hallowed moment.

Reprinted from Nov/Dec 2011 PS Magazine