ou have so many autumns: so many selves, waiting to be shake

down.”

ZHOU MENGDIE

$30 95 AVAILABLE IN THE PSA ONLINE STORE

Member Rate

ou have so many autumns: so many selves, waiting to be shake

down.”

ZHOU MENGDIE

$30 95 AVAILABLE IN THE PSA ONLINE STORE

Member Rate

As skaters progress through stages of lessons, they require more support and more aggressive blades. Jackson Ultima is the ONLY skate manufacturer that provides an extensive range of complete skates, which line up with the appropriate level of Learn to Skate.

PSA OFFICERS President

First Vice President

Second Vice President

Third Vice President Treasurer

Past President

PSA BOARD OF GOVERNORS West Mid-West East

Members at Large

Ratings Chair

Education Chair

Events Chair

ISI Rep to PSA

U.S. Figure Skating Rep to PSA

PSA Rep to U.S. Figure Skating Summit Chair

Diversity, Equity, &Inclusion

Executive Director

COMMITTEE CHAIRS Awards

Coaches Hall of Fame

Accelerated Coaching Partnerships

Area Representatives Hockey Skating

Sport Science Endorsements

Executive

Executive Nominating Finance

Nominating

Professional Standards PSA Rep to ISI

Adaptive Skating

PSA AREA REPRESENTATIVES

Area 1 Tracey Seliga-O'Brien

Area 2 Kimberlie Wheeland

Area 3 Andrea Kunz-Williamson

Area 4 Jill Stewart

Area 5 Angela Roesch-Davis

Area 6 Maude White

Area 7 Nicole Gaboury

Area 8 Jackie Timm

Area 9 Mary Anne Williamson

Editor Jimmie Santee

Art Director Amanda Taylor

Rebecca Stump

Tim Covington

Patrick O'Neil

Kirsten Miller-Zisholz

Lisa Hernand

Alex Chang

Russ Scott

Phillip DiGuglielmo

Andrea Kunz-Williamson

Ashley Wyatt

Cheryl Faust

Jill Stewart

Denise Viera

Denise Williamson

Peter Cain

Cheryl Faust

Denise Williamson

Danny Tate

Jane Schaber

Heather Paige

Kelley Morris Adair

Teri Klindworth Hooper

Darlene Lewis

Jimmie Santee

Andrea Kunz-Williamson

Alex Chang

Debbie Jones

Gloria Leous

Dianah Klatt

Garrett Lucash

Jimmie Santee

Alex Chang

Alex Chang

Lisa Hernand

Alex Chang

Kelley Morris Adair

Gerry Lane

Mary Johanson

Area 10 Francesca Supple

Area 11 Charmin Savoy

Area 12 Roxanne Tyler

Area 13 Liz Egetoe

Area 14 Marylill Elbe

Area 15 Tiffany McNeil

Area 16 Russ Scott

Area 17 Martha Harding

DISCLAIMER: Written by Guest Contributor | PSA regularly receives articles from guest contributors. The opinions and views expressed by these contributors are not necessarily those of PSA. By publishing these articles, PSA does not make any endorsements or statements of support of the author or their contribution, either explicit or implicit.

THE PROFESSIONAL SKATER Magazine Mission: To bring to our readers the best information from the most knowledgeable sources. To select and generate the information free from the influence of bias. And to provide needed information quickly, accurately and efficiently.

The views expressed in THE PROFESSIONAL SKATER Magazine and products are not necessarily those of the Professional Skaters Association.

The Professional Skater (USPS 574770) Issue 2, a newsletter of the Professional Skaters Association, Inc., is published bimonthly, six times a year, as the official publication of the PSA, 3006 Allegro Park Lane SW, Rochester, MN 55902. Tel 507.281.5122, Email: office@skatepsa.com

© 2023 by Professional Skaters Association, all rights reserved. Subscription price is $19.95 per year, Canadian $29.00 and foreign $45.00/year, U.S. Funds.

pushing the limits of human potential, and creating jaw-dropping moments.

Comparatively, Ice Capades did not adapt well to the changing landscape. Founded in 1940, Ice Capades was a fixture in arena’s across North America for 60 years though it became burdened by the audience's finicky needs and by the early 1990’s, the tour was bleeding cash. The owners filed for bankruptcy and Dorthy Hamil bought the show at a liquidation sale. After borrowing millions, the show still could not make it and was sold to Pat Robertson, the 700 Club evangelist. This version of Ice Capades toured for a season before selling again. While several attempts were made to bring the show back, none materialized.

Feld Entertainment was not the only business in the skating industry to employ this strategy. When reviewing the last five years of U.S. Figure Skating governance, it is apparent that creative destruction became their strategic objective. Whether it was a conscientious decision or not can be debated but the net results appear to be the same.

Let’s look at some of those changes. Starting from the ground up, U.S. Figure Skating first tackled a complete overhaul of what was their Basic Skills program. Rebranded to Learn to Skate USA, the program was updated and made leaner. Technology was further embraced with the launch of the Learn to Skate USA app and website. These changes provided a valuable boost to participating club and rink programs who were given products that individually would have cost them thousands of dollars. The marketing tools were slick. Another considerable change was the dismantling of the nine regional championships and reorganization of the entire qualifying competition structure. Gone were the Junior Championships and the Novice division in the U.S. Figure Skating Championships. With the introduction of the National Qualifying Series, it gave the best skaters in the nation multiple opportunities to advance. While it has increased the percentage that the best skaters would go through, it further divided the “haves'' and “have nots.” In order to counter that change,

the Excel program was introduced which has been a success from the beginning.

There is what I believe to be a minority group that has fought these changes over the years with the hope of holding onto the past. While our traditions are important, staying relevant in the current economic era necessitates aggressive innovation. Though the results of the aforementioned transformations will not be realized for some time, let's hope the decision makers are dedicated to the new direction. And if the strategic objectives fail, let’s also hope that our leaders have the courage to execute a new round of creative destruction.

Jimmie Santee EDITORAshley Brancaleone

Rosie Canter

Jennifer Demarco Buchholz

Sheena Fernandez

Scarlett Gibbs

Hannah Bay SG

Kelly Belin SPD

Aimee Buchanan SFS

Carla Cavazos RSS

Amy Dultz RFS

Candace Elmquist RSS

Katherine Erickson MG

Michael Farrell RSS

Thobie Fauver CFS

Brenna Greco MG

AnnaLi Harp SG

Alexander Ho SD

Tammy Jimenez SPD

Anna Kaverzina-Eppers SFS

Hockey Skating 1

Laura Baker

Katherine Haines

Summer LeBel

Hockey Skating 2

Ann Baharie

Laura Baker

Katherine Haines

Hockey Skating 3

Jane Hottinger

Ashley Kawalec

Lisa Olson

Maddi Spletter

Kelsey White

Ice Den Chandler Chandler AZ

Ice Den Scottsdale Scottsdale AZ

World Arena Ice Hall

Gloria Leous MFS

Bonnie Lewis RFS

Leine Newby-Esteralla SPD

Camila Antillon Novelo RFS

Gianna Scalisi SG

Alexis Slack CSS

Charis Sloan SSS

Jane Taylor CG

Kathryn Vaughn RSPD

Brittany Vise RFS

Kimberly Wilczak CSS

Ashley Wyatt RPD

Heather Young RG

Master Rating Achieved

Colorado Springs CO

Martha's Vineyard Vineyard Haven MA

Coach Aimee Skating Academy Lake Hiwwatha NJ

ONYX Suburban Skating Academy Rochester MI

Palm Beach Skate Zone Lake Worth FL

Palm Beach Ice Works West Palm Beach FL

Lauren Lumpkin

Allye Ritt

Ali Wegrzyn

Register now and be recognized as a progressive training facility dedicated to excellence in coaching both on and off-ice.

www.skatepsa.com

Lauren Lumpkin

Kaylee Pierce

Ali Wegrzyn

Charis Sloan Mentor ~ Denise Williamson

Ann Baharie Lauren Lumpkin

Hockey Skating 4

Lisa Goodman Nivole Hoisington

• Crystal Rose Sanders Level 1 Showcase

Kimberly Wilczak

Mentors ~ Svetlana Khodorkovsky & Mary Anne Williamson

Congratulations to our coaches for your determination and drive!

It happens to many of us, you bump into someone in line to get coffee and begin some small talk. You explain you are in town for a figure skating competition and they exclaim “Oh, I love figure skating! They move so gracefully on the ice…” and then they ask you about the Olympics. Yes, they nearly always ask. It does seem that there are many fans of our sport. Enthusiasts are enamored by various aspects of the figure skating: the dynamic jumps, fast and creative spins, complicated lifts, intricate coordination of steps, extended skating edges, and the list goes on. All of these talents require movement and investment to hone the actions into precise techniques that will prove consistently reliable in the delivery of elements and skills. The refinement of position to make it “easy on the eyes” requires attention to detail from a devoted coach and athlete willing to put in the time until developed and consistent. Movements are taught but often appear to lack an indication intent that the movement shows control, purpose, and attractiveness.

I am an ISU Singles Technical Specialist and serve on panels of all skating levels domestically and internationally and have noticed a popular trend in the singles discipline to include the sliding movement. Many skating programs have some kind of sliding movement incorporated into the choreography within the body of the program or the ending of the program. With these slides a risk is taken by the athlete.

At the conclusion of the program, the Data Entry Operator will read back the finalized elements to the rest of the Technical Panel and all related deductions for verification. The deductions are not limited to falls but can include others such as costume and time violations (there can be others). The time violation occurs more often than the costume violation. The event referee will confirm with the Technical Account the time of movement by the athlete. A common statement by the event referee will be “they didn’t stop sliding until…” Each level has a permissible allowance, and it varies from level to level and short program versus free skate. This information can be found in the US Figure Skating rulebook Rules of the Sport 6051 and 6052 for Singles.

Here is an important rule stated in the US Figure Skating Rulebook: 6050 Duration of Skating – Singles Timing starts from the moment the skater begins to move or skate. Timing stops when the skater comes

to a complete stop at the end of the program. This means that the body is no longer moving (i.e., no floating arm movement) and the entire body has come to a complete stop on the ice. A sliding movement can at times take too long to come to a complete halt on the ice.

Also with these sliding movements is the risk of a fall. The athlete typically doesn’t have any blades in contact with the ice and they could lose control for a moment or more. This could also result in a fall outside of an element and with the appropriate deduction taken. A fall is defined by the International Skating Union (ISU) and US Figure Skating as a “loss of control by a skater with the result that the majority of his/her own body weight is on the ice supported by any part of the body other than the blades, for example: Hand(s), knee(s), back, buttock(s) or any part of the arm.” It is not being suggested that knee slides are removed but coaches and athletes must be aware of the risks they are taking when performing them. Here again the movement must be trained and be consistent as all skating elements of the program.

In conclusion, it may be wise for all coaches, choreographers, and athletes to be aware of the various deductions that can occur within a program. These can be found in Rules of the Sport 1071 for Singles and Pairs. Think wisely about the knee slides so they don’t become the slippery slope to a deduction.

Denise Williamson (MFS, MM, SFF, CC) is the chair of PSA's Education Committee.

Denise Williamson (MFS, MM, SFF, CC) is the chair of PSA's Education Committee.

PSA Credits: 10

Led by PSA master-rated coaches, this course presents strategies to successfully navigate the world of coaching and optimize teaching potential. On- and off-ice sessions provide a foundation of resources and tools for both new and experienced coaches. Upon course completion, coaches earn the equivalency of a PSA Basic Accreditation (BA) exam. All participants receive a free copy of the Coaches Manual and non-members also receive complimentary PSA Basic membership for the current season.

FACULTY:

*MUST ATTEND 80% OF INTERACTIVE SESSIONS TO RECEIVE CREDITS

Registration is open November 1—December 31, 2023

The following is an article intended to provide you with an introductory understanding of contracts and how the terms and conditions of a contract may affect your profession. It is not intended, nor should it be interpreted, as legal advice. Before entering into any contract or agreement, we strongly recommend that you seek independent legal and tax counsel.

There is an old saying that says, “All contracts are an agreement, but all agreements are not contracts.” A contract is a promise, or a set of promises, to which the law attaches certain legal obligations. An agreement is an understanding or arrangement reached between two or more parties. An agreement or understanding is generally not legally binding as they do not possess the required purpose to be legally binding like a contract. An agreement does not necessarily need to be in writing and can be verbal. It is important to understand this distinction as not all in the skating industry use formal contracts.

The most common contracts in the skating industry are coaching contracts between arenas/clubs and coaches. Less common but equally important are contracts between coaches and their athletes/parents. Figure Skating Coaching Contracts are limited only by the reaches of your imagination provided that they are in compliance with the law, IRS guidelines, SafeSport and SkateSafe. No particular form is necessary to follow but

certain basic information must be contained in all contracts. The most important factor in any contract is to have an agreement which clearly spells out each party’s duties and obligations as stipulated within the contract. It is important to remember that in most states only an adult can enter into a contract.

When you work for someone else, you are under a “contract”. This contract may be oral or it may be in writing. An oral contract is just as binding as one in writing; however, the terms of an oral contract are generally much harder to enforce, and it is much easier for one of the parties to the contract to “forget” certain important parts of the contract which later erupts into a dispute. Also, some states prohibit oral contracts which provide terms that cannot be completed in a year or less. A written contract is preferred. “The most faded ink is better than the sharpest memory.” In fact, some states require a contract for personal service, such as teaching figure skating or coaching or class lessons in a rink, to be in writing.

The following are items that must be included in any employment or personal service contract. The items are not exhaustive but set the basic framework that govern such contracts. However, each contract should be reviewed by a licensed attorney in the state where the contract is to be performed:

• The name of each party to the contract.

• The date the contract is entered into between the parties.

• The payment to be made by one party to the other party is sometimes referred to as consideration.

• Specific terms of payment, i.e. weekly, monthly, semi-monthly and in the appropriate currency

• Where is the specific location the work is to be performed and how the payments are to be made for the work performed. For example, the check is mailed to your home, you pick the check up at the office, or some sort of direct deposit.

• The timeframe to complete the work.

• The general terms of the contract specifically describe the duties to be performed by each of the parties to the contract. For example, the duty of a professional may be to register students for the class, keep class records, operate the ice resurface machinery and otherwise do general bookkeeping duties. There should also be some mention of how much and what kind of advertising the professional may do. The employer of the professional may be required to collect funds for the classes, do mailing lists and pay for postage, to advise participants

* Did you know your PSA membership includes #=4 free E-Learning Courses?

of the class of the skating schedule, keep class lists and do advertising, general accounting and billing.

• Term of the Contract: The length the contract is to run and the date the contract terminates; or that the contract shall continue until one or the other party gives a certain specified notice of an intention to no longer go forward with the contract.

• Damages in the event the contract is broken by one or the other party, or as sometimes appear in contracts, a specific statement indicating that no damages will be payable, if, for example, the ice resurfacer breaks down or the ice making machinery quits or if there is act of an God (usually some weather disaster) which terminates the useful life of the building or equipment.

• Liability for injury caused to one or the other party through accident or liability claimed as a result of the third party. For example, a student or a parent or a combination thereof sue the professional or the manager or both for the same claimed act of negligence which caused damage to the third party. A specific clause should be inserted in any employment contract which provides that there will be insurance to protect the professional in the event of such a lawsuit, and the insurance will name the employing unit as a “named insured '' along with the professional. Also try to have a clause that limits the professional’s liability to the limits of the insurance.

• Good Standing and Insurance: A requirement that the coach is in good standing with its regulatory body and the Coach is able to obtain and maintain liability coverage insurance.

• A place for the professional to sign his or her name and a place for the employer to sign their name and date of the contract as to when it is signed.

In contract matters, as all other matters related to written agreements, it is good business to contact an attorney and obtain their professional advice prior to signing the agreement. It is a very poor policy to engage the services of the attorney who is also representing a municipality or a rink owner. It is also important, you should spend time yourself reviewing the contract. Find a quiet place to read the document thoroughly and note comments, questions, and notes for clarifications. After you have completed your review, schedule a meeting with the other party. Take your time reviewing with the other party to confirm that you are both on the same page. It is within your rights to negotiate if you differ on specific terms.

If you are unhappy with the contract presented to you for signing, do not sign it; change it. Just because it is on a printed page does not mean you cannot alter in any way you see fit to reach a fair agreement. If a contract is written, there is a presumption that any party who signs the contract is agreeing to be bound by the obligations as set forth in the contract. It is generally not permitted to prove what your intention was under the terms of the contract after the

contract is signed. A party to a contract who had an opportunity and had the ability to read the contract may not be able to avoid performing under the terms of the contract by claiming lack of knowledge of the contents. The moral in this situation is to read and understand everything which is set out in the contract.

A contract is an important legal instrument for a coach and serves two purposes. First, it sets the ground rules for the coaching relationship so that both parties know their obligations. Second, it keeps the liabilities of the coach to an absolute minimum. A simple contract gives both parties peace of mind and, in the event that the employer (or in some cases, client) is unhappy, it offers the coach some protection.

Many coaches, like other freelance providers, do not establish the relationship on a business level, believing it to be unnecessary or that it may give an overly formal impression. To the contrary, a contract demonstrates that you are a professional, and that also applies to the coaching relationship. This can assist in keeping a professional objectivity and respect in the relationship on both sides.

Coaching promotes the idea of being proactive so, practice what you preach and ensure that both parties sign a contract before commencing the job as the coach.

Note It is a good policy to note what and how expenses will be invoiced in regards to competitions, test sessions, and shows/exhibitions.

Itwas an overcast yet slightly warmer-than-usual mid-January Sunday afternoon in Boston. Mildly concerned that I would miss my flight out of Logan airport in just a few hours, I still made my way to the front row of TD Garden to watch the Men’s Free skate at the 2014 U.S. Figure Skating Championships. I scrambled past a small Japanese man who spoke little English — at least to me. Other than awkwardly polite nods and small smiles we barely interacted over the next two hours.

Then it happened. A 19-year-old white Jewish skater took the ice to perform his Irish-American themed program created by an Afro-Latino choreographer and polished by the Midwestern woman who coached him. Before Jason Brown could finish his final spin, I, an African-American woman uncontented with merely applauding, had leapt to my feet while simultaneously the Japanese man to my left sprung from his seat. Overwhelmed by what we had just experienced we hugged each other while jumping up and down. Through not only technical skating elements, but by incorporating all the core dance components (Body, Action, Shape, Timing and ENERGY) paired with vibrant costume design, Jason Brown, Rohene Ward and Kori Ade had woven the tapestry of a compelling and successful program. Such is the power of a wellconceived, well-constructed, well-executed figure skating program. And, the audience loved it.

But, were we all wrong? Does a Jewish guy get to skate to Riverdance? Should an African American of Puerto Rican descent interpret a decidedly Irish American dance style? Is green costuming too cliché and stereotypical in depicting Irish culture? Was I as an African American supporting cultural appropriation at the expense of Irish and Irish American people? Were we all supporting the appropriation of culture?

Noun

1. The unacknowledged or inappropriate adoption of the practices, customs, or aesthetics of one social or ethnic groups by members of another (typically dominant) community or society.

Oxford English Dictionary, March 2018

What is cultural appropriation? How does it differ from cultural appreciation and cultural exchange? Who gets to decide?

Three items are central to the concept of cultural appropriation:

First, the use must be outside of its original cultural context.

Next, an imbalance of power must exist between the person or people using a cultural aspect and the people from which it is drawn. Typically, this is the dominant social or economic community drawing from a marginalized community.

Finally, the use must be inappropriate when seen through the lens of the originating group and/or the originators are unacknowledged.

Conversely, cultural appreciation and cultural exchange are respectful and require an understanding and acknowledgement of the source material.

In a creative context some wonder if concerns about cultural appropriation even matter. Why not use music from another culture, or add in some exotic movements, use a cool symbol on a costume or juxtapose elements from several communities? Isn’t that what being creative is all about? Isn’t imitation the highest form of flattery?

Sadly, no. Cultural appropriation is exploitative.

Even when the manner of use is not overtly

negative, it is still disrespectful to use something of value that belongs to others without credit or compensation. Too often people are marginalized and belittled for customs and aesthetics that when adopted by people from outside their community are

“

Every culture’s history is essential. Everyone deserves to have their lives elevated through the beauty of truthful representation.” - ROHIT BHARGAVA

lauded. For example, Black women have long been told that wearing their hair in protective styles such as braids, locs, or knots is not professional. Many workplace dress codes specifically banned these styles. However, when non-Black women such as Kim Kardashian (and Bo Derek) wore them, these styles were considered new and trendy.

Cultural or religious icons may have sacred or important meanings that require use only in a very specific context. Use outside of those contexts or by

the timing of elements and shapes we make are not random. This synergy of art and athleticism is grounded in a rich history of proven technique. We take the time to learn about elements and how they connect.

We must be no less diligent in our use of components derived from other cultures. Because even when easily mimicked, styles, rhythms, poses, and movements are grounded in cultural context. Use of cultural elements without context is not creativity; it is caricature.

Building a strong program takes time. Use some of that time to learn authentic origins; appreciate cultural context; consult experts and compensation them; incorporate respectful usage; and acknowledge the sources you draw from. Don’t use fear of the hard work as an excuse for exclusion and exploitation.

people who are not members of the community is disrespectful and often offensive. Further, marginalized communities typically lack access to markets to monetize their creativity. When people from outside of the community benefit financially while people within the community could not disadvantaged people are further exploited.

Cultural appreciation and exchange require respect and effort. As coaches and choreographers there is the constant challenge to create something fresh, new, or different. Each season becomes increasingly complex. Coaches must teach jumps with more rotations; spin with greater variety and difficulty; develop intricate, yet proscriptive footwork; keep up with constant rule changes; and train younger and younger athletes. All of this must be done under the time pressure of a never-ending training cycle and crammed into a few short minutes. Under pressure to innovate, it is often tempting to look to the latest fad or copy a style with little thought of its cultural context.

As skating coaches, we train our students to understand the use of their bodies, the importance of specific movements and isolations. We understand that

Do the work to truly learn about other cultures from its members. In doing this it is important to remember that no one person or small group is the keeper of culture. But, through research and engagement we can learn to appreciate different cultures in their context. This sharing of information can lead to authentic cultural exchange.

Jason Brown’s Riverdance at 2014 Nationals went viral. It was viewed online over 3.5 million times. That is the stuff that makes coaches’ dreams and careers. Music selection, program concept and construction can make or break a skater’s season. While trying to create “that moment”, we should not fear trying something new. But, like other aspects of skating cultural exchange takes work.

The next article in this series will provide more information how to avoid cultural appropriation and promote cultural appreciation — including tips from other coaches and choreographers.

“ All cultures learn from each other. The problem is that if the Beatles tell me that they learned everything they know from Blind Willie, I want to know why Blind Willie is still running an elevator in Jackson, MS.” - AMIRI BARAKA

“ Borrowing from other cultures is inevitable, but there are positive ways in which it can be done. We should engage with other cultures on more than an aesthetic level.” - RUKA HATUA-SAAR WHITE

“ Use of cultural elements without context is not creativity; it is caricature.”Darlene Lewis (CM, RFS, RG) is the chair of PSA's Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion committee.

Drum roll, please!

Sound the cymbals for Kathryn Vaughn

PSA's first candidate to take and pass the new Registered Solo Pattern Dance Rating

Congrats, new masters!

Katherine Erickson

Master Group

Brenna Greco

Master Group

Gloria Leous

Master Free Skate

My son Cole is many things. What he is not is shy or unmotivated. A 28-week triplet who had a major stroke and 13 brain surgeries, Cole has more than eight diagnoses of which the main two are Cerebral Palsy and Autism. From the moment he was a sickly NICU baby, he exuded a charming personality that has been a grace bestowed upon him. We always jokingly say, “He’s never met an audience he doesn’t like.”

Truer words were never spoken. As a former lifelong skating competitor and a long-time coach, I put my kids on the ice at age two because I could. I knew that skating and horses were the two sports that most mimic the human gait. Thus, while I had no expectation of my children becoming skaters or competitors, I knew it could not hurt. Over time, Cole learned how to do things on the ice, with me holding him up.

Seven years ago my other son, who had dabbled in skating,

decided to be a competitor. As an announcer for many years, I knew many fellow officials and called the referee at a local event to ask if they could find a place in the schedule for Cole to compete. The answer was yes and we set about creating something Cole could do, with me behind him. He started calling me his ‘prop’. Every competition his brother did, Cole did as well. We started getting more and more creative with the themes and I noticed Cole gaining strength in his movements.

In 2019 Cole suggested we skate together—not just me assisting. We made use of his former gait trainer—a hybrid wheelchair-bicycle seat device that helped him learn how to walk by the time he was five—that gave Cole something to stand up with while I attempted to resurrect my former skating skills. The video went viral on YouTube— gaining over three million views— and we received many messages asking where people could obtain a similar device for ice use.

I realized then that Cole

had more to offer the skating community, especially in terms of encouraging other adaptive skaters to participate. In 2021, National Showcase decided to include adaptive entries for the first time. Cole entered and flourished under the spotlight, relishing the huge audience and appreciation for entertainmentbased skating competition. The following year, he and wheelchair-bound competitor Rob Hanley performed the first-ever Showcase Adaptive duet. U.S. Figure Skating National Showcase NVC Daren Patterson was instrumental in offering these opportunities. We had three starts in 2021, six starts in 2022, and are looking forward to what lies in store this summer!

As Cole received feedback from a judge for the first time last year, my heart practically beat out of my chest as I stood back and observed the moment. He

listened intently as judge Ann Buckley declared he had "reached the top of the bleachers" and as she discussed suggestions for enhancing his craft. Upon hearing her assessment, he gave his signature huge and charming smile.

As a parent, I am incredibly grateful for my child to have this outlet. As a lifelong skater and U.S. Figure Skating committee leadership participant, I am ecstatic that our efforts as an organization have made room for this group of skaters. Cole is a Shriners Hospitals Ambassador, a USFS #GetUp Ambassador, lettered in choir at school, and does adaptive dance and baseball. He is incessantly motivated and inspired by creativity and always thinking ahead to what skating programs he can do and how to do better than the previous year. He holds nothing back.

This is not about me, but rather, opening doors for him

to get through. From the time he was little, I barely got a door open that he hasn’t charged through on his own steam, asking for help when he needs it. With my competitive and coaching careers in the rearview mirror, this has been a new and unique way for me to be on the ice. I have the honor of being Cole’s "prop" with an up-close spot to watch my kiddo grow into his own, connecting with audiences from his heart, and hopefully inspiring others to join us. I am the luckiest mama.

@TEAMTODDANDJENNI

Todd got to see all of his “kids” today for the first time since March. It was an emotional day for sure. We are so grateful to have this special group…our Great Park pairs family... #sandmanstrong #standyourground

In the field of championship figure skating, it is rare that any competitor works with only one coach.

So, it is not surprising that the 2023 PSA Coach of the Year is, in fact, a team of four coaches, three of whom won the award together previously in 2020.

Todd Sand, Jenni Meno Sand, Chrstine FowlerBinder and Chris Knierim were selected as the 2023 PSA Coach of the Year for their work through

BY KENT M C DILLthe previous year, including the 2022 World Figure Skating Championship for Alexa Knierim and Brandon Frazier.

“We were very honored to win the award,’’ said Jenni Meno Sand, speaking for herself and her husband Todd, who suffered a heart attack in March and is still recovering. “We are a great coaching team, and our athletes put 100 percent trust in us, doing whatever we ask of them. We have great families that

support us as well. We are really fortunate for that.”

A team of skating coaches is often asked to delineate the coaching duties involved, but the Sands and Fowler-Binder have been together for 17 years, so that the separation of duties is less important than the combined efforts of the coaching talents.

“Jenni is more of the manager, and Todd is the detail person, handling the technical as well as the finishing programs,’’ Fowler-Binder explained. “He is always reading coaches and books and studying coaching philosophy. Chris helped a lot with twists and lifts. I work with polishing programs.”

The team works from the relatively new and huge facility in southern California, the Great Park Ice and Fivepoint Arena in Irvine, which was created specifically to serve training for pairs.

Chris Knierim worked with the team for three years, but moved with his wife Alexa back to her Chicago area hometown and now operates from the Oakton Ice Arena in suburban Park Ridge, Ill.

Knierim’s absence with the team has been filled by Frazier, who provides the youthful coaching point of view previously provided by Knierim.

In 2022, the Sands-Fowler-Binder-Knierim team coached champions at Junior Worlds, Junior Nationals and Novice Nationals.

“I think we were selected for our coaching season as a whole,’’ Sand said.

Thank you to the athletes for sharing photos and words.

“Finding your home both on and off the ice can be hard for any athlete. Starting with Todd and Jenni in 2019 opened the door for me to find a training camp founded on love and support. Brandon and I reached our dreams becoming World Champions by trusting our incredible team of coaches.”

Alexa Knierim

Alexa Knierim

“Training with this team has taught us so many lessons that we will cherish forever. Something Todd has taught us is to always give it all we've got—no matter the circumstances—and to never back down. They push us to our limit everyday and it is an honor be a part of this team. Thank you for this opportunity to speak about our amazing team!”

Ellie Korytek and Timmy Chapman“Todd and Jenny's team is my second family. Todd is always focused on details and safety for girl partner. He’s very big on that! Jenny is always there for me for pep-talk or nice push when I need it. Christine is the happiest coach I know and a huge cheer leader for all of us on an everyday basis...Todd and Jenny created an atmosphere of high standards, hard work, and full support between the skaters and coaches. I couldn’t be more grateful for sharing the ice with my teammates and I love my coaches forever!”

Sonia Baram

“How did I get here?...I applied myself. I loved what I was doing.”

When one is asked to consider their lifetime, they may concentrate on the passage of time, remembering where they once were and ruminating on how they got to where they are today.

But a lifetime is made of moments. Taking time to consider the most important moments of your life will get you to the same eventual place, perhaps with a greater appreciation of what you went through.

It’s similar to the question of looking at the forest or at the trees.

Debbie Stoery, one of the most learned technical figure skating coaches in the history of the sport, is the honoree of the 2023 Professional Skater’s Associationi Shulman Award for LIfetime Acheivement.

In a wide-ranging conversation with PS Magazine, Stoery considered her lifetime in skating as a whole while pointing at particular moments along the way that make her story compelling.

Let’s start at the very beginning Stoery was born into a family of figure skaters. Her mother was a member of the Chicago Professional Skater’s Club and ice-danced with the Skokie Valley Skaters Club. Her father was

President of the Wagon Wheel Figure Skating Club (an organization which to this day maintains connections through a running email conversation). Her sister was an accomplished competitor in figures, freestyle and ice dance. Her brother grew up to work as an ice skating equipment provider. Debbie herself had been coaching since the age of 17 at the Northbrook, Ill., Sports Center, where she is currently on staff.

After high school, Stoery took a year off from formal education to concentrate on being a figure skating coach and judge. But college called to her and she enrolled at Northwestern University, working toward a degree in theatre and interpretation. She was also pursuing a dance minor, and was studying music and dance theory.

She then had the first pivotal moment of her coaching life.

In May of 1972, at the age of 18, Stoery attended the first Professional Skater’s Guild of America convention In New York. There she heard from guest speaker Dr. Margery Turner, a professor from Hunter College. The topic was “What you should study if you are serious about coaching.”

BOOM!

“Some of the items she listed were already in my dance major,’’ Stoery said. “But her list included kinesiology. I found the sports science curriculum at Northwestern, and I became very enthusiastic about pursuing that information, especially the respiratory

response to exercise.”

Stoery made a habit of attending every major figure skating competition she could, even though she had no students of her own at those events. In the winter of her sophomore year at college, she attended the U.S. National Championships and boldly chose (she likes to say “had the balls”) to introduce herself to former Olympic champion and then famed coach Pierre Brunet, who was in the States working with Janet Lynn. “I asked him if I could serve an apprenticeship under him, and he told me to call him after the World Championships.”

Which she did.

“So I took off the spring quarters of my sophomore and junior years at Northwestern to understudy with him, taking on ice lessons, bringing my students to work with him, observing his lessons with students, and then enjoying afternoon tea in the rink cafe watching him draw diagrams on napkins. I was a young, intelligent and enthusiastic coach in the right place at the right time.”

It probably is more accurate to say she put herself in the right place at the right time. She was not one to have events happen to her. They usually happened because of her.

Stoery’s pursuit of an understanding of the science revolving around figure skating

allowed her to reach unique levels of coaching expertise. Her list of accomplishments is long and varied. She revels in the outcomes of her work while trying to downplay her own importance in the events.

In 1976, Stoery became the youngest coach (24) to pass the Master Rating in Figures and Freestyle before a judging panel of five men (she credits her time with Brunet for being skilled enough to pass). She was the first coach to take any Moves in the Field exam, doing so in front of a panel of judges who were the co-inventors of the Moves.

She became a judge for Masters exams, and she discovered “the real blessing has been to affirm the devotion that each candidate embodies in the pursuit of excellence, whether passing or not.” With that attitude, she employed the thinking of Ralph Waldo Emerson, who told us “it’s the journey, not the destination”.

In 1975, Stoery was asked by Nadine Eliott to become the first editor of the PSGA newsletter, despite having no journalism nor editorial background. In the 1980s, Stoery was asked by Kathy Casey to join the PSA Technical Committee, during which she placed herself in the eye of a storm as she publicly defended the possibility of eliminating school figures from the skating curriculum.

Stoery’s role with the PSA again indicates her open-hearted attitude toward the science of skating. Stoery spent five years as the Chair of the PSA Sports Science Committee, while working with her skaters and providing scientific insight to other coaches in the form of articles for the PS Magazine. She developed a 20-page handbook the PSA turned into the United States Olympic Committee in order to receive a significant Sport Sciences grant for the PSA.

When she turned 60 years old, she did what anyone might do at that stage of life: she

Debbie accepts her EDI award at the 2023 banquet in May.

Debbie and Denise Williamson

Debbie accepts her EDI award at the 2023 banquet in May.

Debbie and Denise Williamson

re-enrolled at Northwestern University to take classes in neurophysiology and neuropsychology. “My educational goal has been to be able to ask the right question to the right people and understand their answers,’’ she said to explain her academic pursuit.

Pointing directly to her work as a technician, Stoery had four students recognized as the first in the world to perform a specific technical element—at Junior Worlds in 1980 and 1982 and at two other U.S. competitions in 1984 and 1985. “I do feel that anyone in any sport who breaks a barrier is making a significant contribution that far exceeds the value of merely winning,’’ Stoery said.

Over the years, Stoery played a role in the development of Olympic skaters including Caryn Kadavy, Nicole Bobek, Melissa Gregory and Evan Lysacek.

Stoery is very quick to point to her academic prowess and ability to learn quickly as a key contributor to her success as a skating coach. At the same time, she is extremely uncertain exactly why she was honored as the LIfetime Achievement award winner for 2023 (she had been nominated twice before).

“My personal expectations were extraordinarily moderate,’’ Stoery said. “I felt so fortunate to be gifted as an academic prodigy. So many things came easily to me, not as a skater but as a coach. But I didn’t trust my own ability to succeed.

“My first goal was could I teach an axel,’’ she said. “Then I found myself the youngest person to ever pass the master rating, the youngest person on our international team, and I

wondered “How did I get here?” My only answer to myself was I applied myself. I loved what I was doing.”

Stoery’s coaching philosophy lies at the heart of her own attitude toward education.

When she first learned Moves in the Field, Stoery accepted the system while fussing out ways to improve it. “I would always look for the advantages in a new system rather than reject it,’’ she said.

As a coach, Stoery expected her skaters to think for themselves rather than just take the coach’s word for what was expected. “My goal is that (her skaters) have the knowledge base and the desire and expectation to improve on themselves. My greatest moment is when a skater comes by and asks if they can show me something they have been working on outside of my influence.”

Today, Stoery continues her coaching by covering a wide swath of the northwest suburbs of Chicago, working at rinks in Glenview, Northbrook, Winnetka and Wilmette. She is also planning her own October wedding. “I have wondered why I was chosen for this award,’’ Stoery said. “I hope that I was chosen on the basis not only of my achievements but rather largely in consideration of the character and dignity that I have displayed on a consistent basis. I know that I have contributed locally and globally to coaches’ education, set an example of prioritizing athlete health and safety, promoted academic interest with enthusiasm, and earned the trust and response of my students because they know that I cared about them as people.”

Team PSA is made up of:

• grassroots coaches

• rating examiners

• full-time coaches

• learners

• Area Representatives

• creatives

• program directors

• you!

Thanks for making our team so special.

Hey Professional members — did you receive notice about a PSA TV subscription without signing up? Don't fret!

That’s because you receive a one year FREE subscription to PSA TV with your Professional membership—in addition to a printed copy of the PS Magazine, three free PSA webinars, and so much more. If you have any questions or need assistance, please reach out to Charmayne at ccochran@skatepsa.com

Charlie Cyr was an ultimate influencer in the sport of Figure Skating. Born on February 17, 1955 in Edmundston, New Brunswick, Canada, he grew up figure skating and competed in high school ski team and tennis team. After graduating from the University of Maine he went to Central Maine Medical Center and completed his degree in radiology technology. Eventually, Charlie moved to Palm Desert, California to work at Eisenhower Medical Center. While working at Eisenhower, he met his future wife Jolene. Charlie and Jolene married on February 14, 1981.

Charlie worked at Eisenhower for 40 years in various capacities including special imaging, OR assistance, Practice Administrator, and Medical Researcher. He felt lucky to be able to combine his passions of Figure Skating and medicine and became an ISU Judge for Single Skating, Pair Skating and Ice Dance, a Referee, and a Technical Controller. He judged Ice Dance at the 2010

Olympic Winter Games in Vancouver and served as a Team Leader for the 2002 Olympic Winter Games in Salt Lake City for U.S. Figure Skating. He also contributed to the creation of the ISU Judging System. In 2014, Mr. Cyr was appointed ISU Sports Technical Director Figure Skating and contributed significantly to the development of Figure Skating in this capacity until he resigned in 2023 due to health reasons.

Over the years, Charlie was a frequent presenter at the PSA’s Conferences. He was also the technical adviser for U.S. Figure Skating’s Skate Radio.

Charlie passed away peacefully on the evening of June 22, 2023 at home in Palm Desert, California surrounded by his wife of 42 years, Jolene, daughters Allison and Ashley, son-in-law, Sam Albrecht, grandchildren, Sadie and Rhett, and family dog, Miska. The family requests those who wish to express sympathy to consider making a charitable donation to his daughter's nonprofit at: twenty4change. org, U.S. Figure Skating at: 1961memorialfund.com, or a charity of your choice.

Charlie was one of a kind. His hard work, integrity, determination, kindness, contagious laugh, and stories will continue to live on within us. Our lives are better because of Charlie, may he rest in peace.

Vanessa Anderson

Brianna Anderson

Starr Andrews

Jadranka Andricic

Brianne Arendt

Kareese Arneson

Calista Bailey

Alexandra Balderrama

Juliana Barshay

Juliana Bent

Lily Bishilany

Lauren Bjerke

Sjoukje Brown

Madison Chastagner

Nicole Christou

Elouise Cornwell

Imogen Croft

Alexis Ells

Sophia Farajallah

Cameron Feeley

Nadiia Frolenkova

Emily German

Kristiene Gong

Lia Grabovenko

Vanessa Griffin

Kaitlyn Guion

Alice Hamilton

Kianna Heller

Natalie Hodinko

Ashlyn Johnson

Isaac Jun

Andrii Kapran

Laura Kasinof

Marissa Klein

Grace Lee

Natalya Loktionova-Manning

Rebecca Lucas

Margaret Lynch

Nicholas Mangone

Maria Manley

Josephine Martin

Riley Mathieson

Amy Maurice

Mykhailo Medunytsia

Ambryn Meehan

Christopher Miller

Aricka Mitchell

Kelli Hagen

Kim Idland

Derrick Delmore

Chris Knierim

Lisa Henning

Jimmie Santee

Jimmie Santee

Marina Akbarov

Jennifer Schneble

Allison Hatch-Higgins

Jimmie Santee

Jimmie Santee

Renae Sundgren

Blake McGee

Courtney McCullough

Ashley Wyatt

Jimmie Santee

Yesenia Naranjo-Gilroy

Otar Japaridze

Ashley Tomich

Alexei Kiliakov

Jimmie Santee

Sean Rabbitt

Jimmie Santee

Jimmie Santee

Megan Endries

Corey Mjaatvedt

Kayla Tennant

Jennifer Schneble

Lacie Tew Maisey

Gabriella Vinokur

Jimmie Santee

Caroline Summerlin

Jennifer Howland

Justin Kozikowski

Cynthia Van Valkenburg

Caroline Summerlin

Allison Phillips

Jamie Jones

Alana Christie

Katelyn Rew

Stephanie Solano

Allison Phillips

Johnny Weir

Julie Brinskelle

Ashley Wyatt

Jimmie Santee

Camille Moberg

Gina Moser

Berlin Mossak

Aislinn Munck-Owen

Lucille Nomaguchi-Long

Gwyneth O'Rourke

Meagan Oleary

Devon Olsen

Kathryn Olsen

Ryan Orr

Hannah Osborn

Saskia Oudejans

Savannah Paisley

Madison Paxton

Patricia Plum

Laura Pursell

Emily Rickard

Christine Robinson

Gabrielle Roman

Nicole Rudolph

Armen Saakian

Chealsey Sanchez

Kaitlin Sauer

Breanna Schmanski

Stephanie Scott

Lily Scott

Lucille Sherman

Shelzene Shinn

Holly Sperling

Lauralee Stanton

Veronica Staron

Kelsey Stouffer

Sophia To

Dana Tracy

Ella Uhde

Emilija Vaiciulis

Elizabeth Walker

Emma Watkins

Ania Weglicka

Gabrielle Werner

Elyse Wiese

Alexa Winter

Alan Wong

Robert Yampolsky

Anna Yau

Lorissa Zhou

Elizabeth Zoeli

Cindi Ezzo

Ellen Bennett

Debbie Warne-Jacobsen

Rebecca Stump

Jimmie Santee

Denise Hughes

Peter Biver

Kyoko Ina

Erin Egelhoff

Jimmie Santee

Andrea Auer

Jimmie Santee

Jimmie Santee

Ruslan Goncharov

Klaranda Behrens

Becki Hendren

Kayla Tennant

Jimmie Santee

Jimmie Santee

Vage Evetts

Laura Galindo

Kayla Tennent

Cindi Ezzo

Jimmie Santee

Michele Steinberger

Ashley Tike

Denise Hughes

Jimmie Santee

Holly Malewski

Kayla Tennant

Jimmie Santee

Jimmie Santee

Daniel Chambers

Kelli Standekar

Alana Christie

Jennafer Reimann

Laura Marunde

Paula McKinley

Jimmie Santee

Jennifer Schneble

Jun Hong Chen

Jimmie Santee

Alexei Sidorov

Jimmie Santee

Alec Schmitt

Jimmie Santee

Morgan Bell

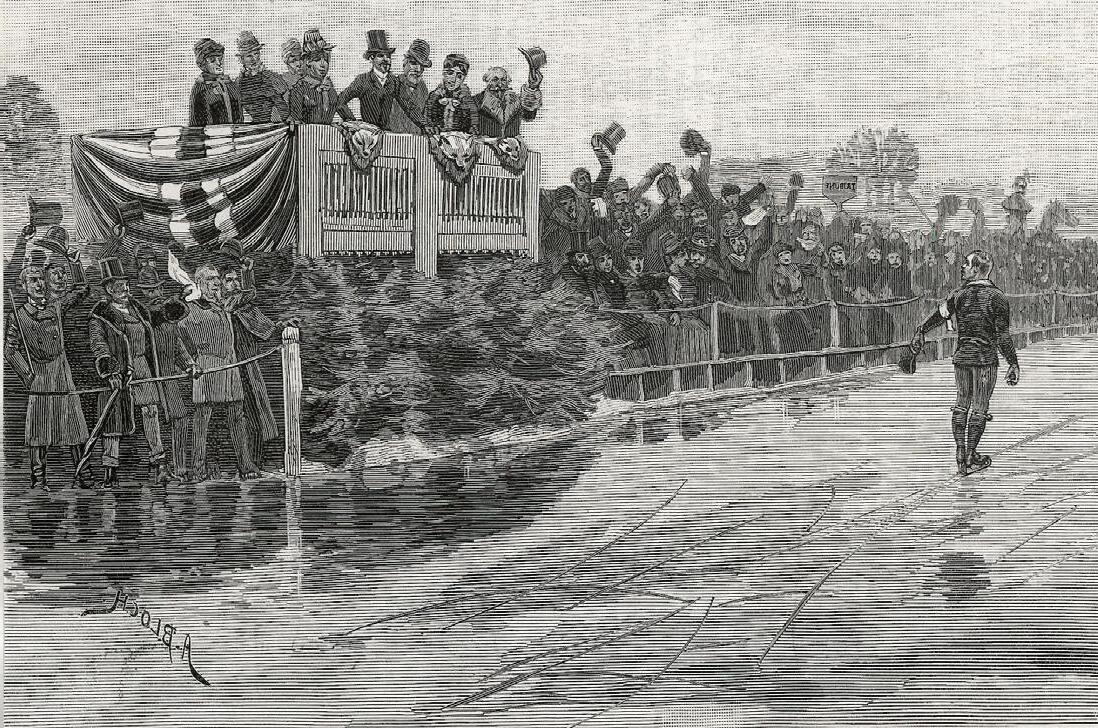

fter the sensational and rousing antics of the January 1st race between Paulsen and McCormick, the next race was scheduled for January 9, 1890, at the Palace rink. Again, the stakes were for $250 a side and a split of 65/35 of the gate receipts. The five-mile race was short enough to allow almost a full effort from start to finish. If Paulsen were to win the race McCormick loses all chances for the championship. If McCormick wins his chances for the championship looked even better. Also, because of the shenanigans that played out during the first race, the track was roped all the way around on the outside, and the chairs on the corners, replaced by flags. As for the starting positions, considerable debate ensued.

A reporter for the Minneapolis Tribune went to Paulsen’s cigar factory on Cedar Avenue and interviewed him. Paulsen preferred that they start from opposite sides of the rink. Paulsen pointed out that "dogging" done by McCormick in the first race could not be repeated, and both men would be compelled to take an equal amount of "wind pushing." The amount of wind Paulson broke on Wednesday ought to be a lesson to him and lead him to contend for the principle of starting opposite so earnestly that he would finally gain the day. Finally, Paulsen requested that the rink add 10 more electric lights for use on the night of the race, saying, “He does not propose

to skate at full speed on a 7 ½ lap track unless it is properly lighted.” When asked if he would win the second race, Paulsen responded: I am going to skate pretty hard and hope to be quite well by that time. I am considerably handicapped. In the first place the race takes place in the evening when it is very difficult for me to skate fast, as I am very nearsighted, which makes it hard for me to distinguish things with certainty. In the second place, as I have said before, the rink is too small for me but is just suited to McCormick. The majority of Canadian rinks are small, some even requiring 17 laps to the mile. To these rinks I, on the other hand, have made my best time on rinks of three or four laps or else straightway. Continually turning corners requires a different motion and also a special training… If I lose Wednesday's race I propose to have something to say about the place of skating the last race. I have agreed to McCormick's terms twice, giving him the advantage. In all probability, I shall decide on Eau Claire as the place of the last race. I shall also insist on McCormick and myself starting at different points. I hope then to

beat him without difficulty, unless an accident should occur. I want to say that the abuse I have received lately in the daily papers of this city is uncalled for and many of their statements are incorrect and unjust.

Regrettably—or conveniently?— Paulsen became sick and the race was postponed. According to his doctor, he respired too much cold air and woke up the following day sick. After meeting with the organizers and McCormick, the race was rescheduled for the following week. An interesting note was a comment in an earlier article stating that Paulsen was doing everything he could do to not race McCormick. It sure seems like that?

It was reported that 700 spectators attended the second race which was won by McCormick. Starting quickly, he gained a full 100 feet on Paulsen, who on the second lap fell, losing another half of lap. With all the buildup in the newspapers, it was disappointingly over in the first lap. The following week, Paulsen was to appear at the Red Wing rink and failed to appear, making it the second time he failed to keep an engagement for his appearance in that city.

As stated in the initial agreement, the third and deciding race was to be skated on ice that was selected by Paulsen, who picked Half Moon Lake in Eau Claire, Wisconsin. After several postponements, the race happened on February 2 in front of 4,000 people. The Wisconsin Central ran a special train of nine cars from Minneapolis and it was loaded to standing room. Paulsen was backed heavily by friends in Minneapolis and elsewhere. Considerable money, perhaps $1,200, was wagered. As he had in each previous race with Paulson, McCormick wagered every dollar he had won in previous races on the result of the final race.

To his advantage, Paulsen had been at Eau Claire the week before and laid out the course of the track himself. The track was a trifle over three laps to the mile and when the race came, was an inch deep in water and slush. Had either Paulsen or McCormick seen the track before the anxious 4,000 people had

been admitted, it is likely the race would never have been skated. Paulson skated a lap, and objected to the “sharpness of the corners.” McCormick’s manager countered by showing a certificate from the surveyor who had laid out the course. Paulsen insisted that the flags should be moved back, but the friends of McCormick would not allow it. Once the race was ready to go, a false start was made owing to Paulsen’s failure to get his coat off. Paulsen did not start but McCormick did and flew past the judge’s stand. He came back however when his manager, McEvoy, waived the start, and after a good deal of loud talk between McEvoy and Jungen, Paulsen’s manager, a fair start was made.

McCormick followed the strategies he used so successfully in the second race and went for the win from the start. In going four laps he caught Paulsen and from that time to within two laps of the end “dogged” him. Though the spectators shouted to McCormick to go and "beat him a mile," he kept right behind Paulsen until the 31st lap when he charged forward and gained enough distance to win by a third of a mile.

Paulsen, however, was not satisfied with his defeat and within a week issued a challenge; 10 miles on a track of three laps or less per mile, on Lake Minnetonka the following Sunday, he would put up his gold world championship medal and $400 a side, winner take all. Furthermore, no gate receipts and all expenses paid by himself. Paulsen—through his representatives—also made the following demands in their challenge:

That the track shall either be two laps to the mile and square or three and one-half laps and oblong, the shape of the Eau Claire track, with the corners rounded. They also suggest that each man select a representative business man of either Minneapolis or St. Paul,—the two to choose a third, who shall decide upon the correctness of the measurements of the track and whether or not it is in proper condition to skate upon on the day of the race. Paulsen will

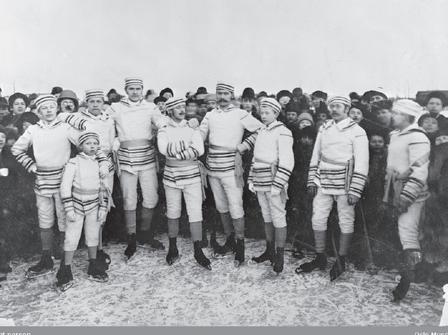

Axel Paulsen, second from right, and his brother Edvin, far right, are photographed in Norway around 1870.

Axel Paulsen, second from right, and his brother Edvin, far right, are photographed in Norway around 1870.

SEPTEMBER

Date September 6, 13, 20, 2023

Event Webinar - Quick Start Your Hockey Season

3 PSA Educational Credits

OCTOBER

Date October 1, 2023

Event PSA FREE E-Learning Membership Course Available (#2)

Credits 1 PSA Educational Credit

Date October 4, 2023

Event FREE Webinar – Understanding IJS Rules No Test through Juvenile

Credits 1 PSA Educational Credits

Date October 15, 2023

Event Virtual Ratings – FULL

Credits 1 PSA Educational Credit

NOVEMBER

Date November 1

Time 12am Central Time

Event Registration OPENS for February Virtual Ratings

Registration OPENS for January Virtual Foundations of Coaching Course

Date November 17-19, 2023

Event Virtual Ratings – FULL

Credits 1 PSA Educational Credit

JANUARY 2024

Date January 9, 16, 23, 30 and February 6, 2024

Event Virtual Foundations of Coaching Course

Credits 10 PSA Educational Credits

FEBRUARY

Date February 9-11, 2024

Event Virtual Ratings Exams – all disciplines and levels

*Exception is Synchronized Skating

Credits 1 PSA Educational Credit

The Cleveland Skating Club is looking for an Ice Rink Sports Director to oversee our Figure Skating, Learn to Skate, Curling, and Hockey program. Any questions should be emailed to bjones@clevelandskatingclub.org

You can upgrade your membership at any time!

As a member of PSA, you have access to educational events, valuable resources, and member discounts. All three membership categories offer the following benefits:

• Free PSA E-Learning Courses

• Member rate for events and merchandise

• Accreditation opportunities

• PSA Today monthly e-newsletter

• PS Magazine

In addition to those base benefits, the Community and Professional tiers include access to PSA TV, free PSA Webinars, and Accelerated Coaching Partnerships (ACP). The Professional membership holds further exclusive perks.

Visit

Did you know?

PSA's Professional membership is the only category that meets U.S. Figure Skating compliance requirements. It is also the only enrollment option that receives a printed version of PS Magazine and includes a one year subscription to PSA TV.