5 minute read

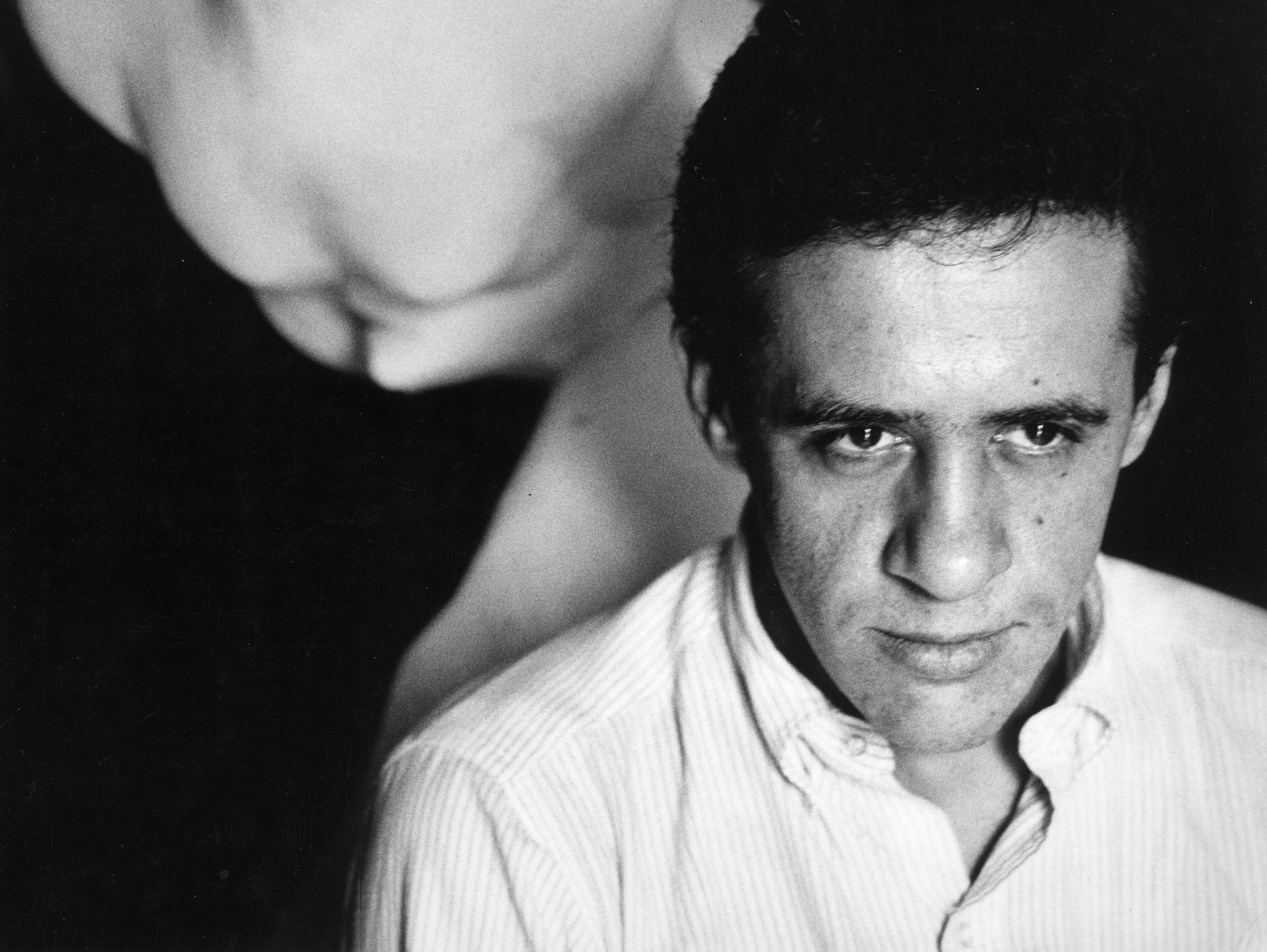

Portrait of an Artist: RICHARD PEPITONE (1936–2022) by Bill Evaul

Artist with sculpture Flight in 1968. Photo by Lynda Bartlett.

A small card posted on the bulletin board at the Fine Arts Work Center caught my eye. It read, “Sculptor seeks studio assistant—$5.00 per hour.” This was the early seventies, mind you, and a good carpenter was only getting $3.50 per hour. My fellowship stipend was good, but not quite enough to make ends meet, so I called the number and soon found myself working for the sculptor Richard Pepitone. This was the beginning of a nearly fifty-year friendship.

Advertisement

At that time Richard was making casts of live models in plaster, creating molds from the plaster negatives and then casting figures and fragments of figures in polyester resin. This was a laborious process, and he handled every step with meticulous craftsmanship and artistic vision. Although my studio work with him was brief, we remained friends and colleagues, continuing to encourage and support each other right till the end.

Wild Things, 1997. Raku ceramic, white crackle glaze, 1/4 x 13 x 14 in.

For artists who rely on their own artistic production for survival, sculpture presents numerous challenges. Galleries have limited storage space, and collectors usually have less floor space than wall space. So Richard became inventive. He adapted. He was good at that. If you want a master class in making the most out of nothing, of indefatigable will to survive and succeed, read Richard’s memoir, Gone for the Day, and you will begin to understand.

Richard’s daughter, Michelle Pepitone, explains it this way: “I have never met anyone who loved life as much as my father. He lived life on his own terms, up until his very last breath. Bullied on the streets of Brooklyn, beaten up by his brother at home, ridiculed at school, and just feeling like he didn’t belong, he stole $150 from his parents when he was just ten years old and managed to buy a Greyhound bus ticket to Los Angeles. There he landed a job first as a dishwasher, then as a door-to-door salesman, and then worked as a day laborer. Nothing could stop him from searching for a better life. From an early age, he seemed to find pleasure in the small, daily gifts that life had to offer, and this innate gratitude seemed to stoke in him a deepening desire to live every day to the fullest no matter what the circumstances. While most people (myself included) would have been lucky to simply survive a childhood as tough as his, he thrived. In his early days growing up in Brooklyn, life seemed to deliver blow after brutal blow, but with each assault and setback, he seemed to turn the circumstances around to his advantage. The payoffs weren’t always instantaneous or even easily described, but somehow, against all odds, he would always triumph.”

Richard poured all of this resilience into making art. He rejoiced in discovery and experimentation. He would attack each new medium or method with the seriousness and focus of a laboratory scientist, noting what worked and what didn’t and always gleaning the best results. His fascination for art never waned. He excelled in whatever he tried, or maybe he somehow knew what to try to excel. He worked with plaster, polyester resin, bronze, glass, steel, wood, and found objects. He produced a significant body of ceramic artwork and dove headlong into works on paper, monotypes, collage, and relief and stencil printing. As Provincetown artist and longtime friend Salvatore Del Deo observed, he was “rather unique in the art world.… Pepitone was an artist to the very end of his fingers, to his heart. … He didn’t have to study ... or anything…. He had it already.”

Man and Woman, 1990. Bronze, 84 in. and 78 in. high. Collection of Lise Motherwell and R. S. Steinberg.

He excelled in friendship as well. He would often make a date to visit a friend, arrive with bags holding a fully prepped dinner, and cook it up right there. His homemade bread was legendary. Richard’s creativity extended to every part of his life—his food and his friends and his uniquely dapper dress were other facets of his art. He was a member of myriad circles of disparate friends—as comfortable and connected to a group of young people as to those his own age. And while the term “ladies’ man” might be a bit old-fashioned, it was definitely apropos for Richard. The women loved him. He was possibly most comfortable and at ease in their company.

He was known to be a firecracker sometimes—a hot pepper! Pepitone! Sometimes his temper would bubble over, but he was never mean-spirited. I remember he came to me once and said, “I’m going around apologizing to my friends if I ever treated them badly. How did I act with you when you worked for me?” I told him he was great. I never felt attacked or offended—ever— and it was true. I had seen it occasionally with others, but in fairness it was usually a justified reaction to some offense. But he was aware of his own nature, really valued his friendships, and probably gave away as much art as he sold.

I think his daughter Michelle’s comment sums it up well: “He was honest, sometimes brutally honest, but this lent him an authenticity rarely seen in today’s self-curated culture, and I think this is what made him so captivating and loved.”

Bill Evaul is a painter/printmaker working in Provincetown since his arrival in 1970 as a fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center. He attended Syracuse University School of Art and holds a BFA from Pratt Institute with graduate seminars at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Richard Pepitone’s work will be on exhibit Sept.15-30 locally at The Captain’s Daughters. Opening rec. Sept.15, 6-8pm.

Sorrow, 1967. Direct plaster, 10 x 16 x 24 in. A favorite piece, requested by the artist to be placed on his grave.