Replication: Influence of Context on Emotion Perception in Facial Expressions

Danica A. Barron and Ralph G. Hale* Department of Psychological Science, University of North Georgia

ABSTRACT

Accurate facial emotion perception during social interactions facilitates personal wellbeing and improves social skills such as empathy and social appraisal (Manstead et al., 1999). In the present study, we attempted to replicate this effect. Participants were presented with an image depicting a face that has been identified by Matsumoto and Ekman (1988) as a universal facial expression of “fear.” The expression is characterized by distinct features which collectively signal a state of apprehension or distress across diverse cultural contexts. Then participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 3 conditions: congruent, incongruent, or no context scenarios. The congruent context scenario suggested the face expressed fear whereas the incongruent scenario suggested the face expressed anger. Participants selected the emotion they felt was expressed by the face in the picture. We expected the congruent and nocontext groups to choose fear as the expression more often than the incongruent group. A 1way ANOVA between the 3 groups found a significant effect, F(2, 42) = 38.50, p < .001, ηp2 = .64. Congruent and no context groups chose fear as the facial expression significantly more often, thereby confirming our hypothesis and replicating previous findings. The effect of context on emotion perception is strong and replicable, suggesting that context plays an important role in emotion perception despite the universality of facial expressions.

Keywords: context, facial expression, emotion perception

The study of emotion perception, particularly in the context of facial expressions, has long intrigued researchers in the field of cognitive psychology. Building upon the seminal work in the domain, such as Carroll and Russell (1996), we sought to contribute to the understanding of how contextual cues influence the interpretation of facial expressions. Although previous literature has explored other theoretical perspectives on facial expressions and cues to emotional perception, there remains a gap in understanding the underlying processes. Although the context effect in language, visual

cognition, and processing ambiguous stimuli has provided insights into the complexities of human perception, the application of these principles in the domain of emotion perception warrants further investigation.

The process of emotion perception plays a critical role in how humans interact and communicate. Martinez (2012) suggested facial configurations are primary points of reference that aid in the interpretation of the internal status of others. The ability to accurately interpret facial expressions facilitates the understanding of the intentions and feelings. This information, however, is not perceived

Replication badge earned for transparent research practices.

in isolation and is embedded within a contextual environment that profoundly impacts its interpretation (Barrett, 2020). Evidence revealing that contextual information modulates the recognition of facial emotion provides valuable insight into social cognition, empathy, and the broad landscape of human emotional understanding.

The replication conducted in this study holds significant value in the field of emotion perception and cognitive psychology. By replication of Carroll and Russell’s (1996) work, we aimed to reinforce the reliability and generalizability of their findings in a contemporary context. Replication studies are essential for previous findings and validating theoretical frameworks. Building on the foundation laid by Carrol and Russell, we sought to extend the understanding of emotion perception through an examination of the mechanisms involved in facial expressions and their interpretation.

Facial Expressions

Facial expressions and their interpretation by others are complex. Expression involves intricately connected facial muscle movements which are unconsciously generated (Manstead et al., 1999). Darwinian perspective hypothesizes that these movements express a variety of human emotions. The behavioral ecology perspective offers a similar view, suggesting these movements are a signal instead of a direct expression of the individual’s intentions. Both theories are grounded in evolution and convey the importance of facial expression as a humanistic tool of displaying social motive and intention. The complex nature of facial expressions sets the stage for understanding the nuances involved in emotion perception, having a broader spectrum of cues and contextual influences.

Emotion Perception

To assess someone’s internal state, many cues are used including situational surroundings, body posture cues, and personal biases of the interpreter (Rajhans et al., 2016). Barrett and Bar (2009) found individual affect to be an unconscious influence on the interpretation of the emotional state of others. Barrett described this unconscious influence as an affective context effect. Previous research has demonstrated that contextual information can modulate facial emotion perception (e.g., Lee et al., 2012). Emotional information triggering advanced neural connections between amygdaloid areas and facial stimuli processing centers, such as the fusiform gyrus and superior temporal sulcus, could serve as a possible mechanism to explain this phenomenon. This enhanced connection is indicative of an evolutionary threat detection system (Mobbs et al., 2007).

The stimulus used as the facial expression for our study provided by Matsumoto and Ekman (1988) is

featured in their seminal work in facial expression research. Their study investigated the identification and interpretation of facial expressions across cultures and lays the groundwork for subsequent research in the field of emotion perception. In their examination of the six primary emotions (i.e., happiness, sadness, surprise, fear, disgust, and anger), they aimed to validate the universality of facial expressions, challenging the previous assumptions that emotional expressions were culturally determined. The Matsumoto and Ekman stimulus was comprised of carefully selected facial expressions depicting these universal emotions and has since become a cornerstone in emotion research, serving as a standard tool for investigating emotion perception, expression, and recognition across populations and contexts. Understanding emotion perception may inform how contextual factors contribute to the broad phenomenon of the context effect.

The Context Effect

The context effect is a heavily studied cognitive effect, and is a perspective that belongs to constructivist theory (Greening, 1998). This theory posits that individuals perceive reality through conceptualization of sensory stimuli, which are then used to make predictions. This conceptualization process is facilitated by top down processing and, as explained by Altman (2002), is akin to the concepts formed around phonemes that create each word (e.g., including the features and organization of letters in written speech). These topdown conceptualizations allow for the momenttomoment prediction humans use to navigate and make sense of the environment. They are learned experiences and statistical regularities, formed out of sensory information received by bottomup sensory organs that received stimulation from the environment (Panichello et al., 2013). For example, consider the human brain trying to make sense of an apple. Red light and particular line orientations reflect off the surface and reach the retina. Organic compounds reach the nose and mouth. A rounded, solid shape with specific texture and weight touches the hand that holds it. The brain combines this multimodal information into a unified interpretation that is perceived and experienced as an apple. Ngo (2015) highlighted that the unification of this sensory information may be a relatively quick process for familiar stimuli, or a slow process for more ambiguous stimuli.

In exploring the context effect, it becomes evident that semantic context plays a crucial role in shaping perceptions and interpretations of emotional stimuli. This is especially true because the semantic context effect encompasses the influence of linguistic and conceptual information on the emotion being perceived. This influence emerges as a central focus of our investigation. As individuals navigate social

interactions, the semantic context surrounding these expressions serves as a powerful cue, guiding the understanding of the other’s emotional state. We hypothesized that semantic context would significantly modulate the interpretation of facial expressions, ultimately shaping an emotional understanding and response. The significance of the context effect is influenced by adaptation to a stimulus, priming effects, and cues. Adaptation to a stimulus refers to the process of sensory systems adjusting to sensory information over time. The more a person encounters a stimulus, the less sensitive and responsive they become to it. This plays a crucial role in how context can elicit differences in perception by shifting focus from repetitive stimuli to detecting changes in the environment (Werner et al., 2005). Priming cues are the exposure to a stimulus that influences the processing of other, later information in the environment. This phenomenon may impact aspects of perception, memory, and decisionmaking. Cues trigger mental associations or concepts that allow memory to interact with perception (Schacter et al., 2004). For example, exposure to an advertisement about a nearby beach may impact the processing of later beachrelated stimuli. The interaction between environmental cues and cognitive processing becomes particularly evident in the perception of ambiguous stimuli.

Ambiguous Stimuli

Ambiguous stimuli are subject to perceptual cycling and mutual exclusivity. Perceptual cycling describes the patterned saccadic eye movements that alternate between two perceptual sets or representations of the brain’s prediction for the sensory information being received from the environment (VanRullen, 2016). Mutual exclusivity is a phenomenon in which sensory information offers conflicting evidence of the representation, thus affecting the stability of the interpretation (Klink et al., 2012). These two distinct features are characteristic of ambiguous stimuli. For example, the Necker cube is a twodimensional representation of a cube that appears as a three dimensional cube in one of two configurations (i.e., pointing up and to the left or pointing down and to the right). Context (e.g., past experience with depth perception, typical view angles for cubes, practice with Necker cubes) can help disambiguate the orientation; however, observers are typically still able to switch orientations exogenously or endogenously by intentionally switching the orientation or allowing for incidental orientation shifts, respectively. The complexities inherent in interpreting ambiguous stimuli parallel the contextual influences that shape the perception of ambiguous emotional stimuli.

Ambiguous Emotion Perception

Emotion perception allows the same ambiguity criteria. As mentioned before, every emotional expression is not completely diagnostic of the internal state of another. Facial expressions or emotional cues are unclear and open to multiple interpretations. Mixed or dimorphous expressions may further complicate perception. Dimorphous expressions result from a combination of elements from two conflicting emotions (Aragón, 2017). For example, when someone experiences intense joy and starts to cry, they are exhibiting a dimorphous expression. There are additional reasons why emotion perception may be ambiguous, including subtle expressions, cultural differences, individual differences, and contextual influences (Biehl et al., 1997; Martin et al.,1996). These contextual ambiguities may elicit negative social outcomes (e.g., miscommunications, misunderstandings, and difficulties empathizing). Additionally, this effect has been shown to be heightened for those diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Stagg (2021) suggested that ASD may be reflective of the difficulty of retrieving and utilizing previously learned concepts and applying them to present perceptions. This may indicate a conceptual network problem for individuals with ASD. Building on the challenges posed by ambiguous emotion perception, the we sought to dive deeper into the interaction between semantic context and facial expression perception.

The Present Study

This replication study delved into the fascinating interplay between semantic context and facial emotion perception. The present study was identical to the original study by Carroll and Russell (1996), including stimuli, measures, manipulation, and analysis procedures. We hypothesized there would be a significant influence of semantics, including the meaning derived from the facial expression and the context provided via written scenarios, on facial expression perception.

Method

Participants

A total of 45 participants completed our study. Participants were recruited from the university’s Electronic Sona/NERD research participant pool. A power analysis conducted using G*Power version 3.1.9.4 (Faul et al., 2007) to determine the required sample size for our one way ANOVA between subjects design. We aimed for a significance level (α) of .05, a desired power of .80, and assumed a large effect size based on previous literature (ηp2 ≥ .14). A large effect was assumed based on previous research into this phenomenon (e.g., ηp2 = .30 in Barrett & Kensinger, 2010, and ηp2 = .33 in

WINTER 2024

Ngo & Isaacowitz, 2015). The power analysis indicated that a minimum sample size of 42 to 66 participants was needed to detect the anticipated effects. All participants were at least 18 years of age or older at the time of participation and provided informed consent before participating. Demographic data—including gender, race, and ethnicity—was not collected. We recognize this is a limitation of this study, and future research will include demographic measurements to promote equity and representation in research (see Roberts et al., 2020). Participants were granted partial course credit as compensation for their participation. This study adhered to the ethical standards and practices outlined by the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures

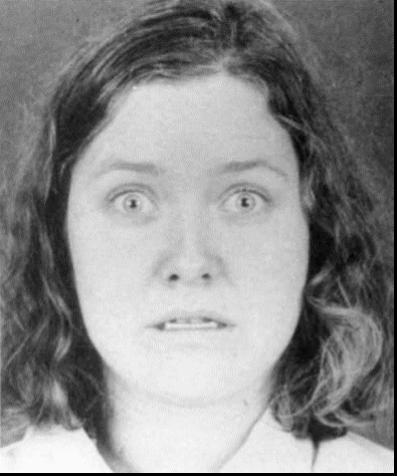

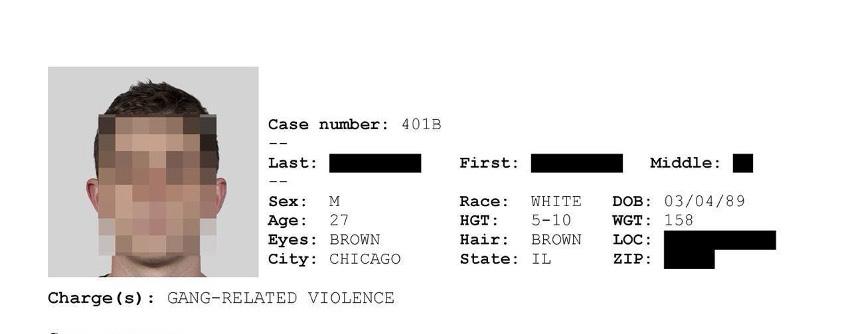

The study was created using Qualtrics and was administered to participants online through this platform. The Qualtrics study included the consent form, instructions, experiment, and debrief. For the experiment, a single stimulus was used (see Figure 1). The facial expression stimulus was identical to the stimulus used by Matsumoto and Ekman (1988) and Carroll and Russell (1996). The image is a headshot of a woman exhibiting the universal facial expression for fear, as detailed by Tomkins (1992). There were three between subjects conditions in this study: no scenario (n = 15), congruent scenario (n = 15), and incongruent scenario (n = 15). The congruent and incongruent scenarios are identical to those used in Carroll and Russell (1996). See Table 1 to read these scenarios. The congruent scenario suggests the correct interpretation of the facial expression should be fear, whereas the incongruent scenario suggests anger is the correct interpretation of the stimulus.

The emotion selection measure was a fouralternative forced choice response. For the noscenario and congruent scenario conditions, the response items included fear, anger, excitement, and disgust. In the incongruent scenario condition, excitement was replaced with sadness; all others were the same.1 Response items were simplified from the item sets used by Carroll and Russell (1996). The original study also tested for situational dominance unlike the present study; therefore, fewer response items were required here. The simplified set of response items used in the present study was used in the original study. These response items are also consistent with Imbir (2017)

1As a replication study, we used response items from the original set of items in Carroll & Russell (1996). However, future research should use a list of common response items between all groups to avoid design confounds. It is worth noting that no participants selected “excitement” or “sadness” in this experiment, the only two items that differ between conditions.

eight sectors of primary emotions. This model categorizes each emotion, providing a detailed representation of distinct facets of human emotional experience and an overview of the emotional spectrum. This model also provides researchers with a structured framework for understanding and classifying emotional responses. For congruent and incongruent conditions, response items were randomized between participants to avoid order effects. Barron and

Facial Expression Stimulus

Note. This facial expression is commonly associated with fear (Tompkins, 1992; Biehl et al., 1997). However, it can become ambiguous with the addition of scenario-based context. This image is reproduced with permission from Matsumoto and Ekman (1988).

TABLE 1

Congruent Versus Incongruent Scenarios

From Carroll & Russell, 1996

Congruent context scenario

“This is a story about a woman who had never done anything really exciting in her life. One day she decided she had to do something exciting, so she enrolled in a class for parachuting. Today is the day that she will make her first jump. She and her class are seated in the plane as it reaches the right altitude for parachute jumping. The instructor calls her name. It is her turn to jump. She refuses to leave her seat.”

Incongruent context scenario

“This is a story of a woman who wanted to treat her sister to the most expensive, exclusive restaurant in their city. Months ahead, she made a reservation. When she and her sister arrived at the restaurant, they were told by the host that their table would be ready in 45 minutes. Still, an hour passed, and no table. Other groups arrived and were seated after a short wait. The woman went to the host and reminded him of her reservation. He said he would do his best. Ten minutes later, a local celebrity and his date arrived and were immediately shown a table. Another couple arrived and were seated immediately. The woman again went to the host, who said that all the tables were now full, and that it might be another hour before anything was available.”

FIGURE 1

Procedure

To begin this experiment, participants provided informed consent via Qualtrics. Then age data was collected to confirm they were at least 18 years old. Participants were then randomly assigned to one of three conditions: no scenario, congruent scenario, and incongruent scenario. Following randomization, all participants received instructions for the experiment. The instructions stated they would be shown an image and be asked to make a judgement based on this image. The two scenario groups (congruent and incongruent) also received instructions stating they would read a scenario

to help them make their judgement. Participants confirmed they had read the instructions. Then all groups were shown the face stimulus (see Figure 1). The scenario groups were also shown their scenario. The scenario and face were present simultaneously for these two groups. Participants had an unlimited amount of time to make their judgement. The judgement item asked, “What is the woman feeling?” To respond, participants selected one of four emotions from a dropdown menu. Only a single trial was conducted. Then, participants read a debriefing script which explained the purpose of the study and provided them with researcher contact information in case they had any questions.

Results

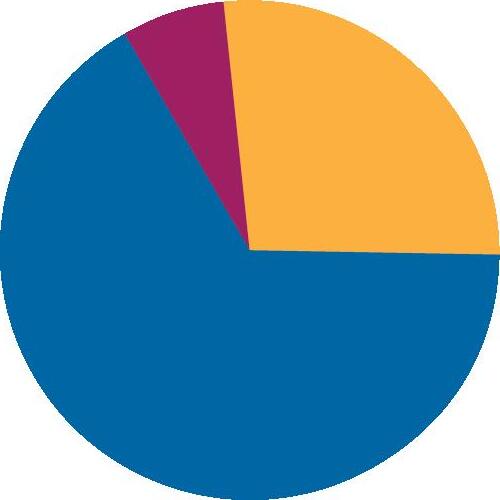

A one way ANOVA found a significant effect of Condition, F (2, 42) = 38.50, p < .001, η p 2 = .64. All participants in the no scenario ( M = 1.0, SD = 0.0) and congruent scenario (M = 1.0, SD = 0.0) conditions selected fear as the emotion expressed. However, only 23.5% of the incongruent group (M = 0.24, SD = 0.29) selected fear (see Figure 2). Pairwise comparisons found both noscenario and congruent scenario to be significantly different from incongruent scenario, ps < .001. These findings suggest that contextual cues significantly influenced participants interpretation of facial expressions, supporting the hypothesis of contextual biasing on emotion perception. The effect size, which falls into the range of large significance, indicates a substantial impact of the experimental manipulation on participant responses.

Discussion

Distribution of Accuracy

Note.

The purpose of this study was to establish the replicability of contextual biasing on facial expression perception. We conducted a simplified replication of Carroll and Russell’s (1996) study, in which a face showing a universal expression of fear was presented to participants accompanied with no context, congruent context, or incongruent context depending on condition. The context effectively primed participants to adjust their expectations—and therefore their perceptions—for the emotion portrayed in the facial expression. This suggests that the mechanisms responsible for correctly interpreting emotions from facial expressions relies not only on characteristics and patterns of facial features, but also on situational factors leading up to the generation of a particular facial expression. These situational factors were provided in the form of scenarios.

The congruent scenario primed participants to believe the person pictured was afraid. This matched the universal facial expression portrayed in the photograph. However, the incongruent scenario primed

FIGURE 3

FIGURE 2

Facial Expression Stimulus

Note. For the three conditions (no-context, congruent, and incongruent) of this experiment, the percentage of fear responses are shown. For the incongruent condition, most participants did not select fear. See Figure 3 for breakdown of incongruent participant responses.

participants to believe the person pictured was angry. As seen in Figures 2 and 3, this context and priming was effective. Despite the face exhibiting the universal expression for fear, only 4 out of 15 participants (26.67%) in the incongruent condition rated the expression as fear. This is compared to 10 out of 15 participants (66.67%) rating the expression as anger. Alternative explanations to these results may include attention and demand characteristics. Participants’ individual differences in attentional capacity, cognitive biases, or momentary distractions may have influences responses. For instance, participants who were more attentive or had a heightened sensitivity to facial cues might have been more inclined to accurately perceive the emotions. Furthermore, demand characteristics, which refer to the participants’ tendency to alter their behavior or responses based on the perceptions of others, should also be considered. Even though the participants were unaware of the specific hypotheses, they might have unconsciously adjusted their responses to align with perceived expectations or to comply with what they believed researchers wanted to observe. Although their lack of awareness reduces the likelihood of these variations, subtle influences on attention and behavior cannot entirely be ruled out. These findings replicate findings from the previous work of Carroll and Russell (1996), suggesting that facial expression emotion perception is more complex than simply interpreting universal facial expressions based on facial features alone.

Applications

As context is naturally elucidating, it makes sense that it would significantly influence how individuals interpret facial emotion cues. This holds implications beyond the scope of the present study. Bottomup input is rarely processed in isolation without influence from topdown information, and the perceptual processing system develops to establish which aspects of stimuli are most important for focusing selective attention (Barrett, 2020).

The significance of the context effect can be applied to many social interactions (Manstead et al.,1999). Heightened awareness of the interplay between context and socializing could enhance effective communication. For instance, teaching individuals to recognize and consider context when interpreting facial expressions might help them navigate interpersonal relationships more effectively, thereby demonstrating a potential benefit from the implementation of socialemotional learning in childhood education (West & Turner, 2011). The connection between context and emotion perception could also guide the development of artificial intelligence systems, leading them to better mimic human emotional

understanding (Shin, 2021). Additionally, these connections may be useful in clinical settings to treat conditions such as social anxiety and autism spectrum disorder (Stagg et al., 2021). Further, accurate perception of emotions can benefit law enforcement and security personnel in assessing individuals’ emotional states accurately in interviews, interrogations, and airport security checks (Barrett et al., 2011). Together, it is clear the applications of context and facial expression perception interactions are ubiquitous and impactful.

Future Directions

The present study was limited in its scope and design due to a few factors. Importantly, the data was collected online with limited control of participant experience. For instance, we could control what is displayed on Qualtrics, but we could not ensure proper eye gaze or attention during instructions, stimulus presentation, or scenarios. We did replicate previous findings; however, future research should be conducted in person to increase internal validity of the study.

Additionally, this study could be expanded in terms of sample size and sample diversity. A larger, more diverse sample size could improve generalizability beyond a college student population. As mentioned previously, collecting demographic data—including race, ethnicity, and gender—would be useful in determining whether this effect is variable between demographic factors. If not, it would speak to the universality of the impact of context on facial expression perception. This would be significant to establish as the universality of facial expression perception without context has already been established, as described previously.

The design could also be expanded to include a larger variety of faces and expressions. The present study was a simplified replication. However, the original study could be expanded further to include a range of faces from various races, ethnicities, genders, and ages; a wider range of universal facial expressions could be used; and more variety could be included in the scenarios leading to the congruent and incongruent conditions. This increased design variety would provide a more nuanced understanding of the interplay between context and expression perception.

The present study only utilized vision to examine the connection between context and emotion perception. However, future research could investigate the use of context on emotion perception using other sensory systems such as audition. For instance, a scream may be a universal cue for fear, but context could indicate elation. Perhaps other sensory systems could be explored as well. Looking further into the crossmodal effect of context may better inform how this effect impacts

emotion perception abstractly as a global mechanism. Interestingly, this could be explored for typically developing populations and those with neurological developmental delays and disorders as well.

References

Altmann, G. M. (2002). An interactive activation Model of context effects letter perception. In Psycholinguistics: Critical concepts in psychology (pp. 422–450). Routledge.

Aragón, O. R. (2017). “Tears of joy” and “Tears and joy?” personal accounts of dimorphous and mixed expressions of emotion. Motivation and Emotion, 41(3), 370–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-017-9606-x

Barret, L. F. (2020). How emotions are made: The secret life of the brain. Picador. Barrett, L. F., & Bar, M. (2009). See it with feeling: Affective predictions during Object Perception. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1521), 1325–1334. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2008.0312

Barrett, L. F., & Kensinger, E. A. (2010). Context is routinely encoded during emotion perception. Psychological Science, 21(4), 595–599. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610363547

Barrett, L. F., Mesquita, B., & Gendron, M. (2011). Context in emotion perception. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(5), 286–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411422522

Biehl, M., Matsumoto, D., Ekman, P., Hearn, V., Heider, K., Kudoh, T., & Ton, V. (1997). Matsumoto and Ekman’s Japanese and Caucasian facial expressions of emotion (JACFEE): Reliability data and cross-national differences. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 21(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1024902500935

Carroll, J., & Russell, J. (1996). Do facial expressions signal specific emotions? Judging emotion from the face in context. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(2), 205–218. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.2.205

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03193146

Greening, T. (1998). Building the constructivist toolbox: An exploration of cognitive technologies. Educational Technology, 38(2), 22–35. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44428434

Imbir, K. K. (2017). Psychoevolutionary theory of emotion (Plutchik). Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_547-1

Klink, P. C., Van Wezel, R. J., & van Ee, R. (2012). United we sense, divided we fail: Context-driven perception of ambiguous visual stimuli. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 367(1591), 932–941. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2011.0358

Lee, T.-H., Choi, J.-S., & Cho, Y. S. (2012). Context modulation of facial emotion perception differed by individual difference. PLoS ONE, 7(3). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0032987

sensitivity. Journal of Research in Personality, 30(2), 290–305. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1996.0019

Martínez, A. M., & Du, S. (2012). A model of the perception of facial expressions of emotion by humans: Research overview and perspectives. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 13, 1589–1608.

Matsumoto, D., & Ekman, P. (1988). Japanese and Caucasian facial expressions of emotion (JACFEE). Unpublished slide set and brochure, Department of Psychology, San Francisco State University.

Mobbs, D., Petrovic, P., Marchant, J. L., Hassabis, D., Weiskopf, N., Seymour, B., Dolan, R. J., & Frith, C. D. (2007). When fear is near: Threat imminence elicits prefrontal-periaqueductal gray shifts in humans. Science, 317(5841), 1079–1083. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1144298

Ngo, N., & Isaacowitz, D. M. (2015). Use of context in emotion perception: The role of top-down control, cue type, and perceiver’s age. Emotion, 15(3), 292–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000062

Panichello, M. F., Cheung, O. S., & Bar, M. (2013). Predictive feedback and conscious visual experience. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00620

Rajhans, P., Jessen, S., Missana, M., & Grossmann, T. (2016). Putting the face in context: Body expressions impact facial emotion processing in human infants. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 19, 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2016.01.004

Roberts, S. O., Bareket-Shavit, C., Dollins, F. A., Goldie, P. D., & Mortenson, E. (2020). Racial inequality in psychological research: Trends of the past and recommendations for the future. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(6), 1295–1309. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620927709

Schacter, D., Dobbins, I. & Schnyer, D. Specificity of priming: A cognitive neuroscience perspective. Nature Review Neuroscience 5, 853–862 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1534

Shin, D. (2021). The perception of humanness in Conversational journalism: An algorithmic information-processing perspective. New Media & Society, 24(12), 2680–2704. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444821993801

Stagg, S., Tan, L.-H., & Kodakkadan, F. (2021). Emotion recognition and context in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 52(9), 4129–4137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-021-05292-2

Tomkins, S. S. (1992). Affect, imagery, consciousness (Vol. 1–2). Springer. Webster, M. A. VanRullen, R. (2016, August 23). Perceptual cycles. Trends in Cognitive Sciences https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364661316301048

Werner, J. S., & Field, D. J. (2005). Adaptation and the phenomenology of perception. Fitting the Mind to the World Adaptation and After-Effects in High-Level Vision, 241–278. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198529699.003.0010

West, R. L., & Turner, L. H. (2011). Understanding interpersonal communication: Making choices in changing times. Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

Author Note

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Ralph G. Hale, University of North Georgia, 3820 Mundy Mill Rd, Oakwood, GA 30566. Email: ralph.hale@ung.edu Influence

Manstead, A. S. R., Fischer, A. H., & Jakobs, E. B. (1999). The social and emotional functions of facial displays. In P. Philippot, R. S. Feldman, & E. J. Coats (Eds.), The social context of nonverbal behavior (pp. 287–313). Cambridge University Press; Editions de la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme. Martin, R. A., Berry, G. E., Dobranski, T., Horne, M., & Dodgson, P. G. (1996). Emotion perception threshold: Individual differences in emotional

Ralph G. Hale https://orcid.org/0000000150268417

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose. Many thanks to Anna Adamo, Pilar AmbrizCalleros, and Kimberly Carpenter for their creative input and contributions to this project.

The Interplay of Depression, Rumination, and Negative Autobiographical Memory

Patricia M. Roberts and Jason R. Finley* Department of Psychology, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville

ABSTRACT. This experiment investigated rumination as a possible mechanism for the phenomenon of depression increasing negative autobiographical memories. Participants recalled a negative autobiographical memory involving school before rating the negative mood intensity of that memory, then half of the participants ruminated on that memory and half of the participants were distracted from it. Participants then rated the memory again, and either ruminated or were distracted for a second time before rating the memory for a third time and completing the Beck Depression InventoryII, the Rumination on Sadness Scale, and demographic questions. The negative mood intensity of the autobiographical memory decreased over time, but did so to a lesser extent when participants ruminated on it versus being distracted (interaction p < .001, d = 1.01). Furthermore, for the rumination condition, participants with greater depression scores reported negativity ratings that decreased at a slower rate over time; for the distraction condition, participants with greater depression scores reported negativity ratings that decreased at a faster rate over time (interaction p = .040, ∆R2 = .047). Depression leads to rumination, and may also amplify the effect of rumination on the negativity of autobiographical memories. The effects of rumination may be due to memory effects such as retrieval practice and mood congruency. Individuals experiencing higher levels of depressive symptom severity may be more likely to experience increasingly negative memories due to rumination.

Keywords: depression, rumination, autobiographical memory, mood congruency, negative mood intensity

Depression is a general negative affective state in which individuals can experience symptoms of unhappiness, lack of motivation, and changes in habits regarding social connections, eating, and sleeping (American Psychological Association [APA], n.d.a) Autobiographical memory includes an individual’s memory for events that they have experienced (APA, n.d.b). Depression influences autobiographical memory by biasing recall to negative events (Hitchcock et al.,

2020; Lyubomirsky & NolenHoeksema, 1995; Peeters et al., 2003; Vrijsen et al., 2001). One potential mechanism by which depression may have this effect is through rumination, which is when an individual repeatedly has similar thoughts to the point of interference with other mental activities (APA, n.d.c). Thus, for the current study, we investigated the interplay between depression, rumination, and autobiographical memory.

PSI

Depression and Autobiographical Memory

Research has shown a negativity bias in memory for simple materials in people with depression. For example, results from a study by Bianchi et al. (2020) found that a group of participants who scored low on a selfreport depression scale recalled more positive words and fewer negative words compared to a group of participants who scored high on the scale, with the latter group recalling fewer positive words and more negative words. The results were based on responses from 1,015 participants who completed a free recall task involving 10 positive and 10 negative words. It is possible that a negativity bias also extends to memories from everyday life.

There are a number of ways to investigate depression’s effects on autobiographical memory. Simply having participants attempt to recall good and bad days is one approach. For example, when participants were asked to remember both positive and negative events from their lives, Hitchcock et al. (2020) found that healthy control participants (who had never been depressed) recalled significantly more positive memories than negative memories. This was in contrast to participants with depression, for whom there was no significant difference in the number of positive memories and negative memories recalled. However, results also showed that participants with depression rated their memories less positively compared to healthy control participants.

Another approach is to use experience sampling to form records of participants’ experiences. For example, Peeters et al. (2003) conducted a study in which participants filled out self report forms reporting their current mood, negative and positive events, and appraisals of the events 10 times a day for six days. Results showed that participants with depression reported fewer positive than negative events and reported negative events as more unpleasant compared to participants without depression. Results also showed that overall, participants with depression had higher base levels of negative mood for memories compared to participants without depression, and this was particularly true for participants with more severe depression and/or who had a longer duration of depression. Studies using experience sampling have also shown that people with depression are biased to recall more negative experiences than they actually had. Urban et al. (2018) conducted a study in which 1,657 participants made daily records of emotional experiences for eight days in a row, and recalled those experiences at the end of the final day. Results showed that participants with a history of depression particularly overestimated how often they had experienced negative emotions, consistent with a negative memory bias due to depression.

Depression and Rumination

One hallmark of depression is the tendency toward repetitive thoughts, known as rumination. A variety of studies have shown such a relationship (Mitchell, 2016). For example, Harrington and Blankenship (2002) found a medium correlation of r = .33 between rumination and depression with 199 participants. NolenHoeksema (2000) interviewed 1,132 participants on two occasions, one year apart, and found that participants with depression at Time 1 experienced greater levels of rumination at Time 1 and Time 2 compared to participants without depression. Additionally, results showed that rumination at Time 1 predicted diagnostic status for depression at Time 2. The relationship between rumination and depression is further evidenced by studies that experimentally manipulate rumination. For example, Lyubomirsky and NolenHoeksema (1995) found that inducing rumination in participants with dysphoria led them to have more negative interpretations of hypothetical situations as compared to participants with dysphoria who were not induced to ruminate.

Rumination as a Mechanism Linking Depression and Negative Memories

Some studies have suggested rumination as a possible reason for depression increasing a bias towards negative memories. Research by Lyubomirsky et al. (1998) experimentally investigated the effects of distraction compared to rumination on mood and autobiographical memory in participants with and without depression. In Experiment 1, there were 72 participants who either ruminated or were distracted before recalling personal memories and rating the emotional valence of those memories. Results showed that depressed participants who ruminated became more depressed, but depressed participants who were distracted became less depressed; there was no significant difference in nondepressed participants who ruminated or were distracted. Additionally, results showed that depressed participants who ruminated rated their autobiographical memories as more negative and less positive than any other group. Park et al. (2004) found similar results with adolescents, showing that there was a greater increase in depressed mood with rumination than distraction for adolescents with depression compared to adolescents without depression.

Current Study

In summary, previous research has suggested that there is a relationship between depression and rumination such that rumination causes an increase in negative mood (Lyubomirsky et al., 1998; Lyubomirsky & NolenHoeksema, 1995; Park et al., 2004). The current

WINTER 2024

experiment sought to further explore such a relationship by measuring the effects of rumination and distraction at multiple timepoints, before and after more than one round of distraction or rumination, thus investigating how rumination changes the emotional context of an autobiographical memory, with depressive symptom severity as a moderator and general rumination tendency as a covariate.

Participants described a negative past event involving school and rated the emotional intensity of the memory three times (Time 1, Time 2, and Time 3). Half of the participants were induced to ruminate about the memory for 3 min between ratings, and the other half were distracted for 3 min between ratings. Finally, participants completed the Beck Depression InventoryII (Beck et al., 1996), the Rumination on Sadness Scale (Conway et al., 2000), and demographic questions.

We investigated three hypotheses. The first hypothesis was that there would be a twoway interaction between time and task such that by distracting from a negative autobiographical memory, the negative mood intensity of the memory would stay the same across Times 1, 2, and 3. In contrast, by ruminating on a negative autobiographical memory, the negative emotional intensity of the memory would increase across Times 1, 2, and 3. This prediction can be seen in Figure 1.

The second hypothesis was that there would be a three way interaction between time, task, and depression such that participants with greater levels of depressive symptom severity in the rumination condition would have a greater increase in negative mood intensity across time compared to participants with lower levels of depressive symptom severity in the rumination condition. That is, depression would amplify the negative effect of rumination.

The third hypothesis was that there would be a main effect of depression so that, even at Time 1, participants with greater depressive symptom severity would have higher ratings of negative mood intensity for their memory.

Method

Participants

Participants were 73 students in the introductory psychology course at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville who participated for partial fulfilment of a course requirement in February 2022. Participants completed the study online via Qualtrics, and gave consent to participate by checking a box. Data were additionally collected from 10 other participants but were excluded from analysis due to incomplete data. The mean age of the participants was 19.49 (SD = 2.06, range = 18–31), with one participant not reporting their

age. There were 61 women and 12 men. With sample size N = 73 the study obtained 80% power to detect effect sizes of size d = 0.66 or greater for betweensubjects t tests, and r = .32 or greater for correlations. This study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board of Southern Illinois University Edwardsville (Protocol #1488).

Design

The independent variables were time (Time 1, Time 2, and Time 3; withinsubjects) and task (distraction vs. rumination; betweensubjects). Participants were randomly assigned to either the distraction group ( n = 36) or rumination group (n = 37). The main dependent variable was the negative mood intensity for the autobiographical memory and was measured using a sliding scale with values ranging from 0–100 (0 = extremely positive, 100 = extremely negative), where higher numbers corresponded with a higher negative mood intensity. In addition, depressive symptom severity was measured as a quasiindependent variable using the Beck Depression InventoryII, and rumination frequency was measured as a potential covariate using the Rumination on Sadness Scale.

Materials

The Beck Depression InventoryII (Beck et al., 1996) is a 21item, selfreport questionnaire that was used to measure the level of participants’ depressive symptoms from within the past 2 weeks. Questions use a 4point scale, with higher values indicating greater symptom severity. Across many studies, the BDI II has been found to have high internal consistency, with a mean Cronbach’s alpha of .90 (Wang & Gorenstein, 2013). In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was .93.

The Rumination on Sadness Scale (Conway et al.,

Note. Time periods were 3 minutes apart.

FIGURE 1

Prediction of Hypothesis 1

2000) is a 13item, selfreport questionnaire that was used to measure the extent to which participants ruminate on sad memories in general. Questions use a 5point scale (1 = not at all, 5 = very much), with higher values indicating greater rumination. Conway et al. (2000) reported a Cronbach’s alpha of .91. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha was .93.

For both the Beck Depression InventoryII and the Rumination on Sadness Scale, we calculated each participant’s score as the mean of their responses on the questions for each scale. This was done instead of summation in order to allow for missing values.

Procedure

The experiment was completed online using the Qualtrics website after participants signed up on the Sona participant pool website. Participants were first told to describe a single clear and specific negative experience involving school, which they typed in a freeresponse textbox. They then reported how long ago the experience occurred, and rated the negative mood intensity of the experience using a sliding scale from 0 (extremely positive) to 100 (extremely negative). Participants could view the value for their rating when moving the slider. After initially describing the experience, participants were randomly assigned to either think about that negative experience for 3 minutes (rumination condition), or to think about the external stimuli of clouds forming in the sky for 3 minutes (distraction condition).1 Next, participants again rated the negative mood intensity of their past experience on a 0–100 sliding scale for a second time. Then, participants in the rumination group again ruminated on the experience for 3 minutes and participants in the distraction group again focused on the external stimuli of clouds forming in the sky for 3 minutes. The participants then rated the negative mood intensity of their past experience on a 0–100 sliding scale for a third time. Finally, all participants completed the Beck Depression InventoryII, the Rumination on Sadness Scale, and demographic questions (age and

1

distraction condition was derived from Lyubomirsky et al. (1998).

gender). As part of debriefing, participants were given a link to free counseling services at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville. See Figure 2 for a diagram of the procedure. Complete instructions are included at https://osf.io/h657r

Results

Both the Beck Depression Inventory II and the Rumination on Sadness Scale showed high reliability as measured by Cronbach’s alpha (.93 for both). Participant scores on both scales were calculated as the mean of their responses to all items. The obtained range for the Beck Depression InventoryII score was 1–3.24 (M = 1.78, SD = 0.55) with the total possible range being 1–4. The obtained range for Rumination on Sadness Scale score was 1–4.85 (M = 2.71, SD = 0.93) with the total possible range being 1–5. Data are available at https://osf.io/h657r

Hypothesis 1: Rumination Will Increase the Negative Mood

Intensity

Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations of the negativity ratings across time periods, separately for the distraction and rumination conditions. The skewness of the distributions for these ratings were 0.36, 0.10, and 0.65 for the distraction condition, and 1.29, 0.69, and 0.85 for the rumination condition, for Time 1, Time 2, and Time 3 respectively. As illustrated in Figure 3, negativity ratings appeared to decrease over time for both conditions. In order to analyze these decreases, we calculated a simple linear regression slope across Times 1–3 for each participant. 2 These slopes were used for all subsequent analyses, because the change in negativity rating over time was of key interest. Twotailed singlesample t tests compared the mean

2For example, one participant’s three negativity ratings were 76, 51, and 37. A simple linear regression for that participant yields a slope of -19.5. This slope gives a single number representing the overall change in rating across the three time periods for this participant. Having such a single score for each participant simplifies analyses, for example allowing a comparison of mean slopes across conditions using a t test, rather than requiring a 2-way ANOVA.

WINTER 2024

The task for the

FIGURE 2

Diagram Outlining the Basic Procedure

slopes of the distraction and rumination conditions to zero. For the distraction condition the mean slope was 17.07 (SD = 11.67), t(35) = 8.65, p < .001, d = 1.46. For the rumination condition the mean slope was 5.08 (SD = 11.77), t(36) = 2.59, p = .014, d = 0.43. Thus, in both conditions, negativity ratings statistically significantly decreased over time. The singlesample t tests were followed by a twotailed betweensubjects t test comparing the mean slopes between the distraction and rumination conditions (i.e., looking for a 2way interaction between time and task). The mean slope was indeed significantly different in the two conditions such that the negative mood intensity decreased more in the distraction condition than the rumination condition, t(71) = 4.31, p < .001, d = 1.01.

Hypothesis 2: Depression

Will Amplify the Effect of Rumination

First, we analyzed the overall relationship between depressive symptom severity and the negative mood intensity over time (i.e., the slope) and no correlation was found, r(71) = .03, p = .807, suggesting no overall relationship between depressive symptom severity and change in negativity rating. However, when we analyzed this correlation separately for the two conditions, an interesting pattern emerged. For the distraction condition, there was a negative correlation between depressive symptom severity and slope, r(34) = .20, p = .255; for the rumination condition, there was a positive correlation between depressive symptom severity and slope, r(35) = .29, p = .080. Although neither was statistically significant with our sample size, these smalltomedium sized correlations were in the opposite direction, suggesting that the relationship between depressive symptom severity and negativity rating over time depended on the condition (distraction vs. rumination). Thus, we next analyzed depressive symptom severity as a potential moderator using a multiple linear regression to determine if there was an interaction between the effect of depressive symptom severity and condition on negative mood intensity over time. Results of this regression are shown in Table 2, and the interaction was indeed significant. To better understand this interaction, we created a scatterplot, shown in Figure 4. The yaxis shows the direction and extent to which negativity ratings changed over time for a given participant (i.e., the participant’s slope). For the distraction condition, the higher a participant’s depressive symptom severity, the more negative their slope was (i.e., their negativity ratings decreased over time to a greater extent). For the rumination condition, the higher a participant’s depressive symptom severity, the less negative their slope was (i.e., their negativity ratings decreased over time to

a lesser extent). Simple linear regression equations for both conditions are shown in Figure 4. Although we had originally predicted that negativity ratings would increase over time in the rumination condition, in fact the ratings decreased over time for the majority of participants in both conditions. However, as seen in Figure 4, the negativity rating did increase over time for 12 participants as seen by the dots above zero

TABLE 1

Mean (SD) of Negativity Ratings by Condition and Time

Note. Ratings were made on a 0–100 sliding scale, where 0 was extremely positive and 100 was extremely negative. Time periods were 3 minutes apart.

TABLE 2

Regression of Condition on Negativity Rating Over Time With Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI) as Moderator

Note. Outcome variable is slope of negativity rating across Times 1–3; Condition = distraction (0) vs. rumination (1); BDI = Beck Depression Inventory-II. Overall R2 = .256.

Mean Negativity Ratings by Condition and Time

Note. Error bars represent standard errors. Time periods were 3 minutes apart.

FIGURE 3

on the yaxis. Interestingly, 11 of these 12 cases were in the rumination condition. A sign test verified that this is a significant difference, z = 2.73, p = .006. These results of the sign test allude to the original hypothesis, but do not fully support it.

The Rumination on Sadness Scale was measured to see how much a participant tends to ruminate on their own. This could contribute to how the rumination manipulation affects participants, and thus be

TABLE 3

Regression of Condition on Negativity Rating Over Time With Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI) as Moderator and Rumination on Sadness Scale (RSS) as Covariate

an additional source of variance. So, we included Rumination on Sadness Scale in an additional regression in order to see if the relationship between task, depressive symptom severity, and negativity rating over time could be clarified when variance due to rumination was explicitly modeled. The results of this regression are shown in Table 3. The regression did not provide any additional insights. A possible reason for this is that the Beck Depression InventoryII and Rumination on Sadness Scale are similar in what they measure; Conway et al. (2009) reported r(211) = .56, p < .001. This shows a large positive correlation between rumination and depressive symptom severity, which is replicated in the current study, r(71) = .68, p < .001.

Hypothesis 3: High Depression Levels Will Correlate With High Negativity Ratings

at Time 1

Finally, to test the third hypothesis, we calculated a correlation between depressive symptom severity and negativity rating at Time 1 and found that it was small and positive but not significant r(71) = .18, p = .136. Thus, there was no statistically significant difference in the initial negativity of the autobiographical memory as a function of depressive symptom severity.

Note. Outcome variable is slope of negativity rating across Times 1–3; Condition = distraction (0) vs. rumination (1); BDI = Beck Depression Inventory-II; Interaction is between Condition and Beck Depression Inventory-II Score; RSS = Rumination on Sadness Scale. Overall R2 = .267.

FIGURE 4

Scatterplot of Negativity Rating Over Time and Beck Depression Inventory-II Score by Condition

Note. Slope of zero (horizontal line) indicates no change in negativity rating over time.

Discussion

Results showed that negative mood intensity ratings of an autobiographical memory decreased across time when participants repeatedly ruminated about the memory and when they were repeatedly distracted. This pattern (see Figure 3) differed from our first hypothesis that negative ratings would increase with rumination and stay the same with distraction (see Figure 1). However, the difference in the effects of the distraction condition compared to the rumination condition was statistically significant, so that the negative memory was viewed less negatively over time for the distraction condition than the rumination condition. That is, the relative difference in the slopes was as we predicted, but the absolute direction of the slopes was not.

The results were somewhat consistent with our second hypothesis that there would be an interaction between depression, time, and task. We did find a threeway interaction (see Figure 4). However, rather than our prediction that participants with a greater level of depression would show a greater increase in negative ratings of their memory across repeated ruminations, they instead showed a diminished decrease relative to less depressed participants. Furthermore, participants with a greater level of depression in the distraction condition showed a greater decrease in negative ratings of their memory across time relative to less depressed participants. Overall, 11 of the 12 participants who showed an increase

in negative mood intensity were in the rumination condition (in line with our first hypothesis); however, placement into the rumination condition alone did not guarantee an increase in negative mood intensity.

Finally, we also hypothesized that participants with a greater level of depression would begin with a more negatively rated autobiographical memory at Time 1. A small correlation between depressive symptom severity and negativity rating at Time 1 showed that the results were in the predicted direction but not statistically significant.

The overall pattern seen in the current study was similar to that found in two previous studies. Lyubomirsky et al. (1998) found that people with dysphoria who ruminated once became more depressed, but people with dysphoria who were distracted once became less depressed. They found no significant changes in depressed mood in people without dysphoria who ruminated versus were distracted. Dysphoric rumination leads to retrieving more negative autobiographical memories and rating autobiographical memories as more negative and unhappy. Park et al. (2004) similarly found a greater increase in depressed mood with rumination versus distraction for participants with depression compared to participants without. In the current study, in the rumination condition, the higher a participant’s depressive symptom severity, the less their negativity rating decreased over time (i.e., the decline was shallower); however, in the distraction condition, the higher a participant’s depressive symptom severity, the more their negativity rating decreased over time (i.e., the decline was deeper). The results of the current study are similar to those of the previous two studies, but instead of finding an increase in negativity over time for the rumination condition, we found a diminished decrease in negativity rating over time.

Overall, evidence implicates rumination as a mechanism for the effect of depression on autobiographical memory. We offer a few possible explanations for this observed effect. First of all, studies of mood dependence and congruency in memory have shown that it is easier for someone to recall a previous episode when their current mood is congruent with their previous mood (Eich & Metcalfe, 1989). Thus, when someone is feeling sad, previous sad experiences may come more readily to mind when they try to think back. This can in turn feed into the availability heuristic, whereby things that come more readily to mind are judged as more frequent or probable (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973), leading depressed people to overestimate how often they have felt sad in the past or might again feel sad in the future. MacLeod and Campbell (1992) found that participants estimated higher probability of future negative events when they had been induced into a sad mood

and asked to retrieve unpleasant memories. Finally, rumination—that is, thinking about a sad memory over and over again—can serve to further strengthen that memory because of the wellestablished retrieval practice effect (i.e., testing effect; Roediger & Butler, 2011), such that the very act of retrieving a memory strengthens that memory, making it even more likely to be retrieved again in the future. Thus, rumination amplifies the effect of depression on autobiographical memory, and also further perpetuates depression itself. There were several strengths and limitations of the current study. One strength was that our results support findings from previous studies and were obtained using different methodology. A second strength was the use of the slider with a 0–100 scale which allowed for a greater range of results for the DV (negativity rating) than would have been obtained using a traditional 5point scale. A third strength was that the memory prompt successfully elicited specific negative memories from college students with an overall high mean negativity rating at Time 1 without a ceiling or floor effect.

One limitation of the current study was that it was completed using only a sample of college students. As such, it may be beneficial to complete a future study using a sample with a larger age range than what is generally provided by college students. Additionally, future research could investigate the extent to which antidepressants might influence the effect of rumination on negative autobiographical memories in participants with depression. Finally, a major source of variance in the current study was likely due to the variety of negative experiences that participants recalled. In order to reduce such variance, a future study could look at a negative experience designed by the researcher, or elicit negative memories with a more specific prompt.

Additionally, it may be beneficial to complete a qualitative analysis on the content of the negative autobiographical memories to investigate if the content impacts the effectiveness of distraction and rumination. Future research could also further investigate the relationship between depression and rumination in regard to how they interact with each other, for example to see if verbally describing a negative autobiographical memory or experience to an acquaintance in conversation (rather than simply thinking about it) leads to a decrease or increase in the negative mood intensity rating for that memory. Another topic of future investigation could be overgeneral autobiographical memories in the context of rumination in participants with depression, similar to studies such as one by Mitchell (2015).

The broader implication of this study is that depressed individuals may be susceptible to persistence or amplification of negative memories because of Roberts and Finley

ruminating on them. But they may be able to avoid this by distracting themselves from rumination. For example, college students who are distressed over a course experience may ruminate on their distress and thus become more distressed. However, by distracting themselves from the distress, students may be able to become less distressed and thus be able to focus more on other memories or cognitive processes. The results could also have beneficial implications for therapy and counseling as teaching patients who are in counseling or therapy to distract themselves from ruminative thoughts could be beneficial in terms of decreasing the intensity of their overall negative affect (Watkins, 2015).

References

American Psychological Association. (n.d.-a). Depression. In APA dictionary of psychology. Retrieved June 19, 2024 from https://dictionary.apa.org/depression

American Psychological Association. (n.d.-b). Autobiographical memory. In APA dictionary of psychology Retrieved June 19, 2024 from https://dictionary.apa.org/autobiographical-memory American Psychological Association. (n.d.-c). Rumination. In APA dictionary of psychology. Retrieved June 19, 2024 from https://dictionary.apa.org/rumination

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. (1996). Beck Depression Inventory–II [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t00742-000

Bianchi, R., Laurent, E., Schonfeld, I. S., Bietti, L. M., & Mayor, E. (2020). Memory bias toward emotional information in burnout and depression. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(10–11), 1567–1575. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105318765621

Conway, M., Csank, P. A. R., Holm, S. L., & Blake, C. K. (2000). On individual differences in rumination on sadness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 75(3), 404–425. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327752JPA7503_04

Eich, E., & Metcalfe, J. (1989). Mood dependent memory for internal versus external events. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 15(3), 443–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.15.3.443

Harrington, J. A., & Blankenship, V. (2002). Ruminative thoughts and their relation to depression and anxiety. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(3), 465–485. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00225.x

Hitchcock, C., Newby, J., Timm, E., Howard, R. M., Golden, A.-M., Kuyken, W., & Dalgleish, T. (2020). Memory category fluency, memory specificity, and the fading affect bias for positive and negative autobiographical events: Performance on a good day-bad day task in healthy and depressed individuals. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 149(1), 198–206. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000617

Lyubomirsky, S., Caldwell, N. D., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1998). Effects of ruminative and distracting responses to depressed mood on retrieval of autobiographical memories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 166–177. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.75.1.166

Lyubomirsky, S., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1995). Effects of self-focused

rumination on negative thinking and interpersonal problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(1), 176–190. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.1.176

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2000). The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109(3), 504–511. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.504

MacLeod, C., & Campbell, L. (1992). Memory accessibility and probability judgments: an experimental evaluation of the availability heuristic. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(6), 890. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.6.890

Mitchell, A. E. P. (2015). Autobiographical memory response to a negative mood in those with/without a history of depression. Studia Psychologica, 57(3), 229–241. https://doi.org/10.21909/sp.2015.03.696

Mitchell, A. E. P. (2016). Phenomenological characteristics of autobiographical memories: Responsiveness to an induced negative mood state in those with and without a previous history of depression. Advances in Cognitive Psychology, 12(2), 105–114. https://doi.org/10.5709/acp-0190-8

Park, R. J., Goodyer, I. M., & Teasdale, J. D. (2004). Effects of induced rumination and distraction on mood and overgeneral autobiographical memory in adolescent major depressive disorder and controls. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(5), 996–1006. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.t01-1-00291.x

Peeters, F., Nicolson, N. A., Berkhof, J., Delespaul, P., & deVries, M. (2003). Effects of daily events on mood states in major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112(2), 203–211. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.112.2.203

Roediger, H. L., & Butler, A. C. (2011). The critical role of retrieval practice in longterm retention. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 15(1), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2010.09.003

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1973). Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive Psychology, 5(2), 207–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(73)90033-9

Urban, E. J., Charles, S. T., Levine, L. J., & Almeida, D. M. (2018). Depression history and memory bias for specific daily emotions. PLoS ONE, 13(9). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203574

Vrijsen, J. N., Ikani, N., Souren, P., Rinck, M., Tendolkar, I., & Schene, A. H. (2001). How context, mood, and emotional memory interact in depression: A study in everyday life. [Supplemental Material] Emotion, 23(1), 41–51) https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000783.supp

Wang, Y. P., & Gorenstein, C. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: A comprehensive review. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 35, 416–431. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2012-1048

Watkins, E. (2015). Psychological treatment of depressive rumination. Current Opinion in Psychology, 4, 32–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.01.020

Author Note

Jason R. Finley https://orcid.org/0000000159218336

We have no conflicts of interest related to this project. Data are available at https://osf.io/h657r

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Jason R. Finley, Psychology Department, Box 1121, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, Edwardsville, IL 62026.

WINTER 2024

Is My Anger Justified? The Influence of Gendered Racial Identity Centrality on the Relationship Between Internalization of the Sapphire Stereotype and Disengagement Coping Among Black Women

Nailah Johnson, Makyra Farmer, and Danielle D. Dickens* Department of Psychology, Spelman College

ABSTRACT. Historically, Black women have been susceptible to the effects of race and gender related stress, such as the sexually promiscuous Jezebel or the motherly Mammy stereotypes. However, few studies have centered on the influence of the Sapphire stereotype—defined as being overbearing, emasculating, and aggressive—on Black women’s health. Due to these stereotypes, Black women may utilize different coping strategies such as disengagement coping—limiting one’s interpersonal interactions— to manage these stressors. Yet, little research has specifically examined how Black women’s gendered racial identity development relates to internalization of the Sapphire stereotype. The present study aimed to explore whether gendered racial identity centrality moderates the relationship between the Sapphire stereotype and disengagement coping among Black women. Two hundred ninetyeight Black/African American women between the ages of 18–52 completed an online survey via Qualtrics. Based on the Phenomenological Variant of Ecological Systems Theory, we hypothesized that gendered racial identity centrality will moderate the relationship between the Sapphire stereotype and disengagement coping. Consistent with the hypothesis, the results indicated that identity centrality significantly moderated the relationship between the Sapphire stereotype and the use of disengagement coping such that higher identity centrality decreased the association between the Sapphire stereotype and disengagement use (b = .51, SE = 0.09, t = 5.67, p < .001, 95% CI [.33, .69]). This research can be used to develop educational programs to promote healthy identity development among Black women.

Keywords: gendered racial identity centrality, Sapphire stereotype, gendered racialized stereotypes, disengagement coping, coping strategies

Diversity badge earned for conducting research focusing on aspects of diversity.

Historically, Black women have been—and continue to be—susceptible to the effects of race and gender related stress, considering their socially constructed identities of being Black and a woman (Greer, 2011). Lewis et al. (2016) concluded that other people often have gendered racial misconceptions about Black women’s behavior and treat them based on those beliefs. Oftentimes, Black women are labeled as the Angry Black woman, or the promiscuous Jezebel. Another lesserknown stereotype, the Sapphire, describes Black women as loud, emasculating, and aggressive (Bond et al., 2021). These stereotypes are connected to experiences of gendered racial microaggressions, defined as seemingly innocent yet harmful remarks based on one’s gender and race. Experiencing such gendered racial microaggressions has been associated with poorer mental health and coping strategies (Lewis et al., 2017).

In fact, Black women may manage stressful events regarding racism, colorism, sexism, and other forms of oppression by utilizing different coping strategies, such as religion/spirituality, social support, and disengagement coping (Hall, 2018; Holder et al., 2015; Kilgore et al., 2020). Research has shown that the use of more disengagement coping strategies, the process of limiting one’s participation in certain activities, groups, or situations, was associated with poorer mental and physical health among Black women (Lewis et al., 2017). Further research has shown that the importance of one’s race and gender identity, referred to as gendered racial identity centrality (GRIC), may positively or negatively buffer the relationship between gendered racism and coping strategies among Black women (Jones et al., 2021). Yet, minimal research has examined the significance of GRIC in minimizing the effect of internalization of specific stereotypes (e.g., the Sapphire stereotype) and the use of disengagement as a coping strategy. The purpose of the current study was to fill this research gap by understanding how GRIC moderates the relationship between internalization of the Sapphire stereotype and disengagement as a coping strategy.

In the present study, the Phenomenological Variant of Ecological Systems Theory (PVEST) was the main theoretical framework used to explore and contextualize the relationship between gendered racism and the coping strategies Black women use. This theory explains how various risk factors influence potentially stressful experiences, how individuals use various coping mechanisms, and how these mechanisms impact an individual’s behavior and health outcomes (Spencer et al., 1997). Previous research exploring racial discrimination in Black adolescents used PVEST to explain unique protective and risk factors associated with being Black (Seaton et al., 2009; Sellers et al., 2006). In one study, Sellers et al. (2006) used PVEST’s risk and resilience framework to examine psychological wellbeing with racial

discrimination as a risk factor and a stressor and racial identity as a tool for resilience and as a coping strategy. The researchers found more racial discrimination to be associated with more stress, more depressive symptoms, and lower psychological wellbeing, indicating that race is one unique factor related to stress among African American adolescents. Specifically exploring the experiences of Black women, Dickens and Chavez (2018) used PVEST to posit how race, socioeconomic status, and gender serve as risk factors that result in Black women developing reactive coping mechanisms, such as changing their behavior to fit their environment. Through conducting interviews, researchers found that Black women described changing their behavior, appearance, and perspective, also known as identity shifting, to navigate experiences of stereotyping and discrimination in the workplace (Dickens & Chavez, 2018). These results show that race, socioeconomic status, and gender act as unique risk factors that are stressors for Black women, which can lead to maladaptive coping strategies. In the current study, PVEST was used to show that experiences of gendered racialized stereotypes are risk factors that can cause stress for Black women and these stressors can influence the coping strategies that Black women decide to use, such as the use of disengagement coping strategies when faced with the stressors associated with being both Black and a woman.

Black Women’s Identity Development and Related Experiences

One factor that may buffer Black women against the harmful effects of experiences of stereotyping and discrimination is gendered racial identity centrality, which refers to how an individual’s gender and racial identity combined are directly important to that person’s overall sense of self (Jones et al., 2021). For example, some Black women may view being Black and a woman as important to who they are (i.e., their identity) and others may not. Many researchers have examined the extent to which Black women place importance on their race and gender identity (Jones et al., 2021; Lewis et al., 2017; Nelson et al., 2022; Szymanski & Lewis, 2016). Scholars have found mixed results on the influence of GRIC among Black women, such that some research has found that greater GRIC served as a protective factor in the face of gendered racism (racism and sexism; Lewis et al., 2017), and other studies found that greater GRIC was related to poorer outcomes when experiencing gendered racism (Jones et al., 2021; Nelson et al., 2022; Szymanski & Lewis, 2016). Specifically, research has found that more GRIC increased the positive relationship between identity shifting–changing one’s speech and actions to minimize experiences of discrimination–and depressive symptoms (Jones et al., 2021), and increased the positive

Johnson, Farmer, and Dickens | Gendered Racism and Coping Among Black Women