17 minute read

poem

Thanksgiving, a Feast

I think turkey, stuffing and cranberries, probably sweet potatoes and a green veggie would be enough, but Lee insists on corn pudding, Max only eats white potatoes, Sue says Waldorf salad is tradition and Randi’s roasted vegetables were a hit last year. And while the turkey roasts we’ll all be hungry so I buy bagels for lunch, smoked salmon, humus and guacamole, tortilla chips with salsa, Havarti cheese and crackers, dried apricots, figs and clementines on sale.

Sam just wants dessert and Bill assures him there’ll be pumpkin and apple pies, Jen’s brownies, Christina’s chocolate chip cookies, butter pecan ice cream and a box of truffles. And because it’s also Sue and Sam’s birthdays, Jimmy brought Krispy Kremes all the way from New Paltz.

But twenty pounds of turkey overwhelms the pan, I forget the giblets in the neck which reminds me of the book I used to read to my first graders, the one about the Tappletons, how the frozen turkey bounced out the back door, rolled into the pond, how the salad got fed to a pet, potatoes dripped off walls from an unwatched blender, pies sold out at the bakery.

But our family at long last feasts, the chutney with grapes gets rave reviews and even though I forget the coffee and tea (though no one complains), we feel satisfied and full, and like the Tappletons, we all agree, this Thanksgiving was special and it had very little to do with the food!

-Norma Ketzis Bernstock

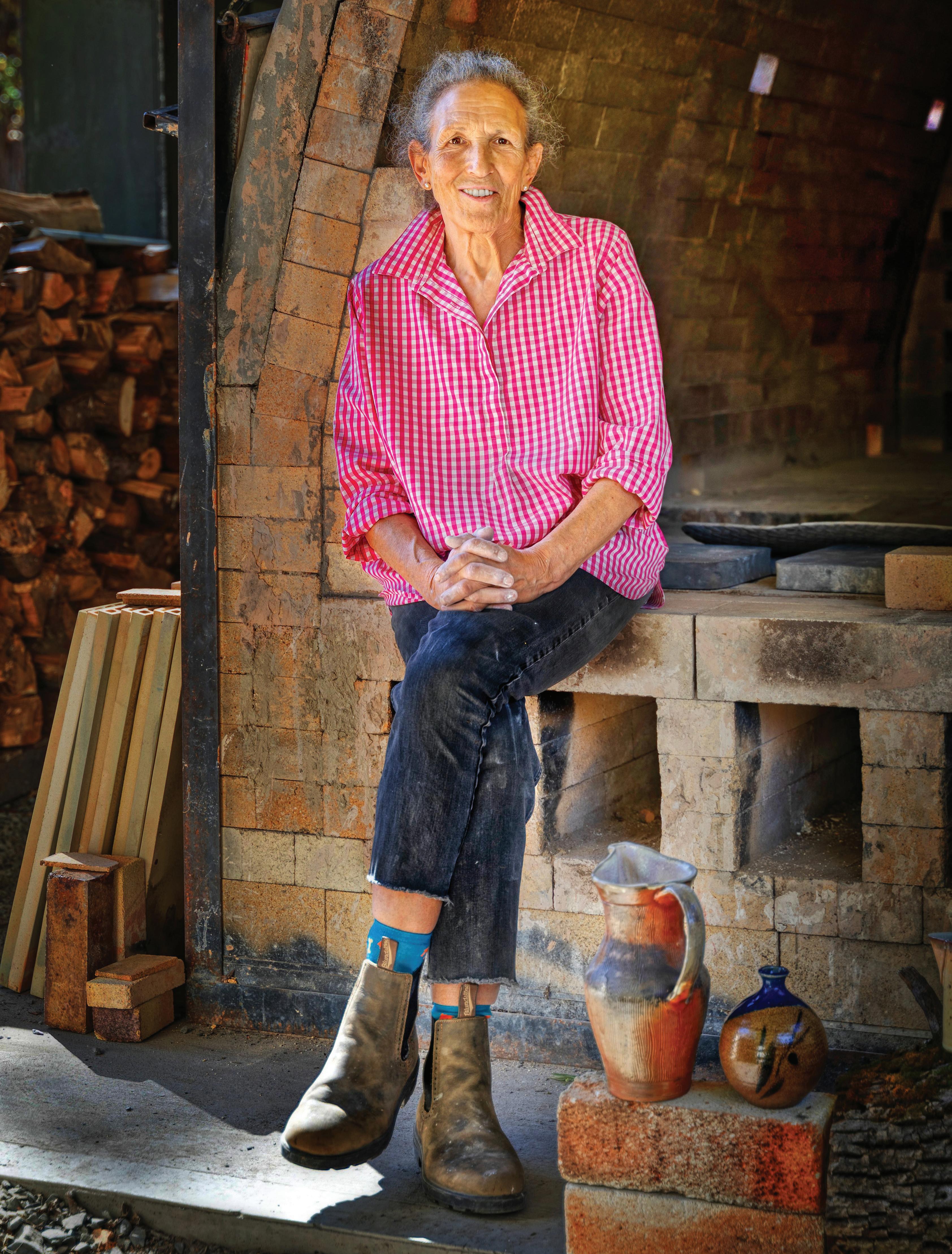

An Artist’s Journey Lynn Isaacson

How does someone evolve from conceptual artist, whose gigantic canvases dwelled in the intellectual realm of art history, to potter, whose utilitarian bowls, plates, and cups fit nicely on a kitchen shelf? Lynn Isaacson of New Prospect Pottery believes that serendipity played a big role in her journey, along with her day job, her friends, and even some New York City landlords.

On a recent afternoon, Isaacson sat in her spacious studio near Pine Bush, NY, and shared some of her many stories— some funny and all wise—about her long life as an artist.

“I got my MFA in painting, rented a tiny studio on Union Square, and had some work in galleries in the city. I was doing painting and sculpture and was one of the founding members of a cooperative gallery, the Noho Gallery on LaGuardia Place,” she begins. The gallery later moved to Soho, so the Noho Gallery was on Mercer Street in Soho.

Her early work can easily be called conceptual, based on ideas and concepts rather than the object produced. She constructed tight geometric, three-dimensional forms on her canvases, which she then painted. The painting grew out of color theory, the study of how colors interact. For instance, the same red line looks orange when surrounded by yellow but rose when surrounded by blue.

Isaacson repeated the resulting images, using them as modules to form large, complex canvases. “The geometry I used in my paintings was very regular, very tight, for a very long time,” she said. “I had gone to art school in the sixties when you had a blue canvas with an orange border. There was no sense of how it was even painted, so that’s what I did. I used little foam rollers and got rid of the hand of the artist because you just wanted the color to speak for itself.” She also worked very large, and that required some acrobatics in a miniscule New York City studio. “To line up the lines and the stripes, you had to be really precise. The piece was eleven feet long, and the only way I could do it in the tiny studio was to set the modules diagonally on a table and crawl under the table to get to the other side. I could not get far away enough to really see what it looked like, and I never saw it until I hung it in the bigger space at the gallery.

“I was in the studio maybe ten years,” Issaacson mused, “but it became oppressively expensive, so I had to give it up in the late 1980s. I knew I had to get rid of my living room furniture at home and work small. I also wanted to loosen up.”

At home, her materials changed, but the modules and stripes remained. She favored the American log cabin quilt design that uses strips of cloth to form the modules, repeated in different colors to make a quilt. “I also liked handmade papers, and I always did needlework, knitting, and things like that.

“I bought some vintage Japanese fabric—I don’t even know why I got that. The men’s kimono fabrics are geometric, while the ladies’ and children’s fabrics are floral. I really liked the geometric men’s fabric. I collected a lot of that, as well as handmade papers, to make the log cabin patterns, and then I would use them as modules. I would use the wrong side of the sewing. Then I started sewing into the paper with these gorgeous German threads. So, it was oil on paper, paper on paper, and fabric on paper.”

funded correctly. “I taught practically every kid in the school; it was like gym. You were used as filler. Maybe a class would meet once a week for forty-five minutes, and you had maybe forty classes every week. If you have 1,200 kids, you never get to know anybody.

“You are getting $250 a year for supplies,” she continued, “so you can’t even buy a pencil for everyone. I was very creative about it, but you need paint brushes; you need stuff. How much can you do with newspaper and flour and water? There is just so much that you can do. I needed to do something different. I needed a change of pace!”

A combination of smart politics, serendipity, and chutzpa created the opportunity that Isaacson needed. “I had just come off a year’s sabbatical at City College when the ceramics teacher at the school retired. I wanted to teach ceramics, but the school principal would not fund me.” Luckily, Isaacson had met a lot of people while on sabbatical, including some on the Board of Education.

She called a contact there who offered her funding directly from the board. “So,” she said, “that’s how my career in ceramics all started. I enjoyed it, the kids enjoyed it, and the Board of Ed was giving me money.”

Her art practice seeped into her teaching in ceramics class. “I did quilt design with them, modules. We used a lighting grid from the top of an elevator to cut out square tiles, and we did mosaics. And I taught math methods. We did a lot of stuff based on math.” She created images from numbers and dates, using, for instance, the Roman numeral II because her cousin had died on February 2nd.

Isaacson went on to teach near the Grand Concourse, where a friend opened a new school with a ceramics shop designed just for her, and at Lehman College, part of City University.

Outside of her teaching, the transition from painting to clay took awhile. “I was a painter!” she exclaims. “Still clay is really seductive, so I started learning about contemporary pottery. I didn’t even know what I liked. I remember seeing this cup, and it had a lumpy white glaze. I said, ‘Ewww, it looks like brains.’ But, I went online and bought a little cup from Japan with the creepy glaze. It was a red clay cup with white creepy, glowy glaze. I put it in my living room, and I looked at it every day. I fell in love with this little cup! I was looking hard at pottery and being astounded at what I ended up liking.

“It turns out that I really like very simple Southern pottery, American jugs from the South. Simple, plain, and, I guess, geometric. Where my paintings were all about color, I don’t think any of my pots are all about color. I like contrast between surfaces, but it’s more the form. A simple form is really hard to make. I still struggle.”

During the same period, sometime in the 1980s, she started to study seriously and to meet a series of potters that would help transform and shape her process. At the Art School at Old Church in Demerest, NJ, she studied with Susan Beecher, beginning a life-long association. At a conference in Florida, she met Earline Green, whose work on tiles Isaacson called “life changing.” But, during all this time, she had no pottery studio of her own.

A Wood Firing at New Prospect Pottery

Firing pottery in a wood kiln, essentially a 6’ x 15’ brick oven, takes teamwork, extensive expertise, and not a little moxie. After loading the pottery deep into the kiln, a team of 16–20 people work in round-the-clock shifts to gradually heat a wood fire within to 2200° over about three days, keep it steady, and then slowly cool the kiln over the days that follow. A doorway receives the wood, an open grate below glows with the embers, and small openings on three sides allow the fire to draw oxygen. The team moves rhythmically around the kiln, constantly peering into all the openings and watching for a lively fire that heats evenly throughout. The position of the logs, the evenness of the color of the embers, a tiny thermometer reading, the type of smoke coming from the chimney, and the sound, color, and movement of the flames—they miss no detail! Finally, with its insatiable appetite for pine, oak, and ash wood fed, its logs properly arranged, its embers evenly raked, and plenty of well-regulated oxygen, the wood kiln settles contentedly into producing beautiful finishes on the pottery harbored within.

Serendipity changed all that. She took advantage of her landlord’s eagerness for her to vacate her rent-controlled apartment so he could charge the market rate. “I ended up getting $75,000 for moving. A third of that went to Uncle Sam, and the rest went to the studio. Out I went from the city to upstate New York in 2006,” she said.

Once in Pine Bush, her practice, like the roots of the trees enfolding her new studio, began to spread out in ever-changing directions. “It was a slow start. I was selling some stuff in the farmers’ market maybe once a month, and I met some people there. I had one electric kiln.”

Susan Beecher was building a salt kiln at the Sugar Maples Center for Creative Arts, where she also taught. No one else she knew had that type of kiln at the time, so Isaacson joined the crew building it. The pottery she had admired for so long was all salt-fired, and she later built her own kiln for salt firing.

Meanwhile, a friend invited her to the firing of a kiln heated with wood. She had never heard of wood firing. “My friend used all the lingo, and I didn’t know what she was talking about. Whadda you mean? Ay yi yi! I’m looking at the pictures, and I hadn’t a clue.” They rented a van anyway and drove their pots out to Iowa where Ken Buchell, whom Isaacson already knew from Old Church, introduced her to the magic of wood firing. The advice I got was to go and fire in as many wood kilns as you can.” She learned the art and science of carefully loading the pots into the kiln, when to stoke, how to very slowly raise the temperature to around 2200°, and then how to very slowly cool everything off before opening the door. The opening of the door reveals the colors and patterns created by smoke, outside the control of the potters.

Because the firing usually takes about six days of roundthe-clock, tough work, a group must come together and work in shifts. The kiln must be montitored and tended, and the participants have to be fed and even housed.

“Sixty-five hours on your feet, carrying the logs, throwing º logs into a 2200 oven, flames coming out, you’re tired; it’s hard work. Barbara—she’s seventy-five years old—she drives up from Brooklyn. She’ll do an eight-hour shift. Hour eight, everybody else is exhausted, but she’s carrying logs—and she makes food! She usually brings bagels. Puneeta, a friend from Long Island, makes Indian food and will often bring things that she has made, so the place smells delicious, like the best Indian restaurant. It is so good!”

Usually, the participants stay in area B&Bs or hotels, but recently twenty people came to her home for a week-long workshop with Justin Lambert, the designer of Isaacson’s wood kiln. Her place resembled summer camp with meals served, plenty of hard work, and lasting friendships being formed.

“Every meal was here. [laughing] Food all over the place. Doug, who comes from Ithica, cooked the first two nights. I had hit the wall and never made 6 p.m. I had an eighty-threeyear-old woman and her husband on an air mattress in the office. I don’t know how they stood up. Doug was on an air mattress in the basement. People were sleeping on the couch. I woke up very early in the morning because the change of shift is at 5:30 a.m. I would get up and make coffee and tea at 4:30, then go out to the kiln. Afterwards, it took me a week and a half to just do the laundry. The towels, the sheets!”

Isaacson’s studio is, by now, something like a fascinating museum of pottery process. Her four kilns, electric, gas reduction, salt, and wood, each produce entirely different finishes. She creates her own transparent or opaque glazes, tailored to each piece being fired. Unlike many potters, she uses a variety of clays and fires at very high temperatures. She shares her vast knowledge and experience with anyone who passes through—and lots of folks do, constantly.

In spite of the endless possibilities of her studio, she has stayed with the discipline of simple and useful shapes. Her kitchen shelf looks like a jewel box full of precious plates and cups, just waiting to receive colorful Hudson Valley produce. Any bowl, plate, or mug bought from her website will allow the purchaser to luxuriate in drinking a rich morning coffee from a practical work of art. ......................................................................................... You can explore that everyday luxury at New Prospect Pottery on www.newprospectpottery.com. Or you can visit the studio with GOST, the Gardiner, NY, Open Studio Tour, slated to resume next spring.

The Forgotten Ruins in and around New Jersey’s Roadways Abandoned Beauty

Y

ou may pass them every day, and more often than not, probably don’t give them a second thought.

The skeletal ruins of a church along Route 94 in Frelinghuysen, a leviathan of a building that once was a mansion but now sits abandoned on the campus of a community college, or a once-majestic abbey lying just past the intersection of Route 206 and Stickles Pond Road, left to the cruel intentions of mother nature.

These were once vital, relevant buildings that were painstakingly constructed with care and the utmost attention to detail. For one reason or another—most of the time—due to a monetary concern, they have been left neglected, lay derelict and, to most, become an eyesore.

The photographer in me sees these as perfect subjects. My job as an image maker is to tell visual stories through places like the Spring Valley Christian Church, the Horton Mansion, or the Queen of Peace Retreat and Saint Paul’s Abbey, buildings full of character and history that is just begging to be shared. and have found it full of ruins of both historic significance and aesthetic value. And as many of them as I have found and documented with my photography, I am always delighted to learn of others that have remained hidden by the passage of time and the neglect of their caretakers.

I have made a bit of a career out of helping to save buildings like this. My favorite example is the 1799 Lazaretto, located outside of Philadelphia, which was slated for demolition. A group hired me to come in and photograph the building, top to bottom. It took three years, but we managed to save the structure, and it is now being restored, in small part because of my photography, and will serve both as a museum and municipal offices.

In my own small town of Ogdensburg, New Jersey, I found a hidden gem of historic substance in the old Fox Studio Film Vaults. The vaults were constructed in the 1920s and were used to store film, highly flammable celluloid reels. They were shipped across country by train and found their home right here in Ogdensburg. While there are no more reels to be found, the ruins of the vaults rest within the fences of a modern self-storage facility.

There are ruins of mills and mines, mansions and more littered throughout the hills of Northern New Jersey. It’s a never-ending photographer’s paradise of history, texture, color, and form. The trick has always been getting the necessary permissions to gain access to these structures, many of which pose certain physical risk to anyone brave enough to step through rotting doors or broken windows.

As a rule, I never trespass…ever. I want to document these buildings and be able to show my audience how they currently stand. I don’t want to have to worry about getting fined for trespassing when I enter a structure. Creativity is hard enough without having one foot out the door in case you see the cops coming. Doing what I do with all permissions granted is the only way I am able to truly capture the essence of a building. The question I get asked most about photographing these buildings is what gear I bring along with me. I do like to travel very light when I am on these sorts of expeditions, so it’s usually one DSLR, in my case a Nikon D500 with a super wide-angle lens attached. My preference is the Sigma 10-20mm. That lens affords me a very cinematic view when I am tucking myself into the corner of a room, and it allows me to capture up to three of the four walls surrounding me.

Join me now as I show you around my favorite locations in and around New Jersey. I’ve gained access so you wouldn’t have to and am very proud to show you these images! ............................................................................................ Paul Michael Kane will be hosting a program, “The Unseen Sussex County—Abbeys, Mansions & Mines” on December 2nd at 6:30 p.m. at the Sparta, NJ, Library.