5 minute read

Jules Pye - The Surprising Value of a Broken Mind

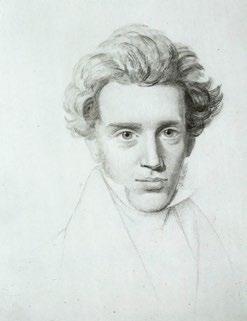

Kierkegaard – crises as wake-up-calls

The 19th century Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard lost all but one of his six siblings by the time he was 22. His traumatic breakup with his fiancée in 1841 and the death of his siblings – even if not that of his father – had a tremendous impact on him and his Philosophy. He is, like many others, a philosopher whose traumatic experiences have enabled him to think outside social norms, common sense and general opinion. In his case his Philosophy has gone towards how we should stop thinking we can know anything. We should stop pretending our lives are comfortable, happy or without mystery or paradoxes in any way. It is Kierkegaard’s struggle to come to terms with the reality of life, and his creative responses to it, that will bring this short essay to a close.

As mentioned, one of Kierkegaard’s main philosophical aims was to get us to wake up from our safe and cosy emotional illusions around work, love, family and a purposeful and meaningful life. Much like Nietzsche, he wanted us to see that life was wonderful because it was full of contradictions, paradoxes and unanswerable questions. For Nietzsche this ended in an embrace of life and its mysteries, whereas Kierkegaard ended up making his famous ‘leap of faith’. Kierkegaard had contempt for systems of thought that were overconfident in human reason – he was especially sharp in his criticisms of Hegel and his System, and of those in the Danish church who followed the Bible with little thought and were just going through the motions. And so, Kierkegaard, instead of trying to resolve the tension between subjectivity and objectivity, just threw himself on God. He described this leap as follows: “To have faith is to lose your mind and to win God”.

The ‘system-thinking’ that Kierkegaard opposed is similar to some of today’s ritual recyclers, polar bear mourners, ‘make-sure-you-turn-thelight-off-ers’, ‘technology-will-save-us-ers’ and ‘our-kids-will-solve-it-ers’. These people lack the depth of thinking and understanding of the scale of the problem that would lead them to realise the banality of their actions and beliefs. When tackling climate change intellectually and in terms of emissions, we need a similar approach to Kierkegaard’s: we also need to ‘lose our minds’, which can happen in two different ways.

Firstly, by thinking outside the box - or rather, outside the system; just like Kierkegaard continuously attacked “the system” of Hegelian idealism. We need to do this because the current one – which is purely focused on economic profit, based on the false assumption that the world has infinite natural resources and is totally tolerant of human interference – won’t be able to offer us any feasible solutions. And it isn’t just our disastrously consumptive system we need to change, we also need to change our ways of thinking when seeing ourselves as humans in relation to the rest of planet earth. We need to lose our current homocentric state of mind and realise that we, not just the fluffy polar bears and hungry pandas, will be pushed into an unrecognisably hostile environment by a climate that is growing out of control.

The second is to lose our minds by being ready to see how vulnerable we are. In Hobbes’ state of nature, there is a certain point of no return, beyond which tremendous effort is required to put the affected society back onto its feet (just like Somalia still hasn’t recovered from its time of anarchy). The same tipping points will happen with climate change, mainly on an ecological level. However, since humans are simply part of the world’s ecosystems, these breakdowns will pull us with them. The collapse of ecosystems will bring about the collapse of countries and societies; as ever less land is available for a growing demand of food, direct competition and confrontation with people will mount - pressures that will turn us into nervous ‘grabbers’, prone to aggressive and violent reactions. The potential for collapse must be made clear, so that we do not continue to make superficial responses.

Kierkegaard writes of his philosophical enlightenment: “I opened my eyes and saw the real world, and I began to laugh, and I haven’t stopped since.” When confronted with the reality of climate change and the necessity to act now due to its width and depth, one might let out a short-lived nervous laugh at the absurdity of the situation (before heading off to go and cry in the corner). When one sees how little has been done in terms of climate mitigation given the fact that the science has been rock-solid for over 50 years, one might laugh at the tiny amount of resolve politicians around the world are showing and how insufficiently and in a twisted manner the situation is covered by the media.

Climate change most definitely is not a laughing matter, but if we are not tempted to laugh at the sheer absurdity of the current situation then we have probably not been looking at it properly. Humanity, thousands of ecosystems and animal and plant species are at risk. We have no time to waste in laughing, unless we use it as a way of dealing with the absurdity of the climate state we are in, whilst keeping a sane and clear mind. Only then will we be able to solve the sixth mass extinction by being laughing children (similar to Nietzsche’s third metamorphosis, the child).

We need radical people like Nietzsche and Kierkegaard, who are not afraid to face the truth and live according to it. It is people like them who should become the role models of our societies, the ones who direct us, the ones who teach humanity to handle bare truths, the ones who make us sapere aude.

We have seen that different kinds of brokenness can lead to different outcomes. After having analysed Nietzsche’s example of a fatherless upbringing and Kierkegaard’s traumatic youth and early adulthood and the effects they have had on their philosophies, we have seen that these philosophers have managed to sublimate their tough starts in life into great thoughts and works.

They might even be able to help us tackle climate change, as they have found a way of dealing with absurd realities and brutal, devastating facts, whilst still holding on to and celebrating some kind of higher order; in Nietzsche’s case life and in Kierkegaard’s God. And so, it seems, that broken minds like theirs can help us face reality, react accordingly by seizing the moment and using the opportunity to possibly save us from the jaws of our own egoism.