24 minute read

Junior School - Learning through play

HOW DO I KNOW THIS?

For some time now, Kate Brown, our Head of Junior School, and I have shared deeply the ideals and research of Pasi Sahlberg and William Doyle. Since the publication of his book in 2019, Sahlberg relocated to Australia to become Professor of Education Policy and Deputy Director of the Gonski Institute at the University of New South Wales, Sydney. In a recent interview with ABC’s Sarah Kanowski (2020), Sahlberg reiterates through his personal experience, and the more recent experience of online learning during a world pandemic, that educators and schools need to lean in and listen to the powerful way play enables children to learn at their best.

Sahlberg (Kanowski, 2020) implores educators to make time and space for play to take centre stage in learning and in our schools rather than depriving our children of the outdoors. He encourages us as educators to get children off screens or, if using screens, use them to get students involved in design and construction, as the technology can be a tool to bring learning to life. He suggests children have more regular breaks amidst blocks of teaching instruction to help children and teachers to stay fresh and creative. Sahlberg predicts that learning and health outcomes can only improve by taking more regular breaks. He also encourages Australian educators to apply our gorgeous, relaxed Aussie attitude to schooling. Sahlberg’s experience has been that Australian schooling is serious and high stakes and more pressured than his experience in Finland.

YEAR 6 STUDENT

Guided Play. Year 4 entry event for the Term 3 Inquiry into Being a Sustainable Change Maker. The girls were given an experience by teachers to ignite empathy and curiosity for the environment. Senses were employed through what they could see, smell, hear and feel. They were guided to explore photos, video and objects that pose environmental concerns and solutions. Teachers reflected on how engaged the girls were as they looked at the items through the different lenses of empathy, as a scientist and as an historian. They were surprised at the connections students were already making between objects and its environmental element. Another teacher commented on how the multi-disciplinary approach made the entry event accessible to all students.

According to Robinson in Sahlberg and Doyle (2019, xv), play is typically viewed by many adults as ‘an enjoyable leisure activity, but unimportant compared with other priorities, especially in education’ which creates an important contradiction that must be explored. Furthermore, Sahlberg and Doyle (2019) recognise what many educators know, that parents are deeply worried about the uncertain future their children are facing. This can lead to parents placing an intense focus at home and at school on structured learning and achieving high grades. This is resulting in the opportunities for play being reduced and the value of play being held at a low level. According to the World Economic Forum (2020, p.8), “playful learning can enable innovation skills. Structured and unstructured play activities enable children to tap into their natural curiosity, learn through trial and error, and explore new solutions to challenges”.

The ideals and results that ‘play’ provide are featured in the recent publication of the NSW Curriculum Review Interim Report (2019). An intended outcome of seeking reform of the content of the curriculum is for “learning to be refocussed to develop deeper understandings and higher levels of skill” (p. xi). It is suggested that focus be placed on developing deep understanding through student understanding the relevance of their learning and how it can be applied to different contexts. Interestingly, the report gives focus to the evolving understanding of learning. It states that;

“Among the many things now known about learning is the crucial importance of emotional engagement … learning comes easily when it is driven by curiosity and passion. When motivated by personal goals, a search for answers, or something or someone they love, people are prepared to devote thousands of hours over many years to focused, purposeful learning” (p.6).

The document also points out that, “successful learning and effective recall are more likely when what is being learnt has personal meaning and when learners can see its relevance and potential applications” (p.6). Students need opportunities to apply these skills in practical, real-world contexts. Providing time and space for students to dive deeply into their learning in realworld contexts is an asset and requires students and teachers to take a ‘play mindset’ in the design of their learning. It requires us to be creative with integrating the curriculum to find that space. It requires creativity in designing learning opportunities that spark curiosity and develop passion in our students.

The NSW Curriculum Review Interim Report (2019) recognised that a common theme amongst submissions and consultations was the major role educators play in schools with regards to student wellbeing, mental health and the development of personal and social capabilities. It is my recommendation that schools provide more breaks, particularly outdoors, and more choice in play to increase student agency. This approach could see a decrease in student wellbeing concerns. According to an analysis by Dr David Whitebread, a Cambridge University psychology and education researcher (2016, as cited in Sahlberg and Doyle, 2019, pp. 54-55):

Intellectual Play. Year 3 students were given a problem at the beginning of Term 3, 2020, to design an enclosure for an Australian native animal affected by the bushfires in January 2020. The level of detail and description the girls provided to visiting students about their prototype designs was phenomenal. Their depth of understanding of the animal and its needs, which they captured through natural and recycled materials, demonstrated how providing guided play is beneficial to a child’s development and deep learning.

“Neuroscientific studies have shown that playful activity leads to synaptic growth, particularly in the frontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for the uniquely human higher mental functions. In my own area of experimental and developmental psychology, studies have also consistently demonstrated the superior learning and motivation arising from playful, as opposed to instructional, approaches to learning in children. Pretend play supports children’s early development of symbolic representational skills, including those of literacy, more powerfully than direct instruction. Physical, constructional and social play supports children in developing their skills of intellectual and emotional “self-regulation,” skills which have been shown to be crucial in early learning and development.”

A final source of confirmation to encourage us to further embrace the elements of play in our Junior School have derived from the Lego Foundation in a White Paper (2017) Learning through play: a review of the evidence. It is suggested that “through active engagement with ideas and knowledge, and also with the world at large, we see children as better prepared to deal with tomorrow’s reality – a reality of their own making. From this perspective, learning through play is crucial for positive, healthy development, regardless of a child’s situation” (p.1). The paper also recommends that “together with a sense of agency, we suggest that joy, meaningfulness, and active engagement, are necessary for children to enter a state of learning through play, and the addition of any combination of the other two characteristics (iteration and social interaction) supports even deeper learning” (p.16).

WHY NOW? HOW DID I KNOW THAT NOW WAS THE TIME TO BRING CHANGE?

We had just faced the transition back to school from online learning, due to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Teachers’ digital skills had grown exponentially, along with their flexibility of thinking. We needed to condense curriculum, integrate where possible and add more breaks to the girls’ day to balance the shift to online from face to face learning.

“I loved the idea of Challenge by Choice and passion projects throughout online learning. Allowing the girls to have space to play, create and learn about what really interested them was so beneficial”. Evie Charles (Year 5 Teacher)

“Having shorter lessons made us focus on what was really important verses superfluous information that can distract from the core of the learning objective.” Jenny Dreverman (Learning Support Teacher in Year 4)

“Disrupting the timetable allowed the girls to have more flexibility to demonstrate initiative in their learning, as well as flexibility to extend and demonstrate deeper connections in their learning. I found this exciting as a teacher because it opens up the possibility of greater integration across key learning areas and greater opportunities for rich, meaningful and connected learning.” Monica Medeiros (Year 6 Teacher) This enabled the vision of two leaders, Kate Brown, Head of Junior School, and myself to bring into the forefront our beliefs about the essential role that play has in a child’s development and her learning. We searched for ways to provide more time and space in the timetable and curriculum to give the girls time and space to play. We were committed to the value of ‘unstructured play’, play that is unguided by an adult and which involves freedom and choice for the child, and then to the value of creating time and space across all lessons to play with concepts and ideas; guided play and intellectual play. We believed that if we released our students in their lesson time by providing transdisciplinary units, choice and more inquiry style learning, then the imagination would be engaged - which is, therefore, play.

WHAT ACTION DID WE TAKE?

We started small by taking what was in our hand, the curriculum, to see if we could design and craft the learning for Semester 2 2020 in such a way that would give us more time and space. The best way to test our ideas was through the format of an action research project.

Using our research question: How do we find time and space to play for deep learning to occur? We decided to test two interventions.

Intervention 1: Year 3 and 5 timetable would be revised with more breaks and the use of a ‘challenge by choice’ grid.

Intervention 2: Year 4 and 6 timetable would be revised to provide more integration across subject areas, to enable a larger block of time to be

devoted to play. A new lesson, called ‘Inquiry’, was created which integrated several subjects and adopted an inquiry (play like) approach to learning.

Methodology

1. Conduct Year group collaborative planning days to redesign learning for Semester 2, 2020.

2. Gather data on ‘feelings towards the timetable’ from students, staff and parents via online surveys.

3. Ask staff to keep a journal of the experience and share at Year group meetings what they were puzzled by and inspired by in this action research project.

4. Students and staff asked to capture moments of play through digital photography.

5. Consolidate understanding of staff and create a new set of data through evidence gathered so far.

Evidence emerging from the data

What is ‘Play’ for children at Pymble?

• “I think play is a way to express creativity and make things using teamwork and imagination. I love play because there are no boundaries of what something can become. I love play because I have the freedom to turn a piece of junk into something amazing, we can use pure imagination, creativity, materials and teamwork to make something awesome. Most of all I love play because we can have fun with friends.” Anika Verma, Year 3 student • “I think play is joyful, fun, happy, friendly, like a trip to paradise of happiness!” Jessica Pickford, Year 3 student

Unstructured Play has its place in the school day.

• “I can be creative and have fun.” Year 3 student

• “During unstructured play, my friends and I started making perfume by crushing flowers to get oils. I was fascinated by the making of perfume and I did some research and used a STEM perfume kit at home to make my own perfume.” Saskia Nicholson, Year 5 student Intellectual Play through the Year 6 Deep Space unit provided freedom, choice and a sense of calm. Student comments include:

• “I love that we have freedom because that makes us able to learn in the way we do it best.”

• “I feel I am allowed to be more creative.”

• “I have choice and that makes me happy.”

• “I can be as productive as I want to be, that is up to me.”

• “I liked doing the mosaic tiles in deep space time because it was a time to do something I have never tried and also with friends that I haven’t learned with before.”

Unstructured Play with Year 3. “Mrs Plant, look! This is a bird nest and bees are attracted here too [pointing to the flowers]. We still need some shade for the birds so they won’t die in the heat today”. This demonstrates the incredible power that freedom of unstructured play gives to children to process and express either their interests or what they are learning about in class. The social and emotional element of this session of play was so strongly evident through the negotiation and collaboration required between students.

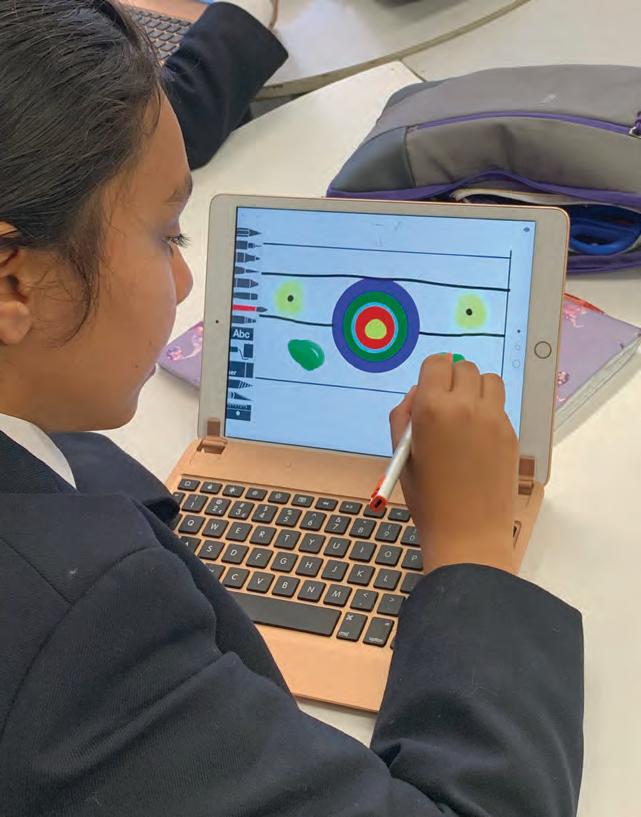

Intellectual play in Mathematics. Students were asked to design a flag linked with their Inquiry in the Year 5 unit, ‘Colonisation of Mars’. Their flag had to have several mathematical components of 2D shapes such as parallel lines, shapes and symmetry. It was incredible to see the high level of students’ engagement and the variety of designs. It certainly took learning to a deeper level that engaged imagination and, therefore, creativity and design. Emerging data from Staff

1. A deeper and cohesive understanding of where play sits in the school day for children is present in staff reflections.

Teacher 1: “Reflecting on practice and what I’m seeing - play is more than just one lesson. It should be part of the curriculum! Activities should be designed for students to play, explore, and collaborate. The process of play and discussion makes students grapple with ideas and words and concepts.”

2. Interestingly, as we have carved out time and space in the timetable, it has given staff a sense of freedom and peace leading to their own intellectual play with how learning is designed in their classroom.

Teacher 2: “I have enjoyed seeing the girls grow in creativity and freedom to experiment. For myself, it has been a learning curve to let go of the reigns and trust the girls with freedom. Also, remembering that assessment isn’t required of everything. I have loved being creative with the girls. Being able to enjoy a “freeer’” timetable and follow the path of the girls’ interests when completing discussion and activities has also been enjoyable. It has been easier to differentiate the lessons.”

LEARNINGS SO FAR…

Learnings

Developing a shared understanding of play in our community has required us as leaders of the research to find ways to check in with all participants and continually refine the understanding and in some places the value participants have placed on the word ‘play’.

The parent voice was not strongly represented in the data.

A collaborative planning day is an important tool for change as it brings all staff on board with the journey of learning they desire to take the girls on. This creates a shared vision of finding time and space to play

The ways in which children value and appreciate play is not always shared with adults. We need to align our vision with the place that play has, and can have, in schooling.

Students deeply valued the new subject ‘Inquiry’, finding it “different”, but freeing, as they were able to spend more time delving into the content.

Students in Year 6 valued the Deep Space ‘intellectual play’ unit. They commented on choice, connection with others and a sense of calm.

Students in Year 3 and 5 valued regular breaks in their timetable Next Steps

Continue to work with staff on a shared understanding of ‘play’. Continue to use teachers’ time in collaborative planning sessions and in discussions at year group meetings to foster the shared vision of finding time and space in timetable and curriculum. This will help us understand and better articulate the ways in which play is learning.

Find ways to engage and educate our parents, as research shows parent understanding and involvement in an initiative is an important precursor to change.

Collaborative planning should be scheduled to occur prior to each term. It would be great to invite specialist staff in PDHPE and Language/Arts to be part of this planning to see if more integration can occur across more subjects.

Include more debriefing and reflection opportunities after times of unstructured play to help students reflect and value what learning took place during that time.

Continue Inquiry time into 2021 through design of learning which is lead by themes, rather than topic units. The adoption of Deep Learning Pedagogies will take this even further.

Continue this in the timetable into 2021.

Include in the 2021 timetable regular breaks in which bodies can move. These are times when students are removed stretch and move and have a small snack.

Table 1: Overview of key project insights and next steps

CONCLUSION

Adapting our school structure, its timetable and the way we design learning, has brought incredible benefits for students and staff. In 2021, the timetable will provide a movement break for students after no longer than 55 minutes of learning. These breaks take different shapes. There is a movement break between Compass Check in and Period 1. There is another movement break of 5 minutes between Periods 1 and 2 and Periods 3 and 4.

There is also the ability for consumption of food during all breaks, as data gathered from the girls showed they were hungry throughout the day. We have maintained a recess break of 20 minutes and a lunch break of 45 minutes. In total, students now have 70 minutes of ‘break time’ in their school day. In the Netherlands, schools have 75 minutes of break time in their day and finish the school day at 1pm. We have also designed the timetable to enable a set time of unstructured play per fortnight for Year 3 to 5. Year 6 will continue with ‘Deep Space’ but we have chosen to rename the unit as ‘Passion with Purpose’. This will now have a direct link to students’ inquiry topic for the term, as well as a service learning element.

We will continue the Integrated Units of Inquiry in 2021, and will be adopting the Deep Learning Pedagogies, which is an exciting new development to move this action research towards. Future action research in the Junior School will be able to ask how the Deep Learning approach is enabling teachers to design learning which sees guided and intellectual play take centre stage.

Finally, if we are to nurture our children’s hearts, minds and souls, it is paramount that we find a way as a school to create time and space to play. I value how Dent (2005, p.50) links play to a child’s wellbeing in the following quote;

Play has the added advantage of giving children the opportunity to learn how to wait, share, take turns and to work alongside one another. Non-directed play is also essential for a healthy imagination. A healthy imagination is an excellent antidote to pessimism, negative thought patterns and unhappiness. If anything, this action research project has taught me to value even more strongly my thoughts on where ‘play’ sits in how a child spends her time. It has taught me to more deeply appreciate the freedom students are given when they can have even greater choice in how they allocate their time. I have also come to recognise the subtle, but all important, social skills that arise in unstructured play. These are vital and more sophisticated than we can construct in any structured planned activity.

The deeper learning through intellectual and guided play has enabled more connection, motivation and sparked more joy in our learners. Isn’t that what we desire as teachers; to spark a love of learning in each of the children we have the privilege to teach?

Lessons and breaks

8.15 Compass Check in 8.25 Period 1

9.25 Movement Break

9.30 Period 2

10.25 Recess – Play break 10.45 Period 3

11.45 Movement Break

11.50 Period 4

12.45 Lunch – Play break 1.30 Period 5 - Compass Directions 2.00 Period 6

Table 2: Junior School timetable, 2021

“In play, away from adults, children really do have control and can practice asserting it. In free play, children really do have control and can practice asserting it. In free play, children learn to make their own decisions, solve their own problems, create and abide by rules, and get along with others as equals rather than as obedient or rebellious subordinates. In vigorous outdoor play, children deliberately dose themselves with moderate amounts of fear – as they swing, slide, or twirl on playground equipment, climb on monkey bars or tees, or skateboard down bannisters –and they thereby learn how to control not only their bodies, but also their fear. In social play children learn how to negotiate with others, how to please others and how to modulate and overcome the anger that can arise from conflicts. Free play is also nature’s means of helping children discover what they love…none of these lessons can be learned through verbal means; they can be learned only through experience, which free play provides. The dominate emotions of play are interest and joy.” (Gray, 2013 p.18)

References

Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority (ACECQA). (2020). The Importance of Play in Children’s Learning and Development. Retrieved from https:// www.startingblocks.gov.au/other-resources/ factsheets/the-importance-of-play-in-childrens-learning-and-development/ Dent, M. (2005). Nurturing Kids’ Hearts and Souls. Murwillumbah, NSW: Pennington Publications. Ginsburg, K. R. (2007). The Importance of Play in Promoting Healthy Child Development and Maintaining Strong Parent-Child Bonds. Paediatrics. Official Journal of the American Academy of Paediatrics. Retrieved from https://pediatrics. aappublications.org/content/ 119/1/182?fbclid=IwAR0Xu8aiviBpd9bKa Uqi0mMllUcFt7YvoXxpNY9c8EghK8aBLt3A2k W8368#sec-2 Gray, P. (2013). Free To Learn. New York: Basic Books Group. Kanowski, S. (Host). (2020, June 4). Pasi Sahlberg – making school the happiest place to be. [Audio]. Radio. In Conversations. ABC. https://www.abc.net.au/radio/programs/ conversations/pasi-sahlberg/12298494 NSW Education Standards Authority. (2019). Nurturing Wonder and Igniting Passion, designs for a Future School Curriculum: NSW Curriculum Review Interim Report. NSW Education Standards Authority. Robinson, K. (2019). Forward. In Sahlberg, P. & Doyle, W. Let the Children Play. (pp xii). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Sahlberg, P. & Doyle, W. (2019). Let the Children Play. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Sahlberg (2020, August 6) Let the Children Play with Pasi Sahlberg – The State of Play. ACEL. https://kapara.rdbk.com.au/landers/ fcc5fd.html Whitebread, D. (2019). Chapter 3. In Sahlberg, P. & Doyle, W. Let the Children Play. (pp 5455). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. World Economic Forum. (2020). Schools of the Future Defining New Models of Education for the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Switzerland: World Economic Forum. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/ reports/schools-of-the-future-defining-newmodels-of-education-for-the-fourth-industrialrevolution Zosh, J., Hopkins, E.J., Jenson, H., Liu, C., Neale, D., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Solis, S.L. & Whitebread, D. (2017). Learning through Play: A review of the Evidence. Lego Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.legofoundation. com/media/1063/learning-through-play_ web.pdf

The power of kindness

Learning to positively impact our world

BY KATE BROWN

WHAT IS IT?

‘I think kindness is probably my number one attribute in a human being. I’ll put it before any of the things like courage, or bravery, or generosity, or anything else… Kindness - that simple word. To be kind – it covers everything to my mind. If you’re kind, that’s it.’ Roald Dahl

In the current political, economic, social and environmental climate, having something like kindness to believe in is vital for giving our young people hope. Our world has faced a global pandemic, reports of increased anxiety and mental health issues abound in the media and there are concerns of social fragmentation, and a loss of community. Alongside this is a growing movement within schools and local communities centred around kindness. It has become cool to be kind! Kindness may be a simple word, but it appears to be enjoying a revival and holds significant power. It is also a word that young children understand. Children know when someone is kind and, equally, they are able to articulate when they see, hear or feel someone being unkind. Learning to be kind is not just about creating a feel-good factor. McKinsey and Company, the global management consultancy company, expounds that soft skills are necessary for people seeking employment in our global economy. Identifying compassion and kindness as one of these critical soft skills, McKinsey and Company explain that employing people who exhibit positive interpersonal skills is vital for a harmonious corporation culture and is something they look for when considering leadership opportunities.

The NSW Curriculum Review Interim Report, Nurturing Wonder and Igniting Passion, explored how our rapidly changing world, with its developments in technology, social media, employment prospects and global issues, impacts how our children learn and need to learn. Human nature is instinctively social; people need people. The world we are preparing our girls for continues to evolve rapidly, and the ability to build and maintain strong positive relationships is identified in this report as a key skill that children need to learn at a young age to transition through adolescence and into adulthood.

Focusing on ways to build a tool kit to navigate mental health is seen as a priority within a school curriculum. Kindness could be the key to that tool kit.

WHAT IS KINDNESS?

So, what exactly is kindness? How can it be defined? How can it be measured and what benefits does it have for student growth?

Many reports including show a correlation between random acts of kindness and increased levels of happiness in the person doing the act of kindness (Dulin, Hill, Anderson & Rasmussen, 2001). However, despite all the current attention on kindness there are still difficulties in defining kindness. Whilst we may not be able to provide a definitive definition of kindness, children are, by the age of five, beginning to develop the capacity to feel and articulate empathy and, by the age of eight, developing the cognitive ability to begin understanding differences in perspective (Caselman, 2007).

It has been said that the origins of the word kindness lie in ‘kinship’, but over the centuries its meaning and purpose have been expressed in different ways. Whatever the etymology, there is a palpable power when children give of themselves to help others and the children themselves feel it. A 2015 study by Canter, Youngs and Yaneva found that kindness is something more than empathy for another’s situation as kindness requires both a reaction to another’s situation and action. Action research undertaken in the healthcare system provides scientific evidence for the impact that kindness can have on our brains. Ballatt and Campling’s (2011) findings from this research show that acts of kindness release oxytocin and endorphins and create new neural connections and increase the plasticity of the brain. So, being kind to others has a mutually beneficial effect on the giver.

There is still limited research, especially in terms of the impact of kindness on children and young people’s wellbeing, so we are keen to continue our observations and action research in this space. It is important to keep kindness on the agenda within schools so that children are taught to act with kindness and compassion to others, their environment and themselves and then go out and positively impact their world.

ACTING WITH KINDNESS – OUR JUNIOR SCHOOL APPROACH

Reading the available research on the power of kindness has led us to develop and embed a focus on three tenets of kindness within our Pymble Ladies’ College Junior School Mind, Body and Spirit continuum and curriculum. Central to our thinking has been the need for our young girls to be able to understand and articulate what kindness is and why it is important. We focused on developing the girls’ understanding of kindness through three lenses: kindness to others, kindness to the environment and kindness to self. Data collected through our wellbeing survey in 2020 and through focus groups showed that the girls’ reaction to the increased focus on kindness was resoundingly positive.