Don’t shoot the messenger

Addressing racism in schools through student-developed curriculum

This article was written by three (now former) students, Faye Chang, Isharah Hewavitharana and Fiona Fu and their teacher, Dr Sarah Loch, at Pymble Ladies’ College, in an unusual writing collaboration, but one which enables reflection. The aim of the article is to encourage other students, teachers, school leaders, and academics researching this field to strive for the inclusion and evolution of student voice in racism education and prejudice reduction learning programs.

DR SARAH LOCH, FAYE CHANG, ISHARAH HEWAVITHARANA AND FIONA FU

This article was originally published in the AHISA Independence Journal (Vol. 49. No. 1 May 2024)

1 Pymble Institute

The article explores the development of an anti-racism education program arising from student voice at Pymble Ladies’ College, NSW. The program evolved as senior students requested explicit education about topics of microaggression and racism in the school curriculum and teachers responded to and supported student advocacy and leadership in this area. A collaborative process between students, teachers and an academic researcher resulted in a series of lessons being co-developed, explored and evaluated. Student voice was central in stimulating the initiative which was implemented by and within the student body.

The students and teacher journeyed together over a three-year period (the students’ final two years of school and one year postschool) with the goal of making a difference to understandings and experiences of racism, prejudice, stereotyping, inclusion, and diversity of experience and thought in our school and others. One of the college’s strategic pillars is Social Intelligence which aims to enable the community to share stories and become active in cultural diversity activities which in turn build awareness, understanding and respect.

The Pymble Ladies’ College community is made up of a diverse mix of people from many cultural, racial, religious and linguistic backgrounds. Our school is a relatively harmonious and inclusive environment for students and staff. While there were no ‘huge issues’ we aimed to ‘fix’ through our project, the student group formed to represent students who had encountered a lack of understanding towards their cultures and who recognised amongst their peers a desire to expand intercultural knowledge.

Continually deepening and expanding awareness of diversity and inclusion is an action all schools should be taking and there are significant benefits in activating non-Anglo voices within schools to lead this learning.

Coming from this stance, the students requested meetings with staff to explain topics they wanted to see taught to reduce issues such as unconscious bias and microaggressions. The teachers in the team could see the challenge in delivering lessons in antiracism education, considering uncertainty in teacher knowledge and confidence. However, they were highly supportive of the students’ ideas. We all had personal motivations for investing in the process of advocating for and developing anti-racism and prejudice reduction curriculum in our school:

“At the beginning of the pandemic, the rise of hate crimes against Asian elders made for a volatile political and personal landscape. While we were lucky to escape the physical impact of these attacks, as someone living with their Chinese grandparents, I felt the emotional brunt keenly. Compounded with the lack of significant discussion at school around these issues, as well as seemingly superficial attempts to promote harmony and diversity, it was clear that, as students, we would need to create change ourselves.”

– Faye

The initiation of the anti-racism and allyship curriculum came from a motive of educating others and raising awareness, especially at the start of the pandemic when there was a sudden outbreak of racism and xenophobia. It was as if the world had forgotten compassion

and decided to use the chaos of COVID-19 as a time to spread hate and prejudice to Asian communities. It was difficult to feel like there wasn’t a target on your back whenever you stepped outside.” – Fiona

“Many of the conversations surrounding anti-racism did not include marginalised ethnic groups. As a result, much of our school’s activism (while well-intentioned) was less effective in targeting racial issues, oftentimes ‘glossing over’ issues of divide in favour of focusing on unifying aspects such as diversity and inclusion. While celebrating cultural harmony is important, these anti-racist measures were less effective, as people didn’t reckon with the ugly and uncomfortable reality of racism happening on school grounds and beyond.”

– lsharah

“I’m the Director of Research and also a History teacher. I’ve been a teacher for 25 years, with some experience in academia. My role also involves leading the Social Intelligence strategic pillar which is what brought me into this space with the students. I knew this would be a complex area but knew how committed these students were to seeing change happen. At times, the project felt like it was too much but I reflected it should not be this way.

I am a teacher, I’m educated and committed but I’m also white, have only lived in Australia and haven’t been on the receiving end of a racist attack or fear through my skin colour, accent or language. I know I can support these students in their efforts but am not sure how.”

– Sarah

The space between being advocates

2 This article was originally published in the AHISA Independence Journal (VOL 49 NO 1 May 2024)

Don’t shoot the messenger

and being educators is an important one. The students learned in this process that advocacy can be especially emotional. It can involve bringing up difficult emotions and experiences, and the students didn’t want anyone’s story to be twisted or misrepresented for the purpose of creating an educational course. Taking such complexities to heart, in this article, we aim to demonstrate how schools can empower students in decision making and change making in this important area.

Caroline Lodge1 encapsulates school students’ involvement in school improvement initiatives by mapping aspects of their involvement along two axes, moving from passive to active, and from having only functional input to having community impact. We aim to demonstrate how student voice can move along the axes towards making an impact in a school community by giving students a leading voice in knowledge-making.

THE BEGINNING OF THE PROJECT

The project emerged in 2020 and 2021, during the COVID-19

pandemic, when many students around the world brought to school an additional layer of vulnerability as they absorbed news and social media and heard of strife in other countries. Faye, Fiona and Isharah, along with a large group of peers, wanted to bring more education about race, racism and discrimination into the Pymble curriculum to prevent such issues occurring in our local communities. The title of this paper includes the phrase ‘don’t shoot the messenger’ which reflects the feelings of vulnerability the students felt by raising race, racism and prejudice at school through their initial meetings with teachers. The students were putting themselves forward in a very open way and their attitudes and beliefs were now public. They were not concerned about their reputations amongst their peers for raising the project, but were conscious of how peers would regard the lessons they wanted to develop and whether the lessons would be well-received. Fortunately, this was a consideration which the group trusted their teachers to help them navigate.

The student group began meeting with a group of staff leaders, including the Deputy Principal, Head of Senior School and Head of Secondary Wellbeing, to discuss ideas about anti-racism curricula. The group quickly showed their commitment by presenting sample lessons the school could use. These included the context and history of racism in Australia, allyship, stereotypes, casual racism and incidents of microaggression, cultural appropriation, representation in the media, colourism, and the white saviour fallacy. The teachers in the group readily acknowledged the value of explicit anti-racism and prejudice reduction education but felt colleagues would need time to grasp important terminology and content and opportunities to explore issues themselves.

Honest and frank discussion within the group also identified that while the proposed content could give students knowledge about racism and discrimination, it wouldn’t guarantee behaviour change. The teachers felt that more exploration was required to identify the best

3 Pymble Institute

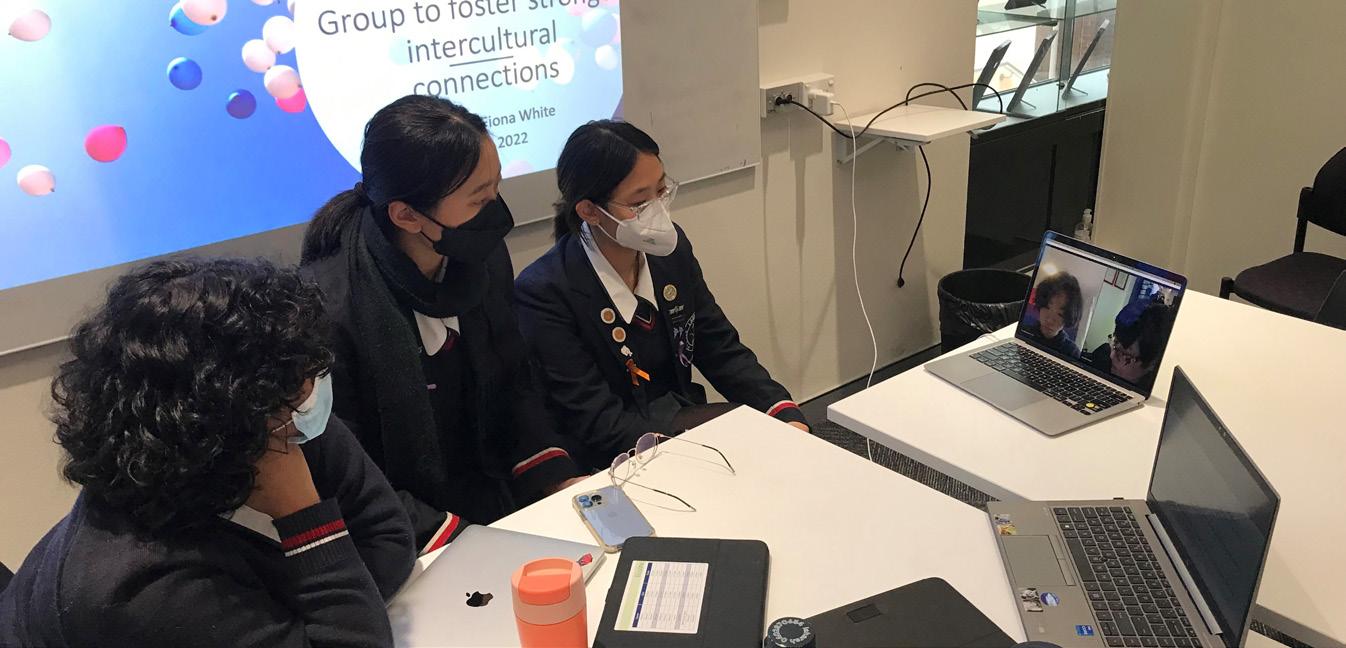

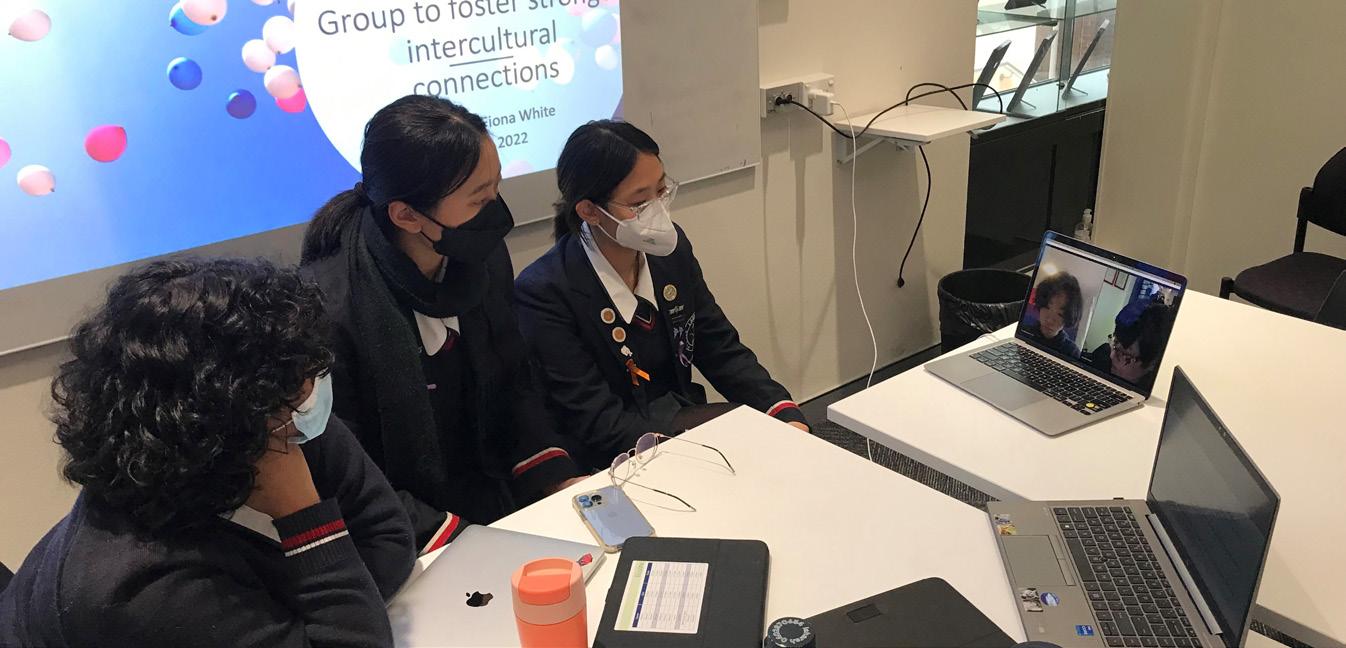

Students meeting online with Professor Fiona White

Don’t shoot the messenger

ways to teach prejudice reduction, to understand whether it was already being addressed in other courses and to see how it could fit it into the existing Year 12 wellbeing program, as this had been identified as the most likely starting point. From here, it was clear that school leadership was supportive of the initiative, but pathways still needed to be forged if student voice was to go further than simply raising the issue and making suggestions towards a solution.

WORKING WITH AN ACADEMIC PARTNER

There was now a defined group of six students leading this project and their voice around anti-racism education in the school was growing. The group maintained an ongoing discourse with peers in Year 12 and in other year groups by asking fellow students what they thought about the project’s tasks and actively asking for feedback on topics the curriculum was covering. It was becoming clear to the teachers that to progress the students’ goals, teachers needed support to feel sufficiently equipped to teach the lessons and teaching approaches needed to aim for maximum student engagement.

To assist in securing the professional learning the teachers knew was required, the group took advantage of a college-funded professional learning grant to engage Professor Fiona White from the School of Psychology in the Faculty of Science at the University of Sydney to work with the group. Fiona had recently been the academic advisor on the ABC TV series, ‘The School That Tried to End Racism’2 (Karabelas, Woodward, Foley & Ozies, 2021). The students researched Professor White’s background, as well as some other academic and community

leaders in the antiracism field, and all agreed that Fiona’s experience with schools and the academic field was a good fit.

Professor White began meeting online with the core group of students and teachers and helped refine the students’ broad curriculum into three lessons for the Year 12 wellbeing program. The lessons were titled Where does racism stem from and how can we reduce it?

Understanding and deconstructing racial stereotypes, and Let’s talk about race and media and would be delivered in a fortnightly sequence. The group also planned teacher professional learning and established a research study involving Year 12. White brought more than resources and expertise to the project. Importantly, from the student perspective, she also brought legitimacy to the students’ experiences and to their desire to make a difference. The messengers had an ally and a mentor who understood their drive and their need to have a voice around racism.

White introduced an instrument from her research, the Cultural Issues Scale (CIS) (White & AbuRayya, 2012)3 which was used to craft a schoolspecific, pre and post intervention survey to evaluate the impact of the lessons. The CIS measures blatant and subtle racism by asking respondents to rate the seriousness of scenarios including making a joke about someone’s background and not enrolling a student in a school because of their culture. The research study (White, 2022, unpublished) involved around 200 Year 12 students and it indicated that, prior to the lessons, ratings of both subtle and blatant racism were low in the cohort. The

postintervention survey revealed a reduction occurred in both subtle and blatant racism. There was also a rise in students’ metacognitive cultural intelligence which could likely be attributed to the impact of the three lessons.

ANTI-RACISM CURRICULUM: A STARTING POINT FOR ACTION

“The drive for raising empathy and understanding for marginalised groups became more prominent and eventually materialised in the form of our curriculum.”

– Fiona

“Like any message. the curriculum was a starting point for action. It conveyed that racism was still a prevalent issue that needed to be actively targeted through consistent. effective measures rather than on certain days that reminded us to do better.”

– lsharah

The anti-racism and allyship initiative was introduced to 250 Year 12 students with a ‘kick off lesson’ where student leaders explained how their initiative had developed, what the lessons would involve and why it was happening. There was time in the introductory lesson for students to complete the pre-intervention survey. In launching the curriculum amongst their Year 12 peers, the students used the following message:

Countering racism is not an easy conversation, but to make a difference in this important area we have designed lessons which aim to introduce Year 12 students to racism reduction strategies based on intercultural connections, recognising harmful stereotypes, racism awareness and behaviour change. In the

4 This article was originally published in the AHISA Independence Journal (VOL 49 NO 1 May 2024)

future, other cohorts at the college may participate in these lessons using the material being piloted in these lessons.

The curriculum we developed was based on student discussion and participation around the core areas of the origins of racism, racism reduction strategies, recognising stereotypes and the role of media in constructions of race. The lessons centred around discussion-based activities which focused on care and respect for both students and teachers. This included people who could have experienced, or could be experiencing, racism. In our preparations, we asked one another many questions including how students can facilitate discussions about race, ensuring that everyone gets involved, while making sure that people of colour do not feel that their voices are undervalued.

We also queried whether teaching students about institutional racism risked demotivating them towards taking action. We were concerned that learning ‘about’ ( or teaching) racism could position it as a topic that happens to people and remove any immediate impetus to act upon it. In the piloting of the curriculum, we also learned that a message is only as good as its communication and our efforts in the initiation phase had inevitable limitations. Taking explicit steps to establish what the curriculum is responding to and what it aims to change will help create direction and purpose for the curriculum in the years ahead.

EXPLORING THE TOPIC THROUGH ACADEMIC LITERATURE

Racism is defined by the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) (2023) as “the process by which systems and policies, actions

and attitudes create inequitable opportunities and outcomes for people based on race”. The AHRC definition identifies how racism “adapts and changes over time” and can flare against different communities at different times; for example, “towards Asian and Asian-Australian people during the COVID-19 pandemic”, which is a relevant context for this article.

The increasing global urgency surrounding topics of racism and prejudice is awakening a drive for advocacy within today’s generation of students (Nardino, n.d.), who may turn to their educational institutions as a pillar for facilitating this change (Teitel, Antón, Etienne, Loyola & Steele, 2021). However, it is necessary to reflect on the inherent complications that appear within schools, as represented through the anti-racist curriculum delivered

5 Pymble Institute

in our article. Generally, the focus on a results-achievement culture in the Australian education system inherently restricts student-led, grassroots initiatives in curriculum (Bonilla-Silva, 2021). The students’ view as recent graduates of school is that educational and assessment practices in Australian schools appear to be dominated by encouraging learners to be dependent on instruction (i.e. to memorise and regurgitate information) which can lead to students focusing on what the issue is, overlooking how the issue came to be and what can be done to address it.

Education can also fail to teach strategies where students successfully monitor their own academic performance and, more broadly, their everyday actions. Priest (2016) observes that when learning about racism in “the complex intercultural context of our increasingly diverse world”, students must develop experience interpreting “the messages they receive from politicians, the media, social media and friends and families about racism and cultural diversity”. This complex task requires cognition, self-management and empathy. Education programs can fall short when teachers and students need to address the dynamic and complex nuances of prejudice in whatever form it appears. Understanding this, whilst acknowledging the difficulties of teaching skills which tackle multi-faceted problems in a formal education system, we believe prejudice reduction education must be a collaborative effort between students and teachers. This gives it a higher chance of engaging students in the process of decolonising their social consciousness and helps students become more cognisant of

their impact on others. On a broad level, it is important for all teachers to include anti-racism education in their practice so they can create safe environments where they and their students can thrive and grow.

School communities are becoming increasingly aware that racism and discrimination “should be considered as a violation towards [students’] wellbeing” because these violations can directly impact learning outcomes and, ultimately, “school success” for student learners (Auld, 2017, p. 149). Students experiencing racism can be impacted in multiple ways. This points to the need for schools to look within to understand their cultures and to involve students themselves in processes of change so that deeper understanding of belonging and exclusion can surface.

Considering ways racism is structured in schools, Behrning, Gilbertz, Gilson and Groevius (2023, p. 3) note that definitions of racism can be “overwhelming” with subcategories of individual, structural and institutional used to describe people’s experiences and contexts. Schools are places where children and young people are grouped, put in classes and teams, lines, rows and grade levels with varying amounts of conscious or unconscious thinking by adults in the school. This means “institutional racism is particularly visible in schools” (Behrning, Gilbertz, Gilson & Groevius, 2023, p. 13) and thus schools are important places for anti-racism measures to be situated.

The longstanding centering of whiteness within the Australian national identity has created inequities within the education system that impact how we approach anti-racism education

today. Uncritically holding a ‘white standard’ in the education system can push teachers to rely on their own, potentially limited, conceptions of multiculturalism as a basis for lessons.

Professional learning can greatly assist teachers to avoid unintentionally bringing white normativity into the classroom. This involves challenging the centrality of whiteness and the ethno-cultural ‘other’ in Australia’s national identity. These positions can derive from a lack of critical engagement with issues of race and limited consciousness of teachers’ own positionality (Priest, Walton, White, Kowal, Fox and Paradies, 2016). This inhibits students and teachers alike from critically engaging in conversations around race and racial prejudice. Issues such as “code-wording’’ or replacing racialised terms with ones relating to culture, class or home environment can reinforce dominant institutions of whiteness by disguising its reproduction and negating opportunities for productive questioning and discussion of systemic racial issues. This is linked to the idea of ‘colour-blindness’, which further oppresses students of colour by ignoring and minimising their racialised experience. The associated idea of ‘colour muteness’ (Pollock, 2004) can also lead educators to silence themselves and students in open discussions about racism.

Research indicates how under equipped educators can be to deliver meaningful anti-racism education. Martin (2022) exposes the gap between educators’ selfidentification as anti-racist, and their ability to engage in actual anti-racist practice, focusing on the issue within

This article was originally published in the AHISA Independence Journal (VOL 49 NO 1 May 2024)

Don’t shoot the messenger

teacher education programs in white, suburban, private institutions in the United States. Castagno (2008) also highlights the need for open recognition and discussion of the structures and institutions of race within schools to enable genuine student learning.

While Castagno’s (2008) data is drawn from an urban school district in Utah, United States, we found her work highly relevant to the Australian context. Understanding of racism in schools can often present the issue as historical or individual, with a lack of education around the structural nature of racism in the contemporary world (Gillborn, 2008). Williams and Parrott (2014), in their review of social work programs in Wales, United Kingdom, found that misplaced beliefs describing an area as “predominantly white” or having a small minority presence, deprived students in these schools of the tools to handle racial diversity. Traditional pedagogical techniques which position the teacher as ‘knowing’ and students as ‘not knowing’ also contribute to the ineffectiveness of existing anti-racism education (Pon, 2007); students must be involved in the process of knowledge construction for meaningful discussion to occur (Martin, 2022).

Our academic partner, Professor Fiona White’s research, was extremely relevant to our situation. In her coauthored paper, ‘You are not born being racist, are you? Discussing racism with primary aged-children’ (Priest, Walton, White, Kowal, Fox and Paradies, 2016), the authors highlight how primary aged children take direction for how they should approach issues surrounding race from the explicit and implicit attitudes of their teachers. This research (Priest

et. al., 2016) found that despite the pivotal role educational institutions play in shaping student perspectives on race, many teachers lack confidence in a critical understanding of race so as to engage students in meaningful and productive conversations around it. Many excerpts from academic literature highlight the need for a more critical, explicit, and structural engagement with race, both in educator programs and in the programs delivered to students. However, in our literature search, we found the majority of this writing focused on schools outside of the Australian context and many were primary school-based. This article points to opportunities for research in Australian secondary schools.

FEELINGS OF VULNERABILITY

Racism is a topical and sensitive subject, leaving a delicate line between education and provoking and producing unintentional harm for students and teachers. As some of the comments in this article indicate, making a commitment to learn how to educate about race, racism and culture opens the door to vulnerabilities. At our school, as with many others, most leaders and teachers are from white AngloSaxon backgrounds, the historically dominant culture in Australian school education systems. The privilege of cultural hegemony can potentially lead to unintentional neglect of perspectives or a lack of acknowledgement for difference in experiences. Isharah reflects on how she felt vulnerable talking about her experiences as a student of colour within the broader school community and Sarah gives a teacher’s perspective:

“Conversations about race and racism never really reached

outside of my friendship circles because I knew that I would have to explain parts of my experiences to other people as opposed to just venting to my friends. Going into teaching the curriculum, I knew that it wouldn’t be hard to convince students of colour who weren’t already talking about these issues, to voice their experiences openly. I was concerned about this because I didn’t want students to feel like I was pressuring them to voice their experiences”.

– lsharah

“As a teacher, I felt vulnerable about my whiteness and I was aware of this. The students were from cultural. geographical and language backgrounds that were different from mine and I was a generation apart. I tried not to hide behind my power as teacher. I aimed to really learn from the students. In our interactions, I was drawing on all my life experiences, travels, education, reading to find the right words and not offend, nor seem ignorant. I was relieved the students treated me as a learning teacher.”

– Sarah

We understood that our project troubled normative schooling conventions of student-teacher hierarchy and curriculum creation, so we used questions and inquiry to help us to critically engage with ideas of prejudice reduction, social awareness education, and student voice. We often found we had more questions than answers:

When it comes to anti-racism and prejudice reduction curriculum, what benefits and limitations could be achieved through opt-in systems of learning, or is this approach

7 Pymble Institute

beyond the roles of schools?

Does it need to be compulsory and for the whole group?

Are the motives and interests of students inevitably realigned and deradicalised upon contact with schools’ reputational concerns?

What is best practice in antiracism education? How would it be delivered when most teachers were not people of colour and had not lived with racist encounters?

How did we know what type of education in this space was needed?

Although we were having success in working together and bringing change in the Year 12 wellbeing program, the project team wondered whether schools were the best place to have antiracism education. But if not schools, then where would this education take place? Considering the racial inequalities that exist within education concerning access, quality of delivery, and learning outcomes, as well as the history of education as a tool of hegemonic oppression, how can schools facilitate meaningful discussion and change in areas such as race?

STUDENT VOICE AS PROVOCATIVE AND POWERFUL

The project team eventually became known as the Anti-Racism and Allyship Group and it positioned the students as thought leaders, expert presenters and curriculum developers, which are roles of power and influence in a school, and roles usually assumed by adults. Operating as an unofficial, but recognised,

student leadership group, the group also engaged in conversation with other individuals or groups tackling anti-discrimination issues who gravitated towards them. The student group was by no means the only portion of the school addressing issues around race.

Notably, the group was an organically created group, rather than one formed by students holding official leadership positions. Its organic development made it possible for conversations to evolve into learning and teaching experiences which could be used in the evolving curriculum. It didn’t have as its primary function a reporting or consulting nature which might occur with an official school group with responsibility for countering racism and prejudice. Instead, conversations were more genuinely dialogic and coalitional and the role of the messenger within the school was welcomed as a bringer of information and ideas, rather than something to be feared or avoided.

The idea of working ‘within’ is emphasised here as the project was not just developed in the physical and social environment of the school, nor simply in consultation with members of the school community. The student leaders aimed to emphasise through the process of working with peers, teachers and experts that student to student dialogue can be embedded in the curriculum. It is also possible that schools need not function solely as regulating bodies, mediating exchanges between teachers teaching and students being taught. The evolving project was situationally adapted to be highly responsive to the concerns of the school community; it took input and

feedback from students, teachers, wellbeing leaders and executive staff, and gave many people opportunities to both teach and learn.

Importantly, the project provided professional learning for teachers which was designed by the student group. This included online workshops for all staff co-facilitated by the project group and specific training for Year 12 wellbeing teachers who would co-lead the lessons. The online workshops gave voice to teachers’ own experiences of racism and prejudice, anecdotes of living in different countries and places, and to teachers’ affirmations of why the students’ work was worthwhile. The opportunity to be trained in an area that was new and challenging by students who would otherwise be on the receiving end of curriculum was transformative for both students and staff. In these sessions, the student group also advocated for student interests around issues of racial discrimination, such as through students’ nonAnglicised names, and they directly asked staff to consider how staff and students could be more conscious of racial issues and biases.

In schools, teachers frequently engage with students around ‘student voice’ and student-initiated projects but the reality is that schools are busy environments and time and space to add to the curriculum is limited. Our project gave us and our peers and colleagues a taste of what happens when teachers embark on deep listening and take steps to genuinely hear what students are saying. This can be confrontational as students’ ideas and requests can present a challenge and potentially alter planning already underway.

8 This article was originally published in the AHISA Independence Journal (VOL 49 NO 1 May 2024)

Don’t shoot the messenger

We acknowledge that venturing into areas of racism, anti-racism, curriculum development, personal stories, emotions and change making is not easy, but before we realised how challenging it was, we were already in the midst of it and knew we needed to keep going.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Our experience together shows that being ‘ok’ with not knowing ‘everything’ within the enormous field of prejudice reduction and antiracism gives students and teachers an opportunity to ‘do something’ through working together to educate about racism. It is now more than a year since the curriculum we initially

References

devised was concluded, delivered and researched. Sarah and colleagues have since delivered the curriculum to another year group and Faye, Fiona and Isharah have moved into university studies and learnt many more things which are shaping their world view. Fiona offers the final word as she reflects that constructing this curriculum was “a boulder of a challenge and a delicate line between educating and empathising”.

Using student voice to create an initiative that we deemed urgent was only possible through platforms that educational institutions Like ours could provide. It is

inspiring for us to know that the project is being carried forth to subsequent year groups.even a year out from its creation. There were flawed aspects to the original curriculum that I hoped to change, but couldn’t due to it being out of our hands, so discovering that the curriculum was a catalyst for brave students to step forward and improve what we started was a relief. I hope that future Pymble students will continue to contribute and engage with the Lessons, updating them on our behalf with equal amounts of passion or more.

– Fiona

Auld, G. (2017). Is there a case for mandatory reporting of racism in schools? The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 47(2), 146–157. DOI: 10.1017/jie.2017.19

Australian Human Rights Commission. (2023). What is racism? https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/race-discrimination/what-racism

Behrning, K., Gilbertz, L., Gilson, B., & Groevius, R. (2023). Racism. An introduction. (pp. 1-50). In Racism in schools: History, explanations, impact, and intervention approaches. M. Böhmer & G. Steffgen (Eds.). https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-658-40709-4

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2021). What makes systemic racism systemic? Sociological Inquiry, 91(3), 513–533. https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12420

Castagno, A. (2008). ‘I Don’t Want to Hear That!’ Legitimating whiteness through silence in schools. Anthropology and Educational Quarterly. 39:3, 314-333, DOI: 10.1111/j.1548-1492.2008.00024.x

Gillborn, D. (2008). Racism and Education. Coincidence or Conspiracy?, (1st ed.) Routledge.

2 Karabelas, J. Woodward, J., Foley, E., & Ozies, C. (2021). The school that tried to end racism. [Documentary series]: Screentime Pty Ltd.

1 Lodge, C. (2005). From hearing voices to engaging students in dialogue: Problematising student participation in school improvement, Journal of Educational Change, 6, 125-146.

Martin, J. L. (2022). Racial animus in teacher education: Uncovering the hidden racism behind the concept of “dare”. The Educational Forum, 86:3, 253-265, DOI: 10.1080/00131725.2021.2014004

Nardino, M. (not dated). 10 young racial justice advocates you should know. https://www.dosomething.org/us/articles/10-racial-justice-activistsyou-should-know

Pollock, M. (2005). Colormute: Race talk dilemmas in an American school (1st ed.) Princeton University Press. Pon, G. (2007). A labour of love or of response? Anti-racism education and responsibility. Canadian Social Work Review, 24(2), 141-153, https:// www.jstor.org/stable/41669871

Priest, N. (2016). How do you talk to kids about racism? https://theconversation.com/how-do-you-talk-to-kids-about-racism-68160 Priest, N., Walton, J., White, F., Kowal, E., Fox, B., & Paradies, Y. (2016) ‘You are not born being racist, are you?’ Discussing racism with primary aged-children. Race, Ethnicity and Education, 19(4), 808-834, DOI: 10.1080/13613324.2014.946496

Teitel, L., Antón, M., Etienne, S., Loyola, E., & Steele, A. (2021). Practical tools for improving equity and dismantling racism in schools. The Learning Professional, 42(3), 33-39.

http://ezproxy.lib.uts.edu.au/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.uts.edu.au/scholarly-journals/practical-tools-improving-equitydismantling/docview/2545666051/se-2

3 White, F.A., & Abu-Rayya, H.M. (2012). A dual identity-electronic contact (DIEC) experiment promoting short- and long-term intergroup harmony. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48, 597-608.

Williams, C., & Parrott, L. (2014). Anti-racism and predominantly “white areas”: Local and national referents in the search for race equality in social work education. The British Journal of Social Work, 44(2), 290–309. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcs113

9 Pymble Institute

10 This article was originally published in the AHISA Independence Journal (VOL 49 NO 1 May 2024) pymblelc.nsw.edu.au Avon Road Pymble NSW 2073 PO Box 136 North Ryde BC NSW 1670 Australia +61 2 9855 7799 A SCHOOL OF THE UNITING CHURCH ACN 645 100 670 | CRICOS 03288K