34 minute read

KICKING THE CAN BY RYAN PITKIN

NEWS & OPINION FEATURE provides no relief for housing or utility payments as we enter the fall and winter months and as the property owner to be considered protected under the moratorium. Tenants must sign off that they evictions that is this broad and this all-encompassing. It does seem like an extraordinary move by the pandemic and economic downturn continue to meet all of the following requirements: income is federal government,” Sturgill said. “There’s a lot of KICKING THE CAN bring unprecedented hardship to North Carolina families.” HB 1105, known also as Coronavirus Relief Act less than $99,000, did not have to pay income tax in 2019, and/or received a stimulus check; unable to pay rent due to income loss or extraordinary outhope for tenants who are facing eviction but also a lot of logistically trying to scramble to figure out, how is this going to work? How are these protections Why advocates say the federal eviction moratorium 3.0, passed through the N.C. House and, at the time of publication, is expected to be signed by Gov. Roy Cooper. It does not include any new funding for of-pocket medical expenses; and would become homeless or need to double-up (stay with friends or family) if evicted. going to work for everybody?” Some parts of the moratorium leave room for legal subjectivity, such as the question around isn’t enough rental or utility assistance, instead placing funds Tenants must also promise under oath in the people who live in hotels. In August, Queen City previously dedicated to such in a larger pool with a affidavit that they will continue to make partial Nerve spoke with Ethiopia Williams, who has lived BY RYAN PITKIN range of possible uses, according to NC Policy Watch. payments using their “best efforts” to do so “as the in a hotel with her 9-year-old daughter for two years House Bill 1200, which was filed in May and has individual’s circumstances may permit, taking into after an eviction on her record made it hard for her

A new moratorium on evictions went into effect been languishing in committee since, would provide account other non-discretionary expenses.” to find housing despite working multiple jobs. nationwide on Friday, Sept. 4, and will last through $400 million to residents who have been impacted A tenant needs only to print out the affidavit, Sturgill pointed out that the order applies to December, but some local activists say without most by the COVID-19 crisis. which can be found in the moratorium order itself, renters on any residential property, house, building, financial relief to help renters apartment, mobile home, or land climb out of the hole caused by the that’s been rented. However, COVID-19 pandemic, a moratorium what’s in the cards for people who is not enough. live permanently in hotels?

Housing rights activists with “The order does state that the Tenant Organizing Resource if you’re a ‘seasonal tenant’ or a Center (TORC) delivered their own guest at a hotel, this does not eviction notices to members of the protect you,” Sturgill said, “but North Carolina General Assembly families that live in hotels as their (NCGA) on Sept. 3, as community permanent residence may have members spoke about their own an argument that this does still experiences with eviction and apply.” protested the NCGA’s ongoing Sturgill said his team is failure to provide adequate relief working to clear up legal questions during the biggest eviction crisis like that and provide more in U.S. history. The previous day, information, including the order the group rallied in front of the itself and the affidavit needed Mecklenburg County Courthouse for tenants who want to claim its for the same cause. protections, on the Legal Aid of NC

A statewide moratorium on website. evictions began in March and In the meantime, local ended on June 20. In Mecklenburg activists will continue to push for County, eviction proceedings, more relief on the ground for those known as summary ejectment affected most directly by the rent hearings, resumed in July 20. HOUSING ADVOCATES OUTSIDE OF THE N.C. STATE LEGISLATIVE BUILDING ON SEPT. 3. PHOTO BY JESSICA MORENO/TORC shortfall. The new order does not offer Apryl Lewis, a Charlotteretroactive protections to people who have been However temporarily, the moratorium on then sign and deliver it to their landlord or property based housing advocate who spent much of 2019 evicted between the end of the first moratorium evictions will surely help many people who were owner. Landlords do not need to formally accept helping families being displaced from the Lake and the beginning of the next one, which is being at urgent risk of becoming homeless in September the affidavit, tenants only need to be able to show Arbor apartment complex in west Charlotte, helped enacted by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). It’s and the coming months. Isaac Sturgill, managing that they have attempted to deliver it. Sturgill organize Thursday’s protest in Raleigh and explained estimated that 542,000 renter households in North attorney with Legal Aid of North Carolina’s Housing recommended that any tenant who files an affidavit why in a release leading up to the action. Carolina are experiencing a rent shortfall. Practice Group, held a virtual press conference on make two copies, so as to have one for their own “We have been fighting eviction and the

“The recently announced nationwide eviction Sept. 2 laying out the steps for tenants to apply for records. cycle of displacement our community faces daily moratorium by the CDC still leaves many people protections under the new moratorium. Sturgill said he was “floored” by the moratorium, before the pandemic and will continue to fight for vulnerable and does nothing to address the financial The moratorium does not automatically apply which was handed down by the CDC on Sept. 1, and our community during and after,” Lewis stated. cliff that renters and landlords will find themselves to all evictions, only those caused directly by the has not seen anything like it in his eight-year legal “Displacement is state violence.” facing at the end of the year when the moratorium COVID-19 pandemic. Tenants who meet certain career representing tenants. expires,” read a press release from TORC. “[House requirements must file an affidavit with their “In my lifetime I have not seen a moratorium on INFO@QCNERVE.COM Bill] 1105, which just passed in the N.C. Senate,

THAT SACRED SOUND New book and exhibit celebrate the genius of Freeman Vines

BY PAT MORAN

For nearly 50 years, Freeman Vines has carved guitars out of all sorts of wood, including the steps of an old tobacco barn and the soundboard of a dissembled Steinway piano. But in 2015, the unsuspecting African-American luthier, sculptor and mystic bought some wood that would go on to change the rest of his life.

Vines remembers that he went to purchase the wood from an old man demolishing a building down the road from Vines’ shop in his hometown of Fountain, North Carolina.

“He said, ‘You might not want to take that wood. A man were hung on that tree,’” Freeman recalls to Queen City Nerve.

Days later, Timothy Duffy, founder of the Music Maker Relief Foundation (MMRF) and a worldrenowned photographer with work in the National Gallery of Art, the New Orleans Museum of Art and Northwestern University, among other galleries and museums, visited Vines for the first time.

“[Vines] pointed out some planks of wood to me and said, ‘That comes from the hanging tree, and I am making a hanging-tree guitar,’” Duffy says. “Being in the music business and trying to promote things, that title went straight to my brain.”

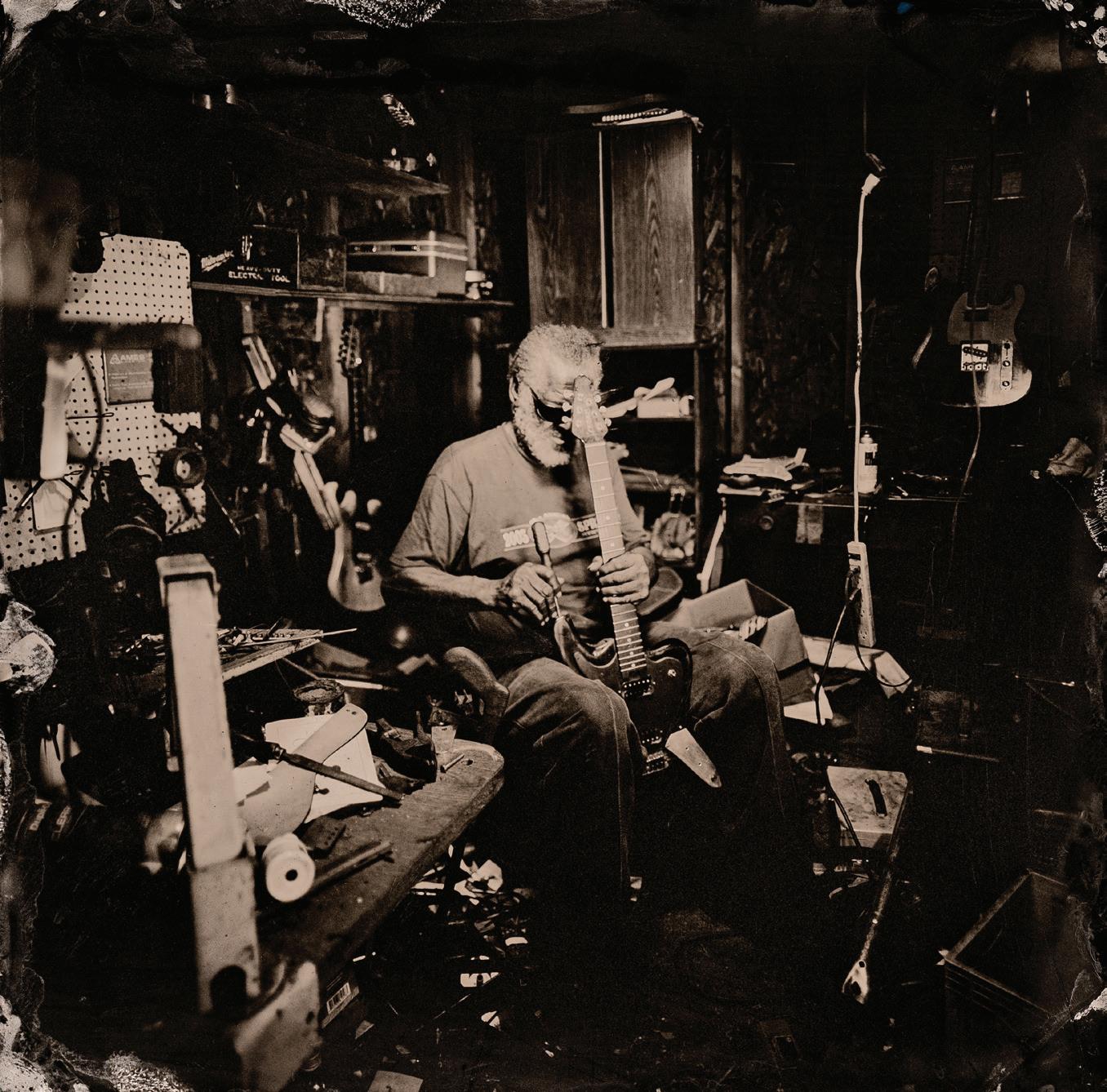

Before crafting that guitar, Vines couldn’t have guessed how it would catapult his life in a whole new direction. Last June, he opened his first solo exhibit at the Greenville Museum of Art, less than 25 miles from his birthplace in eastern North Carolina. Vines, his spiritual philosophy and his art are also the subject of a sumptuous book, published by The Bitter Southerner in association with MMRF. will steal it or destroy it, Duffy says. Featuring text by Vines and folklorist Zoe Van The sculptor, who plied his trade as a blues Buren, and illustrated with Duffy’s evocative and guitarist before turning to guitar-making, has mysterious tintype images, the volume dropped steadfastly refused to sell any of his guitars, chasing on Sept. 1. The exhibit and the book share a title: prospective collectors away. But he showed them Hanging Tree Guitars. to Duffy that day because Duffy had come to photograph Vines’ handiwork with a process as

Hidden in plain sight traditional and hand-crafted as Vines’ approach to

But all that was five years in the future when building guitars: the collodion wet plate process, Duffy stepped into Vines’ yard for the first time in used to create tintypes. 2015. He knew at once that he was in an artist’s “You have to mix the chemicals yourself,” Duffy space. says of tintype making. “You have to cut the tin and

The Southern yard, especially in an Africanfiddle with the camera. In any part of the process American community, is a sacred spot, Duffy offers, you can totally screw up.” a space where a person can express themselves The result of juxtaposing Duffy’s familiar yet and reflect their personality. At the same time an otherworldly images with Vines’ words is magical, Duffy says, and can be seen in Hanging Tree Guitars. Duffy feels the book’s layout and design allowed him to chase Vines’ ideas. On that very first visit, which would be the starting point for a close friendship and partnership, Vines showed Duffy the two planks of black walnut wood, all that was left of the lynching tree where a Black man named Oliver Moore was purportedly murdered 90 years ago. Duffy remembers going into Vines’ shop. On a manila envelope Duffy found a drawing Vines had FREEMAN VINES WORKS IN HIS WORKSHOP, 2017 made. It pictured a PHOTO BY TIMOTHY DUFFY tree with a rope and African-American artist also has to keep his work it. It was the earliest vision for what would become invisible to the white community. Otherwise whites Hanging Tree Guitars. a guitar hanging from

“Freeman started pulling guitars out of piles in The unseen world his yard under linoleum,” Duffy remembers. “He was Vines remembers that the sound shot through hiding all his prized possessions in plain sight.” him like an electric shock. He was leaving his shop

Dozens of rough-hewn yet elegant guitars, late one evening when it struck like lightning in myriad and fantastic shapes, unpainted and and nearly drove him crazy. Vines says he’s been showing their wood grain, were on the property. searching for that sound ever since, trying to capture The guitars’ pickups had also been fashioned by it in many of the guitars he made. So far, it’s eluded Vines out of old radio parts. him.

But he has found the spirit within wood.

“The thing about wood is, wood has a soul,” Vines says. “The hanging tree wood, that gave me a feeling I never experienced.”

In a conversation with Dr. Ndubuisi Ezeluomba, Curator of African Art at the New Orleans Museum of Art, Vines went into more detail.

“[The wood] had all that stuff in there,” Vines said. “It sounded kind of strange when I hooked it up with pickups, so I left it alone.”

Not every piece of wood that comes into Vines’ hands becomes a guitar, the sculptor told Dr. Ezeluomba. He told of another piece of wood, much vaunted by its seller for its superior vibrations. Vines had hoped to find his elusive sound with it, but in disappointment he turned the wood into a guitar where the body resembles a mask.

The mask-guitar led Dr. Ezeluomba to compare Vines’ sculpture, including his guitars, to traditional African masks, and not just because the aesthetics are similar.

“I see you as a vessel,” Dr. Ezeluomba said to Vines. “You are the process through which spirit manifests itself,” likening Vines to the African maskmakers who are also conduits for forces from an unseen world.

Vines is no stranger to that unseen world, with interests ranging from the pagan religion Wicca to 19th-century occultist Madam Helena Blavatsky, founder of Theosophy, an amalgam of Western esoteric beliefs and Eastern religions. In the Theosophical view, space is not only boundless, it also contains of a number of unperceived dimensions. It’s a concept not unlike the multiverse posited by physicists.

“There are dimensions that are as real as this one,” Vines tells Queen City Nerve. He offers that it’s easy to get out to those dimensions, but not so easy getting back to ours.

“I know the proper incantations, the [magic] circles and going to the trees,” he elaborates.

Vines also speaks of meditation. “[You can] keep on going deeper and deeper until you realize that having an OOB, an out-of-body experience. And that’s when it gets dangerous.”

Duffy says the guitar maker is a voracious reader, recently racing through the epic medieval AngloSaxon poem Beowulf for fun.

“Who reads Beowulf for fun?” Duffy asks. “He’s got me reading The Egyptian Book of the Dead, so I can understand what he’s talking about.”

Duffy says Vines has taught him the spiritual nature of things, which may be why he takes it seriously when Vines feels power in the hanging tree wood.

“[Vines] talked to me about how the blood of the fellow that was lynched was coming into him in his dreams and thoughts,” Duffy says. “It was obvious to him that the wood spoke to him.”

Confronting racial terror

The lynching took place in 1930 on Aspen Church Grove Road, close to where Wilson and Edgecombe counties meet, but the hanging tree is long gone.

It was a particularly brutal lynching, Duffy says. The white men put a mule harness under Moore’s armpits and suspended him from the tree. Then they shot him 200 times.

According to folklore around Fountain, the bullet casings were so heavy on the street, the postman couldn’t deliver the mail.

Afterwards, the vigilantes left guns on a card table under the tree so anyone else could drive up and shoot the carcass.

Folklore or not, Duffy says the story taught him the realities of racial terror.

“I learned how a society can terrorize a people. They do [acts of terror] every once in a while, so everyone knows their place,” he says.

Vines has encountered that terror for most of his life.

Born in 1942 in rural Greene County, he grew up on a white man’s farm in Snow Hill. Both Vines and his mother worked for the owner.

“My mother was a house woman. I know you know what that is,” he says flatly. “She was a house nigger.”

Vines went to jail for the first time at age 14. For what, he will not say. In 1964, at 22, he and some white men got caught with two 500-gallon moonshine stills, Duffy says. The white guys walked, but Vines did time in the federal penitentiary system.

He spent a total of five years, first in Atlanta and then in Tallahassee, Florida, with a ball and chain attached to his leg. He still bears the scars.

Though Vines learned to read and write in the penitentiary, in Hanging Tree Guitars he’s emphatic about the nature of his incarceration.

“The college I went to is spelled C-H-A-I-N G-AN-G.”

“Freeman has suffered deeply and painfully,” Duffy says.

At the same time, Duffy believes Vines’ body of work, which includes all his guitars, is a statement on how to address racial terror.

“It’s art of resistance,” Duffy says. Although a code of silence remains in small towns throughout the Carolinas, it will only change when voices like Vines’ are heard, Duffy believes.

And lately Vines’ voice has grown louder. Some of his work was part of We Will Walk — Art and Resistance in the American South, a group show at the Turner Contemporary art gallery in the United Kingdom last February.

In June, Vines’ debut solo exhibition went up in his home community at the Greenville Museum of Art. The exhibit, which engages memory, racial identity, and spirituality — themes that thread through all of Vines’ work — is open to groups of 10 or less by reservation, and boasts a steady stream of visitors, Duffy says.

Let the music lead you

For Duffy, his visit to Vines’ home in 2015 was an unexpected result of a passion that took hold when he was 16 years old. At that early age, an interest in ethnomusicology spurred him to start recording and photographing traditional folk, gospel and blues artists throughout the South.

After studying music in Mombasa, Kenya, Duffy was introduced to Piedmont blues while earning a master’s degree in Folklore at UNC Chapel Hill.

“All the people I worked with had the greatest talent but were really poor,” Duffy says. Realizing that there was little space for traditional artists in a fame-obsessed music industry, he determined to set up a sustainability program for traditional artists.

“They’re the cultural wellspring of America’s greatest export, our music,” Duffy offers.

He also feels that eastern North Carolina has been overlooked in the narrative about American music. Those who point to Mississippi as the birthplace of the blues and New Orleans as the cradle of jazz are forgetting our history, Duffy maintains.

In the colonial South, more than half of all the enslaved people that were brought to this country came through the eastern Carolinas and the Piedmont, Duffy asserts.

“This is where the first people were enslaved and this is where African-American music was first created.”

In 1994, Duffy launched Music Maker Relief Foundation along with his wife Denise. The nonprofit takes a people-first approach, Duffy explains, preserving the traditional music of the South by supporting the musicians who make it. The foundation focuses on sustenance, education and performance.

“This work is real social equity,” Duffy says.

Tour support is one of three tent poles for MMRF’s sustenance approach. Many traditional musicians are too poor to tour, Duffy offers. So, the organization acts like a small bank, paying for airplane tickets, meals and hotel rooms for artists who’ve never owned a credit card, then collecting on its micro-loan after the tour has made a profit.

The foundation also focuses on education, releasing books like Hanging Tree Guitars, and mounting exhibits like the one at Greenville Museum of Art to let people know about artists like Vines, Lightnin’ Wells, Pinetop Perkins, Johnny Ray Daniels and others.

Several of these artists perform on a full-length album, released in tandem with the Hanging Trees Guitars book, with which it shares its title. On the collection, Daniels plays a guitar carved and crafted by Vines on the song “Somewhere to Lay My Head.”

MMRF also provides musicians with sustenance, Duffy says, offering basic aid for artists living in chronic poverty. When people are living on just a few hundred dollars a month, receiving aid for food and home repair is a big deal, Duffy offers.

“We’ve bought homes for people that were homeless,” he says.

The nonprofit helped Vines pay for doctors’ bills and medications to get his diabetes under control. The foundation also bought an old drugstore in Fountain, converting it into an art studio for the

FIELD OF GUITARS, 2017 PHOTO BY TIMOTHY DUFFY

sculptor and guitar maker.

Shot through with sound

For all the work MMRF has done, Hanging Tree Guitars and giving Vines’ art and philosophy its broadest forum yet is perhaps the most important, Duffy says. “I think the book is a jewel,” he says. “It’s the greatest thing Music Maker has been a part of.” In the book, Vines talks about racial terror and how it effects an artist and a community, and although Vines has been terrorized, he comes through it to a place of beauty and love. Hanging Tree Guitars also examines the mystery of a parallel universe, Duffy says. Vines’ story offers an examination of the other side and the unseen world, told by someone who has studied it extensively.

As Dr. Ezeluomba suggests, that other side could be, in part, the source of Vines’ genius.

But with that gift, the ability to be a vessel, comes the responsibility to share that transmission from spirit.

Vines suggests that he’s often unable to control or shut off the transmission, and that consequently he’ll never stop trying to replicate it in the material world.

When asked about what message he’d like his life’s work to convey, Vines returns to the night he received an unexpected blessing that also almost drove him mad.

“It’s the sound,” Vines says. “Like the howling of a dog in the middle of the night, it’s the sound.”

ARTS FEATURE Beautiful Like Chai Amarra Ghani is the thoughtful leader of community that we can all be proud to call home. “Welcome Home Charlotte,” a group that was formed A WARM WELCOME to help resettlement and relief efforts for local refugees. Follow them on Instagram @welcomehomeclt. Stories of humanity from our immigrant neighbors Growing up in a household with Pakistani parents while living in the United States, I navigated two worlds. It’s a delicate dance that most children of immigrants learn early. BY HANNAH HASAN In our home, my parents only spoke our language. So when I went to elementary school,

The following is part of a new project in which I was required to take ESL classes for the first few Hannah Hasan adapts her ongoing Muddy Turtle Talks years. While at school, I wore the American spoken-word storytelling event series for the pages of clothes; jeans and t-shirts. As soon as I got Queen City Nerve. Visit facebook.com/epochtribe to home, I would change into my Pakistani learn more and check for upcoming events. clothes.

Here’s the thing. I know — or know of — so identity while in the outside world, it was many amazing people in our community who make about learning to navigate both worlds while important and beautiful contributions to this place holding on to the language and traditions that that we call home. shaped the woman I was to become.

While I’ve had the chance to get to know some I can acknowledge the imperfect parts of them on a more intimate level, it’s not lost on of my Pakistani me that I only know culture that also most of them through exist within the their work: their art, greater American the programs and culture. Colorism. events they create, It’s a very real the organizations they problem. I was manage. in my early 20s when

Yes, these people’s I was inside of a work is a snapshot of coffee shop and had who they are, but it’s a moment that I have not all that they are. never forgotten.

These people who I ordered chai. As make extraordinary I went to pour the tea contributions to our city and our world are full human beings with AMARRA GHANI PHOTO COURTESY OF EPOCH TRIBE into the cup, I marveled at the beauty of the color of the chai. “Wow! stories and experiences, and those stories and What an amazing hue. That is such a vibrant and rich experiences directly correlate with the way that they color that this tea has created.” I was immediately show up in the world. overwhelmed. It was the same as the very unique

Welcoming Week 2020, held between Sept. color of my skin. 12-20, is a national celebration of immigrants and It was an overwhelming moment for me. I went their contributions to the fabric of American society. into the bathroom and wept in the mirror. My skin To ring that celebration in, I decided to interview is special and beautiful and it carries the traditions some amazingly diverse Charlotteans who work to and sacrifices and the love and history of my parents lift others in our community and write stories from and their parents. It tells the stories of my family and the experiences that they shared with me. my people. It deserves to be honored and cared for.

Through storytelling, we can get to know the I deserve to be honored and cared for. Who knew stories of Charlotteans with immigrant roots who something as small as a cup of chai could teach me a are using their experiences to create the kind of lesson as big as self-love and acceptance?. It wasn’t about erasing my Pakistani

A Language Of Our Own

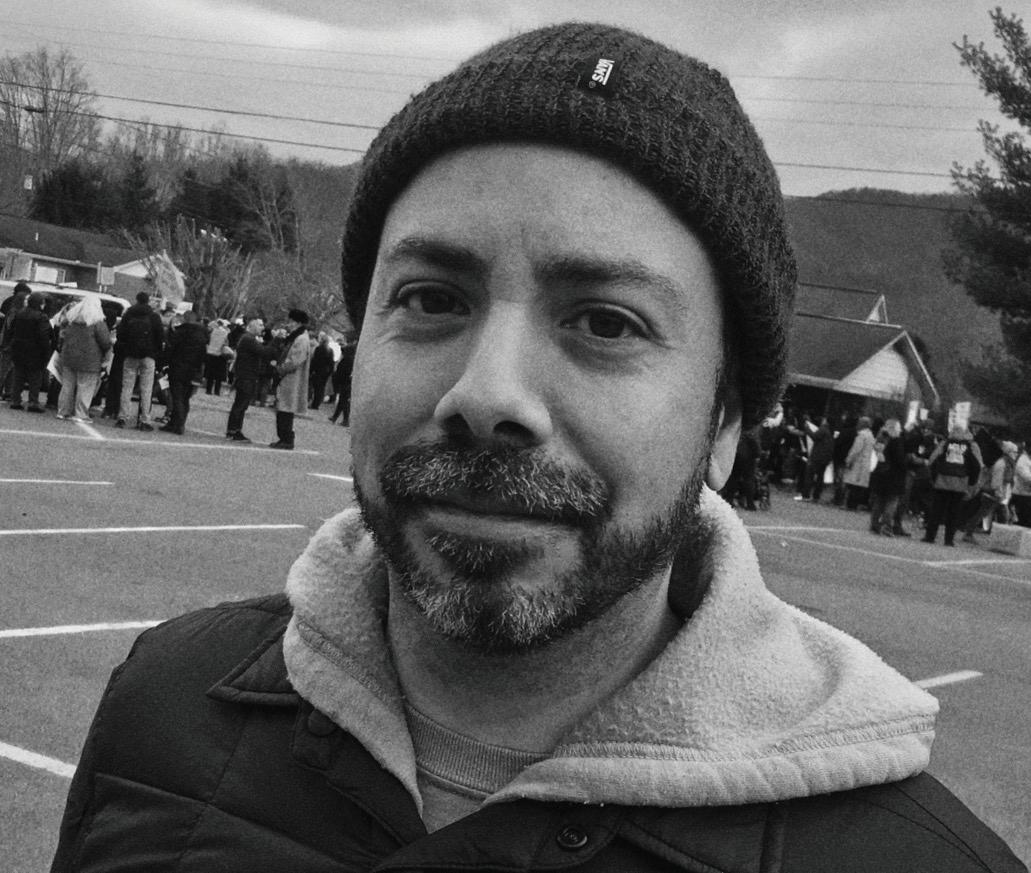

Hector Vaca Cruz is an organizer and photographer and is currently featured in the Levine Museum of The New South’s Counting Up Exhibit. Check out Hector’s work by following him on Instagram @ hectorvacacruz.

My mom is Puerto Rican. My dad was Ecuadorian. After we moved from New York, they raised our family here in the South. Much of who I am is deeply rooted in the lessons and traditions that I embraced from my mom and my dad and their background.

HECTOR VACA CRUZ

PHOTO COURTESY OF EPOCH TRIBE

The biggest similarity in their respective cultures was that they both speak Spanish. But Ecuadorian culture is mostly Spanish and Native Indigenous people with some African influences.

Puerto Rican culture is really a blend of Spanish, African, and Tajino natives. As for me, I grew up identifying with both Puerto Rican and Ecuadorian with roots in New York. By college, I started to explain it as Equo-NewYorican.

A huge portion of my identity is connected to my language. I grew up more Puerto Rican. I spent summers there when I was younger. The Puerto Rican side was more familiar with the ways that they spoke Spanish. These family members were louder and more gregarious. It was more lighthearted on that side.

The Ecuadorian side of my family is more formal in the way they speak their Spanish. I was taught on that side to enunciate all of my words and to use better grammar. Even dinner was more formal on that side. You sit. You eat. “You have one mouth, you can’t do both.”

At some point, my parents developed a neutral accent between the two of them. My mom came a little over to the Ecuadorian side and my dad shifted a bit to the Puerto Rican side. So within my household, we spoke our own language that was a combination of both.

Our mixed accent has been difficult for others to understand, and that’s OK because through developing our own family language we have built a connection that is unique to us and our story.

Writing Home

Kurma Murrain is a published poet and educator. Find her bilingual book In the Prism of Your Soul for

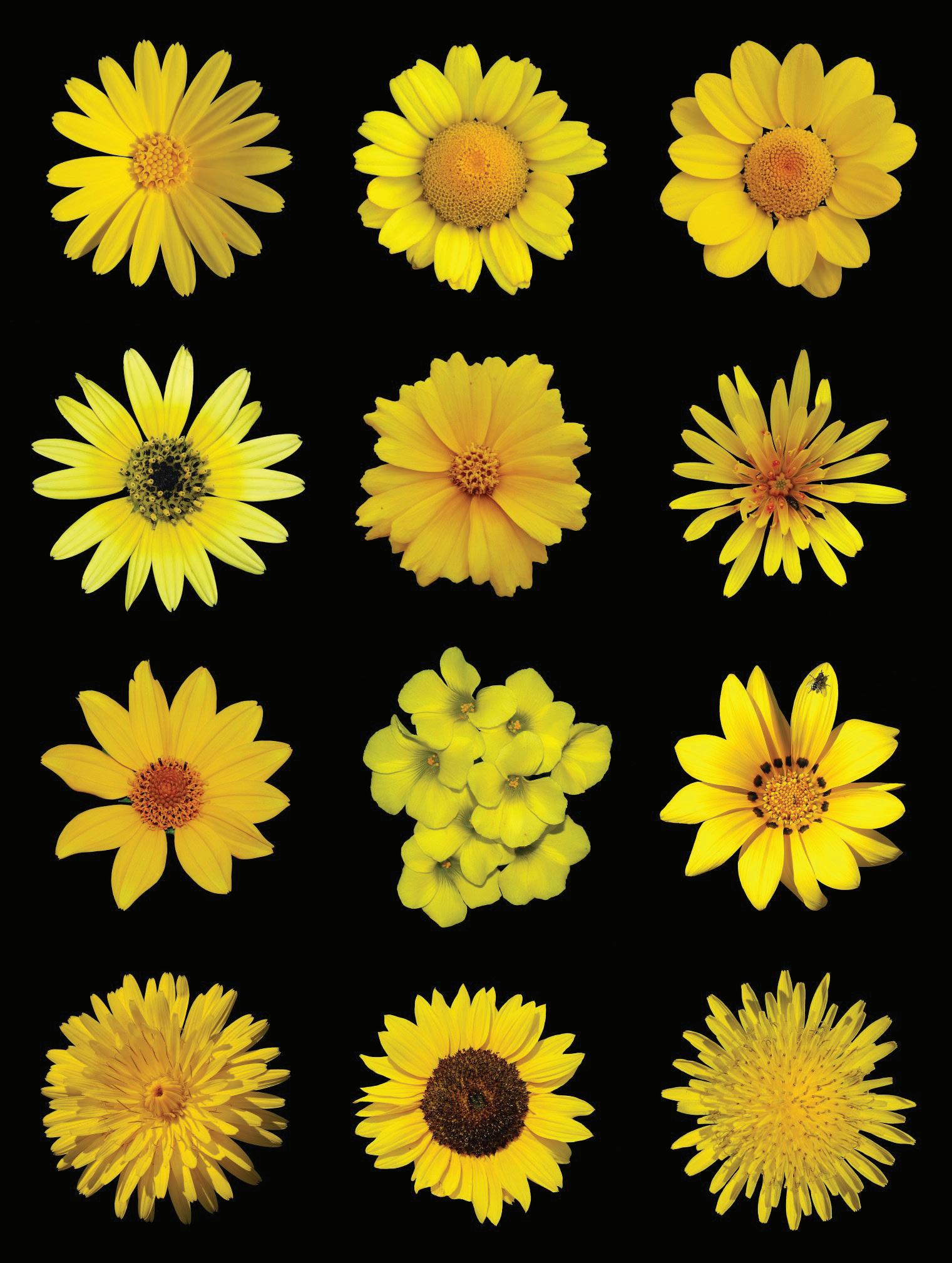

sale on Amazon. I have my beautiful mother to thank for my love of poetry. She was an amazing woman who wasn’t afraid to be different. She was a mantissa (mixed-race) woman married to a Black man living and raising children in the mountainous city of Bogotá, Colombia, in South America. When I think about my love for words when they come together to tell a story in a melodious way, I think about my mother reading the works of Chilean poet, diplomat and educator Gabriela Mistral to me. Her work sounded very musical, and it reminded me of the freedom that poetry has. I was a young girl, but I started writing then. I would write to my friends. My friends would ask me to write letters for their boyfriends and girlfriends. I was famous for that.

I fell “in love” when I was 12. I wrote a very emotionally vulnerable poem. My mother asked, “What happened with this boy?” I explained that I didn’t know. It was just in my head. He didn’t know.

The relationship wasn’t that deep, but I understood how to capture feelings in this unique and poetic way. I learned that at a young age.

When I moved to the United States for a teaching opportunity in the ’90s, I was afraid that Charlotte would feel like a small town, and that there wouldn’t be much to do here, and that I would be so far away from my home. But I was pleasantly surprised when I got here, and I’ve been able to continue to do things that I love, like write poetry.

I think in English now. I haven’t written much poetry in Spanish but the memories — the owers, the elds, the mountains, the food — will always be in my writing.

Colombia will always be in my writing. A greater extension of that is that somehow my mother always comes to my poems. I mention the word mother often in my poetry. It just comes. I can’t avoid it.

Since my mother is synonymous with home, I always carry her with me. Wherever I am in the world, as long as I have my poetry, I will always have my home.

Creating Meaning

Liliya Zalevskaya is an artist whose work has been featured in galleries locally and in other cities. Find out more about her work at liliyazalevskaya.com.

LILIYA ZALEVSKAYA

PHOTO COURTESY OF EPOCH TRIBE

I was 13 when my family immigrated from Ukraine to the United States with refugee status. Before we moved to Charlotte, we lived in Philadelphia. I didn’t speak English but luckily in

Philadelphia, they have a large Russian/ Ukrainian community. So when I went to school I just hung out with other Russian kids, which meant there was not a lot of pressure to learn English. My sister was a couple of years older than me and she picked up the language quicker than I did.

When we came to Charlotte, we went to International House and they did placement tests and it was determined that I would need to take ESL classes. I learned English, but there was still some insecurity there. It’s something that a lot of immigrant children experience.

When I was a kid, I was quiet and observant. I wanted to go into theatre, but when we moved here I was so shy about having an accent that I never took any theatre classes. I was fascinated by The Little Prince story books. They are by a French writer who had the idea that certain people, when they grow up, they can still have imagination but some don’t. It has all of these metaphors about looking beneath the surface and nding truth and meaning. This really inspired me and helped to shape my career as an artist.

I like the idea of duality in things and perception is interesting to me. One of the things about growing up in Soviet culture, everyone reads between the lines. People know that whatever you say there is always a hidden meaning and a metaphor. Nothing is always just as it seems. And as a person who has learned to navigate the waters of cultural di erence, I understand that if we search deeply enough we can nd meaning in things and experiences that connect all of us to each other. That is a part of what I try to create in my art.

HomeGoing

Meki Shewangizaw is the vice chair of Tesfa Ethiopia, an organization that helps support the children of Ethiopia. Learn more at tesfaethiopia.org.

My family moved when I was four. We came over on what was called a Diversity Immigrant Visa. It’s kind of a lottery type of process. Every year, my dad would sign up, and every year he didn’t get chosen. People would ask him why he kept trying. He said it doesn’t hurt to try.

On his 10th year, he signed up and he got it. He moved to America and brought me and my siblings and my mom a little later. We grew up in America but we had a very Ethiopian household, and because of that, I’ve always felt at home in immigrant

MEKI SHEWANGIZAW

PHOTO COURTESY OF EPOCH TRIBE communities. I even worked at a refugee agency after college and it was ideal.

I always knew that at some point I would want to go back home, I signed up for a fellowship to go to Ethiopia for six months. It was magical. I stepped o the plane, and the rst thing I thought was, “Wow, everyone looks like me.” And I know that might be strange for some people to understand, but the

United States is very diverse and this is the rst time I go to another country and everyone looks like me. Also, everyone was able to say my name so casually. I didn’t have to shorten it or enunciate to make it t into their mouths. They were able to say my name — as it is — as it was given to me at birth. There was also an instance of community, that was like a familial understanding, a feeling that you have with people that you have never met before. I’ve never felt anything like that. It was a great time for me and my family. It was an experience of a lifetime. It really helped me to understand my parents better, and what home means for me and so many like me. America is home, a familiar place. I grew up here. When I came home from Ethiopia, my dad was cooking food and playing traditional Ethiopian jazz music. I was like, “Ahh, Home.” My physical home is like a little Ethiopia in America. And I love both of them. America is my familiar home,

INFO@QCNERVE.COM

Ethiopia is my spiritual home.

Enjoy a moment of peace on us. www.xcoobee.com

PICKIN’ FOR PROGRESS Che Apalache frontman returns to North Carolina to make a difference

BY PAT MORAN

As a Grammy-nominated bluegrass musician, Joe Troop is no stranger to making some noise himself. But with his new video series Pickin’ for Progress, he’s using his platform to inspire people to tell their stories, providing a megaphone for voices that too often go unheard.

He’s also encouraging people in rural North Carolina to reclaim their power by exercising their right to vote

Stranded in Winston-Salem, a city he left soon after he came out as gay at age 19, Troop launched the Pickin’ series of mini-documentaries mixed with musical performances because he was looking for something to do. Now he may have found a new calling.

“Being able to do this project is a tremendous blessing,” Troop says. “I feel more passionate about this than … anything else I’ve done.”

That’s saying a lot. The 37-year-old banjo player and his band Che Apalache have been praised for revitalizing roots music, by taking the instruments and techniques of Southern stringband music and applying them to the rhythms and textures of Latin, African and Asian music.

Troop puts that glowing portrait in perspective. Che Apalache is a result of the sounds and rhythms of Buenos Aires, the band’s hometown, not any predetermined plan to shake up the bluegrass establishment, he says.

“Everyone wants a mystical origin story,” Troop offers. “It’s just four people living in a city of 15 million people, messing around with different forms of music.”

Troop has lived in the Argentinian capital city for the past 10 years, and his Latin-American bandmates — Mexican banjo player Pau Barjau, and two Argentinians, guitarist Franco Martino and mandolinist Martin Bobrick— are his former music students.

“I had knowledge of the traditions and how we play the instruments. I taught them that,” Troop offers. “They’re cosmopolitan guys who listen to all kinds of music.”

That eclecticism is apparent on the band’s acclaimed 2019 album Rearrange My Heart, which opens with “Saludo Murguero,” a greeting framed as a murga, a Uruguayan street theater tune. The hypnotic “Maria” follows, entwining tango, percussive candombe and the rasgueado rhythms of flamenco.

Che Apalache also draws on folk music’s tradition of protest songs, saving its strongest messages for its most traditional tunes.

“The Dreamer” recounts the story of gay North

JOE TROOP OF CHE APALACHE PHOTO BY AARON GREENHOOD

Carolina resident and DACA recipient Moises Serrano, says Troop. Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipients, or “Dreamers,” are undocumented immigrants brought to the country as children who receive eligibility for a U.S work permit plus a renewable two-year period free from the threat of deportation.

“It’s important to shine light on stories [like Serrano’s] because … the Trump administration has totally upended legal immigration and protections like DACA,” Troop says. “’The Dreamer’ is a song that hopes to humanize these dreamers and give them a voice.”

In January, when he attended the Grammy ceremony where Che Apalache was nominated for Best Folk Album, Troop walked the red carpet with Serrano

“The Wall” is another traditional tune that subverts bluegrass expectations with a progressive message, criticizing Trump’s wall, and the racist pandering it represents.

“[Bluegrass] has become a stomping ground for white nationalists.” Troop says. “They think this is their music. It’s not.”

Troop points to Southern string-band music, some of it historically played by African Americans, to refute the narrative that bluegrass is based entirely on the music of white Appalachian communities. He also calls attention to the instrument he plays. “It’s an African instrument,” Troop says. The bluegrass establishment’s focus on straight white male players is one the biggest things that alienated Troop when he was growing up queer in Winston-Salem. “White people in the United States over-compensate for the fragility of our own identities, which are rooted in inflicting hardship upon others and appropriating and fetishizing their cultures,” Troop maintains. “I’m a part of that and I recognize it.” Troop dealt with his alienation by leaving, heading off to college at UNC Chapel Hill, and then to Spain at the University of Seville. Travel seemed to set off a globetrotting chain reaction for Troop. In addition to America and Spain, he also lived in Japan before landing in Buenos Aires, where he’s settled for the last decade. Then last March, Che Apalache was touring the U.S., when the country swiftly shut down as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. Overnight, the four members of Che Apalache had to rearrange their lives. The two Argentinians, Martino and Bobrick, booked one of the last flights out of their country to Buenos Aires. Barjau decamped for Mexico, which hadn’t locked down yet. Troop decided to stay in the states to deal with the economic repercussions of an abruptly canceled tour.

As Troop was tying up loose ends, he was contacted by Matt Hildreth of RuralOrganizing.org, a progressive advocacy group that states on its website that its mission is “to rebuild a rural America that is empowered, thriving, and equitable.”

“Matt was challenging the narrative about rural America,” Troop remembers. He says that RuralOrganizing.org, which has been working since last summer on a campaign to strengthen the US Postal Service, challenged Troop to write a song about the service.

The song, “A Plea to the US Government to Fully Fund the Postal Service,” went viral in April, when Troop debuted it online.

It went viral again in August when Troop performed it in front of hundreds of protesters at the Greensboro home of embattled US Postmaster Louis DeJoy.

The following Monday, Troop played the song and a few others at Marshall Park in Charlotte on the first day of the Republican National Convention. In July, RuralOrganizing.org launched VoteNC.org, a coalition of North Carolina grassroots organizations devoted to a varied slate of projects across the state.

VoteNC.org’s goal is to encourage people to volunteer with grassroots organizations to help with a number of causes including getting out the vote, Troop says.

The purpose of the Pickin’ for Progress videos, which can be seen on YouTube and Facebook, is to get people to volunteer for VoteNC.org and pick which organizations they want to work with, Troop offers.

Each episode of the series, hosted by Troop, blends social justice music and interviews with rural progressives in a mini-documentary format. Several of the songs were written by Troop, and he arranges all of the material

Troop kicked off the series with a friend, Oklahoma-born Cherokee Nokosee Fields. In the interview, Troop and Field examine the very notion of immigration in North Carolina, where whites have displaced original indigenous inhabitants.

They also play the tune “Hermano Migrante” (“Brother Migrant”).

Other editions feature interviews with Juana Luz Tobar Ortega an undocumented immigrant who has sought sanctuary in a Greensboro church, and Lumbee activist and environmental scientist Alexis Raeana Jones.

The interviews are followed with performances by Troop. Often, the interview subjects, like Jones, join Troop in song.

At the time of this writing, the latest video, episode 8, covers the exploitation of undocumented central American immigrants, largely indigenous Mayan people from Guatemala, in Morganton.

Pickin’ for Progress is a showcase of progressive thought in North Carolina, Troop says. He counts himself lucky that he gets to sit down with interesting people and help them to tell their stories. “This is the best education I’ve ever gotten,” he says. “I won’t lie, it’s a challenge, [but] it’s a noble challenge. To me, it’s the greatest job, [and] the best work I’ve ever done.”