9 minute read

RETHINKING THE MECK DEC BY PAMELA GRUNDY

NEWS & OPINION FEATURE RETHINKING THE MECK DEC

It’s time to reconsider what’s worth celebrating about May 20

BY PAMELA GRUNDY

A tarnished history

On the morning of May 20, 1963, a group of Johnson C. Smith University students set out on the two-mile trek from the Smith campus to the Mecklenburg County courthouse. Clad in suits and Sunday dresses, and carrying an American flag, they sang and clapped as they made their way downtown.

Civil rights energy was growing nationwide. Just three weeks earlier, police in Birmingham, Alabama, had attacked Black children with fire hoses and police dogs, creating searing images that were broadcast around the country. Martin Luther King Jr. had written his famous Letter from Birmingham Jail, in which he asserted: “We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.”

When the Smith group reached the courthouse steps, leader Reginald Hawkins echoed King’s words. “We want freedom and we want it now,” he proclaimed. “There is no freedom as long as all of us are not free.”

In Charlotte, on May 20, talk of freedom rang with special depth. May 20 was not just any day. It was Meck Dec Day. A long-standing story held that on May 20, 1775, a group of Mecklenburg County leaders signed a document that became known as the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence, becoming the first Americans to officially reject British rule and declare themselves a “free and independent people.”

The Meck Dec has sparked controversy through the years. While Mecklenburg leaders clearly produced a statement called the Mecklenburg Resolves, carried by militia captain James Jack to the Second Continental Congress in the summer of 1775, documentation for the more revolutionary Meck Dec is far less definitive.

But whether myth or reality, the Declaration has been a significant historical force in Charlotte and in North Carolina for nearly two centuries, forming a core component of city and state identity. The date has adorned the state flag since 1861, and is emblazoned on state license plates that proclaim “First in Freedom.”

Promoters of the Meck Dec have generally focused on the signers’ independent spirit, distrust of authority and “firm belief that all men were equal.” Chronicler J.B. Alexander set this tone in 1902, writing that Mecklenburg County “was populated with a race of people” who “had been taught that liberty and independence were necessary to achieve the highest aims in life.”

What Alexander failed to mention, and what most accounts of the Meck Dec either leave out or

gloss over, is that many of the signers were actively engaged in denying liberty and independence to other human beings — the men and women of African descent whom they had personally enslaved. Men such as John Davidson, Thomas Polk and Hezekiah Alexander built fortunes by exploiting enslaved labor. They justified this practice with the claim that Africans and their descendants were a “lesser” race of people than the white Europeans who enslaved them. That belief is as much a part of Charlotte’s history as the ideas expressed in the Declaration. It is time for our community to grapple with that contradiction.

The Meck Dec first received widespread notice in 1819, when Joseph McKnitt Alexander wrote about it for the Raleigh Register. Alexander’s father, John McKnitt Alexander, had told him stories of composing the Declaration and sending it to Philadelphia. While the original manuscript had

burned in a house fire, Alexander explained, his father’s papers contained a re-creation.

Despite questions about the document’s authenticity, Charlotteans soon began to celebrate it as a daring blow for liberty. The ceremonies became increasingly elaborate. An 1857 event began with the sound of “hoarse-throated cannon,” and involved the raising of a 130-foot “liberty-pole,” a lengthy ceremony on a platform “beautifully festooned” with flowers, cedar and holly, and a dinner for several hundred people that started with green turtle soup and ended with toasts to “the earliest and boldest aspiration for freedom in our country’s history.”

In 1861, when North Carolinians were considering whether to join other Southern states in seceding from the Union, delegates to the state convention chose May 20 as the day to decide.

“As soon as the vote was announced,” reported the editors of the Greensboro Patriot, “one hundred guns were fired on Capitol Square, and the bells of the city were rung, amid the shouts of an excited multitude. Thus . . . was the anniversary of the

Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence gloriously celebrated by the delegates of the people.” Convention delegates made the Meck Dec a key component of the new state flag, passing an ordinance that stated the flag should “consist of a red field with a white star in the centre, and with the inscription, above the star, in semi-circular form, of ‘May 20th, 1775,’ and below the star, in semi-circular form, ‘May 20th, 1861.’” After the war, the 1861 date was replaced by the date of another Revolutionary Era document, the Halifax Resolves. But the Meck Dec date stayed, in part because newly emancipated

African Americans found their own use for it.

This became clear in 1867, when Black Charlotte residents chose May 20 as the day to officially enter politics. That morning, Black members of the

Union League of America formed a procession

“at least half a mile in length” that ended at a stage on Tryon Street. Black and white orators

“admonished the whites to lay their prejudices in the grave of slavery,” and urged Blacks to “seek education, lands and money.” The group directly invoked the Meck

Dec, describing May 20 as “hallowed by its associations, and connected to liberty and the political equality of man with his fellow,” and asserting that they stood strong for “the advancement of the races” and for “peace and prosperity for the land of our homes . . under the ample folds of the glorious old full starred American flag!”

Questions of who deserved liberty and equality, however, remained far from settled. The postwar era saw prolonged, often race-based political combat. Control of state government shifted back and forth until 1898, when a vicious white supremacy

LOCAL ARTIST NADIA CHAUHAN REIMAGINED THE CAPT. JACK IMAGERY (NEXT PAGE) IN CONTEMPORARY TERMS.

VISIT QCNERVE.COM FOR NADIA’S ARTIST STATEMENT.

campaign seized statewide power, violently overthrew the elected government of Wilmington in 1898 and subsequently expelled African Americans from North Carolina politics.

Supporters of white supremacy had their own interpretation of the Meck Dec. “The first ‘White Supremacy Club’ formed in recent years in North Carolina, was formed in Charlotte, N.C., in September, 1896,” Charlotte resident W.T. Moody proudly asserted in April of 1898, adding, “As Mecklenburg County first declared her independence against ‘British Tyranny,’ May 20th, 1775 . . . so Mecklenburg County first declared her independence against ‘negro rule.’”

In the first decades of the twentieth century, with Jim Crow segregation firmly established, Meck Dec celebrations focused on showcasing Charlotte’s economic growth.

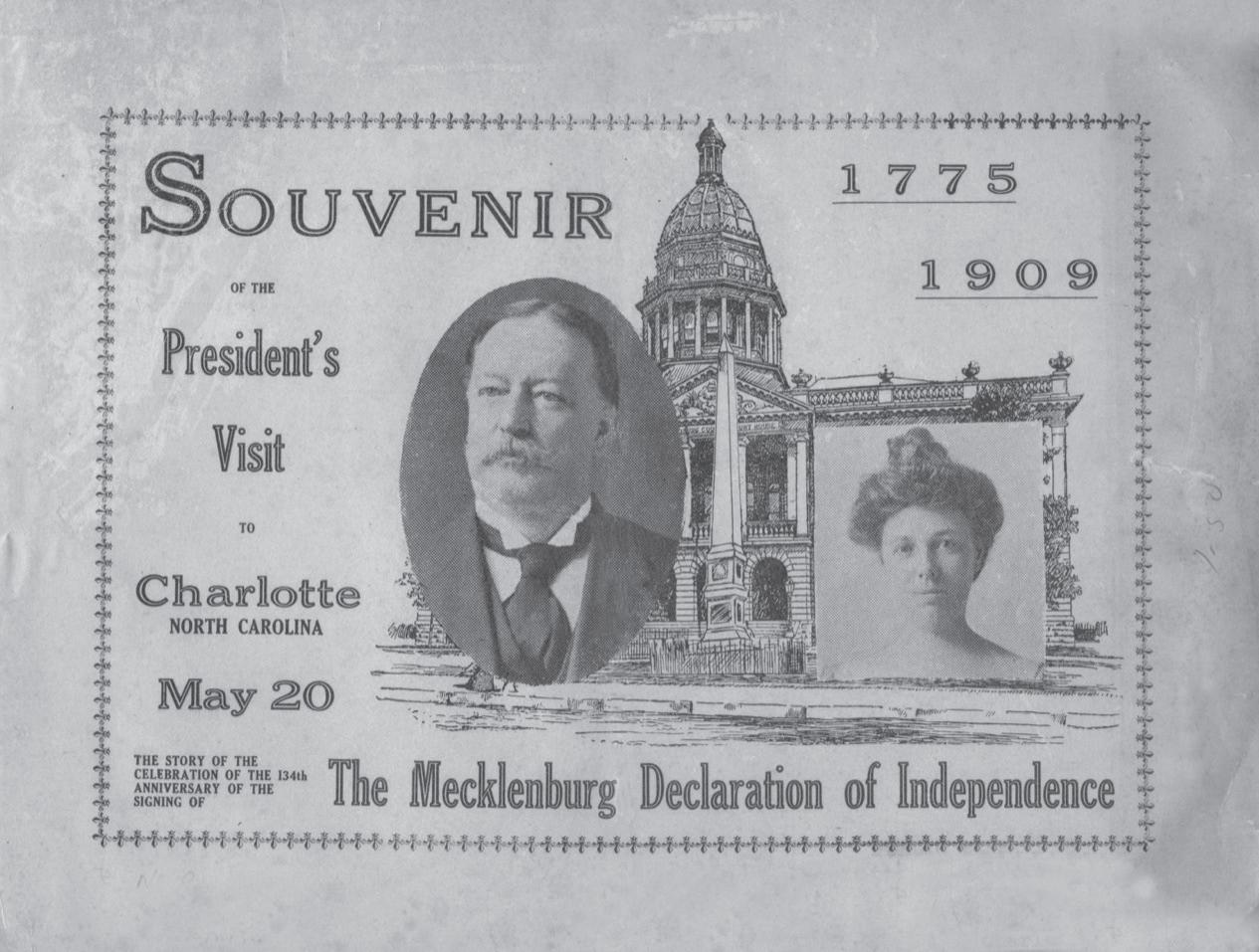

President William Howard Taft attended the 1909 festivities, where he and an estimated 20,000 spectators braved a driving rainstorm to view military regiments, marching bands and fraternal organizations, as well as floats that displayed items such as rubber tires, bathtubs, bedroom furniture, pianos, “fancy” chickens, harvesting equipment and a locomotive.

President Woodrow Wilson was treated to an even more lavish display in 1916, a three-milelong parade that included a fleet of 51 Model T automobiles produced at Charlotte’s Ford Motor Company factory just the day before.

If any Black residents were featured at the events, the newspapers did not mention them, although Taft made a trip to Johnson C. Smith, where he exhorted students and staff to “make themselves necessary to the prosperity of the South,” and opined that it was “in the realm of agriculture the negro finds his natural field.”

By mid-century, however, race had become harder to ignore. When President Dwight Eisenhower arrived in Charlotte for the 1954 celebration, the lead headline read not “President Speaks Here Today,” but rather “COURT BANS SEGREGATION” — referring to the Supreme Court’s just-announced Brown decision. Intensifying civil rights activity created new opportunities for African Americans to link their actions to the Meck Dec, as Reginald

Hawkins did in 1963. Interest in the Declaration waned in the latter part of the twentieth century. President Gerald Ford came to the 200th anniversary celebration in 1975, but the city of Charlotte ceased officially observing the holiday soon afterward, and the county stopped giving its employees the day off in 1982. “Meck Dec Becomes Just Another Day” the

Charlotte Observer noted that year. Only 35 people attended the 1984 event. Efforts to promote the Declaration have revived in recent years, as 2003 saw the formation of the May 20th Society, a group of Charlotteans who have promoted the Declaration and its signers through lectures, dinners, school lesson plans, and other activities. In 2010, a statue of Captain Jack titled the

“Spirit of Mecklenburg” was placed on the Little

Sugar Creek Greenway. The Charlotte City Council now regularly declares the days around May 20 as “Mecklenburg

Declaration of Independence Week.” In 2015, the state of North Carolina began to offer residents the option of a “First in Freedom” license plate bearing the dates of the Meck Dec and of the Halifax Resolves.

As in the past, however, these activities only rarely encourage consideration of the Meck Dec’s full history, and generally sidestep the contradictions between its soaring call for freedom and North Carolina’s long history of slavery, disfranchisement and Jim Crow segregation.

We can do better. Let’s start.

A SOUVENIR TICKET FROM WILLIAM HOWARD TAFT’S MECK DEC DAY VISI T TO CHARLOTTE IN 1909.

INFO@QCNERVE.COM

New donors can earn up to $1,000 with 8 successful donations in the first month at BioLife while making a difference for people with rare diseases.

*NEW DONORS ONLY

Must present this coupon prior to the initial donation to receive a total of $125 on your first donation, a total of $150 on your second donation, a total of $150 on your third donation, a total of $125 on your fourth donation, a total of $100 on your fifth donation, a total of $150 on your sixth donation, a total of $100 on your seventh donation, and a total of $100 on your eighth successful donation. Initial donation must be completed by 6.7.21 and subsequent donations within 60 days. Coupon redeemable only upon completing successful donations. May not be combined with any other offer. Only at participating locations.

Offer Code: 67041-3006

Copyright © 2021 Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. All rights reserved.