11 minute read

Gen. Slocum tragedy pointed toward a r worldsafe

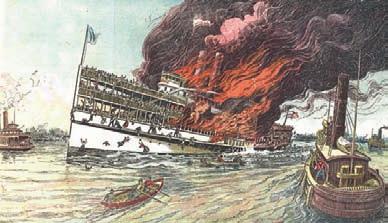

1904 TRIUMPH OVER TRAGEDY Ship fire claimed 1,300 lives in 1904

General Slocum survivors relocated to Middle Village

by Katherine Donlevy Associate Editor

Before the sinking of the Titanic on its way to the city or the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, the General Slocum disaster, though not as infamous, marked the greatest loss of life in New York City until Sept. 11, 2001.

To this day, the June 15, 1904 disaster that claimed as many as 1,342 lives, remains the city’s greatest maritime disaster.

The passenger steamboat had been chartered by St. Mark’s Evangelical Lutheran Church in the Little

Germany district of Manhattan to take about 1,400 passengers up the East River and across the Long Island Sound to Locust Grove in Eaton’s Neck, LI, for a picnic. The group, made up of almost only women and children, made the trip each year for nearly two decades.

Just 30 minutes after the ship began its Wednesday morning passage, a fire began in the Lamp Room. It only took an hour for the boat to burn and sink, stealing the victims’ lives rapidly.

“There was just a number of worstcase scenarios,” Kara Schlichting, an assistant professor of history at Queens College, said on the conditions that led to the tragedy. Had the ship been properly equipped for emergencies, the loss of life would have been much less significant.

First, the life preservers had rotted so severely that they had the consistency of wet cardboard, Schlichting said. The mothers who placed their children in the jackets and tossed them over the ship watched in horror as the kids were dragged straight below the surface.

The women themselves, dressed in the customary garb of layered wool despite the summer heat, were also dragged below the waves if they chose to jump overboard rather than take their chances with the flames.

“There was no maintenance of life boats, canvas [fire] hoses were rotten; they split at the seam as soon as the water moved through them,” Schlichting said, adding that the crew had little emergency training and had possibly never practiced fire drills. To make matters worse, the tragedy occurred in the choppy Hell Gate waters off Astoria made dangerous by multiple converging tides and currents.

“You couldn’t have had this happen in a worse place,” the professor said.

The burned General Slocum sank into the shallow water at North Brother Island near the Bronx shore. There were only 321 survivors.

“When you have a tragedy, sometimes good comes out of it,” said Bob Singleton, the executive director of the Greater Astoria Historical Society. “Every time we step on a boat or any public transportation, we are beneficiaries of this tragedy.”

The disaster helped spur the push toward stronger public safety laws, enforcement by federal and state government and the holding of company owners accountable for maintaining property to regulation standards. Captain William Van Schaick was charged with criminal negligence and failing to maintain proper fire drills and fire extinguishers and sentenced to 10 years, though he only served three before he was pardoned by President William Howard Taft. The ship’s owners, the Knickerbocker Steamship Co., was slapped with a fine, though relatively small considerThe General Slocum disaster of 1904 claimed approximately 1,300 lives, most of whom were women and children and all of whom were traveling to Long Island for a picnic. PHOTOS COURTESY GREATER ASTORIA HISTORICAL SOCIETY, ABOVE AND BELOW LEFT, BY KATHERINE DONLEVY; FILE PHOTO, RIGHT

ing there was evidence it had falsified inspection records.

This General Slocum tragedy, combined with the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire and sinking of the Titanic, which killed 146 and up to 1,635, respectively, several years later, contributed to the strict guidelines that we have today, Schlitching said.

Additionally, there were multiple accounts of heroism, including hospital workers on North Brother Island who jumped into the waters to try and save the drowning victims. Nearby boats pulled over to the burning ship without fear that their own craft would catch fire, but there was only so much the witnesses could do.

“Another tragedy is how helpless people on shore were. There was nothing those people could do,” Schlitching said.

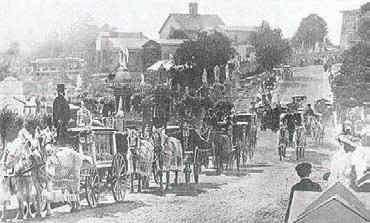

Singleton, who knew a few survivors of the disaster toward the end of their lifetimes, pointed to how the tragedy continued for years following the sinking of the General Slocum — almost every door in Little Germany displayed a black wreath signifying that they lost someone to the disaster. The residents couldn’t escape the trauma, so a great portion of the suffering families moved to Middle Village for a fresh start.

In the early 20th century, Queens was relatively rural and allowed the mourners to switch to a slower pace of life. The German families, out of the tenement buildings and in homes with backyards, rebuilt their community.

“They were able to forget. That was the promise of Queens — it was a place people could restart their lives,” Singleton said.

Survivors and the families of those who perished commemorated the loss with the Steamboat Fire Mass Memorial in All Faiths Cemetery in their new home in Middle Village. The monument was erected in 1905 and, though the last survivor of the disaster died in 2004, mourners and the General Slocum Memorial Association gather on the anniversary every year — except in 2020 because of the pandemic.

Other memorials have also been erected, including a fountain in Tompkins Square Park in the old Little Germany neighborhood, and a plaque in Astoria Park.

“History teaches us many lessons about who we are as a people, how we got here,” Singleton said on why General Slocum is commemorated year after year. “History is not just celebrating a ritual of the past, it is to tap into the body of the past and to receive wisdom of the past so we don’t have to do the same over and over again.” Q

Italian Charities of America is proud to offer a new program; Italian & Italian American Studies. Join us for these Interactive online learning classes.

The Hardships of Early Italian Immigrants and the Italian-American Experience Course Thursdays, November 19, 2020 to January 14th, 2021

This course will focus on the Italian-American experience from the late 19th century to early-mid 20th century. At the turn of the 19th century, Italians took part in mass migration and millions journeyed to the U.S. Italians faced discrimination and endured many hardships in America. Highlighting some rather dark moments in history, such as the 1891 lynching of Italians in New Orleans, the trial of Sacco and Vanzetti, the Red Scare, city living and working conditions, the Labor Movement, and WWII Internment Camps. We will also explore how Italian-Americans overcame many obstacles and contributed to American society.

Classes are on Zoom from 7:00pm to 9:00pm (EST). The fee for this course is $200, to regsiter go to our website: www.italiancharities.org and click the Italian & Italian American Studies tab to pay.

©2020 M1P • ITAL-078480

ITALIAN CHARITIES of AMERICA

A 501c3 not for profit organization Founded 1936 718-478-3100 italiancharitiesofamerica@gmail.com www.italiancharities.org

Our Vision To be recognized as the premier comprehensive business resource and driver of prosperity resulting in a vibrant Queens

Our Mission To foster connections, educate for success, develop/implement programs and advocate for members’ interests.

www.queenschamber.org www.queenschamber.org

Happy

Queens Queens Chronicle Chronicle

Queens Chamber of Commerce The Bulova Building 75-20 Astoria Blvd., Suite 140 Jackson Heights, NY 11370

Phone: 718-898-8500 Email: info@queenschamber.org

CONNECT WITH US

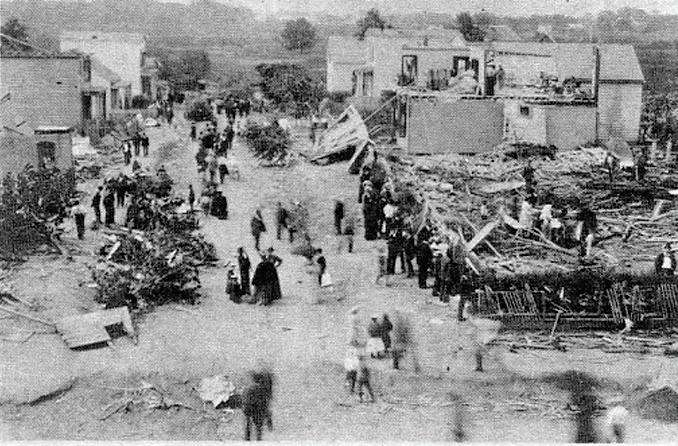

1895 TRIUMPH OVER TRAGEDY 125 years later: The Woodhaven cyclone

A fatal extreme weather event turned nabe into a spectacle

by Max Parrott Associate Editor

When the power grid went out this summer for thousands of Woodhaven residents during Tropical Storm Isaias, it wasn’t the first time that neighborhood became the focal point of an extreme weather event.

The area’s first known encounter with natural catastrophes dates back to 1895 when a fledgling community that consisted largely of farmland, with a hub of development built around the former Union Course racetrack, was hit by a deadly cyclone.

The storm not only knocked down houses, overturned a trolley car and killed at least one Woodhaven resident — possibly two according to some historical accounts — it brought droves of Manhattan residents out to the village as a form of both disaster relief and voyeurism, and put the community in the media spotlight.

The one uncontested fatality in Woodhaven that resulted from the storm befell a newly married and pregnant, 15-year-old girl named Louise Petroquien — spelled Petrogmen in some sources — who was struck by a beam after she walked outside her home to see what the commotion was about.

Asked how the neighborhood has adapted its response to emergency weather situations, neighborhood historian Ed Wendell said that this summer’s storm shows that the many of the same vulnerabilities exist in 2020.

“We’ve learned nothing,” said Wendell. “[Isaias] was no cyclone. That was no microburst, you know what I mean? And yet it did tremendous damage, with old uncared-for trees with weak roots getting ripped out.”

Though it wasn’t in Woodhaven, a wind-related fatality like Petroquien’s also resulted in the summer’s storm about 4 miles east of the neighborhood. A Bronx man died when the storm’s gusts blew a tree over on top of a car at 143rd Street and 84th Drive in Briarwood.

It was the afternoon of July 13, 1895, when what newspapers described as a tornado first ripped though Cherry Hill, NJ, and made its way through Harlem, before traveling south to Woodhaven. Wendell clarified that most people refer to the storm as a cyclone rather than a tornado, but some argue that neither accurately categorizes the storm by current meteorological standards.

Sometime after 4 p.m. the cyclone descended on the neighborhood, leaving a trail of destruction in its wake — the damages amounting to the equivalent of nearly half a million dollars in that period’s currency — over $15 million today.

“It tore down trees, tore up light poles. It tossed over a trolley car, was ripping over tombstones. So it was no doubt, a very, very powerful storm,” Wendell said.

In 1895 Woodhaven was in a transitional phase, where everything north of Jamaica Avenue was occupied almost exclusively by farms and the land south was in the process of development, said Wendell. Jamaica Avenue had just gotten an electric trolley to serve the bustling village center of Woodhaven, which contained a factory, a bank and a number of businesses built up during the early 19th century around the track, located between what is now Jamaica Avenue to the north and Atlantic Avenue to the south along 78th Street, which was sold to make housing in 1972.

A lot of the damage was centralized in the area along Rockaway Boulevard in an area that now technically is in the northern part of Ozone Park. For instance, a brick schoolhouse at Rockaway and 84th Street, which lay

People gather at Rockaway Boulevard at 83rd Street, above. Rubble surrounds the ruins of the schoolhouse at Rockaway Boulevard and 84th Street, bottom left and center. The remains of houses and debris scattered by the cyclone fill the village, bottom right. PHOTOS COURTESY PROJECT WOODHAVEN

directly in the cyclone’s path, was completely demolished. Luckily it was out of session for the summer.

One significant difference between Isaias and the cyclone of 1895 is the amount of attention Woodhaven got as a result of the 19th century catastrophe. The New York Sun described the events of the storm like this:

“The tornado on Saturday that killed one, wounded forty, demolished fifteen houses and partially wrecked thirty more, was followed by the largest crowd of sightseers that ever collected in town limits.”

Crowds of people from New York and Brooklyn traveled on the new elevated trolley to see the destruction firsthand, and to donate to the affect-

ed families — some of whom suddenly found their houses in ruins, in an era long before FEMA.

The Sun reported that around 100,000 people visited the village over the next day — an event that School Commissioner John B. Merrill took advantage of by collecting donations for the newly homeless residents of the village.

Merrill reportedly picked a keg out of the ruins and set up a soapbox asking the sightseers to fill it with money for the needy. Fellow commissioners rushed to help the effort shouting “Give ’em what you can spare. Put it in the barrel. Every little counts but don’t fill it with pennies.”

At the same time, Woodhaven’s surviving saloons, which were numerous around the racetrack, opened up even though it was illegal to do so on a Sunday, and began serving beer on tap to the crowds that appeared. Other villagers followed Merrill’s lead and began collecting money from the visitors in empty kegs around the community, the Sun reported. The relatives of Petroquien began selling roses to honor her memory, Wendell added.

At the end of the day, when the money that Merrill collected was pooled and counted, it was found to be $738.50, which the Sun reported went directly to the sick and injured residents. Q