5 minute read

WORSENING OPIOID CRISIS Two Queens emergency room doctors,

“When I was around 17, I started drinking,” he told the Chronicle. “It was excessive from the beginning. The drinking culture at the time was kind of all about getting as intoxicated as possible.”

That drinking turned into an affinity for weed, then pain killers and heroin.

“[Heroin] was easily accessible and a lot cheaper,” Mike said of the drug. “And I was in my early 20s at the time, so there’s not a lot of consequential thinking going on. I was just using to get the next high.”

He never tried fentanyl because at the time, it hadn’t yet become widespread.

“I remember hearing about it towards the end of my addiction, but never myself took it or was involved with it,” he explained. “I think if it was as easily available as it is now, maybe I wouldn’t be around anymore, which is a very scary thing to think about.”

Situations like Mike’s are not uncommon — addictions can progress from drinking to drugs in a fairly short matter of time.

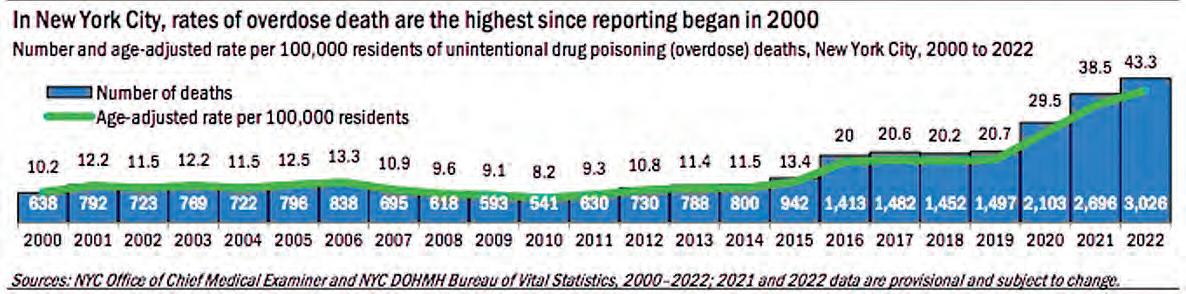

Drug-related deaths hit a record high in 2022. According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 109,680 Americans died of an overdose last year.

In New York, according to data from the city Health Department, 3,026 people died of an overdose in 2022 — a 12 percent increase from 2021. The city said 85 percent of overdoses involved an opioid, with fentanyl present in 81 percent. In Queens, 469 succumbed to drugs last year.

At a recent certification event in Glendale for Narcan, a time-sensitive overdose antidote, Dr. David Collymore, the chief medical officer of Acacia Network, said, “I was speaking to a gentleman earlier today who began using marijuana at the age of 11, and quickly progressed into opioid use.”

He continued, “Queens has the distinction of having the second-fastest increasing rate [of overdose deaths] in the boroughs of New York. ... It’s a problem that has affected every single demographic, every single borough.”

At the event, Collymore gave out about 30 overdose reversal kits to participants.

The crisis is deeply felt in hospital emergency rooms.

“We probably get somewhere on the order of about 250 cases of what we identify as being different types of overdoses,” said Dr. Christopher Calandrella, chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine at Long Island Jewish Hospital Forest Hills. “That includes things that are acquired on the street and prescription drugs as well.”

Dr. Shi-Wen Lee, chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine at Jamaica Hospital Medical Center, when asked about the state of the opioid crisis, said the numbers for this year aren’t promising so far.

“It’s as bad as the previous year. It may be worse, and we’re still not up to the end of the year. We’re still accumulating data, but it looks like it’s going to meet and exceed what we have seen last year.”

Christina Clemente, the associate director at Long Island Consultation Center in Elmhurst, a counseling and treatment facility, when asked if she’s seeing more patients come in with drug addiction issues, said, “Since the pandemic? Oh, absolutely.”

Asked if fentanyl is often seen in overdoses in Queens, the doctors both said it’s a mix.

“A lot of stuff is laced with fentanyl these days, so no one knows what they’re getting,” Lee said. “There’s a widespread use of fentanyl ingredients in a lot of [street] drugs. ... So a patient might think they’re smoking crack, but it really has fentanyl laced in it.”

“Substances get mixed with other substances, which makes it really difficult to tell the difference,” Calandrella said. “More and more things are being mixed with other medications, and so that can be a real challenge sometimes, identifying the real culprit.”

Access to prescription opioids can contribute to the beginning of an addiction as well.

“There’s been a very conscious effort to avoid prescription of medications that contain opioids,” Calandrella said. “... I’d like to think that there is more of an effort going into reducing prescription medication use.”

As a former addict, Mike is keenly aware of the issues that may arise when receiving prescriptions for opiates.

“I worry a lot about the elderly population. As you get older, you start getting more aches and pains and things going wrong, and opiates become something that’s offered,” he said. “It’s something that I think everybody — not just addicts — need to be careful with, because it kind of completely takes control. You become physically dependent, and I think anyone can get addicted.”

“Traditionally you would think that you have to have some sort of addictive personality,” Lee said. “But we also find that normal people get hooked onto these drugs. They’re just mom and dad, or brother or sister, like you and I.”

Though the opioid crisis is worsening, there are things being done to address it.

LIJ FH has a Pain and Addiction Care Accredited Emergency Department, and the hospital makes an active effort to help those in the community.

“We have been doing a lot around education. We had our third observed International Opioid Awareness Day, which was on the 31st of August.” Calandrella explained. “And Northwell had like 34 sites that participated in this event, and gave out over 2,300 kits. ... These are really important harm prevention programs. Just at our site, we gave out over 250 kits.”

Calandrella also discussed the importance of education, saying people should have an understanding of what medications they’re taking and the ingredients inside — especially in pain medicines. “Those are the medications that need to be locked up safely or discarded.”

He said that when disposing of the medications, they should not be flushed down the toi- let. People should look online for a disposal location. “There are a number of places where the FDA has disposal programs.”

JHMC also makes an effort to assist those suffering from addiction.

“We have an induction program here in the ED,” Lee said. “Patients might be coming in for an ankle fracture and we ask a question. If they fit the criteria and they have opiate use disorder, if they consent, we could start the induction program.

“They’ll go home and we’ll arrange for them to have a follow-up as an outpatient to continue the program. It’s a time-consuming resource, obviously. The doctors are busy taking care of strokes and heart attacks and trauma, but we do have to be conscious and take our time and evaluate patients for opioid use disorder because it’s destroying our community.”

JHMC also has a relay program — if someone is admitted with a potentially life-threatening overdose, a nurse will contact an ex-user to come in and be a peer advocate. They provide education and a Narcan kit, send the patient home and check in for up to 90 days.

“We meet monthly to go over special patients of concern,” Lee said. “And from time to time, we get names so we can look out for those who need additional care.”

Asked if any legislative changes could help the crisis, Calandrella said current resources should be expanded.

“Nyc.gov has educational resources for administration of Narcan, so that’s one component. Making the kits more available is another component,” he said. “But this has to be a multilevel approach. There has to be more done to reduce access for these medications and drugs on the street.”

Both emergency department chairs recalled experiences with overdose patients that stuck with them.