t

contact me to view my MPhil Dissertation]

Design Projects

Table of Contents

Writing Samples

Curriculum Vitae

To Win an Election

NUS | M(Arch) Thesis | August 2020 - May 2021

Monument to the Freedom of Speech

NUS | Year 4 Semester 2 | January - May 2020

#ALTLife

NUS | Year 4 Semester 1 | August - November 2019 (Featured in To-Gather, Singapore's Pavilion in Singapore Vennice Biennale 2021)

Building 28

NUS | Year 3 Semester 2 | January - May 2018

Atelier théâtre

NUS | Year 3 Semester 1 (Exchange in Tongji University) | August - November 2018

Equfinality

NUS | Year 2 Semester 2 | January - May 2018

(No) Monkey Business

NUS | Year 2 Semester 1 | August - November 2017

Confronting the Postfeminist Media Urban-scape

University of Cambridge | M(Phil) in Architecture and Urban Studies, Lent Term | January 2021 - April 2022

Through the Lens of Materiality

University of Cambridge | M(Phil) in Architecture and Urban Studies, Michaelmas Term | October 2021 - November 2021

Reconceptualizing Female Spectatorship

NUS | M(Arch) Semester 1 | August 2020 - May 2021

“But where’s the art?”

NUS | M(Arch) Year 4 Semester 2 | January - May 2020

Education

MPhil Architecture and Urban Studies (Distinction), October 2021 – June 2022

University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Dissertation: A study on the dialectics of spontaneity and organization in social movements, using the case studies of the January 25 Revolution in Cairo, the 15-M/Indignados Movement in Madrid, and the Occupy Wall Street movement in New York City. The study is positioned at the intersection of urban theory, media and communications theory, and new social movement theory, and was conducted with the aid of original mappings constructed using AutoCad and Adobe Illustrator.

Coursework includes: Graduate Research Methods, Introduction to Socio-politics and Culture of Architecture and the City, Architecture outside the Norm, Landscape: Image, Territory, Park and Hinterland, Managing Urban Change

Master of Architecture, August 2020 – May 2021

National University of Singapore (NUS), Singapore

Thesis: A study on the tactical appropriations of Singapore’s “Heartland” infrastructure undertaken by Opposition parties, situated at the intersection of urban theory, media and communications theory, and political theory. The study was faciliated by interviews and original mappings constructed using AutoCad, Rhinoceros, and Grasshopper.

Design Proposal: Explored the notion of aesthetics in disseminated political imagery, such as those generated during the 2014 Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong. Aesthetic parameters were extracted, after which political imagery was designed for Opposition parties, facilitated by use of original architectural modules situated in “Heartland” infrastructure. This imagery was to be disseminated via social media as part of Opposition party campaigns, facilitating the construction of alternative identities within Singapore’s political landscape.

Bachelor of Arts in Architecture with Honours (Distinction), August 2016 – May 2020

National University of Singapore, Singapore

Coursework includes: Design 1-6, Options Design Research Studio 1-2, Reading Visual Images, History and Theory of Southeast Asia, Environment and Civil Society in Singapore, History and Theory of Western Architecture, Introduction to Philosophy, Politics, and Economics, Urban Design Theory and Praxis

Student Exchange Program, August 2018 – January 2019

College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University, Shanghai, China

Coursework includes: Future of Retail Space, Frontiers of Architecture: Craft, Urban Design: Emergence, Evolution and New Topics, Urban Mobility and Transport: Emerging Issues and Planning Practices in China, Chinese and Western Classical Garden, Relationship between the Culture and the Moulding Arts in China, Quantifying the Immeasurable: Parameterizing Urban and Architectural Aesthetics using BIM and Virtual Design/Construction Methodology

Teaching Experience

Temporary Workshop Facilitator for Introductory Software Workshop (Unity), April 2020

National University of Singapore, Singapore

Department of Architecture

Key Tasks: Introductory step-by-step guide on how to use Unity

simjingxi123@gmail.com

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/rachel-sim-50b493142/

Architectural Portfolio: https://simjingxi123.wixsite.com/racheljsim

Architectural Portfolio (Issuu): https://issuu.com/racheljs/docs/rach_design_portfolio_writing_samples

Teaching Assistant, January 2020 – April 2020

Module: History and Theory of Western Architecture

National University of Singapore, Singapore Department of Architecture

Key Tasks: Conduct weekly seminars, grade reading responses, and provide essay consultations

Teaching Assistant, August 2019 – November 2019

Module: History of Southeast Asian Architecture

National University of Singapore, Singapore Department of Architecture

Key Tasks: Conduct weekly consultations for essay writing, grade essay assignments and student presentations

Research Experience

[Current Role] Research Assistant under Dr. Lilian Chee, September 2022 –NUS, Singapore

Department of Architecture

Research Project involved in: “Foundations of Home-based Work: A Singapore Study”, supported by Social Science Research Thematic Grants, Singapore

Key Tasks: Assisting with administrative duties, including budgetary work, procurement, website design and conference planning. Co-leading a seminar module entitled “Domestic Capital and Workaround”, which entails the revision of module readings, giving student briefings, and commenting on student presentations, reading responses, and essays. Involved also in a visual ethnography of home-based work, to be conducted in neighbourhoods around Singapore. Is expected to be involved in the editing of a special journal series, as well as a journal paper on home-based work and the architectural typologies that accommodate it.

Brief Description of Research Project: Foundations of Home-based Work is an inter-disciplinary project seeking to understand how home-based work is built into homes and neighbourhoods, and what it builds for them. Supported by the Social Science Research Thematic Grant (WBS no.: A-0008463-01-00; IRB no.: NUS-IRB-2021-799), the team comprises of established researchers across the National University of Singapore’s Department of Architecture, Department of Communications and New Media, and Yale-NUS. The project was launched in September of 2021, with the aim of offering foundational scholarship to meet a gap in scholarly insight into the past and present experience of home-based work in Singapore. See: https://www.makingdo.org/about

Research Assistant under Dr. Heng Chye Kiang, May 2020 – August 2021

NUS, Singapore

Department of Architecture

Book Publication involved in: Vertical Cities Asia (upcoming)

Key Tasks: Assisted in the compilation of content – including essays and competition submissions – generated across a 5-year program organized by NUS, titled the Vertical Cities Asia International Design Competition and Symposium. Involved in the initial reframing of content spanning all 5 symposiums to emphasize the importance of verticality and densification for evolving

Asian cities. Heavily involved in translation (Chinese to English) and editing in the later stages of the project.

Brief Description of Research Project: The Vertical Cities Asia International Design Competition and Symposium was created to encourage design explorations and research into the prospects of new models for the increasingly vertical, dense, and intense urban environments in Asia.

See: https://nuspress.nus.edu.sg/products/vertical-cities-asia

Research Assistant under Dr. Simone Chung, May 2019 – July 2019

National University of Singapore, Singapore Department of Architecture

Journal Publication involved in: Deciphering the Spatial Rhetorics of Millennial Nomads (upcoming)

Key Tasks: Conducted semi-structured virtual interviews with millennial nomads (sourced from Facebook and other social media platforms); processed their responses through the generation of ArcGIS mobility mappings and qualitative coding in NVivo.

Brief Description of Research Project: Understanding the formation and management of a multi-mobile millennial nomad’s identity and spatial practices in the private domain, urban environment and the digital realm. Core research methodologies include virtual ethnography, spatial mapping, and systematic qualitative analysis.

See: https://millennialnomadspace.com/about/

Research Assistant under Dr. Lilian Chee, May 2019 – July 2019 National University of Singapore, Singapore Department of Architecture

Book Publication involved in: Art in Public Space: Singapore (2022)

Key Tasks: Sourced and condensed research material into essays covering a range of topics, e.g. implications of IndonesiaMalaysia-Singapore growth triangle on human mobility, impact of colonialism on Singapore’s tropical landscape, and the evolution of public art in Singapore. Indexed and compiled an Appendix for an upcoming book on public art in the Singaporean city core – Art in Public Space: Singapore (2022), commissioned by the Urban Development Authority in 2018.

Brief Description of Research Project: Tracing the history of public art in Singapore and postulating the future trajectory of public art in Singapore.

Conference Planning Experience

Organizer of Speakers’ Series, November 2021 – expected October 2022 Newnham College, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Key Tasks: Organized the one-day Newnham Rebels Graduate Conference (June 2022) around the theme “Feminism in the Everyday”. Responsibilities included liaising with invited speakers, emceeing duties, logistics, and social media publicity. About the theme: The theme was designed to bridge the gap between feminist theory and feminism in real life, that is, how feminism can be expressed in the domestic or work situations, etc. Invited speakers included: Anne Thorne, EDIT Collective, Araminta Hall, Jasvinder Sanghera CBE, and Empower Her Voice.

Planning Committee Member of NUS M(Arch) Gradshow, May-June 2021 NUS, Singapore

Key Tasks: Planned an hour-long introductory seminar on architectural pedagogy and the relevance of thesis projects to architectural students; presented Masters’ thesis project in a sociopolitical/geopolitical seminar on fieldwork/ethnographic practices in socio-politically oriented architectural projects.

Practical Experience

Studio Marque

Architectural Intern, June 2018 – August 2018

Key Tasks: Generation of digital graphics using AutoCAD and SketchUp; assisted with interior designs of residential projects

and resorts in Indonesia.

FYE Design Studio

Architectural Intern, July 2017 – July 2017

Key Tasks: Generation of digital graphics using AutoCAD and SketchUp; assisted with the interior designs of residential projects, ranging from condominium units to townhouses.

Surbana Jurong Pte Ltd

Architectural Intern under the departments of Urban Development and Townships (Public Housing), March 2016 – July 2016

Key Tasks: Generation of digital graphics using AutoCAD and SketchUp; assisted with the interior revamp of Surbana Jurong office a senior centre.

Awards

Dean’s List, 2020

Student Achievements Awards (Gold), 2018

Participatory Design Project | NUS SMILE Village Overseas Community-involvement project

Exhibitions

ArchiVAL 2020 and 2021

Showcased design work in annual exhibition by the NUS Department of Architecture

CityEx 2017 and 2018

Showcased design work in annual exhibition by the NUS Department of Architecture, in partnership with Urban Redevelopment Authority.

Technical Skills

Adobe Photoshop, Illustrator, InDesign Rhinoceros, Grasshopper AutoCAD

SketchUp

Microsoft Word, Excel, PowerPoint Fluent in Mandarin and English

Volunteer Work and Other Roles

SMILE Village Overseas Educational Program, May 2017

National University of Singapore

Key Tasks: Holding participatory design workshops for the construction of a public shelter, part of a greater initiative to reinvigorate public spaces

Co-organizer of Speakers’ Series, November 2021 – October 2022

Newnham College, University of Cambridge

Key Tasks: Organizing student and graduate conferences

NUS M(Arch) Gradshow, May-June 2021

National University of Singapore

Key Tasks: Planned introductory seminar, presented in sociopolitical/geopolitical seminar

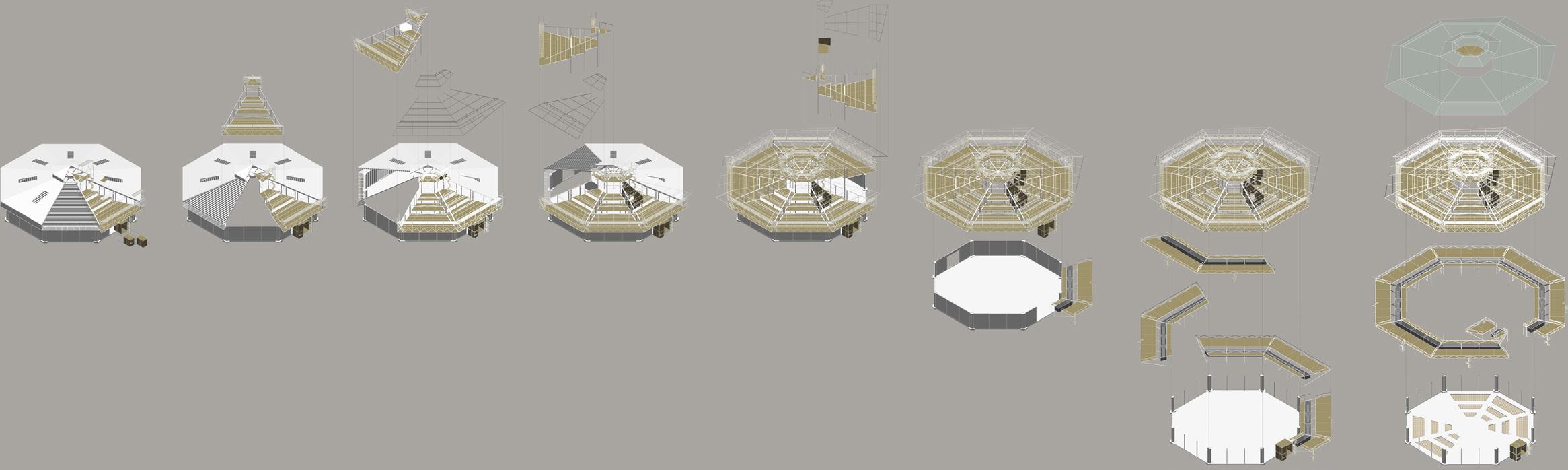

THIS project functions as an inquiry into the possible spatial negotiation of the communitarian ideology of Singapore’s ruling party, PAP (People's Action Party), through the study of Opposition parties’ spatial practices. It first examines how an ideological consensus with the citizenry is produced and reproduced by the state’s built community infrastructure in the “Heartlands” (suburban residential areas in Singapore with subsidized public housing), thus projecting their political identity into these areas. Such a process, combined with the universality of Heartland community infrastructure, allows the ruling party to exert a virtual monopoly over grassroots activities and many other aspects of everyday life, engendering further ideological consensus amongst the governed (Chua 1995: 128). Most of these infrastructures, such as CCs (Community Centres), are also banned from Opposition use.

Amidst this entrenched hegemony, how then could we possibly conceive of an alternative “Heartland”? Michel de Certeau (1988: 96) offers us a lens, in the form of “strategy” and “tactics”; upon PAP’s fixed infrastructure, Opposition political parties “walk”, using transient tactics to project alternative political identities into the infrastructure. WP (Workers’ Party), in particular, employs everyday practices emblematic of its stance – a defender of blue collared workers and the lesser privileged. While the PAP imposes buildings of permanence upon Heartlanders, WP appropriates HDB flats via transient void deck consultations, setting up time-based systems through which they conduct their weekly welfare events and distributions. In a bid to express their own brand of community outreach, they fluidly traverse multiple flats within their constituencies to reach out to their constituents. It is through such tactics, that WP manipulates space and redefines some of the community rituals imposed upon the citizenry by the incumbent majority. Given a political terrain with marginal spatial allowance for Opposition political outreach, how much more can alternative political voices negotiate dominant ideologies through space? And more importantly, how can the everyday citizen resist and potentially play a role in enriching Singapore’s – or any similar – political landscape?

Months of research have culminated in the decision to capitalize on the power of social media, specifically the sharing and reposting of ‘aesthetic’ digital images to further the impact of the Opposition’s political outreach. Inspired by Hong Kong’s umbrellas and Thailand’s rubber duckies, these digital images would be staged using modified everyday objects, easy enough for the everyday citizen to stack or agglomerate into larger forms. Using WP as a case study, this project explores spatial and architectonic ways of constructing alternative forms of political identity within the Heartlands – as well as the meaningful augmentation of WP’s tactics – through social media.

With that, I hope to have provided somewhat of an answer to my own questions.

*Please refer to my report for more graphics and a more detailed explication of this project. It can be found here: https://simjingxi123.wixsite.com/racheljsim/copy-of-reconceptualizing-female-spec.

Semester: Master of Architecture, Thesis (National Univeristy of Singapore) | Project type: Individual Software(s) used: Procreate, Photoshop, InDesign, AutoCAD, Rhinoceros

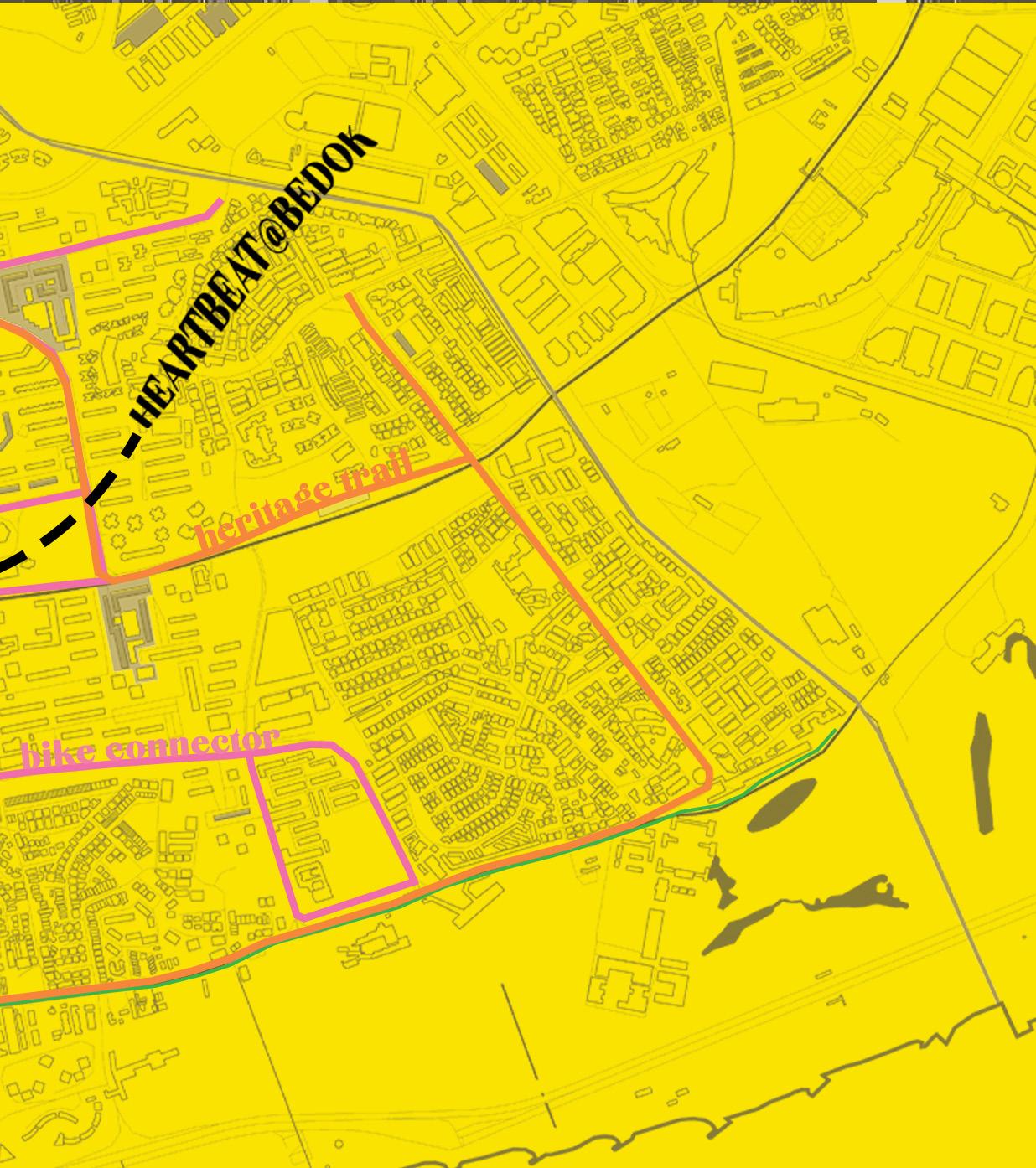

Ubiquity of PAP infrastructure, taking East Coast Group Representation Constituency (GRC) as an example

Ubiquity of PAP infrastructure, taking East Coast Group Representation Constituency (GRC) as an example

INVESTIGATIVE MAPPING - PAP STRATEGIES

Singapore’s Heartlands are made up of many New Towns. Within each New Town, a Town Centre serves public housing estates radiating out from it, while estates further away from it are served by Neighbourhood Centres (NCs), smaller-scale sub-centres that included coffeeshops, hawker centres, markets and various other Small & Medium Enterprises selling basic necessities. PAP’s near-universal provision of easily accessible goods and services, part and parcel of people’s everyday routines, signify an irrevocably deep – and as a result, virtually unnoticeable – political penetration into everyday life.

A representation of the New Town’s checkerboard urban layout

A representation of the New Town’s checkerboard urban layout

Various trails/connectors converging at - and used to draw people into - the Town Centre, taking the Bedok division of East Coast GRC as an example

INVESTIGATIVE MAPPING -

TACTICS

Movement of furniture during the Meet-the-People’s session (MPS), conducted in the Kaki Bukit division of Aljunied GRC

Movement of furniture during the Meet-the-People’s session (MPS), conducted in the Kaki Bukit division of Aljunied GRC

INVESTIGATIVE MAPPING - WP TACTICS

MPS - more transient inhabitation of places in comparison to PAP’s strategies

WP’s welfare distribution route, conducted in the Kaki Bukit division of Aljunied GRC

WP’s welfare distribution route, conducted in the Kaki Bukit division of Aljunied GRC

INVESTIGATIVE MAPPING - WP TACTICS

The transient inhabitation of places remains true for volunteer/welfare programmes

WP’s welfare distribution route, conducted in the Kaki Bukit division of Aljunied GRC

WP’s welfare distribution route, conducted in the Kaki Bukit division of Aljunied GRC

INVESTIGATIVE MAPPING - WP TACTICS

DESIGN SCHEME - CREATION OF ‘AESTHETIC’ DIGITAL IMAGES

Modifying everyday objects for the everyday citizen to stack or agglomerate into larger forms

DESIGN SCHEME - CREATION OF ‘AESTHETIC’ DIGITAL IMAGES

Modifying everyday objects for the everyday citizen to stack or agglomerate into larger forms

DESIGN

OF

DESIGN SCHEME

OF WELFARE PROGRAMMES

DESIGN SCHEME

MANUALS

BE DISTRIBUTED TO

PUBLIC

ARTICLE14 (1) guarantees all Singaporean citizens the rights to “freedom of speech and expression” , peaceful assembly “without arms” , and “the right to form associations” . Yet this is subject to Article 14 (2), whereby the parliament may by law impose on the rights conferred by 14 (1) as it considered “ necessary or expedient in the interest of the security of Singapore” , “friendly relations with other countries, public order or morality” (Constitution of the Republic of Singapore 2021), terms that are purposefully vague. The terms “necessary or expedient” , in particular, confers upon the Parliament the power to a “multifarious and multifaceted approach,” with no questioning of whether the legislation is “reasonable” and effectively according them a position of unlimited power over the people. The Courts and their ability to persecute, thus, are the instruments through which this power is exercised.

These laws do not cease to exist within the boundaries of Hong Lim Park, Singapore's only spot for legal (peaceful) political protest and public assembly since 2001; a reality which effectively makes the Park a veritable landmine for persecution. In a spatial manifestation of surveillance, the Park is circumscribed - almost imposed uponby the State Courts, the Kreta Ayer Police Neighbourhood Centre, and the Attorney General’s Chambers, given the noticeable height difference between these symbols of authority and the flat green Park. This reinforces the idea that political protest has effectively been ‘quarantined’ within the Park

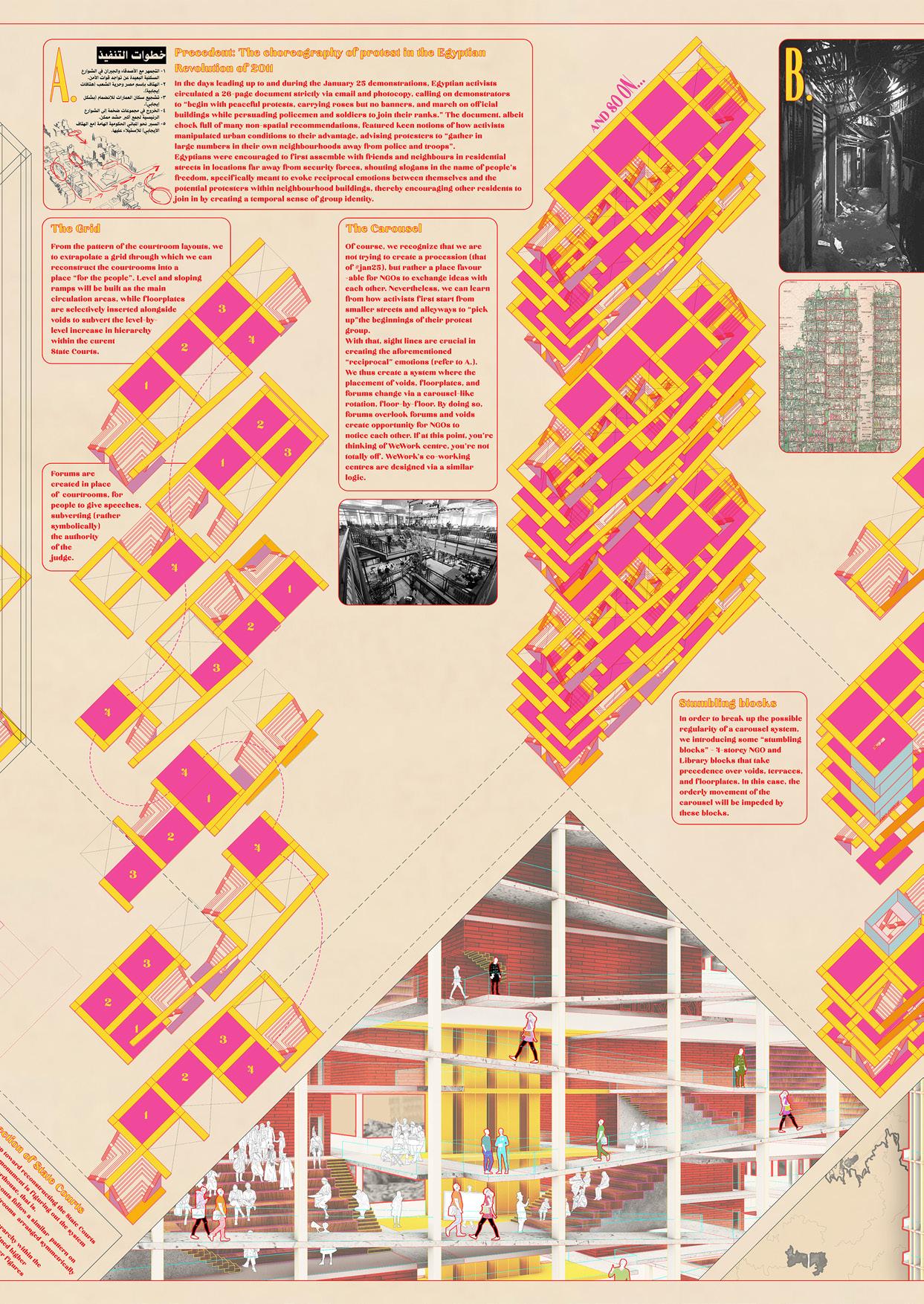

Monument to the Freedom of Speech was conceived on the grounds of Hong Lim Park as a satirical statement on the lack of legal immunity within a space designated for protest; to contest the very ‘public’ character of the space (Butler 2018: 71); and most of all, to give protesters an agora where they could freely air their views and exchange their ideas.

The architectural design of the New State Courts was chosen through an open-call competition (Frearson 2021). To the competition jury, it was “symbolically open and accessible to the public”, and sufficiently explored the “relationship between the city and its civic buildings”. I tried reconciling this statement with the legal mechanisms set in place to deter politically-sensitive protest, as well as the design of the Courts, where its symbolically open facade disguised the hierarchy that was very much still present - courtrooms arranged in order of increasing gravity of offense as the floor level increased; judges seated in the most spatially dominant position of the courtrooms. Thus, if we defined ‘public’ as the protesters, how much of the Courts were actually designed ‘for the public’?

In response to my own question, I made the decision to ‘mirror’ the State Courts, conceptually deconstructing and reconstructing its material form unto the grounds of Hong Lim Park, making a satirical piece of architecture in which protesters could truly and freely protest. This building would also exploit Hong Lim’s legal boundaries as a space for protest, and thereby provide protesters with a platform on which they could contest the very ‘public’ character of the space. Without further ado, dear reader, please join me in this process of satirical deconstruction, and the subsequent reconstruction of the Monument to the Freedom of Speech

Semester: Y4S2 (National Univeristy of Singapore) | Project type: Individual Software(s) used: Photoshop, InDesign, AutoCAD, Rhinoceros, Grasshopper

‘MIRRORING’ OF THE NEW STATE COURTS ONTO THE GROUNDS OF HONG LIM PARK

This conceptually borrows from Comaroff and Ong’s “Horror in Architecture” (2013), in which they discuss reflexive doubling, a process of creating “imperfect” architectural replicas which could function as insights to evolving societal contexts. Inversely, the perfect clone could also function as a “potentially destabilizing kind of deviance” (Comaroff and Ong 2013: 70). By latching onto these two devices, I could symbolically appropriate the form of the newly-built State Courts, the very apparatus meting out punishment to the protesters, and architecturally parody the values it supposedly represented.

PROCESS INFOGRAPHIC - THE RECONSTRUCTION AND DECONSTRUCTION OF THE NEW STATE COURTS

Firstly, the existing State Courts building was abstracted – based on its floorplans – into a three-dimensional grid, through which new “protester” functions would be ordered. This order, if you could imagine, would work like a carousel system, with each successive functional block situated at steadily increasing heights. These blocks would then be clad with the same terracotta that adorn the State courtrooms, encased within the same white columns that distinguish the façade of the State Courts. Via this imperfect cloning, the Courts undergo transformation to take on a more democratic, yet uncannily similar form.

“...and most of all, to give protesters an agora where they could freely air their views and exchange their ideas.”

“...we do want to create a labyrith to confuse authorities, as well as craft "alleyways" mostly hidden from the sight of people on the ground for people to discuss politically contentious issues ”

CENTURY technological advancements have metaphorically shrunken the world and allowed for global transpatiality. The introduction of virtual reality (VR) has intensified this phenomenon, augmenting two-dimensional social media platforms and providing an alternative to physical gathering spaces. Through the process of research, experimentation and observations, #ALTLIFE seeks to answer two major questions: the extent to which virtual and non-virtual realms feed into each other; and how the design of virtual spaces can be optimized to facilitate gatherings undertaken by existing communities. In order to ensure the success of our experimentation, we chose make a huge existing community our target group - the fan base of K-pop boyband BTS, commonly known as BTS ARMY. VRChat (VRC), a free-to-play massively multiplayer online virtual reality social platform built on user-generated ‘worlds’, was used as our medium. Phase 1 (Virtual Logs) was a pictorial documentation of VRC users over the course of 1 month, informing Phase 2 (Permutations), our creation of BTUniverse, a ‘world’ where calculated modifications were made over the course of 2 months to better understand the relationship between virtual design elements and user behavior. Phase 3 (VR Guidebook) was the final creation of a design ‘guidebook’ to aid designers in the creation of virtual alternative spaces.

BTUNIVERSE

Based on logs of our adventures in VRChat, we launched 4 permutations of our self-created world, BTUniverse, onto the multi-player

12:42 AM 25/09/19 Rest and Sleep

The gang decides to leave BTUniverse and chill out at Rest and Sleep. We dip our legs in the onsen-esque pool and sit down on the edge of it. We start talking about our favourite singers. Freal admits he's a massive fan of JJ Lin. Promocat introduces us to Keshi. Yoyo later brings a pillow to Periokiex for her virtual comfort.

1:06 AM 25/09/19 Rest and Sleep

A new user, LostCat, enters and everyone stops the ongoing conversation to welcome him into the mix. Not unlike social protocol in real life - to me, this virtual gang seems way more welcoming than most groups in real life though.

1:20 AM 25/09/19 Rest and Sleep

LostCat is familiar with PromoCat. PromoCat starts detailing how they met virtually - and how they (PokiCat, LostCat, himself) changed their usernames to end with 'cat'. Seems like a way of establishing friendship bonds in the virtual world, not unlike cloning each other's avatars (as in Secret Base Anohana). (reciprocal movements)

1:22 AM 25/09/19 Rest and Sleep

PokiCat starts crawling along the edge - people will play with anything in the virtual world. Freal joins her.

5:05 PM Batch 2 25/09/19

BTUniverse Permutation 1

5:14 PM Batch 2 25/09/19

BTUniverse Permutation 1

5:16 PM

Batch 2 25/09/19

BTUniverse Permutation 1

5:17 PM Batch 2 25/09/19

BTUniverse Permutation 1

I AFK at BTUniverse while doing something else when Promocat and his korean friend, Gyumina, comes to find me. We hang aroud the central, getting to know each other. Promocat starts grabbing the plushies and arranging them in mid-air.

Soon after, Younea turns up and we hang out around the same area for while longer. Younea and Gyumina bond quickly as they are both Korean. Younea grabs a pen from table3 and starts drawing on the adjacent column. The columns flanking table 3 seem to define the 'drawing area', as seen in the previous group who visited as well.

Another korean, Tiffi, appears and the three went off to a corner to mingle in korean. Gyumina decides to AFK on the floor while Promocat pickes up a pen to draw. Meanwhile, Younea and Tiffi go around from one BTS portrait to another, discussing who's-who. (picture 2 and 3)

Meanwhile, Promocat starts placing plushies in front of Gyumina's AFK avatar and drawing on his face, similar to shine-building behaviour we noticed before around AFK avatars. Younea then brings a pen all the way to the steps and starts drawing on the wall. This is the first time I notice a user drawing somewhere other than table 3 and it's periphery.

PHASE 1. VIRTUAL LOGS OF VRCHAT USER ACTIVITY

- Written and pictorial documentation of observations in VRChat, focusing specifically on the relationship between material elements (e.g. virutal furniture, walls, mirrors) in three-dimensional virtual multiplayer spaces and user behaviour

- Two accounts (@Racheljs123, @Periokiex) were used

- Logs date from 19/09/19 to 13/10/19

1:24 AM Batch 4 27/09/19

BTUniverse Permutation 1

When MasterBeat and I profess our love for V (taehyung), Najarvie picks up Tata (V's plush persona) and moves towards me. Meanwhile, Evulute continues emoting Blackpink dance moves. Najarvie, who has been silent all this while, communicates through his actions. He picks up an extra Tata plushie and hands it to MasterBeat and Evulute, both of whom are V fans.

1:31 AM Batch 4 27/09/19

BTUniverse Permutation 1

MasterBeat and Evulute discover the markers and use them to spell out BTS. I interrupt MasterBeat mid-drawing to ask where he's from. He replies that he's from the Philippines. He then grabs an eraser and erases what he deems as mistakes.

1:40 AM Batch 4 27/09/19

BTUniverse Permutation 1

MasterBeat goes on to trace the silhouettes of both me and Boywithluv. The action isn't unlike what we've noticed thus far - building shrines around people. He then moves to V's poster and writes V at the bottom. He doesn't do this for the rest of the members.

2:13 AM 27/09/19 Rest and Sleep

I teleport to my friends Promocat and Freal Luv when everyone leaves BTUniverse. They are in deep conversation about how easy it is to form relationships here, mostly due to the lowering of social inhibitions, a confirmation of the 'anonymity-breeds-intimacy' concept perpetuated by media theorists. The conversation quickly moves to employment woes. Freal Luv admits his disillusionment with his major in fashion design, though he's completed his Bachelor's, remarking that he might be more interested in game development. PromoCat, still a student, says he comes to the virtual world to escape the banality of university life. I understand.

We enter the world too see many friends on first floor, huddled together hanging out. However, we notice that Promocat and FrealLuv (the usual life of the party) aren't there. I go to the second floor to notice both of them alone at hot tub, having a heart-to-heart conversation about why Promocat decided to join this platform and his struggles in the real world. warm lighting, starry sky and soothing music the second floor (roof terrace), along with the intimate setting of the hot tub seems like the perfect setting to hold such conversations.

2:32 AM 27/09/19 Rest and Sleep

The topic swings to hopes and dreams after Freal Luv tells PromoCat to keep his head up and look towards a happy future. It's heartwarming advice. PromoCat says his dream is to set up a Youtube channel after mastering the guitar. His ultimate dream leaves me a little stunned - he wants to meet everyone (in real life) he's been able to vibe with online, including me and Perrine, vlog his experiences, and post it on Youtube.

2:44 AM 27/09/19 Rest and Sleep

Two new users join us from downstairs, saying they're here to escape the noise. The onsen setting adds to the peaceful ambience. Since Freal Luv is a fresh grad, while the rest of us are all students, we start talking about student exchange experiences. I tell them about my Shanghai experience. One of the foxes elaborates on his experience in Taiwan. The ease and speed at which we've found a new topic surprises me. It usually takes a while to assimilate new users into the group.

on the FrealLuv up alone conversation The music on the the

*The 7 members of BTS are V, Jimin, Suga, Jungkook, J-Hope, RM, and Jin. Their equivalent characters in BT21 are, respectively, Tata, Chimmy, Shooky, Cooky, Mang, Koya, and RJ.

PERMUTATIONS OF BTUNIVERSE

Subjects | A blinded experiment was carried out on an average of 40 users per permutation, made to experience the modifications across BTUniverse Permutations 1 to 4 over a period of 2 months. Thse 40 users were segmented into batches, or groups, based on observation of group activity, amounting to 3 or more batches per permutation. Each batch consisted of at least 3 users. In any batch, users consist of either solely fans, or a mixture of both fans and nonfans, with non-fans being a minority user group.and recorded after each modification.

(e.g. floor area,

after each

because such

strong

In

PERMUTATIONS OF BTUNIVERSE

enabled’ in the legends) and its

and their eventual

(Sphere of Influence, drawn from the greatest radial distance between the original

of the

At

and

. For example, were there tables that users might have perceived as too

were there tables that users might have perceived to be overly 'spacious'?

and

chose not to

of

there?

Key Ratios and Definitions

Wp (min.)/Wa (min.) = width of primary object facing minimum width of adjacent object (minimum)/ width of adjacent object (minimum)

Wp (max.)/Wa (max.) = width of primary object facing width of adjacent object (maximum)/width of adjacent object (maximum)

H p/Hn (min.) = height of primary object/height of nearest object (minimum)

H p/Hn (max.) = height of primary object/height of nearest object (maximum)

D(min.) = distance to nearest object (minimum)

D(max.) = distance to nearest object (maximum)

D = distance to nearest object

H n = height of nearest object

W a = width of adjacent object

Permutation

Purposee

Permutation

To find an optimal range of ‘enclosure rankings’ suitable for the function of sitting (or resting), based off user selection of perceived ‘enclosed’ spaces in BTUniverse.

2,400.00 2,100.00

Methodology

Permutation

3,300.00 3,300.00

Calculation of ‘enclosure rankings’* | A total of 6 boundary variable scores were compounded together to produce a ‘total score’ that would dsetermine the ‘enclosure ranking’ of each space with respedct to the primary object. A ‘range’ of optimum ‘enclosure rankings’ would then be determined via tables where instances of group activity (minimum of 3 users resting/sitting) occurred.

*Based on the H/D ratio in Hayward and Franklin's (1974) paper on the Perceived Openness-Enclosure of Architectural Space.

Permutation 3 Steps [Used] 1,350.00 6,245.00 7,000.00 0.00 260.00 1,400.00

(Least enclosed)

Permutation 3 T8 [Unused] 1,000.00 2,400.00 2,100.00 0.00 3,100.00 940.00

Permutation 2 T4 [Used] 1,000.00 2,400.00 2,100.00 0.00 3,400.00 1,055.00

Permutation

Permutation

(Most enclosed)

Boundary variables (coloured boxes)

10 Score

Wp (min.)/Wa (min.)

Wp (max.)/Wa (max.)

All variables were dimensioned for each space, in relation to a primary object. The maximum and minimum within each variable, across all spaces, were then used to produce individual scales with steady increments/decrements for subsequent ranking and calculations.

E.g. for D(min.)/mm,

1. Maximum distance = 1500.00

2. Minimum distance = 0.00

AND SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

more

Optimal

also presents evidence that

refer to an external booklet labelled

of

for

of virtual alternative

on how to construct optimal rest

is still very much

who wish to include

may refer back to the corresponding

and

Permutation

Permutation

[Unused]

Permutation

Permutation

[Unused]

[Used]

Permutation 3 T10 [Used]

2,400.00 2,100.00

2,400.00 2,100.00

2,400.00 2,100.00

3,300.00 3,300.00

3,100.00 2,400.00

4,140.00

3,250.00

2,240.00 1,035.00

Permutation 3 Steps [Used] 1,350.00 6,245.00 7,000.00 0.00 260.00 1,400.00

Permutation 3 T8 [Unused] 1,000.00 2,400.00 2,100.00 0.00 3,100.00

Permutation 2 T4 [Used] 1,000.00 2,400.00 2,100.00 0.00 3,400.00 1,055.00

Permutation

Permutation

[Unused]

2,100.00 3,000.00

2,100.00

4,000.00 0.25

4,000.00 0.25

4,000.00 0.25

4,000.00 0.24

2,340.00 0.58 4,000.00 0.34

4,000.00 0.25

Dynamic gimmicks and their extent of influence (SOI)

Respawn point and the crafting of isovist views

Correspondence between

Proxemics and the Distance in Virtual Man

four distances of

Hall’s (1990)

the distances in man. In his book, The Hidden Dimension, he posits that every individual has situational personalities associated with responses to initimate, personal, social and public transactions. Chapter X on “Distances in Man” quantifies each distance zone and provides in depth descriptions on each of them.

exist

our experiment, 56 user goups were categorized into no. of users and subsequently colour coded according to distance types. The users were observed to have situational personalities with regards to initimate, personal, social and public transactions, similar to that of non-virtual interaction Hall described.

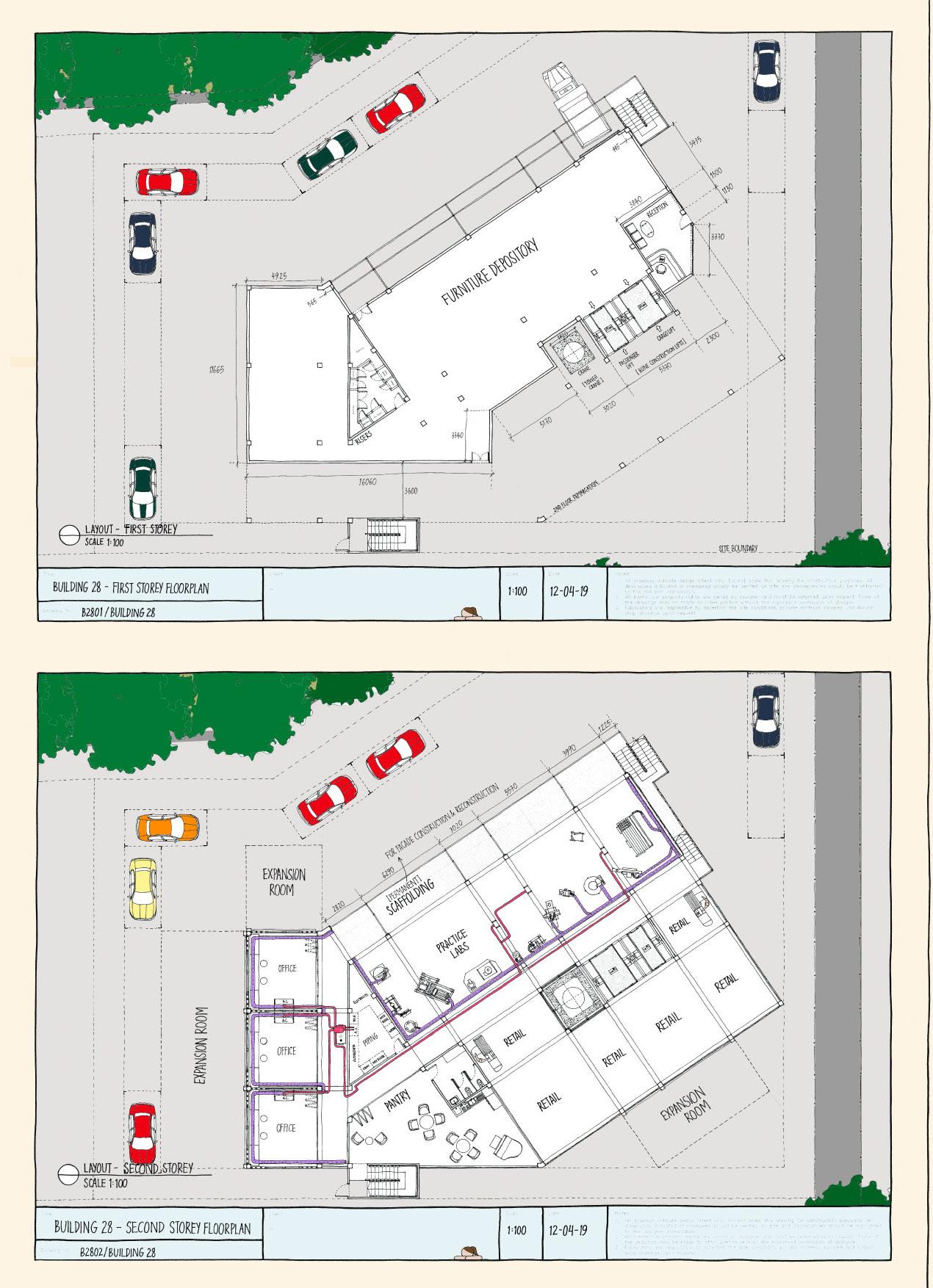

IN the year 1943, Building 20 was hastily erected as a temporary extension to Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), a three-floor combination of cheap plywood and gypsum boards. Despite the unending complaints from its inhabitants about creaky floorboards and dimly lit interiors, the building served as a "magical incubator" for research programs and innovation up until its demolition in 1988, for the temporal nature of the building meant that incumbent researchers felt free to modify interiors at will, accommodating sudden spurts of innovation. Researchers created holes through floors to accommodate huge equipment, ran wires across labs, broke down lab walls for inter-disciplinary collaborations - changes which later birthed modern linguistics and grammar and the world's first atomic clock.

Building 28, a play on Building 20, hopes to create this culture of innovation through transient architecture and modifiable rooms, bringing the spirit of Building 20 back to life. Here, customers bring their used furniture to recycle at the Practice labs, a safe space for them to destroy and re-purpose items; firms innovate in their Offices and test public reception to their products via the Retail section, free to collaborate among themselves due to their modifiable office spaces. In short, Building 28 aims to be an incubator and safe space for product design, as well as a revolutionary retail experience for the public.

Semester: Y3S2 (National Univeristy of Singapore) | Project type: Individual Software used: Photoshop, InDesign, AutoCAD, Rhinoceros, Grasshopper

THE FUTURE OF RETAIL: ASSEMBLY-LINE SHOP SPACE

Continuing Drucker’s theory, the future of retail would evolve based on consumer-brand relationships. Given the declining environmental climate, we can assume the resources would eventually be limited. Luxury fashion would have to be made sustainable through manufacturing on consumer demand and consumer personalization. What this entails is increased consumer involvement, meaning that consumers would be heavily involved in the design of their clothes and its concomitant manufacturing process. By way of the fact that consumers pay for the craftsmanship of luxury, they should be privy to the processes behind what they paid for.

This millennial trend gained traction with the promulgation of videos depicting ‘satisfying’ completion of tasks by people who possessed skilled precision. This was said to be extremely calming for perfectionists and people with Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, even if one lacked interest in the type of skill displayed. This fact will be capitalized upon in creating an immersive experience within the Atelier théâtre, regardless of one’s interest in fashion.

CONTEXT

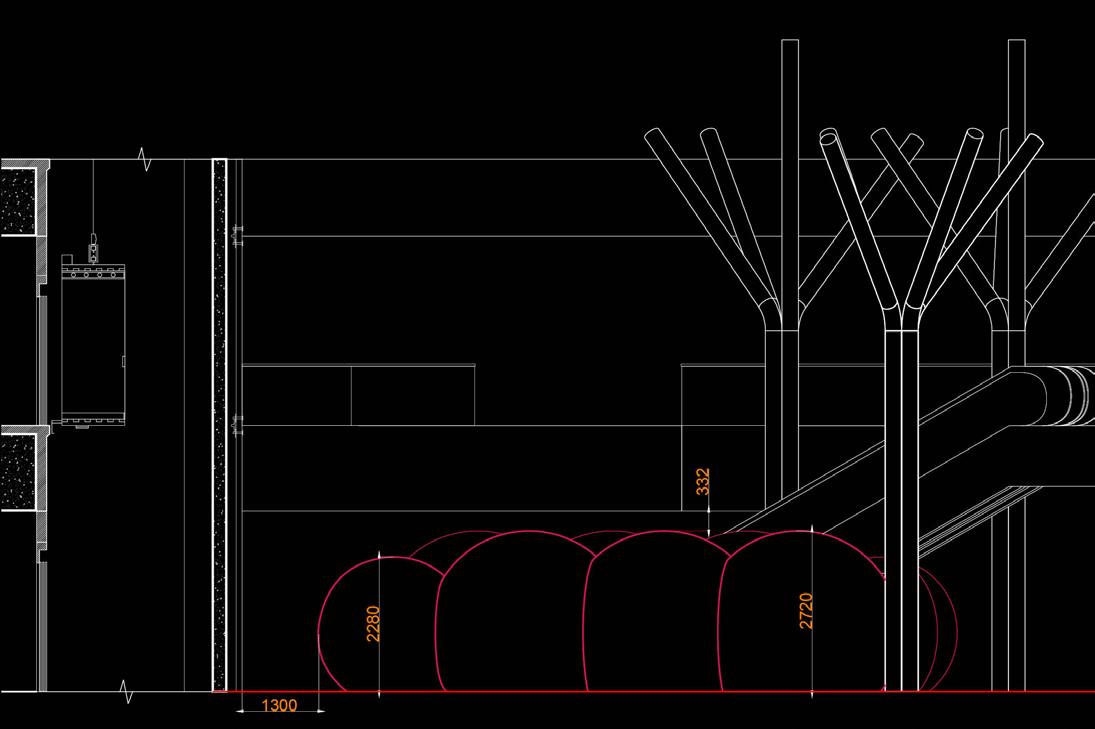

AMPLIFICATION OF SOUND WAVES

The pavilion’s assigned site was the K11 building, an art mall located along Xintiandi, Shanghai. Within the K11 mall, this project’s chosen site was located in the atrium of B2, based on consumer circulation and the level of noise, for the atelier had to provide the appropriate ambience for a completely immersive theatrical experience.

In 1931, the inventor M. R. Hutchinson invented a apparatus that could amplify sound waves within the space between two alternating arrangement of ‘teeth’, or ‘sound reflectors’. Within this space, sound would be rebounded off the walls continuously from sound sources to the end of the apparatus. This method was said to transform the apparatus into a veritable sound cave. This project utilizes a similar method to amplify the sounds of machinery whirring, tissue packaging, the shearing of fabric, and more. The concept drawing on the left depicts an envisioned scenario of the travelling sound-waves, beginning from the tables where the seamstresses sit, rebounding off the different concave walls to produce acoustic hotspots along the axis of the pavilion.

BEHOLD ATELIER théâtre, an immersive theatre experience combined with the craftsmanship of luxury retail. Through this experience, consumers are treated to the entire process of how their goods are made, starting from their selection of designs, all the way to the careful packaging of what they ordered. Along their path, they are treated to videos of the exact skills being projected behind the seamstresses - in perfect juxtaposition with reality. In other words, what you would usually see only on screen is now manifested threedimensionally before your eyes.

THE demolition of structures requires energy, manpower, and generates a horrific amount of noise and air pollution. Material

Cordoned off by authorities, this inefficiency and wastage goes unnoticed by most civilians. The deliberate retardation of the demolition process, along with the concomitant regeneration of the structure exposes ordinary civilians to the realities of the process: material wastage, pollution, and hard labour - all while minimizing health risks through passive design strategies. The repurposing of the materials from the old octagonal warehouse reduces the amount of energy loss through material wastage.

When demolition begins, the

at

process of

is also produced in the form of

to the

Site Plan: Kallang Industrial Site | As of 2018, the hexagonal warehouses were slated to be demolished in 5 years' time. they were then chosen as ideal test beds for the process of 'creative destruction', or slowed-down demolition.

Elevation

Plastic and timber was to be sourced from the junkyards of the industrial park... ...While concrete and masonry derived from the demolition were re-purposed for the construction of the museum and eventual center for re-purposing old materials. steel

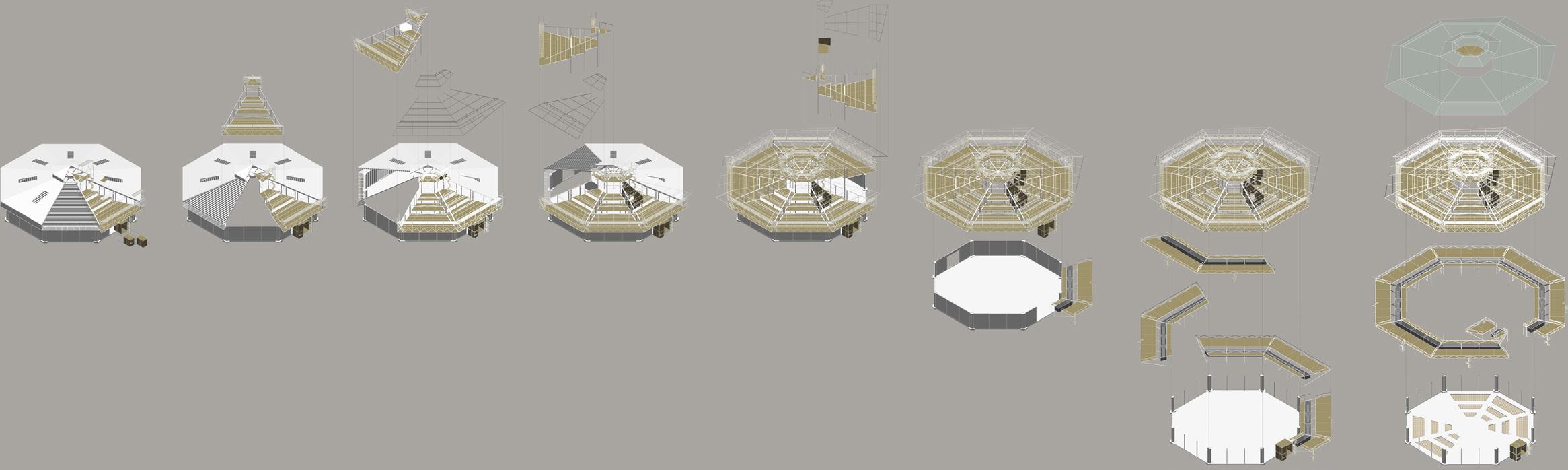

REDEFINING THE DEMOLITION PROCESS

Demolition is typically seen as both a ‘loss of substance (in this case, a building)’ and ‘a possibility to create something new’ – a champion of ‘creative destruction’ that proffers a potential economic gain. However, the process incurs an enormous amount of material wastage in the form of demolition debris, most of which are sent to landfills to be processed. The amount of energy lost through demolition is naturally and unnecessarily high, given the speed at which buildings in Singapore – and most of the modern capitalist world are demolished.

This project approaches environmental awareness and sustainability using a methodology that circumvents and attempts to improve upon the traditional demolition narrative. In other words, the process of demolition is redefined for a single octagonal typology. Traditionally, the warehouse typology is demolished in structural sequence with machinery: the corrugated steel roof, followed by the steel purlins holding up the roof structure, then the masonry brick walls (consisting of masonry brick and reinforced concrete), and finally the supporting load-bearing concrete columns and subsequently, the concrete floor. The rate at which the structure is demolished via machinery typically takes up to a couple of days, given that the warehouse stands at approximately 6 meters tall.

For my project, the demolition process is lengthened and stretched out to approximately 3 months per phase in order to conserve material usage and concomitantly preserve material energy. The materials torn down during demolition are re-processed via machinery and used during the in-situ construction of the new structure. This construction will take place alongside the demolition process, while the demolition process will take place in a way that happens sequentially and segmentally, clockwise around the original octagonal typology.

Annihilation still defines the end state, yet the process, lengthened as it may be, morphs into something educational and ceremonial. The maximization and exploration in this project redefines demolition, transforming it into something artful, drawn out, and almost celebratory.

As the warehouse is demolished, materials are re-purposed and reused in the construction of a new building - a new center for the recy cling and re-purposing of old furniture and materials, as well as a bittersweet reminder of its past.

First five phases | For every segment of the corrugated steel roof and its supporting steel structure that is torn down (refer to left-most isometric drawing), a segment of the new structure is constructed using the torn-down materials. For the first 6 phases, only the roof is being replaced, which consists only of corrugated steel sheets and steel purlins. The corrugated steel sheets are melted and re-cast into 50 mm by 50 mm steel members, while the steel purlins are simply dismantled and reassembled to form the steel columns and members of the new segment (joined by welding). The floorboards are made of timber obtained from the demolition of other buildings within the Distripark.

DEMOLITION SEQUENCE

Last three phases | The same concept applies to the brick masonry walls, which are demolished in the following order: the exterior brick cladding layer, followed by the concrete in-fill layer, and subsequently the rebar gridwork. Replacing the original aforementioned components of the warehouse are platforms made of timber, a supporting steel frame structure comprising 50 mm by 50 mm steel members, as well as concrete crushing steel machinery for repurposing the concrete that has been demolished. The segment will be appended to each edge of the octagonal warehouse structure as the walls are being demolished. The concrete and brick masonry walls are processed into concrete and brick aggregate respectively, which then can be used in the repurposing workshop activities taking place in the structure.

FUNCTIONS

Workshop Areas

Workshop Areas

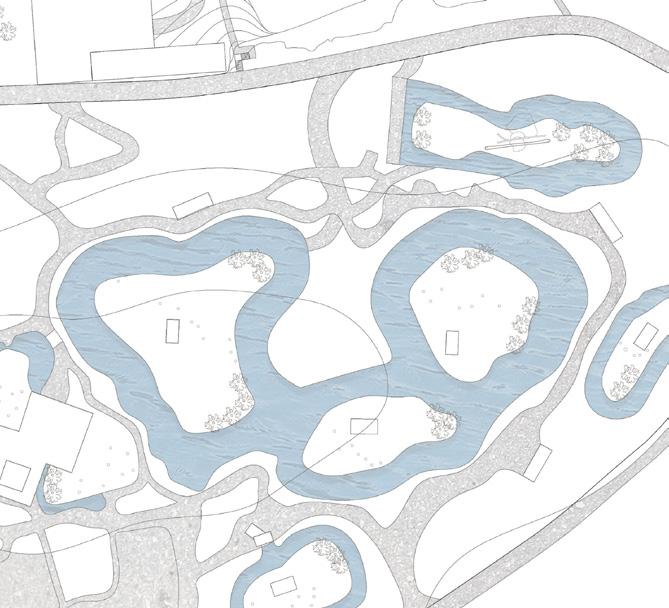

THEaim of this project’s design brief was to re-interpret the concept of an eco-lodge and successfully translate it into a form that could be used for camping with a certain level of comfort. What I had initially noticed about Mandai Zoo was that there were obvious barriers, either tangible or intangible, that defined the relationship between human and animal. Humans were given the role of the clear dominant, while animals were the clear subdominant or captive species. This has led to the formation of a hierachy that always ranks humans above animals. The resultant psychological effect in these animals is that, barrier or not, they would intentionally place a distance between themselves and the human species, because humans rank higher in the social dominance hierarchy.

My design intent sought to mitigate this effect and reshape the levels of dominance between primates and humans, with primates being the species of choice simply due to the Darwinist similarities in both species. Through an inverse in the relationship, the opposite effect could arguably be achieved, in which animals start to perceive themselves as higher up in the dominance hierarchy as opposed to the usual anthro-zoological interaction predetermined by zoos. The less fear that animals have around humans, the less they shy from interaction, which could potentially lead to a possibility in the coexistence of the 2 species within the same habitat. Over the course of the project, I have come up with 4 design parameters or spatial rules that shape my design process and translation of my concept: (1) Domination through Hierarchy; (2) Domination through Territory; (3) Domination through Ease of Accessibility to Food; (4) Domination through Ease of Navigation.

Semester: Y2S1

Software used:

Site: Mandai Zoo, Singapore

A. Area of Interestprimate enclosures

Ferry Routes

Tram Routes

Colobus

2960 (Horizontal distance to maintain average personal space for primates)

2960

(Vertical distance to maintain average personal space for primates)

5000 (Horizontal leap distance**)

5000

(Vertical leap distance**)

SPATIAL FACTORS

(1) Domination through Hierarchy

(2) Domination through Territory (Emphasis on human’s territorial constraint as opposed to monkey’s freedom of territory)

(4) Domination through Ease of Navigation (of primates over humans)

1050 (Span of a monkey's arm length - spacing of rods tailored to monkey locomotion)

To ensure safety of humans:

*Horizontal distance beyond which primates would be too intimidated to leap

***Vertical distance beyond which primates would be too intimidated to leap

Dining/Feeding Deck | Accessible to both primates and humans Least accessible place to humans Room for more dominance levels set by self-determination or negotiation between the 2 species

Dining/Feeding Deck

Kitchen/Bedroom/Washer Circulation Spaces

W.C. (Concealed from primates)

Negotiation Space (Accessible by both) - compromised platform for struggle of dominance between species

Human-only Platforms - subtraction of domination through ease of navigation All 4 Criteria fulfilled - highest level of dominance (for primate species)

FUNCTIONAL DIAGRAMS

(Left to right)

Confronting the Postfeminist Media Urban-scape: (How) Should Bodies Perform Femininity in Public Space?

18.3.22 Rachel Sim Jing Xi University of CambridgeAbstract Postfeminist outdoor advertising has become a pervasive phenomenon in the 21st century, inhabiting not just ‘feminized’ con sumer spaces such as shopping streets and major commercial intersections, but mundane, everyday spaces such as urban furniture and public transport stations. Yet few scholars have evaluated this phenomenon explicitly in relation to these spaces; in contributing to feminine anxieties and reinscribing the public/private divide in the city. This essay argues that the rhetoric of women’s fear in the city produces and is produced by the mutually constitutive relationship between postfeminist outdoor advertisements and female consumer spaces. Noting the significance of female (bodily) representation for feminist activism in the public realm, the essay further uses the Guerrilla Girls as a point of inquiry into an alternative mode of representation, analysing how their active disappearance, or conscious refusal to participate in visibility in public space, can function as a legitimate mode of tactical activism.

Keywords postfeminist outdoor advertising, female consumer spaces, ‘scary city’, Guerrilla Girls, active disappearance

Introduction

“One of the most striking aspects of postfeminist1 media culture”, says Rosalind Gill (2007: 149), “is its obsessive preoccupation with the [female]2 body.” The body, relentlessly policed by both men and women alike, has constituted a wealth of media content since the nineteenth century, often accompanied by excoriating comments: “in 10 months Billie Eilish has developed a mid-30’s wine mom body”, or an insulting “Who’s The Dad?” caption adorning a magazine cover of Taylor Swift with a slightly rounded belly (Fig. 1; Daily Mail 2016; GamesNosh 2020). Such comments, albeit referencing celebrity bodies, are symptomatic of the wider scrutiny of the way women are expected to present themselves in the city3, which in turn determines whether they are deemed acceptable to be seen in the public realm. This ‘reality’, uniquely experienced by women, is what feminist geographer Leslie Kern (2010: 210) aptly terms the “scary city”, a place that is equal parts excitement and danger, continually reproduced by postfeminist outdoor advertisements and the (public) consumer spaces they inhabit. Both constitute each other, propagating variations of ‘correct’ female selves that if successfully emulated, could allow women to freely traverse the city while mitigating their fears of being rejected from public space. Within this strategy, tropes that might previously have been perceived as ‘sexist’ and for the heterosexual male gaze – billboard models proudly displaying their sexual power, for instance – are visibly reconstructed as exhortations to feminine self-confidence, inadvertently reinforcing the “gendered public/private [male/female] divide” that has historically influenced how women are perceived in public space (Gill 2007: 151-2; Gill and Orgad 2017: 19; Arnold 2021: 572-3).

However, after nearly three decades of analysing the spatial effects of postfeminist outdoor advertising, scholars positioned at the intersection of feminist geography and media theory, such as Winship (2000) and Arnold (2021), have largely posited postfeminist bodily representation as a feminist reclamation of the city, themselves falling prey to the media’s aestheticization of female selfpolicing. Additionally, with the exception of Kern (2010), no scholar has commented on the mutually constitutive relationship between outdoor advertising and female consumer spaces; geographers such as Bondi and Domosh (1998), Bondi (2005) and Dreyer and McDowall (2012) have discussed the gendering of consumer spaces as female, yet none have made explicit references to the overwhelming visuality of female bodies in outdoor advertising despite its ubiquity since the 1980s. Kern herself has also not considered more mundane, everyday advertising sites such as train stations and pedestrian streets as consumer spaces, locales that

1 The term ‘postfeminist’ is not taken in this essay to be an analytical perspective. Rather, postfeminist media culture is taken to be a “circulating set of ideas, images and meanings” characteristic of post-1980s media imagery (Banet-Weiser et al. 2020: 5).

2 Historical discussions of women’s roles in public space typically define women as white, heterosexual, and of middle-/upper-class, simply because these were the women that were deemed acceptable to appear in the public realm (Bondi and Domosh 1998: 270). In this essay, beyond explicitly historical discussions, the woman can be defined as LGBTQ/heterosexual, coloured/white, able-bodied/disabled, etc.

3 The urban context in this essay is primarily Euro-American, as well as developed nations outside of that context, such as contemporary China, where consumerism has come to define women’s identities to a large degree (Ferry 2003: 285-7).

Cronin (2006: 618-23) maintains should be considered given that they mark the “routine experience of traveling to and around cities”, and therefore have frequently been exploited by advertisers to increase female consumption.

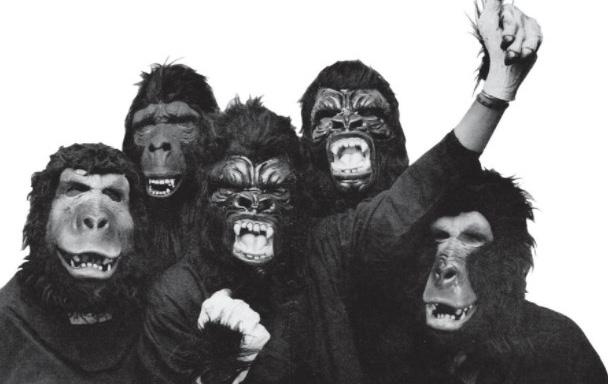

This essay thus aims to explore how the rhetoric of women’s fear in the city reinforces and is reinforced by the mutually constitutive relationship between postfeminist outdoor advertisements and female consumer spaces, thereafter reinscribing the public/private divide. Sub-section I(a) draws parallels between the textual analysis of postfeminist advertisements (1990s and post2000) and feminine anxieties in the city, while I(b) embarks on a more urban/historical analysis of how consumer spaces (e.g., major shopping districts and commercial squares) and certain everyday spaces came to be coded private/female as a result of the modern city, eventually constituting postfeminist advertising sites and reproducing the anxieties elaborated upon in I(a). Additionally, in line with Judith Butler’s (2014: 110) assertion of the need for the female body to appear or be represented in a way that “avoids the retrenchment of paternalism”, section II asks how female bodies can alternatively be represented in public space as a form of feminist resistance, using the case study of the Guerrilla Girls, an anonymous feminist artist collective who employ flyposting in the public spaces of New York City (NYC), London, Los Angeles and more. When appearing in public, they don gorilla masks and adopt the pseudonyms of dead female artists, quite literally re-skinning themselves as “jungle creatures” to de-sexualize themselves (Flanagan et al. 2007: 6). Through the lens of Peggy Phelan’s (2005: 19) writings on “active vanishing”, that is, the “deliberate and conscious refusal to [participate in] visibility” in the public realm, I seek to articulate how the Girls perform bodily resistance to subvert gender roles in the public sphere.

(Left Column) Fig. 1. (top) Billie Eilish’s ‘wine mom body’; (bottom) “Who’s The Dad?”

(Right Column) Fig. 2. (top) Think of her as your mother, American Airlines, 1968; (bottom) ‘TOTAL’ watches your vitamins, while you watch your weight, General Mills, 1970

I. Commercial Strategies: Postfeminist Female Bodily Representations and the Reinforcement of the Public/Private (Male/ Female) Divide

I(a). Feminine Anxieties in the City

Contrary to what the contemporary feminist may think, the pre-1970s media urban-scape was not worlds apart from the one today. Replacing the overtly sexist advertising campaigns of the ‘50s and ‘60s – American Airlines coaxing the male public into perceiving beautiful, lithe flight attendants as their mothers in 1968, or General Mills telling females to “keep up with the house while [they keep] down [their] weight” with vitamin-packed cereal (Edwards 2015; Fig. 2) – are a dizzying array of postfeminist campaigns celebrating the ‘confident, empowered’ female subject (Gill and Orgad 2017: 19). Notably, they engage tantalizingly with women’s desire to freely explore the “scary city”, that is, the city whose excitement is in part (paradoxically) generated by danger and anxiety (Kern 2010: 210). There have been differing interpretations of this ‘anxiety’; geographers such as Valentine (1989: 386) and Rosewarne (2005: 70) attribute this to men’s harassment of women in public space, which gradually “becomes associated with the [urban] contexts in which they [take] place”, exaggerated by the more frequent usage of female (than male) bodies in sexualized outdoor adverts. Others such as Bondi (2005: 9) and Kern (2010: 210) herself have instead drawn parallels between discourses of urban revitalization and gendered imagery: just as revitalization is designed to exclude “a dangerous urban ‘other’”, postfeminist portrayals of women present the city as “feminized and empowering for women”, but also with the “ever-present threat” for the woman who chooses not to present herself in such a manner. ‘Anxiety’, in this case, is associated with the fear of appearing as the ‘other’, a female body lacking certain desirable dispositions, unequipped with trending commodities or possessing non-normative traits in public space (Gill and Orgad 2017: 19).

Advertisers engage with both definitions, drawing on women’s innate desire to experience the thrill of the city by conspicuously featuring or ‘intervening’ in urban streets. In The Sphinx in the City, Elizabeth Wilson (1991: 30) recounts the “elation and pleasure” experienced by Lucy Snowe, the heroine of Charlotte Brontë’s Villette (1853), as she adventured alone in London, feeling as though she had never properly “felt London” before she “dared the perils of [road] crossings” and sunk herself into “the heart of city life”. Such a primal feeling was indubitably rooted in the post-industrialist (albeit white, middle class) division of labour, in which women tended to domestic matters, while men headed out into the public realm and took home the wages (LaFrombois 2018: 17-8). Consequently, the cult of the walking man remains one of the most salient aspects of nineteenth-century scholarship: “the dandy, the flâneur, the hero, the stranger”, all invariably male figures conceptualized to encapsulate the experience of modern life’s ephemerality (Wolff 1985: 41). Men had the freedom to appear anonymous in public as they frequented cafés and pubs, while women, who were just only emerging into work and public spaces, were attended by men’s anxieties and so were prescribed certain ‘regulations’: they could appear in public only as phantasmic fetishizations for the male gaze (1985: 42-3).

Postfeminist bodily imagery are emblematic of and capitalize on this urban imaginary, positioning itself at the nexus of women’s desire to freely traverse public space and the fear of being objectified by the male gaze, offering the urban female streetwalker a way to construct an alternative, empowered identity for herself in relation to the city (Kern 2010: 210; Bondi 2005: 9). This rhetoric was widely taken up by advertisers in the 1990s, who depicted women claiming their freedom in the city with their sexuality, through which they could ‘overcome’ their fear of potentially being harassed by men in public space. In Wallis’ Dress to kill (1997; Fig. 3) advertisements, for example, the female subjects are seemingly indifferent to the male gaze. She in Crash leans over the railing and stares out into the horizon, causing the undoubtedly male driver in the background to crash his car, while in Barber, a woman in a bodycon mini dress nonchalantly swings her purse as she notes, through the corner of her eye, that the barber within the shop, entranced by her sexual power, is precariously close to slitting his customer’s throat. To borrow Laura Mulvey’s (1975: 12) psychoanalytic account of the male gaze, in each of the scenarios the men are ‘trapped’; the male spectator “projects his look on to that of his like [the driver/barber]” only to find himself immobilized and unable to exact control over the events. The usual “active/passive [male/female]” narrative structure conventionally employed by films is subverted as the woman, exuding ‘power’ and ‘confidence’, relishes in her freedom to roam the urban streets.

The woman “kills”, according to Winship (2000: 36), and we, the female audience, discover a new way of self-construction through identification with her. Or do we? This trope was also utilized in Wonderbra’s Hello Boys campaign (1994; Fig. 4), which despite not explicitly featuring the urban streets, ‘intervenes’ in it and engages the urban streetwalker. The imagery of lingerie-clad Eva

Herzigova, averting her eyes and smiling coyly, knowingly goads the male observer’s gaze with the power of her sexuality; what happens next could be interpreted as a successful confrontation by the female subject – men trying to regain control by splattering cement on “the danger zone of [her] breasts” (2000: 43). Through self-identification, the female subject discovers that she too can subvert her own fetishization by harnessing her sexuality on the urban streets, a visual mode of self that consequently empowers and enables her to freely venture the city. However, the very stylization of female subjects in these adverts still reproduces ‘submissive’ behavioural archetypes often employed throughout the long history of gendered imagery (Fig. 5), much like Herzigova’s “head/eye aversion” and coy smile in Hello Boys, or the Wallis woman’s arched back and seductive walk in Crash (Goffman 1976: 63; Arnold 2021: 582), inadvertently pandering to the male gaze in public space. The postfeminist era rebrands these inherently sexist tropes under the guise of female autonomy, which is in turn predicated on the female assuming a ‘confident’ self with consumer power and the body type of a white, lithe woman.

This notion has persisted even in more recent campaigns depicting supposedly ‘healthier’ and more ‘intersectional’ forms of representation, despite seemingly being transformed by the new visibility of plus-sized, African American, and LGBTQ bodies. Both Dove’s Real Beauty (2004; Fig. 6) and Lane Bryant’s #ImNoAngel (2015; Fig. 7) campaigns depict this “glossy diversity” – ‘real women’ such as model Ashley Graham and actress Amber Riley championing ‘body positivity’ and confidence, contradictorily reiterating that a particular plus-sized or African American body is accepted into public space (Banet-Weiser et al. 2020: 14; Draguca 2019). Thus, while such representations do shy away from the more explicit 1990s ‘harness your sexual power’ rhetoric and visual references to the male gaze, they similarly hinge on the idea of presenting a certain self, along with the bodily results of their consumption, to others in the public realm. The very (ubiquitous) presence of these advertisements within the city propagates the fear of presenting oneself as otherwise in the public sphere, inducing within women a self-policing, narcissistic gaze through which the public/private divide is reinscribed (Gill 2007: 151-2).

(Top Row) Fig. 3. (left) Crash, Wallis, 1997; (right) Barber, Wallis, 1997 (Middle Row) Fig. 4. Hello Boys, Wonderbra, 1994 (Bottom Row) Fig. 5. Goffman’s examples of the head/eye aversion, in Gendered Advertisements, 1976

(Top Row) Fig. 6. Real Beauty, Dove, 2004

(Bottom Row) Fig. 7. (left and middle)

#ImNoAngel, Lane Bryant, 2015; (right)

#ImNoAngel on public buses

I(b). Female Consumerism and the City

To gain a more complete understanding of the production and reproduction of the ‘scary city’, that is, how feminine anxieties have become so deeply entrenched into the public realm, the initial coding of consumer spaces as private/female and its subsequent association with postfeminist advertising sites must be discussed. As Lefebvre (1992: 71) writes, production requires an organization of “a sequence of actions with a certain ‘objective’ in view”, which necessitates the mobilization of spatial elements, both material (e.g., the city and its dimensions) and immaterial (e.g., advertising agendas).

First and foremost, it must be acknowledged that women were for the longest time denied a proper place in the public realm; by the likes of Aristotle, who defined women’s value to society by her domestic duties in the fourth century (Mulgan 1994: 184-6), to Baudelaire’s inability to view women as anything but objects of his gaze in The Painter of Modern Life (Wolff 1985: 42). Women’s later inclusion into public life was routed primarily through consumer activities and spaces, aspects that accompanied the rise of the modern city and the concomitant emergence of the middle class. In the postfeminist era, this has continued to dictate where advertisement campaigns are placed, in city locales presumed to be closely associated not just with women’s consumer habits, but also their daily routines as a subtle attempt to increase their consumption. These locales are routinized into everyday life, including residential complexes, transportation infrastructure and shopping zones, further conditioning the female streetwalker into her dual role as commodity (to be scrutinized) and empowered consumer (Cronin 2006: 622; Kern 2010: 220).

Many feminist geographers, such as Dreyer and McDowall (2012: 33) and Bondi (2005: 7), agree that women’s entrance into public life has been inextricably connected to commerce and consumption, with the latter scholar further remarking that this connection has reshaped public space since the second half of the nineteenth century, leading to the development of department stores and other consumer spaces in major cities. Bondi (2005: 7) maintains the creation of suburban housing, spurred by the urge to escape overly congested urban cores, cemented the middle-class ‘image’, where men’s wages were sufficient to support their non-working wives, and so enabled her to play the role of maintaining a stable household for the male head while he navigated the uncertainties of modern life, inadvertently reinscribing herself as commodity/property (Roberts 1998: 819, 825-6). The female’s emergence in the public realm thus came to be justified by the ‘politicization of the household’, where she could be seen in public on the condition that she was performing activities associated either with care, domesticity, or consumption, such as the purchasing of food and clothes shopping (Bondi and Domosh 1998: 270). Spatializing this rhetoric, developers ‘feminized’ the outdoors by designing streets that were replete with fashion stores, museums or art galleries; programs of consumption and leisure deemed to be appropriate for the feminine body. Those of Ladies’ Mile shopping district4 in NYC, for example, grew so popular that it “made it safe for women to go shopping unaccompanied by men for the first time”, their visibility in these spaces further reinscribing acts of consumerism and the spaces in which they were carried out as female (1998: 279; NYPAP).

To this day, postfeminist outdoor advertising-rich sites, such as spaces of revitalization or key shopping districts, remain unequivocally female consumer spaces. Kern (2010: 214-21), for instance, posits gentrified areas as neoliberal versions of ‘feminized’ city spaces; residential complexes or streets previously deemed too ‘masculine’ or unsafe for women, securitized and converted into veritable extensions of the private domain, fitted with “nice lobb[ies]”, a “twenty-four-hour concierge” or various cafés with “soft furnishings, fireplaces, bookshelves, small tables for intimate conversation, and a general sense of hospitality”. Rose (1989: 133) and Bondi (2005: 9) both note that such spaces, typically located in the inner city, grant women a way of managing domestic and employment labour, as well as increased accessibility to the experiences of modern life – relative anonymity and safety – while seemingly helping women mitigate feminine anxieties. Capitalizing on and contributing to this rhetoric, advertising campaigns within these locales portray women as empowered for being active, visible participants in local social and consumption activities, yet simultaneously predicating this on appearing in such ‘safe spaces’, dressed and looking a certain way (Kern 2020: 104-6; 2010: 225). This circumstance, albeit branded feminist today, recalls the nineteenth-century bourgeois woman’s experience of ‘feminized’ consumer spaces and thus hardly represents “a feminist reworking of [historical] gendered norms” in public space (Bondi and Domosh 1998: 280; Kern 2010: 225).

Additionally, mundane, everyday advertising sites organized around women’s “linear rhythms of work [and] commuting” in the city, while not all historically gendered female, also contribute toward retaining women’s experience of the city at the nexus of freedom and anxiety. According to Cronin (2006: 622-7), the company Clear Channel targets housewives by running advertising sites on “routes to (and within 1000 metres of) supermarkets or major [chains] (a third of sites are within 300 metres of these)”, including transport (buses, taxis, trains, train stations, etc.) and freestanding panels along shopping or pedestrian zones (Fig. 8). For various other female youth groups, these panels might be situated closer to high street stores (e.g., Zara) and universities. Such mapping strategies subtly persuade the contemporary female spectator to identify with postfeminist representations by the likes of Dove, Lane Bryant or more, who rhythmically reiterate that she maintains the right to be seen in public through consumerism. This urge toward self-identification is augmented by the large, ‘cinematic’ scale of certain adverts in cities, transforming each advertising site into a metaphorical cinema in which a false sense of “closeness” is fostered between the viewer and the adverts’ contents (2006: 625). Nigel Thrift (2008: 245) describes this phenomenon as a “transmission of affect”, where the outdoor adverts continuously exact an “affective force” to quite literally sap one’s agency not to look. In the opening credits of Sex and the City (seasons 1-4; 1998-2002), Carrie Bradshaw, clad in a pink muscle tank and tutu, struts on the streets of NYC, confident and free, only for a passing bus to cruelly splash rainwater all over her. Flustered and having lost her composure, she looks up and sees an image of herself plastered on the side of the bus, instantly looking away in fresh horror as the film frame freezes (Fig. 9). Against the backdrop of feminine anxieties, one has to ask, does her horror stem from being splashed with rainwater, or that she is forced to confront the visual disjunct between her undoubtedly more glamorous, sexual self in the bus ad and her flustered self on the sidewalk?

Served NYC primarily from mid-19th century into the early 20th century (NYPAP).

II. “Creative Complaining”: The Guerrilla Girls and ‘Invisible’ Representation

Certain political demands made by vulnerable bodies, such as their protection and mobility, “sometimes must take place with and through the[ir] bod[ies]” in the public realm (Butler 2014: 102). Given that the public visibility of the female body has functioned as the key medium through which space is gendered, it is unsurprising that many international feminist movements have witnessed women protesting through their bodies, from SlutWalks since 2011, to the Latin American Ni Una Menos movements since 2015. Certain movements, however, have demonstrated that women may be unaware of the risk of taking in – or worse, practicing –discourses framing postfeminist bodily representation as a liberating reclamation of female autonomy; SlutWalks, for instance, are symptomatic of women choosing to objectify themselves as an ‘empowering’ personal choice (Evans 2017).

Further, both Butler (2014: 110) and Phelan (2005: 10) lament the struggle to ideate all-encompassing representational strategies, acknowledging that it is almost impossible to represent the self adequately “within the visual or linguistic field”. The visibility of African American skin, for example, can never be an “accurate barometer” for representing what is “resistant to representation”, that is, her “diverse political, economic, sexual, and artistic interests” (Phelan 2005: 10; Banet-Weiser et al. 2020: 14). Kern (2020: 106) also asserts that physical mimesis promotes the ‘othering’ of women who fail to behave in normative ways, such as those

possessing “outward signs of trauma or mental illness” being asked to leave cafés along gentrified streets. For feminist resistances, then, there remains a need to explore alternative methods of representing female bodies in public space without reinforcing the spatial manifestations of paternalism, in order gendered norms might be temporarily reworked in the city.

The Guerrilla Girls are a feminist art collective who explain their conception by inviting you to “imagine [you are an] artist pissed off that almost all the opportunities in the art world go to white men” (Guerrilla Girls 2020: 5). “[N]o museum goer even cares!” They holler, further inviting you to “dream up a new kind of street poster to wake people up to the pathetically low number of women artists shown in galleries and museums”. Back in 1984, the glaringly disproportionate ratio of male to female artists at the Museum of Modern Art’s (MoMA) International Survey of Painting and Sculpture exhibition was the last straw, to which they kickstarted a street poster campaign targeting many institutions deemed perpetrators of women and non-white artists’ exclusion from the mainstream art scene. Adopting the visual language of “fly-posting”, they “[snuck] around New York in the middle of the night” the following year, lathering glue on the walls of SoHo and slapping posters – bolded, blocked-lettered statistical lists and art market prices – calling out sexist and racist policies influencing museum collections (Fig. 11). When appearing in public, they don gorilla masks and adopt pseudonyms from deceased feminist figures - writer Gertrude Stein, artist Frida Kahlo, and more (2020: 5; Tate; Fig. 12).

The Girls engage in what Phelan (2005: 15-9) calls an active vanishing, that is, a conscious refusal to participate in visibility. Pointing out the psychic paradox of Lacanian psychoanalysis (“one always locates one’s image in an image of the other and, one always locates the other in one’s image”), she observes its inevitable failure: seeing the self is negotiated through representation, yet the Real is never faithfully and accurately reproduced. “Saying [the whole truth] is literally impossible: words fail” (Lacan 1990: 3). Just as words fail, “eyes fail”; the eyes, searching for the self in the other (representation), similarly obscures the Real. The Real here is perhaps most succinctly defined by Foster (2003: 189-90): “a black hole […] of non-subjectivity”; in order to see the Real, we must shed the “illusions that mystify reality” (for example, the ‘scary city’ construct). Phelan (2005: 19) builds on Lacan, suggesting that since nothing will be depicted or read in a non-subjective manner, exploring the invisible – active vanishing – may paradoxically function as a way to reveal more of the Real. Using the Guerrilla Girls as a case study, the remainder of this essay is dedicated to exploring what it would mean to perform ‘invisibly’ in public space as a means of feminist tactical activism.