9 minute read

From Am Dram To Ambitious Drama

‘… acting just like a real play.’

On Whit Monday in 1857 ten-year-old John Godley had his first experience of a dramatic performance: it left him stage-struck. This was ‘acting just like a real play’, with a stage set up in the schoolroom (now the Library), great curtains, a grand piano, tickets, and costumes all brought from London. The play was Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part 1. Afterwards, John requested (and received) the complete works of Shakespeare for his birthday. William Sewell had introduced drama to Radley.

For Sewell, this was a part of the beautiful, Arcadian aspect of life at the school – an appropriate cultural and leisure activity associated with living in a country house. Educationally, through performing or reading plays and memorising speeches and poems to give as recitations, boys would become familiar with both Classical and modern European cultures. They would learn posture, voice projection, memory techniques and teamwork as part of fitting them for public life. But above all, they would have great fun.

The classics

From 1880 onwards, the whole school, and most Old Radleians, gathered at Radley for the annual All Saints' Day celebrations where, alongside a Chapel service, a concert, sports and a dinner, theatrical entertainments were put on. There were scenes from Shakespeare, Molière (performed in French during a period when the playwright’s works were seldom performed in France) and Restoration comedies but the highlight was the Latin play. These were produced from texts specially prepared for performance at Radley and printed for sale by Oxford University Press. Performance at Radley was something to be done properly.

From 1880 until 1897 four Roman comedies were performed in Latin in strict rotation: Andria, Phormio and Adelphi by Terence, or Trinummus by Plautus – on the whole, the school preferred Plautus.

After 17 years they branched out into a new repertoire: Aulularia by Plautus, and then in 1897 a group of the senior boys were taken into Oxford to see the Oxford University Dramatic Society’s production of The Knights by Aristophanes: ‘May we venture to say that none of us really appreciated a Greek play before we saw one actually put on the stage.’ (The Radleian, 1897). In response, the new century was celebrated by an excursion into Greek: The Frogs by Aristophanes, which went on to receive a full review in The Times of 3rd November 1900.

The specially adapted Latin plays were abandoned in favour of a mix of a new Latin play (Rudens by Plautus) and Greek comedies: Aristophanes’ The Wasps in 1905; The Frogs was revived in 1906 with Sir Hubert Parry’s music; Euripides’ satyr play Cyclops in 1908; and The Wasps again in 1911. All were performed in the original languages. Then followed five years of silence until in 1916 the Literary Society began an annual event: the reading of a Greek tragedy in the new translations by Gilbert Murray. In 1946, don Charles Wrinch reintroduced plays performed in Greek, beginning with Sophocles’ Electra

For the next 25 years, Radley produced a biennial Greek play which attracted reviews in The Times and enticed eminent academics and actors to view performances. The influence of Classical plays continues into the 21st century, although now performed in English, such as the Shells’ play of 2004, Tales from Ovid (Ted Hughes’ retelling of Ovid’s Metamorphoses), or Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex for the 2017 school play.

The play’s the thing

From 1924, Drama became the preserve of RCADS (Radley College Amateur Dramatic Society), headed by dons Kenneth Boyd and Charles Wrinch, and senior boys, with backstage support from members of the community.

From its foundation, RCADS aspired to be far more than a smalltown Am Dram group. They performed a wide-ranging repertoire which included Shakespeare and contemporary drama such as R.U.R. by Karel Čapek (1920), the Czechoslovakian play which introduced the word ‘robot’ into English.

Just as Wrinch’s Greek plays had a lasting influence, so did the fully staged performances of Shakespeare which far exceeded normal schoolboy productions. Boyd’s book, The Technique of Play Production, published in 1934, became a standard textbook for school drama departments across the country. National recognition of their work culminated in a five-day conference at Stratfordupon-Avon in 1953 about the role of Shakespeare in schools.

Peter Way joined Boyd and Wrinch in running RCADS in 1952. Way had been a member of the Society while a boy at the school in the 1940s and breathed new life into it for the next 28 years, beginning by introducing a new dramatic form to the repertoire: 17th-century masques. Examples included John Milton’s Comus in

Top: 1883 production of Molière’s Le Médecin malgré lui

Middle: 1906 production of The Frogs by Aristophanes, showing the orchestra accompanying the performance.

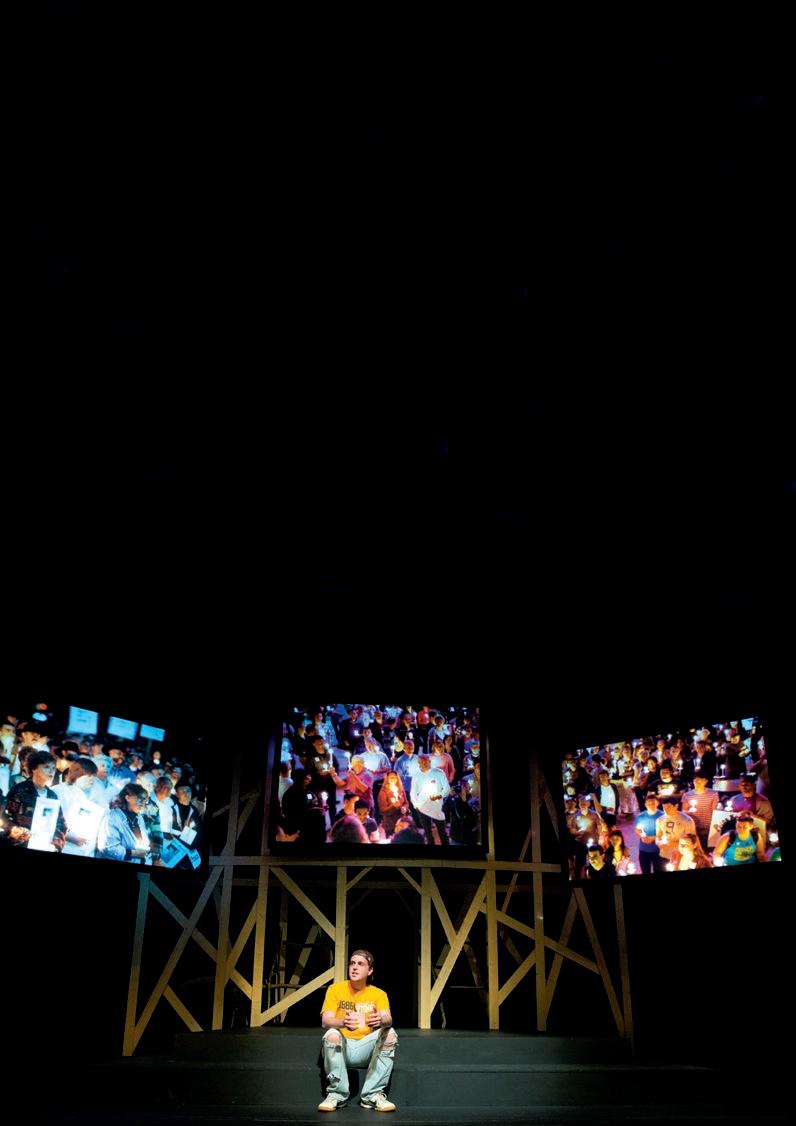

Bottom: 2017 production of Oedipus the King, starring Jamie Walker (2014, K).

1956, accompanied by the original music of Henry Lawes played on the harpsichord, and Way’s own composition Lusimasque written to celebrate the opening of the Arts Centre in 1979.

The most distinguished of RCADS’s productions during the 1950s were probably Christopher Fry’s A Sleep of Prisoners, performed in the parish church in 1955, and Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II in 1958. Edward II remains a highly controversial play. Its performance encouraged one teacher to apply to work at the school because it demonstrated such an innovative and bold approach to education. In 2023 Radley is still the only boys’ school known to have given a performance open to the public in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Radley plays would continue to be chosen from cutting-edge drama. Peter Shaffer’s Equus, performed in 1983 under Jim Hare’s direction, was charged with a sense of such fierce psychological danger that it was asked whether it would be safe for junior members of the school to see the production: ‘The answer was “no” and was probably right. For in Justin Grant-Duff’s boy and

Maurice Lynn’s Dysart there was an intensity that was frightening’ (Hamish Aird).

Robert Lowe, Director of Drama in the 2010s, also introduced a challenging repertoire of plays, particularly The Laramie Project in 2012, which, like Edward II, remains a controversial play for school performances: just three years before Lowe’s production at Radley, a group of parents in Nevada tried to get the play banned. He also oversaw an ambitious approach to Shakespeare, with several years devoted to a cycle of performances of the complete history plays from Richard II to Richard III. Cast members quickly added stage-combat lessons to their acting skills!

The most spectacular was Jim Hare’s own dramatisation of Piers Paul Read’s 1974 book Alive about the survivors of the 1972 Andean air crash, Maybe Tomorrow. The original play had a cast of more than 40. In 1992, Hare adapted his own script for a smaller cast of Radleians who took it to the Edinburgh Festival. In the early 1990s, Hare also wrote his own adaptations of the films Dead Poets Society and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest;

Features

the latter was also taken to Edinburgh. In this he was following a tradition already in place: Radleian Jonathan Griffin’s (1920) play The Hidden King premiered in the Assembly Hall at the Edinburgh Festival in 1957; while the introduction of Radleians to the Edinburgh Festival continued after Hare retired when Quadrant Productions, a troupe of four Radleians, took Frank McGuinness’s Someone Who’ll Watch Over Me in 1996, and James Walker (1992, H) took his one-man show Born to be Wilde (the story of Oscar Wilde’s eldest son Cyril Holland, who was at Radley) in 1998. In 2007, the Edinburgh Festival came to Radley, when Cambridge Footlights became the first visiting company to perform in the New Theatre.

Teaching theatre

RCADS came to a natural end with the retirement of Peter Way in 1980. Drama was changing, becoming a part of the curriculum, rather than an extra-curricular activity for a society, although there was still room for innovation and participation for those not explicitly studying the subject, while members of the community who had worked backstage continued to do so. The annual school play once again became an all-school production under the direction of newly appointed Jim Hare. He already had a distinguished career behind him as a director for the National Youth Theatre and as Head of Drama at Blundell’s School. In addition, he had a wide range of experience in other theatres including Bristol Old Vic and the Royal Shakespeare Company.

His innovation was to set up small studio-based productions as part of ‘additional subject drama’, alongside the major annual school play, and the continuing Drama Festival in which all the Socials took part. His first production at Radley, Tom Stoppard’s Dogg’s Hamlet, introduced the new 6.1 Drama Workshop. His first major play at Radley, Peter Shaffer’s The Royal Hunt of the Sun, took the College by storm and proved to be the first in a run of stunning productions: ‘It had many of the features of Jim’s productions as we came to be familiar with them: great visual power, a natural sense of space on the stage, seamless acting and a sense of danger. In The Royal Hunt of the Sun the danger lay in the massive wheeled tower that careered across the stage with Atahuallpa atop. No one had seen anything quite like this at Radley before’ (Hamish Aird).

The tradition of the Drama Festivals pioneered by RCADS from 1937 came to full fruition under Jim Hare with ‘additional subject drama’. These initiatives gave pupils room to grow not only as actors, but as writers, directors, producers, stage managers and designers. Short plays or films popped up all over campus: ‘Jim let his actors develop. When you were in trouble with a part, he was endlessly patient, and he understood the crises that actors have with their lines. He had very clear ideas about how he wanted things to look, and his confidence conveyed itself to his actors and often gave them an acting ability they’d barely dreamed of. In addition, he produced a stunning series of leading ladies. He would want to record the pioneering work of [Radleians] Sally Fielding and Nicola and Lucy Hudson’ (Hamish Aird).

With Drama firmly a part of the taught curriculum in the 2020s, the Drama Department was faced with the problem of the Covid-19 lockdown and how to teach throughout Virtual Radley. Rehearsals and casting for the school plays had to take place online for much of 2020, only bringing the project together on stage in the last few weeks of rehearsals.