20 minute read

DELEGATION AND RESPONSIBILITY

DELEGATION AND ACCOUNTABILITY, MAKING DECISIONS USING ENGINEERING JUDGEMENT

WHEN SOMETHING HAPPENS ON THE RAILWAY, WHO IS ACCOUNTABLE? AND WHO CAN STOP WORK OR TRAINS UNTIL IT'S SAFE TO RUN?

Colin Wheeler, in This ensured a personal focus on his regular safety safety. column for RailStaff, The responsibility chain was clearly remembers the time defined in the out-based districts when the engineer in and divisions. I was impressed by the charge really WAS in understanding of track patrollers and charge and questions whether the supervisors that, if they found an unsafe same philosophy applies today. section of railway, it was their immediate

There were occasions when I found it duty to report it and, if

Working as a railway engineer, I was stop trains running. part of organisations which would now Finding a derailment level of be viewed as autocratic. During years track twist, embankment giving with British Rail, I worked out of offices in way, broken rail, flooded tracks Leeds, York, Sheffield, London, Newcastle or a bridge damaged by a large upon Tyne, Manchester and Liverpool. road vehicle rendering it unsafe I recall management meetings at which to use are relevant examples. I was either present at, told about or The decision to close the chaired. There was no question of voting railway or to impose an axle followed by a majority decision leading weight or speed restriction to corporate responsibility. The engineer could only be lifted by someone was personally responsible for the both qualified and senior, who railway infrastructure and could be held then themselves became accountable. personally responsible.

warranted, tell the signaller to necessary to overrule the management “Lack of engagement” team. I recall the railway’s solicitors In the July/August edition of informing me that, if things went wrong, Railstaff, I reported details of legal assistance would be provided, but, the accident investigation by if found guilty of getting it wrong, I could RAIB (Rail Accident Investigation expect to lose both my job and my pension! Branch) of the eight-coach HST Colin Wheeler.

passenger train at Corby in Northamptonshire that ran into material that had been washed onto the tracks and subsequently became trapped when more wash out material came down behind it.

The investigation included the examination of records of meetings with the local council and Environment Agency dating back as far as the 1960s. In turn, this led to the identification of a “lack of engagement between the various parties responsible for the flood management system”.

I suggest the failure was due to no single, identified individual with engineering knowledge being responsible and accountable for all aspects of line safety.

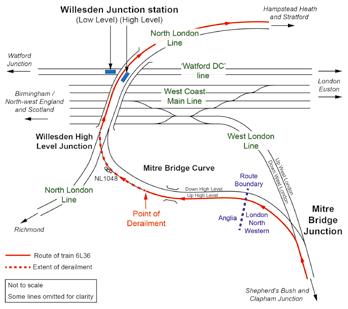

On 25 August, RAIB released its report (07/2020) into a freight train derailment at Willesden High Level Junction that happened on 6 May last year. At around 21:30; a single wagon in the train derailed on the curve, but re-railed itself as it passed over the junction!

RAIB notes that “such a derailment has the potential to foul lines that are open to passenger traffic”.

The earth embankment had been monitored by Network Rail since October 2016. It was showing “signs of progressive seasonal movement”. The empty two-axle wagon derailed “where cross level had been changing”, having encountered a significant track twist (later measured as 1 in 120 over 3 metres).

The wagon had an uneven load distribution, and a “diagonal wheel load imbalance which had not been detected by routine maintenance”. Its left-hand wheel flange climbed over the rail head. A check rail would have prevented this, but Network Rail’s risk assessment concluded that this safeguard was not necessary on the small radius curve.

The 21-wagon train was stopped at signal NL 1048. As it pulled away, it reached a speed of 8mph before it derailed. Signallers saw what they took to be an axle counter failure after the train had passed, so brought it to a halt at Hampstead Heath. The driver was asked to check that the train had not divided. When that had been done, he was given permission to continue. Around 14:00 hours the following day, signalling technicians attending lineside equipment discovered the track damage and severed cables.

One of RAIB’s recommendations deals with two-axle wagon maintenance and is directed at DB Cargo. Network Rail is the recipient of the other recommendations which include “the use and limitations of track geometry measurement trains, track condition and problems with the track bed and supporting earthwork structures.”

Under ‘additional learning points’, RAIB’s report refers to indicators of poor track bed condition and the importance of good liaison between track and earthworks as well as the management of wagon diagonal wheel imbalance.

In 2016, a supervisor’s report noted that “vertical alignment of track looked to be poor and a nearby OLE mast was leaning”. This was reported to the earthwork’s management team. On 11 July 2018, a section manager inspected and noted that the ballast ordered in 2016 “had yet to be delivered”!

Embankment examinations were carried out on a five-year cycle. On 10 June 2016, after the upside slope had been de-vegetated, it was inspected and awarded an increased earthwork hazard rating of Category C – ‘average’.

Specialist engineering consultants visited site on 15 March 2019. Their 1 May 2019 report gave “several design options” but was awaiting a decision at the time of the accident.

RAIB found a lack of structured liaison between the earthwork management and track teams. It was rare for the earthwork management team to notify the track team of a problem or requirement. Usually others alerted them!

The report does not identify the responsible engineer, who should have had all available facts and taken engineering responsibility, arguably at a date nearer to 2016.

Diesel oil freight train burns for 33 hours at Welsh SSSI

At just before 23:20 on Wednesday 26 August, a freight train derailed at Morlais Junction, Llangennech, near Llanelli. The tanker train 6A11 consisted of 25 wagons, each containing up to 75.5 tonnes of diesel or gas oil. It formed the 21:52 service from Robestson to Theale. Ten wagons, positions 3 to 12, derailed on the Up District line, but just three of them burnt and/or leaked into the nearby Loughhor Estuary. The total spillage was 330,000 litres.

It took the fire brigade around 33 hours to extinguish the blaze. Fourteen pumps were used and the accident was classified as a major incident and Category 1 Environmental Incident. The site is both a Special Area of Conservation and a Site of Special Scientific Interest.

An 800-metre evacuation zone was put in place and around 300 people were temporarily accommodated in Llangennech Community Centre or Bryn School until they were allowed back to their homes at 05:30 the following morning. The initial report of the derailment came from the train driver, who was unhurt and had detached the locomotive and moved it some 400 metres away after seeing the fire start. RAIB’s investigation is underway.

On 21 September, RAIB issued an update. The preliminary examination has established that, during the journey from Robeston, the brakes on all the wheels of the third wagon were applied and remained so until the derailment. Three axles continued to turn, albeit with their brakes dragging, but the leading axle stopped rotating. Consequently a 230mm-long wheel flat spot developed, together with a substantial ‘false flange’.

When the train reached Morlais Junction, the false flange (a raised lip on the outer side of the wheel flange) caught the converging stock rail and was derailed. The locomotive and first two wagons went to the right but wagon 3 went straight on and turned over. Much of the track was destroyed and a further nine wagons derailed as a result.

RAIB’s update says their investigation will include the third wagon brakes, how the fuel was spilt and the maintenance history of the third wagon. Near miss Deansgate-Castlefield Manchester Metrolink

RAIB’s report 06/2020 was published on 3 August and relates to a signal passed at danger by a Metrolink tram on 17 May 2019. The tram arriving at the central tram stop platform at Deansgate/Castlefield but failed to make its scheduled stop. It travelled through the platform at 9mph and passed a stop signal into the path of an oncoming second tram approaching the junction as part of a signalled movement.

The driver of the second tram saw the first tram approaching and stopped in time to avoid a collision.

RAIB concluded that the driver of the first tram failed to stop due to “a temporary loss of awareness”. It decided that this was “a result of a medical event or the driver losing focus on the driving task”.

The driver had been involved in previous incidents but the tramway operator, Keolis Amey Metrolink, had not adequately addressed his performance. RAIB found that the driver’s safety device on the tram did not detect or mitigate the driver’s loss of awareness because it was not designed to do so!

RAIB’s first recommendation is for Keolis Amey Metrolink, to review and update its strategy for managing the risk of trams passing signals at danger. Two other recommendations require them to “ensure medical fitness requirements for drivers are based on an understanding of the risks of their activities and that its fatigue management system meets with relevant industry guidance and best practice”.

Carmont/Stonehaven passenger train accident

At 09:38 on the morning of 12 August, all six vehicles of a passenger train derailed after the train ran into a landslip. Three individuals including the train driver and conductor lost their lives. There were just nine people in total on the train.

Between 05:00 and 09:00 that morning, over two inches of rain had fallen; the August average is for less than three inches in the whole month. The HST (High Speed Train) set had left Aberdeen on time at 06:38, travelling southwards on the Up line, and was on time when stopped by the signaller at Carmont.

The signaller received a report from the driver of a northbound train on the Down line that a landslip was obstructing the Up line between Carmont and Lawrencekirk. The northbound train stopped at Stonehaven and its passengers disembarked. It was decided that, as the southbound train could not continue, it would return north to Stonehaven (See Map).

Permission was given for it to use Carmont crossover. After crossing over, its speed increased to 72.8mph before it ran into a Down line bank slip and derailed. It then travelled on for 77 yards before running into a bridge parapet. The leading power car fell down a wooded embankment as did the third carriage. The first passenger carriage rotated across the track and ended up on its roof whilst the fourth carriage remained upright. The rear power car derailed but also remained upright. RAIB’s investigation is underway.

Worlingham near miss

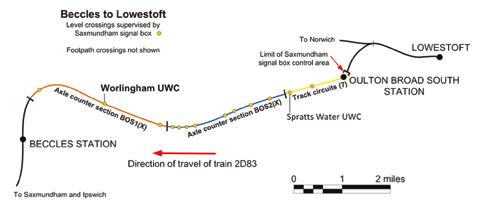

RAIB’s Safety Digest concerning a near miss at Worlingham user-worked crossing (UWC) was published on 27 August. Its messages stress the importance of reducing the risks from signaller errors at UWCs, in particular those controlled from Saxmundham signal box, ensuring signallers are briefed when changes are made and that they do not rely on a perception of lapsed time when making safety critical decisions due to the potential for them to be distracted.

At 13:18 on 8 June, the driver of the 13:07 Lowestoft to Ipswich passenger train applied the emergency brake on seeing a vehicle towing a trailer on Worlingham UWC. The

train was 350 metres from the crossing and travelling at 55mph – just 14 seconds running time away. The Saxmundham signaller had given permission on the understanding that the vehicles would take less than two minutes to cross. The call ended 77 seconds before the train would have reached the crossing had its driver not applied the emergency brake.

Back in 30 March 2017, the Office of Rail and Road (ORR) served an Improvement Notice on Network Rail, identifying signal boxes on the Anglia Route where “signallers have no means of consistently and reliably determining train movements in the area of a UWC before authorising a person to cross”. The notice required Network Rail to carry out a risk assessment and identify measures to control the risk.

On 23 January 2018, ORR issued a second Improvement Notice, with a compliance date of 31 March 2021, requiring Network Rail to implement preventative protection measures identified in a schedule. These included axle

counters to enable the positions of trains to be determined more precisely.

In May, Network Rail introduced additional axle counters subdividing the long sections controlled by Saxmundham Box. Signallers were briefed that this was to provide “more confidence when telling level crossing users if it was safe to cross”. As may be seen on the diagram, signal section BOS(X) was divided into BOS1(X) and BOS2(X).

When these axle counter sections were established, signallers were provided with a table indicating that permission should not be given for Worlingham crossing after a train approaching from Oulton Broad South had occupied BOS2(X). The signaller’s display does not give additional information about the location of the train. The train occupied BOS2(X) 130 seconds before the driver of the road vehicle requested permission to cross.

The signaller involved on 8 June had not been trained in the use of the additional information provided by the display and table.

In the ten minutes before taking the call from the vehicle driver waiting to cross, the signaller had taken six calls from other UWCs, two of which were after the train had left Oulton Broad Station. When giving permission to cross, the signaller did not realise how much time had elapsed since the train left the station.

When the axle counters were added into the Saxmundham scheme, no assessment of signaller workload was made. It was decided that the call volumes and signalling workload would not be altered. I suggest the signallers were unconvinced of the value of the additional information made available.

The authority to stop trains

Even dedicated and competent railway engineers, operators, supervisors and trained staff will make mistakes. Involving those with superior knowledge to coordinate and become personally responsible is a key requirement. For rail infrastructure and rolling stock, I suggest this is best achieved by using qualified people who can be held personally and professionally responsible for their decisions. This would surely result in a coordination of accountable professional management.

Responsible railway individuals carrying these responsibilities need the authority to stop trains running unless satisfied that the infrastructure, rolling stock and operating conditions are safe and suitable.

This is Dave Condential Reporting for Safety

Dave works trackside and is concerned about his PPE Dave spoke up but was told to make do Dave called CIRAS and now has new gloves Dave is smart Be like Dave

The name we’ve used is fictional. We share your concern so the company can address it. You will not be identified.

Work environment

Rules & procedures Fatigue Welfare facilities Equipment

www.ciras.org.uk

Shift design Safety practices Training & competence

A COMEDY OF ERRORS

AN INCIDENT AT ROCHFORD, ESSEX, SHOWED THAT, FAR FROM THERE BEING A SAFE SYSTEM OF WORK, IT WASN'T SAFE AND THERE WAS NO SYSTEM

The Rail Accident Investigation Board (RAIB) report into an incident at Rochford in Essex on 25 January 2020 describes a dreadful site situation followed by an equally inadequate response from on call staff.

RAIB chief inspector Simon French has drawn attention to this report and the potential for fatalities, adding “the investigation found a introduced its on-track plant operations scheme,

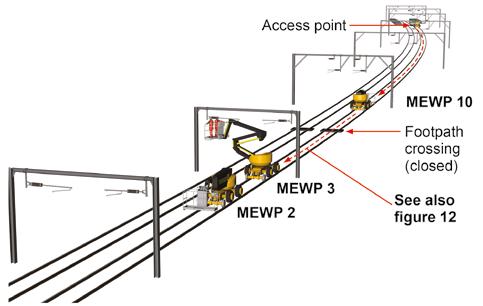

Whilst MEWP 10 travelled at 7mph (walking pace is stipulated) to MEWP 2, its supervisor stayed at its site of work. It was intended that the MEWPs would work in pairs back-to-back, catalogue of errors and omissions, duplicated

3 if they had spare ones. Without involving lines of control, and a lack of clarity about who was in charge”.

He highlights the current need for Network Rail to find a more effective way of managing the movements of multiple vehicles within a work site.

OPERATOR NEEDED HELP!

Work on the electrified overhead line, during a scheduled possession beginning at 02:15, involved using a wiring train and seven MEWPs (Mobile Elevated Work Platforms) to remove wiring on the Up line.

The possession was delayed by the wiring train and not taken until 03:28. Six of the MEWPs were on-tracked and travelled to various work sites. MEWP 10 was not on-tracked until 09:30. Its operator was working his first shift after several months and needed the assistance of a supervisor to on-track the machine and carry out the necessary brake test. Individual machine supervisors were provided for each MEWP, together with a POS (Plant Operations Scheme representative).

Between January and June 2014, 134 accidents and incidents involving on-track plant were reported. for which companies are required to provide representatives on site.

A fault developed on MEWP 2, needing a fitter who was taken to the machine from the access point by MEWP 10 (see diagram).

with each machine supervised by a machine controller and each pair of machines managed by a site supervisor.

At 10:50, the operator of MEWP 10 discovered that the required slings were not in the machine basket, so the operator and linesman began to search and asked the staff of MEWPs 2 and Subsequently, Network Rail

the machine supervisor, MEWP 10 then set off towards MEWPs 2 and 3, leaving the supervisor shouting and running after it – he was unable to keep up as it reached 10 mph.

A fitter working on a platform sensor fault on MEWP 2 saw MEWP 10 approaching and shouted a warning to colleagues on and around MEWP 3. MEWP 3’s machine supervisor realised that a collision was inevitable when MEWP 10 was just 15-20 metres away.

MEWP 3’s headphone-wearing operator and linesman did not hear the warning and the impact threw them against the basket framework. Both were wearing safety harnesses and only sustained minor injuries, for which they received hospital treatment.

ES WAS IN A SUPERMARKET!

The PIC (Person in Charge) was contacted at 11:10 but was managing two other MEWPs near Southend station, so the site supervisor was asked to manage the situation – the POS representative was not involved. The site supervisor for MEWPs 2 and 3 contacted the ES (Engineering Supervisor), who was in the local supermarket but “did not know what he needed to do and had no training in managing the situation or competence in accident investigation”.

Both the PICOP (Person in Charge of Possession) and Romford operations centre were contacted, and the Anglia Route Operations OnCall manager was asked to attend site and collect evidence. The On-Call Anglia Route Maintenance manager was asked to attend in support.

Half an hour passed with no response from either of them, so Route Control contacted the MOM (Mobile Operations Manager), advising that drugs and alcohol testing had been arranged. The On-Call Maintenance Manager arrived on site at 2:16 pm but waited for the On-Call Operations Manager.

Neither On-Call manager arrived with PPE and one advised that they had been attending a social event.

RAIB contacted the Operations Manager confirming the types of evidence to gather, but this was not done.

MULTIPLE CAUSES

The comprehensive RAIB report lists the causes:

The MEWP operator drove at more than walking pace (actually reaching 10mph) and lost awareness when driving towards a stationary MEWP;

The Machine Controller was unable to effectively supervise MEWP 10;

Site organisation was not conducive to safe management of supervisory roles on site, there was a lack of clarity about roles and responsibilities leading to confusion among staff

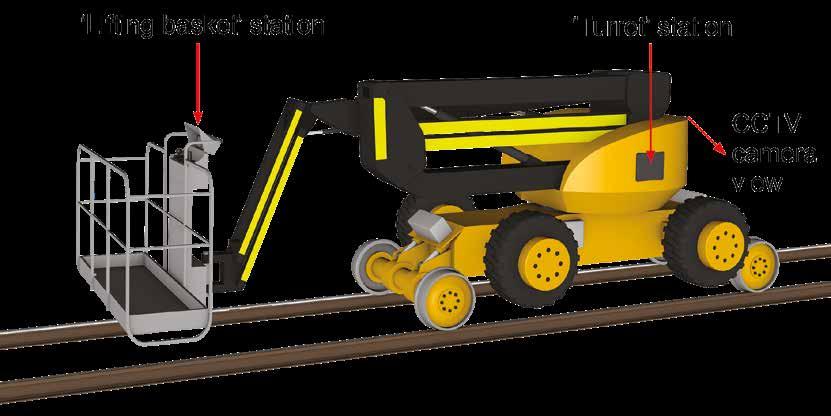

(Above) The Skyrailer 440 machine. (Below) Skyrailer MEWP 10 involved in the accident.

about who was in charge of the safe movement of on-track plant;

Network Rail’s Overhead Condition Renewals Organisation (OCR) valued “getting the job done over rule-compliance and safety”;

A culture of disrespect existed towards contractors undertaking the role of machine controller within OCR worksites;

Network Rail had been unaware of the poor working relationships and culture and the extent of non-compliance on OCR sites, and its management assurance process had not identified these issues;

Network Rail’s incident management and on-site investigation were inadequate and resulted in a lack of co-ordination and loss of evidence.

PERSONAL ACCOUNTABILITY AND RESPONSIBILITY

During my time working from British Rail’s divisional offices, I recall being On-Call for almost 20 years. Bleepers were replaced by huge brick mobile telephones and we all carried details of procedures and contacts specifying actions and contacts if accidents and incidents occurred. I kept a separate folder for dealing with injury accidents and fatalities. Failure to attend and take action when called out was unthinkable.

The RAIB report identifies a lack of team spirit, excessive supervisory roles that were neither understood nor, apparently, of use, cultural site conflicts and on-call individuals who were neither mentally or physically equipped to respond when called out to an accident.

This report describes such a dreadful state of affairs that I sought the opinion of the Office of Rail and Road (ORR). I spoke with Anna O’Connor, principal inspector of railways and also ORR’s head of projects for its Network Rail division. We agreed that the report was far reaching and that its recommendations were to be welcomed. Also, that the duplication of supervisor roles looked to be the result of successive additions and updating by safety professionals.

Overall, we both agreed that the circumstances that resulted in the accident were simply awful!

Anna confirmed that there was a lack of team spirit at Rochford and probably other overhead condition renewals (OCR) sites, exacerbated by the hazardous excess of supervisory roles. She also agreed that the failure of the on-call management team was unacceptable in timescale and in dealing with the accident.

I commented that, when I undertook call-out duties as a railway civil engineer, I was judged by my speed of response and the actions I took on arriving on site. When on-call, attendance at any social event was necessarily off the agenda.

When I asked about the reported “cultural conflicts”, she confirmed that this was the case and that a degree of racism was also evident and systemic. The mixture of staff on site, from a range of different employers did nothing to foster a spirit of trust and cooperation.

IMPORTANT RECOMMENDATIONS

Having discussed the poor safety culture that exists within current OCR organisations and the importance of suitable on-call staff, Anna expressed her support for the RAIB’s recommendations, particularly the first two listed in the report.

The first directs Network Rail to “reduce the confusion among staff responsible for operating and controlling the movement of on track plant, leading to the adoption of unofficial systems of work”. Simplifying plant movement rules and reducing supervision, as well as harmonising or changing the circumstances that are in the way of committed team working, including using a number of different organisations, needs to be addressed.

I advocate forming teams that stay together over long periods of working. This will, if well managed, be safer and more productive.

The second recommendation identifies the need to improve the management of the Sentinel system, including the way in which trainers assess English language skills, which we agreed are especially important for those undertaking safety-critical work.

Anna O’Connor commented that she has personal experience of inadequate training in Personal Track Safety from biannual renewal course attendances. I recommended the introduction of “mystery shoppers” to assess training organisations. Having undertaken the role occasionally years ago, I recall it as being easy to perform and effective. Unannounced audits randomly selected would be effective and provide measurable information on the effectiveness of the training.

I would like to thank Anna O’Connor and ORR for discussing the findings of this report so frankly. Now we all have to make sure they are adopted as soon as possible.