16 minute read

Amtrak at 50, Part 1

AMTRAK AT 50 A HALFCENTURY AGO …

A rider and advocate remembers Amtrak’s early years.

BY DAVID PETER ALAN, CONTRIBUTING EDITOR

March 1993: The Swedish X2000 tilting high-speed trainset is seen operating on the Northeast Corridor in test Metroliner revenue service, on an evening New York to Washington, D.C., run. Amtrak evaluated the X2000 and the Siemens InterCityExpress prior to ordering the current fleet of Bombardier/Alstom Acela Express trainsets. In 2021, new Alstom trainsets will be introduced to Boston-New York-Washington, D.C., service. This photo was taken from the rear of an NJ Transit North Jersey Coast Line commuter train.

William C. Vantuono. All other photos courtesy of Amtrak As we prepare to observe Amtrak’s 50th anniversary, my memories of a half-century ago flood into consciousness: memories of the last days of most of the nation’s passenger trains and the magnitude of how many were doomed, memories of Amtrak’s early days and the routes and services that still ran at the beginning, and memories of deep uncertainty about the future of our trains.

My assignment, as part of our coverage, is to recall those memories. A few are the “Streamliner Memories” of which anti-rail activist Randall O’Toole is so fond. Most are about riding trains that were about to die, while hoping that the few survivors would live long and prosper.

Few seemed to believe that at the time, and many riders (mostly railfans, not the advocates we have today) understood that the purpose of the Rail Passenger Service Act of 1970 was to relieve the freight railroads of the responsibility and cost of running passenger trains. We also perceived that the actual, but unstated, result of the Act was to get rid of passenger trains more quickly than the “train-off” procedures of the old Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC; replaced by the Surface Transportation Board) would allow. At one stroke, we lost 65% of the nation’s long-distance trains (using the 750-mile standard from 2008) and 64% of the trains with shorter runs; both long-distance and medium-distance outside the Northeast Corridor (NEC). The NEC and its branches did much better; two-thirds of those trains survived. Few of us expected the remaining trains elsewhere to survive the 1970s.

I personally doubt that many riders would have expected Amtrak to last for ten years, much less 50. It seemed particularly and ironically inconceivable to think that, on its 50th anniversary, Amtrak would be running its lowest level of service in history, even (or especially) as a temporary low point brought on by a global pandemic.

No need to recap Amtrak’s history here. Amtrak itself presents a detailed timeline from 1970 through 2019 at https://history. amtrak.com/amtraks-history/historic-timeline. There is more on Amtrak’s history blog, history.amtrak.com, too. An introductory post from 2014 reported: “Amtrak was originally established by the Congressional Rail Passenger Service Act, which consolidated the U.S.’s existing 20 passenger railroads into one. That’s also back when we served 43 states with a total of 21 routes.”

Other commentators have recounted Amtrak’s early days, as well. According to Stephen C. Rogers at https://www. encyclopedia.com/history/encyclopediasalmanacs-transcripts-and-maps/rail-passenger-service-act-1970, “Congress enacted the Rail Passenger Service Act (RPSA) (P.L. 91-518, 84 Stat. 1327) in 1970 under the commerce clause of the U.S. Constitution to preserve intercity rail passenger service in the United States. The RPSA required Amtrak to provide passenger service between points within an integrated ‘basic system’ of routes designated by the U.S. Secretary of Transportation, with a view to eliminating the least necessary operations.”

The Act also established Amtrak as a “for profit” corporation—a source of trouble ever since, because no passenger railroad anywhere in the world that runs scheduled service makes a profit, in that sense. Still, it is doubtful that Amtrak would have seen the light of day without the fiction that it could turn a profit. Jeff Davis of the Eno Transportation Center

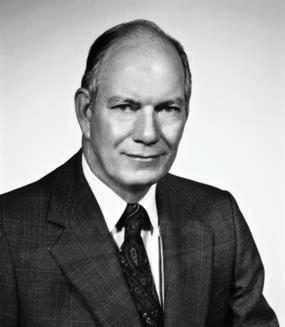

Alan S. Boyd (1922-2020) served as Amtrak President from 1978 to 1982. A lawyer by training, in 1967 Boyd became the first Secretary of the newly created USDOT. He had headed a task force that looked into establishing a cabinet-level department that would be home to a collection of transportationrelated agencies. Between his time with the federal government and Amtrak, Boyd led the Illinois Central Railroad.

W. Graham Claytor, Jr. (1912-1994) served as the fourth President of Amtrak from 1982 to 1993. He is widely regarded as the finest, most-accomplished President in Amtrak history. A lawyer and World War II naval hero, Claytor gained extensive knowledge of passenger and freight railroading as the Vice President, President and Chairman of Southern Railway between 1963 and 1977. Following retirement from Southern, Claytor began a second career in government service with the Carter Administration. Between 1977 and 1981, Claytor served as Secretary of the Navy, Acting Secretary of Transportation and Deputy Secretary of Defense. Under his leadership, Amtrak established a joint Labor/ Management Productivity Council; restarted the popular Auto Train (Lorton-Sanford); launched the toll free 1-800-USARAIL reservations number; surpassed Eastern Airlines to become the leading WashingtonNew York carrier; introduced a computerized “yield management” system to handle ticket sales; completed the West Side Connection in New York City; initiated Capitol Corridor service; received the first GE Genesis Series diesel-electric locomotives; evaluated European high-speed trainsets for Northeast Corridor service; and fought off attempts by the Reagan Administration to eliminate most of Amtrak’s federal funding. presents a detailed history of Amtrak’s formation, including when it was called Railpax, at https://www.enotrans.org/article/amtrakat-50-the-rail-passenger-service-act-of-1970/. The history took some amazing turns during the early days, including how Assistant to the President for Domestic Policy Daniel Patrick Moynihan (later U.S. Senator) and Transportation Secretary John Volpe eventually overcame resistance from President Richard Nixon and Assistant to the President for Domestic Affairs John Ehrlichman (later of Watergate fame). All four are long dead, while Amtrak lives on.

Few knew of the Nixon Administration’s resistance at the time. Many did know that the trains were dropping like proverbial flies. In 1970 alone, we lost the Lake Cities on the Erie-Lackawanna (Lackawanna from Hoboken to Binghamton and Erie the rest of the way to Chicago), the portion of the Missouri Pacific’s Texas Eagle that ran in Texas (Amtrak later revived it, but nobody could have foreseen that at the time), and the legendary California Zephyr, including the famous portion on the Western Pacific Railroad. The Act called for a six-month moratorium on train-offs before Amtrak began, but we knew that it was only a short reprieve. 1969 was worse than 1970, because trains were eliminated throughout the year. Many knew that most of the trains were doomed, but didn’t know exactly which ones.

Before Amtrak started, I had made a few specific trips: to visit Chicago in 1969, and to visit my grandmother in Florida, riding CSX predecessor Seaboard Coast Line. I also made two relatively long itineraries: in 1970, when I completed my B.S. degree, and in April 1971, after finishing my M.B.A. I had to plan the latter trip before the initial Amtrak route map was announced on March 22, so I was not sure which trains would soon die. I rode some that did: the Nancy Hanks II on the Central of Georgia between Savannah and Atlanta, the Pocahontas on the Norfolk & Western, and the Union Pacific’s City of Kansas City among them. I also rode some that survived but would change: Southern Railway’s Southerner (now the Amtrak Crescent), and Santa Fe trains with their famous Fred Harvey dining service. Some of them lasted for a while under Amtrak but eventually disappeared. Others went away but later returned.

Nothing changed at first, except there were fewer trains. The equipment was the same: streamlined cars in their railroad liveries, crews sporting their railroad uniforms, and the food that made dining cars famous, except that the Santa Fe had taken Fred Harvey’s name off the menu. Participating railroads even printed their own “Amtrak timetables” during 1971 and into 1972 for the trains they still operated.

Then came the homogenization. Equipment started appearing in places where it had never run before. An Amtrak consist would carry cars from several railroads. Railfans referred to that time as Amtrak’s “Rainbow Period” before everything was repainted in Amtrak livery. The dining service was standardized in 1973, and regional food specialties mostly became a thing of the past.

Ironically and amazingly, the size of Amtrak’s National Network is the same today as it was in the original plan: 14 trains, not counting the Auto-Train, which Amtrak took over from the previously independent Auto-Train Corp. in 1981, and on which passengers without automobiles are not allowed to ride. Except for a few re-routings on short segments and the replacement of the Lone Star Limited (Chicago-Houston on the Santa Fe, which came off in 1979) with the Texas Eagle (Chicago-San Antonio, mostly on the historic Missouri Pacific, now part of UP), which came back in 1974 as the Inter-American to Laredo and resumed its historic name in 1981, today’s long-distance network west of Chicago and New Orleans is unchanged from the 1971 route structure.

There have been some changes east of Chicago. A full-service train, the Champion between New York and St. Petersburg, Fla., is gone; replaced by the Palmetto, a coach train that does not run south of Savannah. The Broadway Limited ran between New York and Chicago through Pennsylvania until 1995. The Lake Shore Limited ran between the same endpoints, but through Upstate New York, and was omitted from the original network. It came back on June 11, 1971 for 207 days under an interstate funding agreement that did not work (I rode to Cleveland on the last run), and returned permanently in 1975. The National Limited between New York and St. Louis (through-running to Kansas City) and the Chicago-Florida Floridian were also discontinued in 1979. They were succeeded by the Capitol Limited in 1981 (the last long-distance train added and still operating) and Amtrak’s takeover

Amtrak officials inspect some of the first concrete ties installed by the new Track Laying Machine at Shannock, R.I., as part of the Northeast Corridor Improvement Project. The track inspectors emerged from the Budd RDC in the background. Passenger service representative Patty Saunders, circa 1972.

of the New Orleans train (now the Crescent) from the Southern Railway in 1979.

Congress has frozen today’s long-distance network in time. Section 201(a)(5)(C) of the Passenger Rail Investment & Improvement Act of 2009 (PRIIA; this provision now codified as 49 U.S.C. 24102((7)(C)) defines Amtrak’s National Network as the trains whose routes were at least 750 miles long and which were operating then, so there is no provision for any expansion beyond the original 1971 level. There is one exception: Gulf Coast service east of New Orleans, which ran from 1993 until Hurricane Katrina struck in 2005. Railway Age has reported the current effort to restore service to Mobile, which could happen as soon as next year, but service all the way east to Florida still appears unlikely.

Amtrak based its original route structure on endpoints, and was criticized for ignoring intermediate stops, even if all of them were different. When the Lake Shore Limited did not run, Empire Service in New York State hit a dead-end at Buffalo, except for a connection to a separate train on the Toronto, Hamilton & Buffalo (TH&B) and Canadian Pacific (CP) route to Toronto. It was the only train between the two countries at the time. Between Chicago and the Northwest, Amtrak chose the Empire Builder route on Burlington Northern, mostly on the historic Great Northern portion, over the more-southerly North Coast Limited route on the historic Northern Pacific route. The latter came back in 1972 as the tri-weekly and inaptly-named North Coast Hiawatha, which was also discontinued in 1979. There have been several unsuccessful efforts to restore service on part of that route over the past 30 to 40 years, and another has recently begun in Montana.

Not every railroad joined Amtrak. The Santa Fe considered continuing to run its trains, which were still popular, but joined Amtrak at the last minute. Other railroads kept operating trains under their own flags. The Georgia Railroad ran a mixed train between Atlanta and Augusta. The day I rode, it had one dirty coach that had seen service on the Crescent in better times. The Rock Island ran its Quad Cities Rocket and Peoria Rocket between Chicago and those destinations, complete with a dining car. I bought a ticket to Morris, had a quick dinner, got off at Joliet, and returned to Chicago on a commuter train. The Southern kept running a train between Washington, D.C., and Lynchburg (a remnant of the Birmingham Special), a portion of the Piedmont Limited going only as far south as Atlanta on an all-day schedule, and a tri-weekly connecting train between Salisbury and Asheville, N.C. All of those trains ran post-Amtrak for only about five years. The Southern turned the New Orleans train over to Amtrak in 1979, and it became part of the Amtrak network as originally planned.

The most famous holdout was the Denver & Rio Grande, which continued to run its portion of the then-defunct California Zephyr between Denver and Salt Lake City as the Rio Grande Zephyr. It ran on a triweekly schedule that did not connect on the same day with Amtrak’s Zephyr to and from Chicago, so my first visit to Denver lasted 22 hours. The consist was magnificent, with domes on four of its eight cars, and a dining car that featured the railroad’s famous Rocky Mountain Trout for dinner. During that period, Amtrak ran its own San Francisco Zephyr on the Union Pacific’s Overland Route through Wyoming, which continued as part of the Pioneer until 1997. The D&RG’s independent train lasted until 1983, at which time Amtrak moved its train onto the Moffat Tunnel route, as was planned in 1971.

So how are Amtrak’s routes doing today? In a nutshell, there are fewer trains than ever on most of them. Some trains have not run at all for the past year, as the COVID-19 virus has shut down many services, including public transportation.

Amtrak’s greatest growth has occurred on its corridors; both the NEC and its branches, and state-supported routes elsewhere. Perhaps Amtrak’s greatest irony occurred there, too, because service on most of them has declined so sharply since the virus struck that service has fallen far below 1971 levels. There are only 30

Amfleet cars came in five configurations, including the long-distance Amcoach in this 1981 photo. Long-distance Amcoaches had 60 seats in a 2x2 configuration vs. coaches with 84 seats used on short-distance corridor services.

weekday trains (fewer on weekends) on the NEC and its branches today, compared with 73 in 1971. There were 19 trains on other corridors then (including Empire Service), and there are 23 on those lines today. There are 25 trains running on corridors established later, mostly in California.

Things are beginning to look up. The 12 Amtrak long-distance trains that were reduced to tri-weekly operation in October 2020 are returning to daily service in late May or early June. That is a huge step in the right direction.

Amtrak is also pushing hard for a new start, the first in two decades. Maybe it’s because Sen. Roger Wicker (R-Miss.) and Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg want it, but Amtrak plans to initiate service between New Orleans and Mobile as soon as next year. It would be the first new route since the Downeaster between Boston and Portland, Maine, started in 2001. If the line returns as planned, that in itself could be a harbinger of better times to come.

Looking at a hypothetical alternative, though, we don’t know how long the trains would have lasted if the freight railroads had kept running them into the 1970s and maybe beyond. Only the Rio Grande Zephyr made it past that decade by three years. If all trains that were still on the rails in 1971 went through the ICC train-off process, how many would still be running today? Maybe a few, but probably none.

With its statutory mandate for profitability that knowledgeable people knew was fiction, the talk at the time was that Amtrak was designed to accelerate the demise of passenger trains and kill them off during the decade. Amtrak eliminated six trains in 1979, during the Jimmy Carter Administration, but the riding public had other ideas. There weren’t many trains left, but people kept riding them. They continue to object to losing their trains, and Amtrak’s flirtations with tri-weekly long-distance networks in the mid-1990s were reversed by public demand, or perhaps by the sort of political action that results from it.

It is less enjoyable to ride Amtrak than it used to be, but at least we still have some trains—a skeletal network with only a few routes. The alternative would probably be no trains at all, except possibly corridors in the Northeast, California, and maybe Chicagoland. The fact remains that the network could grow someday, if circumstances change to support such growth. Amtrak hasn’t yet achieved many advocates’ and riders’ hopes that it would grow into a major national passenger rail network with numerous routes and corridors operating frequent service. But that’s better than no trains at all, which could be the situation today if it weren’t for Amtrak.

Happy 50th Birthday, Amtrak!

Paul Reistrup served as Amtrak President from 1975 to 1978. He came to the company following extensive experience in passenger rail services with the Baltimore & Ohio and Illinois Central. Under Reistrup, Amtrak purchased the Beech Grove, Ind., heavy maintenance facility from Penn Central; introduced new Amfleet and Superliner cars into revenue service; and gained control of most of the Boston-Washington, D.C., Northeast Corridor.

A controversial figure, George Warrington (1952-2007) served as Amtrak President from 1998 to 2002. He had worked for the New Jersey DOT and New Jersey Transit, served as Executive Director of the Delaware River Port Authority, and oversaw Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor business unit prior to becoming President. Under Warrington, Amtrak completed Northeast Corridor electrification between New Haven and Boston and launched the high-speed Acela Express. In 2002, he returned to NJT as Executive Director.