VOLUME 11 Y/2023

13 07

LETTER FROM THE EDITORS

CONTRIBUTORS

FEMININE DOMAIN

Julia Mobbs

MENOPAUSE DOESN’T KILL A WOMAN

Julia Mobbs

QUIET BUT NOT SILENT

Zoey Yang

(UNTITLED) LABOURERS

Aimée Lebeau

MOUNTAIN GIRL

Maral Matig

ARCHIVING THE CLUB

Billy Houde

ALEJANDRA

Nesreen Galal

01

TABLE OF CONTENTS

05 07 09 11

19

17

Y/2023

Rianna Gurevitch 39

BE DARING, DARLING

TENNIS SKIRT

Hannah Berger

KINDA FOCUSED ON BEING ADORABLE RIGHT NOW

Havana Xeros

CE QU’ILS NE PEUVENT NOUS PRENDRE...

Emma Morselli

AQUI ESTAMOS (HERE WE ARE)

Arantxa Martinez Dugas

I AM SAFE INSIDE THIS BODY

Spencer Allder REVIVAL

RAW Julie Glicenstajn

VOLUME 11 41 45 49 51 55 57 59 YIARA MAGAZINE

Andrea Chenier

Cher lecteur,

Merci d’avoir choisi Yiara Volume 11. Nous sommes extrêmement reconnaissantes d’avoir rencontré un tel enthousiasme de la part de la communauté artistique montréalaise et d’ailleurs, et c’est entièrement grâce à vous que Yiara a pu atteindre son onzième volume. Lorsque nous avons commencé ce projet, nous avons pris une publication avec une vie qui lui ait propre, et nous espérons lui avoir rendu justice. Yiara est un magazine, mais plus que cela, c’est est une mission. Nous avons été initialement fondée comme une publication avec le but de commencer une dialogue féministe intersectionnel. Dans les années qui ont suivi, nous sommes passés d’une focalisation sur les interventions féministes dans le discours de l’histoire de l’art à une orientation primaire sur les questions d’art et de féminisme, dans ses termes les plus généraux.

Dans notre onzième volume, nous nous concentrons sur les histoires individuelles et la narration, et nous cherchons à offrir diverses perspectives tout au long du travail que nous avons sélectionné pour l’impression. A qui Estamos commémore les victimes de féminicides et les efforts de leurs familles pour rechercher la vérité au Mexique et au-delà. La délicieuse série Alejandra est une insertion du regard féminin dans le genre noir, centré autour d’une femme fatale latina. raw reconstruit ce que la beauté féminine pourrait signifier après une chirurgie invasive. Archiving the Club attire notre attention sur les questions de censure en étudiant les romans graphiques de Sylvie Rancourt, une danseuse nue québécoise. i am safe inside this body et Revival invitent une consolidation holistique de soi à travers un amour-propre radical. Nous espérons que ces œuvres éduquent et inspirent, mais plus que tout, nous espérons qu’elles vous feront ressentir. Notre seul conseil est de laisser vos émotions parcourir ces pagesau fur et à mesure que vous les parcourez.

Il est impossible d’énumérer notre gratitude pour tous ceux qui ont rendu le onzième volume possible, mais quand même, nous essayons. Nous tenons à remercier toutes les personnes de Concordia qui ont contribué au soutien institutionnel et financier de notre mission, ainsi que tous les groupes communautaires avec lesquels nous avons eu le privilège de travailler. Yiara est générationnelle, et nous apprécions nos prédécesseurs Yiara. Nous apprécions la passion dévouée des membres de notre équipe et nous les remercions pour leur travail acharné et leur soutien indéfectible tout au long de l’année, sans lesquels nos opérations n’auraient pas été possibles. Enfin, nous vous remercions, chère.er lecteur.rice. En récupérant un exemplaire de Yiara Volume 11, vous nous avez donné une raison.

Sincèrement, Julia Bifulco and Margrethe Nielsen Co-rédactrices-en-chef

LETTRE DES RÉDACTRICES 01 Y/2023

Thank you for picking up a copy of Yiara Volume 11. We are utterly grateful to be met with such enthusiasm from the Montreal art community and beyond, and it is entirely due to you that Yiara has been able to reach its eleventh volume. When we inherited this project, we took on a true beating heart—a publication with a life of its own—and we hope to have done it justice. Yiara is a magazine, but more accurately, Yiara is a mission. We were initially founded as a publication that aimed to highlight and spark intersectional feminist dialogue. In the years since, we have expanded from a focus on feminist interventions in art-historical discourse to a primary orientation in the matters of art and feminism, in its broadest terms.

In our eleventh volume, we are focused on positionality and storytelling, and we seek to provide diverse perspectives throughout the work we have selected for print. A qui Estamos memorializes victims of femicide and the efforts of their families to seek the truth in Mexico and beyond. The delightfully campy Alejandra series is an insertion of the female gaze into the noir genre focused around a Latina femme fatale. raw reconstructs what feminine beauty might mean after an invasive surgery. Archiving the Club brings attention to censorship issues by studying the graphic novels of Sylvie Rancourt, a Québécoise nude dancer. Both i am safe inside this body and Revival invites a holistic consolidation of self through radical self-love. We hope that these works educate and inspire, but more than anything, we hope that they make you feel. Our only advice is to let your emotions navigate these pages for you as you travel through them.

It is impossible to enumerate our gratitude for all who made Volume 11 possible, but nonetheless, we will try. We wish to thank everyone at Concordia who has contributed institutional and financial support for our mission as well as to all community groups who we have had the privilege of working with. Yiara is generational, and we are so grateful for our Yiara predecessors who have laid the groundwork for us. We are appreciative for the devoted passion of our team members, and we thank them for their hard work and unwavering support throughout the year, without which our operations would not have been possible. Finally, we thank you, dear reader. By picking up a copy of Yiara Volume 11 you have given us reason to continue.

Sincerely,

Julia Bifulco and Margrethe Nielsen Co-Editors-in-Chief

LETTER FROM THE EDITORS YIARA MAGAZINE 02

Dear reader,

Nous aimerions commencer par reconnaître que l’Université Concordia est située en territoire autochtone, lequel n’a jamais été cédé. Nous reconnaissons la nation Kanien’kehá: ka comme gardienne des terres et des eaux sur lesquelles nous nous réunissons aujourd’hui. Tiohtià:ke / Montréal est historiquement connu comme un lieu de rassemblement pour de nombreuses Premières Nations, et aujourd’hui, une population autochtone diversifiée, ainsi que d’autres peuples, y résident. C’est dans le respect des liens avec le passé, le présent et l'avenir que nous reconnaissons les relations continues entre les Peuples Autochtones et autres personnes de la communauté montréalaise.

RECONAISSANCE DES TERRES 03 Y/2023

Concordia University is located on land which is the unceded traditional territory of the Kanien’kehá:ka. This land has also served as a gathering place for Abenaki, Anishinaabe, and other nations. As uninvited guests, it is our responsibility to honour the stewards of this land by educating ourselves on the histories and contemporary realities of First Peoples, and by contributing to the important work of reconciliation and decolonization. Furthermore, we respect the continued connections with the past, present, and future in our ongoing relationships with Indigenous and other peoples within the Montreal community.

Our mission of intersectional representation in art and art dialogues drive us, and as such, we work to highlight the achievements of artists belonging to marginalized and underrepresented backgrounds. We hope that Volume 11 reflects this pursuit, but we also acknowledge that there is much more work to be done.

LAND ACKNOWLEDGMENT YIARA MAGAZINE 04

Managing Editor

Yolanda Smith-Hanson

Events Coordinator

Maurane Dubois

Editors-in-Chief

Margrethe Nielsen

Julia Bifulco

Creative Director

Fernanda Alvarez Larrain

Marketing Director

Laila Meyer-Korrichi

Assistant Creative Director

Jane Eyre Jordans

Editors

Nadia Trudel

Clare Chasse

Agathe Leroy

Head Writer

Hashmita Alimchandani

Social Media Coordinator

Annabelle Donabedian

Artist Coordinator

Grace Lindquist

Kyra Pedro-Czako

Copy Editors

Alana Batten

Aélia Delêtre

Reina Ephrahim

Bianca Giglio

Contributors

Spencer Allder

Maze Laverty

Emma Morselli

Lune Wagner

MASTHEAD Y/2023

05

VOLUME 11 YIARA MAGAZINE 06

JULIA MOBBS is an artist presently based in Montreal pursuing a degree in Painting and Drawing at Concordia University. Mobbs works in a style that walks a line between abstraction and pure representation. The human form is a central motif in Mobbs’ work, and her works confer ideas of femininity, bodily existence, her lived environment, and their relationships to each other. This visual ambiguity mirrors Mobbs’s interest in exploring the ways in which women are forced to contend with ageing, and the relationship between women’s bodies and their social value.

FEATURE 07

FEMININE DOMAIN

Feminine Domain is an experimental charcoal drawing on raw canvas, highlighting Mobbs’ desire to blur the line between figuration and abstraction. The artist’s process for this work began by inputting excerpts from Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex into an AI image generator, and then using her non-dominant hand to create charcoal drawings of the generated images. The work is a preliminary exploration of the ideas that emerge from unrelenting representations of women’s bodies in mass media, but also questions around the derivations of visual culture. In Feminine Domain, Mobbs pushes these almost recognizable figures into the realm of the absurd. Of her approach, Mobbs shares, “We are surrounded by images of women. What do you do with that [as an artist]? How can I reinterpret these forms in my art? Making work is often political, so I want to be sure that I am intentional about what I’m making.”

08 VOLUME 11 YIARA MAGAZINE

MENOPAUSE DOESN’T KILL A WOMAN

Menopause Doesn’t Kill a Woman is a painting that presents a narrative scene of three women at different stages in their life: youth, middle, and old age. At the time of its production, Mobbs had been reading Simone de Beauvoir’s The Woman Destroyed, which ultimately inspired this painting. The book is a collection of three novellas outlining the experience of threewomen facing different crises: ageing, loneliness,

and falling out of love. Mobbs was curious about whether these crises were still relevant to wom en today, and whether they were issues specific to women. Beauvoir’s work reflects various existential anxieties that have been persistent in the lives of women—chief of which is the question of ageing and its correlated loss of social value. Through conversations with her mother and her own reflections, Mobbs worked through these complex ideas in her painting. The three figures are painted with their backs to the viewer, subtly and quietly refusing the various imposing gazes that are often thrust upon the bodies of women. However, this defiance is not overt nor is it necessarily repellant; the figures are represented with generosity, and thus the women in this painting are allowed to simply exist in their bodies and their environment in peace.

FEATURE 09

10 YIARA MAGAZINE

QUIET BUT NOT SILENT

Zoey Yang began drawing and playing piano at the age of two, and both art forms remain a strong passion of hers to this day. Yang feels that her visual art often takes on musical shapes, echoing the expressive forms found in abstract expressionism—a source of inspiration for the artist. She is originally from Beijing, China, has spent time living in the United Kingdom, and now resides in Montreal, Canada. She currently studies Cognitive Science at McGill University with a minor in Art History.

Quiet but not Silent depicts a serene nude model resting on a chair. Yang has a deep interest in colour theory—the psychological link between colours and emotions—a sentiment that is clear in this painting. The work is dominated by shades of blue, contributing to a sense of tranquillity and quiet, gently balanced with traces of amber pigment. Yang’s enthusiastic and intentional use of varying brush strokes blur the line between abstraction and pure representation, enlivening the painting with a distinct kind of musicality. Live models can be considered vulnerable both in their positionality as subject to the artist, and also in their nudity. The vulnerability of this figure is amplified by their downcast gaze, and this relates to Yang’s observation of minority groups in society—how they are obligated to appear composed and undisturbed when, in fact, their beliefs and lived experiences are constantly being challenged. Significantly, the figure depicted is an elderly, disabled woman. This sort of artistic representation is important and rare. Elderly women, especially with a disability, are rarely depicted in art—and even rarer still in the nude. Yang paints this model with a deep empathy and grace, cultivating a sense of dignity for the represented figure.

As an artist, Yang is inspired by her family. She is passionate about feminist art history, and aims to tackle society’s prejudices against women using nude bodies in their pieces of work. The figure of the nude woman is being shown through Yang’s artistic gaze, and thereby exists outside of patriarchal pressures to perform. Through the considered use of colour, brushwork, and artistic generosity, the possibility of an exciting and powerful dimension is created—one where artist and subject alike are author to their barest truths.

FEATURE 11

ZOEY YANG

not Silent (2020) acrylic on paper 12 YIARA MAGAZINE VOLUME 11

(UNTITLED) LABOURERS

AIMÉE LEBEAU

13 FEATURE

14 YIARA MAGAZINE VOLUME 11

Aimée Lebeau is an interdisciplinary, mixed-media artist in the Art Education program at Concordia University, and has a previous degree in Painting and Drawing. Lebeau’s works are born from explorations of various materials and approaches to artmaking. Lebeau’s earlier works have a memoiristic quality, tending toward figurative painting. In these works, she used fragmented memories and familial photographic archives to weave unique visual narratives. A more recent focus of the artist has been to generate an intentional union of a distinctly painterly visual style with fibre-based materials and practices, including reclaimed and recycled fabrics. Her explorations in fibres led to the production of Untitled (Labourers). In this work, Lebeau mined the gap between the different mediums. She says, “I was interested in exploring the dichotomy between painting and textile, and how historically, painting has been more of a male-dominated field, whereas textile work has been seen as women’s work.” Within and beyond art history, craft has often been relegated to a status of lesser art. Typically performed by women and non-male groups and individuals, craftwork (including textile work, ceramics, and other so-called “decorative arts”) has not been as valued as “high-art” forms such as oil painting. This is especially true within the Western art historical canon. In Untitled (Labourers), Lebeau wanted to dissolve the boundaries between textile work and painting to create a dialogue between the two. This work was created in Lebeau’s home, while she was sick with COVID-19. Limited by a lack of access to her school’s studios, she created a remote screen-printing set up and got to work. The ‘painting’ in this work was also screen-printed, but on canvas with acrylic paint. The repeated pattern that makes up Untitled (Labourers) is an original motif.

Seen from a distance, it resembles a decorative floral design, but a closer look reveals a series of interconnected figures. This complex visual pattern highlights the hidden labour behind the production and manufacturing of various materials used in artmaking—often taken for granted in the process of creating work. Lebeau grounded her ideas in Canadian women’s scholar Gail Cuthbert Brandt’s essay, “Weaving it Together: Life Cycle and the Industrial Experience of Female Cotton Workers in Quebec, 1910-1950” (ca. 1981). Other sources of visual inspiration included various modern and contemporary artists, such as Anni Albers and Yayoi Kusuma.

Untitled (Labourers) is a complex and layered work, and reveals Lebeau’s broader conceptual concerns, bringing to light various tensions in art history and art production. The artist wanted to probe the placement of societal values to visualize the ubiquity of the textile medium and the simultaneous indifference to the labour behind its production.

15 FEATURE (UNTITLED) LABOURERS

16

FEATURE 17

MOUNTAIN GIRL

Maral Matig is a second-generation Armenian and Canadian-born artist, currently studying Design at Concordia University. Matig has used her art practice as a means of healing, and it has simultaneously given the artist an opportunity to connect with her Armenian heritage on a deeper and more significant level.

Matig has a desire to centre themes of cultural awareness, and bodily freedom and expression, in her works. “The past two years have been a rerouting of self for me. I struggle with anxiety and my culture has helped with my healing, and has given me a sense of purpose,” says Matig.

Mountain Girl, a title inspired by an Armenian folk song, is a mixed media work that began as a gouache painting, and was later scanned on to Photoshop where Matig inverted the work and added other digital elements. This mix of material and digital elements results in a work that emits a special kind of illumination, highlighting the artist’s unique process. Matig feels that digital art is often relegated to a category of lesser art, but she believes that using digital processes allows her to extend her painterly vision beyond the physical limits of canvas.

Another integral aspect in Matig’s works is the artist’s relationship to landscape: “I developed an attachment to the Armenian landscape by looking at pictures of it. I developed a strong bond with the land just through digital imagery.” When Matig finally got an opportunity to visit this landscape, she experienced a visceral attachment to it and felt an urgency to represent her experience in her art. Seeing the undulations of her own shadow upon the Armenian landscape, Matig explained that “Indigenous Armenian bodies are rooted in the land and they come out of it when the sun sets. For me, a diasporic person, art is a way for me to preserve the [home]land.”

There is an emphasis on colour and line in Mountain Girl, and different figures emerge in this mix. They are ethereal figures, but they are not necessarily roving or untethered. Matig’s intention is to emphasize the connection between body and land, and the relationships of these two entities to generational trauma and healing. Mountain Girl is a product of discovery - a moment in which the artist was able to sink into the freedom of recognizing new or hidden parts of oneself.

MARAL MATIG

18 YIARA MAGAZINE VOLUME 11

ARCHIVING THE CLUB: THE DANSEUSE NUE GRAPHIC MEMOIR OF SYLVIE RANCOURT

Typing the words “Canada sex workers comics” into any search engine will inevitably lead you to Chester Brown’s acclaimed graphic novel, Paying For It. It’s ironic that the first (and almost only) book we encounter is written by a man, a client, and above all an outspoken hobbyist review board member.1 Brown, like other hobbyists, is a certain type of “John;” a client of sex workers who makes a hobby of reviewing and writing lengthy resumés of their encounters for other client-board members to evaluate. Is it surprising that a client wrote the most popular graphic novel on sex work? Where are the sex working cartoonists, and do they even exist? Using the career of Sylvie Rancourt as a leading example, this essay centers sex workers themselves in the Canadian landscape of graphic memoirs, comics and illustrated zines. Exploring themes of feminism and queerness within Rancourt’s oeuvre, I document the importance of self-publication and archiving as queer methodologies. Rancourt deserves recognition as a pioneer of graphic memoirs and sex worker literature, and this essay ultimately seeks to dethrone Brown as a pioneer in the genre.

An Introduction to Mélody

Internationally renowned, Sylvie Rancourt is a cartoonist, painter, and illustrator from Abitibi in Northern Quebec. She started to produce and self-publish her comic series Mélody while stripping in Montréal and small towns of Québec, documenting the comical misadventures of its titular character and photocopying them to sell to her clients at stripclub tables. Sex workers develop many skills that are not often recognized; as Eleanor Ty expresses, “not only was she an artist, illustrator, and writer, she was also a distributor, publicist, and saleswoman.”2 The Mélody series embodies the very unique characteristics of 80s Québec’s danseuses nues culture and the multifaceted dimensions of informal underground economies. Gaining little visibility through Québec newsstands and television programs, Rancourt faced many obstacles concerning her subject matter, including censorship, and did not reach notoriety during her time dancing the tables in Montréal.

19 IN CONVERSATION

BILLY HOUDE

I am not the first one to contrast Rancourt’s work to Chester Brown’s. Feminist cartoonist Julie Delporte stated in an hommage letter to Rancourt that she “almost laughed when [she] learned that [Rancourt] would be published by Drawn & Quarterly: Mélody became to [her], became the anti Paying For It.”3 Opposed to Paying For It, which tries to justify and politicize Brown’s use of sex workers’ time, Mélody simply exists; she is there to entertain and has no agenda behind the strips. Delporte notes that Mélody’s portrayal as a stripper is “devoid of propaganda of [herself], nor a victimization of [her] self, despite adventures that are sometimes demanding.”4 While Rancourt has often stated that she does not identify as a feminist, Delporte reminds us that “Chester Brown speaks of a topic that I don’t want men to speak about anymore, while I would like to put a pencil in the hand of every women experimenting sex work, from close or afar.”5 This comment highlights the political value of Rancourt’s work in de-stigmatizing sex work as presenting it as just ‘work;’ Mélody is the comical journey of a young working class francophone woman in the eighties.

Ty also contrasts Rancourt’s depictions of sex workers to those of Brown in “The un-erotic dancer: Sylvie Rancourt’s Mélody,” in which she offers a close analysis of the graphic memoir’s unique style and visual details. She notes that in order to maintain their anonymity, Brown chooses to not detail faces, but provides details of the lives of the sex workers he visits.6 This creates a mechanical effect in which sex workers are shown in an almost robotic, dehumanizing manner, where sex is just practical. Brown, devoid of emotion, does it to fulfill his needs. While stylistically the original drawings of Mélody are very simple and coded as naive, strong emphasis is put on each woman’s individuality. Ty notes that this is explicitly clear in how Mélody is portrayed as a creative woman, at one point even creating a stripping show with puppets.7 Unlike the women Brown visits, Mélody has various relationships with people; her deadbeat boyfriend Nick, her family, Nick’s Aunt, and other dancers she befriends, including Louiselle, a character with whom she also develops a romantic and sexual friendship.8 Mélody showcases the complexities of life for a rural woman living on low-income, while remaining hopeful and adapting to the various challenges she faces.

Censorship, Self-Publication and Mainstream Media

Rancourt’s particularly queer methodology lies in the DIY nature of her work. Mélody was self-produced, primarily due to monetary restrictions, but also because the nature of the work was extremely taboo at the time. Self-publishing allows the creator to escape censorship, something Rancourt often faced when she attempted to reach larger audiences and work with publishers.

After the success she encountered with stripclub audiences (both customers and dancers), Rancourt self-published six issues of Mélody in French in 1985, with covers illustrated by Jacques Boivin and distributed in Quebec newsstands. A seventh issue called Mélody en Cadeau didn’t make it to the newsstands, as pro-

20 YIARA MAGAZINE VOLUME 11

duction was costly, but did appear in the 1989 edition Archives Mélodie 1 à 7 published by Montréal underground cartoon press, Éditions du Phylactère.9 Bernard Joubert notes that as early as 1986, Rancourt received criticism for her work.10 In an open letter published in Le Journal de Montréal, columnist Solange Harvey wrote: “I respect you as a person and acknowledge the duties of your work. However I see no utilities whatsoever in your turning it into a pornographic publication. That’s unfortunate for you. Don’t count on any free publicity. You’ve fallen into mediocrity and facility.”11

The first English translation of Mélody occurred in 1988, when Rancourt and Boivin collaborated on a new Mélody series distributed through Kitchen Sink Press. To make Mélody appealing to an American audience, Boivin illustrated the comics in his illustration style which was less naive. Kitchen Sink Press published ten volumes of Mélody, as well as a collection called The orgies of Abitibi, which sold one hundred and twenty thousand copies.12 This success could have likely been echoed in Canada, but Rancourt faced controversy after the American magazine Family Circle denounced her books as “pornography in the guise of cartoons” in the early nineties.13 Despite the fact that Mélody was always distributed to an adult audience, the statement had repercussions in Canada where the bookstores distributing Mélody were targeted. Four employees of the small comic bookstore Planet Earth in Toronto were convicted of “possession and sales of obscene material,” leading to its permanent closing. About a month later, the Toronto Morality Squad raided another bookstore, seizing over four hundred Mélody magazines.

Fig 1. Mélody à ses débuts, first self-published edition, 1985. Collection Nationale.

Fig 1. Mélody à ses débuts, first self-published edition, 1985. Collection Nationale.

IN CONVERSATION 21 BILLY HOUDE

Fig. 1. Sylvie Rancourt, Mélody à ses débuts, first self-published edition, 1985. Collection Nationale.

Andromeda, the company distributing Mélody in Canada at the time, was also raided shortly after and stopped distributing any material that could be described as “pornographic.”14 As a result, boxes of Rancourt’s work were sent back to her which influenced her to stop working on comics. In 2011, Mélody was redistributed by a Fantagraphics sub-division called Eros Comics throughout the United States and other countries, but could not be distributed in Canada due to censorship laws.15 According to Delporte, the defunct Montréal bookstore Fichtre (1996-2010) sold handbound anthologies of Mélody but they were very expensive and thus quite inaccessible.16 In 2013, Mélody was re-edited in its entirety in France through Ego Comme X editions, and it is only thirty years after its creation that in 2015, Mélody was made widely available in an English translation in Canada through the Montréal press Drawn & Quarterly. Most recently, Mélody was published by Spanish independent press, Autsaider Comics, in February 2022, who released a Spanish translation of the original comics as an anthology named Mélody: Diario de Una Stripper.

Rancourt self-published a wide array of comics and fanzines under her own label, Editions Mélody as well, including one thousand copies of the first edition of Mélody à ses débuts, printed in black and white (fig. 1). Éditions Mélody also birthed the six issues of Mélody that were distributed in Quebec newsstands, and Boivin explains that these editions were made to look more “professional.”17 Despite her retirement from stripping in later years, Rancourt continued to distribute her own work through various means. According to her Wikipedia page, she self-published many other zines in the nineties and early 2000s, including Club Mélody, Cheveuton, La Bible selon Sylvie Rancourt, L’Espoir, Bébé Mélody and Mélodie burlesque. Some of these zines can be retrieved at the National Collection archives of the National Library, as well as others which are not retraceable online. Her work has also been sold through the Montréal feminist bookstore L’euguélionne. To this day, Rancourt runs an Etsy shop where she sells original paintings (fig. 2), self-publications, and vintage Mélody memorabilia such as playing cards, a direct clin d’oeil of sex work culture in the eighties and early nineties. She is also known to make appearances at underground comic book festivals and national comics events.

Queerness and Mélody

When speaking on the queerness aspect of Mélody, it is useful to remind ourselves of this Jon Davies quote on queer curation: “I hope that ‘queer’ will always retain its associations with non-normative genders and sexualities, but it’s most important for me as a kind of doubled vision, a way of looking askance at the world—having a heightened, critical sensitivity to the fiction we live under and that shapes us.”18

Sex workers share this doubled vision with queer people, and we see this in how Rancourt’s unique perspective produces the result of her various marginalized identities combined—a stripper, a woman who wrote about sexuality despite censorship, and a working-class rural woman who left to the city due to lack of opportunities in her

22 ARCHIVING THE CLUB YIARA MAGAZINE

mining town. As Davies puts it: “Whether artists (or curators) use the word “queer” or not, I feel a kinship with those holding onto a sense of difference and apartness that evolves over time, people who consciously align themselves with past and present struggles and queer touchstones.”19 While queer people have always existed, the generation Rancourt is from—northern Québécois working class, didn’t use descriptives like queer to illustrate their lived experiences. Nonetheless, a queer affect is found in Mélody. Questions of sexual exploration and curiosity are omnipresent through Mélody. In Mélody et ses Orgies, she develops a close friendship with Louiselle and asks herself if she is a lesbian. In footage from a TQS Camera 87 segment about Rancourt and her work, this specific strip is shown on the screen. Twenty-nineyear-old Rancourt answers the host’s questions, claiming that orgies are now common, and that she likes to pick a girlfriend from time to time.20

In Mélody et ses orgies, Mélody and Louiselle become close to each other at work, and they end up living together with Nick and Louiselle’s boyfriend and children because they are not making enough money at the club. Ty notes that when the orgies are illustrated, the men are at the edge of the bed while Mélody and Louiselle are in the middle, which puts a strong focus on their connection.21 Mélody and Louiselle later on perform lesbian shows at the club, and Mélody finds herself desiring Louiselle.

A clear link can also be made between sex workers and queer communities as both are portrayed as deviant and highly criminalized. The criminalized aspect of queerness in the seventies and eighties is clearly expressed in a short video made to educate against discrimination towards LGBTQ+, where Rancourt explains that she “drew from the sexual orientation of the

mid seventies.”22 Not only is queerness depicted in various aspects of Mélody’s adventures, but it is also deeply ingrained in the way Rancourt talks about sexuality and friendships. In her personal life, she had a close relationship with her brother who was gay and cross-dressing in the seventies. Rancourt explains that they would drive from Abitibi to Montréal together and that he would go to “gay, trans bars; that were very discreet, almost secret.”23 He died by suicide when she was fifteen. It is within this context in Abitibi and Montréal that we see the perception of queerness translated in Rancourt’s artwork.

Conclusion: On Archiving Sex Work Culture and the Legacy of Mélody

On the infamous Camera 87 episode, we see Rancourt entering the strip club L’axe in Montréal. Throughout the interview that was broadcast on TQS, we can observe her doing various things candidly, including working on her comic, calling distributors, and nude dancing. Club L’axe, which has recently closed, was one of the few remaining stripclubs of the era when Rancourt was dancing.24 The stripclub industry in Quebec has undergone changes partially due to lockdowns and limitations caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.25 Radio-Canada affirms that there were about two hundred strip clubs in Québec over a decade ago, and now there are about one hundred remaining. It is a business that is not as profitable as it was in the eighties, and sex workers are now turning to different options out of necessity.26 These establishments are part of Québec history, but also of local sex worker culture. Sylvie Rancourt’s work is a testimony of this era and is an important archive for the iconic universe of the notorious danseuses nues of Montréal and Québec.

23 BILLY HOUDE IN CONVERSATION

NOTES

1. Escort Review Boards are common for Canadian cities, and are platforms where clients (calling themselves hobbyists) write lengthy reviews of escorts they hired. These reviews can include physical description, age, and the services provided. While some service providers use these forums to advertise, a vast majority of sex workers are critical of review boards.

2. Ty, Eleanor. (2018). “The Un-Erotic Dancer: Sylvie Rancourt’s Mélody.” In Comics Memory: Archives and Styles, edited by Maaheen Ahmed and Benoit Crucifix, 121-141. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

3. Translated from French: “J’ai presque ri en vous apprenant publiée par Drawn & Quarterly : “Mélody est devenue pour moi l’anti Paying For It” (a comic strip memoir about being a John); Delporte, Julie. “lettre à sylvie rancourt.” La Cité internationale de la bande dessinée et de l’image, 2015. http://neuviemeart.citebd.org/spip.php?article1232.

4. Translated from French: “Dans Mélody, il n’y a à l’œuvre ni propagande de vous-même, ni victimisation de votre situation – et ce malgré des aventures parfois éprouvantes.” Delporte, “lettre à sylvie rancourt.”

5. Translated from French: “Chester Brown y parle d’un sujet sur lequel je ne veux plus entendre les hommes s’exprimer, alors que j’aimerais mettre un crayon dans la main de toutes les femmes expérimentant de près ou de loin le travail du sexe;” Delporte, “lettre à sylvie rancourt.”

6. Ty, “The Un-Erotic Dancer,” 122.

7. Ty, 135.

8. Ty, 125.

9. Boivin, J. Préface to Archives Mélody 1 à 7 by Sylvie Rancourt. Éditions du Phylactère, 1989.

10. Joubert, Bernard. “High Culture and Good Manners Be Damned.” Afterword of Sylvie Rancourt’s Mélody: Story of a Nude Dancer. Translated by Helge Dascher. Montréal: Drawn and Quarterly, 2015.

11. Joubert, “High Culture.”

Fig 2. “Festival Guay #3”, Acrylics on Canvas, 2012. On this canvas, we can see Rancourt herself with a ghostly Melody. Note the spelling “guay” - spelling mistakes are common in Rancourt’s work, which can be understood as a particular style of Quebecois working class language. Retrieved from https://www.etsy.com/ca/shop/melodybandedessinee

12. Dee, M. “Sylvie Rancourt: Cartoonist.” Constellation 5-6, no. 1 (N.D.). Stella L’amie de Maimie.

13. Dee, “Sylvie Rancourt.”

14. Dee, “Sylvie Rancourt.”

15. Dee, “Sylvie Rancourt.”

16. Delporte, Julie. “lettre à sylvie rancourt.”

17. Boivin, Préface to Archives Mélody 1 à 7.

18. Barbu, Adam. “Queer Curating, From Definition to Deconstructing.” Canadian Art, 2018. https://canadianart.ca/features/queer-curating/.

19. Barbu, “Queer Curating.”

20. Camera 87. Feb 7, 2014. Melody 87 (video). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0vc9Jk_Ua4g.

21. Ty, “The Un-Erotic Dancer,” 136.

22. Translated from French: “J’ai dessiné l’orientation sexuelle des années 1975.” Commission des droits de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse, 2020. https://www.youtube. com/watch?v=0AYuvu083YE.

23. Translated from French: “Mon frère allait souvent dans des bars gais, trans. C'était des bars très discrets, presque secrets.” Commission des droits de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0AYuvu083YE.

24. Club L’axe has closed business since writing this piece, marking the ongoing mass closures of strip clubs in Montréal.

25. Quirion, René-Charles. “Quelles sont les conséquences du déclin des bars de danseuses érotiques?” Ici-Radio Canada, February 4, 2022. https://ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/1859877/effeuilleuses-declin-nudite-etablissement-estrie

26. Quirion, “Quelles sont les conséquences.”

Fig. 2. Sylvie Rancourt, Festival Guay #3, acrylic on canvas, 2012. Retrieved from https://www. etsy.com/ca/shop/melodybandedessinee.

24 YIARA MAGAZINE ARCHIVING THE CLUB

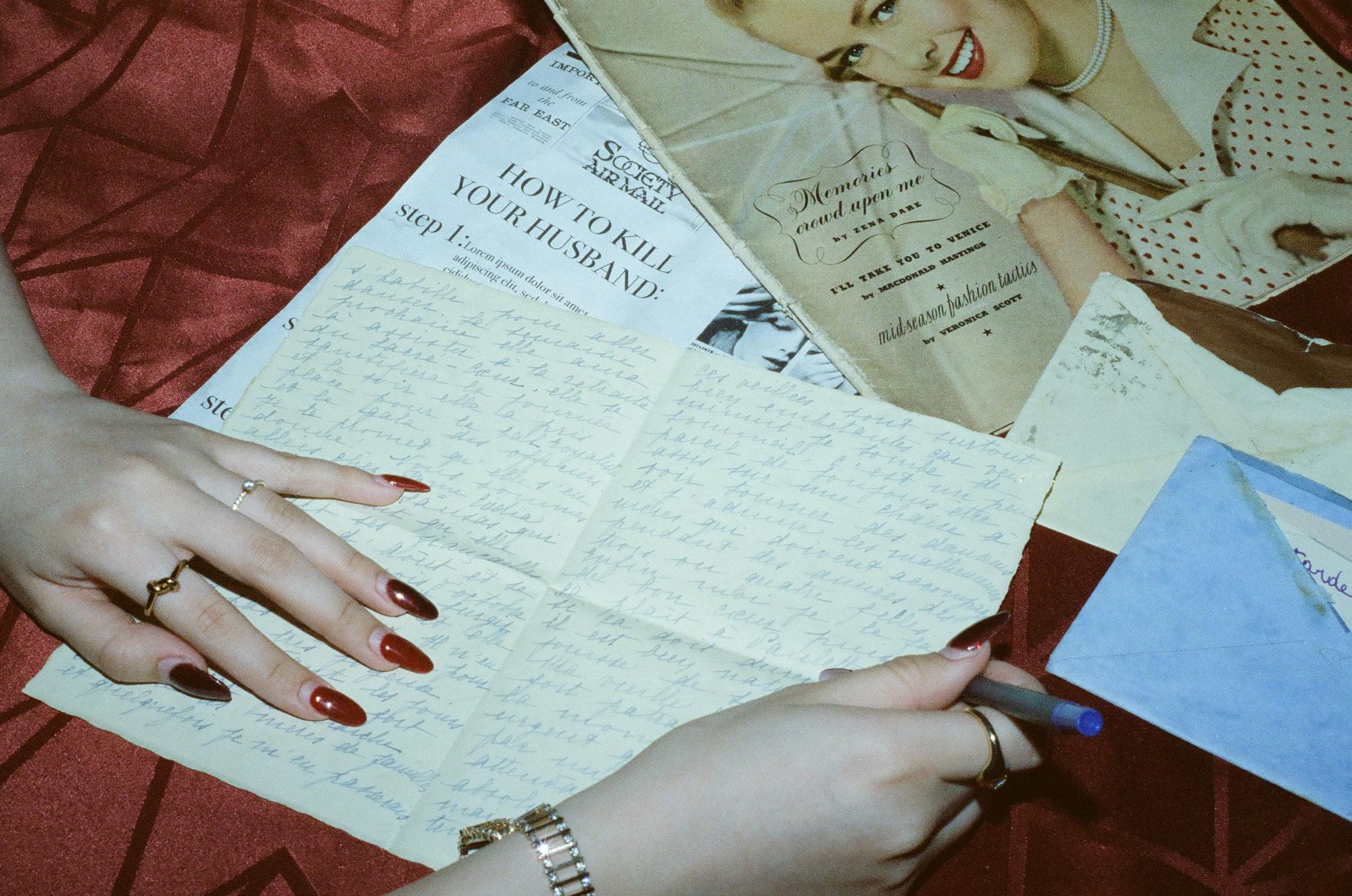

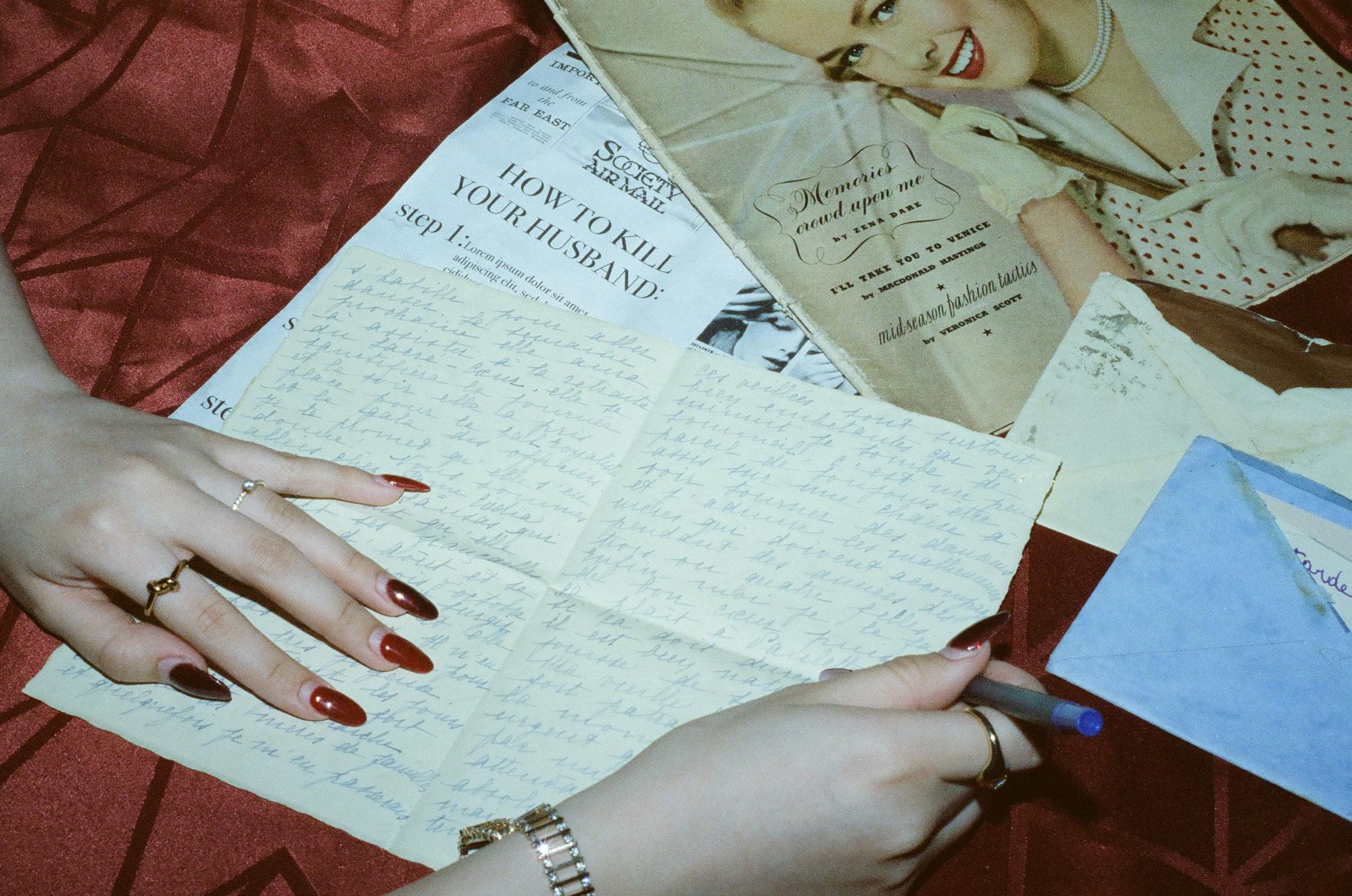

ALEJANDRA

NESREEN GALAL

Nesreen Galal is a Montreal based interdisciplinary artist currently studying Computation Arts and Studio Arts at Concordia University. Galal has an interest in art directing and mise en scène, and the ways in which a unique and distinct world can be created within FEATURE and images. Galal chose Alejandra on FEATURE, and manipulated lighting and set design in order to create a surreal and uncanny atmosphere —two dominant themes in this work.

Galal’s Alejandra is a contemporary, intersectional feminist reimagining of the femme fatale trope inspired by campy movies and retro FEATURE noir movies like Gilda and Laura. The work is a series of prints presented to resemble FEATURE stills, wherein a BIPOC Latina is presented to the viewer through a distinctly female gaze.

Galal aimed to deconstruct and confront the whitewashed archetype of the femme fatale presented in classic Hollywood FEATUREs, typically wrought by a dominating and sexualizing male

gaze. Galal references feminist FEATURE theorist Laura Mulvey’s seminal text, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975), and Mulvey’s conception of the gaze in cinema. Historically, women in cinema have been distorted through the objectifying looks of the camera, FEATUREmakers, and the audiences of FEATUREs—typically conceptualized as male. Women’s bodies and subjectivities, idealized and reduced to a point, perform simply as conduits for the narrative trajectories of the masculine hero. Galal explains, “I’m playing with the fragments of the femme fatale image, and opening new approaches to it.”

In Alejandra, Galal confronts this gaze and boldly subverts it by presenting her audience with a feminine, self-defining hero. The narrative of the work is mysterious and unclear, but this is not the central focus of the work. Instead, one is invited to look closer and to experience the energy generated by Galal and her subject—one that doesn’t rely on an objectifying gaze.

FEATURE

25

26

27

28 ALEJANDRA YIARA MAGAZINE

29

ALEJANDRA YIARA MAGAZINE 30

FEATURE NESREEN GALAL 31

32

FEATURE NESREEN GALAL 33

ALEJANDRA YIARA MAGAZINE 34

FEATURE NESREEN GALAL 35

ALEJANDRA YIARA MAGAZINE 36

FEATURE NESREEN GALAL 37

38

“Be Daring, Darling”

Rianna Gurevitch

POETRY

39

allow your arms to drape across my chest with intention:

you want to see their awe, you want to see their revolt.

wisp your willowy words across my ear, mocking their despair with your divine tongue. among a dinner of damaged hearts, I’d adore seeing their heads twist and warp into gooey brain parts as they see you sipping burgundy-stained lips, my only reason to breathe in disdain.

tug the torso of my blouse as I bless the mess of your mouth

swallow my swollen smile make a spectacle of our love for the first time.

there’s purpose in privacy but sorrow in secrecy.

could we forget the frightening and proceed seamlessly?

sink your nails into the nape of my neck grip onto a hopeful reality

they will take our crimson insides and throw them in our faces we’re fighting for an oath we can’t guarantee they’ll make we’re jaded in our love, careful where we lay it if it’s become too much, maybe we’ll forfeit

so I’ll wipe the tears as they fall into my wine as I burn their faces in my mind.

40

“It’s something that has a heavy double meaning.”

TENNIS SKIRT

HANNAH BERGER

FEATURE 41

YIARA MAGAZINE VOLUME 11 42

Hannah Berger is a student in the Art History and Studio Arts program at Concordia University. Her sculpture Tennis Work is a conceptual work that depicts a seemingly mundane item of clothing, but works to unearth the charged symbolic possibilities that can exist in such objects. Berger shares, “I was interested in the tennis skirt as something that is both a symbol of youthful femininity, and, removed from its original context, has been transformed into a sexualized fetishistic object. It’s something that has a heavy double meaning.” In creating this project, Berger echoed the symbolic weight of this object in the material used to create it. Tennis Skirt is casted in bronze, born from an arduous process that has been used to create the most highly-valued art in history, especially in classical sculpture. Bronze is the material of monuments; it has long been used to honour individuals and events that have been collectively deemed culturally significant. Keeping this historic material practice in mind, Berger set out to create a work that memorialized the experiences that young, contemporary women often face as they navigate the internet and a world that relies on the widespread, commercialized oversexualization of female bodies.

FEATURE HANNAH BERGER 43

Of her own experience, Berger says, “I grew up on the Internet on various image-based sharing platforms where you’re just bombarded with images of sexualized women. [At those impressionable phases in my life], my brain was absorbing those very powerful, gestural, and sexual images. And your sexuality and sense of self are contrived from exposure to those kinds of images.” Self-objectification or habitual body monitoring, a theme explored in Berger’s work, is one of the main effects of being continually and relentlessly exposed to a visual language that privileges patriarchal conceptions of ideal embodiment of womanhood.

Berger accentuates her interest in the visual language of antiquity by likening Tennis Skirt to a Roman kilt. The sculpture is disintegrating, but it remains intact. The choice to display this sculpture on the floor is not an insignificant one; Berger is speak-

ing to our societal desire to valorize the individuals depicted in monuments, while at the same time, femme bodies are often treated as conduits through which certain subsects of society can assert dominance and power over the very bodies they are wielding.

Tennis Skirt also points to the dichotomy of material value we place on ostensibly permanent objects such as bronze monuments, and contrasts it with the disposable and infinitely replaceable status that underscores the manufacturing of fast fashion. Berger calls attention to the fact that these societally agreed-upon value scales are not neutral, but a result of societies that are shaped around patriarchal standards. With this sculpture, Berger invites us to contemplate these layered and nuanced considerations of how our social worlds are formed.

YIARA MAGAZINE TENNIS SKIRT 44

Kinda Focused on Being Adorable Right Now

Havana Xeros

IN CONVERSATION 45

Cuteness is rooted in visual commodi ties rather than the language of the arts. Unlike its avant-garde counterpart which is characterized as sharp and cutting-edge, cuteness can’t speak, has no harsh edges, and is usually infantile and feminine. It is an evolutionary adaptation that primes our minds and bodies for fun and sociable interactions.1

The indoctrination of cuteness is explained by Morten L. Kringelbach et al. in their study, On Cuteness: Unlocking the Parental Brain and Beyond, as a physiological phenomenon that has been linked to an increase in empathy, motivation, and mental performance.2 We are currently in an empathy gap post-pandemic, where we struggle to predict emotions in ourselves and others because we underestimate how our innate behaviors influence us. Society sees comfort in the familiar, which often resides in cuteness. What does this mean for society? How is cross-cultural cuteness shifting and in what ways does it emerge to fit our needs?

According to Sianne Ngai’s article The Cuteness of the Avant-Garde, terms such as cute, whimsical, and cozy emerged during the rise of consumerism.3 The rapid development of new commodities with a focus on design and advertising came about around the mid-twentieth century, when cuteness became a descriptor, not just for objects but for people as well. Cuteness as a term was used mostly in relation to physical appearance and applied to diminutive persons. The descriptor was later associated with femininity, culture, and national differences between the East and West.

Behavioural psychologists have separated cuteness into two categories—one that

is childlike and associated with vulnerability, caretaking, big eyes, and softness. The oth er is whimsical, fun, and indulgent. The baby cuteness aesthetic is very dependent on touch. Small, malleable, and soft are some adjectives that embody what society deems cute. Konrad Lorenz, an Austrian ethologist, coined the term “baby schema” to represent a phenomenon motivating caretaking behaviours and affecting women more heavily.4

Round and simple visual properties leave space for interpretation and relatability, allowing people to imagine characters with these features are feeling emotions with you. Simple, unformed faces with little detail become rounder and therefore cuter (e.g. miffy). Characteristics such as helplessness and pitifulness mixed with properties of softness and simplicity create the perfect formula for cuteness according to Lorenz.5 This formula is amplified by the depiction of grogginess and the act of eating, seen in characters like Winniethe-Pooh with his jar of honey, or toddlers who wipe their eyes after waking up from a nap. At the same time, cuteness has the tendency to be hyper-objectified, dehumanizing subjects into objects. These are all characteristics of cuteness that have existed for years and are often similar between most cultures.

Philosopher Daniel Harris points out the anthropomorphism involved in cuteness. He defines “the narcissism of cute” as a “world without nature, one that annihilates ‘otherness,’ ruthlessly suppresses the nonhuman, and allows nothing, including our own children, to be separate and distinct from us.”6 Cuteness here can develop into a personification strate gy for otherness while making us assign feel ings such as vulnerability, pain, and the need

YIARA MAGAZINE VOLUME 11 46

for protection. This manifests in the real world through non-human objects with faces, such as Gudetama, a personified egg demonstrating that food can be presented as cute.

Before anything, the intention of cuteness is a taste quality aligning with products for children. Once children began being perceived as separate from adults in the twentieth century due to the influence of child labour rights, cute toy objects appeared on the market to control children’s aggressiveness, according to Sianne Ngai.7 The American toy industry began using dolls to teach domestic skills, and the use of malleable materials would allow children to express aggression by squishing and throwing. Toys and concepts such as the emergence of Kewpies, a brand of dolls and figurines deriving from cartoonist Rose O’Neill, were far from helpless. These baby-like characters acted as a social reformer, educating mothers and helping end children’s welfare as society started to view children as more vulnerable and innocent than adults.

In Japan, cuteness, or Kawaii culture, accelerated the development of society as a whole, reaching not just the toy industry, but also industrial design, print culture, fashion, food and more. Japanese post-war fascination with Kawaii emerged as a way to express inferiority in the monarchy, which grew into a violent aesthetic seen in the work of artists like Takashi Murakami.8

Kawaii is the Japanese ideology of cuteness, originating from the word kawahayushi, a term used to describe sympathy and pity towards more vulnerable members of society such as children. The trend took off in the early 1970s with the emergence of a new childish handwrit

ing style influencing a large number of teenagers in high school, especially women, as explained in Sharon Kinsella’s article Cuties In Japan. 9 From this childish handwriting, infantile slang became widely used, furthering the Kawaii aesthetic into what it is today with an emphasis on characters from Sanrio products, cosplay, small finger foods, and anime.10 To this day, Kawaii is associated with the fantasy of remaining young, being shojo (an unmarried woman), and having no responsibilities. This was seen as a form of rebellion, similar to how punk was used by teenagers in the West. Japanese toy icons such as Nara, Hello Kitty, and Kogepan appealed to every age group, not just children, bringing the concept of cuteness to adults. Psychological studies corroborate this, such as a 2011 record stating that even babies and children prefer cherubic faces, and that cuteness affects both men and women even if they’re not parents.11 This research further drives the idea that cuteness is a universal experience.

With cuteness manifesting itself in channels such as playful, child-like clothing and visually compelling media, a link between cuteness and pleasure is evident. This association has opened up the possibility for cuteness to be sexualized. This is a common argument against the merits of cuteness, known as the anti-cute argument according to Ngai. In this sense, cuteness can be seen through modernist writer Gertrude Stein’s perspective as “anything but precious or safe” in her book Tender Buttons: Objects, Food, Rooms 12

Cuteness as a fashion aesthetic has been criticized for encouraging girls and young women to act submissive, weak, and innocent rather than mature, assertive, and independent. The criticism culminates in the switch in male

IN CONVERSATION 47

HAVANA XEROS

post-war pornography from glorifying motherly roles to childlike roles. Thus, cuteness is often referred to by the anti-cute as a fetishistic aesthetic.13

Mainstream Japanese culture views cuteness as a distraction for working adults. Cuteness is heavily correlated with indulgence and overconsumption. Young people are caught up in collecting items and cosplaying, leading to a negative impact on both the environment and consumers’ wallets. Governments and other forms of authority have used cuteness in the form of mascots to distract from war crimes and anti-humanitarian activities. In an article by Neil Steinberg, he states rather than being perceived as a figure of authority, the government wants you to believe they are your friend.14 This is seen in examples such as Pipo-kun, the Tokyo Police mascot.

Based on the pervasiveness of cuteness in several cultural domains, it is no surprise that globalization and the desire to appear cute is flooding aesthetic and fashion choices for teens and young adults. We are seeing the influence of queer independent FEATURE director Gregg Araki’s saturated fashion and lifestyle aesthetics, maximalist Harajuku fashion seen in media like Fruits Magazine, Marc Jacobs’ Heaven fashion label, and introspective dreamscape

NOTES

1. “Cuteness and Science.” Cute Studies. Accessed March 25, 2023. https://www.cutestudies.org/cuteness-and-science.

2. Kringelbach, Morten L et al. “On Cuteness: Unlocking the Parental Brain and Beyond.” WTrends in cognitive sciences 20, no. 7 (July 2016): 545-558. doi: 10.1016/j. tics.2016.05.003.

3. Ngai, Sianne. “The Cuteness of the Avant-Garde.” Critical Inquiry 31, no. 4 (Summer 2005): 811-847.https://doi.org/10.1086/444516.

4. Glocker, Melanie L. et al. “Baby Schema in Infant Faces Induces Cuteness Perception and Motivation for Caretaking in Adults.” Ethology 115, no. 3 (March 2009): 257-263, 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2008.01603.x.

5. Glocker et al., “Baby Schema.”

6. Harris, Daniel. Cute, Quaint, Hungry And Romantic: The Aesthetics Of Consumerism. New York: MJF Books, 2000.

7. Ngai, “The Cuteness of the Avant-Garde,” 817.

8. Ngai, “The Cuteness of the Avant-Garde,” 834.

worlds in cover art by Drain Gang and other hyperpop musicians. The aesthetic imagery of new-age cuteness is all-encompassing and has contributed to the online revival of 2000s subcultures, like emo and scene kids.

Cross-cultural cuteness is being considered post-pandemic as we long for the nostalgic comfort and bliss of childhood icons from the ’90s and early ’00s. Society is working on filling the deprivation emerging from the empathy gap, and cuteness acts as a method to separate fantasy from reality. Cuteness intersects vulnerability, yet it invites the potential for increased passivity.

Quintessentially cute traits can cause the chemical release of dopamine and oxytocin through long hugs, but can also excite an individual’s sadistic desire used for mastery and control because people lose the ability to think critically around cute things. Perhaps the adoption of cuteness allows people to manage feelings of powerlessness built around their production of capital during times of political turbulence. It creates political imagination, a vision about the capacity to create and inhabit an otherwise embodied persona of toys, playfulness, and vulnerability. It’s a surrender of dignity and a violent kind of delightfulness.

9. Kinsella, Sharon. “Cuties in Japan.” In Women, Media and Consumption in Japan, 220-254. New York: Routledge, 1995.

10. Sato, Kumiko. “From Hello Kitty to Cod Roe Kewpie: A Postwar Cultural History of Cuteness in Japan.” Association for Asian Studies 14, no. 2 (Fall 2009): 38-42. https:// www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/from-hello-kitty-to-cod-roe-kewpiea-postwar-cultural-history-of-cuteness-in-japan/.

11. Parsons, Christine E. et al. “The Motivational Salience of Infant Faces Is Similar for Men and Women.” Public Library of Science 6, no. 5 (2011): e20632. 10.1371/journal. pone.0020632.

12. Stein, Gertrude. Tender Buttons Objects, Food, Rooms. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications,1997.

13. Harris, Daniel. “Cuteness.” Salmagundi, no. 96 (Fall 1992): 184-186.

14. Steinberg, Neil. “The emerging field of cute studies can help us understand the dark side of adorableness.” Quartz. July 24, 2016. https://qz.com/740598/the-emerging-fieldof-cute-studies-can-help-us-understand-the-dark-side-of-adorableness.

YIARA MAGAZINE KINDA FOCUSED ON BEING ADORABLE RIGHT NOW 48

“Ce qu’ils ne peuvent pas nous prendre...”

Emma Morselli

POETRY

49

Qu’il n’y ait personne au monde, ou que l’on n’existe pas Un ressenti de se faire contrôler dans la souffrance

Que la terre meurt, ou pas

La marche qu’elle a manquée

Une cheville foulée

Des larmes océans, et des bleus salés

« C’est pas moi »

Bien qu’ayant tout perdu

Le savoir, soufflé par un vent empoisonné

Tout ce qu’elle savait

Volé, envolé

Une voiture qu’elle a trouvée

La roche lancée

Des menottes aux poignets

« C’est pas moi »

Ce que personne ne prend Pris au piège dans certains virages, visages

C’est ce qui fait voir, parler, crier, Puis retomber.

50

AQUI ESTAMOS

FEATURE

51

(HERE WE ARE)

YIARA MAGAZINE VOLUME 11

ARANTXA MARTINEZ DUGAS 52

A qui Estamos is a series of paintings and performances by artist Arantxa Martinez Dugas which were produced as a means to bring attention to the issue of femicide in Mexico, the oversexualization of the female body, and the corresponding frustration and hope that accompany such brutal and enduring phenomena. Dugas, who is originally from Mexico, moved to Montreal when she was eighteen, and the artist is currently in her third year of a Bachelor’s degree in Studio Art at Concordia. Dugas has a long-held interest in collage and multi-media creation. Her current artistic explorations, along with painting and drawing, include sculpture work, as well as fibre and textiles.

A qui Estamos is a layered work that includes three paintings and a photographed performance (these are the images included in Yiara). Dugas began conceptualizing this work after attending an International Women’s Day demonstration in her home country. The women in Mexico use this day as an opportunity to take to the streets in protest, spreading a voice for missing women and victims of femicide. The bandanas worn by the performers in A qui Estamos, close friends of Dugas, had been worn during the demonstration. They function as a reference to the moment of inspiration for this piece, and to the intentions and goals of political gathering. As a whole, the artwork represents a form of protest, and functions as a memorial and tribute to the women who inspire the artist. With A qui Estamos, Dugas wishes to honour their experiences in the ongoing struggle against patriarchal oppression.

FEATURE ARANTXA MARTINEZ DUGAS 53

A 2021 study by Amnesty International found that, on a global scale, over fifty thousand femicides are committed each year. In her works, Dugas makes use of a dark strip of black around the eyes of the women photographed to showcase the enduring pain of victims and survivors. A profusion of power, defiance, and a thrilling lack of fear is clearly rendered on the faces of the figures. A qui Estamos echoes the unique and unmistakable energy and power of women coming together to fight for themselves and for each other. Infused with trauma, pain, hope, strength, and joy, this piece is abundant in its use of colour and movement. Dugas uses warm, vibrant colours to invoke a feeling of unity, compassion, and sisterhood. It is important to her that hope is equally represented along with grief. Dugas openly shares with Yiara the reality of Mexican women living under a corrupt government, and wishes to empower women across the world with her work, encouraging them to speak up, fight against fear, and band together in community.

This artwork seeks to illuminate the failing legal framework around femicide, and the artwork further works to interrogate intersections within a social memory that allows for the murder of women to be naturalized. Aqui Estamos is a call to action; in representing the mixed and myriad emotions that accompany the brutal treatment of those affected by femicide, it aims to re-dignify their memory, not only for their families, but for their communities.

YIARA MAGAZINE AQUI ESTAMOS 54

“i am safe inside this body”

POETRY

55

Spencer Allder

This body has a mind

Albeit a troubled, prevalent psyche.

Lips

Two advocates for my asylum

Shouting out

Standing up

Preaching the gospel of my safety, Teeth gnashing at my enemies, Hips swaying my divine pleasures.

Feet carry me

Spine rights me

Eyes shape my reality

Ears absorb sweet melodies

Lungs that breathe my ancient, sandy fires

Heart that beats my every desire.

Listen, Soft

What gentle herald my body holds, Fills my basket

Collecting memories

Like dandelions between my toes. Dip the bread of my pride in the swelling orchestra.

Cradle my sadness

Pry apart my sage, stiff blades of doubt

Seek my joy

Protect my worth; My body likes me, Loves me, My devotee:

I am safe inside this body.

56

FEATURE 57

JULIE GLICENSTAJN

Life changed for Julie Glicenstajn when she was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2017. Intensive and invasive surgery was followed by months of difficult recovery and physical rehabilitation, combined with a mixture of both fear and hope of what life might have to offer next for the then sixteen-year-old. The memories of this period are carried by Glicenstajn, both physically and emotionally. raw visualizes Glicenstajn’s movement toward catharsis, a movement of pain and healing, during an especially dark period of life. During the creation of this work, the artist has taken on the task of challenging hardened ideas of traditional feminine beauty, and having to navigate these questions through a world with very narrow definitions of womanhood.

Growing up in Brazil, Glicenstajn recounts living in a culture where women were relegated to exist within very traditional categories, leaving little room for those with expressions outside of the gender binary. After receiving an acceptance to art school two years after her surgery, she found herself wanting to investigate these ideas, especially in relation to her own body. She was further curious about the impact of asking such questions on her identity. In her art, Glicenstajn is interested in

challenging the idea that a woman can be narrowly defined by biology; the artist explores the moveable definitions of what it means to be a woman, and who is allowed to explicate or expunge those boundaries.

Glicenstajn decided to contribute to this conversation with her art. As a means to process her vulnerability and contribute to this conversation, Glicenstajn began the process of making this work by rolling red block printing ink onto her body and imprinting her physicality onto tracing paper and canvas. The red ink represents bloodshed, and the cotton materials represent the flesh being wounded and undergoing physical trauma. She then used these corporeal impressions to create a unique and striking composition along a long sheet of canvas. The work’s large scale enables its viewer to reckon with the enormity, fragility, and ultimate tenuousness of navigating physical trauma.

With raw, Glicenstajn links trauma and identity, body and expression, and reminds us that they do not exist separately from one another. What results from the artist’s investigations is an autobiographical representation of the body as a sort of shrine to the survival of the female self.

YIARA MAGAZINE VOLUME 11

58 raw

REVIVAL

ANDREA CHENIER

When nineteen-year-old Andrea Chenier left her small Ontarian hometown of Hawkesbury to pursue Studio Arts and Art History at Concordia University, she was determined to pay tribute to queer identities in her artwork. Chenier is self-taught, and initially, her practice involved the use of water colours and gouache. More recently, however, she has begun working primarily with oil paint.

Chenier’s move to Montreal was accompanied by an embracing of the artist’s queer identity, and a chance to finally place herself within the queer arts community. Since her arrival in Montreal, she has become more eager than ever before to portray the queer spectrum in her paintings. “It feels good to finally show that side of myself after not showing it for so long,” she said.

Her work Revival was born from these goals. Originally produced for an assignment with a “visual poetry” theme, the twenty-by-sixty-inch oil painting depicts the possibility of hope in connections between queer people. Whether that hope lies in undertones of romantic love, friendship, or just passing connections, Revival explores and provokes feelings of belonging and comfort. Two figures embrace, finding safety and joy in one another. One of the figures represents an allegorical depiction of spring, unencumbered and illuminated, wearing a spring dress and a serene expression. The other person wears wrinkly clothing, their face hidden from view.

In Revival, Chenier links the concept of hope to springtime. Her experience of moving from Hawkesbury to Montreal felt similar to a change of season—a light at the end of a dark tunnel, one where she could find solace and comfort among her own. Spring represents an opening and an untethering, a move into the sun—a similar process that a queer person may experience in moving from a small town to a city like Montreal.

Through her choice of colours, styles, and pose used, Revival spotlights the ongoing struggle for queer liberation and self-preservation throughout history, a story in which the presence of hope is necessary and vital. This trajectory has allowed artists like Chenier to seek refuge in representing their authentic selves—something that remains impossible for many around the world. Ultimately, it is hope that lies at the forefront of Revival; a message that queer love must be represented, never be taken for granted and whose power must be celebrated.

FEATURE 59

VOLUME 11

60

Revival, 20x60in, oil on canvas

GRAPHIC DESIGNER

FERNANDA ALVAREZ LARRAIN

COVER ARTIST

MARGRETHE NIELSEN

PHOTO PRODUCTION PHOTOGRAPHER

JANE EYRE JORDANS

Y/2023 61 YIARA MAGAZINE

VOLUME 11 62

VOLUME 11 Y/2023 YIARA MAGAZINE

Fig 1. Mélody à ses débuts, first self-published edition, 1985. Collection Nationale.

Fig 1. Mélody à ses débuts, first self-published edition, 1985. Collection Nationale.