6 minute read

TEACHING THE FUTURE BY LEARNING FROM THE PAST LIFE,

By Megan Crotty

The past is very much prologue for Randolph Community College Industrial Programs Department Head Wesley Moore. Whether it’s RCC’s Automation Engineering Technology or Electrical Systems Technology programs, Moore taps his decades of work in the private sector — as well as profound experiences throughout his life — to create opportunities and change the lives of RCC students.

Advertisement

Moore’s love of teaching — as well as his organizational skills, which helped his department navigate the COVID pandemic — earned him RCC’s 2022 Excellence in Teaching Award.

The industry bug bit Moore in the 1980s when he was taking computer programming classes at Sandhills Community College. One of the instructors teaching microcontrollers (now Programmable Logic Controllers or PLCs) in the electronics lab was having trouble with his computer and asked for help. Moore’s instructor turned the troubleshooting into a lesson for the class.

“When I went to that lab and saw a computer hooked up to machinery, and people using a mouse to make something start up — that intrigued me,” he said. “That was so much more fun than doing a formula.”

After re-starting his major and then graduating from Sandhills with a diploma in Industrial Electronics Technology, Moore plied his skills as everything from an electrical technician at Lucks Foods Inc. for 20 years to an automation manager at Carolina Dairy.

All the while, Moore was teaching Continuing Education classes at RCC when the College needed someone with experience with Mitsubishi technology.

“I’ve always enjoyed teaching,” he said. “The spark of learning, especially with somebody who’s interested in what you’re doing. At work, they’re interested in what you’re doing just so you get it done. The teaching is so much better than doing the actual work, especially when you've got a group that wants to learn.”

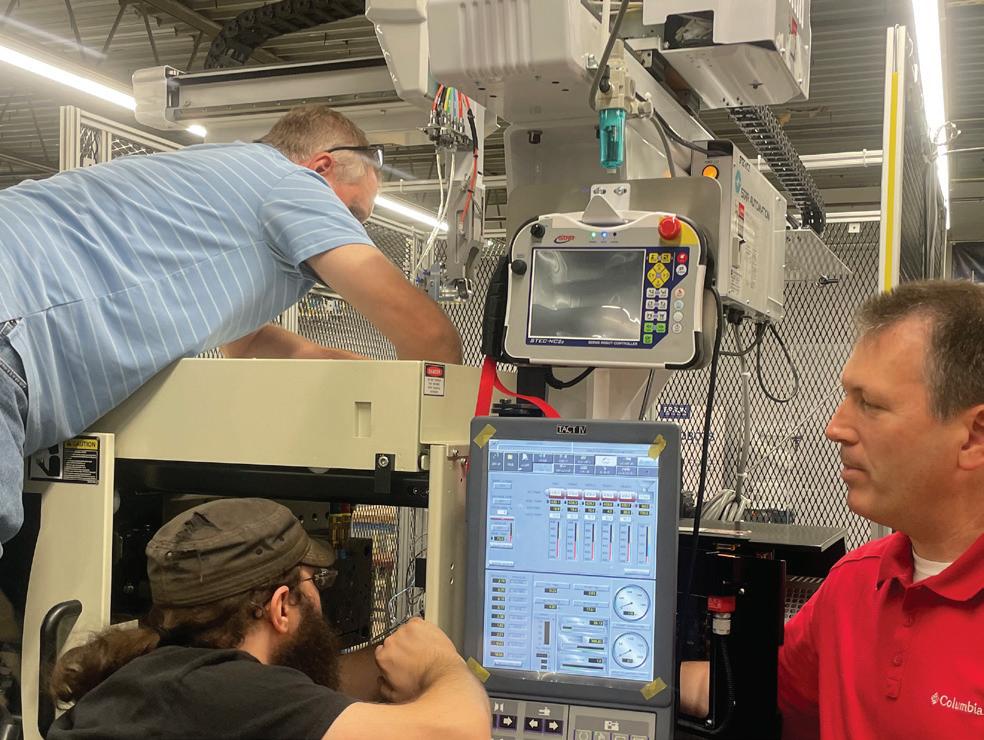

Industrial Programs Department

Head Wesley Moore, left, inspires students like Apprenticeship Randolph graduate Joshua DeFreece, who works for Post Consumer Brands.

In 2017, Moore became a permanent member of the Industrial Systems faculty, eventually being named Department Head in 2020.

A big part of Moore’s job is scheduling. With two, two-year programs plus Apprenticeship Randolph, which is a four-year program, he credits his “past life” in industry and computer programming with his ability to wade into the scheduling maze and come out organized on the other side with a plan.

Recently, Moore restructured the two programs under him — Electrical Systems Technology and Industrial Systems Technology (IST) — and changed IST to Automation Engineering Technology to be more in-line with what industries are demanding of their workforces.

For Moore, the change went beyond semantics — it means more RCC students will graduate with the skills needed for today’s — and tomorrow’s — jobs.

“We’re not trying to teach an engineer how to build an electric motor — that’s already done,” he said. “We’re teaching the technical skills needed to develop, install, calibrate, modify, and maintain automated machines.”

That includes instructions in computer systems, electronics, instrumentation, PLCs; electric, hydraulic, and pneumatic control systems; actuator and sensors, and process control robotics.

“There’s money to be made, and you can work in almost any industry — a modern sawmill, a manufacturing plant, a packaging facility, or a cake factory. That’s the beauty — there are no boundaries,” Moore said.

Graduates from the program will be prepared to work in industries that utilize control systems, computer hardware and software, electrical, mechanical, and electromechanical devices in their automated systems. The job opportunities include Maintenance Technician, Automation Technician, Automation Engineer, Engineering Specialist, Engineering Technician, and Reliability Technician.

The even better news? All the technology needed for the AET program is already at RCC, including Epson SCARA robots, cages and conveyors for the Advanced Manufacturing Center, and three FANUC mobile robots.

“Every ConEd class I’ve ever had — everybody who shows up wants to be there,” he said. “They’re trying to better themselves. When you teach curriculum, a lot of these kids are here, and they don’t know why they’re here. They may not understand what they got into because ‘Oh, that looks cool,’ and the commercials show robots. Well, that’s a robot working. We get to work on the ones that don’t work.”

In his PLC classroom with “a bunch of blinky lights,” Moore has gotten creative with showing his students how to program the machines to get the right sequence, including having students create a xylophone that plays a specific song.

“I try to give them visuals because some of them have a hard time with the blinky light thing,” he said. “We can’t actually close the clamp, inject the plastic, and turn on the cold water. We have to simulate it with lights. Once they see, ‘Oh, I can make this go back and forth,’ they can run anything.”

Moore tries to give his students realistic lessons for when they enter the workforce. “When I give you a project, the project might be graded on function, but it should matter to you that it looks great,” he said. “Would you buy a car that, when you opened the hood, looked like spaghetti?”

Through his many industry contacts, Moore is happy to help his students find jobs after they graduate. Of course, students never disappear completely for Moore, who has a “Box of Help” in his office. One student bought something he wasn’t sure how to use. Some come back and take a class for extra training after they’ve already landed a job. Another student was having trouble with a FANUC robot, and called Moore. After taking Moore’s advice on something to try, he sent his former instructor a video of the robot working along with a thumbs-up.

“That makes me feel good that he asked me,” Moore said. “I don’t know if he talked to the other engineers, but he didn't have to tell anybody that he talked to me. He came out looking like a hero.”

***

Away from school, Moore had a wake-up call in 2019. He and his wife, Tammy, were in a serious car accident the Saturday before Thanksgiving. Along with the physical scars, the crash had a profound impact on Moore. “It made me rethink a lot of things,” he said. “What really is important. I came to work with more energy. It affects you. I’m hoping for the better. Life is temporary. We need to take every opportunity we have. I look back at all the places I’ve worked. Nothing’s better than finishing well. So, I’m at the right place.”

Less than a year later, COVID hit RCC.

“It was pretty devastating for us,” Moore said. “There’s some things you still have to do that aren’t virtual. “Our programs are hands-on and we’re teaching skills — I can’t tell you virtually what it feels like when you turn the screw and you get to the end,” he continued. “That part was a real challenge. Traditionally, we weren’t really vested in Moodle. We didn’t have a lot of content because we’ve got these nice labs. We all scrambled together. Not only that, but I was still recovering from the accident. What kind of software can we use? What can we do? We learned a lot.”

Moore said that when students were able to get back in the labs, they appreciated the time more. “They realized it’s precious,” he said. “I had a student who was quarantined, and he was emailing me, ‘Is there anything I need to do for extra credit?’ He was afraid he was getting behind, which was a good thing.”

Moore also started embedding more videos on his Moodle page and got a camera that can film him as he instructs. One lesson in his Automation Engineering Technology students learn is that software is always changing, but in industry, whenever a machine is built and validated, to remain validated, the machine must keep the same components.

“The machines making the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines, there is somebody out there still has a laptop running Windows 7 to keep those machines running. You can’t just substitute parts because it may not perform the same.” To illustrate his point, Moore brought in a 20-year-old PLC from the former Luck’s Cannery. He plugged it in, and it still worked even though the plant has been offline since 2000.

“Industry works on a different model — if it’s not broke, don’t fix it,” he said. “As long as you’re vested in lifelong learning, this is for you because it’s always changing, but you can’t forget the past.”

Which is why, at Moore’s house, a Casio cordless phone from the 1990s still hangs on the wall. “It’s probably on the fifth or sixth set of batteries,” he said. “But it still works.”