7 minute read

Review: Generation X by Douglas Coupland

The end of the world, and hope, and hopelessness

By DESSA BAYROCK GENERATION X BY DOUGLAS COUPLAND

Advertisement

Douglas Coupland’s career begins with an eclipse: in the first three pages of Generation X, his first novel, the protagonist flies to Manitoba to witness the shadow of the moon snuffing out the sun.

“And in that field, when the appointed hour, minute, and second of the darkness came, I lay myself down on the ground surrounded by the tall pithy grain stalks and the faint sound of insects, and held my breath, there experiencing a mood that I have never really been able to shake completely — a mood of darkness and inevitability and fascination — a mood that surely must have been held by most young people since the dawn of time as they have crooked their necks, stared at the heavens, and watched their sky go out.”

This passage suspends time, place, and the concept of traditional generations; past and future blend together, and every young

it’s a story about three 20-somethings

who move to the desert to escape the strange, unnatural speed of large cities they live in a small town have unimportant jobs in the service sector and spend their days off sitting around in the sun telling each other stories in an attempt to batten down the fear that life has become too fast that things no longer make sense that some kind of apocalypse is forthcoming and that they will be powerless to stop it that they will be a part of it because all of humanity will be a part of it person becomes part of the same collective. This eclipse is chilling, unsettling, proof that even the most stable elements of the world — the sun, the sky — are subject to change, to subversion, to destruction. What other frameworks will these characters be forced to see evolve or disintegrate? I’ve been thinking a lot about Generation X lately, which is to say I’ve been thinking about a lot of things lately. I’ve been thinking about my own anxiety. I’ve been thinking about how everyone I know is tired. I’ve been thinking about how fast the world feels, how quickly time goes by, how quickly January slipped through my fingers.

I’ve been thinking about the fact that a weekend is a social construct, that we’ve been trained to think of Saturday and Sunday as icons of rest, and yet that more and more they feel like two more days of the week passing too quickly, cramming themselves too full. I’ve been thinking about deleting Twitter and Instagram from my phone. I can never quite bear to do it. But I’ve been thinking about it a lot.

And I’ve been thinking about Generation X. It’s a story about three 20-somethings who move to the desert to escape the strange, unnatural speed of large cities. They live in a small town, have unimportant jobs in the service sector, and spend their days off sitting around in the sun, telling each other stories in an attempt to batten down the fear that life has become too fast, that things no longer make sense, that some kind of apocalypse is forthcoming and that they will be powerless to stop it. That they will be a part of it, because all of humanity will be a part of it.

Humanity won’t just endure the apocalypse; humanity will be the apocalypse.

The apocalypse is this warped sense of time, this constant anxiety, this feeling that we’re all just insects beetling over the planet, crawling and eating and destroying and crawling and eating and destroying.

it’s a story about three 20-somethings

23 who move to the desert to escape the strange, unnatural speed of large cities they live in a small town have unimportant jobs in the service sector and spend their days off sitting around in the sun telling each other stories in an attempt to batten down the fear that life has become too fast that things no longer make sense that some kind of apocalypse is forthcoming and that they will be powerless to stop it that they will be a part of it because all of humanity will be a part of it So our heroes run to the desert, to the smallest, sleepiest, brightest town they can find. They find each other, there. And they tell each other stories, as though it will waylay the sense of impending doom they all share. As though it will waylay the impending doom itself.

I first read it when I was 16, and I hated it, because I felt invincible, because I thought the characters were too worried about nothing. I read it again at 19 and loved it, swore by it, carried it around like a safety blanket. I read it again when I was 22, when I wrote a Master’s thesis about it, about the apocalypse and its purpose in fiction, about Douglas Coupland and his fear of the future. This thesis was very dear to me, and it gave me nightmares, and it remains one of the most personal things I’ve ever written. Parts of that thesis have been repurposed here.

I’m afraid to read Generation X a fourth time, because I’m afraid I’ll start weeping and be unable to stop. So much has changed since it was published in 1991, and yet so little.

I’m trying to decide if I still believe that stories can save us. I’m trying to figure out if there’s anything we can do to stop the apocalypse, which seems more and more impending every day. I’m trying to decide what to do with my anxiety, with my endlessly scrolling Twitter feed, with the fact that time moves so quickly, now, that it seems unstoppable.

Which is, of course, because it is. I’m trying to figure out what to do with my own sense of helplessness. With the realization that the apocalypse isn’t the product of humanity but is humanity, all those people who vote for Trump and support pipelines through Indigenous territory no matter what the cost and don’t believe that the homeless or destitute or drug-addicted deserve compassion. People who see vulnerability as weakness. People who relish the relentless commodification and consumerism and capitalism

compassion I am trying to

build my life with care I carry books to a housebound friend I stand in the cold with 100 people and stop traffic of a million people beetling around the same city, crawling and eating and destroying.

For two full months in 2011, I seriously considered moving to the desert. I researched land costs and flora and fauna and bought a book called How to Build a Barn or Shed, which is where I intended to live. It’s hard to think about the future for too long before I begin to agree with the protagonists of Generation X, who seek brightness, and simplicity, and the kinds of fables they can tell one another as the sun goes down. But I never followed through.

in protest against the RCMP It’s not an option any more, to run away to a place where the apocalypse can’t touch you. The apocalypse touches everything.

invasion of Wet’suwet’en land I donate money to a science fiction magazine trying to reimagine and reqrite what feels like an And we have to do everything we can to beat it back from here, the land we stand on where we are, our current cities and landscapes and homes.

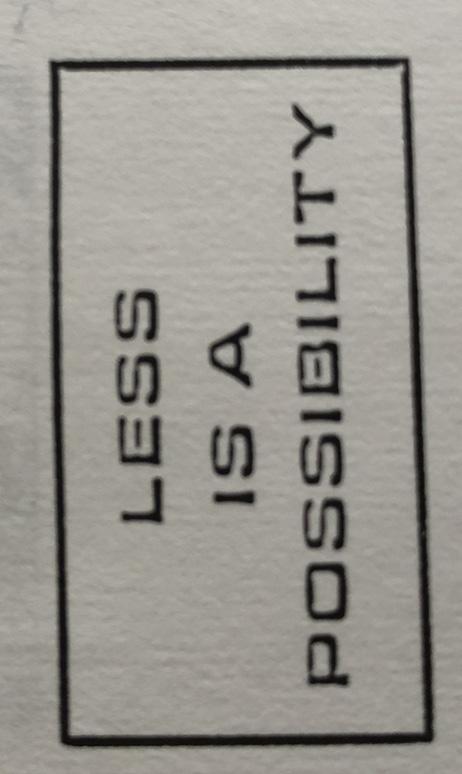

I am trying to act with compassion. I am trying to build my life with care. I carry books to a housebound friend; I stand in the cold with 100 people and stop traffic in protest against the RCMP invasion of Wet’suwet’en land; I donate money to a science fiction magazine trying to reimagine and rewrite what feels like an inevitable future, a terrible future, a capitalist future. I pull Generation X off my shelf and flip through it, remembering the way that Coupland filled the margins with anxious aphorisms. WE’RE ACTING LIKE INSECTS. NOSTALGIA IS A WEAPON. STOP HISTORY. I want to tattoo these aphorisms on my body. I can’t bear to reread it. Not yet. But soon.

I choose to believe that stories can save us. I choose to believe we will listen. When the time comes. When the apocalypse drifts over us like ash. STOP HISTORY. I hope we will.

inevitable future a terrible

24 future a capitalist future

call for submissions