Executive Editor

Janset An executive.beaver@lsesu.org

Managing Editor

Oona de Carvalho managing.beaver@lsesu.org

Flipside Editor

Emma Do editor. ipside@lsesu.org

Frontside Editor

Suchita epkanjana editor.beaver@lsesu.org

Multimedia Editor

Sylvain Chan multimedia.beaver@lsesu.org

News Editors

Melissa Limani

Saira Afzal

Features Editors

Liza Chernobay

Mahliqa Ali

Opinion Editors

Lucas Ngai

Aaina Saini

Review Editors

Arushi Aditi

William Goltz

Part B Editor

Jessica-May Cox

Social Editors

Sophia-Ines Klein

Jennifer Lau

Sport Editors

Skye Slatcher

Jo Weiss

Illustrations Heads

Francesca Corno

Paavas Bansal

Photography Heads

Celine Estebe

Ryan Lee

Podcast Editor

Laila Gauhar

Website Editor

Rebecca Stanton

Social Secretary

Sahana Rudra

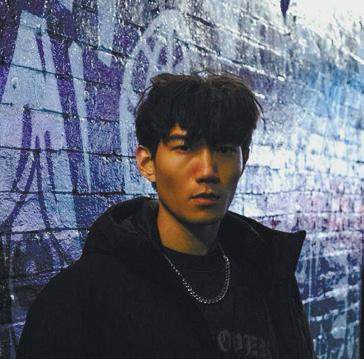

Suchita epkanjana Frontside Editor

Happy belated Valentine’s Day! In honour of this issue’s special Valentine’s theme, I have decided to make my rst solo editorial in e Beaver a riveting collection of love letter confessions to four romantic interests I’ve had since coming to LSE.

While these pursuits crashed and burned more embarassingly than my grades did in second year, at least they make for entertaining editorial content for you all to enjoy…

Dear J. A. ‘Turkish Delight’, You are like Turkish Delight, a dessert so uniquely enchanting it made Edmund Pevensie (from e Chronicles of Narnia) give up his entire family. I’m not saying I would do the same thing, but…

I rst met you at the hustings for e Beaver, when we were

By Lovestruck Beaver

running for the same position. I admit, I was intimidated by how serious and mature you looked whenever you stood up and talked about how you would deal with ethical crises. I’m glad we both ended up getting positions at e Beaver anyway, because now I get to see you at every meeting with that same intense look in your kohl-lined eyes when you say, “Guys, let’s focus on making this issue the greatest one ever.”

I really think we would have been a great ‘rivals-to-lovers’ story, except the ‘lovers’ part never actually happened.

Dear O. d. C. ‘Crème Brûlée’, Like crème brûlée, you are the epitome of delicate European sophistication. I’ve forgotten how we met the rst time, but I vividly remember your dusty blonde waves, dimples, and blue-green eyes like the

Mediterranean sea glinting under the summer sun.

You don’t speak much, so I eagerly await to hear your so voice when you announce how broke e Beaver is this term, or how many copyediting mistakes I’ve made in my articles.

I know you’re graduating this year, but before then, I’d love to have deep conversations with you while drinking co ee from your Moomin mug collection.

I could only hope you paid less attention to (married) actors and more to your secret admirer who was right here all along.

Dear S. C. ‘Pineapple Bun’, e yellow streaks in your hair are like the sweet sugar crust on this classic Hong Kong dessert. Your chirpy voice and energeticness remind me of the vibrant, chaotic comforts of home and of adventure, all at the same time. Every day, you draw and paint other people for hours, but in my opinion, you deserve to be the artwork itself.

It’s too bad you have a boyfriend though.

Dear E. D. ‘Strawberry Shortcake’, You are subtly sweet and lighthearted, with pockets of sour punchiness in between. Although you are graduating as well, I will probably never forget your curly, strawberryred hair and your wonderfully short stature. Nor will I ever forget our outings to Sontag for Yuzu soda on dreary Monday evenings, during which I listened to you drone endlessly on about your love for omas Brodie-Sangster.

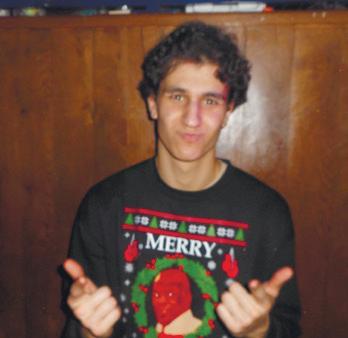

Paavas Bansal Illustrations Head

Any opinions expressed herein are those of their respective authors and not necessarily those of the LSE Students’ Union or Beaver Editorial Sta e Beaver is issued under a Creative Commons license. Attribution necessary. Printed at Ili e Print, Cambridge.

2.02

Voice your concerns or praises for your department’s

Saira Afzal

News Editor

Photographed by Ryan Lee

On 5-7 February, LSESU’s Chinese Students and Scholars Association (CSSA) organised a Chinese New Year market in the Centre Building Plaza, welcoming in the holiday with activities, games, and traditional snacks.

Students enjoyed festival games like pitch-pot, ring toss, and lantern riddles for prizes, all traditionally associated with good luck. e market hosted a plethora of DIY workshops, including lacquer fan-making, calligraphy, stone rubbing, and lantern making.

e calligraphy workshop involved writing Chinese phrases like “Happy New Year” and “Good Fortune” on red paper, which are then hung up on doors to bring wealth and prosperity.

Most popular was the stone rubbing DIY workshop, showcasing a 1,500 year old technique used to create inscriptions. e process involves placing a sheet of paper over stone and inking over it, to recreate Chinese art or texts. is method has long been a part of China’s artistic and cultural history, so it’s no wonder the workshop was constantly busy!

Students could also create or purchase beautiful beaded jewelry, embroidery art and cultural gi s from the stands. Traditional Chinese snacks and gi bags were also available, adorned with intricate traditional designs, with the gi bags containing natural Chinese medicines believed to bring good fortune.

We asked students what Chinese New Year meant to them, and how they typically choose to celebrate. Catherine, a BSc Economics student and a CSSA member, said Chinese New Year meant a “day of

gathering for families”, which she considers a special time as it is di cult for everyone to gather together at other times in the year.

Catherine’s favourite dish to eat on Chinese New Year is dumplings, because she brings together her friends and family to make them as a team. Everyone has a di erent role; some are in charge of lling the dumplings or closing the outside so they can be cooked, turning the creation of a traditional dish into a fun bonding experience. Catherine’s favourite activity on Chinese New Year is to receive red envelopes from her family, as it’s the one chance to receive lots of money from loved ones!

Jessica-May Cox, a BSc Sociology student, told us that Chinese New Year is a “time of joy in a dark and depressing winter”. Her favourite dish to eat during the holiday is lamb hotpot from Haidilao, and her favourite activity is to watch the dragon dance in Chinatown.

Lucas Ngai, a BA History student, said Chinese New Year was always a “chill way to get together with family”, and that he looked forward to seeing his cousins during the holiday. One of Lucas’ core memories is playing Wii Sports at his relative’s place with his cousins, which became an at-home tradition for his family.

Emma Do, who celebrates Lunar New Year, told us that the holiday for her simply means

“home”. Emma’s favourite dish to eat during the holiday is chung cake, a traditional Vietnamese cake usually made from rice cake, mung beans, and pork belly.

Learn more about the market on Instagram using this QR code, in collaboration with LooSE TV.

Ann Vu Staff Writer

On 31 January, Smriti Irani, a former Indian Cabinet Minister, was invited to speak at the LSE Old eatre in a reside chat hosted by the LSESU India Society in partnership with the Indian National Students Association (INSA-UK). Around 100 students attended the event, which covered topics of women’s empowerment, challenges and prospects of AI and digital transformation, and re ections on Irani’s own career.

Irani served as a Cabinet Minister from 2014 to 2024, holding o ce for various roles including Women and Child Development; Minority A airs;

Information and Broadcasting; Textiles; and Education. Prior to her political career, she gained wide recognition for her role in the TV series Kyunki Saas Bhi Kabhi Bahu i (2000-2008).

e rst section of the reside chat was moderated by INSA-UK’s President Amit Tiwari and LSE Professor Alnoor Bhimani. During the section, Irani stressed the need for greater nancial investment in women-owned businesses as a priority in India’s e orts towards gender equity. “ ere is always money for a good cause but that money runs out. But money never runs out for money,” she said.

On women’s empowerment in relation to the digital transformation, Irani encouraged looking at AI from the per-

spective of its impact on women’s agency, rather than solely through a lens of computing and automation. She highlighted both the potential it holds for recognising women’s importance in the workforce, as well as its threat to women’s employment speci cally, and the labour market more generally, with a projected 70% of jobs held by women “vanishing” due to automation.

“ ere is a need for deeper partnerships between men and women and other genders across the world. We either swim together or sink in parts,” she added.

Regarding India’s position in this global digital transformation, and its initiatives to provide access to technology and the internet, Irani insisted, “I don’t think India is at such a

crossroads right now of human history where we need to sit in the shadows of the West.”

She emphasised India’s role as the “home to global engineering” and “global CEOs”, and its potential as a “destination for global innovation”.

e second section took a tonal shi , as Irani discussed her identity and her former acting career in conversation with Anuj Radia, an entertainment independent journalist, and Joseph Parel, the LSESU India Society President.

On her identity, she said, “Every facet of my life – minister, mother, actor, activist – it is just a part of my whole journey.”

She appreciated the human impact of her on-screen presence in moments where others

came to her with their vulnerabilities. However, a challenge she identi ed in her acting career was that her on-screen persona sometimes overpowered her personhood, obscuring her internal struggles.

In her nal words to Indian students studying abroad and wanting to make a di erence to their country, Irani suggested looking at inputs that their local area needs speci c to their area of expertise, to better their systems.

“I think we all presume that service is something that we do either in a constitutional position or a bureaucratic one, but if you can help one fellow Indian, that’s service to your country.”

Amy O’Donoghue Staff Writer Photographed by Ryan Lee

LSE hosted an informational session on its Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Policy, regarding its investment activity. is comes a er intense pressure from students during the 23/24 academic year for LSE to divest from harmful industries,

culminating in LSESU Palestine Society’s ‘Assets in Apartheid’ report, as well as the SU referendum in which 89% of respondents voted to divest from fossil fuels and weapons.

e session was led by Mike Ferguson, LSE’s Chief Financial O cer, and Caroline Butler, the Senior Independent Adviser on ESG policy.

During the session, Ferguson

and Butler discussed the policy approach towards LSE’s investments, which amounted to £545,7 million at the end of 2024.

Butler emphasised sustainability, claiming there is a regrettably low pro le of recognition for how much LSE has done for climate change. She highlighted that they have invested £270 million on energy ecient buildings since 2017, and raised £175 million in green bonds.

In November 2022, LSE committed to a new ESG strategy, which attempted to “minimise investment exposure” to companies pro ting from thermal coal, tar sands, tobacco manufacturing, and indiscriminate weapons manufacturing.

When questioned about LSE’s motivations for divestment

from the tobacco industry, Butler responded that the decision was solely based on the nancial risks associated with continuing to invest in this industry.

Questions were also raised about whether the investment guidelines adequately consider concerns for human rights. One audience member pointed out that human rights were scarcely mentioned in the university’s written ESG policy.

Another asked whether further action would be taken to make investment policy more ethically compatible, in line with the ndings of the 2024 ‘Assets in Apartheid’ report.

Butler responded that ethics were an “impossible question” in investment. Another audience member probed further, questioning the panel on whether they were fully considering the risk of their investments potentially tied up in human rights violations further down the supply chain. Butler stated there was no concern because LSE’s investments were fully in line with British law.

ere are further ESG discussion sessions scheduled throughout the year, so students will have more opportunities to confer with administrators on how LSE investment policy works and how it could be improved in the future.

e report, which was produced by a collaboration of LSESU societies, claimed that LSE invested into companies pro ting from mass human rights violations in Gaza, such as Toyota and BAE Systems.

Suchita Thepkanjana Frontside Editor

Photographed by LSESU Think Tank Soc

On 6 February at 6pm in the Centre Building, two-time North Korean defector Timothy Cho spoke about his life, his escape, and his political activism at the LSESU ink Tank event entitled ‘From Oppression to Advocacy: Timothy Cho’s Story’.

e event started with an introduction of Cho by an LSESU ink Tank representative, who highlighted Cho’s position as the Secretariat to the UK All-Party Parliamentary Group on North Korea and his multiple speeches at the UN Human Rights Council.

Cho began his speech with a satellite photo of the Korean peninsula, depicting North Korea as almost completely dark. He declared, “I’m not telling you political theory today—it’s only my life…and what I saw.”

Cho described his experiences growing up in North Korea, which he calls a “Hermit Kingdom”. He likened North Korea to e Hunger Games, separated into districts with supervisors responsible for surveilling civilians. He recalled bowing to portraits of the Kim family every morning, having “self-criticism sessions” starting in primary school, and watching public executions from the front row.

When he was nine years old, his parents escaped North Korea, leaving him orphaned and branded as a member of the “traitor class”. Because of this, Cho was rejected from schooling, jobs, and even the military, which eventually drove him to escape the country himself.

He explained, “ is country, that I believed was the best in the world, now abandoned me.”

Cho described his two at-

tempts at escaping North Korea. e rst time, he was arrested by the Chinese military and deported back to North Korea, where he was imprisoned and interrogated, before being released into his grandparents’ custody. He decided to escape once again and ended up imprisoned in Shanghai.

He was sent to the Philippines as part of an international movement to free him and other North Korean defectors. Finally, Cho arrived in the UK, where he gradually learned English from lessons and volunteering in a soup kitchen.

Cho ended by re ecting on all the people who looked a er him on his journey out of North Korea, including fellow

orphaned children, the prison inmates, and his grandmother who helped him escape.

“Sometimes the survivor’s guilt is really, really haunting … from time to time, I still see them in my dreams,” he explained. “It’s the acts of love and acts of humanity that gave me hope. It’s the hope from when we rely on each other in

the darkest moments.”

Cho concluded the event by reiterating the importance of humanity and empathy. He urged the audience to “remember your responsibility and use the gi in your heart.” “In the world, there is a lack of love,” he said. “But it’s not nuclear weapons that control the world—it’s heart.”

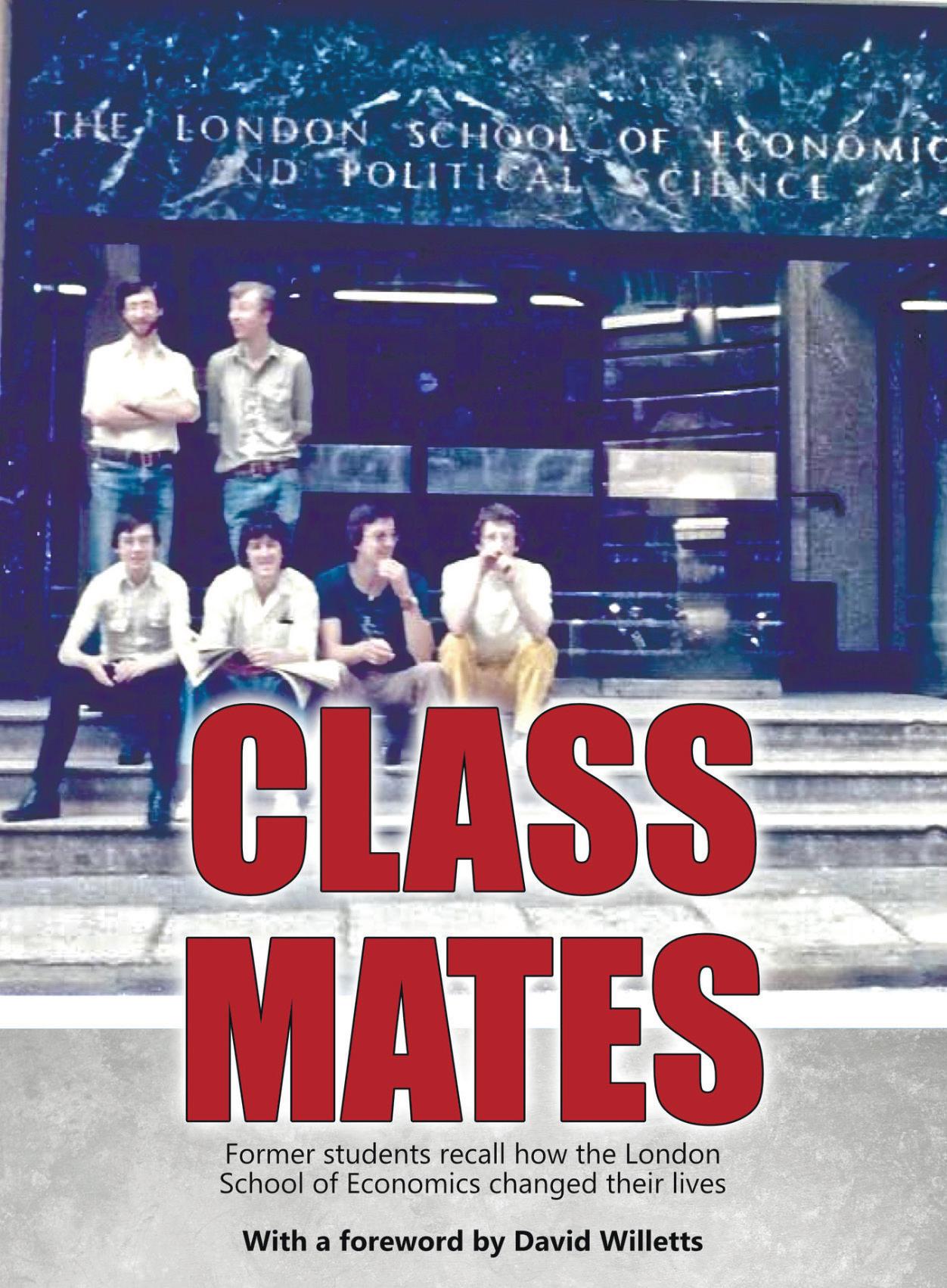

Cameron Baillie Alumnus

Senior faculty and sta have written to LSE’s Council Chair and School Secretary expressing “deep dismay” regarding a senior Council member’s public aggression towards peaceful pro-Palestinian protesters.

A letter signed by two-dozen members of LSE’s community on 20 December 2024, since shared with e Beaver, accuses School Council member Stuart Roden of “troubling” conduct and language, and violating multiple behavioural responsibilities.

Roden is video-recorded “screaming as he points repeatedly and aggressively at demonstrators” outside the Labour Party’s conference in October 2023 and exhibits “highly belligerent body language as he engages the demonstrators”, the letter alleges.

e signatories request an “investigation into whether Roden’s conduct meets the standards for ethical conduct expected by the School” and an assessment of Roden’s tness “to serve as a Council member and member of the Finance and Estates Committee”.

e signatories from eight di erent departments accuse Roden of violating LSE’s ethics code, bringing “the School into disrepute”, and breaching purported norms of “institutional neutrality”.

ey further claim that Roden’s behaviour, alongside his senior position within School governance, “raises important questions in relation to the rationales Council and SMC gave for their decision not to divest from entities implicated in international law and gross human rights violations in the Occupied Palestinian Territories earlier this year”.

is references Council’s decision on 25 June 2024 to deny widespread demands that LSE divest its reported £89 million from companies complicit in crimes against Palestinians, as well as those involved in nancing arms and fossil-fuel industries.

Calls came from current students, sta and faculty, Jewish members of LSE’s community, and School alumni, consolidated by last year’s record-turnout student referendum in which 89% of LSE students voted for divestment.

Signatories doubt Roden’s

ability “to ful l his duties impartially … in light of his very public positioning on this highly sensitive question”.

ey also question Roden’s role in ongoing ESG Policy revisions concerning School investments following his public display of partiality.

Alongside positions within LSE, Roden is founding chairman of Hetz Ventures, a venture capital fund for Israeli tech startups, joint-founded by active Israeli special-forces soldier Judah Taub and top Cameron-era Conservative peer and ex-Party Chairman Lord Feldman. Other Hetz leadership team members also served in elite Israeli military-intelligence units.

e letter summarises that Roden accused demonstrators of murder; accused them of celebrating murdered civilians; equated calls for Palestinian liberation with antisemitism; goaded protesters into attacking him; and sought to impede protestors from exercising their rights to freedom of speech and of assembly.

Roden was recorded shouting “attack me like you attacked them”, “you’re murdering people”, and “you came into a country, you murdered chil-

dren” at the peaceful demonstrators, alongside calling various assembled people “disgusting”, “cowards”, and “stupid”. e video has been viewed over 127,700 times on Times Radio’s YouTube channel.

e letter questions whether Roden, in his public outburst, treated “others with respect and dignity”, displayed “tolerance of di erent viewpoints”, behaved inclusively, or respected “the right of others to express and protest freely”. is is particularly challenging for LSE’s Council, given that as “a School governor, director, and trustee, Mr. Roden is in a position of high public visibility”.

e signatories express that Roden is “entrusted to represent the School. We ask whether his behaviour is a breach of that trust and whether it damages the School’s reputation while he remains a Council member.”

One signatory shared that “concerned sta await Council’s action against unacceptable conduct from this senior member of the School community”– like that taken swily against the LSE_7, since acquitted – “unless it will instead seek to defend Roden’s behaviour”.

Roden did not respond to a request for a statement as of the publication date.

An LSE spokesperson said:

“Last month LSE received a letter from a group of faculty regarding an encounter which took place on 9 October 2023 outside the Labour Party Conference, involving a member of the LSE Council and a group of protestors. We have looked into the incident. While it is a highly charged exchange, we do not believe any action is warranted.”

“ e incident, a one-o event, occurred two days a er the

October 7 attack. Feelings were running high, and reactions in the moment were even more charged than usual on all sides. As we have tried to make clear, outside the classroom, the LSE Ethics Code and School’s Statement on Committee Effective Behaviour do not regulate lawful speech, even if it is controversial or may pose a reputational risk. at is the case for this exchange, as it was when we received complaints about speech from LSE faculty immediately a er October 7.”

“Freedom of speech, including the right to protest, are of the utmost importance to LSE. Our free speech policy is designed to protect and promote peaceful freedom of expression on campus.”

“ e LSE Council decisions relating to divestment last summer were reached by unanimous consensus in both the Finance and Estates Committee and in Council, which included faculty, student, and sta members. Council’s reason for its decision was that the School, as such, should not take positions on controversial geopolitical con icts, including in its investment decisions. is conclusion applies to any and all such con icts, and for that reason was not driven by the views of any Council members on this or any other particular controversy.”

Regarding investments, the spokesperson commented:

“LSE is committed to strengthening our approach to responsible investment in line with our Environmental, Social and Governance Policy, Following recent discussions within the LSE community, a review of the policy consistent with Council’s decisions from last summer is currently underway.”

Read the full article online.

‘Elections

features.beaver@lsesu.org

Angelika Santaniello Staff Writer

Photographed by Ryan Lee

With approximately 1.5 billion people voting in 2024, and the world now beginning to experience the implications of this ‘year of elections’, it seems impossible to avoid discussing the nature of elections and the future of democracy. Yet, generating an educational environment for these conversations can be challenging, particularly as many citizens attempt to reconcile empirical evidence with media headlines and their own opinions on the state of democracy. is is foregrounded in a university environment, as an attempt to unpack the ‘year of elections’ involves an interplay between the voices of academics and, crucially, students.

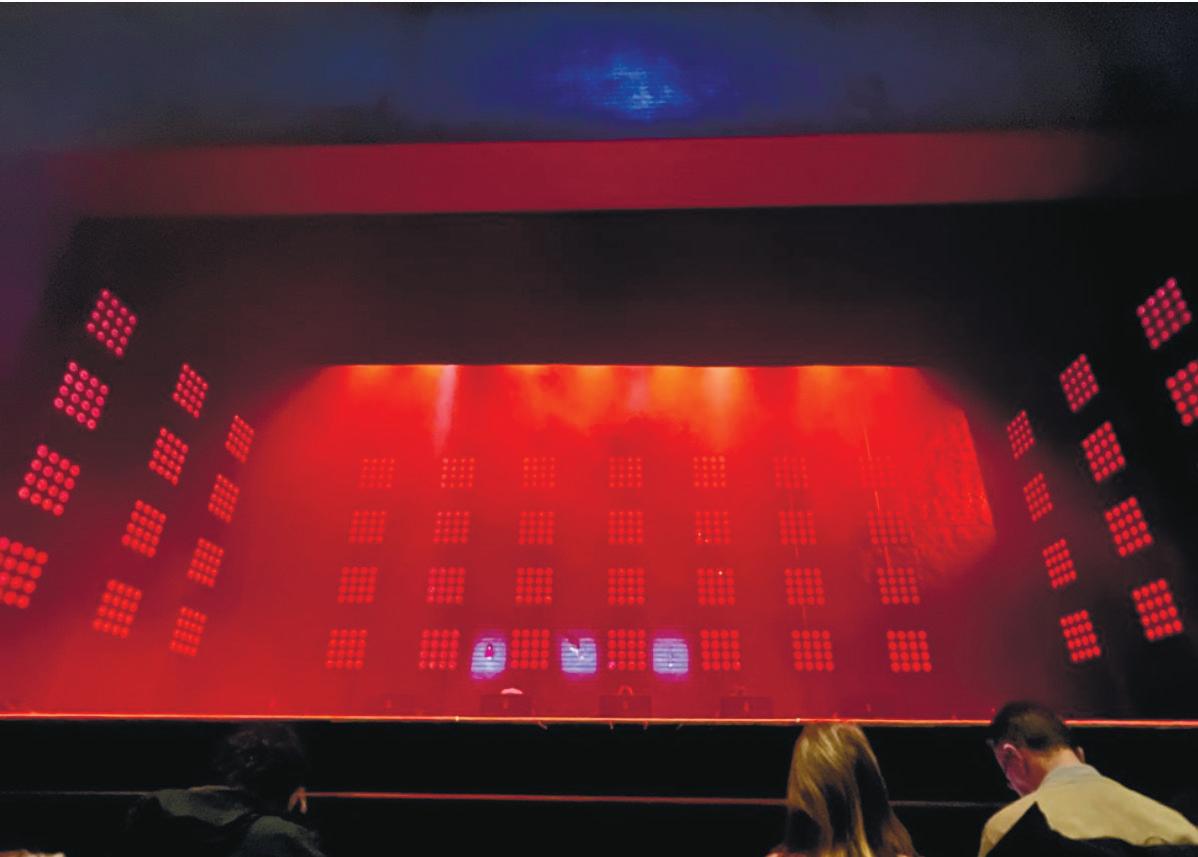

‘ e State of Democracy After a Year of Elections’ public panel, held in December 2024, was the culminating event of the LSE Global Politics series, channeling textured analytical commentary from LSE academics. Scattered among the 400 seats of the Sheikh Zayed eatre were LSE alumni, students, external academics, and sixth-form students.

I found myself sitting between an A-Level student interested in politics, and an LSE alum, who had been following the research project. e panel was clearly designed to encourage political dialogue across generations; however, the proportionally limited number of LSE students who actually engaged in the discussion throughout the evening led me to question how well the external academic perspective on elections reects student opinions.

e speakers each alluded to the growing importance of the ‘young voter’. For instance, Professor of Social Anthropol-

ogy and inaugural director of LSE’s South Asia Centre, Mukulika Banerjee, emphasised that the 2024 Bangladeshi General Election “was dominated by students”.

Professor Sara Hobolt, Professor of Geography at LSE and Sutherland Chair in European Institutions, noted that challenges to political institutions have in part re ected a reality that “Young people are much more likely not to be supportive of liberal democratic institutions, [which is] concerning when you have that in conjunction with political leaders who clearly don’t have these strong norms.”

Qualifying discussions on young people, an A-Level Politics student, Jess, asked about the correlation between the rise of technology, social media, and right-wing populism. Responding, Professor Banerjee articulated “there is a whole political economy and industry of [those] who are creating a genre of music whose lyrics are as hateful as one can imagine— this plays at weddings, political rallies, demonstrations so it's in [everyone’s] subliminal subconsciousness.”

“It’s not just the trolls on social media and misinformation. It's the actual pushing through [of] aesthetics that appeals to people. at is the real danger.” Hence, greater attention must be paid to educating young voters, who drive an online political presence, in detecting online propaganda and misin-

formation.

is reveals that the student-voter perspective is becoming increasingly pivotal in shaping electoral campaigns and outcomes, yet continues to be largely omitted from political analyses. Understanding the bres of a ‘year of elections’ therefore requires active participation in political conversations.

A few weeks into the Winter Term, I asked LSE students to dwell on the changing political stage. Initially, a few expressed discomfort in discussing politics-related matters. Perhaps their reluctance alludes to a pervading in uence of detachment from global political issues, or individuals feeling insu ciently politically informed about certain matters, all inhibiting factors to productive educational discussions.

A Politics and IR student, Ethan, focused on unilateral military action, observing that “political attitudes toward conict and risk, particularly to civilians, [haven’t] really changed. is shows no sign of changing unless we advocate for a more informed and aware electorate.”

Victor, an IR student, proposed an alternative perspective: “I wouldn’t say international issues have in uenced my outlook on domestic politics at rst glance because I have always seen them as critically important [but] fundamentally [global political issues force] you to understand that politics is diverse and nothing is imper-

meable to the world.”

He added, “You can’t act like an ostrich and pretend the sand of international issues doesn’t affect you.” In other words, it is critically important to discuss politics in everyday conversations to digest the complex facets of a rapidly changing political scene.

Nour, a Law student, o ered

Addressing the direct implications of the ‘year of elections’ on LSE students, Michelle, a second-year Law undergraduate, emphasised the role of university-provided resources in “fostering active youth citizenship.”

“[Public lectures and research hubs] encourage LSE students to engage in informed debates. [ is shows] that active youth

‘Active youth participation is crucial for ensuring that democratic decisions re ect the interests and needs of all generations.’

a more introspective lens: “Growing up in the Arab world, I’ve always been aware of how outsiders perceive us. Seeing how the media and politicians in the West reduce us to conict and extremism has shaped the way I think about politics— not just in terms of how my own country is governed, but also how global power structures control narratives.” is emphasises the importance of humanising an analysis of elections, democracy, and politics through ordinary discourse.

Farah, a Law and Anthropology student, built on this. “ e likelihood that someone is from a country that had an election this year is so high,” she stressed, asserting the bene t of focusing on “countries that are less hegemonically powerful or even less studied in international relations and politics. eir elections were overshadowed by the UK, US, [and] Indian elections.”

Nour elaborated on the above, sharing that “elections aren’t just about who wins and loses: they shape how entire regions and peoples are perceived.” is foregrounds the importance of framing a discussion on elections around the issues posed by problematic rhetoric, countering dangerous narratives with ordinary conversations, not only by processing academic perspectives.

participation is crucial for ensuring that democratic decisions re ect the interests and needs of all generations,” she said. is arguably indicates a need to contextualise political discussions within the student experience.

However, Aiza, an IR and Chinese student, points to more damaging implications for the community: “For our generation, most of whom have lived our entire lives in uncertainty and anxiety around global politics, I think 2025 will be very hard mentally for a lot of people. I think now more than ever the community needs to look out for each other.”

Re ecting upon student views, there is a need to exceed detached academic analyses of elections. ey revealed the importance of everyday debates in processing the personal – and communal – nuanced implications of the rapidly changing global political scene in 2024.

As Ethan remarked, “making our goal to ‘know the causes of things’ [is] ever more important for us.” Certainly, 2024 cannot be marked as ‘the year of elections’ if one avoids addressing all facets of elections, and if the views of the increasingly important student demographic are undermined or omitted from discussions on democracy.

Mahliqa Ali Features Editor

Photographed by Ryan Lee

The academic pressures of LSE can o en feel as though between lectures, deadlines, and latenight library sessions, there is not enough time to engage in hobbies or extracurricular activities. Nevertheless, many students carve out pockets of time outside their studies to pursue hobbies, whether to destress, upskill, or connect with people. Ultimately, university is not only about degree-related intellectual growth but also creative exploration, socialising, and personal development. How are LSE students making use of this unique environment where you can try almost anything?

Liza, a third-year Social Anthropology student, took up commercial dance through LSESU’s Dance Society. “I’ve wanted to learn how to be good at dancing for many years, but I never felt comfortable enough to try. In my nal year, I decided it’s now or never. e classes o ered such an easy opportunity - student-friendly prices, insanely good quality teaching, and conveniently located right on campus,’’ she says.

“LSE is a very intense academic institution, a lot is expected of us and we expect a lot from ourselves. Everyone is working so hard and a lot of people are grinding, grinding, grinding in the library all day. I personally can’t see myself doing it that way. I need breaks, I need to move. I’m a strong advocate for not grinding yourself into the ground. Doing things like dance have helped me achieve that balance,’’ observes Liza.

Momina, a third-year Law student, has tried many extracurricular activities, both at LSE and beyond. She joined the university-based Cra s Society and Mahjong, and tried ceramics and padel o -campus.

“I think a lot of us, especially at LSE, feel really guilty when

we take time o . I don’t know what it is, but it’s so universal. I think accepting that it’s ne to not be working all the time is a major part of it,’’ she adds.

Both Liza and Momina highlight aspects of self-development their hobbies nurture which are not necessarily linked to their degrees. Liza explains, “I’ve become much more liberated, free, and condent in myself and my body. Doing an activity once a week which has nothing to do with my career or education is pure joy. It’s showed me how important it is to do things which energise you from within and bring you pleasure.’’

Liza adds that LSE students tend to pressurise themselves to always excel academically, in a way that extends to all other areas of life. In this light, trying new things can significantly help with developing the habit of positive self-talk.

Liza recalls that during her rst dance class, she “tried to be as non-judgmental [towards herself] as possible. I told myself I’m doing this for myself, I’m learning, I may not get it right the rst time but that’s okay because I’m here to have fun.’’

While hobbies can o er a respite from the world of academia and careers, they also

hobbies don’t really relate.’’

“I think from a mental wellbeing perspective this is a good thing because I’m keeping that sort of strict divide between what I enjoy and what I would be doing for work. But you can also discover what you might like to do as a career through hobbies.’’

"For example, I always ruled out doing something creative, but I’ve been going to art exhibitions and art auction houses like Sotheby’s and Christie’s since rst year. It was through these that I realised this is a whole industry of careers I could venture into. At LSE, it’s easy to pigeonhole yourself into limited careers like nance, consultancy, law, but we forget there’s so much more out there,’’ she re ects.

Ryan, a General Course student and Photography Editor at e Beaver, got into photography when his dad gave him an old lm camera in 2021. He continued nurturing his passion at his home university, Georgetown, taking a photography module and taking pictures for their paper.

“I still don’t know what my career direction is, but if I got a job o er from somewhere like National Geographic, I would totally do it. I study Politics,

‘I’m a strong advocate for not grinding yourself into the ground. Doing things like dance have helped me achievet that balance,’ observes Liza.

o er an opportunity to explore what you might like to do in the future, especially if you would like to explore creative industries while studying at a highly corporate, career-oriented university.

Momina acknowledges that her hobbies do not technically relate to her career as a law student, but have broadened her perspective. ‘’I don’t know exactly what I’m going to do, but if I were to go into a corporate commercial law job, then these

makes it easier because it’s like a friend I can take with me.’’

Despite the many social, upskilling, and leisure bene ts to hobbies, hobbies aren’t always accessible due to nancial and time constraints. Liza appreciates that “the Dance Society membership is very accessible compared to how much you’d generally have to pay for dance classes in London. A yearly membership is around £30, and each class credit comes out to around £5.''

Momina also praises the accessibility, comparing her on-campus hobbies to those o -campus. She notes that Cra s Society, which she joined for crochet lessons, has cheap membership which includes supplies and teaching.

the photography course I had to do coursework for. Contrastingly, there aren’t any photography modules at LSE and I don’t believe you can rent out cameras from the library. e LSESU Photography Club is defunct at the moment.”

He adds, “LSE is a very economics and political science focused university, so it makes sense there aren’t creative departments. It’s understandable from an institutional perspective, but from a hobbies standpoint, those are de nitely restrictions. e nancial cost is a barrier as well, cameras can be hugely expensive.’’

and the only point where it would overlap is photojournalism or if I wanted to photograph congress or parliament, but I don’t see myself going in that direction,’’ he says.

For Ryan, the bene ts of photography are largely unrelated to his career aims. “Photography gets my mind o things. Most of what I do is just walking around and taking pictures. I’m an introvert at heart, so I tend to feel awkward when I’m alone. Having a camera

Comparatively, her experience of playing padel outside LSE revealed how much campus societies facilitate pursuing an activity. “ ere’s a huge bene t to trying things through societies because most memberships are a standard price of £1.50 to £4, and the events a er that are mainly free. Playing padel was really expensive because I had to buy the equipment myself, and I had to travel far to access the courts.’’

Ryan noted that “there is a lot of constraint on getting involved with photography, especially at LSE. At my home institution, I could rent out cameras from the library, which I did because there was

Despite this, Ryan recommends not letting the nancial cost deter people from trying photography. “ ere are plenty of entry level cameras that are pretty good and not too expensive.’’

e range of hobbies o ered by LSESU societies provides students with a unique opportunity to try almost anything, in a generally a ordable, low-stakes and light-hearted environment.

In Liza’s words, “We’re only here for three years, and time really ies. Although student life is so busy, ultimately it’s our late teens and early twenties when we are supposedly most energetic, and it’s a very good opportunity to try new things.’’

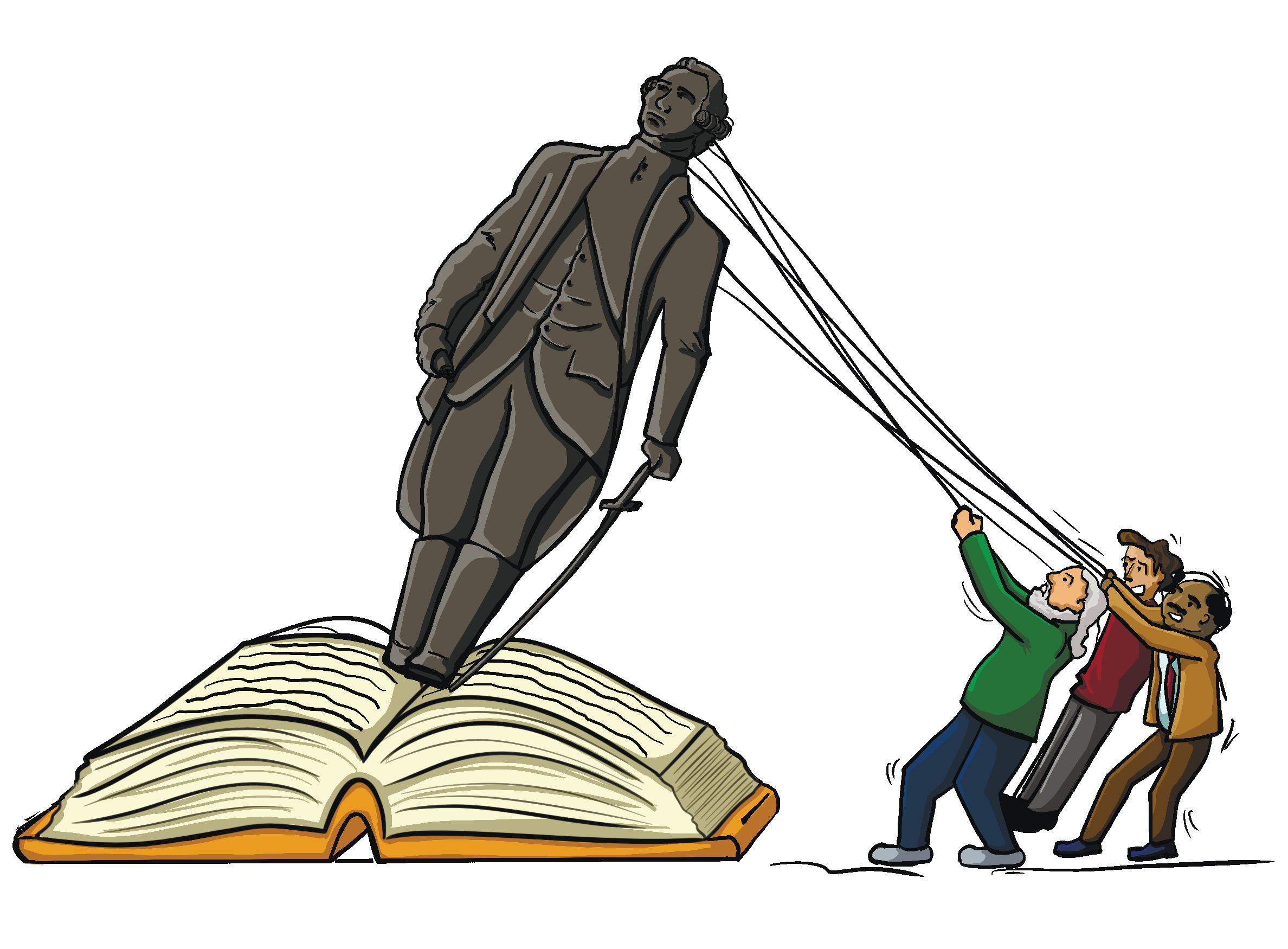

Arushi Aditi Review Editor Illustrated by Paavas Bansal

The global Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement facilitated increased advocacy for more diversity and inclusion in all elds, including academic institutions. Inspired by the BLM discourse, students demanded ameliorated inclusivity of all races, genders, and ethnicities – especially minorities –in terms of research, teaching content and educational materials provided by the institutions.

While diversifying research applies to subject matter, voices, methodologies, and examples used in academic teaching, decolonisation also encompasses the epistemological foundations upon which we build intellectual theories. It is crucial that we tackle the multifaceted and intricate nature of decolonisation at international institutions like LSE, which can set a positive example of inclusivity on a global platform.

Decolonisation in Social

At LSE, the conversation has been sparked through reports such as “Decolonising Social Policy: A First Step,” written by sta members and students of the university’s Social Policy department (one of the more vocal departments when it comes to studying the Global South). is project took place during the COVID-19 pandemic to ensure the integral inclusion of student perspectives, and highlights both the positive aspects and the ethnic, gendered, and racial disparities within LSE’s Social Policy research.

One professor who contributed to the study stated that several students did not feel that their voices were represented in the so-called “international” course, referring to lecture content, authors studied, and ideas more broadly. e students’ concerns, alongside the global atmosphere of increased

advocacy about such kind of inclusivity, motivated them to understand “what the content really looks like”.

While the report highlighted a strong trajectory towards an inclusive pedagogical approach, the aforementioned professor emphasised that “there is still a long way to go’’. For example, a gender disparity was observed, with male authors being disproportionately represented in contributions towards course content.

However, a much more noticeable gap lies between the authors from the Global South and North. According to the data cited in the report, 49.87% of the authors used for the de partment’s readings are White Men compared to 30.21% be ing White Women, 10.29% being POC Women and 9.63% being POC Men.

Emma, who studies BSc In ternational Social and Public Policy (ISPP), describes her department’s e colonise research as e and commendable for some speci SP210). Modules as such tackle multiple global regions from crit ical perspec tives an approach that dissects and analyses the limitations of the Anglo/Euro-centric policy systems. Yet, there is still a dire need for diversi cation when it comes to authors in the Development eld, especially with regards to Global South-related content. She recounts feeling shocked that “the localized knowledge of researchers and people in academia are from those who do not belong to the country under study”.

I appreciate the space for the conversation to be had. I feel as if this space and even, the subject matter itself, is a lot less accessible in other LSE departments especially those that are quantitative, from what I have witnessed,” she says.

According to Ha z, the History department provides an immense range of module options, allowing students to specialise in the historic nuances of speci c regional discourse. In particular, he appreciated the opportunity to study the impact of power and protests in Latin America and religious, oriental philosophy from around the world.

However, he argues “there is more research and scholarship available in the West”, especially as a Western institution, possibly making it di cult for the department to diversify resources. ere are also certain parts of modules, in his view, dedicated to understanding the impact of race, ethnicity, and colonial implication on present-day political matters that are well-discussed and acknowledged.

According to Letho, Political eory modules are taught in a Western context using theories from the Global North, with around nine to ten authors studied during the rst year being from the West. Political Science modules (such as GV101), however, do a better job at incorporating examples from Latin America, Africa, Asia and diverse regions, nevertheless failing to eradicate the dominance of Western authors.

other hand, Ha z highlights that “a vast majority of the scholarly readings are by Western academics”, following Western frameworks. He believes that this “does not necessarily detract from the content, given the nature of the eld”.

However, another ISPP student, Leela, commends the efforts taken by this department to courageously question and critically analyse the degree of inclusivity and diversity. “While there are gaps to ll,

ademic content less customisable, especially for those who might want to specialise in the Global South as they are o ered less of an inclusive foundation over the rst two years, with no choice of outside modules.

e only Politics modules available over the rst two years that are region-speci c focus on Europe, which is “not re ective of the student body”, Letho states, unless one resorts to special requests and undergoes concessions just to be able to study specialised modules based on regions outside Europe.

“It’s not from a lack of great scholars coming from the Global South, it’s because not many of them happen to be publishing at the top Western universities and thus, get institutionally sidelined. As a result, we are never going to think critically about development because we are not dealing with people from those contexts,” Letho comments.

Letho adds that the context in which developing countries are discussed is rather narrow, solely tack -

Similarly, one IR student, Jake*, mentioned how several readings stem from theoretical concepts rooted in Western philosophy and further elaborate on ideas that were conceptualised by white male authors from the Global North. He questions the universal applicability of these ideologies in a context of modern-day geopolitical issues.

ling “ethnic fragmentation, corruption, and issues as such.”

While integrating the concept of ‘decolonisation’ could be challenging within quantitative departments – given that the nature of the academic content is rather objective and may not di er in terms of where the scholarship originate from –and the theory is usually cultivated in the West, the Economics department could be more inclusive when it comes to examples and case studies, according to multiples students in the department.

Additionally, the lack of choice of modules one can study in double-degrees makes the ac-

A few interviews represent only a fraction of the degree to which LSE explores, understands, and tackles the subtle neo-colonial in uences within its pedagogical foundations. ere are many more perspectives to hear.

However, they shed light on the conversation: where is the conversation being had and by whom? Is it enough? Is it sustainable? Because this conversation is what paves the way for change and hopefully a future where global institutions provide a platform for any and all intellectual voices to be heard, shared, and integrated into a truly international educational system.

It is important to address the impact of colonial legacy on the academic landscape today, no matter what the subject foci (qualitative or quantitative). It sets a foundation for a necessary, diversi ed knowledge base that every globally proclaimed institution should implement, especially one such as ours with such an emphasis on Political Sciences a very relevant eld of study when it comes to decolonisation.

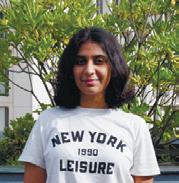

Aaina Saini Opinion Editor Illustrated by Francesca Corno and Sylvain Chan

Online dating has essentially become a coming-of-age university experience. For those of you who believe love is a chemical reaction or are champions of the scienti c method, why would you refute the merits of online dating? An algorithm based method that uses data to match similar people from a large pool who are actively searching for a partner sounds quite foolproof.

e stigma behind the notion of ‘online dating’ is highly misleading. Yes, the term does suggest a lack of human connection, but the online dating

in-person meetup: at the initial meeting stage – whether it be through text or prior interaction – both means of meeting share an unknown, an apprehension of the other party’s true selves and intentions. us even for the hopeless romantic, there is no reason to write o online dating: alternative methods of meeting people also do not guarantee an immediate spark (if such a guarantee even exists).

Furthermore, online dating platforms o er a vastly greater selection of potential matches than the acquaintances your mother or best friend might have. ese dating sites benet from signi cant scale: even if many pro les don’t appeal to you, the sheer ‘numbers game’ increases the chances of discovering someone who aligns with your preferences. In an

I’d say that the ends su ciently justify the means.

In fact, who’s to say that you can’t have your cake and eat it too? Online dating could denitely serve as a powerful augment to your in-person search for a relationship. A er all, would your internship-hungry self swear o LinkedIn and nd referrals or other opportunities exclusively in person?

Online dating also o ers unique advantages to those who may struggle with traditional dating norms. is is particularly true for LGBTQ+ individuals, who o en face challenges in identifying like-minded partners in everyday social interactions. Unlike traditional settings where sexual orientation may not be immediately apparent, dating apps like Hinge allow users to specify sexual preferences. People lament the supercial nature of dating pro les, but there’s a reason why they

stick around: it gives people an unspoken mutual understand ing, and can grease the gears of awkward, sensitive conversa tions in the beginning (like how many kids you want to have). No matter your sexual or ro mantic orientation, or even just your current inclina tions, you can seek out partners who are solely inter ested in physical relationships, those focused on romance, or any mix of the two.

Online dating is supposed to make nding love easier. But the truth is online dating has turned into a game. Instead of fostering real relationships, it encourages people to fall in love with the “idea” of someone

When people create an online dating pro le, they don’t present their true selves, but rather a version that they believe will get the most matches. Carefully-selected pictures, exaggerated bios, and witty one-liners are all part of the performance.

Carefully cra ing an idealised version of yourself to present to others is essentially designing a character in a video game. And just as players assess other characters in a game, online daters judge proles like NPCs rather than real human beings with complexities, emotions, and depth. is leads to a

winner-takes-all phenome

Independent of meeting some one on the bus route home or at a friend’s party, online dating has become much more human and allows for a greater possi bility of truly mate’ - do you really believe that out of 8 billion people, the one for you just happens to shop at your local grocery store?

Finding a partner who ts right

So no matter if you are, online dating has something for everyone.

precisely check all the boxes are disproportionately desired by the many. is creates the opportunity for extortionate subscription plans that prey on the frustrated ‘many’ who are le behind. With the odds rigged against these subscribers, the house always wins in the end.

Yet despite the crushing impact on self-esteem dating apps can have, I o en see people swiping through pro les ‘for fun’ when they’re bored. e pursuit of ‘getting as many options as possible’, has unfortunately trivialised human connection, conditioning us to see romantic prospects as entertainment or a ‘numbers game’.

I agree that online dating allows people to meet individuals they may not otherwise.

without the pressure of predetermined expectations. We meet people in various settings and gradually come to appreciate their personalities, quirks, and values. Over time, we fall for who they are, not because they t an ideal mould, but because of the bond we build with them. Online dating removes this natural progression.

From the moment we see a pro le, we are forced to evaluate someone solely through the lens of whether they t our concept of an ‘ideal partner’. If they don’t check all the right boxes, they are dismissed before we even have the chance to truly know them. is approach encourages us to seek a two-dimensional, ‘perfect match’, rather than allowing a meaningful relationship to develop naturally over time.

ple connect, their matchmaking relies on arbitrary lters like height, job title, or even vague personality traits. In real life, people o en fall for someone unexpectedly, based on intangible qualities that algorithms simply cannot predict or measure. Fortunately, our generation is coming to realise this, as usage has dropped by up to 16% in the top 10 dating apps since 2024.

In many ways, online platforms overcomplicate dating by making it feel like a game or a marketplace rather than a natural, meaningful experience. Real relationships thrive on depth, emotional investment, and effort—things that online dating o en discourages in favour of instant grati cation and endless options.

Yu Yue Cheng Contributing Writer

Taiwan had just experienced the #MeToo movement in 2023 surprising considering that the global movement is over a decade old. e movement was long overdue; I was happy to see so many people stand up to share their experiences, raise public awareness, and see legal reform being taken to address the issue.

Taking a closer look at ‘ e 3 Gender Equality Laws’, the main reform following #MeToo, something didn’t sit right with me: under the new legislation, some of the penalties were aggravated. More precisely, the range of sentencing and nes was revised to have a higher upper limit for certain crimes, and the scope of application of the laws was widened.

“What is the problem with that?” you may ask. “Shouldn’t heavier penalties be an e ective way to achieve justice, or gender equality?”

While heavier penalties may sound intuitive, it is ultimately not a solution to gender violence. For one, this tendency of using criminal penalties as a tool to solve gender inequality and violence goes against the ‘ultima ratio’ principle in Taiwanese law; in other words, criminal penalties should be the last resort for

solving a problem. Additionally, as pointed out by Professor Goodmark, the e ects of carceral policies on gender violence is not well-supported by empirical evidence and therefore remains inconclusive. us, even well-intentioned state intervention can o en prove simplistic and counterproductive: as Amia Srinivasan argues in e Right to Sex, a more carceral policy on domestic violence, neglects the complexity of factors such as poverty and discrimination. She refers to a study in Brazil, where the more carceral ‘Maria da Penha Law’ against domestic violence was ine ective, as poor Brazilian women relied on their partners for income. For them, their partners’ incarceration meant losing their livelihoods, which led many to leave domestic violence cases unreported. is re ects gender violence as a wider issue of structural inequality.

Likewise, the root reason behind gender violence issues in Taiwan is the unequal power relations in social interactions. Sexual assault, harassment, and digital gender violence are all intertwined with a culture that objecti es women and downplays the importance of consent.

In 2024, the Constitutional court in Taiwan made a polarising judgement on the death penalty: it did not abolish, but only restricted the application of this capital punishment. ere was public outcry

against the decision, notably from one of the anti-gender violence movements: on 3 December that year, the ‘White Rose Memorial Service’ was held in memory of a sexually assaulted and murdered female teacher in 2014, protesting for the continued necessity of a harsher death penalty.

Although the indignance of the protesters is understandable, the reason for their protest is on shaky grounds.

e ideas of ending gender violence and the abolishment of the death penalty should not clash as the ultimate goal is to reach a more equal society. e emphasis on a more punitive/carceral policy may only shi our focus away from what’s genuinely important. Similarly, the abolishment of the death penalty also aims to shi our focus back to addressing the fundamental issues of crime, such as the shortcomings of social welfare and the lack of mental health care support. e emphasis on the use of the death penalty on violent crimes and the unpredictable execution of death row inmates only allows the Taiwanese government to avoid addressing the root causes of crimes. More intuitively,

abolishing the death penalty leads us to a less carceral policy, which will force the government to direct meaningful e orts towards solving the structural issues behind crime. Since both movements have similar aims to address fundamental structural inequalities in society, there is a powerful potential for collaboration.

Yet the anti-gender violence movement’s stance on a more punitive policy is unclear. roughout their decades-long advocacy for legal reforms, activists protesting for harsher carceral policies have made notable contributions to the anti-gender violence movement’s successes such can be seen through the White Rose movements in the 2010s (di erent from the 2024 White Rose) in Taiwan. However, this does not mean that all their advocacy is about raising the penalties.

Despite this, the idea of Abolition Feminism (AF) shows that a clear alliance between the two groups remains feasible. It is a series of social movements that combine the abolition movement and feminist perspectives, and calls for radical change in criminal justice systems – even the abolition of prisons in some cases – whilst

‘For them, their partners’ incarceration meant losing their livelihoods, which led many to leave domestic violence cases unreported.’

(Featuring the Editorial Board)

• “Couples should social distance by at least one metre in public.” - Anonymous

• “I hate the texture of chocolate.” - Emma

• “Galentine’s is better than Valentine’s.” - Janset

• “Dry owers and LEGO owers are better than fresh bouquets.” - Jess

• “LEGO owers are silly. I might as well print out a picture of a rose and give it to you.” - Anonymous

• “Bouquets are not a legitimate gi .” - Suchita

centering the experiences of the most marginalised groups. e movement engages in vital community work that supports victims and o ers interventions to gender violence. Despite the fact that the abolishment of prisons might be radical for Taiwan, we can still adapt AF’s core idea into Taiwan’s legal context to create an approach of ‘Anti-Carceral Feminism’. Given the existing in uence of the anti-gender violence movement, this idea holds strong potential: in a study by Professor Chia-Wen Lee, there has been a strong relationship between the changes in criminal policies and the advocacy of the anti-gender violence movements throughout modern Taiwanese history. is can be put into practice by taking AF’s focus on the most marginalised groups. We could make the unheard voices in Taiwanese society heard, such as the (o en overlooked) migrant homecare workers currently facing sexual harassment. is presents a perfect opportunity to follow AF’s strategy of community work and advocacy.

While the relationship between these two movements in Taiwan is still ambiguous there remains a promising potential for collaboration. Only when the con ict is replaced by an alliance through ‘Anti-Carceral Feminism’ can we make meaningful change to the violence we want to end. Read the full article online.

If breaking news happened every hour, would it still hold the same weight?

With each new generation, the consumption of traditional media continues to decline. While LSE students are more likely than others to sit down and read the Financial Times or the Wall Street Journal, 52% of UK adults now use social media as their primary news source. What is even more alarming is that 37% of respondents in 2024 said they primarily encounter news through social media. Social media has a much faster pace of news reporting and wider spread coverage, beating out the traditional journalism publication format. is shi isn’t necessarily a bad thing—society has become more aware of real-time news due to the constant ‘publication cycle’ of social media. However, the accessibility and speed of social media also present another can of worms: the prioritisation of virality over journalistic integrity in the race for revenue. Are we witnessing the death of traditional publication and the rise of citizen journalism?

Traditional news outlets were once the gatekeepers of journalism, requiring aspiring journalists to navigate high recruitment barriers and have years of experience before a chance to even publish under their publication banner. Older forms of media – such as TV stations, newspapers, and public radio – were exclusive platforms with speci c strict requirements before mass dissemination. However, as we see the rise of social media and what seems like a general addiction to social media platforms, alternative platforms like podcasts and short-form videos have expanded, causing a massive decline in readership for traditional media. e

result? Citizen journalism. More people are able to enter the market and can pro t o of journalistic research without having to do a few years of co ee runs beforehand. is allows a wider range of journalistic research to be pursued, as more people can investigate without the barriers of traditional journalism.

e Blake Lively v. Justin Baldoni lawsuit is a case in point. If you’ve spent any time on TikTok recently, you might have encountered the celebrity drama revolving around the two actors in a battle for public favouritism. More recently in the development of the case, a TikTok journalist under the name ‘Bee Better’ discovered and provided proof of a targeted campaign against Baldoni on behalf of Lively, successfully lending support to Baldoni’s case. Here, the strengths of citizen journalism are clear: they can discover and disseminate information that traditional outlets either overlook or are slower to report on. e advantage of time and freedom to investigate can be seen with the plethora of video essays online, with cases like YouTuber Megalag’s exposé on the $4 billion company PayPal Honey. Citizen journalists are better able to in uence and shape the opinions of the public, o en with the luxury of being able to explore topics that resonate more with their audiences.

With anyone able to publish content online, traditional journalism has not only declined in readership but also lost its dominance over the job market, weakening its in uence on the masses. is shi is re ected in not just the decline in newspaper circulation but also the decrease in digital subscriptions for traditional journalism platforms: according to the PressGazette, the percentage of the UK population digitally subscribed to legacy outlets fell to 8% in 2023, down from 9%.

As legacy outlets struggle to

maintain their grip on the public, the issue of potentially false information intensi es. Anyone can report, publish, and share viral opinions without the more stringent checks and balances once guaranteed by professional journalism. And when you’re mindlessly scrolling in the dead of night, you tend to let your guard down and take what you’re reading at face value—especially if multiple people share the same perspective. As much as the viral Lively v. Baldoni drama makes the case for citizen journalism, it is also a warning against immediate consumption of information without proper context or veri cation. e rapid back-and-forth of public consensus between both sides a er the lawsuit was led, and again a er the counter-lawsuit, demonstrates the issue of real-time news with little to honestly no quali cation. While this particular case may not be the most signi cant in terms of misinformation causing damages, it highlights how the public’s perception is shaped by such fast-moving content, leaving even some of the public to question their subjection to media manipulation.

e ease in access to let your opinions be heard through podcasts or short-form videos without veri cation erodes journalistic integrity. Unlike traditional media outlets, citizen journalism prioritizes speed over accuracy, o en sidestepping the fact-checking process.

Rather than being considered ‘true’ journalism, if that even exists, TikTok should instead represent public consensus. It is swi ly made and opinion driven, as the public decides their views on certain topics through the people’s court. As we move forward, there is likely to be an increasing rivalry between traditional media and social media, with the latter being shaped and reviewed by the public. ere are going to be signi cant implications

if social media journalism is trusted without certain formal checks and systems of accountability.

How, then, should traditional journalism change in response?

I think it is important to distinguish between tabloid gossip and investigative journalism: while platforms like TikTok, Instagram, and Twitter have le traditional journalists in the dust for celebrity news, investigative journalism covering politics, business, and global a airs remains a unique advantage (on average) for traditional outlets. Serious reporting requires resources, major platform backing and credibility—things citizen journalists nd more di cult to get a hold of. e credibility of traditional media will be unlikely to be replaced by social media. A er all, you would prefer to have a feature article about you in a reputable publication like Forbes than an Instagram Reel! With this in mind, social media should serve as a tool to amplify awareness, allowing you to discover news and later read up more about it through traditional media. Take another case: Luigi Mangione and the murder of UnitedHealth CEO Brian ompson. e case was broadcast across TikTok, with users commenting on videos to share their thoughts or updates. Social media is longer a space solely for dis cussing news; it’s where you discover

Citizen journalism is also seen to be increasingly morphing and utilised to support traditional journalism. Citizen journalism can reach a broader audience, as shown by content from people directly a ected by events like the war in Ukraine. Not only can they be reported more instantaneously than traditional journalism, they also provide a strong sense of reality and raw emotion to otherwise impersonal headlines, and point more people to stay aware of the con ict through other outlets. In this way, citizen journalism is adapting itself to a promising coexistence with traditional news.

As we look toward the future of journalism, there is a challenge for citizen journalism in maintaining credibility and bene ting o of ‘rage bait’ or the virality of fake information. Traditional media continues to decline in its ability to capture public attention and sustain revenue in an era dominated by digital media. Traditional media must adapt to evolving public preferences, especially in response to declining pro ts. While the joy of reading a physical newspaper – something us at e Beaver can certainly appreciate – remains steadfast, the industry faces increasing pressure to embrace social media and ensure credibility in a landscape where anyone can publish news. e challenge is in ndingcreating systems ofzen journalism nding a balance in the coexistence of the two

Warm sticky toffee pudding served with vanilla ice cream.

For people who love time to themselves and quiet, cozy nights in.

Banana split served in a long dish with favours everyone will fnd delectable.

For those who love quality time with company.

Strawberry tiramisu ripple cake.

For those who love time with family and their partners. Some say you’ll marry the one you share this with!

Coconut sticky rice with a side of tanghulu mangoes.

For those who love success in life—legend has it, those that eat this will get internship return offers!

With Valentine’s Day whimsy in the air, it is no better time to celebrate love and its different forms.

Take a look love language-based will be paired sert of

Chocolate Vanilla

Decadant and smooth; for those who enjoy physical touch.

A comforting sic; for those enjoy words affrmation.

Buttery and light; for those who enjoy receiving gifts.

Perhaps take a look at our bakery’s multimedia menu and see what piques your fancy!

look at which language-based syrup paired with your desof choice!

Gin key lime pie with rum chocolate decorations.

For those who love indulging themselves. Hey, we get it—life gets tough. Just make sure to eat this in moderation.

Panna Cotta and lemon jelly served in a small glass.

S’more to Love

Milk chocolate s’mores with shredded coconut and sea salt sprinkled on top.

For those who love loving; a mosaic of everyone they’ve ever loved.

Vanilla Maple Deep and earthy, never tiring; for those who enjoy quality time.

comforting clasthose who words of affrmation.

Strawberry

An uplifting sweetness; for those who enjoy acts of service.

For those who love hating: being a hater is important for the economy, just don’t let it sour you too much.

Show this coupon to a friend and now they owe* you a drink!

*Legitimised on the suspension of disbelief. May not work on all friends.

EDITED BY SKYE SLATCHER

AND JO WEISS

by JO WEISS

It has been over a decade since Chris McDougall published his seminal book Born to Run, a title that has sold over three million copies and appeared on the New York Times Best Sellers list for four months. Drawing on human evolution and the modern-day case study of the Tarahumara, an indigenous tribe with an a nity for endurance running, McDougall argued running is a part of human nature. According to McDougall, “If you don’t think you were born to run you’re not only denying history. You’re denying who you are.”

While McDougall cites Palaeolithic times, modern history is likewise rich with stories of people turning to running, underscoring its enduring relevance to humanity. A notable example is found in the running boom of the 1970s, during which around 30 million Americans took up the sport. Participants included the likes of former President Jimmy Carter, who engaged in daily runs behind the White House and infamously failed to nish a road race a er su ering from exhaustion. e increased interest in running catalysed the creation of several major races, a phenomenon that reverberated globally. London Marathon co-founder Chris Brasher, for instance, was in part inspired by the American passion for running that he witnessed during the 1979 New York Marathon.

Concurrent with growing societal popularity, coverage of running emerged across media platforms, literature, and academia. Central to 1970s scholarship was the notion of ‘running addiction’ and whether it created more bene ts or drawbacks. While psychiatrist William Glasser (1976) postulated long-distance running induced a positively addicted (PA) state that strengthened coping mechanisms for life’s stressors, sport psychologist William Morgan (1978) emphasised its negative implications. Suggesting an addiction to running fuelled disassociation, Morgan argued runners may overlook warning signs of serious injuries as well as broader social and professional obligations.

Beyond investigations into the implications of running, scholars attempted to trace its origins. McDougall’s assertion that humans are natural-born runners draws on the endurance pursuit (EP) hypothesis, introduced by biologist David Carrier in 1984. is theory advances the idea that humans developed endurance running traits to optimise hunting, enabling them to track prey to exhaustion amidst hot climates. Two speci c features of human anatomy stand out, namely the ability to dispel metabolic heat through sweating and the fatigue-resistant bres of our locomotor muscles. ough

some critics are sceptical that early humans partook in endurance pursuits, a 2024 study published in Nature Human Behaviour supports its ndings through an ethnohistoric database and mathematical modelling.

e abundance of studies on running’s physiological and mental bene ts seemingly supports that idea that humans are inherently designed for running. Regular running has been shown to improve cardiovascular health, immune function, and sleep. Additionally, it has positive e ects on mental wellbeing due to the release of endorphins, which can improve mood and alleviate symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Heightened awareness of these numerous health bene ts is surely part of the reason the world is experiencing a running boom not unlike that of the 1970s. Amid the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, running saw a surge in popularity, as people sought a safe, accessible way to stay active and manage stress levels. Running continues to captivate many, with 2023 Google data evidencing that searches for “running route near me”, “how to get into running”, and “how to start running” have increased by 50%.

Yet, it is not just the prospect of better health that is driving interest; running has arguably become a social trend. While some may run in search of the elusive, almost mythical ‘runner’s high,’ others are motivated by entirely di erent reasons—and luckily, modern run clubs cater to all. Fuelled by social media platforms like Instagram and TikTok, run clubs are now heralded as the ‘new dating apps’ or the perfect way to meet like-minded friends. In particular, the craze of run clubs is largely an urban phenomenon, with major cities such as London o ering a dizzying array of options. To illustrate, Friday Night Lights features runners dressed in neon attire, jogging to explosive pop music as a healthier alternative to clubbing, while ese Girls Run o ers a communal running sisterhood, and Track Ma a an outlet for speed enthusiasts.

e newfound popularity of running brings an increase in social media coverage, as health and wellness narratives skyrocket. Donning the latest HOKA shoes, AeroSwi shorts, and hydration vests, in uencers around the world post carefully curated shots of their running routes, toned legs, and post-run co ees. Such visuals are a far cry from McDougall’s message on running: inspired by the Tarahumara, who o en run in sandals, he suggested that ‘barefoot running’ could reduce injuries. It is questionable whether running completely barefoot is a feasible option for the average runner, but perhaps a more applicable insight from McDougall is that the Tarahumara had “never forgotten what it felt like to love running”.

Emphasising that running is o en viewed as a gruelling, punishing undertaking, he praises how the Tarahumara nd joy in the sport by embracing it as a natural human ability. is is also re ected in their running style, with one seasoned endurance runner le stunned by how “they seemed to move with the ground, kind of like a cloud or a fog moving across the mountains”. On the ipside, it can be argued that no matter what drives people to run –whether pure joy for the sport, a desire for improved health, or the in uence of social media – running’s widespread appeal a rms its enduring connection to human nature.

If running is indeed a natural human a nity, I certainly struggle to tap into mine and nd joy in what can feel like a relentless, uphill battle. To endure, I typically zone out or saturate my mind with music and podcasts to distract myself from the present moment, which does not exactly exhibit a love for running. However, in rare, eeting moments, I too can feel the ecstatic freedom purported by passionate runners, and the idea that running is engrained in our very nature becomes more tangible. During those moments, as the wind rushes past me and I feel my heart pounding, there is a visceral sense of being alive—a feeling that grows more meaningful in an increasingly super cial reality. Whether or not humans “were born to run”, it is undoubtedly a powerful belief with the capacity to inspire dedicated training. I know I’ll keep that in mind the next time I try to motivate myself to run through the cold, wet, and unforgiving London winter.

Jacky (First-year Actuarial Science)

Taking part because: I want to get out of my comfort zone

Greatest strength: script writing in LSE vshow 2025

Seyuri (Second-year Psychological and Behavioural Science)

Taking part because: I had two big operations last year which le me unable to do sport for almost two years. I needed an excuse to get back on my feet, feel more of a part of LSE, and get back to feeling my powerful self.

God’s Favour (Second-year Management)

Taking part because: Lost a bet.

Greatest strength: God’s Goodness, Mercy, and Favour

Kiran ( ird-year Philosophy and Economics)

Taking part because: I wanted to challenge myself mentally and physically. e training is hard but I already feel stronger than when I started—that feeling is so rewarding.

Greatest strength: I’m very headstrong—when I set myself a goal, I do everything in my power to achieve

Jody (Alumna, MSc Organisational and Social Psychology)

Taking part because: Love of gratuitous violence

Greatest strength: Roundhouse kick

Lucile ( ird-year Social Anthropology)

Taking part because: LSE boxing society has been a foundational aspect of my development, having spent more time in training and sway than in lectures.

Greatest strength: My drive and motivation, needed to survive the four hour ursday training sessions a er a heavy Wednesday night. I’m also pretty good at exclusively shadow boxing people double my weight class.

Amara ( ird-year Politics and Data Science)

Taking part because: I just like people cheering for me lol. No but seriously I love challenging myself to try new things and I wanted to use my strength from pole dancing in a di erent way and hopefully get even stronger (to be better at pole dancing haha). In the process I have learned that I love boxing for how empowering it is to be able to take a punch and bounce back!

Greatest strength: Um, delusion :)

Tom (MSc Criminal Justice Policy)

Taking part because: To challenge myself Greatest Strength: Remaining calm under pressure

Sakshi Nair (MSc Behavioural Science)

Taking part because: Because I think it’s high time that ‘ ght like a girl’ sounded more like a warning rather than an insult.

Greatest strength: Well, coach says I’ve got amazing footwork; so I guess you can say I’m always one step ahead.

Diya (General Course)

Kareem ( ird-year Mathematics, Statistics and Business)

Taking part because: I want to push my limits in a new sport.

Madi (First-year Law)

Taking part because: I trialled for Fight Night because it looked like so much fun. I haven’t watched Fight Night before and had no idea it even existed before joining the LSE but honestly, everything about it excites me!

Greatest strength: Based on my excitement, I think my greatest strength is that I have persuaded myself into thinking it won’t be too painful on the night!

Taking part because: I wanted to stay physically active in London and hold myself accountable, so I joined Boxing. I heard about how intense Fight Night training gets, so I thought I could at least be considered as a reserve. en, to my surprise, I got a message from Savannah, and ever since, I’ve been pushing myself to improve, enjoy the punches, and consistently show up to training. Greatest strength: composure and calmness when sparring. I just hope I can maintain that in a roaring, crowded room.

Evangelia (MSc in International Political Economy)

Taking part because: I did kickboxing in Paris last year and fell in love with boxing. A friend told me about Fight Night at LSE, and honestly, when will I ever get a chance to do something like this again? I nd the sport incredible, and I’m super grateful for the opportunity to step into the ring.

Greatest strength: In boxing or in life? In life, I’d say connecting with people. In boxing, let’s go with my jab-cross combo—ideally connecting my glove with my opponent, not just the air.

Rihan (Second-year ISPP and Economics)

Taking part because: Great sport, great event last year— why not be a part of the action?

Greatest strength: I’d like to think my boxing…I guess we’ll nd out.

Sertara (MSc Political Science)

Taking part because: I wanted to secure a free ticket to Fight Night!