13 minute read

The Fall of the Mighty Cod

Representative Jeff Van Drew Tours Atlantic City Boat Show

Saturday, February 29, 2020, Congressman Jeff Van Drew (NJ-2) toured the Atlantic City Boat Show to visit and check in on his marine industry constituents. Prior to wining the 2 nd district seat, Mr. Van Drew was solidly behind fishermen and all the marine related businesses in south Jersey while serving in the New Jersey Assembly and Senate. It was Mr. Van Drew who worked hard with Governor Chris Christie to stop an unnecessary saltwater fishing license. Jeff also led the charge in the New Jersey Senate to reduce the sales tax on boat purchases.

Advertisement

New Jersey’s 2 nd

District Congressional District is the largest water district in the State. From Barnegat Light to Cape May and up the Delaware River to Gloucester County, the 2 nd District includes numerous recreational fishing ports, marinas, and businesses. Van Drew is a staunch patriot and believes in the personal freedoms we all enjoy as Americans. Please remember Mr. Van Drew in November.

Van Drew (L) discusses marine industry concerns with Sean Healey of Viking Yachts and Valhalla Boats during the AC Show.

MIGHTY CODFISH

New England’s iconic cod stocks, which once provided huge fortunes for those in international trade, are now but a shadow of their former abundance due to a deadly combination of runaway fisheries technology and lackluster, reactive management.

By Capt. Barry Gibson RFA New England Regional Director

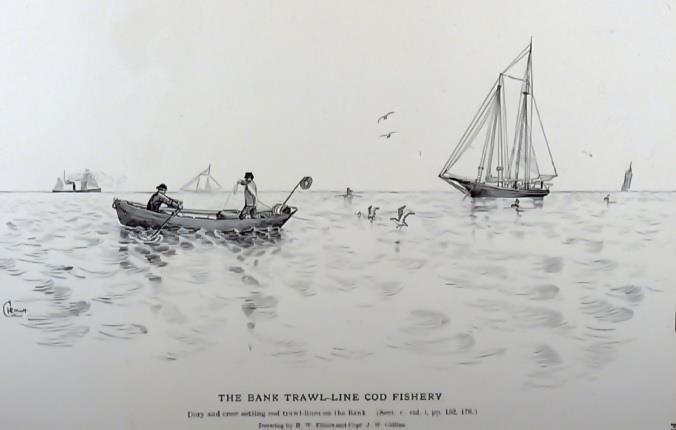

It’s the call they’ve been waiting for, and Asa Allard and Harland Guidry hurriedly prepare their little boat. Thwarts are shipped, the bottom plug is jammed in, and oars, pen boards, water jug, bailer, bucket, gaff, bait knife, sail and mast, and three tubs of hooks and line are hastily stowed. The 20-foot dory is lifted by means of a block and tackle secured to the schooner’s shrouds, and swung overboard.

The two fishermen jump in, and the dory drifts astern. Its painter, attached to a pin in the ship’s taffrail, comes tight and the little craft is towed effortlessly over the gentle swells. Seven more dories, each manned by a pair of fishermen, are swung over and lowered into the sea, each attached to the one ahead of it. Soon all eight are towed in a string, looking for all the world like a line of orderly ducklings following its mother. Forty-one-year-old Captain Jonas Walford swings the bow of the 116-foot Gloucester-based banker Lillian Emmons due east. He likes the water depth he has found with his lead-line, as well as the coarse gravel embedded in the tallow at the bottom of the lead. Within a few minutes he makes the signal for the trailing dory to let go. The remaining seven are distributed at equal distances over a stretch of nearly four miles. The schooner hoves-to as Walford keeps one watchful eye on the weather and the other on those of his charges within view.

Allard ships the dory’s oars and begins rowing, while Guidry secures the end line of the first tub of gear to a small iron anchor to which a sturdy wooden keg is attached. He throws the anchor over and stands in the stern, whirling the coils of line and hooks out of the tub with his short heaving stick. All three tubs, their lines tied together, are finally emptied, and over a mile of ground line festooned with 1,500 forty-inch snoods and

1,500 hooks baited with herring settle to the sea floor 32 fathoms below. Two hours creep by, and it’s time to haul the line back aboard. Allard inserts a lignum-vitae roller in the gunwale and pulls the anchor and buoy into the dory. He detaches the longline and stands in the bow and retrieves it, hand-over-hand. Guidry positions himself behind Allard and coils the line back into the tubs, knocking off any untouched baits. Each fish that comes over the roller is dehooked by a circular motion of Allard’s arm and tossed into the bottom of the skiff. Those that have taken the bait deep are passed behind to Guidry, who frees the hook by taking a few turns of the snood around his wooden gob stick and twisting it sharply. handsome with mottled olive-brown backs, pale lateral lines, and pearlescent bellies. The occasional 30- or 40- pound cod makes an appearance at the roller along with a scattering of other groundfish, as do a variety of undesirables –skates, sculpins, and the hated dogfish –which are knocked off the hook with a spirited slat against the dory’s gunwale. The hauling process takes several hours, and when the lines are finally in and the gear is stowed, Guidry ships the oars and pulls for the waiting schooner. The painter is caught, the two men hand up their tubs of line and bare hooks, and proceed to pitch their catch –nearly 1,500 pounds of cod plus a handful of haddock, hake, and wolfish into pens on the schooner’s deck.

And what fish they are! Most are cod weighing from six to 25 pounds, well-proportioned and But the day is not over. Allard and Guidry will join the other 14 dorymen in splitting, gutting, wash-

ing and icing down the day’s catch, which totals over six tons of groundfish. After that the tubs of longline must be re-baited. Cold, damp and tired, the men are finally done at midnight but will be back in their dories before dawn. Sleep is a scarce commodity aboard the Lillian Emmonswhen seas are calm, the cod are biting on the bank, and there’s money to be made.

Fast -Forward 106 Years

We are four miles southwest of Maine’s Monhegan Island, an area that once held one of the highest concentrations of cod in the world, in my 28-foot center console. It is a beautiful, calm July morning and I alternately scrutinize the LCD screen of the Furuno FCV-585 with its 1000-watt transducer and that of the Garmin 4212 chartplotter. The bottom contours all look vaguely familiar, as do the ridges and valleys displayed on the color fishfinder. But what I can’t find are the distinctive scratches of cod that used to appear so regularly back in the 1970s, etched into the paper by the stylus of my Gemtronics depth recorder.

Perhaps the fish are simply hiding, so Chuck, Mark and I send ten-ounce Vike-E jigs and green, soft-plastic paddletail teasers to the bottom 210 feet below. We work the jigs. Nothing. We make a move to the northeast and try again over a lump 186 feet deep where a charter party of mine once took over 300 pounds of cod in a single drift. It’s easy to find with the high-tech plotter, but there’s nothing there. Frustrated, I work another mile to the south and stop on a spire in 230 feet of water. Chuck brings in a nine-inch redfish, and Mark foul-hooks a cunner of about the same size. Finally, at the edge of hard a ridge several miles to the north in 160 feet of water, Mark boats a cod -- and it’s a beauty. But it’s only 11 inches long, so he carefully removes the hook and drops the fish back into the water. It floats belly-up, and minutes later two seagulls swoop down and squabble over the tiny prize. We end the day with two cusk and four legal-size redfish, which Chuck and I decide Mark should take. On the way home from the marina I stop off at Hannaford’s Supermarket to pick up something for supper. I peer into the seafood case at the back of the store. Some grayish-looking, frozen-at-sea haddock marked “FAS –Product of Iceland,” two “Jet Fresh” South American swordfish steaks that look like they’d abandoned all hope of ever seeing the inside of a gas grill, big shrimp from Thailand, crab from Canada, a few farmraised salmon steaks, and a stack of fresh cod fillets at $11.95 per pound all compete for space in their bed of crushed ice. I grab a package of chicken and head for the checkout counter. A much younger Captain Barry hefts a 45-lb. cod jigged back in the 1980s when they were still caught in good numbers in Gulf of Maine.

The Big Business of Cod The Atlantic cod was, and still is, is one of the most commercially important fish in the entire world. Although these nutritious and tasty whitefleshed bottom dwellers range throughout much of the Northern Hemisphere in cold salt waters, nowhere is their value more revered than in the northwest Atlantic Ocean. Portugese, Spanish, French and English fishermen sailed to the Grand Banks off Newfoundland beginning in the early 1500s to load up on cod, which they dried or salted and brought back home to be sold for a tidy profit. In the early 1600s, Capt. John Smith launched several expeditions from England to map the east coast of America from Chesapeake Bay to Penobscot Bay, and became rich from the cod he would return with and sell. Smith’s fishing ventures off New England helped enhance the region’s early popularity, and soon British fishing colonies were established on and around Cape Ann and the islands of Monhegan and Damariscove off Maine. When explorer Batholomew Gosnold landed in New England in 1602 during an attempt to find a passage to Asia, he officially changed the name of the spit of land known as Pallavasino to Cape Cod because his ships were continually “pestered” by these fish. The Pilgrims, who arrived in 1620, had virtually no experience in fishing or even a taste for fish, but in time learned the business and soon established fishing stations along the Massachusetts coast to take advantage of the abundance of easilycaught cod. By the early 1700s fast and able fishing schooners were being built in Gloucester, and soon the fleet swelled to 400 vessels that worked the Grand Banks, Georges Bank, and the grounds in the Gulf of Maine. connecting New England with Europe, the Caribbean, and Africa. Commerce flourished and people prospered, and soon New Englanders -- British colonists -- began to suspect that they didn’t really need the supervision of England any more. The catching and trading of virtually unlimited amounts of cod, which triggered numerous political and economic skirmishes along the way, built fortunes for the new “Codfish Aristocracy” and a gilded “Sacred Cod” was even hung from the ceiling of the Boston Town Hall in 1747, a testament to the fish’s importance in New England. All this continued right up through the Revolutionary and Civil Wars and into the 20 th

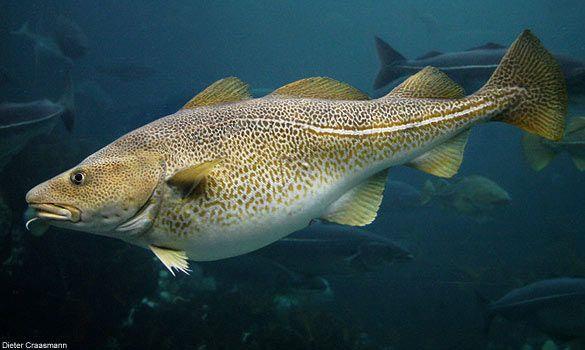

century, and in 1906 the first steam trawler was introduced. This would ultimately change everything, as codfish would no longer have anywhere to hide. Fast Handsome, Hungry & Horny The reality is, of course, that the Atlantic cod (Gadusmorhua) is simply too busy eating or spawning to think about hiding from a net. The species, which developed into its current form about 120 million years ago, ranges in North America from Baffin Island to Cape Hatteras, but the nutrient-rich Gulf of Maine as well as Georges Bank, a shallow and fertile oval of ocean bottom some150 miles long and 75 miles lying 65 miles east of Cape Cod, hold most of the cod that exist today. This heavy-bodied groundfish, so named

Copious amounts of fish were landed, and “Cod Trade” routes involving salt and dried cod, salt, sugar, tobacco, molasses, rum, and even slaves were soon established,

because it lives close to the sea floor or “ground,” can grow to better than 100 pounds although five- to 50-pounders are more commonly caught today. Cod migrate back and forth throughout the Gulf of Maine to feed and spawn, their routes dictated largely by the time of year, and there’s clear evidence of intermixing with the Georges Bank stock. And they are -- as noted above -- a handsome fish. The color of their backs, upper sides, and six fins vary widely from almost black to brown to olive green to yellowish to pale gray, adorned with speckles of varying colors. Bellies are whitish and often tinted with the color of the bottom habitat from which they’re caught. Shallow-water “rock cod,” which tend to be territorial rather than migratory, range from brown to brick red. All cod have a pale lateral line that stands out against the darker sides, and a fleshy barbel underneath its chin that is thought to aid them in finding food on the bottom although these fish are thought to be primarily sight-feeders And if there’s one thing a cod is good at, it’s eating. Larval cod only six days old start chowing down on copepods and tiny crustaceans, and as they grow (they’ll reach six or seven inches in the first year) their diet expands to small worms, barnacle larvae, and a great variety of invertebrates. Mature cod greedily feast on clams, mussels, cockles, crabs, lobsters, shrimp, starfish, sea squirts, squid, and a smorgasbord of finfish including their own progeny. If it’s organic and will fit in its mouth a codfish will eat it. Cod also excel at spawning. In the western Gulf of Maine this takes place in 50 to 250 or more feet of water depending on locale. Primary spawning grounds include the stretch of water between Cape Cod Bay and Massachusetts Bay, from about three to ten miles offshore, from December through February; the Stellwagen Bank area in April and May; and a stretch of bottom extending from Ipswich Bay up through southern Maine in December and January. Several smaller spawning grounds can be found off the southwest coast of Maine. Female cod are remarkably fecund. The average fish lays about one million eggs, but that jumps to three million or so when she’s 40 inches long and closer to nine million at 50 inches. The fertilized eggs are buoyant, drift with the currents, and incubate for 10 to 40 days depending on water temperature. The young cod float helplessly and are vulnerable to all sorts of predators including other finfish, birds, and jellyfish, but the few survivors eventually work their way to the bottom and seek out areas of cobble and vegetation that will afford protection as they grow. If every female cod produces just two offspring that reach sexual maturity out of the millions of eggs she will lay in her lifetime, the population will remain stable. But that stability will only continue if at least a certain percent of those cod get to remain in the water to spawn themselves….and that’s the rub. Too Much Tech, Not Enough Fish By 1930 it was evident that that New England’s groundfish fleet, now made up primarily of mechanized trawlers capable of towing efficient nets, was able to catch more fish than could be replaced by nature. In addition, the small mesh size of the nets captured tens of millions of juvenile and thus unmarketable cod and haddock annually that were shoveled back overboard dead, and concerns about the health of the groundfish resource were soon raised. World War II reduced the size of the fleet somewhat as fishing boats were requisitioned for war duty, but demand for fish by the military and the general citizenry soared. After the war the return of the vessels to the fishery, coupled with reduced demand for fish, resulted in lean times for the industry and sparked a number of government subsidy programs that would continue for decades. The early 1960s heralded a new threat -- huge foreign factory trawlers that had discovered the abundance of groundfish on Georges Bank. These ships, capable of both catching and processing, came over from the USSR, East Germany, Spain, Poland and Japan and scooped up hundreds of thousand of tons of cod and haddock.