54 minute read

Dave Grohl shares four songs he wishes he wrote

Playlist SONGS TO PRAISE

Foo Fighters frontman Dave Grohl has written some hits in his time, but here are four he wishes he had.

Last year was meant to be a big one for Foo Fighters’ Dave Grohl. In the spring, the L.A.-based drummer turned band leader was set to release a new album, followed by a world tour. COVID-19 thwarted those plans, but Grohl didn’t sit still—instead, he shared short biographical stories on Instagram to entertain fans, engaged in an epic online drumming battle with 10-year-old Zulu-British prodigy Nandi Bushell and revisited the music of his youth, rediscovering songs he wishes he wrote. In celebration of the Foo Fighters’ 10th studio album, Medicine at Midnight, finally being released in 2021, the 52-year-old reveals four of the songs that have inspired him—and made him envious that he didn’t conceive them himself. foofighters.com

KIM WILDE “KIDS IN AMERICA” (1981) “Every punk-rock boy I knew was hopelessly in love with Kim Wilde, and so was I. That’s why I recorded my own version of ‘Kids in America.’ It was in the days before [I joined] Nirvana and I did it on a whim. I was at my friend’s basement studio and I said, ‘Let me record this thing.’ It’s an iconic, anthemic song from the ’80s, and I love it as much as I loved her!” BAD BRAINS “SAILIN’ ON” (1982) “Bad Brains were America’s greatest hardcore punk-rock band in the ’80s. They were from Washington, D.C., and were the best live band I’ve ever seen in my life. I was in love with their music—it was so fast, so distorted, so dissonant. It made me want to drink a hundred beers and break windows. Now, if that’s not a good enough reason why I wish it had been written by me …” PATTY & MILDRED HILL “HAPPY BIRTHDAY TO YOU” (1893) “I wish I had written ‘Happy Birthday [to You],’ obviously, because I’d be making so much more money right now—it would be like owning the rights to pizza. And maybe it would get me some respect at home, too. I have one daughter who wants to be a musician, and two [others] who look at me like I’m a fucking janitor. They’re like, ‘Oh, that’s Dad’s job. Whatever!’ Maybe one day …”

JOHN LENNON “IMAGINE” (1971) “I really wish that I had written ‘Imagine’ because it’s such a beautiful song with a really timeless quality—the song just never sounds old. When I was young and I first started playing guitar—around the age of 10 or 11 years old—I would sit and strum along to [John Lennon’s] records all day long. That’s how I learned to play guitar—John was my teacher.”

LIFE ON THE EDGE

Many of us just spent a year or more in lockdown, but the time for full-throated adventure may finally be upon us. Whether you’re ready to plan or still in the dreaming phase, here are some wild images, all taken by top adventure photographers in wilderness locations throughout the U.S., to stoke your imagination. Flip through the portfolio and picture yourself getting out there in a big way.

Words PETER FLAX

Climber Zak Krenzer approaches the summit of Forbidden Peak, located in the heart of North Cascades National Park in Washington. The route up the mountain’s west ridge is celebrated in the iconic guidebook Fifty Classic Climbs of North America. Experienced climbers say that there’s no easy way off the majestically rocky, 8,815-foot peak—that the adventure is only half over after you tag the summit.

Kayaker Tim Kelton paddles over a waterfall, backwards, on Oh Be Joyful Creek, a Class V thrill ride near Crested Butte, Colorado. In less than a mile, the creek drops 600 feet, meaning super-competent paddlers can bomb the whole stretch in less than 10 minutes. This is not a spot for intermediate paddlers to learn new skills; locals like to call it Oh Be Careful Creek for a reason.

Locals like to call this Class V screamer Oh Be Careful Creek for a reason.

STRONG PULL

AMERICAN FORK CANYON

Climber Lizzy Ellison muscles her way up Teardrop, a 5.13a route in American Fork Canyon. Located in the UintaWasatch-Cache National Forest, less than an hour from downtown Salt Lake City, American Fork is a wonderland for sport climbers, with hundreds of routes—from 5.7 to 5.14c— on the steep, pocket-filled limestone walls.

DUNHAM SLOT CANYON

Canyoneer Emily West rappels into the depths of Dunham Canyon, a slot canyon located near Kodachrome Basin State Park in southern Utah. The technical part of the canyon is not long—maybe 300 meters—but delivers a lot of photogenic payoff for those with the right skills.

It’s not exactly easy to get inside Dunham Canyon—but the visual payoff is worth the effort.

LINE ART

YOSEMITE VALLEY

Climber Brian Mosbaugh hits out on the “Long Rostrum” line, which is 120 feet long and hangs almost 2,000 feet above the floor of Yosemite Valley. This area is where highlining truly took off in the 1990s, as Dean Potter was the first to walk the Rostrum line untethered.

The “Long Rostrum” line sits nearly 2,000 feet above the floor of Yosemite Valley.

FOOTLOOSE

VIRGIN, UTAH

Freestyle mountain bike pro Rémy Métailler—who originally is from France and now calls Whistler in British Columbia home—hucks with real artistry on the legendary hills near Virgin, Utah. The terrain shown was home to an earlier iteration of Red Bull Rampage.

You can ride where Rampage was originally held, near the edge of Zion National Park.

Sometimes you can taste the sharp edge of adventure without any technical wizardry or physical suffering. Here photographer Matt Baldelli captured his girlfriend, Megan—now his wife—as she sips sunrise coffee after a frigid fall night in the Berkshire Mountains of western Massachusetts.

The deck of the Perrine Bridge sits a whopping 486 feet above the Snake River.

JUMP SCARE

TWIN FALLS, IDAHO

With the sun rising, a participant in an educational program at the Snake River BASE Academy jumps off the Perrine Bridge in Twin Falls, Idaho—the eighth-highest bridge in the U.S., soaring 486 feet over the Snake River. Sometimes the most important step in any meaningful adventure is taking the leap.

SEVEN SUMMITS

(AMERICAN STYLE!)

If you’re looking for a huge summer adventure that doesn’t involve crowds or international travel, consider climbing the highest mountain in one these seven states. Trust us, they deliver the goods.

Words KELLY BASTONE

The full splendor of California’s High Sierra is on display for those who reach the upper flanks of Mount Whitney.

Denali’s supplicants must ascend 18,000 vertical feet to reach the summit—more than on Everest.

CALIFORNIA

MOUNT WHITNEY, 14,505 FEET

Even if Whitney weren’t the highest summit in the Sierra (and the contiguous United States), it might still rank as California’s most stunning—which is saying a lot, given this state’s prodigious scenic endowment. Viewed from the Whitney Portal trailhead on the mountain’s east side, it looks like a soaring pile of granite meringue, with a deeply creased face surrounded by jagged towers that refuse to be gentled by buffing winds.

Many yearn to stand atop those spires, and because Whitney can be summited in one 10- to 12-hour day (and chased with pizza, beer and a hot shower down in Lone Pine), it attracts throngs of fit mortals. In 2019, 84,000 people applied for hiking permits, which are limited to 100 day-use and 60 overnight passes per day from May 1 to November 1. A lottery system held every winter accepts pilgrims’ preferred dates before awarding permits for the summer and fall (because hikers often hit the trail before dawn, full moons are popular). But Cris Hazzard, a SoCal local and hiking guide who blogs about his adventures at HikingGuy.com, says that hikers with flexible schedules can skip Whitney’s lottery and nab unclaimed permits through recreation.gov. His 30 visits to California’s highest summit have taken various routes—and mostly bypassed the lottery.

Hazzard has sometimes extended his trip to the top by backpacking to Trail Camp, a stark, rock-bound nest that “feels like Everest base camp because there are no trees, but there are a bunch of other people camped there, waiting to hike to the summit,” he says. Backpacking can be a good way to avoid altitude sickness (multiple nights at altitude help the body adapt to diminished oxygen), but overnight permits are

It takes time, fitness and relentless drive to reach the summit of Mount McKinley,

even harder to get. Thus Hazzard favors the two daylong routes from Whitney Portal: The 12.4-mile (round trip) Mountaineer’s Route gains the summit via a steep, talusfilled couloir requiring Class 3 scrambling, while the standard route via the Mount Whitney Trail (21.4 miles round trip) delivers superior aesthetics. Says Hazzard, “The ridgeline hike to the summit lets you look down into Sequoia National Park to see Guitar Lake and the most beautiful parts of the High Sierra.”

GEAR UP Salewa’s Wildfire Edge approach shoes ($170) feature a sticky Pomoca outsole for smearing granite on Whitney’s Mountaineer’s Route. An edging plate beneath the toes creates a stiff, secure platform on small holds, but the shoe’s flexy midfoot construction is optimized for on-trail striding. salewa.com

ALASKA

DENALI, 20,310 FEET

Perhaps Mount McKinley’s clearest peer among iconic mountains is Everest, and even that famed 29,032-foot summit sometimes seems smaller than Alaska’s loftiest perch. Better known as Denali, the mountain’s proximity to the Arctic Circle means that climbers often experience brutally cold, -40°F temperatures in April and May (prime season). And its vertical rise is greater than Everest’s: Climbers there gain 12,000 feet from valley to summit, while Denali’s supplicants must ascend 18,000 feet to reach the top. That’s big. Yet in the realm of expedition mountaineering, Denali represents a killer bargain, costing about $10,000 for a monthlong guided trip (compared to Everest’s $75,000).

But you have to be prepared to throw down much more than money, says Joe Horiskey, an RMI Expeditions

You need crampons, an ice axe and rope to climb Rainier, which is riddled with crevasses.

On summit day, climbers on Mount Rainier typically head out long before dawn and get rewarded with an incomparable sunrise.

mountaineer who helped pioneer guided Denali climbs in the 1970s. When groups fail to tag the summit (about 25 percent of RMI’s Denali bids) it’s not due to weather— though climbers routinely spend up to 12 days holed up in tents at 14,000 feet, waiting for storms to pass. Instead, the limiting factor is toughness. “What gets people is a lack of physical conditioning or mental determination,” Horiskey says. Other peaks in this story demand one hard day (or perhaps two on Rainier) but depending on the weather, Denali demands 14 to 30 of them.

The classic West Buttress route begins with a bush-plane landing on the Kahiltna Glacier, “and those views alone are worth the price of admission,” says Horiskey. Then, hikers strap on 60-pound packs and haul sleds using both snowshoes and crampons on a multiday ascent that shuttles gear up the mountain as climbers adapt to increasing altitudes. From 7,000 to 14,000 feet, Denali is a low-angle winter camping experience on glaciated terrain where hikers complete a series of back-carries designed to grow their fitness and acclimatization. Above the 14,000-foot camp, “the complexion of the trip changes dramatically,” says Horiskey, as climbers confront wilder weather and greater risk (like navigating 40-degree pitches without a fixed rope to gain the crest of the West Buttress at 16,000 feet). Summit day hardly backs off: Even without the heavy loads that burdened them earlier in the trip, climbers spend 12 to 15 hours (round trip) commuting between the 17,000-foot camp and the summit. The panoramas over Denali’s rugged flanks are incredible. But the greater reward is an uncorrupted mountaineering experience that’s increasingly difficult to achieve in today’s high-traffic terrain. “It’s such a pure summit,” says Horiskey. “It’s the last great adventure.”

GEAR UP Snuggling into a warm sleeping bag may be your only creature comfort for weeks on Denali, so make it the Feathered Friends Ptarmigan EX -25 ($779). Waterproof fabric on the collar prevents exhalation moisture from dampening the bag, and 900-fill goose down delivers intense warmth for minimum weight (just 3 lbs 12 oz for regular length).

WASHINGTON

MOUNT RAINIER, 14,410 FEET

What’s mesmerizing about Mount Rainier is its exoticism. No fewer than 25 glaciers drape across this perfect pyramid, making it look like an alien ice feature that dropped into the lush coastal conifers from outer space. It’s shockingly huge and improbably white. And climbing it demands a whole new lexicon of mountain skills: No one simply laces up their trainers and strides to the crater rim. Instead, you’ve got to don crampons, ice axe and rope while rest-stepping your way around human-swallowing chasms in the ice. It’s like climbing in Alaska—except that bagging this summit typically takes just two days. Consequently, Mount Rainier is where wannabe mountaineers cut their teeth. Guided programs often start with two days of skill-building (like learning to self-arrest with an ice axe) followed by two days up and back. May and June offer fewer crowds and crevasses but colder temperatures; midsummer attracts the most climbers but the route includes more awkward cramponning over patches of rock.

The classic Disappointment Cleaver (or DC) route from Paradise climbs and descends almost 2 vertical miles in about 30 hours. Groups first hike 4.5 miles to Camp Muir at 10,188

feet—but it’s a short sleep. Rising at 2 a.m. lets climbers kick their spikes into cold, trustworthy ice (all bets are off after the sun warms it to mush). The on-ramp into the alpine is Cowlitz Glacier, then the Muir Snowfield and Ingraham and Emmons glaciers. Slope steepness hovers between 40 and 50 degrees. Climbing in the dark offers few distractions from your ragged breathing and fatigue.

Then the rising sun promises that the summit is near, and most climbers experience an energy surge. Steam wafting from the crater vents attest to Rainier’s status as an active volcano (should it explode into eruption, its mudslides would engulf nearby cities). Wave to neighboring Mount St. Helens, Mount Baker and Mount Hood, which pierce the clouds you stand above. “There’s a lot of elation up on top,” says Peter Whittaker, who’s summited Rainier 254 times (starting at age 12). “It teaches you how to put up with being uncomfortable,” he says. And it underscores discomfort’s eventual rewards.

GEAR UP Petzl’s Glacier ice axe ($90) is perfect for climbing Mount Rainier: Its straight shaft makes it a secure handrail while rest-stepping, and its steel pick bites into the ice during self-arrest.

COLORADO

MOUNT ELBERT, 14,440 FEET

If Elbert were a comedian, it would be Rodney Dangerfield complaining, “I get no respect.” No technical skills are required to reach this skyscraping summit, so even flip-flop-shod lowlanders feel emboldened to scale its sprawling flanks. People have even mountain-biked off Elbert’s summit. Plus, the dirt road leading to the busiest north-side trailhead is smooth enough for two-wheeldrive sedans. But because 14,000-foot altitudes can trigger debilitating illness even in acclimated hikers—let alone ones that just drove in from sea level—Elbert is responsible for a shocking

Climbing Elbert from the south side is arguably more beautiful —and definitely less crowded.

Mount Elbert isn’t the toughest peak in Colorado, but it is the tallest— and the elevation needs to be taken seriously,

number of rescue incidents: In 2020, this single peak accounted for 35 percent of all search-and-rescue calls in the area (and that’s in a county filled with so many towering summits and spires that its mean elevation is a lofty 10,790 feet). “People look at 4.5 miles [one way, on the easiest route from the North Mount Elbert trailhead] and think, ‘I do that all the time,’” says local search-andrescue member Becky Young. “But altitude changes everything, from how much you need to drink to how tired you’ll feel. That makes it a little like Mount Kilimanjaro. It’s not technical, but still a challenge,” she adds.

And like Kili, Mount Elbert is worth notching, crowds be damned. When Young climbs it for fun (rather than for S.A.R. missions) she approaches from the mountain’s south side, “which is by far the most beautiful way,” she says. That route starts from Black Cloud trailhead, located near two U.S. Forest Service campgrounds (Twin Lakes and Parry Peak) that allow hikers to acclimatize with a night or more at Elbert’s base.

A predawn start is the standard—hikers should retreat below treeline before afternoon lightning storms assault the summit—and the 5 miles (one way) of good trail gains 5,250 vertical feet. The final stretch includes a mile-long ridgewalk and even a bonus summit: Hikers top out on 14,134-foot South Elbert before gaining Elbert proper. Plus, this route sees a fraction of the throngs that approach from the northeast. Says Young, “You can wave to the conga line, because mercifully, you’re not in it.”

GEAR UP Snowstorms have been known to visit Elbert even in July and August, so pack a mountain-worthy rain shell: The three-layer Patagonia Storm10 ($299) buffers wind with 100 percent recycled nylon ripstop—but weighs just 8 ounces.

The UV intensities atop Mauna Kea are among the highest on earth.

The aptly named Pearly Gates are on a more challenging route to the summit of Mount Hood.

HAWAII

MAUNA KEA, 13,803 FEET

Measuring Mauna Kea’s height from sea level, it’s an impressively tall peak: Hikers log 6 miles (one way) and gain 4,500 vertical feet from the Visitor Information Center at 9,200 feet (a road to the top also serves the Mauna Kea astronomical observatories). But as a sea volcano, Mauna Kea isn’t based on land like the other mountains profiled here. Its foot sits on the sea floor, 3.6 miles underwater—and measured from there, the mountain reaches 32,696 feet, arguably making it the tallest on earth.

To appreciate its entirety, in February 2021 adventurer Victor Vescovo piloted his submersible to the foot of Mauna Kea, 27 miles offshore. Then he and two companions paddled sea kayaks to land, bicycled 35 miles up the dormant volcano and reached the summit by foot. “She is just an immense mountain, and yet unlike the jagged Himalaya, very quiet and majestic in her form,” says Vescovo, who’s climbed the planet’s seven highest summits.

At its base, Mauna Kea appears “very different from the usual rocks and plains of other deep areas,” says Vescovo. The large slabs of pillow lava and its mounds of twisting, curving piles of basalt look “like a crazy dump of toothpaste on the bottom of the sea floor,” he says. More surprises awaited Vescovo on top, which was covered with more snow and ice than is typical for Mauna Kea. “Not exactly something one expects on a mountain in Hawaii,” notes Vescovo, who was nearly knocked down by the summit’s ferocious wind. “I was wishing for my crampons as we scaled the last hundred feet, but we were able to kick steps into the snow and ice and ... yes, it was a lot more intense, and cold, than I expected.”

Many hikers, even ones who don’t begin their journey on the sea floor, report the same surprise at discovering Mauna Kea’s wintry upper reaches, which necessitate sturdy boots, a warm jacket and ample sun protection (thanks to its lofty elevation and low latitude, Mauna Kea’s UV intensities are among the

highest recorded anywhere in the world). Colorful rocks and cinder cones turn the stark landscape into eye candy. Some of their lichens are so rare, they’re only found on Mauna Kea. And a spur trail leads to Lake Waiau, the Pacific Basin’s highest lake at 13,022 feet. These waters are sacred to native Hawaiians, as is the summit: It’s considered disrespectful to stand on the very top, where the goddess Poli‘ahu lives. Perhaps she’s responsible for stealing Vescovo’s chapeau. “Shrieking winds up top blew off my favorite hat, one I climbed Everest with,” he says. “So it seems that she demanded a special offering from me to ascend to her sacred summit. I just smiled, let her have it and kept going up.”

GEAR UP Ball caps sacrifice your ears and neck to Mauna Kea’s roasting UV index, so choose the brimmed Fjällräven Abisko Summer Hat ($55). Its chin strap keeps it leashed amidst summit gusts, and waxed poly/cotton fabric fends off wind and rain without smothering your sweat.

OREGON

MOUNT HOOD, 11,249 FEET

Like a ’68 Plymouth, Mount Hood is a badass brawler that’s short on subtlety and all about power. “It’s kind of a blue-collar mountain,” says Cliff Agocs, an AMGA Alpine Guide who coowns Timberline Mountain Guides and has summited Hood at least 100 times. “It’s like the smallest of the big mountains, so it attracts people that are delving into mountaineering for the first time, but it’s also steeper and harder than people expect.”

As with many volcanoes, Hood’s central plug of magma erodes more slowly than its flanks, so it actually grows slightly steeper over time—and currently, the summit pitches on Hood’s easiest routes measure 45 degrees. “On a snow slope, that feels pretty real,” says Agocs. Plus, Hood’s proximity to the Columbia River places it in a fire hose of weather. “That valley acts like a superhighway for moisture off the Pacific, which slams into the mountain and creates some really cold, gnarly storms,” Agocs explains. Hood’s trademark is rime ice: Climbers often get coated with sparkly crystals that encase them in a glittery white shell. Then, once they penetrate the cloud layer at 9,000 to 10,000 feet, they’re treated to a sunrise panorama that bests anything one might glimpse from an airplane window: The mountain rises alone above a heavenly blanket of fluffy batting.

Hood’s prime climbing season typically runs from mid-May through mid-July, after the avalanche danger has quieted but before melting snow makes rockfall routine. The classic Hogsback route up the peak’s south side spans 7 miles (one way) and 5,290 vertical feet; a midnight start is de rigueur. You’ll want an ice axe, crampons and rope (and the skills to use them), plus a self-issued permit (available for free at the Wy’East Timberline Day Lodge). First-timers will find the southside route to be spicy enough, but repeat offenders with iceclimbing savvy may want to explore Agocs’ favorite springtime route up the Eliot Headwall on Hood’s north side. “There’s some really beautiful ice, about 150 feet tall, before you get to the mountain’s north ridge,” he says. “And the fun part is popping onto the summit and surprising everyone there from a direction that nobody expects.”

GEAR UP Microspikes provide inadequate purchase on the veins of hard ice that hikers typically encounter on Hood’s Hogsback route, so strap on Black Diamond’s stainless steel Sabretooth Crampons ($190), with front points that bite into steep, slick slopes.

NEW HAMPSHIRE

MOUNT WASHINGTON, 6,288 FEET

The Northeast’s highest peak may be shorter than Western allstars, but it’s still a spanker—in part because it’s so mercurial. “On its calmer days it can be very alluring and sucks you in, then punches you in the head,” says local hiking guide Steve Dupuis. He’s summited Mount Washington in all seasons and shades of weather, along with all the White Mountain peaks exceeding 4,000 feet in elevation. But Washington’s the one “with an attitude,” says Dupuis. That’s because it claims more abovetreeline terrain than its neighbors, with about 2,000 vertical feet between the krummholz and the summit. Those vast barrens get slammed with some unique weather wizardry: On its summit, storms tracking east collide with northbound systems out of the south, and Washington’s funnel-shaped west side intensifies the battle by accelerating the wind. For decades, Mount Washington held the world record for fastest surface wind ever recorded (a neck-snapping 231 miles per hour). That’s big-league stuff.

The shortest and easiest route to the summit climbs through Tuckerman Ravine, where backcountry skiers come from April to June to carve their signatures on 40-to-60-degree snow slopes. June through October, hikers begin at the Pinkham Notch Visitor Center in Gorham to hike 4.2 miles and gain 4,300 feet to the summit. “That 4.2 miles is a massive void you’re crossing,” says Dupuis, noting that the valley generally enjoys flip-flop weather while the talus slopes see cold, wet wind for about 300 days a year. But on those 65 clear days? Hikers see a panoply of peaks, including New York’s high peak, Mount Marcy, 134 miles away.

Once you’ve completed the classic route, consider tackling one of the innumerable variations on the Mount Washington summit theme—including Dupuis’ favorite route up the west side via the Ammonoosuc Ravine Trail (parking permit $5/day). That path parallels a series of waterfalls before leaving the trees near the Appalachian Mountain Club’s Lakes of the Clouds Hut (where hut keepers sell scrumptious baked goods). From there, it’s 1.4 above-treeline miles to the top of Washington. Craving even more? The Presidential Traverse links Washington with seven other mighty summits on a 22-mile point-to-point that’s mostly above treeline. Dupuis has completed more than 100 of them—and notched 30 Prezis in winter, when the weather observatory on Mount Washington’s summit routinely records temperatures of -35 degrees.

GEAR UP Ward off wintry weather—experienced year-round on Mount Washington—with the Mountain Hardwear Ghost Whisperer UL Jacket ($375). It packs to softball-size and weighs less than 7 ounces, yet delivers whopping warmth thanks to 1,000-fill, certified-responsible down.

Full Circle In Chilean Patagonia, four adventurers follow in the footsteps of their heroes as they attempt a rare ski descent of a volcano surrounded by savage jungle. A new self-produced short film documents their quest for the purest of climbs.

Words NORA O’DONNELL Photography ERICH ROEPKE, STEIN RETZLAFF and THOR RETZLAFF

October 23, 2019: Ski mountaineer Stein Retzlaff descends Corcovado, a volcano in the Andes of Chile about 800 miles south of Santiago. A dense jungle surrounds the volcano before meeting the Gulf of Corcovado below.

I

n life, there are the journeys that define you—the ones that build your character or give you a spiritual sense of purpose. When Yvon Chouinard and Douglas Tompkins drove a Ford Econoline van from Ventura, California, to Patagonia in 1968, it set the course for what they would do later in life: Chouinard founded the outdoor company Patagonia, and Tompkins co-founded The North Face. Both men became revered environmentalists and conservationists. But back in those early days, they were just two dirtbag adventurers eager to explore the wilds of South America.

Decades later, Jeff Johnson found the 16 mm footage of that 1968 trip and was inspired to follow in the footsteps of his heroes with a journey of his own, traveling from Mexico to Chile by boat. That six-month expedition ultimately became the subject of the 2010 documentary 180° South: Conquerors of the Useless.

Johnson was Patagonia’s first official staff photographer, and Chouinard had given him a tattered snapshot that Tompkins had taken of Corcovado, a majestic, snowcapped volcano surrounded by a nearly impenetrable jungle. Climbing Corcovado—a remote peak summitted only by Tompkins at that point— became the final leg of Johnson’s journey.

Chouinard, along with rock climber Timmy O’Neill and Rapa Nui native Makohe, joined Johnson on the climb. (Serving as their cameraman was the future Oscar-winning director of Free Solo, Jimmy Chin.) But at the time of their ascent it was summer in Chile, and the top of Corcovado was covered with dangerously loose rock that kept the team from reaching the top.

“The rock was like kitty litter,” Johnson says over the phone more than 10 years later, while on a drive from his home in Santa Barbara to Yosemite. If there had been snow, Johnson explains, reaching the summit might have been possible, but without it, the climb wasn’t worth risking his life.

“But the real difficulty of the climb is in the jungle,” Johnson says. In that region of Chilean Patagonia, there are many summits that remain unclaimed because they are protected by a jungle so dense that intrepid climbers can’t discern treetops from the ground below.

Clockwise from top left: Erich Roepke, Stein Retzlaff, Rafael Pease and Thor Retzlaff follow in the footsteps of Chouinard, Tompkins and Johnson by attempting the first human-powered ski descent of Corcovado.

Roepke, Pease and the Retzlaff brothers arrive at the beach near Corcovado with the help of two local fishermen. The boat trip took four hours.

When 180° South was released in 2010, it made a lasting impression on Erich Roepke, then an athletic and outdoorsy 17-year-old growing up in Northwest Oregon. “I remember seeing them struggle on camera for the first time and thinking, wow, this is a real adventure,” Roepke recalls. He was also moved by something Chouinard said in the film: “For me, adventure is when everything goes wrong—that’s when the adventure starts.”

A year earlier, Roepke had been backcountry skiing with his father and a family friend when they were caught in an avalanche. His father didn’t survive. It’s a moment in his personal history that Roepke openly acknowledges but isn’t ready to discuss. But he adds, “It stopped me from backcountry skiing for a while.”

While attending Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Roepke gained a lifelong friend upon meeting Stein Retzlaff, a Truckee, California, native with a voracious appetite for exploring the wilderness and a love of skiing in his DNA. Retzlaff encouraged Roepke to pick up backcountry skiing again, and together they started taking trips abroad. The enterprising duo even convinced Lewis & Clark’s finance committee to fund their spring break trip to Antarctica, which comically ended in Chile when they ran out of money and inclement weather kept them from hopping on the last flight of the season. “But we ended up going to Patagonia instead,” Roepke says.

There’s never one direct path to becoming professional adventurers—or full-time “dirtbags”—but the 27-year-old Roepke and 26-year-old Retzlaff are already embodying the mantras of their heroes. These days, Roepke travels around the world as a cameraman for various adventure projects, and Retzlaff has supported famed polar explorers Mike Horn and Børge Ousland on expeditions in the Arctic and Antarctic.

But their most ambitious adventure to date was inspired by the legacies of Johnson, Chouinard and Tompkins: In October 2019, they decided to attempt the first humanpowered ski descent of Corcovado and film it—without a support crew.

They did, however, bring some legitimate dirtbags along for the ride. Retzlaff was coming off an expedition with Horn and Ousland when he got the call from Roepke about Corcovado. Without hesitation, Retzlaff immediately flew home to Truckee to pick up his gear and his younger brother Thor, who’s well versed in the kind of Type 2 fun that the average person might find preposterous and excruciating. Roepke was already in Patagonia, having achieved the

On the first night of their expedition, the four men witnessed a perfect sunset before camping under the stars. At midnight they awoke to pouring rain and quickly set up tents.

Erich Roepke wields a Tramontina machete. In Santiago, the group visited about 15 different stores in search of blades for the jungle. “Erich picked the best one,” Stein Retzlaff says. “The rest barely broke branches.”

The team followed a small river as their main path to the volcano, though they tried to take a shortcut through the jungle. “It was far too dense and would have required three to four extra days’ worth of food,” Roepke says.

first ski descent of Tupungato, a 21,560-foot volcano on the border of Chile and Argentina, with Chilean snowboarding mountaineer and filmmaker Rafael Pease.

In fact, it was Pease who jogged Roepke’s memory of watching 180° South and inspired the idea of going to Corcovado. Pease, an accomplished backcountry snowboarder, had attempted the first ski descent of the elusive volcano in 2017, but he couldn’t make it through the jungle and had to turn back. “It was brutal,” Pease says. “Type 3 fun for sure, which is best enjoyed once you are home.”

The group took just two weeks to prepare, quickly assembling a mishmash of gear for an expedition of seemingly endless ecotones and disciplines—ocean, beach, jungle, canyoneering, ski mountaineering and ice climbing. And since they were their own filming crew, they packed four cameras (and lenses), solar panels, battery arrays and drones. Each climber was carrying more than 100 pounds on his back. “It was completely ridiculous, just out-of-this-world heavy,” Roepke says.

“We didn’t have sponsors,” Retzlaff adds. “We’re wearing the biggest hodgepodge of equipment, just scrounging up whatever we could to make it work.”

Once they arrived in Santiago, they spent 12 hours driving around trying to find machetes. Only Roepke had the foresight to purchase a name-brand blade instead of a cooler-looking knockoff, which the others would come to regret.

From Santiago, they drove more than 800 miles south to Corcovado National Park, took an overnight ferry and then hired two

Snag city

“We knew the jungle would be rugged to navigate,” says Thor Retzlaff, 25, pictured with Stein. “We were getting caught up on just about everything. Our pace was unimaginably slow.”

“Our blades dulled, making the effort exhausting,” says Stein Retzlaff. “We resorted to pushing our bodies through slimy branches and dark jungle bogs.”

“I have learned to adapt my expeditions to their own surroundings,” says Pease, 26, who is using nalca leaves as rain protection. “The stalks are edible and delicious.”

As the others pushed ahead, Thor stayed behind to film them by drone. When he caught up, “Erich captured the agony of my repositioning three bags and skis,” says Thor (above).

local fishermen to take them to the shore below the mountain. They arrived at the rocky beach near the volcano at sunset, the air a mild 65 degrees. “I’ve never been to a place that beautiful that felt so wild,” Roepke says. That first night, they decided to sleep out in the open air and take in the scenery.

But then the rain hit in the middle of the night. Roepke awoke with a start and saw his tent sprawled out and covered in sand. Retzlaff, who didn’t have a waterproof bivy sack for his sleeping bag, was rolled up on the ground in an oversized garbage bag. They quickly set up tents, but their gear was already soaked.

“It was so uncomfortable,” Retzlaff says. “Our shoes never dried the entire trip. Every morning you’d have one extra sock, but you’d slide it into a squishy cold boot.”

The next day, they soldiered up the river draw for about a mile, but the rain turned into a downpour. Setting up a tent was pointless; the water would wash it away. “We’re in complete disaster mode, borderline hypothermia,” Roepke says. To get warm, they huddled against a cliff, constructed a makeshift shelter out of giant nalca (Chilean rhubarb) leaves and built a small fire.

Retzlaff’s eyes teared from the smoke, his hands bled, insects nipped at his neck and a fountain of snot poured from his nose.

Roepke turned on his camera, and the two friends started laughing. They were living the kind of struggle they saw in 180° South—and loving it.

“We weren’t missing out on that struggle at all,” Roepke says. “But we don’t get down. It’s hard to be miserable when you’re cracking up at how miserable Stein looks. Once you have someone else to laugh who’s equally messed up, you can’t be angry.”

“You already expect it’s going to be super shitty and not rainbows and sunshine the whole time,” Retzlaff adds. “We took off all of our clothes except our rain jackets. We’re butt naked underneath, just skipping around and chopping down wood to build a fire and having the most fun.”

As they crept deeper into the jungle, the off-brand machetes barely cut through branches. They fell neck-deep into bogs filled with leeches and clambered over trees, not aware they had climbed them until they were on top of the canopy. Their average speed was about 100 meters per hour.

“It’s the most horrible part,” Johnson recalls of his own journey through the jungle. “We were so exhausted. Even with a normal pack, it’s snagging on everything. It’s character building—going all day just on the verge of snapping because it’s so frustrating. And these guys had skis on their packs!”

After three long days, the four climbers reached the snow line. They had traveled only 4.5 miles. Once on snow, the ascent was more manageable, but when the terrain switched to ice and the morning stretched into the afternoon, things became shaky. “The ice around us was melting out so fast that we couldn’t hammer in our ice screws,” Roepke says. They kept going but eventually reached a point where proceeding—up another pitch at 90 degrees—felt too risky.

They decided to turn around about 100 meters from the summit, at almost the exact point Johnson had turned around more than a decade ago. “I was disappointed,” Roepke says, “but it never registered that we fucked up. We set out to explore and realized it was way harder than we expected. Whenever something like this happens, you have to redirect—and then we’ll become equally stoked by that two seconds later.”

So they did. The skiing was spectacular, with amazing afternoon sunshine and spring corn snow. They paid homage to their heroes, gained a deeper respect for the landscape and became even more intertwined as a family of friends.

“It’s kind of like the quest for the Holy Grail,” Chouinard says at the end of 180° South. “Who gives a shit what the Holy Grail is—the quest is what’s important. The transformation is within yourself.”

Johnson knows this, too. “These guys are true adventurers,” he says. “They are just going for it, but they’re smart. If they don’t make it, it’s not the end of the world. That’s what’s so special about what they did. The spirit of it was really pure. That’s what true climbing is.”

A year and a half later, the Corcovado crew have released two separate short films, each using different footage from the expedition. Pease created an artful ode to the overwhelming power of Mother Nature titled Korovadu, the volcano’s name by the Indigenous Mapuche people. “It’s a wild place that needs to be protected,” Pease says. “If people decide to go into Patagonia, they must go with respect, knowledge and care.”

With his film, Roepke took a more personal approach by paying tribute to Johnson and 180° South for inspiring his entire way of life, much in the way Chouinard and Tompkins had inspired Johnson. “It was the most rewarding expedition I’ve done so far,” Roepke says. He titled the film Full Circle.

Once we saw the snow line, we were stoked,” says Stein. “It was a relief to drop my other gear,” Thor adds. “I thrive in the snow, too.”

Thor Retzlaff does his final rappel off of Corcovado, heading down to his skis. “It was a miracle the weather broke for us on that day,” says Stein. But the melting ice kept the team from reaching the summit by a mere 100 meters.

Flying high

Thor Retzlaff records the team by drone, just below the summit. “This shot captures the bountiful inconvenience of adventure and the blessings of failure,” he says. The short film of their journey, Full Circle, is now available on YouTube.

HIDDEN DEPTHS

Exploring narrow, unmapped underwater caves deep in the Mexican jungle is fraught with danger. But for two of the world’s most intrepid cave divers, what they discover in these unexplored passageways can be truly life-changing.

Words KLAUS THYMANN and RUTH McLEOD Photography KLAUS THYMANN

Klaus Thymann enters the water of the cave—colored yellow near the surface by tannic acid from recent rainfall—with his camera, watching closely for any sign that the underwater housing is leaking. A video light illuminates the path ahead, along with a light on his helmet, which he calls his “third hand.”

K

laus Thymann is 1,000 feet inside an underwater cave in Mexico, 30 feet below dense jungle, navigating a constricted passageway that’s barely bigger than he is—around 2 feet from floor to ceiling. The Danish-born photographer and cave diver is shooting what are likely to be prehistoric human bones, so he has had to adopt a plank position with his arms outstretched, using his lungs to control his level in the water; if any part of him touches any surface, he could destroy these artifacts by disturbing silt that could also leave him with zero visibility. Under this intense pressure, Thymann— who estimates he has spent several hundred hours in caves like these during his career—is the most stressed out he’s ever been on a dive. But he knows that if he’s unable to stay calm, he’ll get through his supply of air too quickly and there’s a high chance he could drown.

This is cave diving at its most extreme. Cave exploration is a better description, since most of the routes Thymann and his diving partner, Alessandro “Alex” Reato, survey have not yet been mapped, making the pair the first humans in modern history to lay eyes on whatever awaits them around the next dark corner. “Your body screams panic in these situations,” says Thymann. “You are underwater, in darkness, in a confined space, so stress levels are high. But your survival depends on your being calm. You have to develop the skills to subdue that intuitive fear.”

Squeezing expertly through spaces small enough to make most wince, these underwater explorers are willing to go where most can’t or won’t, carrying with them all the equipment they need to avert disaster if something goes wrong —and things often do. “It’s not really a question of if but when something will go wrong, meaning you just have to be prepared for it,” says Thymann. “There is no dive buddy. I frequently squeeze through gaps so small I have to tilt my head sideways, and in that position another diver can’t get to you.

“When it comes to gear, we have at least two of almost everything. Two is one, one is none, as we say. Packing and preparation are done with military precision, as even a little thing can be what saves the day. I don’t like risks. I work methodically and don’t deviate from my protocol; this is how I justify doing this. I plan, I prepare, and then of course I’ve had extensive professional training and

Top left: You can’t see it from the air, but beneath the dense jungle there’s access to the underwater caves. Above: They may be filled with air, but the dive tanks top 20 pounds each, meaning they must be ferried to the site one at a time.

Locating the cave

“We start out with our porter, Jesus, walking in front of the 4x4, chopping at vegetation with his machete, but at some point the road and jungle merge, so we get out and walk. Alex’s Italian arms get excited as he talks, disturbing a hornet nest. We run but still get stung. We’re heading for the GPS coordinates that mark the position of a cenote—our access point to the underwater river system. We find cenotes from our Mayan contacts; from seeing on a map where the water should go; from diving and seeing light above; and from others who have told Alex they’ve found a hole in the jungle.”

Time travel

“I’ve been cave diving for less than 10 years, but I’ve dived all my life. I remember freediving as a kid, going down with a net to catch octopus in the Mediterranean. I like the challenge of cave diving; I like doing things that are complicated and haven’t been done before. Once I enter the rabbit hole, I just want to go further into it. Diving the underwater rivers feels like entering a time capsule; time doesn’t exist, as there are no outside factors to disturb you—no daylight, no noise, just the sound of your breathing. As we swim through the water, we enter an ancient time, experiencing what no one has for hundreds and thousands of years. However, diving is also very much about time—you have to keep track of it to survive and know your limitations.”

Above left: Thymann—providing the only light in the pitch-black cave—follows the navigational line. The scenery changes constantly: “Two kicks of your fins and you’re somewhere that looks totally different.” Right: Reato readies his mask for diving.

have built up experience. It helps that my personality is über-rational, so I generally solve issues well under pressure—be that on a mountain, inside a glacier, deep underwater or on the edge of a volcano.”

During a varied career as a journalist, photographer and explorer, London-based Thymann, 46, has trekked new routes to explore the glaciers of Uganda and Congo; was the first person to scuba-dive the world’s clearest lake, New Zealand’s Blue Lake; and has led expeditions to mountains on six continents, all with the aim of furthering knowledge and awareness of the climate crisis. And this mission, he says, is similarly important: “It’s an expedition with a purpose and that’s what I find interesting. I need that purpose. All of the peaks have been summited, so now you get things being done in multiples—the Three Peaks Challenge or whatever—an artificial goal in order to set a new record. I have a lot of respect for people who are able to do it, but there is no benefit to the world of the 100th person standing on top of a mountain. I’m trying to come back with something that benefits science and helps us make informed choices about how we behave on this planet.”

It was in Mexico—Reato’s current home —that Thymann first met the Italian cave diver and former army cartographer, through friends, in 2016. The pair soon realized they shared a love of mapping and heading off the beaten track; Reato had explored more than 40 miles of the country’s caves. “I have a similar appetite to Alex in terms of going places where others don’t,” says Thymann. “Even most people who enjoy cave diving won’t crawl down a piece of rope into a hole in the jungle they can barely squeeze through, having walked for miles through dense jungle. But we like the parts that are still really wild, and to get to that frontier you must engage with nature differently. Exploration cave diving certainly isn’t for everyone—our sort of cave diving takes claustrophobia to a new level. With Alex, I feel that I’ve found a partner in crime.”

So when Reato contacted Thymann last year to tell him about his discovery of this ancient skeleton, the Dane was all in. “In this case, if it wasn’t the bones and the fascinating insights into the past they might give us, it could be for an environmental purpose, like trying to map underground rivers to help protect them,” says Thymann. “The caves here in Mexico are unique; they’re the world’s largest underground system and we need to preserve them—for the habitat, for the reef, for what it provides, and just because it’s a huge archaeological site.”

Using calculations based on historic water levels, they know the bones could

be more than 9,000 years old, which would make them some of the oldest ever discovered in the country. And the race was on to document the find and collect a sample for analysis, guaranteeing the bones official protection from looters who plunder sites such as these.

“We knew we had to keep the exact location of the bones to ourselves,” says Thymann. “What has happened in the past is there’s been an archaeological find, but then you can’t surround it in barbed wire, and when people have come back it’s gone. To me, it’s such a weird thing. I don’t understand it. Even though it’s probably a very small minority doing the looting, they pose a disproportionately big risk. It happens all over the world; there’s a black market for artifacts. So we knew we had to be careful—and quick.”

Thymann doesn’t drink any alcohol for at least a week before a dive. He exercises every day and sticks to a healthy diet—extra pounds do nothing for your ability to inch through cramped spaces. “For weeks, I prepared from my base in Europe. For an expedition, I bring more than 100 items. I keep things in working order, but I still test it all before heading out. Alex sent me a sketch of the area with the bones and we discussed approaches. We have defined roles: Alex leads the exploration and I document it and create the material the archaeologists and scientists need.”

When Thymann arrived in Tulum to meet Reato and head into the jungle, he was—as always—prepared for anything. But no matter how many times he ventures into the depths of the Yucatán underwater caves, it never becomes routine. “Before heading into the cave, I felt a mixture of extreme excitement but also disbelief,” Thymann says. “I was thinking, ‘These are prehistoric human bones and this is insanely special.’ There is awe around it. It makes you humble in a way. You’re just looking at a tiny piece of a very big puzzle. And that’s a very healthy way of looking at things sometimes. It reminds you that your little life is not so significant.”

Gear list

Preparation is key, and a mission of this kind requires 100 lbs of vital equipment.

1. Two independent tanks with a regulator and pressure gauge attached 2. Fins. Thymann uses normal fins, which are slightly longer and heavier than cave fins and help counterbalance the weight of his camera 3. Wetsuit. He has a 5 mm suit, hood, 3 mm vest and boots 4. Secondary dive light (first backup), which is attached to his helmet with a bungee cord 5. Helmet, which is customized to hold lights 6. BCD (buoyancy control device) with two bladders—the second is a backup 7. Primary light, attached to a battery with a cable 8. Video lights 9. Line markers, used for navigation. Thymann’s are bespoke, circular “cookie”-shaped markers, so on wellused lines he can feel which are his 10. Third light (second backup) 11. Dive pouch, which holds tools and spare parts, reels and a spare mask for deeper dives 12. Camera housing with dome and handle 13. Underwater flashes 14. Dive mask 15. Bottom timer, which displays depth and time (backup to dive computer) 16. Camera housing for a small compact camera (mainly backup) 17. Surface marker, which can be inflated at the surface entry point with a line attached, or, once submerged, float camera housing to the surface quickly in case of an issue 18. Primary reel 19. Dive computer 20. Wrist slate, used for navigation 21. Bigger slate and pencil (with wrist strap), used for advanced notes

2 3 4 5

9

1 6 7

8

10 11

14

18

19 12

15 16

20 17 13

21

Fully equipped

“When cave diving, everything’s complicated. Communication underwater is complicated, because you can’t talk, so you use sign language. But then a lot of time in caves you can’t see, either, so you communicate with light signals. Then, if we’re doing something that involves a fairly complex task, we use a slate that we can write on with a pencil. Cave diving in itself is taxing; the basics you have to monitor are time, depth, gas consumption and navigation. Then adding something else complex, like doing photogrammetry [surveying and mapping] or photography underwater, is extremely difficult. I have to know where every piece of gear is, by feel, so I can reach it in zero visibility if I need to, and know how to instantly unclip and untangle it. For instance, my pencil has a bungee cord that sits around my wrist like a bracelet. If I’m writing, that’s a tool I might need for the recalculation of gases, and for navigation, too, so that pencil is insanely important. But then I do have a spare pencil in my pouch. And I carry a knife to sharpen it underwater if I need to.”

“Having swum hundreds of meters into the cave, I’m in an appendix section of it, hovering above prehistoric bones. The space is so tight there’s less than an elbow’s length between the dome on my underwater-camera housing and skull parts, including loose teeth that lie beneath the fine-grained silt. Any wrong move will disturb this archaeological site and cause damage. It’ll also cause a silt cloud to rise, creating zero visibility, which is a really bad scenario. There’s so little room I can’t even swim, so I’m planking, stretching out my body, arms and legs. I’m being positioned by Alex, who’s holding me by the ankles and maneuvering me around. To navigate, I signal using my hands—index finger forward and Alex slowly pushes me forward. As I try to remain zen in this cavediving yoga position, Alex hits the top of my leg. We’ve rehearsed this and I know what to do. I release a tiny bit of air from my lungs and descend about 5 centimeters, just enough to avoid a lowhanging part of the cave roof. Every small movement here is a feat in itself. We move a few centimeters at a time, across an imaginary grid, to document everything. I check my pressure gauges constantly to ensure I’m not using too much air and that I can still get out of here. The whole operation takes 70 minutes. I shoot about 500 images of the area where the skull is, which will be put into a photogrammetry model so scientists can navigate the cave on a computer screen.”

Bubbles created by the divers accumulate and merge at the roof of the cave. Here, it’s essential they don’t come into contact with the porous cast rock that surrounds them; even a small impact will cause damage.

Reato lays down a fresh navigational line from his exploration reel in this unexplored cave and ties it off to a stalagmite.

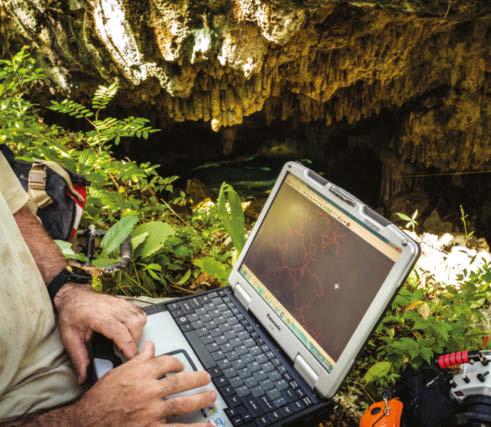

Off the chart

“Mapping is a big part of what I do. Whether it’s mapping glaciers or new trekking routes in Uganda, I try to map out new terrain, both in a conceptual and very straightforward, practical manner, and these underground river systems are one of the only places on the planet that hasn’t been mapped. That makes it very exciting. There are many risks— the equipment can fail, the cave can collapse, you can have a heart attack underwater or get lost in a cloud of silt—but the reality is that most deaths while cave diving happen due to navigational errors. Cave diving follows a tried-and-tested method of having a string to follow out, but the caves are not simple one-lane roads; they’re more like distorted spiderwebs. One wrong turn can lead you further away from the open water, and at some point you run out of air.”

Thymann uses UV light to assess damage to the bones. Below: Close to an intact jawbone lies a molar with good potential for DNA extraction.

Body of evidence

“There are lots of indications that this is a prehistoric skeleton. For now, that’s based on the historic water levels and the current water depth. By combining the two measurements, you can see what’s realistic. The depth of the site is 10 meters [33 feet], which means that the last time the caves were dry in this area was between 8,000 and 10,000 years ago. And it’s totally unreasonable to think somebody could have died and floated into these caves against the current. So it makes these bones potentially some of the oldest human remains to be found in Mexico. But that will depend on the exact date. The water-level calculations indicate the youngest the bones should be, but of course there’s nothing to say these bones couldn’t have been here for a significant period before the water level rose. For now, having completed this part of the mission, we head out and surface. It’s a success, and we have all the material we need to file permits with the Mexican authorities that allow us to take a sample for analysis. The DNA can reveal fascinating insights into our ancestors and underline the huge archaeological value of these river systems.”

HAND-BUILT FRAMES

Jean-Baptiste Liautard takes bike photos that are one of a kind. A 2019 winner of Red Bull Illume, an international photography contest for adventure and action sports, he elevates mountain-bike photos to a fne art, imbuing images with poetry and mystery. Here, in his own words, the French photographer explains his craft and the behind-the-scenes work that helps him get the images he wants.

Words PATRICIA OUDIT Photography JB LIAUTARD

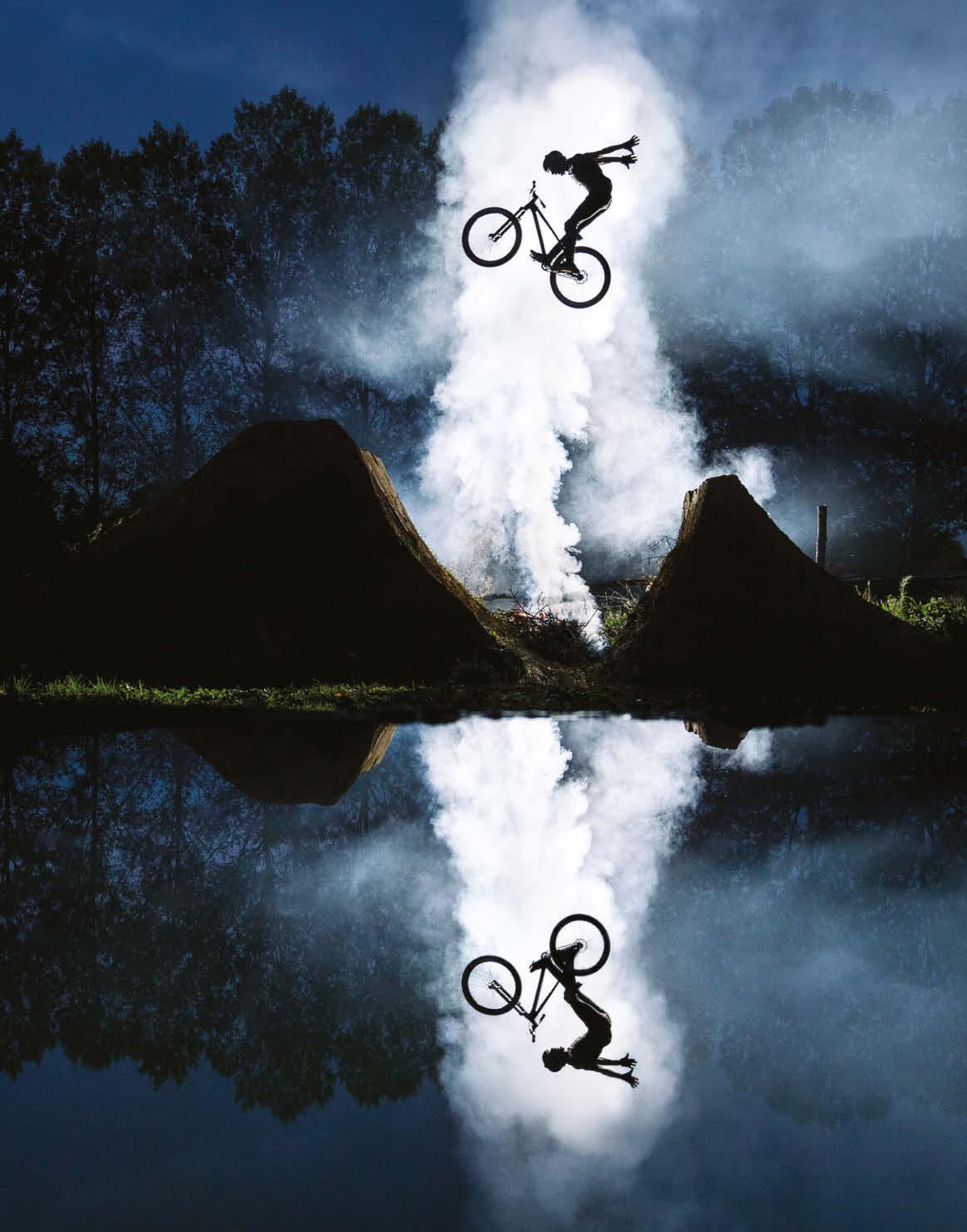

Extraterrestrial

The image that took the top spot in Red Bull Illume 2019 has all the magic of a scene from E.T. The secret? “I filled a wheelbarrow with water and then shot into the reflection,” explains Liautard, 25.

Jean-Baptiste

Liautard turned to photography after a bad bike crash— which sidelined him from the sport he had loved since he was 13. A broken shoulder set him on a new path—one that would become his passion: “I started shooting with GoPros and bought my first camera when I was 18.” Liautard took hundreds of photos of his riding friends while he was studying for a degree in photography—and then clinched his first contracts with cycling magazines and bike brands after graduating. When asked to name his favorite locations to shoot, he singles out two—British Columbia, with its forests wreathed in mist, and the deserts and strange rock formations of Utah. His photographs stand out for their unexpected elements and his signature artistic approach. “Taking a beautiful cycling image takes creativity, time and planning, especially for the jumps,” he says, going on to explain his obsessive attention to detail. “I’ve often spent 10 minutes placing a branch in a particular spot.” Such meticulous preparations, where the rider is an equal partner in a demanding and rigorous process, are not easy—but they yield magnificent results.

jbliautard.com

Dropping in

“I love working with the particles in the air,” says Liautard. “There’s nothing contrived in this image: All these tiny specks—like a curtain around the rider— are raindrops. In these kinds of shots, nothing is calculated. I have to react in the moment. And I often only get one chance to nail the image.” Liautard notes that shooting at night isn’t just tough for him; the rider also has to contend with the conditions. “And that’s another factor to manage— allowing the athlete to give their best without injuring themselves.”

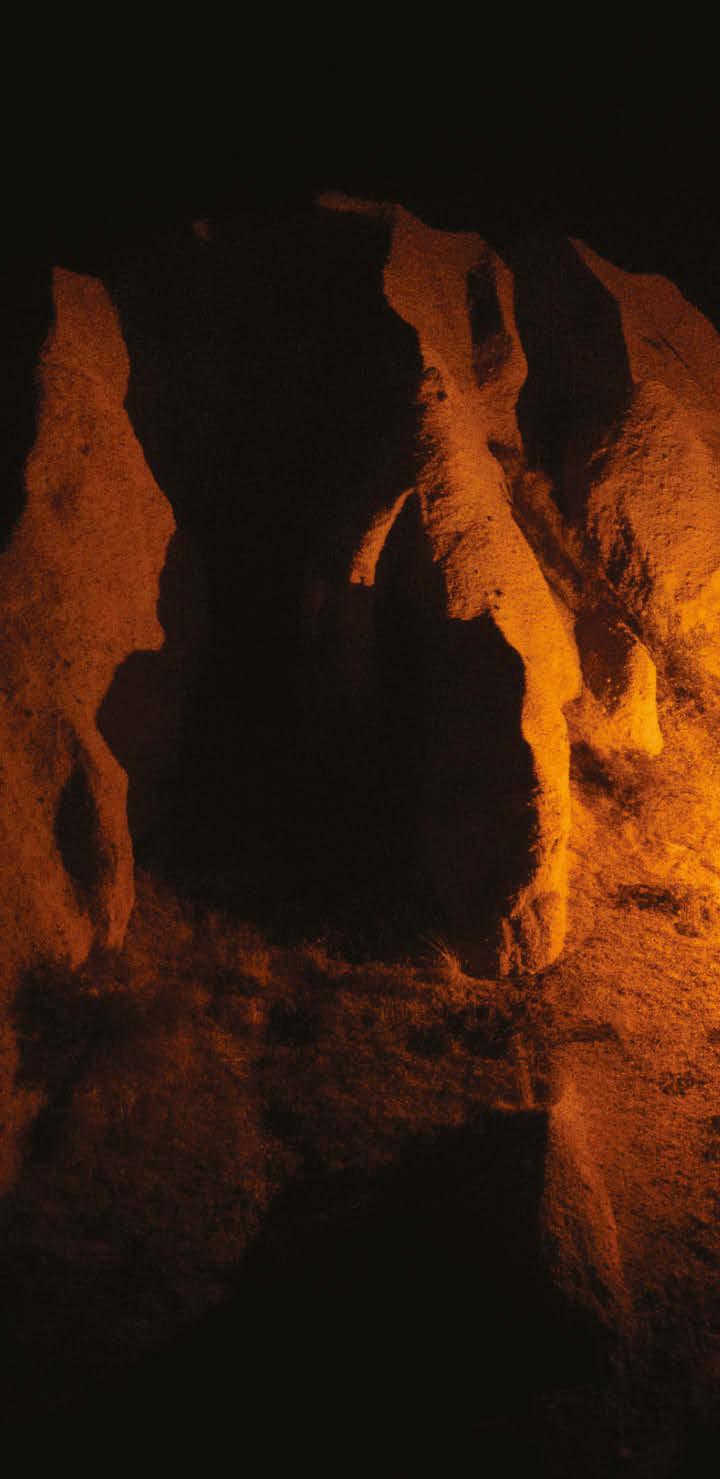

Flash dance

All these images required lighting magic of one sort or another. Says Liautard: “On the top left I used a long exposure and an LED strip to capture the silhouetted image of Thomas Genon. For the image on the top right, of Paul Couderc spraying down his ride, I put orange gel on the flashes to get this texture. The image on the bottom left is from last summer, with Kilian Bron at Lake Salagou in southern France. Here I put a flash on a drone (the same as for the photo on the bottom right, taken in Cappadocia). I was on my own, which meant I had my camera in one hand and a phone controlling the drone in the other. During the last shot the drone was almost out of battery and it started beeping, but Kilian caught it before it crashed!”

Very bright idea

Nailing the money shot (at right) in Cappadocia took time and risk. Says Liautard: “We had a racing-drone pilot with us and we put a lit distress flare on the drone [see above]. We had to light the mountain with a headlamp for the drone to take off and follow rider Kilian Bron. The ball of fire you see in the back is the light from the distress flare. Since my lighting depended on the drone, I pushed my camera in its wake. It’s not easy for the rider either, as he was in a gully moving from shade, where he’s riding blind, to light. Kilian could have fallen if the drone was late on the turn. And to ratchet up the risk, embers were flying off the drone, which meant we had to put out several sparks!”

YOU DON’T JUST NEED A VACATION. YOU NEED AN RV.

GO ON A REAL VACATION