25 minute read

Extreme E

environmental projects at each destination. And it aims to be totally carbon-neutral by the end of 2021. The concept is seen by sponsors and host countries as a win-win; governments have welcomed it with open arms. “It’s green, you promote their country for tourism, and it also gives a good image,” says Agag. “For a politician, it’s a no-brainer.”

He’s speaking from experience: the suave and savvy 50-year-old Spanish businessman enjoyed a promising career in politics before becoming a major player in motor racing. It’s an unlikely backstory for an environmental champion, but, as the founder of electric streetracing series Formula E, Agag has done plenty to wean motorsports off fossil fuels and into eco-rehab. This commitment to leaving no damage in its wake means Extreme E will have no ticket-buying spectators, but its impact will be felt. Media buzz was already growing when, in September, Formula One megastar Lewis Hamilton announced his own team and it went stratospheric.

Make no mistake, Extreme E will be very big indeed.

If you’re serious about making a splash as a green A-lister, you need your own boat. Jacques Cousteau had the Calypso. Greta Thunberg has her zerocarbon yacht. Conservation organisations Greenpeace and Sea Shepherd boast entire fleets. Agag has a 30-year-old former Royal Mail ship upcycled into a ‘floating paddock’. Cars aren’t airfreighted to races but transported inside the 6,767-tonne RMS St Helena.

Agag scrolls through his phone to show The Red Bulletin a picture of the vessel after her multimillion-pound refurb, sporting a new black, white and green paint job. He’s particularly pleased with the slogan across the hull: “Not electric… yet!” The engines have been converted to run on low-sulphur marine diesel, cleaner than the heavy diesel (basically crude oil) commonly used in shipping. RMS St Helena can cruise on one engine to lower fuel consumption and emissions, and, says Agag, will one day run on biofuel. Travelling by sea rather than air generates a third of the carbon emissions, but what happens as this ship sails is more amazing still.

In steel shipping containers onboard are hydrogen fuel-cell generators – portable emission-free power sources that can charge the cars either at sea or at the race site. “Green hydrogen is produced by solar panels or wind, depending on location,” explains Agag. “We’ll prove you can power remote areas with clean energy.” He hopes this offgrid technology might one day supply emergency power to disaster zones.

RMS St Helena sleeps 110 in 62 cabins, and her 20m swimming pool has been stripped out to make space for a science lab inspired by Cousteau’s Calypso. This is not just for show – Extreme E has also employed a committee of climate experts to provide education and research. Since her 18-month refit in Liverpool, the ship has been in strict quarantine. After virus outbreaks obliterated the cruise industry, Agag is not taking any chances – a stowaway microbe could scuttle the entire adventure.

Organising a global racing series of this magnitude was never going to be easy, but doing it during a pandemic was a huge undertaking – an ever-changing obstacle course of travel restrictions, border closures and COVID testing. “It’s been challenging,” admits Agag. “Like walking with a 100-kilo backpack. But soon the backpack will drop.”

And yet, even as the world ground to a standstill, his big idea gained traction. Motorsports aristocracy wanted in. Alongside newly knighted seven-time champion Lewis Hamilton, F1’s Nico Rosberg and Jenson Button have their own teams, while Red Bull Racing’s engineering guru Adrian Newey oversees another. From rallying, the roster includes two-time world champion Carlos Sainz, and Sébastien Loeb, the sport’s most successful-ever driver.

“They were waiting for this opportunity, hoping for off-road to become an actor in the climate action we need,” says Agag. That opportunity has finally arrived at MotorLand as they get to test their cars for the first time: “Today, we see an idea become reality.”

All 10 teams have the same car: the Odyssey 21 E-SUV, built by French firm Spark Racing Technology and powered by dual Formula E motors. This is the teams’ first test at full power – 400kW (536hp). “I’m happy with their reliability,” says Agag, smiling. “Normally with new technology and so many cars, a lot of things go wrong. But the only thing that has is the fog.”

The morning sun is already burning that fog away, revealing cars being flung around by some of the most skilled drivers on the planet as drones hum around them like mosquitoes. These will capture the action during the spectator-less races, streaming it live around the world. Away in the distance stands a lone figure. “Oh look, a nine-time world champion peeing,” deadpans Agag. Sébastien Loeb has done and won it all. After dominating the World Rally Championship for a decade, winning the Race of Champions three times, and finishing second in the 24 Hours of Le Mans, the Frenchman retired in 2012, but then went on to smash the Pikes Peak record at his first try, and come runner-up in the Dakar Rally. But driving for Lewis Hamilton’s X44 team will take him to places, such as Patagonia, where

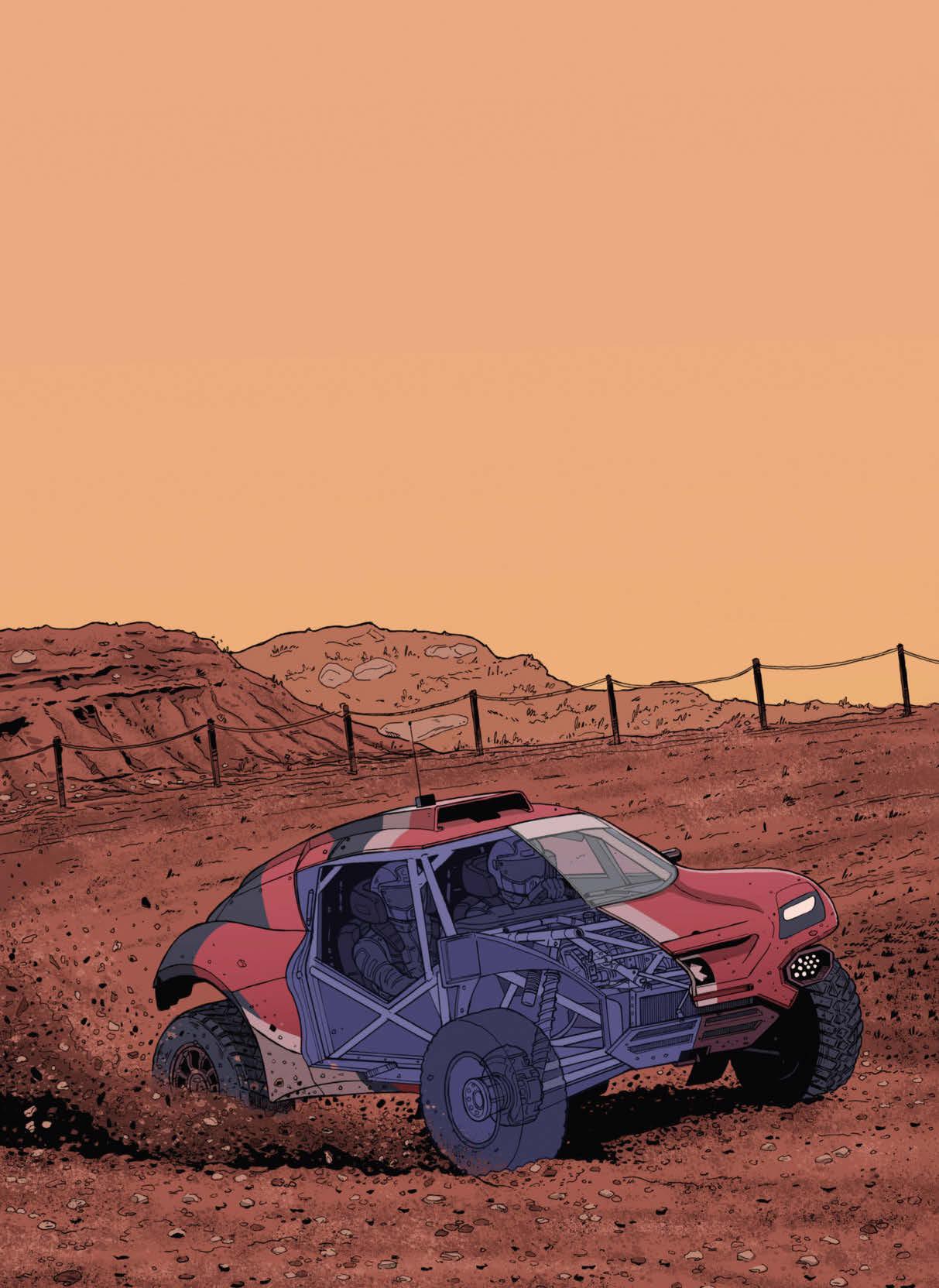

Chip Ganassi Racing’s car goes through its paces. It’s since had a redesign to resemble the team’s GMC Hummer supertruck

3

RACE LOCATIONS Remote areas damaged by human activity 1 ALULA, Saudi Arabia April 3-4 Terrain: desert

Supporting the Great Green Wall initiative to reverse desertification

2 LAC ROSE, Dakar, Senegal May 29-30 Terrain: beach

Assisting Marine Protected Areas and repairing coastal damage 4 2 1

5

3 KANGERLUSSAQ, Greenland August 28-29 Terrain: arctic

Helping countrywide clean-energy solutions to slow global warming 4 SANTAREM, Para, Brazil October 23-24 Terrain: Amazon

Replanting an expanse of rainforest the size of the race area each year 5 TIERRA DEL FUEGO, Argentina December 11-12 Terrain: glacier

Highlighting the rapid recession of the ice sheet in Patagonia

1. Capable of running on one engine 2. Fuel: low-sulphur marine diesel 3. A-deck: science and research laboratory 4. B-deck: car hangar and presentation area 5. Cars loaded/offloaded via crane 6. Hydrogen fuel-cell generators on board to charge cars Length 105m Tonnage 6,767 Cabins 62 Capacity 110 persons EXTREME E’S FLOATING COMMAND CENTRE Transports all the cars to ports nearest each of its five race locations, across four continents. This reduces the race series‘ CO2 emissions by two-thirds compared with air freighting Maiden voyage 1990 Build cost £32 million Home port Liverpool, UK Former service Royal Mail ship

Extreme E’s CEO Alejandro Agag (left) takes a break at the Aragón test circuit to chat with race legend Sébastien Loeb

he’s never raced before. “It’s something completely new and I wanted to discover that from inside,” says rallying’s serial achiever. “If we want motorsports to continue in the long term, it’s good to take new directions. This is one.”

At 1,650kg, the Odyssey feels heavier than the highly developed, astonishingly quick WRC cars Loeb is used to. “It’s quite technical to drive,” he says. Usually reserved, rarely smiling, he’s nonetheless clearly thrilled. “We have to fight with the car sometimes. But that makes it exciting. I think in the desert it will be really fun.”

From those who’ve left an indelible mark to those just beginning to make theirs, Extreme E’s drivers are diverse by design. Its youngest is 22-year-old Brit Jamie Chadwick; its oldest, Spaniard Carlos Sainz, is 58. This is also the first motorsport to feature a 50/50 gender split. Male and female racers compete on equal terms, inspired by mixed-doubles tennis at Wimbledon. “I liked the format because the men and the women are equally decisive for victory,” Agag says. “So I thought we should play this championship as teams – one man and one woman doing two laps, one each.”

One of the championship’s youngest drivers, 23-year-old Catie Munnings, describes Extreme E as “inspirational. It’s going to encourage girls to have a serious career in motorsports at the right age. And for young drivers, it’s the future.”

Munnings got her career off to a flying start, winning the European Rally Championship Ladies Trophy in 2016 in her first season, the first British driver to claim a European title in almost 50 years. But, after a tough first year in Junior WRC in 2020, she’s joined the Andretti United Extreme E team with World Rallycross champion and fellow Red Bull driver Timmy Hansen. “Women aren’t in the teams just for the media,” she says. “Everyone’s been picked on merit. All that money, that development, the hours – it’s pointless unless you’ve chosen someone because you think they’re fast.”

Temperamentally, Munnings couldn’t be more different from the low-key Loeb. While the taciturn rally deity is unlikely to get his own talk show any time soon, the chatty Munnings has already hosted her own children’s TV series: Catie’s Amazing Machines. While she’s clearly thrilled to be in such company, and confesses to having done double-takes while hanging out with some of her sport’s greatest names, the Brit isn’t fazed by the calibre of competition: “We’re all just drivers learning a new car.” But then, this is a woman who won her first international rally after surviving a massive crash, and took her Biology A-level the day before qualifying.

Today’s test is a data-logging exercise, but one pair seem to be having more fun than is necessary: the American team owned by NASCAR’s Chip Ganassi. Drivers Sara Price (a former dirt-bike champion) and off-road racer Kyle LeDuc are going all-out with big jumps and gravel-pinging tail slides. A camera crew are showered with grit as the car careens around a bend. They’re finally ordered out of the way by an anxious marshal, who warns that the Ganassi car span out of control earlier after “popping a tyre off”.

It takes up to two hours to charge Odyssey 21’s batteries for 20 minutes of testing. Range remains a perennial problem for electric cars, so races are short at just two 16km laps. On X Prix weekends, each team is allowed one full charge for the day’s two races. After a few spirited test laps, a plasticky electrical whiff emanates from the Ganassi car. They all seem to do it, but it’s not a smell anyone would want coming from their fusebox at home.

Above: Odyssey 21’s plant-fibre shell is lifted to reveal its tubular frame. Right: Catie Munnings wraps up a test run. Below: Adrian Newey

Most electric cars today are powered by lithium-ion batteries, which, on rare occasions, have caught fire, even exploded, in a reaction known as ‘thermal runaway’. But safety is a priority in any motorsport, and Extreme E has a team trained to extract drivers from electric vehicles. Agag insists the Odyssey 21’s batteries, made by the British company Williams Advanced Engineering, are extremely safe, explaining that Spark’s own test driver rolled his car earlier and experienced “no problem at all”.

Lithium ion presents another concern. Mining for ‘white gold’, as lithium is known, has a devastating impact on ecosystems around the world. Agag is fully aware of the issue, but takes a pragmatic view that climate change is the more pressing threat. “The most urgent thing is not pollution caused by minerals, it’s CO2 in the atmosphere,” he says. “We have to make a choice, and that is to try to cut the CO2 in the atmosphere and the toxic particles coming from cars. For that, batteries are the solution. Are they perfect? No. Are they better than a diesel car in the city? Definitely.”

Adrian Newey has been converted to the cause, which is praise indeed. His cars have won more than 150 Grands Prix, and secured four consecutive F1 drivers’ and constructors’ championships for Red Bull Racing between 2010 to 2013. The 62-year-old engineer and designer has stood at the pinnacle of racing since the 1980s, when F1 teams ran, in his words, “on a diet of cigarettes, coffee and beige polyester”. Fossil fuels have been the lifeblood of his exceptional career. Now, as ‘lead visionary’ of the Veloce Racing team, Newey has been presented with a new challenge. “[Extreme E] is an interesting concept to combine technology with conservation,” he says. “We know we’re damaging the planet. Everybody is grappling with how we reverse that process.”

For Newey, climate change is a complex engineering problem, but he’s sceptical about battery technology as a long-term solution: “It’s not quite the panacea that governments make it out to be.” He believes the automotive industry has been “press-ganged” into embracing it. “But it will grow and mature, just as the combustion engine did,” adds Newey. “And other sources will creep in –hydrogen being the most obvious.” He’s a big advocate of hydrogen, and would like to see it fuelling Extreme E as soon as season three: “Hopefully, by then, the boat will be converted to hydrogen and become very sustainable.”

Newey was introduced to Extreme E by his racing-driver son Harrison, who helps run Formula E champion Jean-Éric Vergne’s Veloce team and its esports sister company. “A huge number of people watch gamers competing, and audience figures are massive,” says Newey Sr. “Hopefully, Extreme E will appeal to the same demographic.”

Agag, a gamer himself, definitely had Gen Z’s digital natives in mind when brainstorming both Formula E and his new venture; he even lifted a few tricks from video games. Take ‘Hyperdrive’, where the Extreme E team who perform the longest jump on the first jump of each race get a speed boost to deploy at will. “That’s from Mario Kart,” he admits.

“Alejandro has shown tremendous vision,” says Newey. “I wouldn’t be involved if I didn’t think it had something to offer. We’re not in it for commercial gain – we believe in it.”

But how did a career politician metamorphose into a planet-saving motorsports visionary? Intelligent, charismatic and ambitious, by the age of 25 Agag was a rising star in Spain’s centre-right People’s Party and had been appointed as political aide to Prime Minister José María Aznar. He was elected an MEP three years later and married the PM’s daughter Ana Aznar – after reportedly proposing in her father’s offices – in 2002. The nuptials

were attended by Spain’s king and queen as well as its celebrated crooner Julio Iglesias, Rupert Murdoch, and members of the world’s political elite. Tony Blair and Silvio Berlusconi were witnesses. Though strongly tipped as a future party mover-and-shaker, Agag had, by then, already quit politics. He never returned.

Decamping to London, armed with his book of stellar contacts, he moved into motorsports, thriving in the notorious shark pool of F1 and forging a reputation as a formidable dealmaker. In 2002, alongside Flavio Briatore (then managing director of Renault), Agag snapped up Spanish TV rights for F1; in 2007, as part of a consortium with Briatore, F1 chief executive Bernie Ecclestone and steel magnate Lakshmi Mittal, he acquired EFL Championship football team Queens Park Rangers; and the following year he bought an FGP2 racing team. “Being a politician never leaves you completely. It helps you create agreements and places where people can meet,” says the man with the golden SIM card. The next chapter was Formula E, which he started with FIA president Jean Todt in 2014, partly in response to motorsports’ growing image problem. In the 2019 Formula E documentary And We Go Green, Agag is seen reclining on a sofa, puffing on a fat cigar as he recalls, “I tried to convince a company to become a sponsor for Formula One. And in every email they said, ‘We cannot be involved, because it’s polluting.’ I thought, ‘We have a problem.’”

As Greta Thunberg’s generation approaches the age that Agag was when he entered politics, the environment continues to climb the world’s political agenda. For Agag, the climate fight should now be “above politics”. From Extinction Rebellion to ExxonMobil, everyone has a role to play. Sport, he believes, can be an agent of change. “Out of the 25 most-watched TV programmes in history, 24 have been sporting events,” he says. “It has the possibility to spread the message in a much wider way.”

Imaginative, driven, seriously wealthy – he dug into his own, evidently very deep, pockets to fund Extreme E – and not so much well-connected as plugged directly into the international power grid, Agag is clearly a man who can sense which way the wind is blowing. And, right now, it’s blowing very much in his favour. R ipping across the sand in an elderly open-top Land Rover, Extreme E’s sporting manager Guy Nicholls shouts directions over a roaring sea wind: “Right at the porpoise.” To the left is the Atlantic Ocean; on the beach to the right, a badly decomposed dolphin carcass. The sorry cetacean’s final resting place is an ugly tide mark of plastic detritus stretching into the hazy distance. “It’s tough to see this,” says Nicholls as the driver steers inland.

Senegal’s coastline – more than 700km long, including estuaries – is drowning in plastic waste. The whole of Africa is choking on the stuff. It clogs roads, pollutes soil and contaminates animal feed. Rain washes it into waterways and, eventually, the sea, where it’s ingested by marine life or spat back onshore by the tide. According to an industry report in 2019, almost 360 million tons of plastic were produced the previous year – more than the combined weight of every human on Earth at the last estimate. Plastic can take up to 1,000 years to biodegrade, and it doesn’t only harm dolphins; it breaks down into tiny shreds that can affect human development, reproduction and health. A 2019 study by the University of Newcastle, Australia, found that the average adult consumes the equivalent of a credit card every week, and

At Lac Rose, Senegal, a volunteer collects plastic waste to make an ‘ecobrique’, which can then be used in building construction

Overall length 4.401m Overall width 2.3m Overall height 1.846m Front/rear track 1.99m Ride height 0.45m Wheelbase 3.001m Weight 1,650kg

1. Niobium-reinforced steel alloy tubular chassis and roll cage 2. Bcomp plant-based fibre body shell 3. Electric power-steering system 4. Lithium-ion battery with 20 minutes of charge 5. Extreme-terrain tyres by Continental Top speed 200kph/124mph 0-100kph/ 0-60mph 4.5 seconds Suspension travel 385mm Maximum power 400kW/536hp E-motor torque 920Nm POWER SOURCE Portable fuel-cell generator shipped to the races creates zero-emission hydrogen fuel on site, by water electrolysis or solar charging

GENDER EQUALITY Two drivers per team: one male, one female – alternating as driver and co-driver for one lap each

2 1

3 4

5

Above: the Andretti United Extreme E race car. Opposite page: Senegalese fisherman Abdou Karim Sall surveys the mangrove swamps in his pirogue

microplastic particles have been found in the placentas of unborn babies.

Nicholls and his team are at Senegal’s Lac Rose beach for their first recce. In May, they will be followed by the whole travelling circus. The Ocean X-Prix will transform this sprawling sand pit into a buzzing techno-village. Container lorries will shuttle race cars, service vehicles and equipment from RMS St Helena, docked at the capital, Dakar, an hour’s drive away. And 70 air shelters – those giant inflatable tents used by relief organisations and murder investigation teams – will house the race command centre, driver change area and garages.

As sporting manager, Nicholls’ first job is to sketch a circuit onto this “huge canvas” that’s practical, televisually appealing, exciting and safe. Mapped out by pairs of flags – “rather like downhill skiing” – each five-minute lap will send drivers out along the beach, returning on bumpier, jumpier inland terrain. “It allows them to go one route or another,” explains Nicolls, who will return in a few weeks with racing driver Timo Scheider and a fast dune buggy to fine-tune the course. “It’s up to them – the shortest distance between two points is not always the quickest.”

Behind the dunes lies Lac Rose, or the Pink Lake. Today, its salty water is rusty grey, but pigmented algae sometimes turns the lagoon a shocking candyfloss hue. For many years, it marked the finish line of another famous – or, more accurately, infamous – off-road race. If Extreme E promises a greener future for motorsports, the bad old days of the Paris-Dakar Rally embodied their grubby excesses. The spectacle of wealthy westerners speeding through impoverished African countries, leaving dust, destruction and deaths in their wake, did little for the sport’s environmental reputation. But it brought visitors and international attention. Since the Paris-Dakar left Africa in 2009, the local community has felt its loss.

“It was one of the biggest events showcasing Senegal, but when it left people didn’t reinvent the destination,” says Senegalese eco-entrepreneur Stephan Senghor. Pink Lake is no longer a tourist hotspot, and the neighbouring village of Niaga faces “a cocktail of challenges – people are living with the bare minimum here”.

Niaga’s dusty main street is alive with activity and colour, its shops and stalls trading everything from truck parts to traditional dresses, but plastic trash is everywhere; scruffy goats and bony cows graze on it as they wander the roadside. Africa leads the world in its ban on plastic – last year, Senegal prohibited all water sachets and plastic cups – so why is it still so ubiquitous? One reason is that the continent remains among the developed world’s favourite dumping grounds. Shipping plastic waste to Africa is cheaper than recycling it. Out of sight, out of mind.

Senghor has devoted much of his adult life to cleaning up his homeland. After studying and working in Canada, he came back with an idea to turn plastic waste into building materials. His fix is simple, ingenious and low-tech: filling soft-drinks bottles with compacted plastic waste. Cemented into walls, these ‘ecobriques’ make strong, long-lasting structures.

Now, with Extreme E’s support, Senghor’s organisation is helping Niaga reinvent itself as a sustainable community or ‘EcoZone’ – a living lab showcasing environmental initiatives while improving lives. Working with schools, Stephan incentivises children by gamifying litter picking. Every ecobrique made can be redeemed for money for community schemes. If successful at the Pink Lake, the project will expand, perhaps into other African countries. “This is the first time they have a race where a project comes with it,” he says. “It’s about how can we be side by side, doing stuff together. Everything is possible if we want it to be.”

Abdou Karim Sall was “born a fisherman” in Senegal’s Saloum Delta, a four-hour drive from Dakar. A physically imposing man with a piratey past, the 55-year-old once kidnapped a Chinese sea captain. For decades, foreign commercial fishing vessels have looted West African waters. Each one can sweep 250 tonnes of fish into its nets daily – 50 times what a local boat catches in a year. So Sall boarded one of these mega-trawlers and abducted the captain. He was jailed the next day, but a mob of angry fishermen persuaded police to let him go. The episode made national headlines, forcing the government to negotiate a solution.

“To solve problems, you have to create other problems,” Sall says, matter-offactly. That was 30 years ago. Today, he insists, his swashbuckling days are over: “Sometimes it’s necessary to do bad things. But I was younger, I wouldn’t do it again.” However, he’s still banned from China. “They will never give me a visa,” he laughs, looking distinctly unconcerned.

Sall grew up in Joal, a fishing port responsible for more than a quarter of Senegal’s entire annual catch. From the town’s plastic-strewn beach, he launches a long wooden boat called a pirogue. According to one origin story, this traditional Senegalese fishing vessel gave the country its name (sunu gaal means ‘our pirogue’ in the West African language Wolof). Its shallow draft is perfect for navigating the estuarine backwaters where the mangroves grow. It’s hard to overstate the importance of the mangrove ecosystem to both fishing and the environment. The mangrove is the only tree that can grow in salt water. Its tangled roots are a habitat for crabs and shellfish, and a vital nursery for young fish. Mangrove forests create a buffer zone, protecting the land from the sea while sucking up 10 times as much carbon dioxide as the rainforests. “The mangrove is good for the community and for the Earth,” says Octavio Fleury, scientific director of Oceanium, the nonprofit reforesting Senegal’s swamps with help from Extreme E.

When a decade-long drought raised salt levels in the 1970s, large swathes of West Africa’s mangroves died. Senegal alone lost more than 100 million, replaced by lifeless salt flats, empty apart from the tyre tracks of smugglers driving across the delta at low tide from neighbouring Gambia. “It was terrible,” says the Frenchman. “A little change like salinity and all the mangroves can disappear.”

Oceanium pays schoolchildren to collect ‘propagules’ – the mangrove tree’s spear-like buds – and plant them in neat rows across the delta mud at low tide. “The idea is to make restoration easy,” says Fleury, “but we need the population to be involved, to understand the importance of a healthy environment.” Led by Senegal’s environment minister Haidar el Ali, Oceanium enlisted 150,000 people from 500 villages, planting 70,000 hectares across Senegal. Last year, for the Extreme E project, they planted another 63 hectares – roughly 120,000 trees.

While growing up, Sall saw the mangrove forests disappear, but he knew little about their importance. When asked if he’d help plant a million, he replied, “What’s the point?” A decade on, his commitment to the cause is total. Thanks to Sall, more than 500,000 new mangrove trees are growing in the Saloum Delta. The kids call him ‘Mister Propagule’.

But Mister Propagule was not always Mister Popular. When Sall established the waters around Joal as a governmentbacked Marine Protected Area in 2004, local fishermen hated him. “I was everyone’s enemy,” he says. But now, as president of the Fishermen’s Association of Joal and the Committee of Marine Reserves in West Africa, he’s a formidable champion of both the fishing industry and the environment. “To manage local communities here, you need two sides to your character,” he says. “One that is a fighter, and the other with the knowledge to help them understand.”

Sall benefits from Oceanium’s finances and resources, but his local influence is invaluable. “And his mystical support,” says Fleury with a smile, as the bow of Sall’s pirogue noses through overhanging branches. Senegal is predominantly a Muslim country, but the supernatural poetry of voodoo and gris-gris, spirits and sacrifices remains very much alive. Deep in the mangroves are sacred sites. Sall believes the forest genies who live there have always protected his home. Now is his time to return the favour.

If Extreme E is an attempt to ‘greenwash’ motorsports, it is an extraordinarily elaborate and expensive one. And does it really matter? As its founder will tell you, politics is the art of the possible. It’s quite possible that Extreme E will make a real difference in the fight against climate change. After all, how many sports can claim to get motorsports magnates, climate scientists and mystical eco-pirates all working together to save the planet?

SHOOTING STARS

Mysterious illuminations in the town of Marfa, Texas, attract curious visitors from around the world. But one photographer used the location to capture a different kind of fying object – the Red Bull Air Force

Words NORA O’DONNELL Photography DUSTIN SNIPES

The light fantastic

This image is actually 48 photos stitched together. Six cameras each took eight long-exposure shots of the Red Bull Air Force as they jumped from the airplane, went into formation, and finally disappeared behind the mountains. “The result is an abstract light painting with an endless night sky,” says photographer Dustin Snipes.

Snipes (pictured left, with his team) first travelled to Marfa last September to scout potential locations for his shoot with the Red Bull Air Force. “It took months of planning,” he says. “There were a lot of moving parts.”

Like many a wild adventure, it all started with a crazy idea – in this case, executed by American photographer Dustin Snipes. “The crazier the idea, the better,” Snipes says. “Because that means it probably hasn’t been done before.”

In the high desert of west Texas, USA, the veil of the Milky Way drapes across a night sky bursting with stars. Near the small town of Marfa, high elevation and a lack of light pollution provide the perfect spot to view such astronomical wonders – and to examine the mysteries of the area. For more than a century, locals have reported strange, pulsing orbs of various hues, commonly known as the Marfa Lights. Whether they’re UFOs or simply atmospheric reflections of headlights or small fires, the fun lies in the speculation.

Which is why Snipes leapt at the opportunity to capture the Red Bull Air Force against this celestial landscape. What if these world-class skydivers embodied this phenomenon and became the Marfa Lights?

The LA-based photographer spent months planning out the concept, weighing up hundreds of variables with a team of experts. “More than any shoot I’ve done, there were so many unknowns,” he says. After scrutinising iconic local

Opposite: To make themselves visible in a Moonless sky, the Red Bull Air Force wrapped themselves in LED lights; they also added pyrotechnics to help show the speed and energy of the team during free fall. This effect makes the skydivers appear like human comets.