72 minute read

JIM DEEDS

WITH EYES WIDE OPEN

JIM DEEDS

Advertisement

GIFT OF CONFUSION

THERE IS SOMETHING ATTRACTIVE ABOUT CERTAINTY, YET IT IS CURIOSITY THAT KEEPS US SEARCHING AND GROWING.

When I was a young man, I worked in the pub at the top of my street. Each evening I stood behind the bar, served pints of beer and glasses of wine, and listened to the conversations people would have. One evening, I was earwigging (a great old Belfast term for eavesdropping) on the conversation between a young man and an old man about how chaotic the world was. The old man, in an effort to find some certainty, told the young man, “Wherever you go there's two things you can be certain to find – a bottle of coke and an Irish person!"

There's something attractive about certainty. Most people seek it out in some way or other. We like to know things. We like to be sure of things. I guess it gives us a sense of security in a world that often feels anything but secure. One thing about certainty, though, is that it can feel like the end of a road.

In this way, certainty, or our perception of having it, represents the end of something and closes us down. I say 'our perception' of having certainty, because often times what we hold as certain, really isn't. This happens, for example, when people are labelled as being one way or another. So, one 'certainty' could be that all people of a certain religious persuasion are evil. Another could be that all people who vote in a certain way are crooked or racist or immoral. When we step back and think

rationally, we see that this is just not the case. Life is much more complex than that. So, the things we often hold as certainties, may well not be certain.

Certainty can become a terrible addiction, though. It can become like a drug that anaesthetises us against the need to acknowledge the fact that there is so little of it about! One polar opposite of certainty is confusion. Mostly, we don't like confusion. It muddies the water. It's uncomfortable; distressing even.

And yet confusion keeps us searching. Confusion keeps us open to being curious. And curiosity is the key to growth. Rather than spelling away whole groups of people or opinions we don't agree with or understand, embracing our confusion can allow us to be curious about what is going on. We can be drawn to find out more. Allowing ourselves to feel confused acknowledges that 'I' am not the font of all knowledge. It says that 'I' need growth and more work and more insight in order to understand 'us'. In this way, confusion is the gift of growth. It's nothing to be afraid of. It is to be welcomed as a friend. It is to be our guide to find ways to reach out to other people to find out more.

All this is not to say that there are no certainties at all. It is not to say that there is no truth. It is not to say that there is no right or wrong. It is simply to say that we could be aware of those things that present as certainties and remain curious about them.

I'm always drawn to the first words in the Bible where we read of our creation story. In Genesis chapter 1 we read that before God brought light (certainty) to the world there was a formless void (confusion). It was the love of God's spirit hovering over the chaos that brought the light.

Confusion + God = Certainty. I like that!

It does not deny our confusion. It does not seek to correct it. It seeks to welcome God into our confusion and to bring light to it. As we travel through this month of November, we remember our dead. Dying and the loss of a loved one can call our certainties into question – indeed we can question the whole meaning of our existence. We can be confused about God and what God is at allowing our loved one to be taken from us. This month is a perfect time to remember the equation above:

Confusion + God = Certainty

When we welcome God into our confusion, sorrow and grief, we will find that God wants to console us and wants us to hold on to the certainty of God’s 19 love for us, living or dead. God wants us to know, for certain, that death is not the end; rather a door we must go through in order to dwell evermore in God’s loving embrace.

If I could go back in time to that bar where I worked when I was a young person, I'd give that old man a different version of his sentence: "Wherever you go there's three things you can be certain to find - a bottle of coke, an Irish person and the Holy Spirit hovering over our chaos."

Belfast man Jim Deeds is a poet, author, pastoral worker and retreat-giver working across Ireland.

CelebratingAdvent

THE SHOPS ARE BEGINNING TO SHOW THEIR CHRISTMAS STOCK. FOR US, IT IS NOT QUITE CHRISTMAS YET. WE STILL NEED TO CELEBRATE THE SPECIAL TIME OF ADVENT.

BY MARIA HALL

20 If Advent means the time of preparation before Christmas, it should probably start in late August! By December, shops are clearing Christmas away ready for Easter. Utter madness! It’s difficult to celebrate the season properly, when we are surrounded by Christmas commercialism for months beforehand, but a rich Advent will lead to an equally rich Christmas, so we should resist the temptation to sing carols too early and instead immerse ourselves in the rich glories of the season.

A LATECOMER?

Advent wasn’t celebrated by the early Christians. Lent and Easter were established feasts long before Advent and Christmas. Instead, their focus was on Christ’s second coming which they expected soon! Advent preparation emerged in the fifth century when there were 40 days of fasting and penance in preparation for baptism on the feast of the Epiphany. From the sixth century, it was known as St Martin’s Lent because fasting began on November 11, the feast of St Martin. Advent as we know it, as a period of remembering and expectation, has existed only since the Middle Ages.

The Greek equivalent of the Latin adventus is parousia, meaning second coming. We associate the meaning of Advent with Jesus’ coming and preparation. We tend to focus on the coming of Christ as a child, laid in a manger. But it is equally about welcoming Christ into our hearts, filling us with grace and joy, and the hope we have for him returning in glory at the end of time.

There is such a wealth of rich resources and creative possibilities that Advent always feels too short! But here are some of the most beautiful prayers and themes which we can focus on, either individually, in parish or in school.

LOVE, JOY, HOPE, PEACE

The Advent wreath has emerged from winter pagan customs involving evergreens, garlands and the hope for more daylight. The modern wreath came from Germany in 1839 where a local minister adorned a cartwheel with four candles for the Sundays of Advent, and 24 candles for the weekdays.

York Minster has a magnificent 3-metrewide wreath, suspended beneath the central tower. Its Advent Service of Light is always a packed occasion, where 2,000 people experience the power of light and listen to the themes of Advent; hope, peace, joy and love.

Watching the candles lit each week is a great countdown itself, but these themes have potential for reflection and personal prayer. Let’s not just count the candles; take a theme a week and focus on how it can be effective in our own lives and the world around us.

MAGNIFICAT, BENEDICTUS, NUNC DIMITTIS

These three beautiful canticles (songs) are prayed during the Liturgy of the Hours and are perfect for focusing on during Advent. They are all exclusively part of the infancy narrative of Luke and deserve to be used beyond the Prayer of the Church. As songs, they are very accessible and there are many wonderful settings which you could listen to as part of an Advent preparation and include in Advent liturgies. I have recommended a few, but you could have fun searching on YouTube for your favourite!

THE MAGNIFICAT

This is probably the oldest Marian hymn and

is sung during Vespers. It’s easy to have a

romantic image of Mary, visited by the angel

Gabriel, declaring her love for and obedience

to God. But there’s so much more to reflect

The first half is beautiful and timeless in its declaration of humility and praise of God.

The second half of the Magnificat is radical so that public recitation has been banned in several countries! Dietrich Bonhoeffer called it “the most passionate, most vehement, one might even say the most revolutionary Advent hymn ever sung." Oscar Romero said:

The person who feels the emptiness of hunger for God is the opposite of the self-sufficient person. In this sense, rich means the proud, rich means even the poor who have no property but who think they need nothing, not even

God.

This is the wealth that is abominable in God’s eyes, what the humble but forceful Virgin speaks of.

This prayer offers us much to consider; joy and exaltation, humility and holiness, the transformation of the weak and helpless and triumph over injustice and oppression We should listen, sing, pray and act! * Listen to: Magnificat in C Minor, Dyson.

Magnificat in C, Walmisley. Settings by JS

Bach and Bernadette Farrell.

THE BENEDICTUS This canticle, also known as the Song of Zechariah, is sung

and so relevant in the 21st century - so much at Morning Prayer and has been prayed since the sixth century. Like the Magnificat, it is a prayer of two halves. Firstly, Zechariah gives thanks for what God has done thus far, his promise through the prophets of

being saved, and of the Saviour’s birth. In the second half, Zechariah is speaking to his son, John the Baptist. It is father singing to his son in the most cherished and intimate way: "You my child will go before the Lord to prepare his way."

The final lines are a beautiful prayer in themselves:

In the tender compassion of our God the dawn from on high shall break upon us, to shine on those who dwell in darkness and the shadow of death, and to guide our feet into the way of peace. *Listen to song settings by Michael Joncas and Bernadette Farrell.

THE NUNC DIMITTIS

This short canticle has been part of the liturgy since the fourth century and is sung at Night Prayer (Compline). We also hear it each year on the feast of the Presentation. It has inspired some evocative musical settings. Simeon waited in hope to see the Messiah and was rewarded. His prayer of joy and thanks can inspire us and give us hope as we await the Christ’s return. *Listen to stunning choral settings by Geoffrey 21 Burgon and Herbert Howells.

O ANTIPHONS

O Sapientia (O Wisdom)

O Adonai (O Lord)

O Radix Jesse (O Root of Jesse)

O Clavis David (O Key of David)

O Oriens (O Dayspring)

O Rex Gentium (O King of the Nations)

O Emmanuel (O God with us)

The O Antiphons are a hidden gem of Advent. If you pray Vespers daily, you will know that they are the antiphons of the Magnificat from December 17-23. They are also the weekday Gospel Acclamations for that time. While we can pray them as part of Evening Prayer, they are perfect for a short daily reflection at home or in the classroom.

The Antiphons date back to liturgies in Rome in the eighth century though there are references to them in the sixth century. Each antiphon is a title of Christ drawn from the Old Testament, together with a prayer of petition. They can be sung, recited, prayed alone or in a group and there are some good reflections with music available on YouTube.

An added feature which hooks in young people

is the hidden acrostic; if you reverse the order and use the initial letters, Emmanuel, Rex, Oriens, Clavis, Radix, Adonai, Sapientia, you will find Ero Cras which in Latin means 'Tomorrow I will come'. The antiphons provide possibilities for homegrown artwork in church and school and there are those produced by the Benedictine sisters of Turvey Abbey which are a beautiful Advent decoration. Delay singing O Come O Come Emmanuel till the second half of Advent and there will be a beautiful symmetry between it and the recitation of the Liturgy of the Hours.

PASTORAL IDEAS

•In schools, it’s impossible to ignore Christmas in December! But focusing on Advent for a couple of weeks will give that period of preparation. Have individual Advent class liturgies, a weekly whole school service with the Advent wreath, and the Sacrament of Reconciliation. •Explore the wealth of Advent carols and hymns. Especially good are Bernadette Farrell’s Litany of the Word and ‘Stay Awake’ by Christopher Walker. •While we should be having carol services in parish in Christmastide, in practice this rarely happens. It is therefore recommended to keep any carol service which focuses on the Nativity, till after December 17. Consider having a carols followed by a period of Exposition and Benediction. This year may pose particular problems as we will have to abide by local pandemic regulations. •There are creative ways of emphasising the waiting and the joyful hope, including the Advent wreath and a Jesse tree. •Evergreens. We shouldn’t be decorating for Christmas too early. Advent is short enough! But as a symbol of God's everlasting love, gradually decorating the church with greenery is a reminder of this and is an anticipation of celebrations to come. •A Christingle service is a great way of involving children. It can be a separate service or form part of the children’s liturgy activities at Mass. •Make a resolution to have a Christian Advent calendar. Advent is not just four weeks in which to prepare for Christmas. Advent is the church’s life. Advent is Christ’s presence... and will bring about God’s true reign, telling us, humanity, that Isaiah’s prophecy is now fulfilled: Emmanuel – God with us.

Oscar Romero

INTERNET RESOURCES

www.mariahall.org/resources www.whychristmas.com https://dynamiccatholic.com/best-adventever/ https://mycatholic.life/advent/

Maria Hall is music director at St Wilfrid's Church, Preston, England. A qualified teacher, she has a Master’s from the Liturgy Centre, Maynooth and is a consultant on matters liturgical for schools and parishes. www.mariahall.org

THE CUP OF DISCIPLESHIP

IN THE MONTHS SINCE CORONAVIRUS STRUCK, ACCESS TO THE CUP OF THE LORD AT THE EUCHARIST HAS BECOME LIMITED TO THE CELEBRANT ALONE. BUT IT REMINDS US OF THE DEEPER MEANING OF DRINKING FROM THE SAME CUP.

BY THOMAS O’LOUGHLIN

Whilst o u r common memory of the origin of the Eucharist is that Jesus took “bread and wine” (emphasising distinct materials), by contrast all our early texts notice that he shared “a cup” (the emphasis on how that drinking took place (1 Cor 10:16 and 21; 11:25, 26, 27 and 28; Mk 14:23; Mt 26:27; Lk 22:17 and 20; and Didache 9:2). Is this of any real significance?

The most obvious evidence that ‘a cup’ was significant in the churches’ memory was that having taken the cup, and blessed the Father, Jesus gave it to those at table so that they each drank “from it”. It was not that they all drank wine – or any other liquid – which they could do from their individual cups, nor that they all had a drink of the same wine in that it came from one source, such as a flagon, but that they passed a cup from one to another and each drank from that same cup.

JUST ONE CUP?

As a start, note just how unusual was this action of sharing a cup. There was no equivalent to it in any known Jewish practice. Making the sharing of a cup part of one’s table manners is confined exclusively to the followers of Jesus. Here we have a practice unique to the churches - indeed, so distinctive that its features of being ‘disruptive of expectations’ and ‘multiple attestation’ (Paul, the Synoptics, the Didache – and, as we shall see, possible John) allows us to see an action that goes back to Jesus himself.

While drinking is a part of the meal rituals of all cultures, regularly passing a cup is rare. While we love to share meals, we want our own drinking vessels. Only in emergencies (one canteen of water) or situations of exceptional informality (two friends, one beer, and no cup) will we share one container. This human insight alerts us that, firstly, the widespread adoption of this action of sharing a cup cannot be dismissed as some minor detail. Secondly, we can see why virtually Christian tradition has an unspoken aversion to it.

SIGNIFICANCE

For Paul, the choice facing those who share the cup is between “the cup of the Lord and the cup of demons. You cannot partake of the table of the Lord and the table of demons” (1 Cor 10:21). This choice between the Christ and the demons was a choice that faced all Gentile disciples: were they willing to turn from the idols that were part of the social and domestic fabric of Greco-Roman urban life? If one wanted to express the new discipleship then one not only turned from that which had been offered to idols, but one partook of the common cup of the disciples of the Christ. Drinking from the common cup was a ‘boundary ritual’ that expressed commitment to discipleship, and as such was a serious matter and they would have to answer for their decision to drink from that common cup (11:27-8).

Since it is the action of declaring both commitment to discipleship and rejection of idols, it is a participation in the life-blood of the Christ (10:16) and makes them part of the new covenant which was sealed in Christ’s blood (11:25). For Paul, discipleship is about being part of the new covenant and sharing in the new life offered by the Christ; and taking the common cup – not a gesture done lightly – was accepting that discipleship and taking that lifeblood of the Christ into one’s own body. We are accustomed to think of the act of baptism as the boundary ritual of the new community, but for Paul at the time he first wrote to the Corinthians, the sharing of the cup was also a demarcation ritual – and since it was repeated weekly it was the ongoing declaration of willingness to continue along the Way. That such a paralleling of drinking the cup with baptism was present in Paul’s mind when he wrote about that church’s meals is confirmed by his remark about the Spirit being present in that church: “For by one Spirit we were all baptised into one body – Jews or Greeks, slaves or free – and all were made to drink of one Spirit” (12:13). Just as the Spirit united them in baptism, so the Spirit was now what they drank in common. In short, if they wanted to be part of the new people, then they drank from the common cup, accepting the consequences.

The assumption of the Didache is that those who are eating at the meal have already made a choice between the ‘Way of Life’ and the ‘Way of Death’; and it is explicit that only those who are baptised are to eat and drink (9:5) – so willingness to eat from the loaf and drink the one cup are marks of continuing commitment. This relationship between baptism and drinking as boundaries may seem strange to us who put these ‘sacraments’ into different theological compartments: one is about joining and a one-off event, while the other is about continuing and is repeated over a lifetime. However, such a neat system of ‘outcomes’ does not fit with

how ritual establishes and maintains identity. One-off events need to be constantly recalled, while that which is an ongoing concern needs to be seen to have a moment of establishment. They were living as disciples – dayby-day facing its challenges – and so they declared themselves day-by-day while looking back to the moment when discipleship was established. The two rituals, baptism and drinking the common cup, need to be seen as complementary within living a life of commitment, rather than as distinct from one another with different functions in a theological system.

Looking at the gospels we see that the one cup of the Lord is taken as willingness to accept all that discipleship involves. The scene appears in Mk 10:35-40 where James and John, the sons of Zebedee, ask if they can sit beside Jesus in glory. This prompts a challenge that links drinking the same cup as the Lord with baptism: “Are you able to drink the cup that I drink, or be baptised with the baptism that I am baptised with?” (10:38). When they reply that they are able, they are told that “The cup that I drink you will drink; and with the baptism with which I am baptised, you will be baptised” but that will not guarantee them their desired places. To be a disciple is both to share in the baptism of Jesus and to drink the same cup as him. In Mt 20:20-23 the story re-appears but now the question is asked by their mother and the reference to baptism has disappeared, but the message is just as stark: to be a disciple means drinking from the same cup that Jesus drinks – and this invites from the audience a ritual conversion: if you drink the ritual cup, then you consciously declare your readiness to accept the cost of discipleship.

This linking of the cup and discipleship is further developed in that Jesus’ own discipleship to the Father is presented as his willingness to drink the cup that the Father offers him. In both the Synoptics and John, the suffering the Father’s Anointed must undergo is presented in terms of his “cup” and Jesus’ willingness to drink it. In Mk 14:36, followed closely by Mt 26:39 and Lk 22:42, this is presented as part of his prayer in the garden: “Abba, Father, … remove this cup from me; yet, not what I want, but what you want.” Thus with obedience he accepts where

his discipleship has led. In Jn 18:11, Jesus does the Father’s will without hesitation, but again he is drinking “the cup” that the Father has given him.

Drinking from one cup was an acceptance of a common community destiny. As such, it formed a very real, and possibly physically dangerous, boundary for them. It was also an act that shattered other boundaries such as those of race, social status, and factions with the churches, and implied a willingness for a new fictive community and a new intimacy in Jesus. Sharing a cup they had become blood brothers and sisters.

AND TODAY …

Does this call to drink from the one cup pose a challenge to contemporary Christian practice? It could be argued that sharing the cup is now common in many communities – though Catholics still find it most unusual. Our hesitations to sharing a vessel that touches our lips are deepseated. The Orthodox churches,

Our hesitations to sharing a vessel that touches our lips are deepseated. The Orthodox churches, for example, use a spoon – which destroys the gesture’s force. Some Protestant churches use individual thimble-sized glasses

for example, use a spoon – which destroys the gesture’s force. Some Protestant churches use individual thimble-sized glasses that are as destructive of Jesus’ bold symbolism 25 as pre-cut Catholic wafers destroy the original loaf symbolism, while both transmit signals that appeal to an individualistic consumerist culture.

The fact that most Christians try to avoid sharing the cup is a powerful reminder that discipleship involves hard choices: discipleship costs!

“Examine yourselves, and only then eat of the loaf and drink of the cup” (1 Cor 11:28). Can we face the common cup of shared covenant discipleship?

For further reference see J.P. Meier, ‘The Eucharist at the Last Supper: did it happen?’ Theology Digest 42(1995)335-51.

A native of Dublin, Professor Thomas O’Loughlin taught in the Milltown Institute and the Dominican Studium in Dublin. He is currently Professor of Theology at the University of Nottingham. His most recent book on the Eucharist is Eating Together, Becoming One: Taking up Pope Francis’ Call to Theologians (2019).

THE AMERICAN ELECTION

THE AMERICAN SYSTEM OF ELECTING THE PRESIDENT IS UNLIKE ANY OTHER IN THE DEMOCRATIC WORLD. WHILE IT IS USUALLY PRESUMED THAT THE PRESIDENT IS ELECTED BY THE MAJORITY OF THE VOTES CAST, THAT IGNORES THE MYSTERIES OF THE ELECTORAL COLLEGE.

BY GERARD MOLONEY CSsR

In the US presidential election of 1948, pollsters and pundits all agreed that Republican Governor Thomas E. Dewey of New York would easily beat incumbent Democratic President Harry S. Truman. Dewey had lost narrowly to Franklin Roosevelt in 1944 and was a hugely popular governor of the nation's most populous state. Truman was regarded as an accidental president, in office only because Roosevelt had elevated him from relative obscurity to be his running mate in 1944. The economy was suffering from post-war blues. After almost two decades of uninterrupted Democratic rule, it seemed the electorate was crying out for change.

But the indefatigable Truman would not throw in the towel. He crisscrossed the country by train, tirelessly campaigning right up until election day. As the polls closed, all seemed set for a comfortable Dewey victory. The Chicago Tribune newspaper jumped the gun, with a giant headline on its front page declaring “Dewey defeats Truman”. For all his public optimism, Truman went to bed that night thinking the election was lost.

But the Chicago Tribune, like the majority of pollsters and pundits, had got it wrong. Truman had won. Against all the odds, he had triumphed narrowly. A famous photograph shows a beaming Truman proudly displaying a copy of the Chicago Tribune with its now infamous banner headline.

HARD TO PREDICT

Opinion polls were in their infancy in 1948, so pollsters could be forgiven for getting it wrong. Four years ago, pollsters failed to take the influence of social media into account when predicting an easy Clinton victory over Trump. The Trump campaign had used Facebook and other social media to manipulate potential voters in a sophisticated operation the likes of which had never been seen before. Based on people's psychographics as well as demographics, they were able to target those most likely to support Trump while also encouraging Black voters and other likely Clinton supporters to not vote at all. To the consternation of those Trump might label 'the liberal elite', the Trump campaign's strategy succeeded beyond their own wildest dreams.

As those who confidently predicted a 'yes' vote in the UK's Brexit referendum now know to their chagrin and bitter cost, making election forecasts in

Western democracies is always a risky business. Just ask Theresa May, who was convinced she would win a resounding majority when she called the snap general election in 2017.

US ELECTORAL SYSTEM

In addition to the vicissitudes of the electorate,

and the influence of social media, the peculiarities of the US electoral system make predicting presidential election outcomes all the more dangerous.

The United States has a unique method of electing presidents. It is not done by the people in a first-past-the-post system as in most democracies (or by proportional representation with the single transferrable vote, as in Ireland) but by the 535 members of an electoral college. Established by the United States Constitution, the electoral college is a body of electors which forms every four years for the sole purpose of electing the president and vice president of the United States.

Membership of the electoral college is based on the number of seats each state holds in the United States Congress. Each state elects the number of representatives to the electoral college that is equal to its number of senators—two from each state—plus its number of delegates in the House of Representatives. Each state elects representatives to the 435-member US House of Representatives based on its population. California, the most populous state, has 53 representatives in the United States House of Representatives. Wyoming, a sparsely-populated state, has one US representative. This means that California has a total of 55 electoral college votes (2 plus 53), while Wyoming has three electoral college votes (2 plus 1).

With a couple of exceptions, the winner of the popular vote in each state wins all that state's electoral college votes (Maine and Nebraska use a form of proportional representation). The winner of the popular vote in California, therefore, receives that state's 55 electoral college votes, while the winner in Wyoming receives its three votes. The candidate who wins more than half of the electoral college votes (270) wins the presidential election.

PROTECTION AGAINST POPULISTS

One reason for the electoral college was because the drafters of the constitution were wary of a direct election to the presidency. They feared someone could manipulate public opinion and take power. They worried that, in a vast and diverse continent, most voters would not have sufficient information to choose carefully and intelligently among leading presidential candidates. The electoral college, hopefully, comprised of wise, wellinformed electors from each state, would act as a kind of buffer or safety valve between the population and the election of the president. A second reason for the electoral college was to protect the interests of the slave-owning southern states, who feared that in a direct election, candidates from the more heavilypopulated northern states had an inherent electoral advantage.

ANACHRONISTIC AND UNDEMOCRATIC

There are growing efforts today to abolish the electoral college as being anachronistic and undemocratic. The most glaring disadvantage of the system is that a candidate can win the popular vote, but lose in the electoral college, as happened four years ago when Hillary Clinton won almost three million more votes than Donald Trump. (By eking out wafer-thin winning margins in several swing states, Trump was able to exceed the magic 270 electoral college votes). In fact, five times a candidate has won the popular vote yet lost the election: Andrew Jackson in 1824 (to John Quincy 27 Adams); Samuel Tilden in 1876 (to Rutherford B. Hayes), when the result was decided by the US House of Representatives; Grover Cleveland in 1888 (to Benjamin Harrison); Al Gore in 2000 (to George W. Bush), when the Florida recount lasted 36 days before the US Supreme Court gave the election to Bush; and Hillary Clinton in 2016 (to Donald Trump). So it is possible again this year for Trump to be returned to office with far fewer votes than Joe Biden.

Indeed, since 1988 the Republican candidate has won the popular vote on only one occasion when George W. Bush narrowly defeated John Kerry in 2004.

An additional complication this year is the postal vote. More US citizens than ever are going to vote by absentee ballot. This means that, unlike on most occasions in the past, the winner may not be decided on election night, because it will take more time to count the postal votes. The election drama might not end on November 3 but go on for quite some time afterwards.

Fr Gerard Moloney CSsR was editor of Reality for many years. He has a fascination with American politics that goes back to his school days in Doon, Co Limerick.

FUNERAL IN THE PHILIPPINES THE AUTHOR ONCE FRIGHTENED HIS HOSTS WHERE HE WAS SPENDING THE NIGHT BY ADOPTING THE POSITION OF A CORPSE. IT WAS A MORE COMFORTABLE POSITION FOR HIM TO SLEEP IN, BUT IT CAUSED THEM A SLEEPLESS NIGHT!

BY COLM MEANEY CSsR

Some years ago, I was spending the night in a house in a rather remote part of the country. The woman of the house prepared for my sleeping in the living room: a mat woven from fibres to lie on and, at one end of it, a pillow and blanket. She had so arranged things that my head would be near the door, so I simply reversed the set-up, with my feet near the door (in case anyone would pass that way during the night). Next morning, she told me that she had slept fitfully, upset and worried about my sleeping position: with my feet facing the door I had unwittingly adopted the position of a corpse, waked, and finally removed from the house feet-first! She had tossed and turned in insomniac unease, wondering if I'd ever again see the light of day!

Filipinos have some unusual beliefs and practices regarding death and burial (which may be of interest to readers at this time of year, November).

HOW LONG DOES THE WAKE LAST?

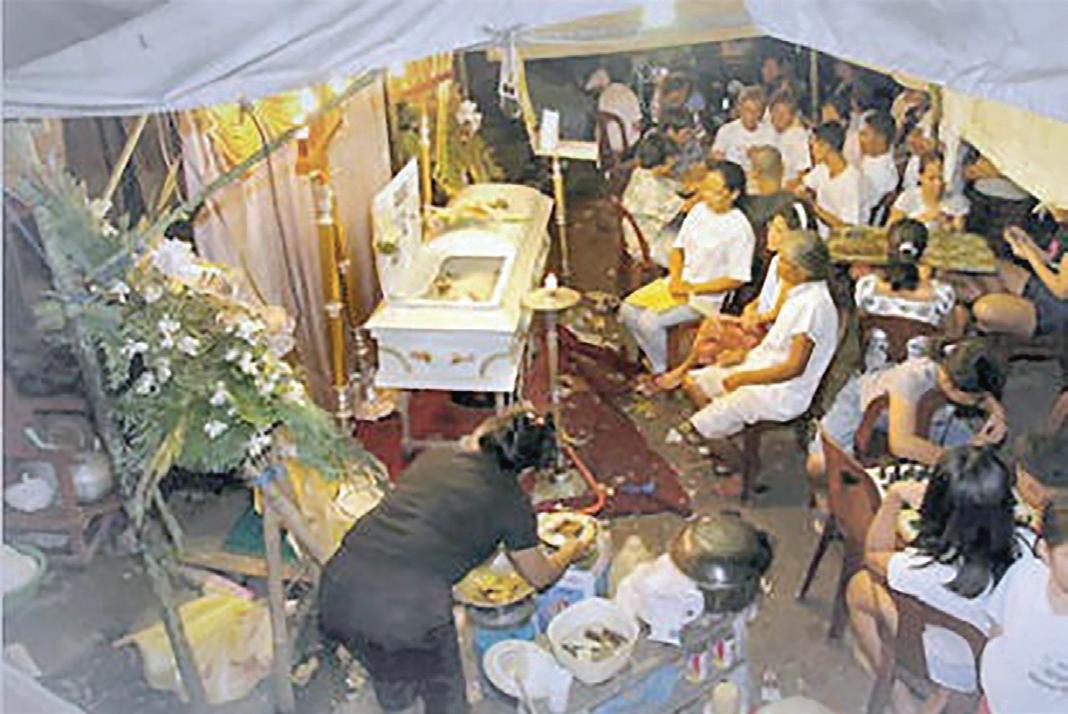

With very few exceptions, almost every corpse in the Philippines is embalmed, vital because of the warm, humid climate: without embalming, the body would quickly putrefy. The wake can last up to two weeks, especially if there are family members travelling from abroad — but even for poorer people, the wake is at least three to four days. In rural areas, the wake is always in the house: in urban areas, it is either at the house or at a funeral parlour. But wherever it occurs, the corpse is never alone; somebody is present all round the clock.

The days and nights pass with different activities: neighbours visit, Mass may be celebrated, other prayers and devotions will be offered by various groups, etc. Everyone who visits is fed: the wealthy employ teams of caterers, the more down-market offer to each visitor a sandwich and some juice. Everyone approaches the coffin and looks at the deceased, who lies, embalmed and with make-up worthy of a Hollywood star, under a pane of glass.

The wake continues day and night, without pause. It's a time to salute the deceased, and to ease, however slightly, the burden of grief on the bereaved. As night approaches, and the other activities have ceased, the vigil begins. For these sleepy hours

Card games at the wake till dawn, a certain resilience and creativity are required. The solution? Playing cards and/or mah-jong (a Chinese game played with small ivory or plastic tiles). And occasionally a drink or two help to pass the long hours till sunrise. (The games and the drinking are too much for some of the puritanical clergy, who mandate that if they continue, there will be no funeral Mass.)

THE FUNERAL

The funeral itself follows the usual format, although be prepared for long and often emotional eulogies. The hearse heads for the cemetery, playing on external speakers some suitable hymn or one of the deceased's favourites (eg Frank Sinatra's My way). The coffin is lowered into the grave in a rural area, or placed into a niche in an 8-foot column, with three or four other niches in each column. After seven years, the bones/dust are then solemnly removed to provide space for the next coffin; this is simply a municipal requirement, due to the large population of the country. In the rural cemeteries, a small fire of twigs is lit and the people step over the fire, through the smoke (this is called palina). Supposedly this is a way of leaving in the cemetery any impurities which may have accrued due to having been among the dead, in other words, a rudimentary form of disinfecting.

Some other unusual customs persist in the rural areas. After the wake, as the coffin is being taken out of the house, all present walk/stoop under it, and they must not look back or return to the house. Walking under the coffin will offset any feelings of undue loneliness for the deceased; not looking back prevents the spectre of the dead from returning.

For the duration of the wake, no sweeping is done in the house, as this could cause other family members being 'swept up' in the dragnet of death. An overarching theme of these restrictions is that, by following them, some illness or misfortune will be duly offset, though it has to be said that the chain of reasoning is often far from clear! For instance, when leaving the cemetery, apart from passing through the smoke of purification, there is also the custom of putting ashes on the mourners and, further, of rubbing the juice of the local lemonsito tree on the mourners' hands — all to ward off any prospective return of the alltoo-recently buried. A somewhat macabre tradition, also supposed to minimise post-mortem loneliness, involves the mourning spouse wearing the underwear of the deceased — although how differences in waist size are negotiated is anyone's guess.

BLACK OR WHITE?

One interesting detail of comparison between our Irish practice and that of the Filipinos is that during mourning we wear black, the quintessential expression of sadness (the darkness of death, etc), whereas in the Philippines at the funeral Mass the mourners wear white (shirt or blouse), with a simple black tag on the breast to express sadness. I wonder if, even amidst their various beliefs and practices surrounding death, they may not have held onto a nugget of vital wisdom: their white clothing expresses the expected joy promised by the Lord. Their white clothes mirror those common-sense defying words of the Preface of the

The corpse is never left alone funeral Mass: "Lord, for your faithful people, life is changed, not ended". What do you mean? The once-alive person is lying cold in the coffin, not a heartbeat, not a breath in the lungs, etc. How can we say, "Life is changed, not ended"?

I think because 'life' is greater than anything our human intelligence or science or wisdom can cope with or measure or define. A table, a tree, a universe — all these describe specific things, finite realities. But 'life', 'existence'? The best we can do to 'measure' life is in terms of heartbeat and other 'vital signs' and once these have gone, we say that the person is literally "life-less".

That, however, sounds like hubris to me, a kind of presumptuous declaration that we have grasped life, its contours and limits. But what our faith is teaching us is that life is greater, vaster than anything we can encapsulate. And that's why it says that life has changed, not ended. That thoroughly mysterious, profound, God-given and God-destined gift called "life" has changed gear, entered some other level of existence or expression. This, for me, is the most euphoric, most stupendously audacious teaching of the Church, and it's not just speculation: it's based entirely on the belief of St Paul and

the early Christians: our life on this earth, while grand and miraculous, is not the whole story, and there is some state even more glorious awaiting us. Paul used the image of the "spiritual" body, Jesus used the image of the eternal banquet, but it's all really a mystery. Can we understand this? No. Is there any proof? Again, no. But we don't require proof, only faith, belief.

A native of Limerick city where he went to school in St Clement’s College, Fr Colm Meaney CSsR first went to the Philippines as a student and has spent most of his priestly life there.

Are you enjoying this issue of Reality?

Would you like to receive Reality on a regular basis?

ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION* ONLY €25/£20

Taking a subscription ensures Reality magazine is delivered to your door every month instead of calling to a church or a shop in the hope that you will find it there. Each issue is packed with articles to inform, inspire and challenge you as a Catholic today.

A one year subscription to REALITY magazine is just €25 or £20

No extra charge for postage and packing

HOW TO ORDER: Phone 01 492 2488 • Email sales@redcoms.org • Online www.redcoms.org Post Complete the order form below and return it to:

Redemptorist Communications, St Joseph’s Monastery, Dundalk, Co Louth, A91 F3FC ORDER FORM:

Yes, I would like to subscribe to REALITY.Please send me a copy of ‘VISITS TO THE BLESSED SACRAMENT’ PAYMENT DETAILS | Please tick one of the following options:

FREE!

With every subscription

OPTION A:

I wish to pay by credit card

VISA MASTERCARD LASER Valid from: Valid to:

CVC

OPTION B:

OPTION C:

Name

I wish to pay by cheque

I enclose a cheque for:

Existing account holders only: Please bill my account at the address below.

My account number is: PLEASE NOTE THAT CHEQUES MUST BE MADE PAYABLE TO “REDEMPTORIST COMMUNICATIONS”

Phone

FAMILY & RELATIONSHIPS

CARMEL WYNNE

CHILDREN LIVE WHAT THEY LEARN

THE COVID CRISIS CONTINUES TO PUT A STRAIN ON FAMILY RELATIONSHIPS. IT ALSO SHOWS IN STARKER COLOURS ASPECTS OF PARENTS' RELATIONSHIPS THEY MIGHT PREFER TO KEEP UNDER WRAPS.

During lockdown in summer 2020, children learned lessons about couple relationships they would never have learned in school. It’s understandable that even the best-matched, happiest parents found social isolation and lockdown difficult. The Covid crisis put a strain on family relationships and also on marriages.

Deprived of the usual methods of relieving tension, husbands and wives were challenged to face the reality of the state their marriage was in. Children could not go out to play or go to school. Adults had to work from home. No one could go to the gym, meet their friends, play sports or do whatever it was they used to do to vent and feel better when they were frustrated and in need of personal space. Home truths emerged when families had no access to what they normally did to relieve stress.

Some busy people had the habit of only talking to each other about practical matters or work. Couples, who were married a long time, were often unaware of how far apart they had grown. On the surface they apparently had a good marriage but it was friends and family who gave them emotional support.

When parents are angry, frustrated and resentful of each other, the atmosphere in the home is toxic. Children sense when parents are not getting on, even if they never see mum and dad fight. Over the months of social isolation, family members fought more. Spouses could no longer

walk away when issues, which had been present in the marriage and were not resolved, came up time and time again.

Counsellors tell us that people who do not talk about what really bothers them, nag. For example, a woman constantly complains about her husband’s habit of leaving wet towels on the bathroom floor. The real issue she is not telling him about is that she resents his expectation that she is the one to clean the house, when both of them are working and she feels overwhelmed.

Lack of honest communication blocks couples from having the easy-going, warm, affectionate conversations they used to enjoy. A husband, who knows something is wrong, has no idea of how to make it right if his wife won’t talk about what is bothering her. Stress builds up if spouses ignore or deny the issues that generate negative, hurt feelings. Constant nagging, blaming, complaining, failing to say ‘thank you’, walking away and not apologising are signs that things have gone badly wrong in a marital relationship.

Emotional, practical and financial support are essential for a loving and enduring relationship. Practical support involves helping with household tasks like gardening or putting the bins out. When either spouse is unwilling or unable to give the other the emotional support s/he needs, a marriage is in trouble.

Mary was married to a street angel and house devil. Her husband John had regular tantrums and never apologised. If she didn’t go along with what he wanted, he got in a rage. Clever with words, he twisted everything and had her doubting herself. He made hurtful remarks, and then denied what he said or told her she was over-sensitive. If she cried, he told the children that she got upset over nothing and couldn’t take a joke. He lied about things that he had no need to lie about, things which were easily verifiable. One of his favourite sayings was, “I’m right, you’re wrong, even when I’m wrong, I’m right.”

A successful businessman, John was intelligent, charming and outgoing. He was so busy with work and travel that he made up for not spending time with the children by buying them expensive gifts. The disruption to his business schedule during lockdown was particularly stressful and difficult.

The social isolation was hard for the whole family. Mary was used to John taking his frustration out on her but the strain he was under took his anger to fever pitch. The children saw a very different side to their father when he lost his temper with them. He dragged up things that had happened in the past and blamed everyone but himself for the grievances and complaints that fuelled his anger. As the outbursts with his children became more 31 frequent and progressively more nasty, cruel and spiteful, Mary had a ‘lightbulb’ moment.

She allowed herself to be mistreated because she valued the financial and practical support John gave her. Mary knew that John lacked empathy. She made excuses for how he treated her and his sense of entitlement. He never showed appreciation or said 'thank you'.

While their critical powers were still in the process of development, John and Mary’s children observed parental behaviour which demonstrated a lack of empathy as well as the absence of good relationships skills. Children live what they learn.

Carmel Wynne is a life and work skills coach and lives in Dublin. For more information, visit www.carmelwynne.org

A TRUE PRIEST IS NEVER LOVED

RICHARD POWER’S THE HUNGRY GRASS

IT APPEARED MORE THAN HALF A CENTURY AGO, BUT RICHARD POWER’S NOVEL, THE HUNGRY GRASS, MAY STILL HAVE MUCH TO TELL US ABOUT CONTEMPORARY IRELAND, ITS PRIESTS AND PEOPLE.

BY EAMON MAHER

First published in 1969, Richard Power’s second novel, The Hungry Grass, is an empathetic portrayal of the life of a priest in rural Ireland. The novel has a nostalgic resonance for those of us living in what many perceive to be a post-Catholic society. By ‘post-Catholic’, I don’t mean that all traces of Catholicism have disappeared in this country, but rather that it no longer exerts an all-pervasive influence on people’s lives. Indeed, it is now just one of many options 32 available to those seeking spiritual nourishment. With the decline in the fortunes of the Catholic Church, diocesan priests in particular have had a torrid time of it, with their smaller, largely elderly cohort forced to work harder and longer in order to meet the needs of their parishioners. The reputational damage done to the Church in the wake of the clerical abuse scandals has been focused in the main on the hierarchy, which is viewed as having been interested primarily in preserving the institution at all costs. Priests working on the ground are still held in high esteem, generally speaking. They are the ones who care for the sick and the vulnerable and who officiate at ceremonies associated with joy and pain, such as baptisms, weddings and funerals. They are on the front line when it comes to dealing with the public and have borne the brunt of the people’s anger in relation to the abuse scandals. One of the priest characters remarks at the start of The Hungry Grass that “A true priest is never loved”, a comment that is attributed to the French Catholic novelist Georges Bernanos, whose Diary of a Country Priest is one of the most memorable fictional accounts of priestly ministry ever written. Whereas Power never quite succeeded in matching Bernanos’ probing of the inner workings of a priest who considers himself as a lamentable failure but whose actions lead people to consider him a saint, The Hungry Grass nevertheless allows us access to a compelling central figure in the form of the main protagonist, Fr Tom Conroy.

A FLAWED MAN

Power’s hero is in many respects a flawed man, someone whose sharp tongue inspires fear in several of his fellow priests and parishioners. He is regularly irascible and intolerant, especially when it comes to his dealings with his curate Farrell, whose enthusiastic embrace of the changes introduced by Vatican II, especially the concept of a priesthood of the laity, he dismisses as idealistic claptrap. He argues that the large number of the Sunday Mass congregation standing in the church porch, paying no attention to what is happening inside, demonstrate little aptitude for taking on such an apostolate.

He has also had a life-long enmity towards his uncle James, a self-serving politician who uses religion to advance his career, while blandly ignoring how he and his comrades in the IRA had been condemned from the pulpit during the War of Independence. James is typical of that revolutionary generation that came to power in the wake of Irish independence and conveniently abandoned the lofty ideals contained in the 1916 Proclamation. In John McGahern’s classic novel, Amongst Women, the disillusioned IRA veteran Michael Moran describes the fruit of their struggle in the following manner: “What did we get for it? A country, if you’d believe them. Some of our own johnnies in the top jobs instead of a few Englishmen. More than half of my own family work in England. What was it all for? The whole thing was a cod.” Fr Tom Conroy would share that assessment.

But Power’s character was not always so testy, as can be seen in his friendship with a feisty female Irish emigrant whom he visited during his time ministering in London. She did not see why she should pay the Catholic Church any dues, or show deference to its priests, and told him so on many occasions. And yet Conroy always felt comfortable and welcome in her home. Some time after he returned to Ireland, she sent him on 50 pounds, most likely because she appreciated the concern he demonstrated for her family and also because he did not sit in judgement of them. Conroy placed this money in the back of a cupboard with a bunch of other notes that he had accumulated during his working life and never spent — this significant stash is discovered by the executor of Conroy’s will in the days after his death.

A LIFE IN RETROSPECT

The novel begins with a description of Conroy’s last public appearance, a get-together of priests in Rosnagree, the parish in which he was born. The priests had been surprised at Conroy’s presence among them, as he was not generally a fan of such gatherings. He reminded them of “an emigrant returning to seek nourishment at his roots” and they had been struck by a perceptible softening in his demeanour. Ruminating on his life and career after his funeral, which, significantly, neither of his two living siblings attended, the priests recall how Conroy ended up in the seminary after his older brother Owen had decided the priesthood was not for him. At the end of his first year in the diocesan college, his academic prowess resulted in his being offered a place in Maynooth, which he refused, much to the surprise of everyone. He would subsequently be regarded as something of a maverick, a person of great intellect and suspected socialist leanings.

A great source of pain to Conroy had been how his family had treated his brother’s wife Marie after Owen died prematurely in London, leaving his widow to look after two young children on her own. The savings they had accumulated in the hope of buying back the home farm of Rosnagree were spent on the funeral – Owen’s youngest sibling Frank, who inherited the farm, noted all the expenses in his little notebook. Tom Conroy wants to restore their rightful inheritance to Owen’s children, but when he visits the Marie, now

remarried and settled in the south of England, to discuss his plan, he is told that they have no interest in having anything to do with the Conroys or their land. Afterwards, the priest realises how gauche he can be in his dealings with others.

Where Power’s character really excels is in his pastoral role. He has a deep appreciation of what a privilege it is to be in a position to comfort people in their hour of need. On one particular occasion, he is summoned to the house of an elderly parishioner, Kavanagh, to whom he administers Extreme Unction, now known as the Sacrament of the Sick. He puts the oil on the man’s eyes, ears, nose and mouth and reflects: “He had always thought it (Extreme Unction) was a sacrifice for the living, that every sacrament was for the living, to make them stand up and get on with it. Living was getting on with it. Once you stopped getting on with it, you were no use to God or man.” This is a good description of how Conroy sees his own role as a priest: he is not interested in great displays of power, preferring a non-showy, supportive form of priesthood. He too just ‘gets on with it’.

What intrigues the priests most in the wake of their confrère's death is the fact that one of the local farmers decides he wants to be buried in the plot next to Conroy’s, which prompts Fr O’Leary to remark: “No one around here would pay an extra bob unless they felt that Conroy had some … remarkable qualities….” They recognise that the locals must have sensed something saintly in Conroy or else none of them would have been prepared to expend money on acquiring an adjoining grave. The priest himself certainly does not feel he has achieved anything exceptional: “In his whole life, in fact, had he ever done anything that was not futile, anything strong that would last?” We are not always in the best position to determine what legacy we leave behind. Certainly, Conroy was too critical of himself in this instance, as he had done good things in the course of his life, along with some bad things, which is only human. Declan Kiberd praises The Hungry Grass for breaking with what he describes as “the saccharine depictions of the Irish priest, that ‘soggarth aroon’ beloved of 19th-century novelists and 20th-century Hollywood movies”. Power eschewed any attempt to make a saint out of Tom Conroy and yet one detects from the priest’s lucidity about his past actions and his desire to make amends that he was at worst someone with serious failings, and at best, an inherently decent man. The last lines of the novel leave us with the impression that he had at last found some peace: “And Father Conroy plunged forward into the laughter and talk with an eagerness he had never known, not even when he drank the wine and broke the bread of life.” What happens beyond the grave surpasses the competence of the novelist or the theologian, but one suspects that it may well have proved positive for this largely unloved and misunderstood priest.

Eamon Maher is director of the National Centre for Franco-Irish Studies in TU Dublin. His latest book, co-edited with Brian Lucey and Eugene O’Brien, Recalling the Celtic Tiger, is published by Peter Lang, Oxford.

A Redemptorist Pilgrimage

Visiting the sites associated with St. Alphonsus & St. Gerard in Southern Italy Saturday May 8th to Saturday May 15th 2021.

Based at the Caravel Hotel in Sant’Agnello, Sorrento (Half Board)

Cost: €1,095.00/ £985.00 per person sharing. Places are limited so early booking is advised.

Group Leader: Fr Dan Baragry CSsR

For further details contact Claire Carmichael at

ccarmichael@redcoms.org Tel: 00 353 (0)1 4922488

The Irish Nun who nursed Pope Francis as a baby in Buenos Aires

AS AN EMIGRANT WOMAN STRUGGLING TO MAKE ENDS MEET, REGINA MARIA BERGOGLIO WAS FORTUNATE TO HAVE THE HELP OF A LITTLE SISTER OF THE ASSUMPTION IN CARING FOR HER INFANT SON IN THE FIRST DAYS OF HIS LIFE. IT WAS THE BEGINNING OF A CLOSE FRIENDSHIP BETWEEN THE SISTERS AND THE BERGOGLIO FAMILY, ESPECIALLY BABY GEORGE, NOW POPE FRANCIS.

BY MATT MORAN

The visit of Pope Francis to Ireland generated a lot of media coverage, but one significant historical connection he had with Ireland was overlooked. That connection was with an Irish missionary nun from Co. Cavan – a member of the Little Sisters of the Assumption.

NURSING SISTERS

The Little Sisters of the Assumption were founded in France in 1865 by Fr Etienne Pernet and lay woman, Antoinette Face, in an effort to ease the misery of urban impoverishment among poor and workingclass families.

Sr Oliva Maria (Susan Cusack)

The Sisters arrived in Buenos Aires in 1910, and from there spread out to other countries in Latin America. In 1932, a second community was established in Flores which was comprised of working families and many immigrants. One of these families was the couple, Jose Bergoglio and Regina Maria Sivori who were Italian immigrants. When their first child – Jorge Mario (now Pope Francis) – was due to be born on December 17, 1936, they sought the help of the Little Sisters. That help was provided by Sr Olive Maria who stayed with the family for a week caring for the mother and her baby boy. Little did she realise then that the baby boy would grow up to be the pope and leader of the Catholic Church which she, as a young girl, had left Co Cavan to serve on the missions.

FROM CAVAN TO ARGENTINA

Sr Oliva Maria was born Susan Cusack on January 1, 1889 to Philip and Ellen Cusack (nee Donohue) in the parish of Crosserlough near Kilnaleck in south Cavan. She was one of four girls along with Mary, Ellen and Kate, and two boys, Thomas and Phil. The family lived on a small farm. She was baptised in Crosserlough’s St Mary’s Church which had opened in November 1888 and attended St Mary’s National School which opened in 1886. Toddler Jorge

Susan joined the Little Sisters of the Assumption at Grenelle in Paris on October 30, 1909, and was professed on May 23, 1912. She served in Reims and Saint Etienne until 1923 when she was assigned to South America ministering first in Buenos Aires. In 1933, she moved to Flores where she encountered the Bergoglio family. In 1963, she moved to Rosario for one year, and then to Montevideo for four years. She spent her final seven years in Muniz, near Buenos Aires, where she died on October 31, 1975, and is buried there. A number of relatives still live in Co Cavan. Sr Oliva was mentioned in Crosserlough through the Ages – a book on local history which was published in 2013.

IN THE FAMILY OF A FUTURE POPE

When a girl was born to the Bergoglio couple in 1937, Argentinan Sr Antonia Ariceta cared for the mother and baby and the then one-year old toddler. The parents and grandmother were active members of the Fraternity and of the Daughters of St. Monica – support groups of laity that were very dynamic with the sisters in the Flores community. Men joined the Fraternity and women joined the Daughters of St. Monica. In the context of today’s discussion about involvement of women and laity in general

Jorge and his brother

in church activities, it is noteworthy how this and many other congregations have had very active involvement for centuries. Today in Ireland, the Little Sisters of the Assumption have a significant number of lay volunteers supporting their missions in South America. "My father and my mother talked to us about the Little Sisters,” Pope Francis said. “They used to go zealously to houses where there was a woman who needed to be helped with the housework, prepare the children to go to school, and so on. A poor woman who could not pay for this help. As poor servants they used to make a deep impression on me always. From time to time my father or my mother, but more often my father, used to take us to visit them in the Calle Junta. When it rained heavily this street used to be flooded and we had to cross over by a bridge. In the district, they were called 'the Little Sisters of the bridge' because of this bridge that had to be crossed."

KEEPING CONTACT

Pope Francis kept up close contact with the Sisters and, after he was appointed Archbishop of Buenos Aires, he used to visit Sr Antonia and the La Inmaculada community regularly, keeping up a fraternal contact. When Sr. Antonia celebrated her diamond Class group with Jorge in the front row, extreme right

jubilee in January 1999, he celebrated the

Eucharist in the community’s house.

He often visited some Sisters who worked

in the hospital for infectious diseases. His

pastoral or spontaneous visits to the families

were marked by special attention to the

sick, especially the poorest and weakest.

On August 15, 2010, he presided at the

celebration for the centenary of the arrival of

the Little Sisters in Argentina – an event which

was attended by an Irish representative of the congregation. Jorge Mario kept, as something very precious, the cross that used to be given to the 'Monicas' and

which had belonged to his grandmother. On one occasion he mentioned that he kept it beside his bed, saying "it is the first thing I see when I wake up".

Sr Annette Allain, LSA coordinator in the USA, stated during the papal visit to their community in East Harlem, New York in September 2015: “Pope Francis has a first-hand appreciation of our mission and spirituality from an early age due to receiving home care services from the Little Sisters of the Assumption and also from the involvement of his parents and grandparents in our support groups. It is my belief that his sensitivity to the poor and immigrant population grew from his own personal familial experience. We have been called to become family among the very people Pope Francis loves – those living on the margins of society. This is a privileged encounter of mutuality, believing that the power of growth is in relationship. There is no greater gift than Pope Francis’ visit to East Harlem as the Little Sisters of the Assumption celebrate our 150th anniversary.”

In his foreword to the book Il Vangelo guancia a guancia (The Cheek to Cheek Gospel), published in March 2018 by journalist Paola Bergamini, which tells the life of Fr Stefano Pernet, Pope Francis wrote: “I have many memories tied to these religious women who, as silent angels enter the homes of those in need,

work patiently, look after, help, and then silently return to their convent. They follow their rule, pray and then go out to reach the homes of those in difficulty, becoming nurses and governesses, they accompany children to school and prepare meals for them.”

The Sisters say: “We like to share with friends and supporters the bonds that unite us to this priest who grew up in a family that shared the charism and the spirituality of our congregation and who now, by the will of God, is our Pope Francis.”

THE LITTLE SISTERS IN IRELAND

In 1880, the first community of the Little Sisters outside France was established in London at the request of Cardinal Manning. In early 1891, a community was established in New York, and was followed quickly by one in Dublin on April 4, 1891 at the invitation of Msgr Kennedy, chancellor of the Dublin Archdiocese. Eight years later, the congregation established a house at Grenville Place in Cork on May 28, 1899, and they still have a presence in Cork.

The Sisters arrived in an Ireland where there was great poverty, little or no state

aid, poor housing and widespread disease. In 2016, to mark their 125th anniversary, Carol Dorgan wrote a history of the Little Sisters in Ireland – To Tell Our Story is to Praise God. The book, which can be downloaded at www. littlesistersoftheassumption.org/celebrating125-years-in-ireland, gives an account of the Sisters’ arrival and the development of their work throughout Ireland and in the different places to which Irish Sisters went.

It is a social history of the Ireland to which the Catholic Church and religious communities, especially nuns in very large numbers, contributed so much with regard to education, health, and well-being of many generations of families when the state under British and later national rule could not provide such social services for citizens. The Little Sisters of the Assumption can be proud of their contribution to Irish society since those bleak days of 1891. Their number in Ireland is now just under 70 Sisters.

Matt Moran is a former businessman who served as board member and chair of Misean Cara, an Irish charity which supports missionary organisations. He is the author of The Legacy of Irish Missionaries Lives On, 2017.

Sr Oliva Maria with family members in Crosserlough, 1963

Jorge with his family

Jorge, the teenager

Jorge, the young priest

Clement

AND HIS FRIENDS

CLEMENT HOFBAUER HAD AN EXTRAORDINARY CAPACITY FOR FRIENDSHIP. IN HIS YOUTH, HE WENT ON PILGRIMAGES TO ROME WITH MEN WHO BECAME FRIENDS FOR THE REST OF HIS DAYS. AS A MEMBER OF A RELIGIOUS COMMUNITY, HIS FRIENDSHIPS WITH HIS COMPANIONS WERE SOMETIMES STORMY, BUT 37 ALWAYS FAITHFUL. IN HIS LAST YEARS, HE FORGED NEW FRIENDSHIPS WITH YOUNG AND OLD

BY BRENDAN McCONVERY CSsR

We have seen how Clement’s apartment in the chaplain’s lodgings in Vienna attracted young men and students. They were not the only ones who flocked to Fr Hofbauer. The simple priest, who had few pretensions to scholarship, soon found himself attracting the admiration of intellectuals, writers and artists, many of whom were part of the new Romantic Movement.

AN ALFONSIAN CONNECTION?

Clement was fortunate, when he came to Vienna after leaving Warsaw, to meet a man who turned out to have a connection to St Alphonsus. The administrator of the Minorite Church who offered Clement the position of hearing confessions there was Baron Josef von Penkler. Penkler had belonged to a lay group called Christian Friendship which had been founded by Niklaus von Diessbach, a former Jesuit. After the suppression of the Society of Jesus, Diessbach founded the Christian Friendship groups. Among other objectives, he promoted the writings of St Alphonsus. Clement probably knew Diessbach in his student days in Vienna, so it was a happy meeting for the two. They remained close for the rest of Clement’s years in Vienna and Penkler drew others to Clement. His position in the government was also a distinct advantage. It was probably a great joy for both of them when Penkler brought Clement the news that the Redemptorists were shortly going to receive royal approval and would probably be given their own church and monastery in the city. So close was the friendship between Clement and Penkler that Clement expressed the wish to be buried near him in the cemetery of Maria Enzersdorf. He was in fact buried there until his remains were transferred to Maria am Gestade , the first Redemptorist church he had fought so hard to obtain.

THE HOFBAUER CIRCLE

Many of them were probably brought together by a husband and wife, Frederick and Dorothea Schlegel. Frederick was born in Germany in 1772 into a Protestant family. He met Dorothea, the daughter of a well-known Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelsohn. Dorothea was at that time already married to a banker called Simon Veith with whom she had several children. She left Veit for Schlegel, and for several years, they moved from place to place around Europe. Dorothea initially

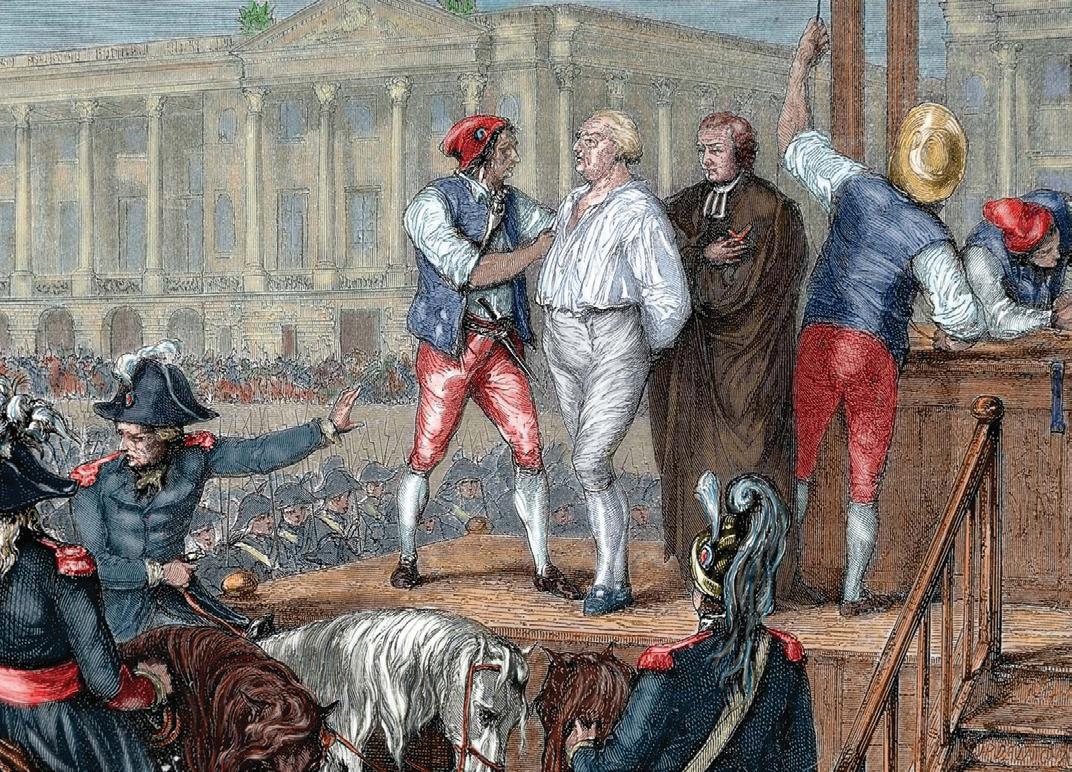

Left: Abbé Edgeworth

converted to Protestantism in order to marry Schlegel, but this unlikely couple both converted to Catholicism and settled in Vienna. It was there as recent converts that they met Clement in 1808.

They had the zeal of new converts when they met Clement and adopted him as their confessor. Their home became open house for a circle of Catholics who were tired of the old strictures under which the Church had survived for several generations and hoped that the end of the Napoleonic wars might be the sign of a new beginning. Clement was the ideal guide for a group like this. They became known as the Hofbauer Circle. It included influential people from the higher classes of society, from the literary world of the Schlegels and even some people in government.

Dorothea’s two sons from her first marriage, Johannes and Philip Veit, became Catholics in 1810. The young men were just about 20. It was Clement who prepared the young men for their entrance into the Church and Baron Penkler was their godfather. Both were beginning to show skill in painting. Eventually they both became members of a group known as ‘The Nazarener School'. It somewhat like the British Pre-Raphaelite movement, favouring bright colours and depicting narrative scenes. The ‘Nazarener’ label comes from its enemies who did not like the artists' reliance on biblical scenes or episodes from the lives of the saints. Clement is said to have joked with Philp that he made Our Lady in one of his paintings look like an elderly nun!

The members of the Hofbauer Circle were relatively few, but they saw themselves as sharing

The execution of Louis XVI

the same dedication to a renewed Gospel faith that motivated Clement. Clement’s influence was seen especially in students. “Quite a sensation was created, for example,” writes Clement’s biographer, Joseph Hofer, “when two lecturers highly esteemed in university circles openly renounced freethinking and not only became believing Catholics, but took up the study of Theology”. These two savants were Dr Emmanuel Veith, a Jewish professor of medicine, and Dr John Madlener, a mathematician. They would long remain members of Clement’s circle.

The state Josephism of Clement’s youth seemed to be on the wane and there was a renewal of the Catholic faith which was not merely intellectual but built on strong devotional foundations.

CLEMENT’S IRISH FRIEND

Clement’s most unlikely friend was a man who had been born in Co. Longford, and whose family gave their name to his birthplace, Edgeworthstown. Henry Essex Edgeworth was born into a Protestant landowning family. A relation was one of the first novelists, Maria Edgeworth. When he was four, the family moved to France after his father had converted to Catholicism. Henry studied for the priesthood and was ordained in Paris. He lodged at the house of the Missions Etrangères (foreign missions) in Paris, engaging in pastoral work in the city. His mother and sister lived close by in the Rue de Bac, a street that later became famous from its association with the miraculous medal.

When the French Revolution broke out in 1798 and with a growing hostility to the Catholic Church, Fr Edgeworh had to go on the run. He became confessor to Madame Elisabeth, sister of King Louis XVI. When the king was sentenced to death, the Abbé Edgeworth was asked to go to his cell on the eve of his execution in January 1793. He stayed with him all night, and in the morning, he said Mass for him in his cell. Then king and priest were driven through the howling mobs to the centre of Paris where the guillotine had been erected. The priest accompanied the king up the steps. As the blade crashed down, Fr Edgeworth was splashed with the king’s blood. He managed to disappear into the crowd, and for the next three years he was on the run, never staying any more than two nights in the same place. He eventually made his way to England when what remained of the French royal family escaped to Warsaw and then Mittau in Lithuania.

Clement probably met Fr Edgeworth in Warsaw. In a long letter to the Nuncio in Vienna in May 1802, Clement gave an account of his troubles. He complained that he had no one he could turn to for advice. He referred to his friendship with Edgeworth, “my most intimate friend and to him I do not hesitate to lay open my whole heart” but sadly, he had left Warsaw. A couple of years later 39 things had become so unbearable that Clement seriously considered leaving Europe for good and founding a Redemptorist community somewhere in North America. He realised the difficulties that would raise, but thought his friend, the Abbé Edgeworth, might be of some help. When he wrote to him, Abbé replied that he was not in favour of Clement giving up his works in Europe. He compared him the man in the parable: “Because for three years you have sought fruit on this fig tree, do you now wish to cut it down?” and urged him to stand firm. Nevertheless, he enclosed a letter of introduction to Lord Douglas that Clement could use if necessary. He concluded: “be reassured that whatever you decide to do, my love will follow you.” In the event, Clement decided to put thoughts of America aside. Fr Edgeworth died at Mittau from typhus contracted from ministering to wounded French soldiers after the Battle of Eylau in 1807.

Fr Brendan McConvery CSsR is editor of Reality. He has published The Redemptorists in Ireland (1851 – 2011), St Gerard Majella: Rediscovering a Saint and historical guides to Redemptorist foundations in Clonard, Limerick and Clapham, London.

UNDER THE MICROSCOPE

We Remember Maynooth

A College Across Four Centuries

Edited by Salvador Ryan and John-Paul Sheridan

Messenger Publications Dublin 2020 Hardback. 512 pages €50 ISBN 9781788122634

Founded in 1795 by an Act of Parliament of King George III to promote the “better education of persons professing the popish or Roman Catholic religion", Maynooth College has played a significant role in the history of the Irish Catholic Church, and through its graduates, an equally notable one in the Catholic Church on all the continents. To mark the 225th anniversary of its foundation, the members of the faculty of theology have sponsored this rich volume of essays. The campus of Maynooth is probably unique among educational establishments anywhere in that it is the home to two distinct universities. The older of the two, the Pontifical University, was established in 1896 to mark its first centenary and with the right to grant degrees in philosophy, theology and canon law. In 1910, it became a constituent of the National University of Ireland, granting degrees in the arts and sciences. In 1997, this became the independent Maynooth University, alongside the smaller, but independent, Pontifical University for the theological sciences. The students of the two colleges, male and female, clerical and lay, share a common patrimony in the architecture, the personalities and the stories which make Maynooth an attractive and memorable place to study and undertake research.

The first layer of this rich collection draws on the history of Maynooth. Its roots in the University of Paris, the Sorbonne, through its first generation of professors, is remembered in the Pontifical University’s distinctive continental style of academic dress of toga and epitoga. Donal McMahon, who taught for many years in the seminarist programme, remembers some of that generation, such as Professor Louis Delahogue who celebrated his 73rd birthday on January 16, 1812 by an address to the students on the occasion of announcing the examination results. In another essay he describes the relationship of two English writers and contemporaries, John Henry Newman and William Makepeace Thackery, to Maynooth. St John Henry Newman had already registered his debt in his Apologia pro Vita Sua to a young Maynooth professor, Charles William Russell, after whom the college’s Russell Library is named. When it was rumoured that Queen Victoria might visit the college in the course of her Irish visit of 1849, an address of welcome was prepared. Archbishop McHale of Tuam protested that if such a thing were to be presented, it should clearly state “the terrible suffering of her subjects, as well as of the cruel neglect with which they have been treated by her ministers”. Half of the bishops in fact refused to sign the address which has been prepared, so it was probably politically fortunate the college was not included on the itinerary.

One of the most notable of the members of the college teaching staff was Nicholas Callan (1799-1864) whose story as a pioneer in the exploration of electricity and the inventor of the forerunner of the battery is told by Niall McKeith. The rather crude-looking instruments he invented for his research are still preserved in the college museum. Although regarded as a mild-mannered and devout man, Callan believed in ‘active class participation’. On one occasion, he showed the dangerous power of electricity by electrocuting a turkey: on another, intended to demonstrate how people could transmit shocks to each other when part of an electric circuit, a future Archbishop of Dublin passed out from the shock! No teacher today could dare attempt such experiments for health and safety reasons! Recent members of staff like Dr Brendan Devlin and Pat Russell tell here the story of their own efforts to build up departments of French and German from slender resources to meet the international standards demanded by a modern university. Others recall colleagues such as Fr Peter Connolly who was a wise and moderate voice in the debate about censorship in which the Catholic Church (and Maynooth in particular) is often presented as the villain. The college is scarcely known for space exploration, but Dr Susan McKenna-Lawlor describes her academic participation in the European Space Agency’s 'Giotto Mission'. Music has been a noteworthy presence in Maynooth and it is right that it should receive attention in several articles. The first, by Darina McCarthy, records the musical contribution of Heinrich Bewerunge (1862-1923) to the reburial in the college cemetery of the Irish scholar Eugene O’Growney. Bewerunge was a German priest professor of the subject whose career was unfortunately cut short by the First World War. John O’Keeffe sketches how that tradition has been nurtured and borne fruit in the modern vernacular liturgy. Fr Liam Lawton, a composer of liturgical music, describes ‘finding his voice’ in Maynooth. Patrick Devine in ‘Play it Sam’ pays tribute to Fr Noel Watson, whose association with the annual college carol service is described by Gerard Gillen, himself a former professor of music in the college. Fr Hugh Connolly describes the rebuilding of the organ, while Archbishop Eamon Martin of Armagh describes taking part in the French tour of the college chapel choir.

Maynooth will of course be remembered for its human face. It is interesting to note the names that recur over several contributions – Frank Cremin, Ronan Drury, Tomás Ó Fiaich who have gone to their reward as well as those who still remain with us. These faces are not just clerical ones. They include the first women on the teaching staff while the first lay professor 'An Chéad Ollamh Tuath', Anthony O’Farrell, recounts his own interview process and appointment. Many of these human faces adorn the walls of the college in the form of the ‘Class Pieces’ which are surveyed here by JohnPaul Sheridan, one of the editors of the volume. The current president describes a ‘Teetotallers’

Rebellion in the Professors’ Dining Room’ in the early years of the 20th century. Colleges, especially residential ones like Maynooth, cannot survive long without food. For many years, the farm made it self-sufficient . David J. Carbery shares some of his memories of Maynooth catering. Michael O’Riordan took up his position as a boy of 15.

The Sign Reading the Gospel of John

by Seán Goan

Dominican Publications Dublin 2018 128 pages €12.99 Seán Goan has studied scripture in Rome and Jerusalem. The cover shows us the apse of San Clemente owned by the Irish Dominicans. John, he says, is different from the other gospels. There are no miracles, only signs. As an example, I will take you through the story of the wedding of Cana and show how profound is the symbolism involved.