Escaping Slavery: an excerpt from the forthcoming novel “Blood Grip” p. 26

Advocates, City Council and the School District of Philadelphia get the lead out of our children’s drinking water Are schools preparing students for climate change? p. 16

THE COMMUNITY AND EDUCATION ISSUE

Michael Ferrin Woodworker and Artist Philadelphia, PA michaelferrin.com

TELL US ABOUT BUSINESS + YOUR STORY

I grew up in South West Philadelphia. My father is a luthier and when I was a child he repaired instruments for the Philadelphia School District while he took care of me - he clamped my baby seat to his workbench. In my work, I am interested in environmental and social justice, helping to further diversity in the woodworking community, and exploring how my work fits into the history of craft.

WHAT ARE YOU CURRENTLY WORKING ON?

As the Winter Resident at the Center for Art and Wood x NextFab, I am using khatam marquetry to explore themes related to Philadelphia’s Muslim community, using designs borrowed from SEPTA subway station tiles to represent the importance of public transit to the city’s residents and develop techniques for producing khatam more efficiently than I have previously been able to. Khatam is a technique from Iran that uses very small triangles of wood, metal, and bone to create geometric patterns. Traditionally the wood would be carefully selected from several species of trees in order to obtain a variety of colors. I’m using reclaimed wood from broken furniture, pallets, and cabinet shop off-cuts to achieve a variety of colors.

@ferrin.woodworking

@ferrin.woodworking

nextfab.com/blog

FEBRUARY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 1 Parka Fridays? Not the best way for your business to save. PECO has energy answers. Saving money is easier than you think with advice that leads to comfort and energy savings all year long. Learn more ways to save at peco.com/waystosave. © PECO Energy Company, 2023. All rights reserved.

publisher Alex Mulcahy director of operations Nic Esposito associate editor & distribution Timothy Mulcahy tim@gridphilly.com

copy editor Sophia D. Merow art director Michael Wohlberg writers Bernard Brown

Constance Garcia-Barrio Lindsay Hargrave Bryan Satalino Ben Seal photographers Chris Baker Evens illustrators Abayomi Louard-Moore Bryan Satalino published by Red Flag Media 1032 Arch Street, 3rd Floor Philadelphia, PA 19107 215.625.9850

GRIDPHILLY.COM

Fountain of Truth

Don’t give up on Philadelphia just yet.

Our centuries-old city has big problems, including the legacy of lead. It’s in our paint, our pipes, our bloodstreams. When it gets in our children, it hurts their young brains’ development, negatively affecting learning and behavior.

With the district-wide installation of hydration stations — filtering units that remove lead (among other things) from water in the schools’ fountains — the efforts of activists, bureaucrats and politicians have resulted in a major public health victory.

As we are overwhelmed by news about problems with no easy solutions, we should rejoice in this triumph, and learn from it as well.

Helen Gym, a former councilmember now a candidate for mayor, says: “When we are clear about our missions, we can go out and leverage resources to make it happen.”

Intractable problems require unshakeable resolve. We must set the moral compass, something our City government has struggled to do, and then get to work.

One place we can and must set the agenda is in the classroom. Not only do we have the responsibility of protecting our kids from the poisons of our industrial legacy: we must also prepare them to care for the damaged planet they will inherit. Yes, it’s sad and unfair that we lay this at their doorstep, but hiding the truth worsens the crime and delays progress. In 2020, neighboring New Jersey became the first state to mandate learning standards that require teachers of all classes (even gym!) and grades to integrate climate change into their curriculum. While it’s encouraging that the School District of Philadelphia is offering training for teachers interested in teaching climate change, the training is voluntary, as Ben Seal reports (“Learning Environment,” p. 16), which guarantees that it will not reach everyone.

Although the reality of climate change is grim, it can be taught in ways that empower and give hope. As Grid writer Bernard Brown shows in his piece “Beyond these Walls” (and in greater detail in his mustread book “Exploring Philly Nature,” where he urges us to open our eyes and see that “habitat is everywhere, and everywhere is habitat”), cultivating the connection between kids and their surroundings enriches their lives and teaches them to care. Let them fall in love with the world they must save.

Speaking of excellent books from Grid contributors, I am honored to share with you on page 26 the opening chapter in Constance Garcia-Barrio’s debut novel, “Blood Grip.” I was fortunate enough to get an early manuscript, and it is magnificent. It’s a harrowing story of a Black family escaping slavery to start a new life in Philadelphia and the unspeakable adversity they face. The story is riveting, the characters nuanced, the language lyrical. Even in the most heart-wrenching scenes, there are turns of phrase that delight. It’s Grid’s first foray into fiction, and she has set the bar high. It pairs well with Garcia-Barrio’s story (nonfiction, alas) about the historical exhibition of Black bodies (“Cruelty on Display,” p. 6).

My hope is that one day Garcia-Barrio’s stories and others like it are taught in every school, too. All kids need to know the truth. It’s the only way things will change.

EDITOR’S NOTES by alex mulcahy

ILLUSTRATED PORTRAIT BY JAMES

2 GRIDPHILLY.COM FEBRUARY 2023

alex mulcahy , Editor-in-Chief

BOYLE

FEBRUARY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 3 PLAN YOUR TRIP AT ISEPTAPHILLY.COM

Body and Soul

The husband-and-wife duo behind Urban Essence put a personal touch on skincare products

The husband-and-wife founders and owners of Urban Essence, Theresa P. Minor and Timothy L. Minor, know firsthand how spa and body care treatments can rejuvenate the skin and the soul. In 2003 Theresa was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. An IT professional, Theresa didn’t know if she was going to be able to continue working in that field — or if the crippling disease would rob her of her ability to enjoy everyday pleasures. At that time, there was one place where she could seek refuge.

“I always enjoyed going to get my hair done and those other types of services,” Theresa explains.

Newly focused on her health, Theresa realized that the products used in spa and salon treatments often contain petroleum-based chemicals. Leaning on her analytical background, she began researching the biology, chemistry and even technology used to create these products and realized that there was a more holistic and natural approach. Many of the products she wanted didn’t exist, however, so she convinced her husband, Timothy, to

do the next best thing — start their own salon and spa business.

Urban Essence Salon & Spa was founded the same year of Theresa’s diagnosis to bring quality body care products to men and women in the Philadelphia metropolitan area. At first they started working with a manufacturer to create the soaps and lotions and had plans to open a physical spa location. But staying true to Theresa’s vision of ensuring that they had full control over what went into their products, the couple decided against opening a physical location and to focus instead on manufacturing the products themselves.

“I basically taught myself,” explains Theresa. “I took classes, did research and did anything I could to make the product better.”

Timothy found that focusing on the product and scaling the business deliberately offered great advantages.

“Being a husband-and-wife team allows us to contribute 100% of ourselves to the business,” says Timothy. “And being small allows us to reach people and have more interaction.”

Some of Timothy’s favorite moments are when a person will come up to them at one of the various farmers markets where they sell their products, pick up a bar of soap, ask about the ingredients and then take a deep sniff of the bar and say, “Wow, this smells just like what my grandmother used to use.” Timothy describes an almost transcendental experience when he can actually feel the emotional connection that someone is making to an Urban Essence product.

In 2014, after over a decade of selling their products directly at farmers markets and in the community, the Minors decided to launch a wholesale program to, as Theresa puts it, “catapult their product into the Philadelphia region.” Despite being a self-described “shy person,” Theresa was walking past the Weavers Way Cooperative grocery in Chestnut Hill one day and there was just something about the store that inspired her to walk in.

“We had been thinking of going to bigger retail chains where you have to have a million meetings with different people before you get your product in the store,” Theresa recalls. “But at Weavers Way it was like, ‘No, you don’t have to do all that. Just give us a call and we’ll put you in.”

And it was that personal touch that really fit the Urban Essence brand and was a perfect match for the Minors. Timothy could immediately feel that Weavers Way staff shared this ethos.

“What people want you to show them is that we really do care,” Timothy explains. “Obviously everyone wants to make money. But with Weavers Way and their clientele, it’s like we’re partners.”

The success they have found selling their soaps at Weavers Way and other retailers has even allowed the Minors to support organizations they believe in, such as the National MS Society, Greater Delaware Valley Chapter. For Theresa, the ability to give back and run a great business is the most meaningful part of their work.

“There’s just something about turning these raw materials into a soap and actually watching the customer enjoy it. I love it.” ◆

4 GRIDPHILLY.COM FEBRUARY 2023 PHOTOGRAPH BY CHRIS BAKER EVENS GRIDPHILLY.COM FEBRUARY 2023

sponsored content

Urban Essence founders Timothy and Theresa Minor thrive on having a close connection to their customers.

FEBRUARY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 5

Cruelty On Display

A brief history of the business of exhibiting Black bodies for profit

by constance garcia-barrio

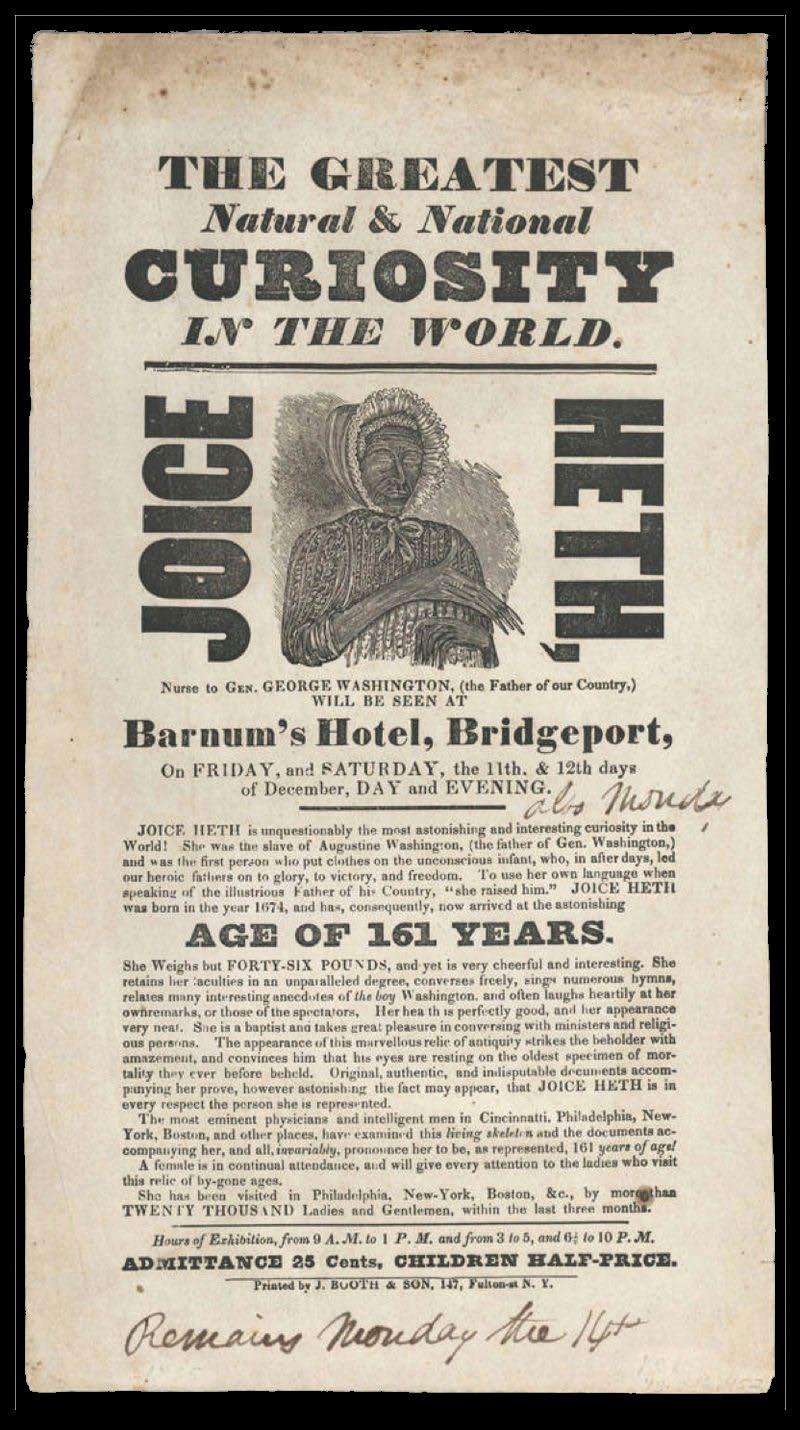

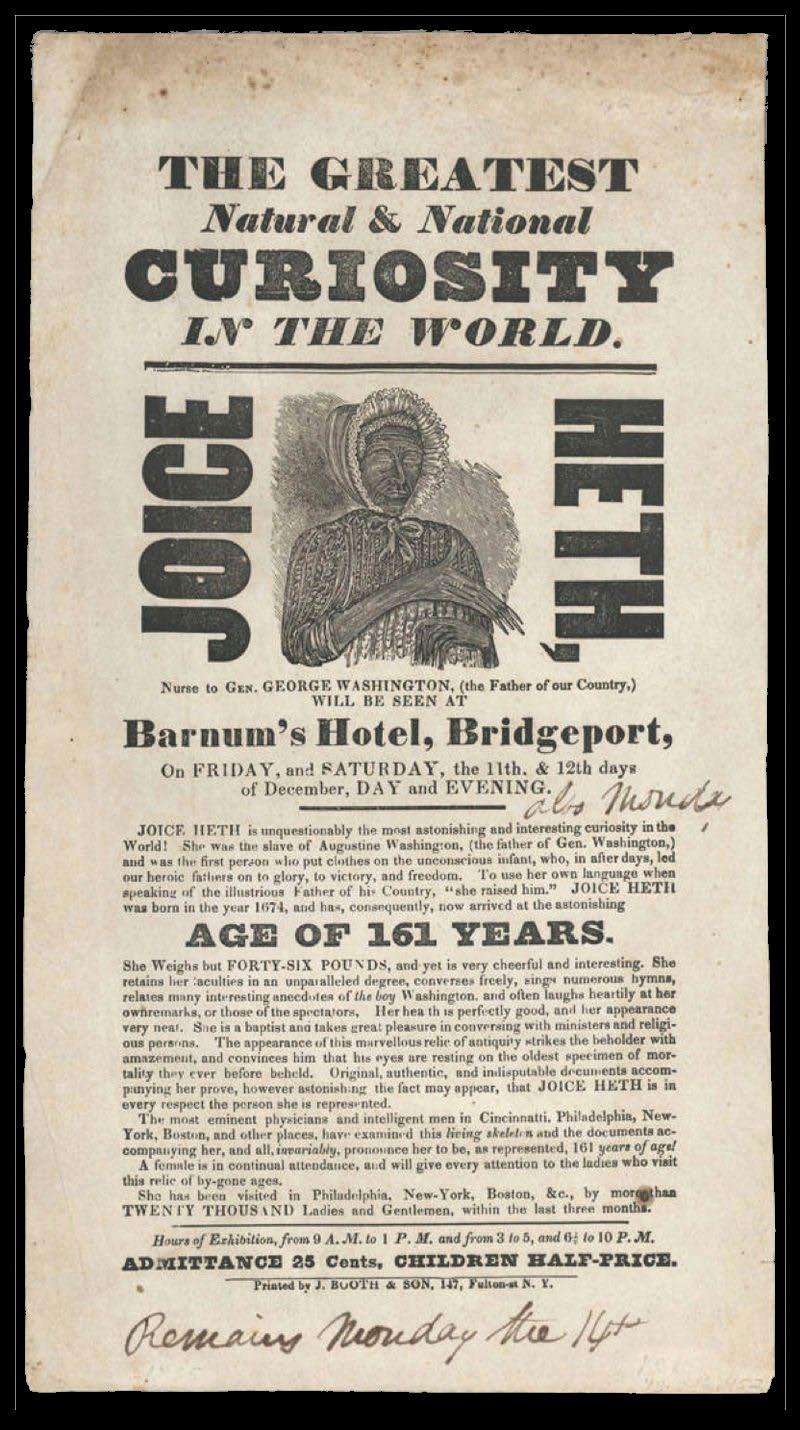

In 1835, future circus magnate P. T. Barnum and an enslaved Black woman he bought for $1,000 bamboozled the public, according to the impresario’s 1855 autobiography and Mark Bramble’s 1980 musical “Barnum.”

Barnum, living in New York, heard that the woman, Joice Heth, on exhibit in Philadelphia, claimed to be the 161-year-old former nursemaid of George Washington. Barnum rushed to Philly. He paid rapt attention as Heth assured all comers that she was once enslaved by Augustine Washington, George’s father, and that she was the first person to dress “little George,” Barnum’s autobiography says.

Heth’s claim hinged on her appearance.

“She looked as if she might have been far older than her advertised age,” Barnum writes. “She was … in good … spirits, but from age or disease, or both, was unable to change her position. Although she could move an arm, … her lower limbs were fixed in their position. She was totally blind, and her eyes were … deeply sunken in their sockets.”

Heth looked ancient, but seemingly not ancient enough for Barnum. Medical ethicist Harriet Washington says that he had Heth’s teeth pulled to make her look even older.

Even toothless, Heth chatted up the crowds.

“She would talk as long as people would converse with her,” Barnum writes. “She was quite garrulous about her ‘dear little George.’” Heth also sang hymns and smoked a pipe while on display.

Meanwhile, Barnum’s $1,000 investment brought in, on average, $1,500 a week — close to $50,000 in today’s dollars, estimates say.

Barnum’s exhibiting Heth sometimes

6 GRIDPHILLY.COM FEBRUARY 2023 PUBLIC DOMAIN SOMERS HISTORICAL SOCIETY

city healing

P.T. Barnum profited handsomely from exhibiting Joice Heth, an elderly Black woman who claimed to be George Washington’s nursemaid.

raised hackles.

“She is the sole remaining tie of mortality which connects us with … [George Washington] and as such, we should … not suffer her to be kept for a show ... to fill the coffers of mercenary men,” a reader complained to the editors of the New York Sun in August 1835.

When Heth died in February 1836 Barnum cashed in on her corpse. He charged 50 cents per person to attend the autopsy to establish her age. The surgeon who performed it declared Heth to have been 80 years old at most.

Heth, whose looks and gab made money, was paid nothing. Barnum, on the other hand, used cash he’d earned exhibiting her to launch his career in show business. After Emancipation, however, as the nation lurched toward civil rights, Black performers with unusual bodies flipped the script. They kept more of the money that their striking looks earned. Their lives included courage, talent, kidnapping, court cases and straight-up fraud. Like Heth, several performers had a Philadelphia connection.

*

Consider conjoined twins Millie-Christine McKoy (1851–1912), born into slavery in North Carolina. Fused at the tailbone, they shared a single pelvis and weighed a combined 17 pounds at birth, according to their biographer, Joanne Martell, in “Fearfully and Wonderfully Made.”

“At the time of our birth [we] were part of the family of a Mr. McKay,” the blacksmith who owned the twins, their siblings and their parents, Millie-Christine writes in “History of the Carolina Twins, Told in Their Own Peculiar Way,” a booklet one of the twins wrote at age 17. It sold for 25 cents at their performances. “Our coming [into the world] in such ‘questionable shape’ created a great furore in the cabin, as our appearance has [ever] since.”

Visitors who descended on McKay’s farm to see Millie-Christine included John Pervis, who paid McKay $1,000 for “certain twins negro [sic] girls about ten months old.” The twins and their family changed hands several more times, and Millie-Christine became separated from their parents, Jacob and Monemia. Finally, Joseph P. Smith bought the “Celebrated Carolina Twins,” “pert and cunning” toddlers by 1853, only to have them kidnapped. Smith hired a private eye to find them.

Meanwhile, the kidnapper laid low, giving secret showings of the girls.

He “gave private exhibitions to scientific bodies, reaping … a handsome income,” the twins’ autobiography says. “He took us to Philadelphia and placed us in a small museum in Chestnut Street, near Sixth, … under

the management of Col. Wood.”

In 1856, Smith got word that the twins’ manager at the time had them touring England. Determined to recover them, Smith bought the rest of Millie-Christine’s family. That December, he sailed to England with Monemia, the twins’ mother.

FEBRUARY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 7 HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF PENNSYLVANIA

As the nation lurched toward civil rights, Black performers with unusual bodies flipped the script.

This playbill promoted the McKoy twins as the “Eighth Wonder of the World and TwoHeaded Nightengale [sic].”

In January 1857 at the finale of one of Millie-Christine’s shows, Smith, an audience member and the American vice consul in London stormed on stage and wrenched the twins away from their manager, a Mr. Thompson. Bedlam erupted. Later, Thompson contested Monemia’s custody of Millie-Christine, but the English court ruled in Monemia’s favor.

Once back at Smith’s North Carolina home, Millie-Christine began performing under his management. Mrs. Smith helped polish the twins’ singing and dancing and broke the law by teaching them to read and write.

The Civil War stopped Millie-Christine’s touring. When it ended, the twins, 14 years old and free, began calling some shots.

“Now … [she] … set her own rules,” Martell writes. There would be “no more intimate examinations by curious doctors in every town.” In 1869 in Boston, Millie-Christine refused to let Harvard doctors do a physical examination of them. Later, they consented to a fully clothed visit to a Philadelphia medical school.

“In Philadelphia, Millie-Christine’s physician friend William Pancoast invited her to [a] teaching clinic at Jefferson Medical College,” Martell writes. “At age twenty-seven, Millie-Christine was of increasing interest to the medical community [because of excellent health despite being Siamese twins.]”

By 1882, Millie-Christine commanded $25,000 a season, according to an ad from the Great Inter-Ocean Railroad Circus, which featured them that year. That sum would have an estimated $727,000 of purchasing power today. Millie-Christine also presented their dancing and singing — one sang alto while the other sang soprano — in Europe for seven years, including command performances for British royals.

The twins bought the land where they were enslaved as children and built a 12room house on it. They also built a church, organized a school for Black children and donated to several Black colleges, according to a descendant. “One thing is certain,” their autobiography says, “we would not wish to be severed, even if science could effect a separation.”

*

One question bedeviled Ella Williams, aka Madame Abomah (1865–1925?), born mere months after the Civil War ended: Should

she remain a familiar oddity in Columbia, South Carolina, living near family and friends, with steady, low-wage work as a cook or join a circus as the world’s tallest woman, casting her lot with animal tamers, fire-eaters and tattooed wonders?

At 31, Williams, who probably stood between 6’9” and 7’4”, made up her mind.

In 1896, English entrepreneur and animal trainer Frank Bostock “offered her such terms [for performing in the British Isles] that she accepted the engagement,” says the April 4, 1905, edition of the Thames Star, a newspaper in New Zealand, one of many countries where Williams sang.

Newspapers followed her travels. An

Their lives included courage, talent, kidnapping, court cases and straight-up fraud.

Ella Williams, known professionally as Madame Abomah, toured South America, the Caribbean, Europe, the U.S. and Australasia.

8 GRIDPHILLY.COM FEBRUARY 2023 ARTHUR WINTER

article in the March 1, 1905, edition of New Zealand’s Wanganui Herald describes extraordinary accommodations made on the SS Afric for her trans-Pacific hop. It required “removing the bulkheads between two cabins [so she could lie down].”

Williams’s new status brought perks. “Abomah is not above … charming little [fashion] conceits,” said a November 24, 1904, article in The Mercury, a newspaper in Tasmania. “Abomah had plenty of lace … on the front of her blouse, two or three gold chains and rows of pearls.”

Australian promoters had to reckon with the country’s Immigration Restriction Act if they contracted entertainers of color, according to the September 10, 1904, edition of The Australasian. This act controlled the entry of Black and Brown persons into Australia. Promoters got exemptions for “the American giantess and the Fisk Jubilee Singers,” mentioned by name in the article.

At one point Williams had her own troupe. The Abomah Company of Entertainers included a ventriloquist, a magician and artists who performed “musical sketches.”

Williams toured South America, the Caribbean, Europe and major U.S. cities, including Philadelphia. She was performing in English music halls in 1914 when Britain declared war on Germany. She returned to the United States weeks before German Zeppelins bombed London.

Williams’s career spanned 30 years. A photo taken in 1925, the year of her last known appearance, shows her with Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey’s “Congress of Freaks” on Coney Island, thinner than in her heyday. No obituary has surfaced to tell when or where she died.

*

While Williams decked herself out for the public, Calvin Bird (or Byrd) wore a loincloth and a contrivance that seemed like an anomaly.

One story says that Bird, a tall “gingerbread-colored man” from Pearson, Georgia, got his start when he fell in with one of the four notorious Dedge brothers, doctors and dentists as well as murderers and counterfeiters from Georgia, according to the Ray City History Blog of April 17, 2013. John Dedge, D.D.S., born in 1865, was the most infamous of the clan. In 1901, Dedge and an associate concocted a plan to exhibit a “wild

man from Central America.”

Another version of the story says that Bird decided to be a “wild man” and drew Dedge into the plan. A Philadelphia dentist is said to have made a bridge with fangs that Bird used during his act.

Dedge claimed to have brought back a “wild man” from a trip to Central America. Newspapers ate up the story. “This freak is a man with two well-developed horns … growing out of his head. … He also has two prominent tusks … in place of eyeteeth,” said the Atlanta Constitution on May 8, 1902.

Another newspaper gave a wry response to Dedge’s claim.

“It is an off year in South Georgia when Dr. Dedge does not announce some astounding piece of freak work,” the Waycross Journal quipped.

It seems that Bird’s carousing revealed the fraud. Police in Valdosta, Georgia, arrested him for firing a pistol in the street, says the Waycross Weekly Herald of March 22, 1902. Police discovered that Bird had an incision in his scalp where a thin piece of metal had been slipped under the skin: goat horns could be attached to knob screws coming out of the metal strip so that the horns seemed to grow from his head. Likewise, his tusks could be fastened to his eyeteeth so that they appeared to grow from his gums. Bird swore that he didn’t know how the metal strip came to be under his scalp.

Bird had plenty of company playing a “wild man.” Black “wild men” who ran around in cages and gnawed horse meat upped circus profits and their own wages.

“Say you’re a roustabout and the boss offers you a chance to earn extra cash,” says circus historian and author Fred Dahlinger Jr. “What do you do?”

Bird and Dedge, unmasked yet undeterred, toured the country and raked in money. Finally, Bird turned up at the Hospital of the Good Shepherd in Syracuse, New York, and asked a surgeon to remove the metal plate from his scalp, according to William C. Thompson in “On the Road with a Circus.” “The Wildman business had got monotonous, he said and … he had made enough money out of his deception to maintain him in idleness for a long time.” *

Decades after the Civil War, Otis Jordan (1926–1991) from Barnesville, Georgia,

fought his own battle: He went to court to protect his right to be in sideshows. Born with a rare condition, arthrogryposis multiplex congenita, Jordan had small, ossified limbs and only two normal fingers. He reached a height of 27 inches.

“My brothers carried me to school … until I was in the fifth grade,” Jordan reports in the pamphlet “Life story of Otis Jordan.” With his father’s help, Jordan designed a little cart pulled by two goats so he could get around on his own.

As an adult, he “learned to drive a car with special controls and … [had] a valid license,” Jordan writes. “I am good at small appliance repairs and small crafts. However, it was impossible for me to get a job until 1963 when a small carnival played my hometown.” Jordan signed on.

He developed an act where he rolled and lit a cigarette using only his mouth and lips. He worked in sideshows until Barbara Bogdan, a handicapped woman, was outraged at seeing his act at the New York State Fair’s sideshow in the ’80s. Bogdan went to court to have the sideshow banned, but Jordan fought back and won.

“How can she say I’m being taken advantage of?” Jordan reportedly said. “Hell, what does she want — for me to be on welfare?”

Irony had the last word in the situation. Soon after the judge ruled in Jordan’s favor, he died of kidney disease. In addition, sideshows were fading from the scene.

Jordan’s case could start roiling debates about earning money by showing one’s unusual body. Whatever one’s opinion of the exhibitions of yesteryear, the arc of change stands out for Black performers, from Joice Heth who, enslaved, lacked choices, to Jordan, who stood his ground in court. Even today, some Black performers’ distinctive bodies — Lizzo, and model and actress Tatiana Lee, from Coatesville, Pennsylvania, born with spina bifida, come to mind — are part of their persona.

In this fraught slice of Black history, performers’ unique bodies get the spotlight, but whether their anomalies were real or fake, what carried the show was their lively minds. ◆

For more information, visit “The Uncle Junior Project, Celebrating the History of Black People in the American Circus,” online at unclejrproject com

FEBRUARY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 9

Bird Bussing

This spring students from five Philadelphia schools will go birding thanks to funding raised by the In Color Birding Club.

The club, launched during the pandemic by Upper Darby birder Jason Hall , commit ted to not only providing a space for adult BIPOC birders, but also offering a gateway to birding for local children.

Club board member Katrina Clark, at the time a teacher at The Workshop School, a School District of Philadelphia high school in West Philadelphia, suggested that the club help pay for buses. Thousands of students could benefit from field trips to local birding hotspots, she reasoned, but the district lacks the funds to pay for transportation. “One of the hardest things to get money for was a bus,” she says.

She had taken classes by bus to visit the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge thanks to funding from the Friends of Heinz Ref-

uge. Three members of In C olor Birding Club, including Hall, joined the Workshop School field trip. Clark spoke of the power of having her students, the majority of whom are Black, spend time with Black adults who are passionate about science and nature. “The students were spellbound, paying attention to every single word.”

While visiting the Heinz Refuge was a powerful experience, they needed to find funding that would help students visit other sites, which is of particular importance for schools located farther from the refuge in Northwest, North or Northeast Philadel-

phia. “We don’t ever want to have a field trip that will be limited due to cost,” Clark says. “I suggested to board members that we can make a difference paying for transportation.”

She estimated that $250 to $300 could pay for one bus, which transports about one and a half classrooms. Two or three buses can accommodate an entire grade from a school. “We can raise money and put that right out into getting teachers and students out.”

The club raised enough money for six buses and posted the application for teachers to apply in the fall of 2022. In January they awarded their grants to teachers from The U School (two classes), Thomas K. Finletter School, Frankford High School and Cook-Wissahickon School in the School District of Philadelphia and one private school, the Jubilee School in West Philadelphia.

Clark says that the club, which accepts donations on its website to support its educational work, plans to continue issuing school bus grants twice a year. ◆

10 GRIDPHILLY.COM FEBRUARY 2023 IN COLOR BIRDING CLUB

urban naturalist

Club funds transport for the next generation of birders by bernard brown

In Color Birding Club is committed to not only providing a space for adult BIPOC birders, but also offering a gateway to birding for local children.

The students were spellbound, paying attention to every single word.”

— katrina clark, In Color Birding Club board member

FEBRUARY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 11 PRESCHOOL THROUGH GRADE 12 | KIMBERTON.ORG 610.933.3635 EDUCATION THAT MATTERS Offering a holistic, experiential, and academically-rich approach to education that integrates the arts and the natural world every day REGISTER FOR UPCOMING EVENTS • Kindergarten Visit • Environmental Education • Discover the Lower School • Discover the High School

Beyond These Walls

to reinforce learning goals and encourage them to develop deeper relationships with the world outside.

Public

schools use their outdoor space to connect students with the natural world by bernard brown

Before she started working on the green schoolyard at Henry C. Lea School in West Philadelphia, landscape architect Sara Pevaroff Schuh, principal of SALT Design Studio, encountered a group of kids who called her over after finding what they said was a spider on playground equipment. It turned out to be a half-squished worm. She picked it up and dropped it in a planted area next to the playground. “And they’re shrieking their heads off because I touched the

worm.” A student promptly walked over and stomped on the unfortunate worm.

The incident highlighted the need for building a connection between students and the natural world. “You have some fundamental learning that needs to happen about the ecological world, not to mention the emotional issues tied up in being afraid of nature, the insects, any of the biota,” Schuh says.

Public schools throughout the Philadelphia area are using their schoolyards to engage students with nature in order

On Sunday, January 15, Penn Alexander School science teacher Stephanie Kearney and Craig Johnson of design firm Interpret Green (his chosen job title is “chief habiteer”) mounted a weather station in the school garden near 43rd and Locust Streets in West Philadelphia.

The weather station, consisting of an assortment of sensors set on a tripod, will collect real-time information on the conditions outside the school, all of which will be available for classroom learning as well as for researchers and advocates who can make use of a growing network of local readings from similar stations.

12 GRIDPHILLY.COM FEBRUARY 2023 PHOTOGRAPHY BY CHRIS BAKER EVENS water

This is not Kearney’s first venture into using technology to connect her students with nature. Kearney has worked with the Philadelphia Water Department to set up a bird nest box with a camera feed, as well as a soil moisture sensor.

Toward the end of 2020, as teachers adapted to virtual learning, she won a grant to buy game cams, motion-triggered, battery-powered cameras often used by hunters to study the movements of deer and other quarry. A raccoon roving during the wee hours might avoid notice by its human neighbors, but it will still trigger the game camera to take a picture.

“I’m big on applying for grants,” Kearney says, “and I got one for game cams. I ended up giving game cams out to students to put

them in their alleys and spaces in between apartment buildings. We got some of the usual suspects: raccoons, cats, squirrels, opossums.”

Kearney has been teaching her sixth-grade students about plastics pollution. “We are investigating not just how plastic is made but how it moves from the schoolyard out to the ocean and what we can do about it.” Her students collected local trash and analyzed it, finding that at least three quarters of it was plastic. “We talked about the combined stormwater system. Just today [Kearney spoke with Grid at the end of December] we got to the ocean, and kids will think about what they can do about the problem.”

Kearney won a grant from Toshiba America for the weather station. “We

had been talking for years about getting a weather station. Craig helped us put together a proposal for a full weather station — air quality and nest camera and bird feeders.” The weather sensors are the first phase, with the nest camera to follow.

This is not Johnson’s first time working with teachers to exploit the potential for learning in their schoolyards. In 2016, for example, the Delaware Valley Green Building Council (now Green Building United) gave a Groundbreaker Award to Interpret Green’s Lots-To-Learn green schoolyard project at William Cramp School in North Philadelphia. Lots-To-Learn incorporated several of the same elements Kearney is setting up at Penn Alexander, all tied into the school curriculum.

“Putting up a birdhouse and seeing a bird fly in and then lay an egg, [students] don’t have to be looking at an eagle’s nest in Seattle,” Johnson says. “They can walk outside and say, ‘It’s right there.’” The same goes for learning about climate and air quality. “I think it’s hard for children and anybody to understand the climate if they don’t understand weather. Where’s weather? It’s right outside your door.”

“The idea is to put scientific instruments outdoors around the school so that the students can extend their senses, so they can use that information so they can see the world around them in a much better way, a much more fulfilling way,” Johnson says.

Johnson points out that the award for Lots-To-Learn highlighted the impact that these projects can make for a relatively low cost. “What was really interesting was we got $75k to do it. The other winner was greening the top of the PECO building. They spent $9 million.”

Interpret Green has continued to work with the school district on additional schoolyards incorporating monitoring equipment and nature learning spaces. Johnson’s goal is to enable students to connect with and learn from nature, even when they can’t take a trip to a formal nature center. “I’m hoping to reimagine whatever potential there is to connect children and their classroom to the living world so that the school grounds become the nature center,” he says.

FEBRUARY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 13

I think it’s hard for children and anybody to understand the climate if they don’t understand weather.”

craig johnson, chief habiteer at Interpret Green

Opposite page: Designer Craig Johnson and educator Stephanie Kearney get help from students to mount a weather station in their schoolyard. Left: The weather station collects real-time data of outdoor conditions, which are available for classroom learning.

Schoolyards can also give students the chance to expand on what they learn when they do visit nature centers.

Since the 1970s, Montgomery County school groups have been visiting the Riverbend Environmental Education Center in Gladwyne, set on the hillside above the Schuylkill River (and I-76). All fourth-graders in the Norristown Area School District visit the center, totalling about 900 students from 43 classes each year, according to Julia Boyer, Riverbend’s education coordinator.

Before the field trips, Riverbend staff visited the classes to talk about what the students would see at the center and to tie the visit into their classroom learning. “The first visit into the classroom is to get them familiar with us. We talk about the concept of ecosystems and talk about food chains … get them ready for going out for three hours,” Boyer says.

“I make sure we’re hitting life sciences, biodiversity before their pre-lesson,” says Lindsay Armour, a fourth-grade teacher at Norristown’s Cole Manor Elementary School. After the pandemic forced a pause in the live visits, Riverbend’s educators rethought the program and came up with a different site closer to the schools. They chose the Norristown Farm Park, 690 acres with eight miles of trails, including forest, stream and pond habitats. According to Boyer, the park has one educator — not enough to cover every fourth-grader in Norristown. “So we got to be the educators in their lovely space,” Boyer says.

Boyer noted an unexpected benefit of exploring nature right next to the students’ hometown, a working-class, majorityBlack-and-Brown community, rather than in Gladwyne, one of the wealthiest suburbs in the nation. “At Riverbend [the students] say, ‘Those are big houses,’ and I say, ‘Yep, those are big houses,’” Boyer says. “They get the concept that nature is something over there. It feels like you have to drive here very far on a bus. We always said, ‘You’re welcome to come back,’ but rarely saw kids come back. This is not their neighborhood.” The farm park, on the other hand, is an easier place for the students to visit later and tie into their own neighborhoods.

As they have in past years, Riverbend educators return to the schools for a post-visit lesson, but since the pandemic they have shifted from learning in the classroom to spending time outside on the school

grounds. “Before the pandemic, we stayed indoors and did classroom-based activities.” Now, though, “we take the students outside to explore the ‘ecosystem’ of their schoolyard,” Boyer says. “How is the school an ecosystem? We find living and nonliving things. You can really see it clicking. They say, ‘Oh, we saw it there.’”

After Riverbend’s post-visit session, teachers continue with the same concepts. “Beyond that there are things I’ll do with a microscope,” Armour says as an example. “We might take a closer look at what’s around us, a nonliving thing like dirt, what does it really look like?” Armour also pointed out that outdoor, hands-on learning is ac-

cessible to children regardless of how well they are doing in other subjects. A student who has trouble with written materials in the classroom is at no disadvantage when it comes to watching birds or observing soil microbes under a microscope.

School grounds can also be a place for children to learn about and connect with the systems around them while they’re at recess. “Nature play takes the ecological piece without bashing kids over the head with it,” says Schuh.

“Kids use their imagination to guide the play.” On a standard playground the equipment (slides, swings, etc.) determines how kids play. “But to me the thing about

14 GRIDPHILLY.COM FEBRUARY 2023

PHOTOGRAPHY BY CHRIS BAKER EVENS

Penn Alexander teacher

Stephanie Kearney received a grant from Toshiba America to install this weather station in the schoolyard.

playing in nature is there are no rules, no handbook, just all the incredible resources. Seeds, leaves, twigs, whatever you can make and find becomes your play, and that is how it becomes so magical for kids.”

At McMichael Park, at Midvale and Henry avenues in East Falls, Schuh’s firm designed what she calls a hybrid between a playground and a nature play space. When a couple of trees had to be taken down, they cut the trunks into sections and incorporated them into the play area, for example set vertically in a row for children to cross, stepping from one to the next.

In Philadelphia, the Exploring Our Urban Watershed program run by the Fairmount Water Works has trained teachers of fourth-grade through high school students to teach students about how their schools and neighborhoods figure into water systems. These include local ecological themes as well as the human-built drinking water, sewage and stormwater systems. The program was inspired by schoolyard projects designed to reduce stormwater runoff, as the Water Works’ Ellen Schultz told Grid for a 2020 article on the program. “You’re doing projects on the grounds, but what about these students and teachers who use these grounds every day?” Schultz said.

Now, with funding from local pharmaceutical company Spark Therapeutics, Johnson, Schultz and partners such as the Philadelphia Water Department are working with the School District of Philadelphia’s GreenFutures sustainability office to scale up the use of schoolyards as science learning spaces and research stations.

Kearney, as well as Add B. Anderson School’s Kristin Nakaishi, who took part in

the Exploring Our Urban Watershed training program, are working with a planning committee to come up with the right combination of equipment and curriculum that a five-school network in West Philadelphia will test out.

The project will build on the experience of Exploring Our Urban Watershed as well as projects, including Johnson’s, that incorporated climate and air quality monitoring equipment. “So we’ve been tossing around an idea for a while,” says Megan Garner, the district’s sustainability manager. “By the end of the third year, I believe that we’ll have a model that we’ll be able to start bringing to other areas of the city, because ideally we’d like to be able to compare the Northeast to the Southwest and the Northwest to the Southeast. We want to make it accessible to all the students.”

Garner, Schultz and Johnson all emphasized the importance of using reliable equipment that will yield data that will not only be useful in the classroom but that external researchers and advocates can use.

At district-wide scale, such a network could provide powerful information about the Philadelphia environment. “If you were to imagine we had 200 nodes and we could

measure real-time heat index and measure real-time weather, have sensors in the ground, stormwater sensors,” Johnson says, “you could create a map, and show it all in real time.”

Reinventing the outside of schools also has the potential to change the relationship of students with their world.

“How schools imagine and perceive their schoolyards is a reflection of how they see their relationship with nature,” Johnson says. A brick and concrete school building surrounded by asphalt and a mowed lawn serves to seal children away from the outside world. “The industrial model is where we go to school and we give you learning, we train you. In that industrial model, a fundamental belief is the right to dominance of nature by humans, and that nature is here to serve us, and there’s no problem with neglecting it and there’s no problem with erasing it.”

The right kind of schoolyard, however, offers children the chance to explore their world and develop a sense of wonder, Johnson says, “to have a direct corporeal experience with your own senses of seeing the complexity of the world for yourself and know it is real. That’s the opportunity of a schoolyard.” ◆

FEBRUARY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 15

You have some fundamental learning that needs to happen about the ecological world.”

— sara pevaroff, principal of SALT Design Studio

LEARNING ENVIRONMENT

Philly establishes optional climate change curriculum, but lags behind neighboring New Jersey

In his classroom at Lankenau High School, veteran teacher Matthew VanKouwenberg points out to his students the connection between average daily temperatures across Philadelephia and tree canopies, noting that the lack of tree cover can leave some neighborhoods — often poor, often majority-minority — overheated in summer. VanKouwenberg, who teaches chemistry and environmental science at the 350-student magnet school in Northwest Philadelphia, takes it a step further, telling students that these discrepancies might make them and their relatives more susceptible to heat exhaustion or getting sick, or force them to pay higher costs to keep their homes livable. He teaches them how historical practices like redlining have contributed to environmental injustice. And then he asks them how they can help change it.

“It ignites this righteous anger,” VanKouwenberg says. “They should be mad about it.”

Rather than simply teaching students about climate change, climate injustice and

story by ben seal

photography by chris baker evens

the forces shaping their future, VanKouwenberg and some of his colleagues across the school district are attempting to motivate young Philadelphians to be agents of change. If anyone is going to address these colliding ecological and environmental crises, they are.

“You don’t have to passively accept what’s been given to you,” he says. “Don’t wait around until you feel like you have the power. Let’s empower you to take control of it.”

The climate change and sustainability curriculum is still in its infancy in Philadelphia public schools.

The seeds for the curriculum were sown in 2014, when the School District of Philadelphia’s environmental director, Francine Locke, returned from a conference on sus-

tainability and asked for permission to develop a full-fledged sustainability program. Alongside Megan Garner, the district’s sustainability manager, she looked at what large school districts around the country were doing. Some had programs in place to limit energy consumption or waste, but few had a demonstrated plan to educate students about sustainability and climate change.

“As a school district, we have a responsibility to not just make operational changes, but also in a very meaningful way incorporate sustainability into the curriculum,” Garner says.

For inspiration, Garner and Locke, who is now the chief sustainability officer for Delaware County, turned to Greenworks, the City’s long-term sustainability framework,

16 GRIDPHILLY.COM FEBRUARY 2023

for ideas about educational programming and community engagement. They also looked to the National Wildlife Federation, whose Ranger Rick character was a staple in childhood environmental education for Garner and many others, and adopted portions of its Eco-Schools USA program for hands-on learning about the environment.

In the Cloud Institute for Sustainability Education they found the third important element of what would become the school district’s approach to climate change and environmental education: the education for sustainability curriculum, which works with teachers to help inspire students to create change.

“It’s about education for a sustainable future and for sustainable development,”

Garner says. “It’s more for sustainability than about sustainability.”

That emphasis is important. The district’s goal was to develop a curriculum that teaches students the analytical skills,

including critical thinking and what Garner calls “systems thinking,” that will give them the power to seek solutions to the environmental and sustainability challenges that will shape their futures.

“We don’t want anybody to feel hopeless,” Garner says. “We want people to feel hopeful and start thinking about solutions. What are our barriers and how do we overcome those barriers?”

In collaboration with Fairmount Water Works and Ellen Schultz, its associate director for education, the school district has begun giving teachers the tools they need to deliver a curriculum called Understanding the Urban Watershed. Nearly a decade in the making, the curriculum teaches students from fourth grade through high school about

FEBRUARY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 17

Right now, as far as ecology is concerned, Philadelphia needs our youth.”

jessica naugle mcatamney, principal of Lankenau High School

Lankenau High School principal Jessica Naugle McAtamney (center) and teacher Matthew VanKouwenberg take their students out of the classroom to learn about nature and sustainability.

the city’s water systems — from stormwater management to drinking water and everything in between — and what they can do to be stewards for the watershed and advocates for climate change action. Schultz says this year’s effort will reach about 40 educators across 22 district schools.

Garner is also leading monthly climaterelated professional development sessions for teachers, exploring issues such as climate justice and the role that trees play in shaping the city’s environment. At a recent session, green schoolyards took center stage, tying into the school district’s upcoming launch of a greenscapes guide to help schools navigate the sustainability process. Over the past five years, roughly 400 teachers have participated in at least one such session, Garner says.

But while climate change education is a requirement for students across all grade levels and subjects in neighboring New Jersey, these trainings for Philadelphia’s teachers aren’t mandatory. As thoughtful as the curriculum may be, if it doesn’t reach every teacher it can’t reach every student. With the impact of climate change on students’ lives only bound to grow in the coming years — from severe weather to a sharper focus on sustainability and booming opportunities for a green workforce — the school district has ample opportunity to dive deeper, further connecting the city’s youth to the changing world around them.

“The commitment to every child learning about this is key,” Schultz says. “I don’t know that that will happen, but it should.”

Beyond the Four Walls

Jerome Shabazz, executive director of Overbrook Environmental Education Center (OEEC), has been working for two decades to give young people the tools they need to navigate their own green education, and he’s found several strategies to help kids learn.

“The learning environment is not limited to the four walls of your classroom,” Shabazz says. “In order for you to see it as a real issue, you have to see it not just in the sterile, synthesized environment of the classroom.”

At the OEEC, which Shabazz says began its work embedded in the environmental sciences and service learning communities at nearby Overbrook High School, every part of the environment at school and outside of it can be part of the learning expe-

jerome shabazz, executive director of Overbrook Environmental Education Center

rience. He stresses the “co-production of knowledge” as a critical piece of teaching environmental and climate science, making students an active part of their own education. At OEEC, climate change education incorporates conversations on engineering, geography, public policy and health care, drawing connections between the impacts of climate change and the personal experiences of students.

“This isn’t just science that some stranger wants you to know about in the future,” Shabazz says. “What implication does this have in your life?”

A conversation at OEEC about unusual

weather might lead to a review of the data, giving students a chance to validate their own experiences by looking at rising average temperatures or an increase in heat waves in their communities. As Shabazz says, “you can’t change what you don’t measure,” so he places emphasis on helping students identify the strategic indicators of climate change before opening up a dialogue about their implications. Ask students if their family members have asthma, heart disease or hypertension, and hands shoot up into the air, creating a window to connect those health concerns to poor air quality or dangerous temperatures in their neighborhoods.

18 GRIDPHILLY.COM FEBRUARY 2023

We help students understand how they can use their education as a tool for social reform, and how they can create a better life for themselves.”

Key to the conversation is a solutionoriented mindset, helping students see how planting more trees or improving urban infrastructure might offer a better path forward.

“We help students understand how they can use their education as a tool for social reform, and how they can create a better life for themselves,” Shabazz says.

When he looks at the school district’s approach to teaching students in these same areas, Shabazz says there’s “a great deal more” that could be done with career technical education (CTE). In his mind, CTE programs offer a better foundation to connect students to climate change and environmental issues.

“Over the last 30 to 40 years we’ve seen a reduction in emphasis on career technical education. I think that’s a lost opportunity,” Shabazz says, lamenting the closure of schools like Bok Technical High School. “That’s where we need to build the climate workforce.”

An Eye on the Stakes

Lankenau High School may not be focused entirely on CTE, but it does offer a window into what an education grounded in the environment can look like within the school district. Every teacher is asked to build ecology and environmental science into their lessons and use the school’s Upper Roxborough campus as a classroom. The art teacher takes students outside to draw, the special education classes plant greenery, the social studies teacher is engaged in beekeeping.

Principal Jessica Naugle McAtamney, now in her second year at Lankenau, says that the city and science standards are both changing, and she wants the school to be part of the shifting approach to education.

“Right now, as far as ecology is concerned, Philadelphia needs our youth,” McAtamney says. “Who’s working with them to ensure that they understand what the stakes are?”

VanKouwenberg is among the educators demonstrating those stakes. After a recent trip to Morris Arboretum, he talked with students about the American chestnut tree, which is all but extinct, and how cross-breeding it with the Chinese chestnut has allowed restorationists to help preserve trees that are up to 94% American chestnut. The same methods will be important to save plants from rising temperatures or changing water conditions in the future, VanKouwenberg says.

A project with the Philadelphia Water Department has given students the chance to propagate mussels like those used to help clean the water of the Schuylkill River. As they’ve watched the mussels grow from the size of a pencil point to three centimeters, the students have debated the best way to manipulate their growth, either by altering their food source or changing the temperature of their water, in order to maximize their beneficial impact.

“They’re using higher-order thinking skills to design experiments themselves, all with the underlying idea of sustainability and how climate velocity will change,” VanKouwenberg says.

McAtamney is a strong believer in conservation through appreciation. That way of thinking underscores a Lankenau education, where students are taught to understand the environment and the challenges

it faces so they can work toward solutions.

“Being here on this campus provides that opportunity,” McAtamney says. “We have a lot of work to do in order for the district to understand why this is a unique gem.”

Tangible Connections

Elsewhere in the district, as the curriculum is being dispersed, schools are improving on their greenspaces and using them to deliver some of the hands-on education that Overbrook and Lankenau model. EmmaLynn Melvin, the green infrastructure program manager for the district, says 42 of its schools now have green stormwater infrastructure, and about 10 new systems will be built this year. Each of them gives students a chance to steward the places where they learn and play, as well as a window into the many ways that sustainability can improve their lives.

The school district has a goal to reach 30% tree canopy on all of its campuses, and the effort to do so ties back directly to the curriculum in the classroom. Melvin describes the greening process and the maintenance it requires as a hands-on part of “a meaningful watershed experience.”

Asphalt schoolyards, where temperatures rise higher without adequate shade, are a microcosm of the challenges of climate change, Melvin says. By planting trees and tending to them over time, students can learn about the benefits of a healthy canopy.

“They’re able to see how the transformation affects the schoolyard and the community,” Melvin says.

Across the district, establishing these tangible connections is just as integral to climate change education as delivering the facts. And once the connections are made, educators are working to help students learn to improve their surroundings.

“Part of my effort is to get kids to be aware that they are part of the solution and also part of the problem,” Melvin says.

Climate change education is “training for life,” Garner says, in that it can connect students to the world around them in meaningful ways.

“We want the graduates from the district to be engaged members of their community and contribute to where they live,” Garner says. “We want them to feel empowered and know that they have a voice and what their options are.”

◆

FEBRUARY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 19

Jerome Shabazz, of the Overbrook Environmental Education Center, believes career technical education would prepare students for the green economy.

KEYNOTE JESSICA HERNANDEZ Indigenous environmental scientist • Author of Fresh Banana Leaves FEATURED SPEAKERS INCLUDE: Sandor Katz, Wild Fermentation • Owen Taylor, Truelove Seeds • Chris Bolden-Newsome, Truelove Seeds & Sankofa Community Farm • William Padilla-Brown, MycoSymbiotics • ...and many more! SESSIONS INCLUDE: A More Just Food System Through Cooperatives • How Food Hubs Can Support Producers & Local Food Ecosystems • Starting a Farm: From Your Vision to Your Business Plan • How to Advocate for a Just & ClimateFriendly Food System in the 2023 Farm Bill • How Can We Protect the Meaning of Organic? • Permaculture Roundtable • Regionalizing Flax for Linen: From Seed to Cloth • Ag-Adjacent Career Panel: Finding Your Passion Outside of Production Farming • ...and many more! LEARN MORE & REGISTER PASAFARMING.ORG/CONFERENCE 90 sessions Mixers & meet-ups Trade show Kids program

FEBRUARY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 21 www gtms org info@gtms org American Montessori Society Accredited School Day and All Day Montessori Toddler, Pre-K and Kindergarten Arch Street, Center City, Philadelphia learning without limits Join the Preservation Alliance and Green Building United for a panel discussion on the C-PACE program, which offers financing for sustainability upgrades to existing properties. Financing for Historic Property Energy Upgrades Information & registration: preservationalliance.com/c-paceprogram Wed., Feb. 22 8:00-10am 123 S. Broad Street 5th Floor ... SummerSessions SummerSessions June 20 - August 18 Register online at friends-select.org/summer Make space in your home this New Year. Recycle your clothes AND electronics right from your doorstep with Retrievr. To schedule your pickup and learn what items we accept, head to retrievr.com/greater-philly

Advocates, City Council and the school district make drinking water safe for students

Dwayne Wharton was tasked with helping to solve one health care crisis affecting kids when he discovered another.

Wharton was working for The Food Trust in the mid-2010s, and that organization’s goal was to reduce the number of sugary beverages, especially soda, kids were drinking. They encouraged students to drink more water from the ubiquitous water fountains. But many kids, Wharton learned, were reluctant to drink from the fountains.

“We spent enough time in schools to know about the old water fountains,” Wharton says. Students told him that some were used as trash receptacles, and some fountains were turned off and had “do not drink” signs on them. “Kids were

22 GRIDPHILLY.COM FEBRUARY 2023

story by bernard brown • photography by chris baker evens

While

As The Food Trust was raising students’ concerns about water quality in schools, Philly environmental leaders and politicians were sounding alarms about another reason to dodge the school tap water: it could be contaminated with lead.

“I think the way this started goes way back to Flint,” says David Masur, executive director of PennEnvironment. In 2013 Michigan state officials overseeing cost-cutting measures for Flint’s city government switched to a new, cheaper water source without considering that the new source would be slightly more corrosive, dissolving lead out of the city’s old pipes and thus poisoning the water supply for the city’s residents, more than half of whom are Black and more than a third of whom live below the federal poverty line. “I think Flint … called into question something we took for granted for a really long time: that when we turn on the tap that water is safe,” Masur says. Thanks to the crisis in Flint, it dawned on Philadelphians “that lead in drinking water was still fairly common and it didn’t matter that much where you live, whether you were in a blue district or red district or purple district.”

The Problem with Lead

dwayne wharton, former Food Trust director and lead-free schools advocate saying, ‘If that water over there isn’t safe, why would this water be safe over here [at functioning fountains]?’ Kids were bringing this up.”

Compared to other public health threats, cutting back on sugar from sweetened drinks appears to be pretty simple: drink free tap water instead. That only works, though, if people trust the tap water, and it was clear that Philadelphia youth did not.

In some ways lead is an incredibly useful metal. It makes paint more opaque and water-resistant. In gasoline it stopped engines from knocking. It is dense, making it handy for fishing weights and bullets. It is soft, melts at a relatively low temperature and resists corrosion, making it a convenient material to form pipes, as the ancient Romans discovered. The Latin word for the metal, plumbum, gives us our words for water pipes (plumbing) and the people who fix them (plumbers).

The problem is that lead is a potent neurotoxin. High levels of lead have been wide-

ly recognized as toxic since the late 1800s, but in the 20th century it became clear that chronic exposure to low levels of lead is particularly harmful to children, causing developmental delays and behavioral health problems later in life. This realization led to efforts to get rid of lead where children could be exposed, including a national ban on lead paint in 1978 and a phase-out of leaded gasoline starting in the 1970s. These measures resulted in a steep decline in lead exposure, celebrated as a major public health victory.

Today most of the attention on lead focuses on exposure to flaking paint and contaminated dust that kids encounter in old houses and apartments, which is one reason that Flint’s lead crisis came as a wakeup call. Philadelphia has a lot of similarities to Flint, including an old water system built when lead was widely used in plumbing.

“Right before I came into office the tragedy of Flint, Michigan, had just come to light, when an entire town had been poisoned through a change in the water by the government,” says Helen Gym, a current mayoral candidate who served on City Council from 2016 to 2022. “I made a vow back then that we wouldn’t become Flint. In an aging city like ours we had to take positive, proactive action on this.”

Gym, who by the time she ran for City Council had been a longstanding advocate for public school students, held a series of education town halls. At Sayre High School in West Philadelphia, students talked about the water fountains. “This group of students wanted to talk about what it was like to go to school and have water fountains shut off or fountains that did exist put out murky water.”

“We ended up doing a meeting in City Hall with a group of middle and high school students who addressed the School Reform Commission [the body that then oversaw

FEBRUARY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 23

Kids were saying, ‘If that water over there isn’t safe, why would this water be safe over here?”

working to reduce soda consumption at schools, Dwayne Wharton discovered students were reluctant to use water fountains.

Philly public schools],” Gym says. “When you look into the eyes of a 10-year-old who nervously wrote out her comments and asked leaders to fix the water in her school, you can’t look away from that.”

In June 2016 Gym introduced a bill to City Council mandating that schools test water from fountains for lead and to shut off any that had levels higher than 10 parts per billion, at the time the strictest standard in the country.

T he school district itself kicked off a drive in August 2016 to install three hydration stations (filtered water fountains that also filled bottles) in each of its 218 schools within the year. “The school district immediately became a partner on the hydration stations,” Gym says.

Parents of school district students didn’t want to wait while their children drank tainted water. They also began advocating for improvements. At the Henry C. Lea School (grades Pre-K through 8) in West Philadelphia, the home and school association (HSA) began raising money to buy hydration stations. “The process for putting in water stations was so slow and bureaucratic, I said as parents can’t we just buy a station, just one or two? Surely our building engineer could install them,” says Adam Weaver, a Lea parent and member of the HSA. “Some of it is you think about your own kid, but we’re in a privileged position. We can send our kid in with a big water bottle, but what about the wider school community?”

In the end the HSA raised enough money to pay for two hydration stations, but a principal transition slowed down efforts to install them. By the time the new principal had settled in, the district had installed three hydration stations, and the HSA shifted its focus to buying water bottles for students to bring to school and fill with the filtered water.

Philadelphia students learn in buildings that are, on average, 70 years old, according to Reggie McNeil, the school district’s chief operating officer. Sayre’s building dates back to 1949. About a mile away, the oldest section of the Lea School was built in 1914. School buildings like these and the city water system that feeds them have old pipes with lead soldering, McNeil says. It’s an “old piping system and old material. The lead is coming from that.”

The district, chronically scrambling for operating funds due to the city’s relatively

poor tax base (compared to wealthier districts such as neighboring Lower Merion) and underfunding from the state, has fallen behind on maintaining its old infrastructure. Decades’ worth of deferred maintenance has piled up. A 2017 report assessing the state of the district’s schools found that it would cost $4.5 billion to fix everything. Although removing lead from school pipes would, on the face of it, seem to fix the problem, McNeil says that that would entail ripping out entire plumbing systems,

helen

24 GRIDPHILLY.COM FEBRUARY 2023

LINETTE AND KYLE KIELINSKI

In an aging city like ours we had to take positive, proactive action on this.”

—

gym, former City Councilmember and current mayoral candidate

and there could still be lead coming from the city’s pipes that feed the schools. Filtering the water where students get it is, on the other hand, a simple fix. “This is one of the best ways we can do that, to give them a chance to drink clean, filtered, cool water right now,” McNeil says.

Thanks to the 2016 legislation, ultimately signed by Mayor Jim Kenney in the beginning of 2017, the district began posting the results of its water fountain tests. “Sunshine is the best disinfectant,” Masur says of the law’s requirement to share testing data. “We have to have that to make good decisions. The school district had done some testing but didn’t share it. Helen Gym’s law said they had to test all the outlets in a 60-month period and within 30 days post on the website, and where they found elevated levels of lead take the fountain offline and fix it.”

At Lea, the district ran its tests in February 2019, checking the eight hydration stations that had been installed by that point as well as one older water fountain and three sinks in the nurse’s office and lunchroom. All came in under the 10-parts-per-billion threshold. The hydration stations reduced lead to undetectable levels, and the older water fountain also had undetectable levels though the sink faucets had levels of 1.4, 1.5 and 5.4 parts per billion.

Although 10 parts per billion was the threshold for shutting off a drinking water

outlet, advocates argued that, as the World Health Organization points out, there is no safe amount of lead. In early 2022 PennEnvironment and the Pennsylvania Public Interest Research Group analyzed the district’s published numbers and issued a report criticizing the district’s results as well as its slow testing pace.

According to the report, as of February 1, 2022, the district had tested 29% of its schools and 61% of the fountains and sinks tested had detectable lead levels. The report also argued that the district’s testing methods could be understating the actual lead levels in real-world use of the fountains. The report pointed out that there is no safe level for lead; even low levels of lead can lead to cognitive deficits and behavioral problems later in life. It would be safest to replace all older faucets with filtered hydration stations.

In March 2022 Gym introduced legislation that would require the school district to do just that. “We wanted to accelerate things,” she says. “Like anything within a big system, things slow down … In 2016–17 we passed back then what was the nation’s best standard at 10 parts per billion, but we shouldn’t tolerate any level if we know the filtration systems can reduce levels to effectively zero.” She says lead poisoning in schools was a problem they knew they could knock out quickly. “I don’t want to be

talking about lead poisoning in schools in 10 years.” Mayor Kenney signed the legislation into law at the end of August.

In October the district announced that it had won a grant for $5 million from the EPA to pay for the last of the hydration stations: 755 on top of the more than 1,500 it had already installed.

According to the district, the hydration stations are simple to maintain. “Building engineers are qualified to remove and replace filters,” says Stephen Link, director of the district’s environmental office. “It takes five minutes.”

“We are excited about the changes we are a part of to remove lead in water,” McNeil says. “Our passion is that we want to provide a safe space for our kids and for our staff.”

Link points out that the hydration stations promote the use of reusable water bottles, reducing plastic waste from bottled water.

For the environmental advocacy community, the key lesson is that, in the end, it is best to skip testing and simply install filtered water outlets. “What we realized is lead is so pervasive, you’d have to test every outlet every year,” Masur says. “Actually it’s just cheaper to replace them all.”

Gym draws a broader message about setting goals for the city even when the resources to achieve them aren’t apparent. “When we are clear about our missions, we can go out and leverage resources to make it happen. We often don’t take on additional infrastructure projects because capacity isn’t there. That can’t be solely the reason we do or don’t do a thing,” Gym says. Once the City decided to prioritize getting lead out of school drinking water, it was able to find the money. “That’s the lesson of the grant … It’s not just about how much money exists. It’s about how well we do in exciting and catalyzing investments when this modernization effort we’re doing transforms the lives of young people.” ◆

FEBRUARY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 25

Opposite page: Former City Councilmember and current mayoral candidate Helen Gym proposed a bill in 2016 to test schools’ water supplies for lead. Left: Hydration stations not only provide much safer water but also greatly reduce single-use plastic bottles.

BLOOD GRIP

26 GRIDPHILLY.COM FEBRUARY 2023 ILLUSTRATION BY ABAYOMI LOUARD-MOORE

fiction

an excerpt from a forthcoming novel by constance garcia-barrio

PART ONE

Virginia, June 1837 1

Alsie Stone’s breasts leaked milk from the moment of her escape. Over hard miles, her milk painted stripes of terror down the front of her heavy tow-cloth blouse. The stitch in her side grew teeth. She tripped in the darkness, fell on her face, and jounced the baby in the sling on her back.

Footsteps ahead of her stopped. “You all right?”

Alsie raised her head and spat, but the sharp-sweet taste of dirt and rotting leaves still prickled her tongue.

The baby cried.

“Hush, Hannah!” she said.

Alsie sat up, uncorked a small bottle. Her heart skittered as she gave Hannah more herb-water to make her sleep. The less she used, the better. She scrambled to her feet, then limped toward her family.

“Ben,” she grabbed her husband’s arm, hard as the iron he worked at his forge, “got to stop.”

“Can’t be long.” He handed her a cow bladder full of water, his face grim. She looked into his eyes, starved for reassurance, but he turned away. “Miller might be huntin us already,” he said.

Alsie’s stomach lurched when she heard Miller’s name. The devil alone knew what Bellaire’s overseer would do if he caught any of them, especially her. He’d first threatened her soon after he arrived at the plantation a year back: Go to his cabin or he would find cause to whip her sons.

After leaving his bed that time she had raced to the creek, stripped, and bathed until the chill water set her teeth chattering. She recalled the cabin’s mustiness, the grimy sheets against her skin, Miller’s smell of horse flesh. His finger had kept circling her nipple, and the pleasure it had given her deepened her shame. Her getting with child and lying to her mistress, saying that she

was spotting, put a stop to his bedding her, but by then Ben knew about Miller. Everyone did.

She’d tried to use her beauty to shield her sons, but Ben wouldn’t allow it. She’d been his alone too long. Master had given her to Ben about a year after her first blood, to ensure good work from him. She was afraid of Ben at first because he was big, rough-spoken, and nine years older than she was, but he’d taken good care of her the few times she got sick. In eighteen years, love—thorny sometimes because they both could be cross-grained—had grown between them.

“I’ma wait till you’re two months out of childbed,” he’d said, “then I’m runnin with the boys and the baby, if it’s mine. Crazy for you, Alsie,” he’d gripped her arms so hard that she’d gasped, “sorely hope you’ll come, but I got to leave or break Miller’s neck.”

Her neck cramped when she remembered Ben’s words, but he wouldn’t have said them if he’d stopped caring for her. She raised the bladder and drank more water.

“Merciful Father,” she said when she finished, “help us!”

She felt for the pouch at her waist that Yowande, the African woman who’d reared her, had prepared. Yowande had said nothing when Alsie confided that she would flee, but the old woman’s eyes had darkened so. Yowande had prayed over the pouch for days. It held chalk, brown soap, candle stubs, lucifers to light them, herbs, and a tiny doll much blessed by Yowande. Coins earned from selling produce from Alsie’s garden plot added little weight.

Alsie closed her eyes and recalled Yowande’s face, wrinkled and dark as a fig, tribal marks high on her cheeks, the whites of her eyes aged to the color of parchment. Remembrance of that time-writ visage sent warmth rippling through Alsie, but unease

she’d felt since Hannah’s birth crawled in her stomach.

A fox barked, the wind rose, and the whipping branches made her think of spirits trapped in the trees. Something brushed her arm and she jumped. Jake, seventeen, her oldest son, had put his broad hand on her shoulder. His bundle, stuffed with blankets, vittles, a knife and an axe, lay at his feet. She passed him the waterskin.

Jake gulped so loud that she counted his swallows before he passed the cow bladder to Jerusalem, just turned sixteen. Jerusalem swigged water, then returned the bladder to Ben, who put it back in the leather sack fashioned from his thick smithing apron. While he and Jerusalem checked their stolen guns, Alsie gave thanks that master had trusted Ben to repair them, so he knew how they worked.

Jake made a steady worry-grunt, a gutdeep growl he’d kept up since they’d left Bellaire. He didn’t talk, but he made his feelings known.

“Come on!” Ben waved.

Jake got going.

Alsie’s knee throbbed but be damned if she would give Jerusalem call to say, “House niggers got no grit.” He thought her life easy because she worked indoors. Housework had spared her so that she looked barely in her twenties, but she lived under mistress’s heel. Mistress could be kind one minute, full of vigor, trying to do five things at once. Then again, she fell into moods so crabbed and sour that she dumped slop jars on Alsie’s head.

“Alsie!” Ben, up ahead, motioned for her to hurry.

She plunged a hand into her pouch, and her fingers closed on the doll. Eyes brimming, knee aching, she squeezed it. “Keep me goin,” she said.

They trudged for miles over ground sown with stones and balls from sweet gum trees that crunched and stuck to her shoes. The sky held a hint of light when Ben called a halt. She followed his gaze to a small house of white clapboards backed up against a hillock. Cornstalks spread on one side of it, and a barn, smokehouse, henhouse and pigpen stood on the other. A log outhouse was at a distance.

A cock crowed, and it seemed less a sign of coming light than a threat of deeper darkness. When Ben signaled to them, they drew back into the bushes. He scout-

FEBRUARY 2023 GRIDPHILLY.COM 27

ed the woods and fields for what seemed a lifetime, then crept to the house and tapped on a window. What if he’d made a mistake? Alsie tightened her bottom because she was trickling down her leg.

A young black man cracked open the door and wiped his face with a red handkerchief, the safe sign the itinerant preacher who’d visited Bellaire told them to expect. Someone inside pulled shut the homespun curtains. After Ben waved them forward, Alsie staggered over the threshold.

Inside, Ben extended his hand toward the man. “My name is—”

“No names, brother,” the man said. “Somebody come askin, we can say we don’t know you.”

“Good sense, but a sorry thing.”

The smell of wood smoke eased the hammering in Alsie’s temples. The brick hearth was newly swept, a twig broom leaning against a wall. The brown-skinned farmwife’s apron couldn’t hide that she was weeks from giving birth, and her cheeks seemed to glow as she roused the fire’s embers to flame. A half-finished cradle stood in one corner and a spinning wheel in another. Mint, basil and comfrey hanging from ceiling beams rustled and scented the room. The benches beside the plank table had a piney smell and felt new and splintery but had room for both families.

Before Ben ate, he looked at Jake, Jerusalem, Hannah and Alsie, his lips moving. Praying? He didn’t much like the secret prayer meetings in the woods, but now he whispered “Amen.” His handsome face, dark brown with a red tinge, had changed little over the years, but time had stolen his ease of manner, his laughter. She recalled how he used to buck dance like a wild man and ached with regret.

They gazed at each other across the table, and the warmth in Ben’s eyes let her dare hope that they would reach Philadelphia.