■ The EPA says lead pipes must go p. 8

■ Are monarch butterflies really in crisis? p. 20

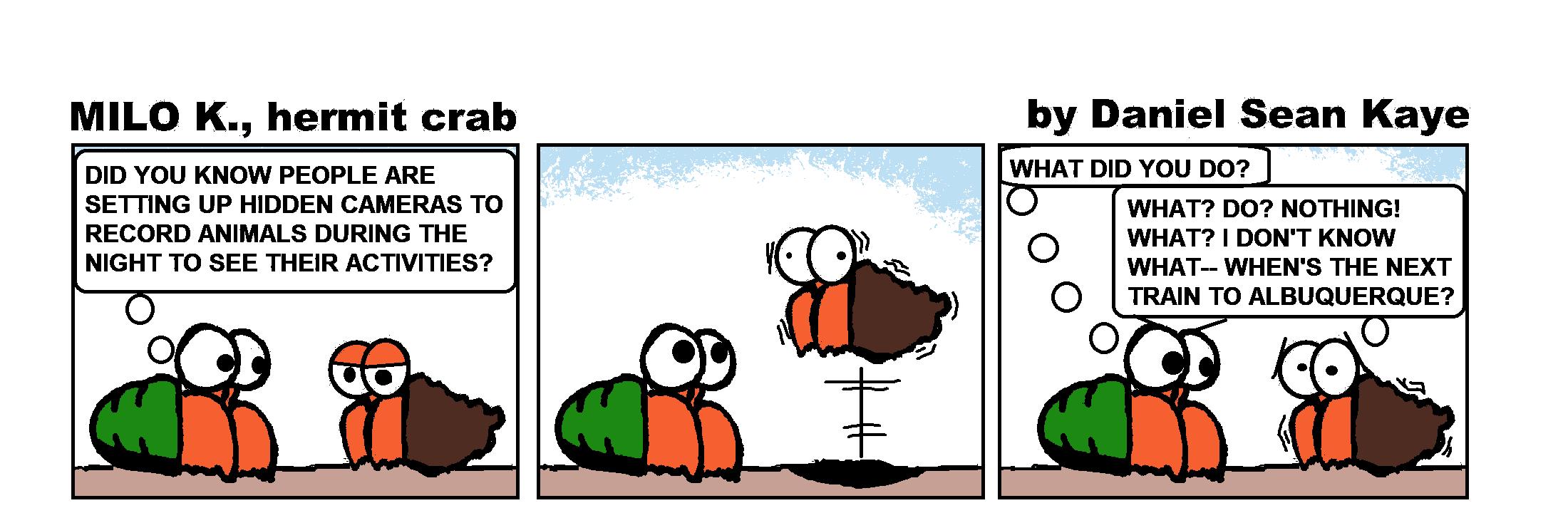

■ Nocturnal animals caught on camera! p. 28

■ The EPA says lead pipes must go p. 8

■ Are monarch butterflies really in crisis? p. 20

■ Nocturnal animals caught on camera! p. 28

Philly Truce Foundation aims to stem rampant gun violence one block at a time

Mazzie Casher, co-founderA

NextFab is a network of membershipbased makerspaces, providing shared workshops and education in the areas of woodworking, metalworking, laser cutting, 3D printing, textiles, jewelry making, and digital manufacturing tools.

NextFab is a network of membershipbased makerspaces, providing shared workshops and education in the areas of woodworking, metalworking, laser cutting, 3D printing, textiles, jewelry making, and digital manufacturing tools.

+ Maker Series: MIG Welding: Design and Weld a Smokeless Firepit

+ Maker Series: MIG Welding: Design and Weld a Smokeless Firepit

+ Maker Series: CNC for Woodworking: Machine a Custom Wooden 3D Gameboard

+ Maker Series: CNC for Woodworking: Machine a Custom Wooden 3D Gameboard

+ Maker Series: Custom Jewelry: Silversmithing Stacking Rings with Stone Settings

+ Maker Series: Custom Jewelry: Silversmithing Stacking Rings with Stone Settings

Mother’s Day Workshops

Mother’s Day Workshops

+ Design and Make Your Own Textured Jewelry Workshop

+ Design and Make Your Own Textured Jewelry Workshop

+ Make Your Own Leather Coasters Workshop

+ Make Your Own Leather Coasters Workshop

Buy One, Get One Half Off for Mother’s Day!

Buy One, Get One Half Off for Mother’s Day!

NextFab’s Maker Series is a two-month program that gains you 2 months of membership, up to 5 classes, unlimited shop access, and a cohort to learn alongside.

NextFab’s Maker Series is a two-month program that gains you 2 months of membership, up to 5 classes, unlimited shop access, and a cohort to learn alongside.

Sign up at nextfab.com!

Sign up at nextfab.com!

publisher

Alex Mulcahy

managing editor

Bernard Brown

associate editor

& distribution

Timothy Mulcahy tim@gridphilly.com

deputy editor

Katherine Rapin

art director

Michael Wohlberg writers

Bernard Brown

Jessie Buckner

Constance Garcia-Barrio

Gregg E. Gorton

Zane Irwin

Dawn Kane

Emily Kovach

Jordan Teicher

photographers

Chris Baker Evens

Matthew Bender

Troy Bynum

Jordan Teicher

illustrator

Bryan Satalino

published by

Red Flag Media 1032 Arch Street, 3rd Floor Philadelphia, PA 19107 215.625.9850

GRIDPHILLY.COM

If you want to elicit some angry comments from readers, print something unflattering about cats. We’ve done that more than once in Grid, pointing out the devastating impact that outdoor cats have on wildlife (they kill billions of birds, mammals and other crititers per year in the United States). Author Scott Weidensaul drives that point home again in our interview about migratory birds and how we can help them — but he doesn’t stop there. He adds the important point that if we want a greenspace to be good bird habitat, we need to think about limiting dogs, even leashed ones. Now we’ll have the dog people after us, too.

Why stop there? While we’re talking about the environmental impact of pets, we need to think about what they eat. Every carnivorous pet we maintain requires an enormous pile of dead animals (fish, chickens, pigs, cattle) over the course of its lifetime. Cats (not to mention my former, admittedly niche, pet of choice, snakes) are obligate carnivores, meaning they have no choice but to eat animals. In addition to making me reassess the moral value of adopting strays — since any single carnivore rescue dooms other animals to be ground up to feed it — this realization made it even harder to ignore the mountain of resources beneath that pile of dead animals*.

It takes a lot of grain to feed the unfortunate livestock that become their food. That feed, in turn, requires a lot of land, water, fertilizer, diesel and pesticides One study from 2017 estimated that cats and dogs in the U.S. account for 25-30% of the country’s environmental impacts from animal production.

So is it time to put Fluffy and Fido down to save the planet? Although that would arguably result in fewer total animal deaths and a smaller environmental paw print than letting them live to a ripe old age, we can still accomplish a lot with a more moderate approach.

It is possible for dogs to consume a meatless diet, and if they don’t, dry pet food generally has a smaller paw print than wet. Some of the researchers looking into the environmental impact of pet food have suggested using insects, which are particularly efficient at converting feed to meat.

In our household, as the snakes aged out we shifted to adopting rats, pets that mostly eat plant matter and that are, in my experience, as least as loving and engaging as cats. Rabbits fit the same bill at a larger, more-huggable scale.

A human’s choice to eat a plant-based diet results in a smaller footprint of land, water, pesticides, fertilizers and emissions. Likewise, choosing to love a plant-eating pet can be the sustainable choice.

bernard brown , Managing Editor* A lot of what goes into pet food are animal byproducts that humans wouldn’t eat, but those by-products still have value in alternative uses, such as fertilizer and biofuel. Thus bidding up the price of by-products to include them in pet food raises the price of fish or livestock overall and incentivizes more animal production and killing.

A look at the life of devoted birder James Carroll, the first Black member of the Delaware Valley Ornithological Club

GRID is honoring Black Birders Week (May 26 - June 1) by printing an obituary recently published by the Delaware Valley Ornithological Club (DVOC) about their first Black member, James “Jim” Carroll.

On the 30th anniversary of the founding of the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge at Tinicum, June 30, 2002, pioneering Black birder Jim Carroll’s ashes were spread in the marsh impoundment at a ceremony attended by his widow Helen, two of their daughters and their husbands, grandchildren, deputy manager Gary Stolz, manager Dick Nugent and luminaries such as Congressman Curt Weldon. The attendees honored Jim as the refuge’s first caretaker. This unsung, unassuming gentleman who was soft-spoken and habitually chewed on a toothpick, was always eager to help others, and many were said to have relied on his wisdom, knowledge and friendship.

When Jim was born on April 9, 1922, the most southwestern area of the city was called The Meadows, but today it is the Eastwick neighborhood, which is a diverse (majority BIPOC) community abutting the Heinz

Refuge. It remains flood-prone just as it was when Jim was young. Doubtless, his later development into a fine naturalist had much to do with his having spent his formative years in The Meadows with ready access to the marshland. His granddaughter, Donna Rucker Roberts, told me: “He learned the love that he had for the outdoors there.”

After high school, Jim worked for two years, but when the U.S. declared war in 1941 he joined the Army, yet was lucky not to be deployed overseas. After his discharge, he and his wife, Helen Sherman Carroll, were able to find a house and start a family. Jim continued to visit the Tinicum Marsh as often as time would allow during the 1940s and early ’50s.

The work of local environmental groups to stop the destruction of the marsh resulted in the Gulf Oil Company donating 145 acres of marshland to the City of Philadelphia in 1955, then called the Tinicum Wildlife Pre-

serve. Jim was hired as the first warden and caretaker of the new preserve. He worked out of an office built for him on pilings next to the dike that separated Darby Creek from the body of water called the impoundment.

In 1958, Jim’s childhood home, along with most of the other homes in The Meadows, was razed to make way for a controversial “urban renewal.” A thriving community was destroyed. While most of the homes lacked city services for water and sewage, many of the 19,000 residents reportedly felt that those detriments were balanced by the essentially rural lifestyle they enjoyed within the city limits.

The Meadows was one of only a few integrated neighborhoods in the entire city, and Jim’s daughter, Martha Carroll Rucker, recalls: “There were never any issues of racial dissension.” It provided space for food and flower gardening and for keeping chickens, pigs and even cows, as well as access to nearby creeks for swimming, bathing and fishing.

Unfortunately, the nature of the community was not appreciated or valued by the Redevelopment Authority and the politicians who saw fit to designate the neigh-

borhood as “blighted” and the houses as “poorly maintained.” Tragically, and with utmost irony, they viewed it as a good spot for the relocation of Black families who were being displaced from their homes in North and West Philadelphia to make way for other “renewal” projects in those areas. Jim’s parents were forced to move.

At the Preserve Jim did his job so well and was so admired that he was awarded the key to the City of Philadelphia in 1963. His daughter Martha recalls how proud he was to don a suit (rather than his usual brown khaki uniform) for the ceremony.

In the late 1950s, Jim happened to meet two young Delaware Valley Ornithological Club (DVOC) members who were birding at the preserve: John C. “Johnny” Miller and Joe Devlin. They had joined DVOC in 1951 even though both were only 15 years old at the time. Despite his being nearly that same number of years older than they were, Jim and the younger men became fast birding buddies. We may imagine that Jim’s new friends were impressed with him not only because of his status at the preserve, but also his knowledge of the area and his general naturalist skills. Likely, they learned a good deal from one another.

On October 19, 1967, at the age of 45, Jim became the first Black person admitted to DVOC (more than 75 years after its founding), having been duly sponsored by the

then-required three members.

Sometimes Jim would travel with other DVOC members to a birding destination of particular interest, such as Pocomoke Swamp in Delaware. However, because of persisting Jim Crow segregation laws, Jim was not allowed to stay with the others in the whites-only motels, so he had to seek his own lodging. Local diners often presented the same barrier, so the group would have to make do with takeout or store-bought food.

Jim’s granddaughter Donna recalls going with him to the preserve very early a few mornings each week before school when she was only seven or eight years old. They would drive to the Scott Paper Company near the airport, park, and then take the “company” truck over to the preserve. They would drive or walk out to his office, observing birds and whatever else they might notice — she recalls his delight at finding a bird and telling her all about it. He also kept lists of the mammals, reptiles, amphibians and fish he spotted. DVOC member Dwight Molotsky described Jim’s sharp vision, which missed very little, as his “golden eyes.”

When Donna was 14, she asked her grandfather if she could work with him. He assented, but she was surprised and taken aback at having to work on a hot day clearing and chopping up brush for removal. She had thought she would be bird watching,

but laughingly said, “I learned you had to take care of the area.”

Tragedy struck more than once. In the 1960s, an arsonist torched Jim’s office, which DVOC member Nick Pulcinella recalls had been “a beautiful headquarters building [with plexiglass on three sides], and scopes and binoculars for the public to use, a library of bird books and a poster-sized, weekly bird checklist pinned to the wall.” After the arson incident, which was never solved, Jim worked out of a small wooden shed (or Quonset hut) a little farther out on the dike road. It had a small, coal-burning stove for heat but was only large enough for Jim and one or two other people. But then there was a second arson incident, so eventually a small, stone headquarters building was erected near the front entry road to the preserve. That building survives today, though it has not been open to the public since the beautiful, environmentally exemplary Cusano Environmental Education Center opened in January 2001.

The Tinicum Marsh Wildlife Preserve became the Tinicum National Environmental Center in 1972 under President Nixon. By that point, the preserve had grown to about 1,000 acres, as more adjacent land and marsh were preserved. Jim was the first non-managerial employee to be hired by its new federal overseer, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Though his initial assignment was as a maintenance man, he was eventually given the title of biological technician.

Initially, he worked under managers Ken Chitwood and then Scott Stenquist. Later, his boss was the long-tenured Nugent, who saw Jim through to his retirement in 1987.

James Carroll died unexpectedly in his sleep on May 19, 2001.

Twenty years after his ashes were spread at the refuge, family members and luminaries (including Mayor Jim Kenney) gathered again, this time under the aegis of manager Lamar Gore, who spiritedly announced that the venerable platform upon which Jim’s original office had been built would forever after be known as the James Carroll Observation Tower. A new plaque was affixed and there was no doubt whatsoever in Donna’s voice when she proclaimed of her grandfather’s love for the Tinicum Marsh: “His spirit will always be here!” ◆

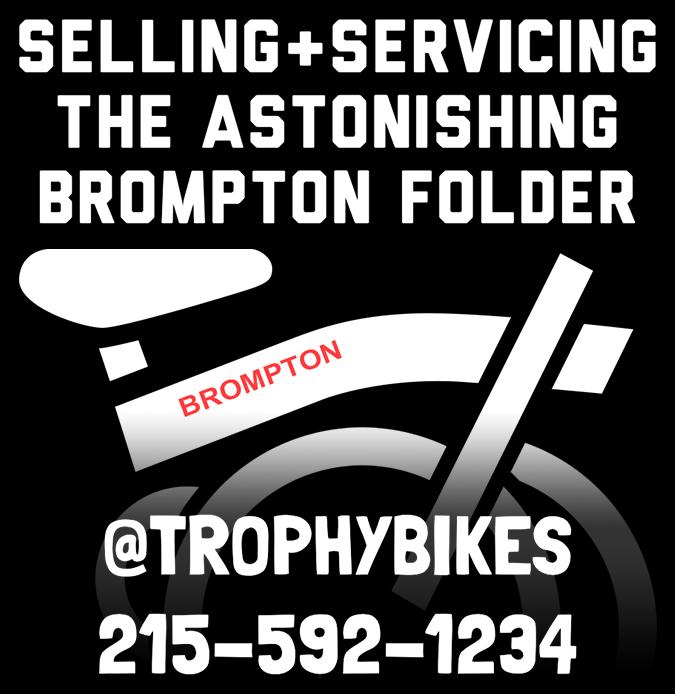

Operation Hug The Block holds nightly vigils on streets beset by violence by constance garcia-barrio

In the early hours of September 17, 2023, Mazzie Casher and Steven Pickens were foot patrolling near A Street and Indiana Avenue in Kensington, a hotspot for gun murders. The co-founders of the Philly Truce Foundantion, a nonprofit that tackles gun violence among the city’s Black youth, were accompanied by a Philadelphia police officer and other anti-violence activists. It was part of Operation Hug the Block, an initiative designed to show neighbors that they could become a presence that deters killings.

Around 1 a.m., while the group was on patrol, a masked man in a hoodie rode a bike up to their base where they rested between

patrols. “He said something like, ‘You all better shut this s*** down,’” recalls longtime anti-violence activist Jamal Johnson, known for his 2021 hunger strike at City Hall to force then-Mayor Jim Kenney to confront Philadelphia’s rampant shootings, and for “Stop Killing Us,” his yearly walk to Washington, D.C., to press Congress to pass effective gun-control laws. The masked man told Johnson, who was alone at the base at that time, that he would return with reinforcements. Then he pedaled off into the night.

Johnson relayed the threat to the foot-patrollers, who hurried back to the base. Despite the warning, the men decided to stand their ground. “We didn’t leave because that

would have given the man what he wanted,” says Casher, who took the threat as a sign that Hug the Block was succeeding in changing the area’s ambiance.

The initiative, a collaboration with Johnson, was Philly Truce’s first city-wide campaign. Pickens and Casher, friends since childhood in North Philadelphia, launched the organization in 2020 after George Floyd’s murder. “When an injustice is committed [against Black Americans] by someone of a different ethnic group, there’s outrage,” Pickens says. “Where’s the outrage when [the gunmen are from] our own community?”

For its first effort, Philly Truce patrolled streets in West Philadelphia over the 2021 Thanksgiving weekend, a holiday when violence often spikes. That initiative led to far fewer shootings, as did West Philly peace patrols in 2022, according to Casher.

In 2023, the team launched Safe City Boys to mentor youth from ages 11 to 15. During the school year, the boys meet twice during the school week and on Saturdays with mentors who guide them in developing skills like emotional awareness, relationship building and conflict resolution. Safe City Boys also offers presentations from people who work in various professions as well as workplace visits. Last year, the program served 24 boys at different sites across the city, Casher says.

“We have 15 boys this year, and we expect that number to double by the summer.”

The Safe City Summit in late May brings together all the boys as well as past program participants. For this year’s summit, Philly Truce has partnered with architect Michael Spain of the Community Design Collaborative, a firm that specializes in planning resilient communities, Casher says. The summit will focus on creating neighborhoods whose design promotes peace.

“The boys will do an [artificial intelligence] exercise, actually planning a community, led by Micahel Spain,” Casher says. The summer will also include paid community service, such as tending community gardens and foot patrolling with their mentors, Casher says. The program aims to teach boys that they are responsible for how their communities look and what happens there, he says.

Philly Truce also launched an app that can put Philadelphians who see potentially violent conflicts brewing in touch with trained mediators 24/7, Casher says. Developed in 2021, the app had more than 1,500 downloads, 200 help requests and 37 de-escalations of conflicts in 18 months, according to Casher. The free app is currently on hold while being revamped for smoother communication between peace patrollers and community members trying to reach them.

Hug the Block is the organization’s most widely known effort. Using data from District Attorney Larry Krasner, Johnson, Casher and Pickens identified 77 blocks where 10 or more shootings had happened since 2015. Starting on August 22, 2023, they kept watch on one block a night for the 77 nights prior to the November 7 mayoral election to push the candidates to prioritize curbing shootings

among Black youths. Then the men and other volunteers walked the block together from 10 p.m. to 4 a.m. at 30-minute intervals, starting at the top of the hour.

The patrols were peaceful, but not quiet. Using bullhorns, the men urged neighbors to launch watch groups themselves. “Sometimes they would join us,” says Marc Anthony Postell, a Southwest Philly resident and truck driver for the Philadelphia Housing Authority who patrolled for 55 nights. “It was exhausting, but you feel good about doing something positive.”

There were moments of frustration. “If I can be here at 10 p.m. at night patrolling your neighborhood and I don’t live here, why can’t you be here?” Pickens says. Postell says that churches and nonprofits could take on the task that Philly Truce had assumed.

When an injustice is committed [against Black Americans] by someone of a different ethnic group, there’s outrage. Where’s the outrage when [the gunmen are from] our own community?”

steven pickens, Philly Truce Foundation

Hug the Block produced an immediate effect, according to Maya Stallings, adjunct professor of civic engagement at Drexel University and a volunteer with Philly Truce. Stallings compared statistics before the patrols with those immediately afterward. “We found a 64% decrease in crime overall, and no one under the age of 18 was shot,” she says.

Given the patrols’ effectiveness, Johnson, Pickens and Casher asked City Council to fund a pilot program. They propose a town watch model where paid participants patrol an assigned neighborhood and report suspicious or criminal activity.

Casher noted that patrollers from the community and the police would have a common goal, and that could improve the relationship between them.

Councilmembers Kendra Brooks and Jamie Gauthier — who joined Hug the Block patrols, along with Council president Kenyatta Johnson, and Sheriff Rochelle Bilal — favor funding a pilot program. Gauthier says that besides making neighborhoods safer, the call to action for Black men heartens her. “The men could mentor and engage our people, teach them to cool down situations before they erupt in violence.”

Through all its programs, Philly Truce aims to equip Black males and their communities with tools that increase their chances to achieve sustainable manhood, Casher says. ◆

To learn more about Philly Truce, Safe City Boys or to make a donation, visit phillytruce. com or call (267) 458-7823.

Under new federal regulations, the Philadelphia Water Department will need to remove all of its lead service lines within 10 years. Finding, excavating and replacing them may cost half a billion dollars by zane irwin

Across the country, civil engineers and water experts are bracing for new requirements announced in December 2023 by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to take effect. For the first time, water systems may be required to unearth and replace the nation’s remaining lead pipes — all nine million of them.

The Lead and Copper Rule Improvements, or LCRI, as it’s called, is the latest chapter of a decades-long push to get lead out of America’s drinking water. Despite its unassuming name, the LCRI carries dra-

matic implications for hundreds of cities. Aside from stricter water quality metrics and more frequent testing, the EPA is expecting a plan from each municipality on how they will replace all lead service lines within 10 years.

Philadelphia has between 20,000 and

25,000 service lines that would need to be replaced under the proposed rule, according to the Philadelphia Water Department (PWD). While environmental and public health advocates laud the ambitious proposal, some water quality experts in Philadelphia question whether the EPA’s demands are realistic. The saga illustrates how even uncontroversial-seeming reforms trickle through layer after layer of competing priorities and logistical hurdles.

PWD’s task is a bit like finding needles in a complex, centuries-old haystack.

People have used lead pipes since the Roman Republic, where the material’s pliability and strength lent itself to transporting water in an advanced early plumbing system. For the same reason, major U.S. cities began installing lead service lines en masse in the late 19th century.

But even then, the scientific community knew about lead’s health hazards. Studies show that children exposed to the element are more likely to suffer developmental set-

backs, nervous system damage and other ill effects.

Fears of lead in drinking water reached an apex in 2014 as the national spotlight swiveled to Flint, Michigan. Improperly treated tap water exposed nearly 100,000 people to the heavy metal. A federal emergency was declared and lead turned from an insidious public health issue to a front-page political priority.

As recently as 2021, 11.3% of tested 3-yearolds in Philadelphia had blood lead levels above the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention concern threshold of 3.5 micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood (μg/ dL), down from almost a third of children tested in 2011. When lead pipes are present, they account for around 20% of exposure, with the rest primarily coming from paint. Following a pernicious pattern in public health, the most affected communities are predominantly low-income communities of color in North and West Philadelphia.

By the time the federal government first required municipalities to track plumbing materials in 1991, cities across the country had been installing lead pipes at a large scale for almost a century — often leaving no records behind on which kinds of pipes went where.

When the Biden administration tasked water systems with documenting the material of old pipes on top of new ones in 2021, experts like Adam Hendricks took a deep breath.

“Our initial take on the inventory was that it seemed very complicated for us to complete,” says Hendricks, the applied research program manager for lead service line inventory and replacement at PWD. Besides a lack of historical data, his team faces strict standards for verification and a looming deadline of October 16, 2024.

The task has proved difficult, but not impossible. The Water Department is leveraging a citywide meter replacement project to locate more lead pipes. They’re also exploring new technologies, like artificial intelligence (AI) predictive modeling tools and experimental acoustic techniques, to find the pipes without digging up half of the city. Either way, the LCRI requires Philadelphia to excavate 400 of its 511,000 service lines just to validate the material.

Hendricks says his team aims to have an initial inventory completed before October, but many lines will be listed as “unknowns” at first. When the meter replacement project

is due for completion in 2025, they expect to bring the updated inventory to 90%. “We are going to publish as much of the information as we have,” he says.

Although the City has been working on the inventory for several years, the part of the LCRI that has public works most daunted — and advocates most excited — is the de-

Now we have a new enthusiasm for getting this job done. The reason we need to get rid of lead service lines is because we can.”

lynn thorp

national campaigns director at Clean Water Action

mand that municipalities replace all known lead service lines within 10 years.

From her post as the national campaigns director for the nonprofit Clean Water Action, Lynn Thorp finally let herself feel excited. “10 years ago, I didn’t think it was possible,” she says. With 25 years of drinking water expertise, Thorp has fought to fully replace lead service lines, even as others argue meaningful progress can come from less drastic measures.

Short of excavating all lead pipes, cities have tried several methods to prevent lead from leaching into drinking water. One popular solution involves orthophosphates, chemicals that combine with harmful materials to keep them from dissolving into the water stream.

While the EPA recommends this corrosion control strategy for systems with lead service lines, orthophosphates like those used in Philadelphia aren’t a silver bullet. The treatment is less effective when water is hot or has been sitting in the pipe for hours, and environmental organizations like Clean Water Action have raised concerns that phosphorus could harm aquatic

Scientists have known since the 19th century that lead pipes could cause poisoning, and that children exposed to lead are more likely to suffer developmental setbacks and nervous system damage.

life — and, ironically, drinking water quality — in downstream waterways.

Advocates like Thorp argue the only way to eliminate the risk of lead exposure through water is to remove all lead service lines, connectors and plumbing fixtures as soon as possible. The LCRI is the most ambitious attempt yet at realizing that goal.

Nevertheless, the new rule leaves some water supply experts in Philadelphia wondering where they’ll find hundreds of millions of dollars to do the job on time, and if that money could be better spent elsewhere.

Among them is Howard Neukrug, the former commissioner of PWD. Now teaching at the University of Pennsylvania, Neukrug has advised the EPA since it started shaping the modern Lead and Copper Rule in the late 1980s.

“Lead has a number of different points of exposure. And in my mind lead pipes [are] the very least of it,” he says. Neukrug pointed out that the bulk of lead exposure — which has plummeted in the last 50 years — comes from paint dust indoors or flecks falling into the soil.

Instead of tackling one facet of the problem on a broad scale, Neukrug argues a more effective and economical approach would be to target individual communities where children show concerning blood levels. “There should be people going out to that home … [to] do a full, comprehensive test,” he says — not just of the water, but the paint, dust and soil as well.

Then there’s the money problem. Under the new rules, PWD would have to find and replace anywhere from 20,000 to 25,000 problem pipes across the city. At $12,000 to $13,000 per service line, the City expects the project to cost up to half a billion dollars over 10 years, accounting for the cost of restoring sidewalks and inflation.

“We’re in a lot of trouble as an industry,” says Neukrug. On top of the LCRI, the Water Department is already tackling a laundry list of existing demands, like increasing dissolved oxygen levels and reducing exposure to PFAS, aka “forever chemicals,” in water.

In comments submitted in February, PWD politely urged the EPA to slow down. “The 10-year replacement timeline … is not feasible due to financial concerns, limited resources, and competing regulatory priorities.”

“If the federal government really wants

The part of the LCRI that has public works most daunted — and advocates most excited — is the demand that municipalities replace all known lead service lines within 10 years.

to do this, they should pay for it,” says Neukrug. As part of Biden’s 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the City received $35 million for projects supporting lead service line removal — a far cry from the estimated half a billion required. While PWD has applied for earmarks, grants and low-income financing to help close the funding gap, Hendricks admitted the LCRI will most likely lead to rate increases for residents.

Hendricks emphasized that Philadelphia’s water is stringently tested and treated, with extensive facilities and a consistent track record of testing below the danger zone on a range of criteria.

And that’s not just coming from the Water Department itself; Eastern Pennsylvania director for Clean Water Action Maurice M. Sampson II says Philadelphians have it comparatively good.

“There are outbreaks of waterborne illnesses happening in small water companies,” he says. “That doesn’t happen in Philly.”

Yet advocates insist that despite the costs and competing demands, it’s crucial to strike while the iron is hot. “Now we have a new enthusiasm for getting this job done,” says Thorp. “The reason we need to get rid

of lead service lines is because we can.”

Though the LCRI hasn’t yet been finalized, “people should expect to start hearing from us,” says PWD spokesman Brian Rademaekers. Whether it’s during a routine water main replacement or on a new accelerated timeline that would require about 400 pipe excavations before October 2024, the LCRI requires providers to pursue property owners’ approval to do individual replacements, which typically take less than a day.

In the meantime, you can get your water tested for free via the Water Department, or check your service line for lead. The City will replace the line free of charge if they are already changing out the water main on your street; otherwise, they offer a zero-interest loan to have a private contractor take care of it.

Unless and until the pipe is fully replaced, there are ways property owners with lead service lines can minimize their risk of exposure. Since lead is more likely to leach into water after sitting in the pipe for six hours or more, it’s a good idea to run cold water for at least three to five minutes before using it in the morning.

But if all goes according to plan under the LCRI, these measures could be relics of a bygone era for the next generation. ◆

Community volunteers, with the help of nonprofit and private sector, create urban pollinator habitat

There’s a buzz around the new native plant habitats at Wharton Square Park in Point Breeze, and it’s spread all the way to Harrisburg.

On April 30, the Friends of Wharton Square Park, in partnership with the Penn State Extension Master Watershed Stewards of Philadelphia County, received the Governor’s Award for Environmental Excellence for the volunteer-built gardens — the only Philadelphia-specific recipient.

“Our win speaks to the urgent need for more natural spaces, more native plants and more greenery in communities like Point Breeze that suffer greater consequences from climate change, like flooding, poor air quality and negative psychological and educational outcomes,” Stephanie Gregerman, project organizer and Point Breeze resident, says.

In June 2023 a community event was held where over 40 volunteers prepped soil with compost, planted, mulched and watered 600 plants — 16 different species — for a network of eight native plant gardens in high-visibility areas.

“It was an ambitious project, especially because we wanted to create a planting event that provided more than just a volunteer opportunity — we truly wanted to teach more about the importance of native plants and to inspire our neighbors,” Gregerman says.

The gardens are designated a Watershed Friendly Property and a Pollinator Habitat through the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation, an international nonprofit that provided the plants at no cost.

The project was designed to maximize the environmental impact of unused and underused areas, creating habitats for pollinators, and better supporting the urban ecosystem and resident health. The

gardens also fill a large gap in native habitat by connecting Center City spaces like Rittenhouse Square and the Southwest Center City Pollinator Pathway to bigger areas like FDR Park.

“It’s always amazing to see how fast native pollinators and birds show up wherever we plant native plants, even in the city,’” says Anne Boyd, founder of the Southwest Center City chapter of the national Pollinator Pathway and a team leader for the layout and planting of the Wharton Square Park project. “Human health and well-being depends on our public green spaces, but our urban parks are also a place to support and experience biodiversity close to home.”

Vicinity Energy, a sustainable district energy provider located in Grays Ferry, funded a $1,700 zero-emissions water wagon machine which allowed volunteers to water in areas of the park that previously could not be reached.

“Vicinity is thrilled to partner with the Friends of Wharton Square Park. It’s truly our honor to have supported the funding for the water wagon machine, empowering the team to breathe new life into previously neglected areas by cultivating native plant species gardens,” states Matt O’Malley, chief sustainability officer of Vicinity. “We are proud to stand shoulder to shoulder with our neighbors in building a cleaner, greener and more sustainable Philadelphia.”

“This award is really just the start,” Gregerman added. “It will hopefully be the catalyst for more native plantings, connecting places like Schuylkill River Park, Julian Abele Park and Bartram’s Garden … The real dream is to see native habitat plantings like this across Philadelphia.” ◆

A ceremony recognizing the award in Point Breeze on PA Native Species Day on May 16 is planned, with state and Philadelphia city officials expected to attend.

This award is really just the start … The real dream is to see native habitat plantings like this across Philadelphia.”

— stephanie gregerman, project organizer and Point Breeze resident

How well do you know your neighbors? In a city as big as Philadelphia, there are always more folks to meet, but let’s talk about more than just Homo sapiens

Maybe you know your local squirrels. Are they simply entertaining, or do they steal your tomatoes? Perhaps you hear the starlings singing from telephone lines and squabbling as they pick the scraps from chicken wings. House sparrows may wake you up this time of year with incessant “cheeps” at dawn. And have you noticed all the pigeons flying among the rooftops?

Opossums, raccoons and foxes might cross your path after dark, and if you’ve got a yard, deer could visit to eat your flowers. You might have a burrow beneath your storage shed dug by woodchucks, who, together with rabbits, help

themselves to your lettuce sprouts.

And while some of our wild neighbors are born and raised here, plenty of others, in particular migratory birds, are passing through. They touch down on heroic journeys bridging habitats as far away as the Amazon rainforest and the boreal forests of Canada. They are guests in our city. How can we be good hosts?

May is a particularly good time to think about how we can make our city home to our wild neighbors. We can think about wildlife when we design our gardens. We can make sure our pets don’t kill or scare away birds. We can plant native plants that build the food chain from the bottom up. Spring is upon us. It’s a beautiful day in the neighborhood.

Bird Safe Philly is on a mission to prevent window collisions, a leading cause of death and injury

It’s 7:30 a.m. on a Friday in late March and Stephen Maciejewski is walking around Center City looking for dead or injured birds. He isn’t hoping to find any. But it’s spring migration, a time when millions of birds pass through the city on their way north. Maciejewski knows many of them are bound to strike the countless glass windows in Philadelphia’s urban core.

When that happens, Maciejewski, a volunteer with Bird Safe Philly, intends to document it. Over the course of his two and a half hour shift, which he begins daily at 5:30 a.m., he checks the perimeters of 18 buildings in the area. If he discovers an injured bird along his route, he takes it to a wooden box in a nearby building’s loading dock, where it will rest until another volunteer can drive it to a wildlife clinic for rehabilitation. If he discovers a dead bird, he places it in a bag, and eventually brings it to the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel Uni-

For birds, glass equals death. It’s just a matter of time before they’re gonna kill themselves flying into glass.”

STEPHEN MACIEJEWSKI

Bird Safe Philly

versity, where it will be used for research. Either way, he takes meticulous notes on his finds, recording the impacted species, the time of the collision and the building where it occurred, among other details. In just one four square block area in Philly,

1,000 such collisions happen every year, according to Bird Safe Philly’s data. And across the U.S., as many as one billion collisions occur annually. It’s the third biggest threat facing birds, after habitat loss and outdoor cats.

Those collisions, Maciejewski knows, aren’t inevitable. Preventing them is the mission of Bird Safe Philly — a partnership of the Academy of Natural Sciences, Audubon Mid-Atlantic, Delaware Valley Ornithological Club, National Audubon Society, Valley Forge Audubon Society and Wyncote Audubon Society. The organization formed in 2020 after a mass collision event in which thousands of migratory birds died after hitting buildings in Center City. Maciejewski was walking the streets that day and documented the destruction. Better data on the frequency and location of such bird collisions, he hopes, can inform interventions to stop them in the future.

“For birds, glass equals death. It’s just a matter of time before they’re gonna kill themselves flying into glass,” he says. “A lot of people kind of ignore it, but you really can’t ignore it when you see it every day.”

In the years since its formation, Bird Safe Philly has been busy. The team started Lights Out Philly, an initiative that enlists property managers to voluntarily turn off or block as many external and internal building lights as possible at night during spring and fall migration. Turning off lights protects birds from nighttime collisions, potentially reducing deaths up to 80%. Today, more than 100 buildings are participating in the program.

“We didn’t realize the impact that we were having and [Bird Safe Philly] opened our eyes to it,” says Rich McClure, a member of Building Owners and Managers Association of Philadelphia (BOMA), a commercial real estate organization that has partnered with Bird Safe Philly on the Lights Out Philly program. “And it was an easy lift.”

Organizers with Bird Safe Philly are still working to get more buildings on board with Lights Out Philly. But they know that even if all the buildings in the city went completely dark at night, the problem wouldn’t be entirely solved. That’s because birds can also hit buildings during the day.

“Artificial light at night is still a big problem, but the glass is a bigger problem,” says Keith Russell of Audubon Mid-Atlantic. “It’s proliferated to the point where every new building is full of glass, and the glass has

been perfected since the ’60s to be extremely even and flat. Because it’s now so perfect, it creates perfect reflections, and that makes it much more susceptible to birds flying into it.”

To prevent those collisions, property managers can apply dense patterns to windows, cover them with paint or vinyl, or hang screens on them. And with Bird Safe Philly’s help, some buildings have been adopting some of those methods. At Springside Chestnut Hill Academy, the organization helped third graders apply adhesive markers and bird decals to the cafeteria windows, and helped the Briar Bush Nature Center in Abington, Montgomery County, and the Pennypack Ecological Restoration Trust apply the same solution to several buildings situated in a wooded preserve. In 2023, along with Center City District, the Bird Safe team helped Sister Cities Café — a building enclosed by glass on three sides that faces tree-filled Logan Square — cover its walls with small dots, which they say drastically reduced the number of collisions.

There’s more action on the way. Andrew McDougall, a spokesperson for the National Park Service, told Grid that the agency will install “a bird-friendly film or etching” on the south end of the Liberty Bell Center sometime this year and will redirect the building’s outdoor lights downward instead of upward in an effort to reduce bird collisions. “We would eventually hope to do the same for the Independence Visitor Center. The National Constitution Center, I think we have to take a little more look at,” he says.

Generally, convincing organizations with an explicitly environmental focus (like nature centers) to retrofit their windows is not a tough sell. It’s more difficult when it comes to those that don’t share that mission. Turning

off the lights at night can save property managers hundreds of thousands of dollars per year, but retrofitting windows comes with a price tag — one that Bird Safe Philly has found many are slow or unwilling to accept.

Take the Ciocca Subaru dealership in Grays Ferry, a building whose tall glass windows reflect the adjacent Stinger Park, had at least 79 collisions in the fall, more than any other building Bird Safe Philly monitored. It has not yet intervened to prevent bird collisions, despite multiple meetings with Bird Safe Philly. (Ciocca Subaru did not return a request for comment.) The Philadelphia Art Museum, whose glasswalled sculpture garden has been the site of numerous bird collisions, has “considered installing measures to deter birds from flying into the glass, but has not yet decided to install,” according to a spokesperson.

“[Window retrofits] are a cost, and they’re a complete look difference,” says Don Haas, a member of BOMA Philadelphia. “Especially if you’re on the first floor, a lot of times it’s retail. And if it’s retail… you don’t want to be blocking the optics.”

In cities and states across the country, legislation is superseding those aesthetic and economic concerns, making bird-safe design and practices mandatory for some buildings. The Maryland Sustainable Buildings Act, for instance, requires all newly-built, acquired or renovated state-owned buildings using state funds to use bird-friendly windows and lighting. In New York City, a law forces City-owned buildings to turn off the lights at night during migration season.

Stephanie Egger, a member of Bird Safe Philly, says similar legislation at the city or state level here is needed, but making it possible is an uphill battle. It would be especial-

ly difficult to force the change for privately-owned buildings; even Haas, a Bird Safe Philly partner, told Grid that he’s opposed to legislation that would require buildings to make accommodations for birds.

“[Legislation] would be a huge effort and we’re really far away from being able to make existing building owners do anything,” says Egger. “This is where relationship building comes in and working cooperatively with building owners and just trying to convince them that this is the right thing to do.”

At the end of his shift, Maciejewski heads to the Academy of Natural Sciences where he opens a chest freezer holding plastic bags filled with dead birds. In one bag, there’s an American woodcock, found dead on the east side of the 58-story glass Comcast Center on March 14. In another, there’s a brown creeper, found dead on March 15 on the building’s south side. “I’m like the avian undertaker,” he says.

For a bird lover like Maciejewski, it’s upsetting, finding “these really beautiful, intricately-colored birds dead again and again and again.” It’s more upsetting, still, for him to think about how many birds in cities around the world are meeting the same grim end. “The problem is not just in Philadelphia. It’s a monumental, universal problem. It’s hard to wrap your brain around it. We have to cut down on glass, but we’re addicted to it,” he says.

It’s a sobering thought, but it’s not enough to stop Maciejewski from hitting the streets again tomorrow, rain or shine. After all, he knows, there are still some birds that can be saved. “You have to go out there and keep on trying.” ◆

Naturalist and author Scott Weidensaul discusses the miracle of migration and how to protect our feathered friends INTERVIEW

BY BERNARD BROWNNevermind the wildebeest of the Serengeti or the caribou of western Alaska; the greatest wildlife spectacle on Earth takes place over our heads twice a year.

Early May marks the high point of the spring bird migration season, when billions of birds around the world ranging from hummingbirds to eagles work their way north. Hundreds of millions of birds fly above and through Philadelphia via the Atlantic Flyway, essentially a bird superhighway following the Atlantic coast of North America.

In “A World on the Wing: The Global Odyssey of Migratory Birds,” Scott Weidensaul reveals the mind-blowing journeys birds make, as well as the threats that humans pose to these globe-spanning creatures. Weidensaul has devoted his life to studying and writing about birds. His work has taken him as near as the mountains of eastern Pennsylvania and as far as Denali National Park in Alaska. He talked with Grid about the amazing migrations of birds and what we can do to help them.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

There are so many amazing bird migration accounts in “A World on the Wing” and in your earlier book “Living on the Wind” [1999]. Could you pick one that amazed even you, and that someone in Philadelphia could observe? The easiest thing to do would be to go down to Cape May in the springtime when you have shorebirds, including red knots that have spent the winter at the southern tip of South America, flying up to their breeding grounds in the High Canadian Arctic. They’re making about an 8,000, sometimes 9,000-mile, one-way trip from the furthest extent of

the Western Hemisphere in the south to almost the furthest extent of the Western Hemisphere in the north. They stop off at the Delaware Bay for a couple weeks in May where they need to more or less double their weight, feeding traditionally on the eggs of horseshoe crabs. Of course the horseshoe crab population has been devastated in the Delaware Bay by 20 years of overfishing. The red knots have suffered badly. Their population is a fraction of what it was back in the late ’80s and early ’90s.

They are never seen on the ground in Pennsylvania, but almost all of those red knots are over the airspace of Pennsylvania on their way flying north and west into the Central Canadian Arctic. So just in the last couple of years, thanks to new tracking technology, we’ve come to understand that the airspace of Pennsylvania is critical habitat for these birds.

And so as we make decisions about things like ridgetop wind turbines, that’s something that I think we need to at least take into account. I’m not saying we shouldn’t be putting wind turbines up there, but we shouldn’t overlook the importance of airspace as a critical habitat for a lot of these migratory birds.

You write about how technological advances have revealed so much about bird migration in recent years. Could you zero in on one of these advances: the MOTUS network of radio receivers? It uses two pre-existing technologies: highly miniaturized VHF [very high frequency] radio transmitters — I mean literally light enough in some cases you can put them on a butterfly — and then automated receiver stations that basically look like somebody forgot to take down their old-fashioned television antenna. All of the transmitters broadcast on the same frequency, but each one broadcasts a

unique identification code.

So as they’re picked up by these receivers, the computer can tell whether it’s a whiterumped sandpiper that was tagged on the shores of James Bay, or a gray-cheeked thrush that was tagged in the jungles of Colombia, or a scarlet tanager or wood thrush that was tagged in the forest of northern New Jersey. It’s revolutionizing our ability to track most migratory birds.

What can people in cities like Philadelphia do to help migrating birds? Most birds, even the ones that are normally active in the daytime, migrate after dark. Cities draw migratory birds into them, literally like moths to the flame, due to the urban light pollution at night — especially in the fall, when most of the birds migrating are naïve young birds on their first migration.

Cities like Philadelphia have undertaken campaigns to get people to turn off their lights at night and control light pollution. That’s terrifically important because we lose probably about a billion birds a year in North America to building strikes and window collisions.

And we’re coming to understand the degree to which urban parks and greenspaces are vital liferafts for tens to hundreds of millions of migratory birds every year. So there’s a way to mitigate some of the damage, and that’s for us to start managing our parks and urban greenspaces for birds as well.

I’ll throw you a softball: what about our pet predators? For the love of God, if you have a cat, please keep it in the house. Cats are, pretty much without a doubt, the single most damaging human-related cause of bird death, somewhere between 2 and 4 billion birds a year. So more than windmills, more than lighted skyscrapers, more

than speeding cars. All of that is additive on top of the natural dangers these birds face.

Anything we can do to reduce that human-related mortality is a plus, and cats ought to be the easiest kind of low-hanging fruit. All you’ve got to do is keep the door closed. And I don’t care if you don’t think your cat kills birds. Your cat kills birds — and voles, and lizards and all sorts of other little things as well.

It’s also true that dogs are surprisingly disturbing to birds. They don’t eat birds the way cats do. Birds can learn very quickly

Thanks to new tracking technology, we’ve come to understand that the airspace of Pennsylvania is critical habitat for these birds.”

SCOTT

in parks that the people are just going to ignore them, but there’s a lot of research to show that even a leashed dog, even a well-behaved dog, is very disturbing. It scares the birds away.

I’m not suggesting that we ban dogs from our city parks. But on the other hand, if we are serious about creating an area that is good for birds, we might want to consider restricting dog walking in that part of the park.

Birds are everywhere and, especially if we make fairly small accommodations, cities can be good places for birds.

I know that it’s easy to drive people away if they feel like you’re attacking their pets. How do you challenge people without alienating them? Well, it can be hard because anything that is emotionally close for a person can become an emotionally polarizing issue. That’s why the third rail of bird conservation has always been cats. And unfortunately, as I say sometimes the choice has been made to just ignore the issue. I have probably put my foot in my mouth more than once in making my feelings known to people who I thought should know better than what they were doing.

I imagine the same is true for some of the powerful people you end up birding with, who have held high positions in government or in corporations that are involved in environmental destruction, the sort of people who go to the World Economic Forum in Davos every year. These are not the kind of people I usually run around with. We poor freelance writers don’t get invited to Davos. But I’ve been asked to hang around with the former chair of the Fed and the head of the World Bank. I’ve got the email for the CEO of TikTok. These are potential converts to changing things for the better for the environment. I think enlightened self-interest goes a long way, but also just the simple act of showing them a bird, really showing them a bird for the first time.

To see like a rookery full of nesting egrets, and ibis, and spoonbills, on the Southeastern coast on a spring day, when the alligators are bellowing, it can be a life-altering and perspective-altering experience. My job is to let the birds be the best ambassadors that they can be. ◆

Data suggest monarch butterflies are not at great risk — and conservation efforts might be doing harm

BY JESSIE BUCKNER

Nature enthusiasts often speak of a “spark species” that inspired their love of nature; it’s hard to think of one more popular than the monarch butterfly, which captivates thousands across North America with its flashy colors and extraordinary annual migration.

These iconic butterflies hold a name brand recognition not given to most insects. We see them fluttering about Philadelphia and guest starring in exhibits at the Academy of Natural Sciences and Tyler Arboretum. Their migration is studied at the nearby Cape May Bird Observatory, where

people can enjoy their beauty and even participate in data collection.

All this attention on monarchs can be traced back in part to 1990, when Mexican officials released data showing a decline in overwintering populations that was believed to indicate a significant decline in the whole monarch population. This spurred an entire movement to “Save the Monarchs,” prompting articles, conservation efforts and funding. The monarch became an icon of conservation far surpassing any other insect.

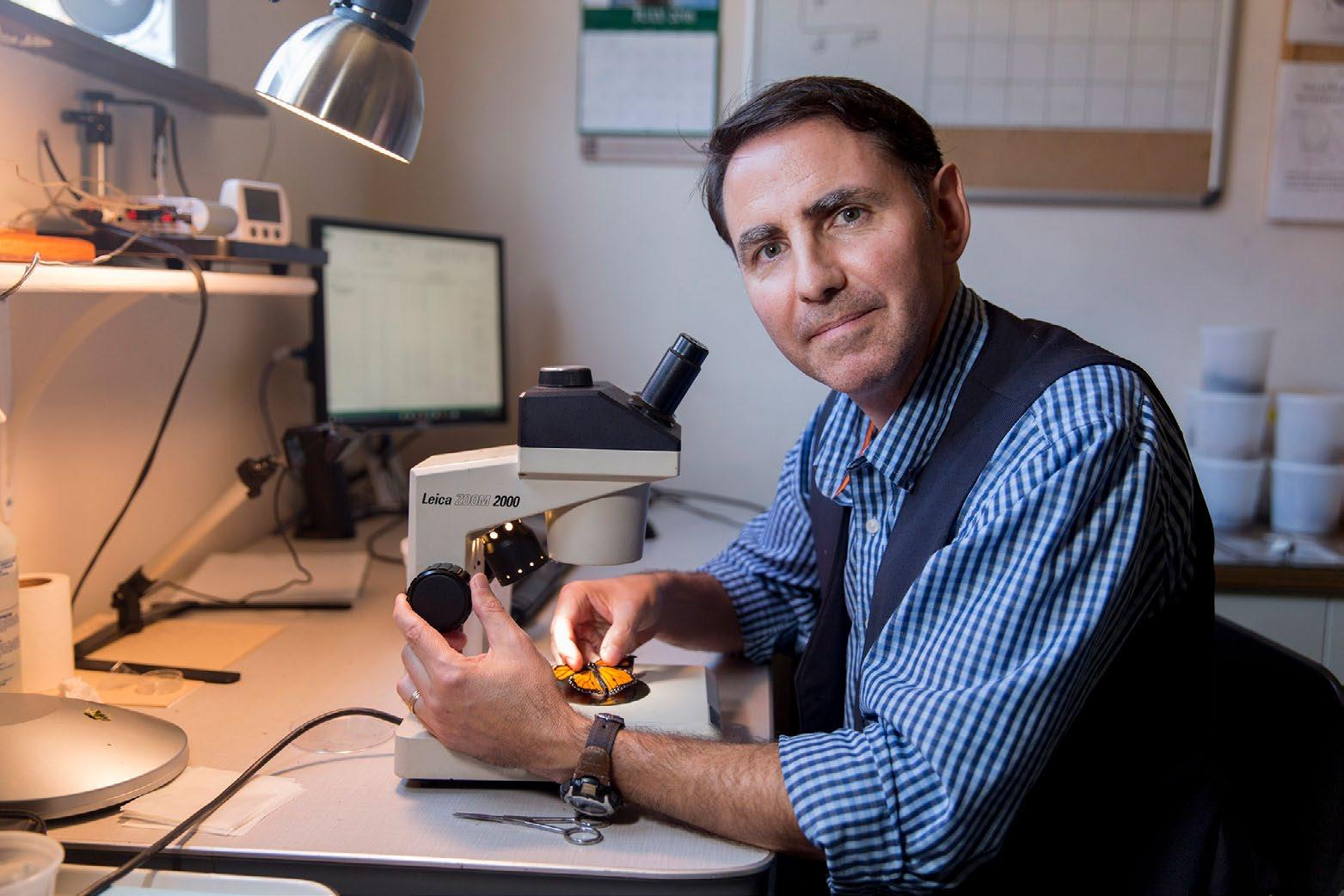

But as scientists dig into the data, a question has arisen: do monarchs actually need saving?

This year, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service will decide whether or not to list monarchs as an endangered species, but many scientists are saying the data don’t support the narrative of decline. Findings show that the overall population of monarchs remains steady — despite changing migration patterns and the spread of a debilitating parasite, which some scientists say are causes for concern. For weighing less than one gram, these beautiful butterflies have sparked a ton of controversy.

The complex life cycles of monarchs may explain some of the confusion in understanding their abundance. Each year provides four

Andy

There’s an amazing amount of attrition during that fall migration — some natural, some anthropogenic, but it is massively underestimated.”

ANDY DAVIS

University of Georgia

generations of monarchs, each going through four life stages. In the springtime, a female monarch lays 100-300 eggs on milkweed, which is also their favorite food source. These eggs hatch into baby caterpillars that spend their time munching the milkweed until it’s time to pupate or transform into a chrysalis. As the chrysalis hangs from a stem or leaf via silk threads, the metamorphosis occurs until the vibrant monarch butterfly emerges after eight to 15 days.

That “first generation” butterfly will live about two to six weeks and die after laying eggs for the second generation, which will do the same thing into the third generation. Each generation moves a little bit further north until the fourth generation changes the game plan. This generation, typically born in September and October, goes into reproductive diapause, meaning they hit pause on mating and laying eggs. Instead, they fly up to 3,000 miles south to spend the winter in central Mexico where they clus-

ter on oyamel fir trees in spectacularly large groups. In early spring, the butterflies begin their journey north to start the cycle all over again. The fourth generation can live up to nine months to facilitate this process.

So how do scientists determine the population of monarchs when their lives are so complex? Because monarchs cluster while they overwinter, traditionally many scientists studied these populations and inferred that the overwintering population should reflect the overall population. But Andy Davis, a research scientist from the University of Georgia, says this operates on the assumption that the entire monarch population makes it to Mexico.

“It’s as if all the monarchs just jump on a bus and it arrives in Mexico and lets them out and they all hang out in the trees so they can be studied, the entire population,” he says. “But it’s probably never been that. There’s an amazing amount of attrition during that fall migration — some natural, some anthropo-

genic, but it is massively underestimated.”

If scientists look at only the overwintering population after the population die-off that occurs during migration, they miss the incredible resilience and quick bounce-back occurring during the breeding season. As climate and land uses change, so does the variability of when and where the monarchs will be most and least robust in their population, and that needs to be accounted for, Davis says.

While some data sets show decline in the overwintering population in Mexico, Davis and his team used extensive data spanning 1993 to 2018 from across the entire geographic range of monarchs to model the population. Their advanced statistical analysis showed that the population remains “bouncy” with no real decline. Davis says the data pronouncing the decline of monarchs isn’t wrong, but “it’s just one snapshot of one time point in a very complex life history.”

Another study by Josh Puzey, a plant biologist and genetic scientist at The College of William & Mary who studies monarchs and milkweeds, says something similar: the genetic diversity of monarchs has not significantly decreased. The census population — what most people mean when they say population — refers to the actual number of individuals within a population, whereas the genetic population reflects the diversity among individuals of a species. The genetic population can be a pretty good indicator of whether or not a species has experienced a “bottleneck,” or a significant population size reduction that in turn limits genetic diversity. Because the genetic diversity of monarchs has not significantly decreased, Puzey and his team of scientists, including monarch expert Anurag Agarwal, infer that it is unlikely their census population has experienced a significant decline either.

“If any decline is occurring, it is a natural contraction,” says Puzey. He reflects on the “snapshot” that Davis referred to, versus the longer time scales found in natural cycles and how our perspective of the monarch populations can be colored by this complexity. “As humans, our time span is limited in how we observe these occurrences.”

He also points out that the monarch population that scientists have observed for the last 200 years may have experienced a human-caused expansion. He refers to work

by Lincoln Brower and the idea that when Europeans came to the eastern United States, it was heavily forested without open fields and large populations of milkweed. There are no mentions of monarch butterflies by naturalists until 1857, as the westward expansion was underway and Europeans became more familiar with the great plains and open areas of the Midwest. Europeans cleared great swaths of forests in their colonization and in doing so created monarch habitat that led to an increase in population.

Puzey wonders, what is the baseline? “This is where we get into conservation philosophy. Are we trying to conserve current populations, or trying to get to historic levels? It’s not as simple of a story as we make it out to be, there are many layers.”

Adding to the complexity, some widely adopted monarch conservation strategies are actually proving to be detrimental. As is the case with many things in nature, people may now be loving monarchs to death.

Many conservation groups encourage people to raise monarchs indoors and then release them, which sounds great in theory. But concentrated populations of monarchs raised indoors in close proximity are more likely to contract and spread a debilitating parasite called Ophryocystis elektroscirrha (OE). Effects of the parasite can range from shorter life spans and difficulty flying to the inability to develop properly and emerge from the chrysalis. Beyond the OE calamity, studies suggest that the captive reared monarchs don’t fly as well as wild monarchs to begin with. Davis worries about these poor flying genetics mixing with wild genetics and contributing further to the migration attrition.

Another issue is the planting of non-native milkweeds. Good-hearted folks hear that they’re supposed to plant milkweed for monarchs and go running to their nearest store where more often than not, the only available milkweed is tropical milkweed. (The three species most common to the Philadelphia region are common milkweed, butterfly weed and swamp milkweed.) Tropical milkweed can provide food and shelter to monarchs, but it is not in sync with local seasons and blooming periods. It can bloom throughout fall and winter and trick monarchs into stopping their migration or breeding outside of the appropriate season when they are not likely to survive

due to cold weather. Tropical milkweed also plays a role in perpetuating the spread of the OE parasite.

Davis worries that the spread of misinformation around monarchs and the efforts to save them may be what actually leads to their decline. What he calls people’s “emotional affair with monarchs” seems to be superseding the scientific evidence telling us a more complete story about monarch populations and how to actually support their health and biodiversity in general.

Davis suggests that if people really want to help monarchs and all insects, and in turn the entire food chain, they should take a section of their lawn and re-wild it — stop mowing and let the grass grow tall, or put in native plants or wildflowers. Mount Moriah Cemetery horticulturalist Joanna Cosgrove says that it’s a challenge to get gardeners to plant native milkweeds because they aren’t as showy as the tropical varieties and can take over a space. But, she says, practices like removing the seed pods before they disperse can keep them in check.

Anecdotally, in her years stewarding Mount Moriah, Cosgrove has seen very few monarch caterpillars or eggs on the milkweed she tends. But quantitative data from local studies at Cape May Bird Observatory and from veteran citizen scientist Gayle Steffy, who studied monarchs around southern Pennsylvania for 18 years, show that monarchs continue to thrive here as well. The observator y’s Monarch Monitoring Project Annual Report 2023 states:

“Wind and weather, alongside several other factors, can lead to varying monarch numbers in Cape May from year to year. Despite fluctuations in monarch numbers in Cape May, the average number of monarchs appears to be consistent over the past 30 years.”

To observe monarchs in migration locally, Adehl Schwaderer, the Monarch Monitoring Project program coordinator for the Cape May Bird Observatory, recommends that visitors come in September and October on a day with northwest winds. She takes a different view than Davis on popular conservation efforts. “There’s a delicate balance to being an outdoor educator. You have to meet the public where they’re at and not give them absolutes or scare them away,” she says. They do captive rearing at the observatory for educational purposes, but Schwaderer recognizes that there needs to be caution in how this is presented to the public. Everyone can agree that the story is not one dimensional.

While the current stability of monarchs provides good news, a larger “insect apocalypse” plays out in the background. Monarchs can continue to be the “spokesbug” for the beauty, complexity and importance of insects — but with the understanding of their relative abundance and health. One hope is that interest in their conservation may shift to populations in more dire need. Most simply however, scientists just want the data to be accepted without any embellishment or agenda.

Ladybugs are very beneficial to gardens and farms, but the most prevalent species is invasive and has crowded out its cousins

BY BERNARD BROWNWho doesn’t love lady beetles (aka ladybugs)? They are bright and cheery with that cute, round shape, plus they help gardeners by gobbling up plant-sucking aphids. There appear to be plenty of them; they’re not hard to find outside from spring through fall, and at the end of the growing season, they often make themselves unwelcome inside by squeezing en masse through gaps in walls and windows.

Unfortunately, their abundance masks a decline in native lady beetle biodiversity. Most of the lady beetles you’ll see are of a few exotic species, while several once-abundant native species are hard to find.

These exotic lady beetles didn’t get here on their own. We released them on purpose as biological control agents meant to control smaller insects without the use of pesticides. Aphid-plagued farmers introduced harlequin lady beetles (Harmonia axyridis) as far back as 1916, and they were reported as established starting in 1988. Today, more than half of the lady beetles reported on iNaturalist in Philadelphia are harlequins, which can appear in a variety of colors and patterns in addition to the classic black-spotted red.

Harlequin lady beetles are like Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, according to entomologist and ecologist Mike Raup. In their Dr. Jekyll moments they can work through a patch of aphid-ridden plants and devour all the pests.

“But we’ve also got Mr. Hyde,” Raup says. “It rules the roost in terms of lady beetles.” That native lady beetles such as the nine-spotted lady beetle have declined just as exotics have become more abundant might have been a coincidence (and, as Raup points out, all of this has happened in habitats heavily shaped by humans), but harlequin lady beetles eat the same food and eat the eggs and larvae of the native lady beetle species.“There is good correlative evidence

that as Harmonia populations increase, the [populations] of other indigenous and non-native ladybird beetles decline,” he says. “It also eats other beneficial insects such as lacewing and hoverfly larvae.”

Biological control (importing predators and parasites) might still have a role to play in controlling unwanted insects, but today the importation of new species is much harder than it used to be. That’s a good thing

according to Kelli Hoover, an entomologist at Penn State who researches solutions to recently-invasive insect pests such as the hemlock woolly adelgid and the spotted lanternfly. It can take more than 10 years of research to make sure that any new bug will afflict only the target species and not become the next harlequin lady beetle. “It’s not easy, but it’s why we don’t have more disasters,” she says. ◆

invasive and abundant

Nine-spotted lady beetle (Coccinella novemnotata): native, once the most common in the region, hasn’t been documented in Pennsylvania since the late 1980s

Seven-spotted lady beetle (Coccinella septempunctata): an invasive from Europe that became common here as the nine-spotted lady beetles were declining

Spotted pink lady beetle (Coleomegilla maculata): native and not as round as other lady beetles

Checker spot lady beetle (Propylea quatuordecimpunctata): introduced from Eurasia into eastern Canada in the 1960s and has spread out from there

Polished lady beetle (Cycloneda munda): native, smaller than the harlequin lady beetle and with small “C”-shaped markings just above its head

Twice-stabbed lady beetle (Chilocorus stigma): native, likes to stay up in trees

Native plants and organically-based repellents can keep deer from making a feast of your garden

BY EMILY KOVACHEven the most dedicated naturalists have their boundaries when it comes to cohabitating with wildlife. And for many home gardeners, deer are enemy number one. It’s possible to acknowledge that we’ve largely taken over deer habitats and, simultaneously, feel a potent ire while watching your landscaping efforts blithely munched by these creatures.

According to Penn State Extension, there are approximately 1.5 million white-tailed deer living in Pennsylvania, including in urban and suburban areas. And deer are intensely voracious: between spring and fall, they consume between 6 and 8% of their body weight each day, mostly foliage, twigs, shrubs and wildflowers. In areas where deer have over-eaten the forests or woodlands are scarce, farms and residential gardens are a ready source of food.

What are the safest and most effective ways to politely say “buffet’s closed” to the local deer population in your area? One natural, sustainable and easy method is planting your garden with deer-resistant native plants.

We consulted Gregory Tepper, senior horticulturist at Laurel Hill Cemetery and avid gardener, for advice on this topic. After all, he’s written the book on this subject, “Deer-Resistant Native Plants for the Northeast,” and often teaches related courses and

workshops at places like Mt. Cuba Center and the University of Delaware.

“‘Deer-resistant’ is defined as plants that the deer resist eating either because of taste, smell, toxicity or a physical characteristic such as a tough texture,” Tepper explains. “Learning about and choosing the plants

that the deer really don’t like to eat gives you an advantage as a gardener.”

Some deer-resistant native plants that Tepper suggests include:

• Anise hyssop (Agastache foeniculum): a perennial plant in the mint family with a licoricey smell.

Choosing the plants that the deer really don’t like to eat gives you an advantage as a gardener.”

GREGORY TEPPER author and horticulturist at Laurel Hill Cemetery

• Christmas fern (Polystichum acrostichoides): an evergreen fern with glossy fronds.

• Eastern bluestar (Amsonia tabernaemontana): a perennial featuring clusters of pretty, starshaped flowers. “In all the years I’ve grown it, I’ve never seen deer ever bother it in season — they just avoid it,” Tepper says.

• Spreading sedge (Carex laxiculmis): the mounds of this dense, grass-like plant naturally spread, making it great for ground cover.

• Summersweet (Clethra alnifolia): in the summer, this shrub blooms with stalks of white flowers with a rich perfume. “It smells so heavenly. We like the smell but the deer don’t,” Tepper notes.

• Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum): a perennial bunchgrass sprouting reddish-purple seed heads in late summer.

• Yarrow (Achillea millefolium): this perennial flowering plant thrives in hot, dry conditions, features different color blooms and is known for attracting butterflies.

If you really want to plant flowers that deer love, like roses, phlox and hosta, you can mix them in among deer-resistant plants — or, as Tepper advises, spray them with an organically-based repellent that’s safe for the plants, humans and pollinators. Brands that he trusts include Plantskydd, Deer Stopper and Deer Scram. Another repellent, Bonide Repels-All, can also dissuade groundhogs, chipmunks, rabbits and squirrels from hanging out in your garden.

Tepper notes that some are critical of using any of these methods to keep deer away. But he argues that the animals can be extremely destructive in both home gardens and at institutions with large gardens, such as Laurel Hill.

“We’re in a modern situation where the deers’ numbers way exceed what the landscape and woodlands can support,” he says. “It’s not like we can have hunters come here and hunt, so using repelIents is the safest way for us and the animals.” ◆

“Camera trap” student project shows the hidden but rich biodiversity of the Philadelphia metro areaBY BERNARD BROWN

Who is walking around the neighborhood while you’re not looking? Humans share the city and suburbs with a cast of other mammals that do their best to avoid us by only coming out at night.

To see these shy beasts, scientists use infrared-triggered, battery-powered cameras. In a setup often called a “camera trap,” they can help gather information about what critters are living out of sight around us.

In late January and early February, students from Villanova University’s Urban Ecology class taught by ecologist Lauren Lynch placed 15 cameras in a range of urban-to-rural settings to learn more about how the local mammals inhabit these varying landscapes. Grid talked to some of the students about what they learned. They discussed how wildlife species living

in and around cities can be classified by how well they take to living in urban settings. Urban avoiders, like mountain lions, don’t do well in cities. Urban adapters, like raccoons and gray squirrels, can thrive in cities or in the countryside, while urban exploiters, like house sparrows and brown rats, are more at home here than anywhere else.

“Our goal was to quantify the bio-abundance and biodiversity along an urban

gradient in Philadelphia,” says senior Michael Simeone. He says they didn’t find a big difference in abundance or diversity across the sites, but “we noticed a change in mammal composition,” with some species being more or less common depending on the type of site. The size of the animals also varied based on how rural or urban the site was. “There were more smaller animals in urban sites, and there were more deer the

more rural we went,” he says. The students estimated that they got pictures of about 70 different deer at Ursinus College.

“In rural sites, we saw few species other than deer, but in closer [to the city] sites we saw some mammals in the mid range of size,” Simeone says. These included foxes, raccoons and in a surprise star turn, a coyote photographed at The Discovery Center in East Fairmount Park.

Brent Jenkins, a junior, says they placed camera traps at Kaskey Park (featuring the Biopond) on the University of Pennsylvania’s campus, as well as at the Discovery Center. There, they found other signs of the wildlife living alongside the coyote. “We saw a good amount of footprints and determined that they were raccoons.”

Brendan Cottingham, senior, says that when he’s back home in New York City and

traveling with a Boy Scout troop he volunteers with, he’ll think about the animals around him, even if they’re not in plain sight.

“The knowledge I’ve gained about species abundance and richness — it’s something I’ll think about going forward. When I see a rat scurrying around I’ll think ‘oh, that’s an urban exploiter,’” he says. “When I go upstate I’m going to be more aware of the animals I see on my travels.” ◆

Joshua Barber, of the EPA, worked with landscape designers to find wildlifefriendly mesh to use when remediating the Clearview Landfill Superfund site.

landscaping mesh can be a death trap for

Large landscaping projects, especially with increased local rainfall caused by climate change, require erosion-control planning. A search for products yields an array of mesh options designed to hold soil in place until plant roots can take over, but many can present an entanglement hazard to wildlife

The Philadelphia Metro Wildlife Center handles dozens of such cases during warmer months, says assistant director Michele Wellard. Mesh might hold soil in place, but if it doesn’t yield when a trapped animal struggles, it is deadly. At the center, Wellard has seen robins with legs that have been degloved (skin stripped off) and garter snakes with cuts too deep to heal.

After the removal of contaminated soil at

BY DAWN KANE

BY DAWN KANE

the former Clearview Landfill, part of an Environmental Protection Agency superfund site located between Darby Creek, Eastwick Park and the Clearview residential area of Philadelphia, workers covered much of the fresh soil at the 70-acre property with a thin mesh of woven jute to prevent erosion.

At home - improvement stores , plastic meshes are about half the cost of natural-fiber materials. But during the initial planning, Joshua Barber, the EPA scientist overseeing the Clearview project, was mindful that the site lies in a floodplain adjacent to the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge, so he worked with designers to find innovative materials for the job that would meet the EPA requirements for environmental stewardship.

The jute mesh protects plantings of oat,

rye, red fescue grasses and partridge pea plants that start growing within several days, Barber says. “So, if we need any kind of erosion control, we only really need a month for it.” He expects the natural mesh will last for about a year.

Along stream banks, where there’s higher erosion potential, a heavier woven coir coconut matting is rolled around soil and tree branches that will take root. The rolls are covered by soil and held in place by long oak stakes. “There are a lot of geese that walk over it, and they seem to do just fine,” Barber says.

As with any soil disturbance, the small mammals and birds are the first to return, Barber says. Perches have been installed among recently planted saplings since mice

and the voles will lure the raptors back.