REED MAGAZINE

From her thesis at Reed to the remote wilds of Alaska, bush pilot Lana Tollas ’19 has always found a way to take flight

ELECTIONS, POLITICS, AND (DIS)INFORMATION:

Election year 2024 is pivotal for the United States. Attend seminars and workshops featuring faculty and Reedies who are at the front lines of elections and political processes in an age of information overload and disinformation.

REUNIONS 2024 | JUNE 6–9

ALUMNI COLLEGE | JUNE 5–6 reunions.reed.edu

Join your fellow alumni on campus for a spectacular weekend full of traditions, class revelry, and more. Plus—if your class year ends in a 4 or 9, you have a quinquennial anniversary to celebrate!

Spring 2024 Volume 103, No. 1

EDITOR

Katie Pelletier ’03

ART DIRECTOR

Tom Humphrey

WRITER/EDITOR

Britany Robinson

CLASS NOTES EDITOR

Joanne Hossack ’82

REEDIANA EDITOR

Robin Tovey ’97

GRAMMATICAL KAPELLMEISTER

Virginia O. Hancock ’62

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Lauren Rennan

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS AND COMMUNICATIONS

Sheena McFarland

Reed College is an institution of higher education in the liberal arts and sciences devoted to the intrinsic value of intellectual pursuit and governed by the highest standards of scholarly practice, critical thought, and creativity.

Reed Magazine provides news of interest to the Reed community. Views expressed in the magazine belong to their authors and do not necessarily represent officers, trustees, faculty, alumni, students, administrators, or anyone else at Reed.

Reed Magazine (ISSN 08958564) is published quarterly by the Office of Public Affairs at Reed College. Periodicals postage paid at Portland, Oregon.

Postmaster:

Reed Magazine

3203 SE Woodstock Blvd. Portland, Oregon 97202-8138

503-777-7591

reed.magazine@reed.edu www.reed.edu/reed-magazine

I didn’t know much about the history of calligraphy at Reed when I was a student in the early aughts, though its legacy still swirled around. I’d heard something about there having once been classes and world-class calligraphers here. And there was beautiful lettering in frames and cases in the library that I often paused to look at during the long hours I spent there. But it wasn’t until I came back to Reed as a staff member that I really noticed it everywhere—in flyers, exhibitions, Reunions themes, Paideia classes, and the steady archival use of Lloyd Reynolds’s [English and art 1929–69] papers. The Calligraphy Initiative at the Douglas F. Cooley Memorial Art Gallery—the brainchild of Stephanie Snyder ’91—had revived the practice on campus in 2012. Students and alumni were attending weekly scriptoria, adorning the campus trees with weathergrams, and in all the years I’ve been here, I don’t think that an issue of Reed Magazine has gone to press without a mention of calligraphy or Lloyd Reynolds somewhere within.

What had seemed to me to be a dusty tradition when I was a student was in fact quite alive.

When we were taking a close look at our nameplate for the magazine during the redesign process, sorting through fonts and styles, we saw a great opportunity to draw on this heritage. Our design team reached out to Gregory MacNaughton ’89, coordinator of education, engagement, and the Calligraphy Initiative, and asked him to collaborate with us on lettering. Generously, he did, penning the distinctive capital R that we are proud to share on the cover of our newly redesigned magazine. This collaboration and resulting nameplate honor not just Reed’s calligraphic heritage, but all the meaningful threads that run through Reed’s history and tie together its community.

Thank you to all of you who filled out our survey, made comments, or took the time to write an email during our redesign. Your feedback was thoughtful, heartening, and crucial. Based on what we learned, we plan to focus the coming issues on material that speaks to the interests and preoccupations you shared with us. We want to tell authentic stories of alumni and students solving problems in their own lives and in the world. We want to illuminate the impacts that Reed and Reedies are having locally and globally, in small and large ways. And, we want to dig into the big issues with Reed thought leaders: faculty, alumni, and students who are applying their minds to rigorously question, test, investigate, solve, find meaning, and contribute important knowledge to the world. To me, these capacities are the strongest thread that unites all Reedies.

—Katie Pelletier ’03, Editor

—Katie Pelletier ’03, Editor

14

President Bilger sits down with Dean of the Faculty Kathy Oleson and Vice President and Dean of Intitutional Diversity Phyllis Esposito.

BySheena MacFarland

16

On the path to professional fulfillment, sometimes we need a big change.

By Britany Robinson

24

From her thesis at Reed to the remote wilds of Alaska, bush pilot Lana Tollas ’19 has always found a way to take flight.

By Chris Santella32

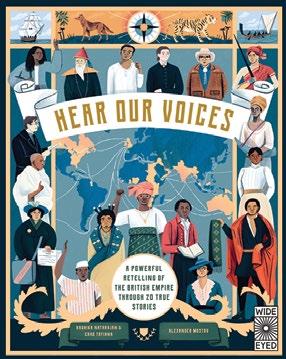

Stories of British colonialism come to life in Prof. Natarajan’s Hear Our Voices.

By Laura Atkins

I just watched the film Riders on the Storm in the article “Changing the Lens” [December 2022]. Wow, it takes something we see every day, but are blind to, and makes it compelling. Homelessness through the eyes of a young adult. I rolled my eyes when I read the introduction. By the end of the film, my eyes were wide open.

BRUCE ANTELMAN ’79NEW YORK, NY

I received the latest issue and noticed there wasn’t a Letters to the Editor feature. I enjoy “hearing” alumni voices and the details that we get hung up on. Where did it go?

TRACY WEBER ’95

PORTLAND, OREGON

Editor response: The letters to the editor section is one of my first stops when reading any magazine, but we have been getting fewer and fewer. Please write!

When I first began receiving Reed Magazine, alumni listed in the class notes under “Class of ’23” were vigorous octogenarians. These people had enjoyed cocktails with F. Scott and Zelda and woken up to the long hangover of the Great Depression. They recovered in time to eat fascists for lunch, then spent a long summer

afternoon building a postwar juggernaut. In the early evening they had to decide whether to shoo the hippies off their lawns, or bring lemonade to their tents. I was honored to meet a few of them at a soiree. Amazing people.

Now the “Class of ’23” is full of equally amazing people, dauntlessly facing the challenge of saving our planet from the mess left by the first Class of ’23 and the rest of us since.

My question is, is it time for our Class Notes to list class years in four digits? Maybe not. I am finding the realization that the life cycle of institutions exceeds that of individuals to be poignant, just now.

ALEX LEVINE ’88 TAMPA, FLORIDAMy heart broke learning of the death of Jeremy Stone ’99 [March 2023]. We served together on the alumni board, and Jeremy was instrumental in transforming the Reed Career Alliance. His sharp mind and quick wit always made the work more enjoyable.

I will miss Jeremy’s unrestrained giggle (if you ever heard it you know what I’m talking about), his unique ways of building community (often bacon based), and his joy, pride, and love when speaking of his daughter Ellie.

KRISTEN M. EARL ‘05 PORTLAND, OREGON

In October, students, staff, and faculty added nearly 100 native plants to a prairie restoration site on Reed’s campus. Camas prairies once blanketed much of the Willamette Valley, and the bulb of the plant was an important food source for Indigenous inhabitants of the region. Today, just a tiny fraction of those prairies remains. The event was put on by Reed Camas Prairies, which educates about the cultural significance of camas, tribal food sovereignty, and restoration efforts. The project, launched last summer with funding from the Social Justice Research and Education Fund in partnership with Science Outreach, will offer future opportunities to care for the plants through their first year.

PHOTO BY TOM HUMPHREY

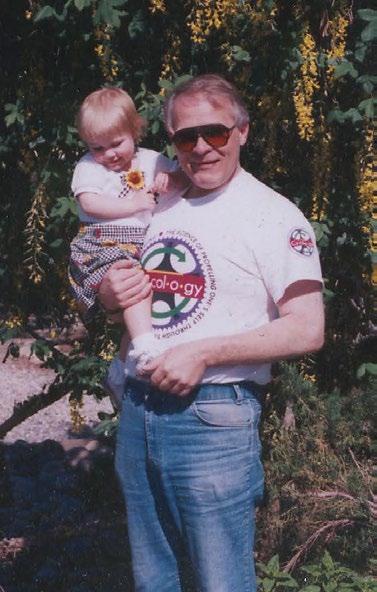

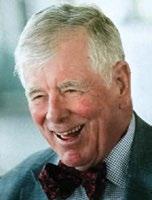

After 26 years of leadership, Hugh Porter departs.

When he arrived at Reed, Hugh Porter noticed that when asked what was distinctive about Reed, alumni sometimes pointed first to the social culture.

This was not the way he saw it.

“What really is distinctive about Reed is the way the academic program is arranged: with dedicated faculty and a curriculum that is a steep climb rather than a downward slope of intensity,” he says. He wanted alumni to more deeply appreciate Reed’s intellectual impact, and to celebrate and support the college’s remarkable academic strengths.

Porter, now Vice President for College Relations and Planning, has spent 26 years dedicated to finding innovative ways to further Reed’s mission and secure its longevity. His success has led to numerous advancements in the breadth and depth of Reed’s

academic program, substantial increases in student financial aid, and critical funding for changes to the built environment. He also planned and spearheaded the largest fundraising effort in Reed’s history, which concluded in 2012 with more than $203 million raised.

“Hugh has had the incredible capacity to dive in, care, and support out-of-the box solutions,” says Trustee Jane Buchan. “He is a true Reedie in terms of dealing with the ‘what’ and looking behind issues for productive solutions.”

In addition to being responsible for the college’s fundraising, Porter oversees advancement, alumni relations and volunteer engagement, communications and public affairs, conference and events planning, institutional research, and the Center for Life Beyond Reed.

From 2018 to 2019, he served as interim president and helped recruit a new president. In this role he was especially buoyed by interactions

with students, who are—as he frequently reminds colleagues—“the reason we’re here.” When a group of students organized a Renn Fayre softball team called Hughes on First, he naturally joined in. Due to the no-strike limit, he was able to engage in long conversations with students on the field—often while waiting at first base, of course.

In 2019, Porter took over the responsibility of institutional planning, and during the pandemic, served as cochair of the COVID19 Risk Assessment Group, working tirelessly to ensure the safety of all on campus.

Porter holds a bachelor’s and master’s degree in music history from Yale University. He is an accomplished cellist, and, in his post-Reed life, plans to apply his skills to collaboration and challenges of a different sort, like ensemble music performance— which is a very Reed thing to do.

—Katie Pelletier ’03Porter has served under Presidents:

Steven Koblik [1992–2001]

Peter Steinberger [2001–02]

Colin Diver [2002–12]

John Kroger [2012–18]

Audrey Bilger [2019–]

“Hugh has been a trusted colleague and valued member of my leadership team. I have personally benefited greatly from his wisdom, grace, depth of institutional knowledge, and friendship.” —President Audrey Bilger.

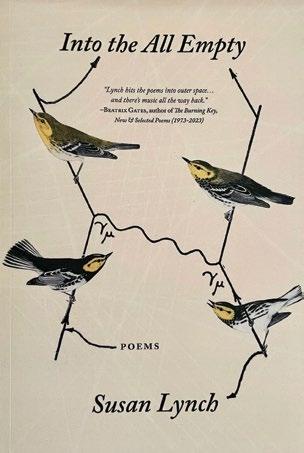

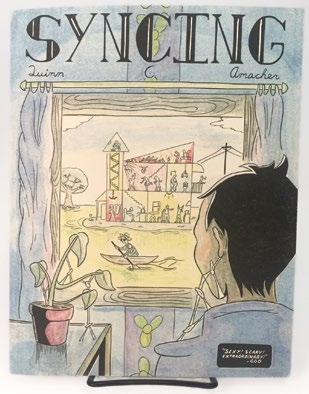

The risograph is not a cool-looking machine. It’s big and blocky and gray, calling to mind an office copier. Indeed: invented in Japan in 1958 for office use, it fell out of favor as the photocopier rose. But what the risograph makes? That’s very cool. With rice bran inks that verge on fluorescent and a process that’s precise yet unpredictable—essentially a cross between stencil duplication and screen printing—the risograph has seen a surge in popularity in recent years among artists, zine makers, independent publishers, and designers, all drawn to the way the machine pairs a DIY aesthetic with automated efficiency.

“It’s a collaborative process between you and the machine.”—Charlotte Applebaum ’27

Now Reed has its own risograph. Visual Resources Curator Chloe Van Stralendorff proposed the acquisition last year, and the risograph arrived in June. Van Stralendorff, who runs the Visual Resources Center (VRC), wanted an outlet for students that would be creative and experimental as well as practical.

“I just knew we needed one,” she says. “Reed has this interest in zines, in comic books, in DIY posters. The risograph seemed like the right fit, and I felt students would respond to it really well.”

She was right. Student visits to the VRC multiplied over ten-fold. Van Stralendorff also partnered with Ann Matsushima Chiu, social sciences librarian and curator of the Reed Zine Library, to offer two risograph workshops led by Portland artist Timme Lu. At the first, held in November, a dozen students created collaborative collages and then inked them into vibrant pieces of art. Lu will return for another workshop in March—just a few days before the first Reed Zine Fest, a library-organized celebration of zines and other indie publications. Van Stralendorff collaborated with studio art faculty to incorporate the risograph into coursework, too. In the fall, students in Art Professor Daniel Duford’s Making Graphic Novels class and Professor Michael Stevenson Jr.’s Drawing in Many Forms class all undertook risograph work. “It’s a collaborative process between you and the machine,” says Charlotte Applebaum ’27, likening it to the experience of placing an unfired piece of pottery into a kiln. For each new color of ink the paper needs to be reloaded, which means the layers don’t line up perfectly. According to Stevenson, surrender is part of the lesson.

—Rebecca Jacobson

it—a miniature plane, that is. The impact from the yellow model Piper Cub left no mark on the cross-laminated timber beam it hit this fall. The plane and its remote aviator have yet to be reunited, however.

In its annual contest, Helium Comedy Club named sophomore Cameron Peloso ’26 Portland’s funniest person. He was the contest’s first Gen Z winner.

The Quest received a best of show award for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Reporting at the 2023 National College Media Conference in Atlanta.

Reed is home to the only nuclear reactor in the country staffed by undergraduates, a distinction highlighted in a recent episode of the Atlas Obscura podcast.

PHOTO BY CORNEILA SOMA PENN ’24

PHOTO BY CORNEILA SOMA PENN ’24

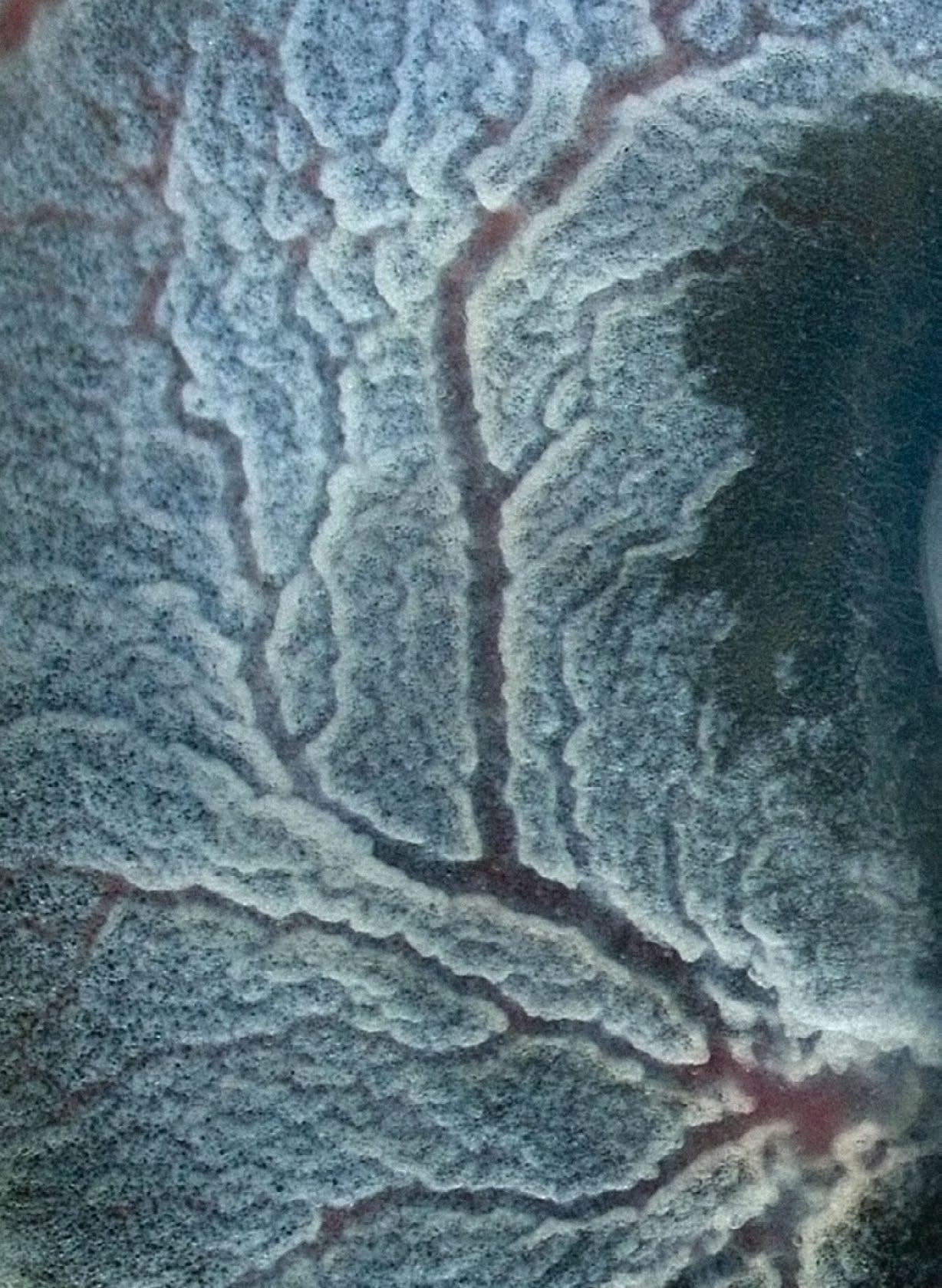

Winning photo from annual Developmental Biology Image Contest sheds light on development and survival.

The embryo in this image belongs to a chicken strain known as an Easter Egger for the blue-and-green color of its eggs. To observe a chicken embryo, you must first crack the egg into a salt solution, remove the albumen—what we would call an egg white—and carefully peel the embryo away from the yolk.

The image was taken by mounting the embryo on the stage of a dissecting microscope, then holding a smartphone over one of the eyepieces. No longer concealed by its shell, the embryo’s heart visibly beats, pumping blood, with its head and brain oriented toward the top, and the heart tucked under its head. The membrane and blood vessels that circle the embryo provide nutrients and oxygen to support development and remove metabolic waste. In my Developmental Biology (biology 351L) lab, we study the genetic, chemical, and physical forces that influence embryo formation. This one is surprisingly resilient: as long as it is kept hydrated, covered with egg albumen, and supplied with a calcium source, it can carry on developing. The heart will continue to beat.

—Kaya Green ’25

Foundation to fund Prof. Nicole James’s research on chemistry

Chemistry education researcher and materials chemist Prof. Nicole James [chemistry] has won a grant from the National Science Foundation’s Building Capacity in STEM Education Research. She will receive $340,808 to research best practices in science education. The funding will support her project “BCSER: Identifying the Foundational Concepts and Skills of Materials Chemistry,” which will provide insights to help educa -

tors support STEM students in interdisciplinary endeavors.

James knows from experience that contemporary science curriculum often fails to meet the needs of students who hope to pursue interdisciplinary work, whether it takes the shape of materials chemistry, environmental chemistry, or another field of study. Introductory courses cannot cover all of these subdisciplines, which means educators often face the choice between

prioritizing either breadth or depth when planning first-and second-year chemistry courses.

“Sometimes if we teach more, they learn less,” James says. This dynamic, she says, is partly due to historic approaches to science curriculum that date from the 1950s. Even if schools want to upend these curricular norms, change comes with its own complications, including difficulties for students seeking to transfer or pursue exchange programs.

So if they want to recruit students to pursue and thrive in interdisciplinary fields, what’s a science educator to do? “If I have one week to present a case study, which is it going to be?” James says. That is: Which scientific skills and concepts are most widely used in interdisciplinary chemistry work? How can those topics be taught in a way that helps young scientists take what they know and apply it in a context they’ve never seen before?

The grant-funded project will explore these questions through interviewing chemistry postdocs about the concepts and skills they use in their work. James will also devise, execute, and analyze a national survey. Throughout all of this, Reed students will have a role to play: they are contributing to the theoretical faming of the study, interview collection and analysis an more—perhaps with an end result that benefits future students like them. —Katie

Pelletier ’03

Anthropology students excavate on Reed’s campus in search of its lost history.

Sifting through layers of soil in the canyon, students aimed to learn more about earlier use of the land where Reed now sits. The students were taking Prof. Alejandra Roche Recinos ’s Anthropology 311: Archaeology of Reed this fall, where they were introduced to the hands-on work of archaeology: surveying, mapping, documentation, excavation, artifact identification, and artifact interpretation.

It wasn’t all dirty work, however. The course focuses on familiarizing students with the steps that happen before and after the dig, as well as the legal, ethical, and logistical requirements of fieldwork. They honed skills communicating with stakeholders and invested institutions.

They visited the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Historic Preservation Office and the Oregon Historical Society, and through this research they learned that the spot where they’d proposed to excavate had once been the site of a house that was demolished when Crystal Springs Farm was donated to Reed. “One of the inhabitants of the house was actually a Reed alum from the 1950s.” said Prof. Roche Recinos. “Our developing research questions focus on finding more out about this house, its inhabitants, and their relationship to Reed.”

This fall, their efforts yielded some gardening-related materials, construction materials, lots of plastic, and part of a squirrel jaw.

“All of this seems to date within the past 20 years, and we’ll see what we recover next semester!” said Roche Recinos. —Katie Pelletier ’03

Prof. Alexei Ditter [Chinese] spent six months in Taiwan on a Fulbright Scholar grant. Here he shares a glimpse of his time there—on a trip to Lukang, a hub of culture and history.

When my Taijiquan (tai chi) teacher, Serge Dreyer, offered to play tour guide on a visit to Lukang 鹿港, a small town on the west coast of Taiwan, I jumped at the opportunity. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Lukang had been an important center for trade and one of Taiwan’s largest cities. Today it is best known for its preservation of historical buildings and a flourishing culture of local religions. One place where these intersect is in the

use of talismans (fulu 符籙). These appear in both private spaces (above entranceways to homes) and public ones (on light posts, telephone poles, or exterior walls), and are used to protect people from evil. When multiple talismans appear in close proximity to one another, they suggest that an accident or death occurred at that location.

At Lukang’s famous Mazu Temple, we encountered a religious procession composed of multiple groups, each representing a different folk deity. Each group would escort its deity into the temple courtyard and have a performance. These involved chanting and music; in one, four Nezha danced together to Korean pop songs.

—Professor Alexei Ditter

FIND THESE STORIES AT: reed.edu/reed-magazine

“It is one thing to be passionate, but how you decide to articulate that and show up makes a difference,” said Trustee Emerita Adrienne Nelson. She and two other Reedie Oregon Supreme Court justices, Bronson James ’94 and Christopher Garrett ’96, told Reedies about their paths to becoming judges in a panel organized by the Reed Legal Network. By Amanda Waldroupe ’07

Meet Reed’s new trustees: Susan J. Sokol Blosser MAT ’67, Larry Abramson ’80, and Tina Sohaili-Korbonits ’07 joined the board earlier this year. Each brings unique experience and expertise to the board.

Paideia 2024: Despite the snowand ice-covered roads, students, staff, and alumni were still able to come together for this year’s celebration of learning. Instructors led classes from as far away as Croatia and as close as a few hundred (slippery) feet from their dorms. Check out what we learned. By Faolan Cadiz ’25

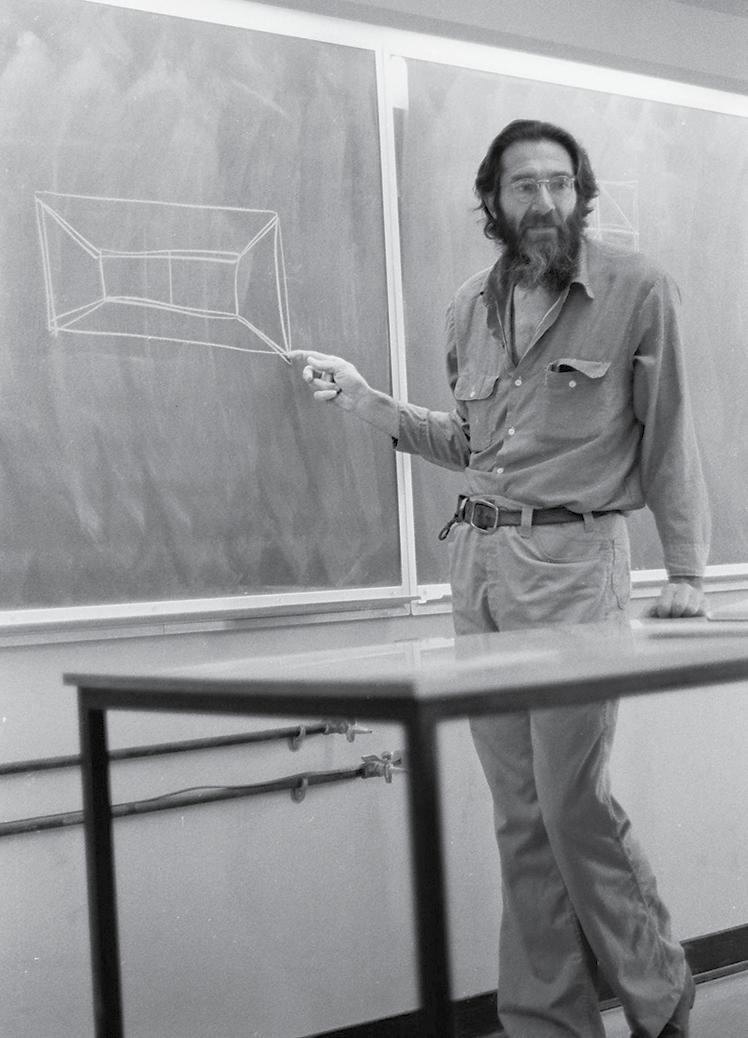

In a recent interview, the late Prof. Nicholas Wheeler ’55 [physics 1963–2010] recounted to the Lake Oswego Review giving J. Robert Oppenheimer a tour of Reed’s campus. [See also In Memoriam.]

The Los Angeles Times published a letter by Sharon Toji ’58 on the subject of the liberal arts education. “I’m 87, still working, and proof of the value of college humanities,” said the pioneer of accessible signage in the U.S.

“We thought it would be fun to own a bar,” says Jason Marks ’84. If you stop by Juno Brewery in Albuquerque, New Mexico, the fun part will be evident. You might come in for a hopping happy hour or be lured in by the sound of live Latin music and join a salsa lesson. You’ll almost certainly spot the owners, Jason and his wife, Maxine, who are frequently pouring pints or serving food themselves. Jason says this retirement project has been fun—but it’s also “a huge amount of

work.” When he decided to open a brewery in 2021, he imagined himself sitting in the corner with his friends, watching customers come and go. The “retirement” endeavor has been much more hands-on. The work is hard, but as a result, Juno Brewery has become a local favorite.

Jason studied sociology at Reed before getting his law degree at the University of New Mexico. He practiced law for nearly two decades. When it came time to retire, he struggled with the idea of not working. He says the brewery has made it possible to “retire,” because he gets to keep working, but on a hobby he really loves.

He partnered with experienced brewers to devise the recipes that come together in large fermentation tanks, visible from the bar. “We do the basics well,” he says. But to fully appreciate Juno’s beer, you really need to be in their space.

“We have a family-run vibe,” says Jason of the high-ceilinged, airy brewpub. Their focus on fostering community here has brought in local artists to feature work on the walls and gallery, and meetups for various groups, including Reedies and the Sierra Club. Outside there’s a large patio, a popular destination in the summer months.

Jason and his wife enjoyed dancing

REUNIONS: June 6–9

Relish all that you love about Reed(ies) during Reunions weekend. Join your fellow alumni on campus for a spectacular weekend full of traditions, class revelry, and more.

ALUMNI COLLEGE: June 5–6

Elections, Politics, and (Dis)Information Election year 2024 is pivotal for the United States. Its long process will dominate the media and have profound implications for the country’s future. Attend seminars and workshops led by faculty and Reedies who are at the front lines of political processes in an age of information overload.

Come to one. Come to both. For more information see reunions.reed.edu.

ALUMNI CHAPTERS

Want to connect with Reedies in your area? Reedies can share their joys and passions with each other through creative events and fun gatherings.

REED CAREER ALLIANCE

prior to opening Juno. But in opening their space to Latin dance nights, they’ve embraced the art form. It’s an activity that customers are really excited about, and the owners love it, too.

At Juno, Jason’s interests in beer and building community have blossomed into a space where people—including the owners—can explore something unexpected. “There’s a very Reed spirit in forging ahead into new, completely different things,” he says. —Britany Robinson

To find more Reed breweries, or other Reedie businesses, or to register your own, see iris.reed.edu/directory/reedie_businesses.

Support fellow alums in developing careers through virtual and in-person events, professional and affinity networks, peer mentoring, and other alumni-led initiatives. Reed alumni may well be other Reedies’ secret weapon in navigating the working world.

COMMITTEE FOR YOUNG ALUMNI

The Committee for Young Alumni (CYA) helps young alumni connect, continue their intellectual journey, and collaborate in their post-Reed lives in meaningful and relevant ways. Consider joining the committee if you graduated from Reed fewer than 10 years ago.

For more information about any of these opportunities, please call alumni relations at 503-777-7589 or email alumni@reed.edu.

Deep intellectual curiosity. A voracious appetite for learning. Multidimensionality. These are all aspects of the Reed College experience that connect students and alumni across time. And as Reedies continue to change, so too does Reed College. As the college works to be ever more inclusive and welcome students from a variety of backgrounds and lived experiences, Reed continues to evolve to create an experience that is accessible to every student accepted to the school.

To do that, Reed has centered inclusive excellence as the driving force behind its mission.

“Reed College has always been on the leading edge of academic excellence, and inclusive excellence is a defining feature of academic excellence,” said Reed College President Audrey Bilger

She recently sat down with Phyllis Esposito, vice president and dean for institutional diversity, and Kathy Oleson, dean of the faculty and professor of psychology, to discuss inclusive excellence and its importance at Reed College.

Esposito pointed out that schools typically take one of three

approaches to diversity, equity, and inclusion on their campuses: embracing a multicultural perspective, tallying diversity through numbers, or inclusive excellence. Reed has chosen to take the inclusive excellence approach because it is a practice informed by theory that connects to and reflects Reed’s institutional mission.

Education researchers Damon A. Williams, Joseph B. Berger, and Shederick A. McClendon define inclusive excellence as the “strategic pursuit of balanced diversity objectives, repositioning diversity and inclusion as crucial to institutional excellence and quality.” Inclusive excellence has been at the heart of Reed’s strategic planning and academic pursuits for the past several years.

Reed continues to become a more diverse place, opening access to a wider variety of students from more backgrounds than ever before. The richness that comes from such diversity creates community cultural wealth. Bringing in new perspectives, ideas, and attitudes makes for a greater intellectual feast because of the more varied flavors of the ingredients.

“For anyone who might imagine that there’s some tension between rigor and inclusivity and diversity, we know that is not the case,” Bilger said. “In fact, the best pedagogy is inclusive pedagogy. The best campus is an inclusive campus.”

Oleson agreed, pointing to the Center for Teaching and Learning, which was established in

2014 and reports to the Office for Institutional Diversity. That center was purposely designed to support faculty in taking a more inclusive approach to their teaching—in learning new ways to ensure that students are thriving in their classrooms, and that their curricula highlight the breadth of knowledge that exists across cultures.

“Excellence has always been at the core of Reed’s mission,” Oleson said. “And to be truly excellent, we need to be inclusive.”

Excellence can sound like a destination, but it’s actually a process that requires scaffolding to allow everyone to build toward that goal together.

“The reason that this becomes a framework, and not a set of slogans, is because we believe it’s integral to what makes the college amazing, and what will continue to allow the college to thrive in this century,” Bilger said.

Esposito agrees that it is essential to take a scaffolded and evidence-based approach to inclusive excellence for it to continue to be at the heart of the work Reed does. That means being able to adapt to an ever-changing world.

“Context matters, and situation matters. We can be nimble in that we will be present with the students that we receive in the context in which we find ourselves,” Esposito said.

Inclusive excellence serves as a launching point for further work and continuous improvement. It is important to gather both quantita-

tive and qualitative data and then to embrace evidence-based practices.

That can then lead to a continuous improvement process that allows Reed to identify key priorities that can lead the campus community to the creation of specific goals.

The campus community came together to create Reed’s powerful, aspirational diversity and antiracism statements (written in 2009 and 2017, respectively). Continuing to move those statements from an idea to a practical reality is the

path Reed has been walking, and the next steps emphasize even more the need for further strategy and actions.

Bilger acknowledged that the statements are something Reed has embraced, and that it is important to continue turning those highlevel statements into practical work and to start to measure outcomes.

“These are more than just words, they’re commitments. And commitments require action and strategy and planning,” Bilger said.

Part of that commitment has come and will come from alumni, who through their advocacy, volunteerism, and engagement with the college can assist in creating a welcoming environment for students.

“Alumni have contributed and will further strengthen our mission of inclusive excellence by believing in the best for this college and believing in the ongoing evolution of Reed in the 21st century to meet the needs of today’s students,” Bilger said.

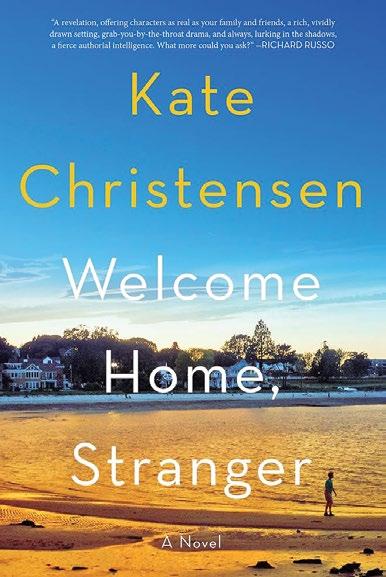

On the path to professional fulfillment, sometimes we need a big change.By Britany Robinson Illustrations by Melinda Josie

“It doesn’t seem like you’re passionate about this work.”

Aaron Good ’01 was taken aback. No, he was not passionate about managing a server infrastructure to push videos of sneakers to iPads in retail stores. Who would be? He was capable and he worked hard. But the person interviewing him for a new position at Nike, where he’d already been employed for 13 years, was right. He was not passionate about his work.

In that moment, he realized he wanted to be.

The term “The Great Resignation,” was coined to describe the wave of workers who quit their jobs or were looking for new ones in 2021. After the collective trauma of millions of deaths, the closure of countless small businesses, the resignation of so many parents (moms, mostly) from the

workforce to care for their kids, and innumerable impacts that continue today, a shadow was cast over how and why we work. The answer, for many, was to go searching for something new.

As quarantines lifted and business slowly returned to normal, 41% of the workforce was considering leaving their current employer, according to Microsoft’s Work Trend Index report for 2021. Of those considering changes, 46% planned to make “a major pivot or career transition.”

Things have settled down a bit since then—as far as the job market is concerned. But there will always be people looking for something new—something better—when it comes to work. According to a 2023 survey of 2,500 U.S. workers, one in four was looking for a new job. While a majority will

stick to jobs in the same field, changing careers completely isn’t uncommon; 29% of workers will change fields at some point after college.

The allure of shedding your title— your identity, even—for a new endeavor didn’t start with the pandemic. There have always been people who break away from the straightline career trajectory for a greater purpose, passion, or paycheck. And there are those who are forced to do so, as a result of new technologies, layoffs, and all sorts of industry-specific crises.

In the late 19th century, for example, if you were a knocker-upper (someone hired to knock or throw something at windows to wake the inhabitants for work), you would have soon found your job made obsolete by the invention of the mechanical

alarm clock. Today, if you’re a journalist, then you’re attuned to a steady stream of layoffs and the folding of so many publications.

Artificial intelligence is today’s career saboteur. According to 2023 data from Challenger, Gray & Christmas, AI replaced nearly 4,000 jobs in just May.

Losing a job ranks as one of life’s most stressful moments, alongside death and divorce. It can also, in the right circumstances, present opportunity.

“Getting fired from Apple was the best thing that could have ever happened to me,” Steve Jobs ’76 told the graduating class of Stanford University in 2005. “The heaviness of being successful was replaced by the lightness of being a beginner again. It freed me to enter one of the most creative periods of my life.”

That’s easy to say when you’re a billionaire. For others, the “lightness of being a beginner” is often heavy with student debt and time away from loved ones to earn a new degree or start a business.

And yet, so many find it’s worth it.

The weekend after Aaron’s interview, he went to a coffee shop with a notebook and made a list of the things he did care about, narrowing them down to mental health, housing, hunger, literacy, and the environment.

Surrounded by the hum of coffee shop conversation, Aaron committed himself

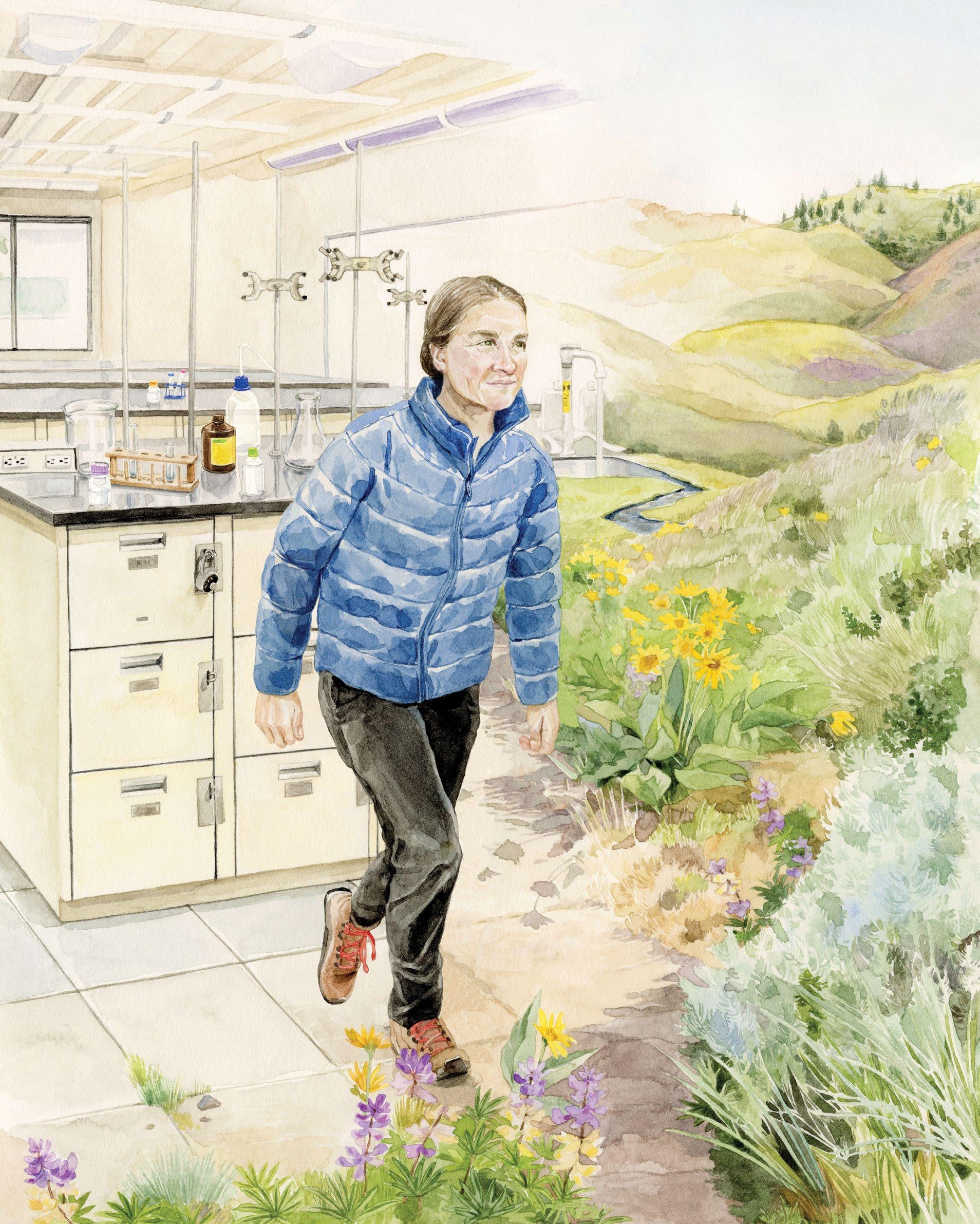

Sarah Kliegman ’02 majored in biochemistry and molecular biology, becoming a researcher and faculty at liberal arts colleges, including Reed. But she yearned to be closer to the issues she studied.

calls from people in crisis each shift, he thought, Well, if I can handle this, I can handle being a mental health counselor.

Aaron found the work of helping individuals immensely rewarding, so he applied to graduate school at Portland State University, where he specialized in clinical rehabilitation counseling. He completed his first year while he was still working fulltime. In the sum-

Sarah, like the wildflowers, was still part of this community, and it was being polluted by a greedy corporation. She felt called to join the effort to hold those companies accountable, and to make sure they cleaned up the damage.

to pursuing work in one of these areas.

Before leaving Nike, he tested the waters of various career options through volunteer opportunities, first by wading into the literal water of the Sandy River delta, where he trained to lead riparian restoration teams. He also started packing food at the Oregon Food Bank, cleaning books at Oregon Children’s Book Bank, and building houses with Habitat for Humanity. Lastly, he started working at a suicide crisis line. After doing that work for a while, answering 4 to 15

mer before his second, Aaron was riding shotgun when the driver of their vehicle fell asleep; Aaron grabbed the wheel just before they careened off a winding road. Surviving what he’s sure would have been a fatal car crash, Aaron decided it was time to go all in, to quit his job and focus on school.

Today, he’s a therapist providing mental health and career counseling in Portland. About 65% of the clients he meets for career counseling are mid-career and looking to make a big change.

“It’s a process that starts with a simmering dissatisfaction,” writes Herminia Ibarra, author of Working Identity Ibarra argues that people living and working today will face accelerated technological change and more working years, which result in a more circuitous path than the straight line to retirement followed by past generations. We have more time, and more reasons, to change our minds.

That “simmering dissatisfaction” can be the energy that pushes one to reassess, to explore new options, to return to the thing you’ve always known you loved. That simmering can also feel like fear or uncertainty, like losing control, a feeling that might force you to take the wheel and change directions.

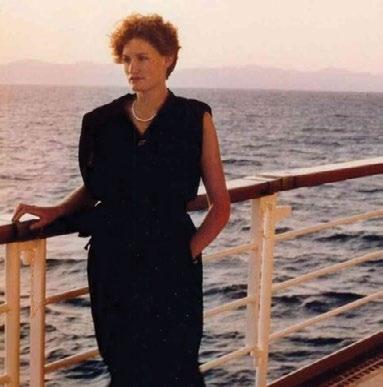

Sarah Kliegman ’02, at 10 years old, knew the pristine alpine lake was a lie. She was sitting next to her parents in a gymnasium filled with neighbors and community members. At the front of the room, Battle Mountain Gold Company was telling the residents of Okanogan County, Washington, that if they were allowed to develop a large-scale, openpit gold mine, there would eventually be an alipine lake at the top of Buckhorn

Mountain. But Sarah had seen pictures of Butte, Montana, where a mine similar to the one being proposed left behind a pit full of water so acidic that to this day, it kills birds that land on its surface. “I knew Butte was like, one of the most polluted places in the country.”

The town was split, with many people standing fervently against the mine while others were excited by the promise of new jobs and a boost to the local economy.

Those opposed, who included Sarah's parents, spent the following years untangling a web of fine print, combing through massive environmental impact statements to find and expose all the ways in which the mine could hurt their town. The Okanogan Highlands Alliance (OHA) formed to organize the opposition.

Sarah was studying at Reed when the courts finally ruled against the mining company, citing the likelihood of massive environmental damage. Having seen the disruption caused by the proposal for so many years—how it forced so many working-class folks in the region to sacrifice their time and energy in fighting one of the largest gold mining operations in the country—Sarah wanted to help in her own way. She was majoring in biochemistry and molecular biology at Reed, to better understand the science behind mining’s impact on surrounding ecosystems.

She was especially interested in remediating mine pollution. Prof. Arthur Glasfeld [chemistry 1989–2022], her thesis advisor, suggested she focus on metal-dependent DNA-binding proteins, which are important factors in this process. Upon graduating, she felt as though she’d barely scratched the surface of this topic, but she was hooked on the science—the process of understanding, at a molecular level, what was happening to the environment.

After graduating, she got a job doing biochemistry at OHSU. The work there was not related to metals or mining. And she quickly realized something about herself.

“I was willing to struggle and fail when it was something I really cared about,” she says. “But when it was a

subject I didn’t have a personal connection to, I was a lot less willing.”

Sarah stuck with it. After earning her PhD at the University of Minnesota— where she did get to focus on how metals could help degrade pollution in groundwater—Kliegman taught as a visiting professor of chemistry at Reed from 2014 to 2016, then at Claremont McKenna Colleges.

Teaching brought her a little closer to the reasons she cared so much about science. She loved sharing her passion with students, especially when she was able to connect the lessons to important environmental issues, like the water crisis in Flint, Michigan. But she was often frustrated by the distance between studying science and protecting precious places by using science.

“I needed to have my hands in the dirt,” she recalls.

Sarah visited Tonasket in the summer of 2017, the time of year when the pine trees smell of butterscotch. She says not many people love this little corner of the world. But she does. When asked why, she pauses and takes a deep breath. Sarah’s words turn poetic when she talks about home.

“I love it for the way the little creeks dance off the mountains; for the way the light filters into those shady, mossy places along the creeks; for each of the characters from the plants to the pollinators in the riotous wildflower meadows and the unique role each of them plays in their community.”

Sarah hadn’t lived in Tonasket since 1998. Now, she learned, there might be a really good reason to come back.

At this point, her father had been serving as executive director of OHA for 25 years. He wanted to retire soon. But there was still important work to be done.

Back in 2000, a grassroots effort had stopped the gold mine from moving forward. But just two years later, corporate mining interests renewed their efforts to develop a mine in the heart of the Okanogan Highlands. OHA again worked tirelessly to fend them off, but eventually the difficult decision was made to settle with the company, and an underground mine

MAJOR Anthropology

CAREERS

It was the late ’90s, Y2K. They thought the grid was going to go down, and there was a huge push to retrofit aging computer systems. That’s how I started doing recruiting work. I did it for over 10 years. It was good money, so it was hard to walk away. But I worked all the time and got really burned out. I was about 40 at the time, and a triathlete. I was keenly interested in how physical movement and exercise affect quality of life. I woke up one morning and thought, I could become a chiropractor! I knew I would take a financial hit, but there’s more to life than money. I started grad school in 2013, at 43.

Reed trains you well for difficult academic experiences. While grad school was challenging, being away from my kids (aged 10 and 13) was the hardest part. They stayed in Ashland; I was in Portland. I commuted back and forth every other weekend. I saw them as much as I could, but I really missed them.

I’ve now been working as a chiropractor professionally for eight years. My greatest joy is improving my patients’ ability to return to doing what they love. When treatments have an instantaneous effect, it’s very rewarding. People will be in tears, they’re so grateful.

was developed. Operations began in 2008, but the robust protections they’d agreed to proved futile. Water monitoring revealed problems almost immediately, and violations worsened for years. The mine released sulfate, chloride, and nitrate, as well as arsenic and metals like copper, zinc, and manganese, polluting the local groundwater. It stopped operating in 2017, but destructive water violations continue today.

Sarah, like the wildflowers, was still part of this community, and it was being polluted by a greedy corporation. She felt called to join the effort to hold those companies accountable, and to make sure they cleaned up the damage.

“That water runs in my blood,” she says.

When it came time for Sarah’s father to retire, she could take his place at OHA, and continue that work.

She asked herself, could she leave her teaching job to head up a nonprofit, sacrificing the financial security of a career she'd been building for years?

“It’s too late!” she told a friend. “I’ve invested too much time in becoming a researcher and an academic.”

Her friend didn’t hesitate to respond: “It’s never too late.”

Sarah considered the option for two years. When she thought about leaving academia, she thought about what she enjoyed most about teaching. She loved helping students make connections between fundamental chemistry concepts and real-world environmental issues like climate change. As a final lecture of the semester at Claremont, she dove into the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, connecting everything they’d learned about oxidation, reduction, and acid-base chemistry to the real-world tragedy of a community without clean drinking water. But that was just a handful of lectures. “I felt like I was 20 steps away,” she says, of the issues she felt were most urgent. “And I wanted to be one or two.” She now had the opportunity to step directly into what she cared about most.

After the birth of her child, Sarah felt ready to return to the Okanogan Highlands. She accepted a position as co–executive director, an arrangement that allowed for a healthy work-life

balance for both Sarah and her counterpart. It was a chance to be part of building a strong community, to prioritize clean drinking water and a healthy environment for generations to come. It felt right. It felt like home.

Leah Lockwood ’92 was working as a paralegal when she bought her first home at 25. She knew it would be a long journey to see its full potential. Purchased for just $50,000, the house needed major renovations. Leah didn’t know much about houses at the time, but

“I thought I could do anything. That’s what you think when you’re young.”

as a young, recent graduate with a degree in American studies from Reed College, she thought she could figure it out.

Three decades later, she would earn her master’s in architecture and begin a new career. But just like the house, it would take a lot of tearing down and rebuilding, and many years of trying new things, first.

Leah grew up backpacking and rafting with her parents. She’s always felt most at peace in the outdoors. But she was also a bookish, high-achieving child, who developed the assumption that to be successful meant becoming a doctor or a lawyer. So. That’s what she would do.

At Reed, she majored in American studies, with firm plans to become a lawyer. But those four years were difficult.

She recalls being in classes full of brilliant students. “I was smart. But I wasn’t brilliant.” Suddenly not being the smartest kid in the room was distressing, and she had to work extra hard to keep up. Bouts of depression followed. Depression runs in Leah’s family, but she suspects all that time spent cooped up studying, and the pressure to keep up with her classmates, were contributing factors.

After graduating, she got a job right away as a paralegal.

She liked the challenge of the work, but the environment felt combative. Everyone was always arguing. When she left the office each night, she was relieved to go home and work on her house. She loved the physical labor and the satisfaction of slowly seeing her progress. The house was becoming a home, one nail at a time. And it

occurred to her: if she could remodel her own house, perhaps she could work on others, too.

In 1995, Leah quit her job as a paralegal to become a contractor—without any formal training. Whatever she didn’t know how to do, she’d teach herself.

“I thought I could do anything,” Leah recalls, laughing. “That’s what you think when you’re young.”

She wasn’t entirely wrong. She got work right away, painting and doing finishing work. Eventually she went to Portland State for a second bachelor’s degree in architecture, and for the next decade she worked on designs for homes, restaurants, and bars. But most of her work was limited to writing reports; the program wasn’t accredited, and she still wasn’t a licensed architect. That would require graduate school, then accumulating enough hours to earn her license and passing final exams. She had two young children at the time, so continuing with school didn’t seem feasible.

In 2008, the economy crashed; suddenly no one needed or could afford new construction. Leah lost her job, and without a license her options for architecture work were limited. With two kids, she had to figure something out, fast.

Leah knew the bar business well, from working on designs. She loved craft beer. And she was always looking for a place where she could enjoy a pint and also bring her kids. Maybe she could run a pub?

In 2010, she went for it and opened a family-friendly beer bar, and then another the following year. The social atmosphere of the bar business engaged her extroverted nature as office work never had. Managing her teams and keeping customers happy was hard work, and the long hours were tough while parenting, but overall “it was a huge success,” she says. Then her dad got sick.

Leah’s parents owned a winery in Northern California, and now her dad couldn’t work. They needed help keeping the business afloat. So Leah moved her family to Humboldt County, so she could take over. Again, she hit the ground running, tripling the winery’s business in mere months. The outdoor tasting room was regularly packed, and they were

producing more wine than ever before.

In 2017, she sold the Portland pubs; they were just too hard to manage from a distance. For a couple of years, the winery was thriving. Then came the pandemic.

Leah had 18 weddings booked for the upcoming season; they all had to be canceled. “We had a very successful, profitable business that came to a screeching halt.”

Suddenly there were no wine flights to pour or events to plan. Instead, she spent long days alone in her car making deliveries. Her life, once full of customers and staff, went quiet. It was just she and her family; the rows of grapes outside of their home sitting quietly, ripening while the world retreated.

In the years Leah lived at her parents’ winery, people would often tell her she was lucky to live in such a beautiful place. “But I found it to be very lonely and strange,” she says—especially after lockdown. “What I really wanted was to be around people.”

The pandemic gave Leah time to think about what was most important to her. What did she really want to focus her energy on? Community came to the forefront.

She enjoyed running the pubs because they brought people together. But the alcohol and the customer service angle didn’t feel right. Slowly, in the quiet of lockdown, two seemingly disparate things came together for Leah. She missed building things. And she missed people.

She wanted to build things that brought people together.

Aaron Good, the former Nike employee who became a therapist and career counselor, often counsels people who are having a crisis of purpose. “They’ve gotten to a point where the work they’re doing isn’t fulfilling anymore. Or the mission that got them there no longer seems relevant.” But starting from scratch can be a huge commitment. Part of Aaron’s intake process with new clients is to break down the financial risk versus reward of changing careers. What is the minimum they need to earn to

I was a telescope technician for UCLA, studying helioseismology at Mt. Wilson Observatory. You’ve heard of earthquakes. Well, helioseismology is basically the study of “sun quakes.” I was living on a mountain in Southern California and had a blast studying the sun.

In the mid-1990s, just half a dozen years after the web was invented, I created a website for the telescope where I worked. I really enjoyed creating and maintaining the website. Meanwhile, having always been interested in baseball history, in my free time on the mountain I did a lot of baseball research. Then everything came together in the late 1990s when a friend at the National Baseball Hall of Fame reached out and said, “Hey, we have a job opening as webmaster.” Happily, I got the job, eventually became a curator, and now head the museum’s curatorial department.

Not too many folks will pay you to study baseball history. Frankly, there are more jobs as a major league baseball player (hundreds each year) than a baseball researcher or historian. So, when I got that lucky break, I had to take advantage of it. I had to give it a try.

I loved what I did on the mountain in Southern California, working in astrophysics for over a decade. And now I’ve been at the Baseball Hall of Fame for a quarter century, having made my avocation my vocation, which is pretty great.

make ends meet? What’s their target? What kind of training or education will they need to pursue this new path, what will it cost, and how can they get it done most efficiently? Could they continue working their full-time job while going to school? Can they save enough to cover a period of unemployment?

In 2021, Leah enrolled in a two-year program to earn her master’s in architecture at the University of Oregon and moved her family to Eugene.

She made it work financially by assessing her expenses and cutting everything that didn’t seem absolutely necessary. She canceled streaming services, stopped eating out, and downsized to a small rental home, in walking distance to her kids’ schools and the University of Oregon.

Leah recalls how the light in the fridge flickered, glaringly, and most of the blinds were broken. The paint was peeling and the rooms were small. But she spruced it up with fresh paint, lots of artwork on the walls, and some flowerpots in the front yard.

Other challenges related to being a student again at 50 (her next oldest classmate was 26) proved more significant.

Instead of the perceived intelligence gap that vexed her as an undergraduate, there was a very real age and experience gap between Leah and her classmates. The other students knew their way around the software they’d work with in their program. That was all new to Leah. But she had on-the-ground experience with both design and construction. Her hands knew how to build many of the structures her classmates were drawing.

“Reed taught me to work really hard,” she says. She felt behind on the technical side of designing, but she knew how to study and how to learn new things.

Also, Leah had a purpose. Along a meandering path from one job to another, from contractor to pub owner to winery manager to graduate student, she had collected knowledge about herself and the impact she wanted to have on the world.

The time Leah spent living in her parents’ home while she managed their winery had convinced her that the way

Aaron Good ’01 worked at Nike for over a decade before deciding he wanted to have a greater impact on the world through his work. He’s now a therapist and career counselor in Portland.

we build houses is not conducive to our lives. Watching friends face challenges with aging parents who needed increased assistance, too, led Leah to think more about housing options. She started considering architecture as a way to make people’s lives easier and more sustainable.

have privacy. She thinks a lot about the dramatic increase in autism diagnoses in the last few decades. The housing available today is not conducive to parents who need to support grown children who are neurodivergent or living with disabilities. Also, she tells me to consider the homeless people suffering

“We’re not shooting to be 100% sure of something.”

In June of 2023, Leah graduated with her master’s. She is now working on accumulating enough hours to earn her architecture license. Every week, she flies somewhere to inspect a new commercial building and file a report. Once she has her license, she will focus on infill housing.

Existing neighborhoods, to Leah, are full of potential to become more communal and house more people while reducing the environmental impact of individual homes. Building smaller houses on existing lots creates more supportive living environments, where parents can move closer to their grown children and grandkids, or vice versa; where people can live together and share resources, but also

from addiction or mental health crises. What if they had friends or family who could have offered them housing at earlier signs of trouble, before they were living on the streets? Better housing design has the potential to improve the lives of so many. Leah is determined to be a part of that.

Some loans were needed to pay for grad school, but Leah taught classes and her teaching stipend kept her debt minimal. She’s not too worried about paying it off, because she’s confident she’ll find work doing what she really wants to do.

“If you’re able to adjust your life, and you’re able to pick up and move to do the thing you want to do—you’re going to figure it out,” she says. “You just need to be creative.”

“We’re not shooting to be 100% sure of something,” says Aaron. When clients are in what he calls the “exploration phase” of their career change journey, they’re often ambivalent about which direction to take and how.

A career change doesn’t have to mean quitting a job for something entirely new. There are often small steps one can take in the direction of a more fulfilling career. Maybe you stick with the same kind of work, but in a different industry that is more aligned with your values.

For instance, Sarah Kliegman didn’t really stop being a teacher and a scientist. Her days as co–executive director of OHA look very different from her time as a researcher or a professor. But she applies her knowledge in science daily.

“I’m so glad I became a scientist first.” Sarah says her background makes it easier to connect the dots, to teach people about what happened in the past and what can be done to make things better.

Aaron recalls a speech delivered at convocation his freshman year at Reed. “They told us we would all do amazing things like cure cancer and save starving children,” and that struck him as unrealistic. Even as an enthusiastic freshman, he worried they were being set up for disappointment.

But Aaron concedes that eventually, he did feel that pull to do something bigger. After 13 years at Nike, “I was like, all right, I guess I do need to save the world.”

From majoring in anthropology to the years at Nike and the time spent questioning and researching what to do next, Aaron says he’s happy with the decisions he’s made along the way. They all led him to a place where his work has a snowball effect. When he helps people get even a little closer to work they care about, each one of them can go on to have a positive impact on the world. Maybe they’re not curing cancer, but they might be happier. They might make people around them happier. They might work harder at a task that ultimately makes someone else’s life a little better. Or, maybe, they will go on to save a little corner of the planet.

When Sarah moved back to Tonasket, she knew it was the right decision. “When I came home and didn’t have to leave in a couple of weeks, I felt so at peace.”

In 2020, OHA filed Clean Water Act lawsuits in U.S. District Court against Crown Resources Corporation.

“Our community will not stand for the pollution of our waters,” wrote Sarah in a press release. “The mine has not taken sufficient actions to either investigate the fate of pollutants at the site or to clean up the pollution. This lawsuit is intended to impel the company to clean up their mess.”

In 2022, a federal judge ruled that Crown Resources, the owners of Buckhorn Mountain gold mine, had indeed violated the Clean Water Act— thousands of times. The penalties are yet to be determined, but will likely be in the millions of dollars.

When Aaron works with recent graduates, they’re often “freaking out” about what they’re going to do with their lives. They see their friends getting ahead, and they worry they’ll fall behind or make the wrong decisions.

“I try to normalize those feelings,” he says. And he encourages them to just take the first steps, without worrying too much about the direction.

Reed seniors who meet with advisors at the Center for Life Beyond Reed are encouraged, similarly, not to focus too much on the particulars of first jobs. The “purpose-driven advising model” at CLBR instead emphasizes purpose.

“We know this generation is probably going to change careers a couple of times,” says Shania Siron, assistant director of career and fellowship advising at CLBR. “We want students to have the skillset to be reflective of what matters to them.”

Aaron emphasizes that first jobs are about building confidence, not necessarily picking a path to be stuck on for the rest of your life. And then, he says, you can shape your purpose and direction along the way. “There’s a tremendous sense of relief to hear that you definitely don’t have to have your professional life mapped out at 21.”

I was in my mid-30s, and I wanted to have a child. But I wasn’t earning enough for a comfortable life as a parent. And I was sick of the weekly grind of journalism. I went to a Reed reunion and ran into a nurse-midwife; she told me about her job, and I thought, I think that’s what I want to do. So I started looking at programs. I worked through the prerequisites. I got waitlisted at OHSU the first year I applied, and then I got in.

While I was in my master’s program, my partner and I split up. It was challenging to be a single parent while getting my master’s and being on call. I didn’t completely know what I was getting myself into. But nursing school was super cool. And the more I did, the happier I was.

Now I love my job. I don’t get bored. I get overwhelmed sometimes, but that’s normal. Now I’ve been a midwife since 2009, and I still learn something new all the time. People come in and ask a question and it’s like, I’ve never heard that question before. Let me go figure it out.

Are you a professional seeking a new job, changing career paths, or need graduate school advising? Reed's alumni network of career coaches and the Center for Life Beyond Reed can help.

See www.alumni.careers.edu to find out more or to volunteer as a career coach.

From her thesis at Reed to the remote wilds of Alaska, bush pilot Lana Tollas ’19 has always found a way to take flight

By Chris Santella Adams Photos by Ash

Photos by Ash

“Want to see some bears?” Lana Tollas ’19 asks from the pilot seat of the single-engine De Havilland Beaver aircraft that’s carrying three friends and me toward Pegati Lake, some 100 miles southeast of Bethel, Alaska. Which is to say just west of nowhere.

“Sure!” we speak into our headsets. Lana eases back on the throttle and banks the plane to the left. A thousand feet below us, a mama grizzly hustles her two cubs along, alternately moving forward and stopping to make sure they’re keeping up. She eventually guides her charges into the creek, out of sight.

“Sometimes we’ll see moose or caribou here,” Lana adds as she climbs the Beaver out of the Eek Valley, back on track for Pegati. “But mostly it’s grizzly bears.”

This is less than comforting news, as my group is about to embark on a nine-day river float with just six cans of bear spray and our limited wits between us and Ursus horribilis. But it’s not our first rodeo.

Nor is it Lana’s.

It was not a direct route that brought Lana to the Alaska tundra. She was born in San Diego, but her mother moved her and her sister to Kenosha, Wisconsin, when she was four, seeking a quieter

environment for the girls to grow up in. There was a small airport near their house, and Lana was drawn to it, wanting to meet some “good, grounded midwestern people.” It was there that she eventually learned to fly. “I didn’t have a dad growing up, but I joined a flying club. Suddenly I had a whole bunch of male authority/dad figures in my life. Since my mom is of Indian descent, I felt like a bit of an outsider. Being involved with the flying club was a way to become part of things,” Lana told me in an interview some months after our flight.

Lana’s first flight in the cockpit was at age 16. She would fly once a week with her instructor. “I found it hypnotizing—it still feels that way. When you’re learning how to turn, it feels like the world is turning, but you’re staying put. I fell in love with that feeling. It was amazing.”

Flying was also a way to gracefully steer clear of the party scene that was popular with a lot of her peers. “When the other kids were getting ready to party, I told them that I had to head

in, as I was flying the next day. That wasn’t considered lame; the other kids’ response was, ‘Wow, that’s so cool.’”

However, Lana didn’t thrive in high school. “My school did not encourage a culture of curiosity, and I had poor grades,” she recalled. In fact, she was kicked out senior year and worked at Starbucks fulltime. Lana’s mom gave her a book called Colleges That Change Lives; it was organized by region, and she looked through thinking about the places where she might want to live—St. John’s in New Mexico, Reed in Portland. “Everything you hear about Reed says it’s a self-selecting place, very intellectual. I had good test scores and essays. I think my poor grades put traditional colleges off. But Reed saw some potential.”

Lana was a pure math major her first two and half years at Reed, and loved it. But somewhere toward the middle of her junior year, she hit a wall. “It was the first time I found myself at the edge of my capabilities, and I couldn’t push through. But I realized that there were skills I had that involved an intuitive human understanding that were

less applicable in math, but could find application in a different discipline— like economics.”

Soon Lana found herself in a macroeconomics class taught by Jeff Parker [economics 1988–2020]. “Sometimes it went well for Lana, sometimes it didn’t,” he told me. “But she decided it might be more fun than math, so she signed up for macroeconomic theory, the most difficult course in the department—even though she’d completed few of the prerequisites. She nailed it. Her energy and passion were inspiring. There was no question that she should be an economics major, even though she was making this call in the second semester of her junior year. She got it done.”

With the help of an alumnus, Jon Farr ’93 (who’d also studied under Parker), Lana was able to build her thesis around her interest in flying. Farr was working with a company called FlightStats (now Cirium) that had accumulated massive amounts of data on every flight in the world. “It wasn’t entirely clear what thesis might emerge from the data set,” Parker said, “but

there was an opportunity. And Lana seemed like a great match, as she had both the quantitative skills and a statistics background.” Ultimately, they decided to look at the following question: when there’s a weather delay/cancellation/airport closure, how long does it take flights to recover to being on time? “We thought of the variables— the capacity of a given airport to add additional flights by runway capacity; where can you squeeze a flight in?” Parker added. “She built a model using data from a dozen airports, and it was a monstrous task. There was no computer system on campus big enough to crunch the data; we had to set it up in the cloud.”

Weekly flights around greater Portland helped Lana keep her sanity her senior year. She had a standing appointment every Tuesday morning with an instructor named Frank Parker in Vancouver. (Technically she already had a private pilot’s license; insurance required an instructor on board.) “I’d go to Vancouver, and we would hop from grass landing strip to grass landing strip

all morning. There are a bunch in southwest Washington.”

Her thesis work led to job offers as an aviation consultant. She packed off to O’Hare in Chicago for a nine-to-five desk job. It was soul-killing. “I knew it was going to be bad after the intellectual high of college, doing my own research,” she said. “But it really sucked.” It led to one of the most questionable decisions of Lana’s life: at the height of COVID, she quit a stable job, bought her own plane (a Super Cub PA-12), and became a flight instructor in northern Illinois.

“I worked a few side jobs in the Chicago suburbs in addition to my analyst job, and budgeted tightly, with no drinking and no meals out,” Lana said. “Between my three jobs and help from my mom and uncle, I was able to buy the little three-seat plane—about the same cost as a modest car.” She moved into a hangar, bringing an Instant Pot and a box full of books and clothes. She split her time between apprenticing as an aviation mechanic and teaching, when she had a student. “At the time, I was living at one airport and working at another. I

The town of Utqiagvik (formerly known as Barrow) pictured a few days before the winter solstice. In Utqiagvik the sun sets on November 18th and rises again on January 23rd. The 67 days in between are lit by a few hours of indirect light, which illuminates the coastal plane upon which Utqiagvik lies. The Arctic Ocean can be seen beyond the lights of town in the background.

was commuting to work by plane; it was 45 minutes driving, only 15 by air!”

Then she began looking north.

The old saw used to go that America’s outliers—psychologically, politically, whatever—rolled towards the nation’s edges, with California and Florida being the most likely spots for them to collect. One could make the case that, at least on a per capita basis, even more heretics make their way to Alaska, where an independent, individualistic approach to life is often a necessity, not an indulgence. Want to eat this winter? Better net some salmon and shoot a moose for the freezer. Need to fire a woodstove? Better get in some wood. A lot of wood (one homesteader website recommends about eight cords, or 24,000 pounds if the logs are dry).

But if your passion is flying light commercial aircraft, Alaska is not such an odd place to set up shop. Alaska boasts over 665,000 square miles. That vast area is served by roughly 14,000 miles of public roads, providing access to about 20% of the state. Be it a small city like Bethel (population 6,264), a Native Yup’ik village like Quinhagak (population 776), or a wilderness river like the Kanektok (population zero, if not counting bears), the only way in and out—particularly in the summer season, when rivers are not frozen—is by bush plane. Pilot opportunities abound, especially for those who are willing to commit to flying year-round. The work is constant, and pilots can quickly accumulate the flying hours they need to attain higher levels of certification, which translate to higher rates of pay and expanded flight opportunities.

Lana saw an Instagram job post calling for flight instructors in the winter of 2021. They wanted instructors who could teach on planes outfitted with skis and then floats. She got the job and moved up to Talkeetna (about 100 miles north of Anchorage). It wasn’t a good fit and didn’t last. Float season had begun, and everyone had finished their seasonal hiring. What now? She started making calls. Her persistence led to her first commercial flying job, out of Bettles (population 25), up in the Brooks Range. She was essentially the office

lady, fueling planes and loading them. She was allowed to fly planes that had wheels so she could get on insurance. “That was my first exposure to the Beaver,” she added. “They promised I’d be flying planes the next year. Becoming a pilot is a game of accumulating hours. You have to keep paying your dues.”

The following winter brought her to Bethel —a major aviation center for western Alaska, as the city serves as a supply center/social services clearinghouse for many of the region’s Yup’ik villages. “It’s very rare to get a flying job in Alaska without putting in a winter in Bethel,” Lana observed. She estimates that 75% of professional pilots in Alaska have worked out of Bethel at one point or another in their careers. One of her first first commercial winter flights (with a Cessna 207, notoriously harder to fly in instrument conditions) has stayed with her. “It was dark and snowing when I took off. I could see a big storm coming in; I was almost immediately in whiteout conditions, so I was flying using instruments as opposed to flying visually. As I was white-knuckling my way back to Bethel, I was thinking that I was really having to work for this. It wasn’t like summer flying.”

Nearly all the winter flights involve the transport of mail, supplies, and villagers. In the summer, recreational visitors—mostly anglers and hunters—are added to the mix, and the Beaver, outfitted with floats, takes on greater importance. “Beaver pilots are a dying breed; it’s hard to find pilots with experience,” said Justin Essian, owner of Papa Bear

Adventures, an outfitter based in Bethel. “Word of mouth is the best way for outfitters and pilots to connect. That was how I met Lana. She had a good attitude and outgoing personality. Since she had experience piloting a Beaver, it helped lower our insurance costs. And she really wanted to be in Alaska. That’s important, as I want people who want to be here. It’s hard work, long hours. But you’re going to be treated well, and you’ll be part of the family.”

“I have to say that I was a little skeptical about hiring a woman as a pilot.” Essian told me. “Not because of Lana’s flying skills, but because of the physical portion of the job. You have to lift 120pound rafts, 150-pound moose quarters. But I figured that if she has the skills and fit the general bill, she’ll figure the moving-heavy-things-around part. As long as the job gets done, I don’t care how it gets done.” And she did. For an entire summer prior to working with Papa Bear, her only job had been to load and unload rafts. In the off-season, she lifts weights. In other words, she was fit and quickly proved her mettle.

Alaska bush pilots are legally required to have 10 hours of rest daily, which means they are on call to fly up to 14 hours a day. Lana’s summer days begin at 8 a.m., getting the airplane fueled and ready to go. Most days, she’ll fly out two or three groups of guests. That means loading the Beaver (capacity is up to 1,200 pounds), flying to the lake or river where the guests will start their trip, and potentially picking up another group that’s coming off one of

Lana stands on the ramp at the Deadhorse Airport in -25°F after loading her airplane full of cargo and passenger baggage. She started the morning in Fairbanks, flew a scheduled run from Fairbanks to the native village of Kaktovik, and then to Deadhorse. She will end the day in Utqiagvik, where she will work for two weeks before returning home to Fairbanks.

Opposite: Lana loads passengers onto a Cessna Caravan for a scheduled flight from Deadhorse (Prudhoe Bay) to Utqiagvik via the native village of Nuiqsut.

the rivers Papa Bear serves. It’s usually an hour out and an hour back, plus loading and unloading. Pilots are paid a day rate. “This discourages pilots from making any bad decisions about trying to fly under poor conditions for money’s sake,” Essian added.

Moose hunting season may be the most trying for bush pilots; it’s certainly the messiest. “I single-handedly flew out 24 moose,” Lana said. “The Beaver can fit 2.5 at a time. We have tarps down in the plane, but once the quarters are unloaded back in Bethel, we have to hose everything down with bleach and hot water. I do the same for myself.”

Do angling and hunting guests second-guess her judgment? Occasionally. “Sometimes there’s a guy who thinks he knows more about this than I do. You can easily get frustrated with the

masculine world I work with. But I try to laugh it off. If I’m going in to pick up hunters that I didn’t drop off, I’ll show up in my hot pink raincoat, and wear lipstick. The hunters see a Beaver land in the middle of the backcountry. I love the look on their faces when I step out: ‘All right boys, let’s get that moose on board.’ The moments when I do a good job in pink make up for any chauvinism.”

There’s a fair bit of downtime if you’re an Alaska bush pilot, especially in the winter. Lana makes hers as productive as possible. She reads a good deal and has been working on a novel, the fictionalization of the life of Reed alumna Joann Osterud ’68, who went to Reed in the 1960’s and later became a stunt pilot and Alaska Airlines’ first female pilot [In Memoriam, December

Lana fills the Cessna Caravan with jet fuel at the Fairbanks Airport before her scheduled departure at 9 a.m. The sun will rise at 11 a.m. in Fairbanks.

The expansive Chandalar River extends below as Lana flies from Fairbanks to Kaktovik. These wide river valleys are used by Alaskan pilots like roads to navigate within mountains, rivers defining the lowest and most hospitable terrain.

2017]. “When I was at Reed, there was lots of civil unrest,” she noted. “It was similar for her. In a way, I’m telling a familiar story.”

While flying around the bush may not be in Lana’s long-term career plan, she hopes to ride it out as long as she can. “I worry that we’re getting close to the end of manned bush flying in Alaska,” she opined as Pegati Lake came into view during our flight. “The National Park Service [which oversees 54 million acres in the 49th state] is trying to make access into parkland more humanpowered. The Beavers are old; the last one was built in 1967 [and only 1,657 Beavers were manufactured by De Havilland Canada]. We keep them working, but they won’t last forever. There’s also a push for more autonomous flying. There’s already a Caravan that flies

autonomously. Within my lifetime, the jobs I’m doing won’t exist.”

Lana can easily imagine graduate school in her future. Her economics background and statistical skills would certainly lend themselves well to a career in natural resource management or environmental policy. But right now, flying is a great way to spend a day, getting paid doing something she loves.

“I think there’s a perception that all Reed students go on to become professors,” Jeff Parker reflected when we spoke about Lana. “But I think her story is an excellent example of the range of interests Reed students have beyond the classroom. They go in a lot of different directions following those interests. Given her adventurous nature and passion for flying, it’s not hard at all to think of her as a bush plane pilot.”