66 minute read

VINTAGE

1893

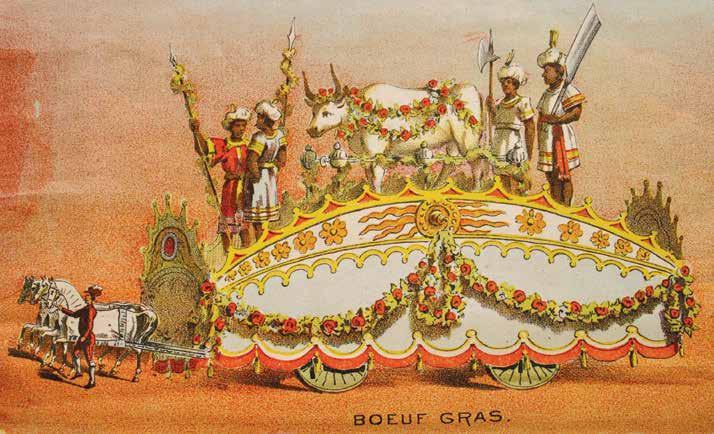

rom 1872 to 1900, the Rex organization – as did the Mystic “This was the height of the Golden Age of Carnival,” says Hales, “and

FKrewe of Comus for a short time years earlier – carried Rex and other organizations filled the streets with ever more elaborate and on the ancient French tradition of featuring a live Boeuf sophisticated parades. Somehow a live ox (let alone Old Jeff) in a wagon, Gras, or fatted ox, in its annual Mardi Gras procession. even if it represented a significant traditional link to the beginnings of It marked the last day meat could be eaten before Ash Carnival, just didn’t fit in anymore.” Wednesday and Lent. In 1959 Rex returned the Boeuf Gras to its parade line up, not as a live

As seen in this colorful lithograph published in the New Orleans “Daily animal but with a papier-mâché bull, which Hales describes as looking Picayune” on Mardi Gras Day, 1893, Rex revelers, dressed as butchers, more like “El Toro than a stately symbol of an ancient tradition.” But even paraded a live ox atop a float as if leading it to slaughter and Rex’s Boeuf Gras that has changed over the years. the main course at that night’s feast ending carnival. The gesture Float, Mardi “Today’s Boeuf Gras,” says Hales, who reigned as Rex in 2017, was often more symbolic than an actual roast-beef-on-hoof Gras 1893. Courtesy of Dr. “is massive, garlanded and surrounded by white-coated chefs. This dinner. Rex often paraded Old Jeff, a bull borrowed from a local Stephen Hales traditional symbol seems secure and would surely be recognized by stockyard. On other occasions, says Rex archivist and historian anyone familiar with the symbolism and imagery of early Carnival. Stephen Hales, newspapers advertised “choice cuts from the boeuf gras” The connection through centuries of Carnival celebrations represented by could be purchased at local butcher shops. Mardi Gras 1900 was the last this one symbol, the ancient figure of the Boeuf Gras, adds to the beauty time Rex included a live ox. of the tradition carried on in New Orleans each year.”

THE NEXT GENERATION

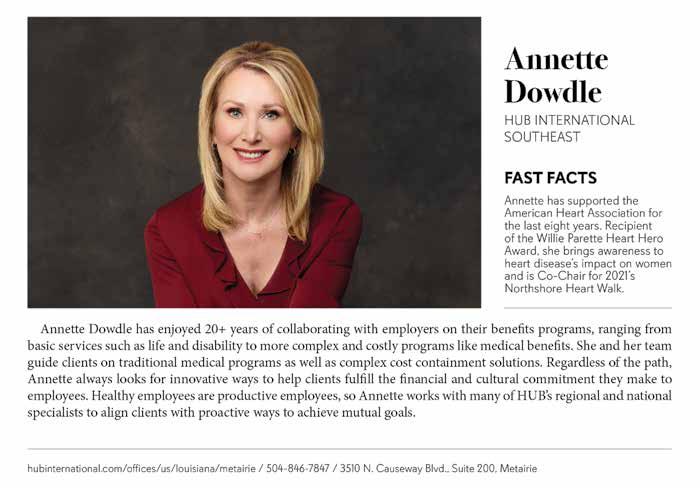

Six changemakers leading in a new way

BY BETH D’ADDONO PHOTOGRAPHY BY CRAIG MULCAHY

If not now, when? While 2020 had so many life altering implications, it will forever be defined as the year that Black Lives Matter became a rallying cry and “I can’t breathe” a collective dirge. Black change makers are passionate about a host of social ills that affect their community. The common thread that unites each of them is the urgent business of making a difference, to push back against ignorance and systemic racism with revolutionary results always the end game. These six change makers of color are making dramatic strides in their respective fields, transforming lives in ways little and large. Because change doesn’t happen in a vacuum, support one or all of them and see what persistent leadership, resources and dreaming big can accomplish.

Before COVID-19 created a global health crisis, Erica Washington collected data on all kinds of infectious diseases, from heavy hitters like MRSA and Ebola to more common strains of measles and mumps. “Now it’s all COVID, all the time,” said the Baton Rouge native who moved to New Orleans to earn her master’s in public health from Tulane. “All of our team is focused on the pandemic. We’ve onboarded a lot of staff to handle the workload.” Washington always wanted to work in public health. “It’s an altruistic field of service as a vocation. Being involved in public health makes you feel purposeful.” She toils in the infectious disease epidemiology section for the state, working with a team to coordinate data surveillance as it relates to COVID-19, working with healthcare facilities to keep frontline workers safe. Although there’s nothing sexy about mining data in the name of public health, it’s painstaking work that provides the state with the kind of metrics needed to shape policy and save lives. Washington has always loved science, making her an anomaly in her family. “I’m an only child who comes from a family of artists. “I can’t even draw – my love for science made me an outlier for sure.” She is most proud of the job the state is doing to support healthcare workers. “We do a lot around infection prevention. Our power is data – using it to show which are the most impacted communities, which all too often are communities of color. Yes it’s a dire time, but we can use these metrics to improve our residents’ quality of life.” Monitoring healthcare-associated infections across the provider spectrum makes up most of her job. “We work with facilities to execute prevention and surveillance to track how infection is spreading.”

Washington points to her time working closely with Dr. Raoult Ratard, the dynamic Louisiana State epidemiologist who passed away in April, as the most influential relationship of her career.

“He was an amazing mentor and I’m so thankful for his leadership. The hallmark of any leader is to create more leaders. Dr. Ratard’s approach to communicating, whether with the public or internally with the department, was to always be sure the message was digestible and relatable. He used every moment as a teaching moment, which kept me learning all the time. He took a commonsense approach to public health which I try to emulate.” Washington has been recognized many times over for her leader- A PANDEMIC ship, dedication and public service. IS THE She earned the Reverend Connie PERFECT Thomas Award for her years of STORM service and dedication to Luke’s House, a clinic that provides free medical and mental health services to more than 800 medically underserved and uninsured people per year. She was also recognized as a White House Champion of Change for Prevention and Public Health. Additionally, she was a 2016-2017 Informatics-Training in Place Program Fellow through Project S.H.I.N.E. (a collaboration between the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists, and the National Association of City and County Health Officials) that seeks to increase the informatics capacity of health departments nationwide.

Washington feels hopeful about the vaccination programs rolling out, while acknowledging the virus’ ongoing toll. “Communication is a huge part of public health. I feel that in all of this, I’ve been able to key into very human moments, where people really just want someone to listen to them. It’s interesting to actually be present with folks, help them to understand what’s going on. Empathy goes a long way. This is larger than us. Empathy is what is going to help us supporting our front line workers, impacted residents and communities.”

It’s a lot, dealing with the reality of a raging pandemic, day in and day out. Maintaining personal balance in her life outside of work is more critical than ever. “In order for us to be effective, we have to recharge. That’s always a challenge.” She finds solace in cooking – crawfish fettucine is a specialty - and assigned herself a pandemic reading project to help clear her head. “I’ve never read the Harry Potter series and I’m on book four. I’ve avoided spoilers for 20 years. Now I’m finally figuring out who Voldemort is and why he’s after Harry.”

When Ahmaud Arbary was chased by armed white residents and killed for “running while Black” in a South Georgia neighborhood, William Snowden’s heart broke.

“What happened to Ahmaud wasn’t more horrific or tragic than what happened to George Floyd, but it hit close to home. I had the privilege of not being shot and killed while running when I was 14.” What happened to Snowden – being stopped by police while running far behind his high school cross country team through a white Milwaukee suburb – was not the last time he was profiled as a black man. The son of a black father and a white mother, Snowden learned a few critical lessons from that experience. “I learned that people were going to look at me and assume certain things because of the color of my skin. And seeing my parents, especially my mother, challenge that police authority taught me that when a person without power is wronged, someone needs to stand up for them to be sure that wrong is corrected.” This early life lesson was pivotal to Snowden’s decision to go to law school. He saw his choices as either to lean forward and embrace equity and fairness or fall back to a broken legal FIGHTING MASS system instilled with white supremacy. Because this country’s criminal justice INCARCERATION system has a disparate impact on Black WITH SOCIAL and brown people, Snowden moved JUSTICE to New Orleans in 2013 to become a public defender. “Louisiana is the prison capital of the world,” he said. “This state is locking up too many Black people. I felt it was a privilege to stand up for people who couldn’t afford to pay for a lawyer.” Snowden arrived at the public defender’s office with a fire in his belly. “I had the desire to use my trial skills to give poor people the best representation that they could ever get,” he recalled. What he quickly realized, however, was that the state’s draconian laws actually prohibited him from doing just that. Because of the three strikes law, a throwback to the war on drugs in the 1990s, a felony drug possession, whether it was of marijuana or heroin, could get the defendant a life sentence in Angola. “The design of the system drove plea deals instead of offering the opportunity to take a case to trial,” he explained. “Victories became reducing a felony to a misdemeanor, for getting credit for time served. Knowing what was at stake, I leaned on my clients to take the plea deal. I got to the point that I was so frustrated at the kind of attorney I’d become, I just got burnt out.” That frustration, with the incarceration cycle, the sense of being a cog in a wheel, of not being able to affect policy, sent Snowden to the Vera Institute for Justice. An outgrowth of the Manhattan Bail Project dating to the 1960s, Vera Institute of Justice works in partnership with local, state and national government officials to create change from within. Active in 40 states, the Institute tackles the most pressing injustices, from the causes and consequences of mass incarceration, racial disparities, and the loss of public trust in law enforcement, to the unmet needs of the vulnerable, the marginalized, and those harmed by crime and violence.

In his role as director, Snowden casts a wide net. He leads workshops around the country to discuss how implicit bias, racial anxiety and stereotypes influence actors and outcomes in the criminal justice system. At the start of the pandemic, with jails a petri dish for infection, Snowden led conversations with judges, identifying non-violent offenders over the age of 55, many with bail set below $5,000 for possible release. About 250 prisoners were set free. He also launched The Juror Project, a passion project aiming to increase the diversity of jury panels while changing and challenging people’s perspective of jury duty.

With Jason Williams newly elected as the city’s district attorney, Snowden is engaged on several levels. “First we worked to educate people as to what they can expect from a DA, how that office can wield its power for good.” Post-election, Vera is providing technical assistance to create a data infrastructure to allow for transparency and accountability, all designed to set the new DA up for success, giving him the tools he needs to keep his campaign promises.

While the Black Lives Matter movement shed a blinding light on incidents of police brutality and racially motivated violence, Snowden still remains hopeful. “Hope is a survival tactic. If we don’t have a vision, a north star, then we aren’t doing the work we need to do,” he said. “We need to have difficult conversations, create spaces for truth telling about this country’s history. Losing faith in the ability to change what our reality is isn’t an option.”

Black women are four times as likely to die in childbirth in the state of Louisiana than white women. In Texas that number is nine times as likely, in New York eight times. As a Black mother, Nikki Hunter-Greenaway, aka Nurse Nikki, takes that very personally. Hunter-Greenaway, a Dallas native who has lived in New Orleans with her husband and three children for 13 years, is a trained doula and nurse practitioner who is also internationally board certified as a lactation consultant. Her mission, to not just help women survive childbirth but to thrive before, during and after pregnancy, speaks directly to her own experience. The year 2012 was a banner one for HunterGreenaway. She graduated in May with her masters from LSU as a nurse practitioner. In June she moved into a new home in Pigeon Town and in July she had her first child. With her husband busy with work and family out of state, she felt alone with her baby. All of that added up to a crippling case of post-partum depression. “I could barely get out of bed,” she recalled. “I felt like somebody should be checking on me.” Hunter-Greenaway had studied abroad in the U.K. during her undergraduate time at Northwestern University, and had seen how that country’s healthcare system supported women with pre- and postpartum home visits. Hunter-Greenway confided in her brother, a professor and pastor at Emory University. “He challenged me to be the change I wanted to see,” she recalled. “Therapy is almost taboo in the Black community,” she said. “Depression isn’t something we talk about. The common belief is that you pray and everything works out. That isn’t always the case.” It took nine months for her to feel like herself again. She started her business as Nurse Nikki, intent on educating women about

NIKKI HUNTERGREENAWAY

FOUNDER, BLOOM MATERNAL HEALTH

post-partum depression and the host of other reasons pregnant women especially communities of color, are at risk. With Louisiana currently 49th in the U.S. when it comes to breastfeeding, she focused on lactation education with her clients. Her practice grew by word of mouth, but it took four years for her to get her first Black client. “We have mommies and aunties surrounding us, the feeling is, ‘I don’t need help, I know what to do.’ But the numbers tell a different story.”

Black women face implicit bias in healthcare. They are expected to have hypertension, so the condition often goes unchecked. Pain isn’t managed as it should be. Information isn’t always provided. “My biggest frustration is politics - we shouldn’t be politicking somebody’s health.”

As a member of the Maternal Child Health Coalition, she was asked to speak to City Council about the current health crisis facing pregnant women of color. “We’d come before council in October and there was hardly anybody there – nobody was listening. I never knew council members would come in and out of meetings during a presentation, get up and get coffee.” When the meeting was rescheduled for the following January, it seemed as though council was hearing the Maternal Child Health Coalition’s message for the first time. PROVIDING

“There were two council people at the table. PERINATAL CARE I’m not one to take the spotlight, but I just stood WHEN FAMILIES up and said, ‘We aren’t doing this.’ This problem NEED IT MOST affects every district in the city. I told them I’d wait until everybody was there.” As council members came back into the room to listen, Hunter-Greenaway had an out-of-body experience. “I went off script and spoke from my heart,” she recalled. “I said I was tired, tired of sack lunch meetings when mamas are dying. Y’all allocate money for so many things, if you don’t help mamas and babies you’ve helped nobody.”

As she expands her practice with its focus on women’s health visits at home, Hunter-Greenway finds creative ways to partner with non-profits like Covenant House and Kingsley House to get paid for services. While some insurance covers care, Medicaid still does not.

“I’m looking forward to providing more services as we continue to get grants,” she said. Grants from Tulane and Pelicans player Jrue Holiday and his wife Lauren helped underserved families get care as well as a supply of wipes, diapers and feminine hygiene products.

She’s added electronic medical records into the mix, another layer of documentation that can and should be integrated into all practitioner’s care. “We can all work together so there’s no gaps in information,” she said. “That’s how women and babies die. There is a huge gap between hospital and community. Really, it’s more like a cliff.”

When James Beard award-winning chef John Besh was accused of multiple cases of sexual harassment in October 2017, the scandal reverberated not just in New Orleans, but throughout the culinary world. He was one of the first high profile chefs to be so accused, fueling the #metoo movement that quickly crossed borders and industries, as women found their collective voice and used it to topple kingpins and serial sexual predators. Lauren Darnell had heard of Besh, but she wasn’t working in hospitality when her friend Shannon White made her a proposal. White took over as CEO when Besh exited the Besh Restaurant Group, now known as BRG Hospitality. She asked if Darnell would consider taking over the Besh Foundation as executive director. Established in 2011, the foundation provided scholarships, grants and loans to New Orleans businesses, chefs and culinary students of color. Since the scandal, the four culinary students being funded through the foundation were basically left to their own devices. Darnell had experience with non-profits – she’d been working as director of partnerships and programming for Son of a Saint charity, an organization that mentors boys left fatherless due to death or incarceration. “It really seemed wrong that these students going to culinary school in New York were not be getting the support they deserved,” she said.

Darnell took the job. “I guess I was naïve,” she recalled. “But I saw the alumni and the students and all the people they would help in the future just being overlooked. It felt like a lot of good people working in that restaurant group, women and people of color – their stories were just sucked up by a tsunami. Somebody needed to take this on.”

When she learned that one of the students getting ready to graduate on the dean’s list from ICC, the International Culinary Center (formerly the French Culinary Institute), wasn’t going to graduation because she couldn’t afford it, Darnell knew she’d made the right decision.

“I called her – of course you’re going, we’re covering the plane ticket and I’m going too – that was worth the months of what I’d put up with.” Darnell had to deal with plenty of blowback. She heard it all – she was complicit, she was hired as a token Black person, how dare she be involved in anything associated with John Besh. “I knew these students were worth it.” Darnell took the job on her terms. She installed MAKING SURE a new board, including CHEFS OF COLOR alumni. She changed GET THEIR DUE the name to MINO – Made in New Orleans Foundation and focused solely on scholarships, mentoring and business coaching for Black, indigenous and people of color in the restaurant and hospitality business. The board paid her salary for a year, until May 2018. After that, MINO was independent, no longer associated with BRG Hospitality.

“At the industry level, we amplify the voices of professionals of color and provide support to hospitality companies that are seeking to eliminate bias in their organizations,” she explained. Inclusive mentorship and educational opportunities are directed to lead spaces that have historically been exclusive.

Concern for social justice isn’t new to Darnell. Born in Lafayette, she moved with her family and two siblings to New Orleans East when her father, an attorney, took a job with a local law firm. “My dad’s always been the embodiment of service,” she said. “He taught us not to put ourselves first, to want to make a difference for others.”

From her father, who went to college and law school at Yale University, she learned there isn’t just one story, people have multiple experiences, and both being neutral and listening is critical. From her mother, the notion that you can be anything you want to be with hard work and persistence gained heft. “My parents came from modest means, but they always strived for great things. They instilled a love of new experiences in me, a passion for always growing and learning.”

Darnell was always aware of race and color. Her dad’s family was dark skinned, her mom was a light skinned Creole who grew up speaking French. “I knew I was Black but that I had a layered history.” When she went to the mostly white Academy of the Sacred Heart on St. Charles Avenue and would visit friends

LAUREN DARNELL

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, MADE IN NEW ORLEANS FOUNDATION (MINO) Uptown, she remembers seeing pictures of plantations on the wall. “I’d just think, ‘now that’s not cool.’”

“There’s just no escaping race. I wanted to be seen as a human, a girl interested in lots of things.” She remembers people assuming she was Puerto Rican when she was working in New York. “I’d say no, I’m Black. They’d say, you can’t be, you must be mixed. That taught me not to make assumptions which are always laced with our own bias.”

Although she didn’t get into Yale – “my dad was gutted” – she went to Pepperdine University in Malibu for a year, then finished her degree in anthropology and women’s studies at UNO, where she felt incredibly supported. “I’d been surrounded by 18-yearold privileged blondes in California, in New Orleans there were students of all ages, shades and voices.”

Over the years, she’s taught tennis to underserved youth in Harlem, worked for a PR agency representing the Center for Constitutional Rights, as a global event planner for an Israeli tech firm and a wellness and yoga instructor implementing yoga in a public school setting. “I’ve learned that I have to do something I believe in,” she said. MINO fills that bill.

“I’m most proud redefining how you serve and provide support for others. Help is too often given in the way we think it should be given, as opposed to asking, what is it you need? This past year has proven again that we need to have a conversation about race that’s real. We can’t be scared to talk about the past and present and what we want to create for the future.”

While she loves her city and its hospitality industry, she believes we can do better. The anonymous Black cook in the kitchen is a prime example, said Darnell. “The invisibility of the Black cook, that should no longer exist. There’s a Black cook in the back of the kitchen who is the reason for that barbecue shrimp recipe. We have to do better acknowledging the individual and celebrating their achievements. We are all better by lifting each other up as we go.”

Victor Jones may be the only guy with a master’s in education from Harvard whose first job after graduation was to teach kindergarten. “I know from experience how important early education is,” said Jones, 36. Born in Pascagoula, Mississippi and raised by a hard-working single mom, Jones grew up poor but always with a thirst for education. He saw his mom finish her degree and become the first person in her family to graduate college. That was 1989 and he was five. He believes that his early time in Head Start, a national program aimed at education and caring for low income kids and kids with disabilities, was a launching pad to his life’s success. “When I was seven, I knew what being on the honor roll meant, and it’s what I wanted,” he recalled. “Everything I’ve done in my career and life relates to my personal experience. I wanted those kids to see a man in a teaching setting. I was only 22. I think my students and I raised each other.” Jones went to Xavier for undergrad, followed by Harvard and then law school at Loyola. His academic prowess and low-income status became a passport to his education when he qualified for the Gates Millennium Scholars

A PROFOUND COMMITMENT TO EDUCATION

(GMS) Program, funded by a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Established in 1999, the program provided outstanding students of color a paid education, with the option for graduate school funding.

“The program took 20,000 high achieving students of color living below the poverty line and asked the question, what happens if money is not an option? What happens is that stereotypes get dismantled. I didn’t have to focus on anything but school. I had friends who didn’t meet the income qualifications and some of them couldn’t afford to go to college – they had to work instead.”

To say that Jones was mindful about his educational evolution is an understatement. Although he loved teaching early ed., he wanted to impact education on a systemic level. He went to law school with the intent of becoming a public interest lawyer specializing in educational law and policy. “I hadn’t seen anyone do it – and when I got out in 2012, I found that there were no jobs at the intersection of civil rights and education.”

Recruited by the local law firm Adams and Reese, Jones practiced corporate law but also had the chance to develop an education law practice with special expertise in special education law. “I see things from all angles, as a teacher, student and lawyer.” After working closely with New Orleans charter schools for six years, Jones took the next step and joined the Southern Poverty Law Center as a civil rights lawyer for children.

“I’d grown up idolizing Thurgood Marshall and Ella Baker, heroes in civil rights education. I wanted to be a part of that movement.” During his time with the Law Center, a few of his initiatives included filing a suit against the Louisiana State Health Department on behalf of 47,000 children in need of mental health services and co-authoring a bill that required school districts to collect data on students they disciplined. “Once we had that data we could act if a school was disproportionately disciplining a segment of the student population.”

Jones had been at the Law Center for two years when two things occurred that set him up for his next initiative. The pandemic happened, having an immediate effect on education; and he was offered the chance to impact policy as a senior attorney advisor to the state, exactly what he wanted to do. Based with the Board of Regents, a state agency that coordinates public higher education, Jones is at the forefront of working with the governor and department of education to help families, students and schools navigate an unprecedented health crisis.

His efforts have ranged from monitoring how schools are providing special education services to ensuring that some 5,000 students shut out of the ACT testing deadline by Louisiana’s hurricanes can still take the test and qualify for financial aid.

“Higher education was the one piece missing from my portfolio,” said Jones, who lives with his wife Nicole and daughters Nola, 6 and Zora, 2 in Algiers. “We really need more policies in place that tie all education together, a cradle to career pipeline.” Questions like how to develop harmonious policies at the state level to foster a more robust work force and keep all students involved with STEM projects occupy a lot of his focus.

Jones is proud of the work he’s doing and thrilled to be working closely with Kim Hunter Reed, Louisiana’s Commissioner of Higher Education, who is leading an initiative that calls for 60 percent of working age adults in Louisiana to hold a degree or similar credential by 2030. “The work she’s doing is phenomenal and very exciting.”

“Louisiana has been the lodestar of education policy for COVID,” he said. “We have experience keeping education running when everything around us has collapsed.” As a lawyer, researcher, policy maker and educator with insight into all stages of schooling, Jones is staying the course, doubling down and working to realize a singular over-arching goal: to impact education in Louisiana on a large scale. “I’ve lived it, I know what education can do. Every student deserves that chance.”

There are two pivotal realizations that set Latona Giwa on the course she’s following in New Orleans. The Minneapolis native recalls doing an internship while going to Grinnell College that involved working with homeless youth. Many of the young women she encountered were either pregnant or parenting. “I clearly saw that pregnant women are more financially vulnerable, more apt to become homeless. I wanted to learn more about how to support them. My research let me to the concept of a doula – and I knew that’s what I wanted to do.” She was 19. Giwa moved to New Orleans after graduation as a Grinnell Corps fellow, a role that involved community service and promoting leadership and social integrity. Working with the Jericho Road Episcopal Housing Initiative in Central City, she focused on quality of life issues for women. “I’d chat with women of all ages about their lives, their bodies, their motherhood and their birth experiences,” she recalled. “It didn’t matter if someone was 20 or 80, they remembered their birth like it was yesterday, and those memories were often traumatic.” Black women are twice as likely to experience pregnancies that result in early delivery, low birth weight, or even infant death, according to National Vital Statistics. After graduating from nursing school, Giwa founded the Birthmark Doula Collective in 2011 to provide

LATONA GIWA

FOUNDER, BIRTHMARK DOULA COLLECTIVE, REGISTERED NURSE AND CERTIFIED LACTATION CONSULTANT

emotional, physical, and educational support to mothers-to-be, most of them Black and poor. “Black infants are twice as likely to die in the first year of life as white infants,” she said. “That’s a preventable tragedy.”

“We know that Black women are not seen as whole people when they seek healthcare in America,” she said. “That’s exacerbated at the moment of birth, when a woman is most vulnerable.” Anecdotally, time and again, she hears women say they were not listened to, they weren’t able to get pain medication, or they were turned away from the ER.

In a “New York Times” article she authored in 2018, Giwa put it this way, “For Black women in America, an inescapable atmosphere of societal and systemic racism can create a kind of toxic physiological stress, resulting in conditions — including hypertension and pre-eclampsia — that lead directly to higher rates of infant and maternal death. And that societal racism is further expressed in a pervasive, longstanding racial bias in health care — including the dismissal of legitimate concerns and symptoms — that can help explain poor birth outcomes even in the case of black women with the most advantages.” Segregated health care, with women on Medicaid often seen on separate days of the BECAUSE week and at different BLACK locations from women BIRTHS with private insurance, is MATTER one reason for disparate care. “We know it’s not just biology killing Black women, it’s social conditions. So in the last maybe five years, there’s been a resounding cry across the country from organizations like mine, amplified by the media, to change policy on both the state and federal level.”

Giwa sits on the Louisiana Pregnancy-Associated Mortality Review board, which in the past four years has expanded its board beyond physicians to include pre- and paranatal practitioners including doulas.

There has been some progress, but not enough. “There is a move toward implicit bias training in hospitals in this city and state. Doulas, who serve as advocates for pregnant women, are increasingly being recognized as part of a cohesive care team. But, too often women are cared for by a rotating cast of nurses and doctors who they’ve never even seen before,” she said.

Fueled by Jim Crow laws that prevented equal access to healthcare, there is a long history of Black women giving birth with community support and midwifery. “When women are cared for in community there are better outcomes,” said Giwa, who is also training doulas from within Black communities.

“The benefit of having an advocate who knows about your birth history, how you express fear and pain and what your triggers are – it’s game changing.” Doulas are shown to reduce C-section rates really dramatically, by between 30 and 50 percent depending on the study, reduce the rate of unnecessary medical interventions, reduce the use of anesthesia and epidural medication, and thereby improve birth outcomes, Giwa said.

This spring will mark 10 years since she founded Birthmark Doula Collective. Two years ago, she co-founded New Orleans Breastfeeding Center, the first free-standing breastfeeding clinic in the state of Louisiana. The two organizations offer pregnancy support at every level, with clients charged on a sliding scale – more than half pay nothing at all, with those that can pay full fees helping to fund those that cannot.

When she’s not chasing grants, Giwa is engaged with policy initiatives to try and advocate for Medicaid and private insurance to reimburse for doula care. In the past five years, insurance has stepped up to pay for lactation services. Clients are never turned away, with doula services offered to women in prison, victims of domestic violence and homeless teens at Covenant House.

Looking ahead, Giwa’s focus is on insurance company advocacy. “I envision a future where everyone has access to both birth and lactation support whether their insurance is public or private,” she said.

The pandemic has fueled the doula and midwife movement in New Orleans. “Hospitals are where sick people go,” she said. “Pregnant women who are not at risk are not sick.” Giwa, who lives in Gentilly with her two daughters, one birthed at Touro and her youngest born at home, believes that all women deserve access to the birth they desire, whether that be a hospital, birth center or at home. “We support women wherever and however they decide to give birth.”

BUTTERFLY WINGS

STORIES FROM THE FLIGHTS OF CARNIVAL

BY ERROL LABORDE

For those who write regularly about Carnival, the quote to the right is both a source of beauty and frustration. The beauty comes from author Perry Young’s butterfly of winter metaphor and his skillful use of language (“tattered, scattered, fragments of rainbow wings”) all encapsuled into 41 words that capture the essence of Carnival. The frustration comes from that statement being hard (perhaps damn near impossible) to top. It is unfair to the future that the definitive paragraph of the season was already written 90 years ago. Nevertheless, Young leaves much to inspire us and to find nourishment in analyzing the season from a hearty feast of butterfly wings.

We take Young’s words seriously that the fragments are in turn the record of the day. So, we have set out to gather some of those remains in pursuit of Carnival’s finer moments. We know that there are too many memories for any collection, but in this, a year when we are denied much of the visual manifestation of Carnival, we thought we would offer a few. This is done in the hopes that come next winter the atmosphere and the spirit will again be free for Carnival to flutter at its most glorious.

CARNIVAL IS A BUTTERFLY OF WINTER, WHOSE LAST MAD FLIGHT OF MARDI GRAS FOREVER ENDS HIS GLORY. ANOTHER SEASON IS THE GLORY OF ANOTHER BUTTERFLY, AND THE TATTERED, SCATTERED, FRAGMENTS OF RAINBOW WINGS ARE IN TURN THE RECORD OF HIS DAY. - PERRY YOUNG, THE MYSTICK KREWE: CHRONICLES OF COMUS AND HIS KIN.

CARNIVAL STORIES

SATCHMO VS. A QUEEN

Don’t you hate when this happens? Your daughter is going to be a Queen on the same day that your idol is coming to town. That happened on Mardi Gras 1949 when Dolly Ann Souchon reigned as the Rex Queen. Her dad, Edmond “Doc” Souchon, was justifiably proud, but as an accomplished jazz musician, as well as a doctor, he was anxious to see the Zulu King, none other than Louis Armstrong. To serve both monarchs, Souchon passed up the traditional limousine ride to the reviewing stands with the Queen and family, and headed instead to the New Basin Canal, now the path of the I-10 Expressway. In those days, Zulu arrived by boat via the Canal. Souchon hurried to see Satchmo step off the boat to the appropriate applause and then scurried back to be with his family and the Rex entourage.

Doc Souchon’s morning was symbolic of a pivotal moment in the evolution of two of New Orleans’ greatest cultural contributions, the American Carnival and jazz. For many years the two traveled separate paths, having nothing to do with each other. Ultimately, they could not be kept apart.

Although the music was snubbed by Carnival in its early years, jazz gradually conquered not only the world, but its hometown Carnival too. In 1966, Rex introduced His Majesty’s Bandwagon, which featured a jazz band riding atop. By ‘68 there were three jazz groups rolling with Rex.

Even at the high society Carnival balls, where jazz was once regarded as a bastardized art form, the dance selections began including the music.

One person would carry the cause through the decades - Doc Souchon. One of the best known versions of Carnival’s anthem “If Ever I Cease to Love” was recorded with the raspy voiced Souchon doing the vocals - set to jazz time.

A 1968 book published in honor of the city’s 250th anniversary proclaimed correctly, “Only the city which produced jazz could have evolved New Orleans’ Mardi Gras of today.”

Jazz and Carnival: Doc Souchon never ceased to love either.

KEEPING BACCHUS WARM

When the newfound Krewe of Bacchus announced its inaugural parade to debut February 16, 1969, it heralded several innovations, one being a king who was not a typical local notable, but rather a Hollywood celebrity. Danny Kaye, multitalented in singing, dancing and acting, accepted the royal bid. Dressed as the God of Wine, Kaye positioned himself on the newly designed towering King’s float. There was excitement throughout the city as the parade formed, but also some concern - from Kaye.

The temperature hovered around the low 40s which from the perch of a float was cold, very cold. Although Kaye had been one of the stars in the movie “White Christmas,” this chill was beyond singing about. The Kingdesignate asked if there was something to be done to provide more warmth.

Bacchus officials scurried about. Floats, when done right, can be poetic masterpieces, but they are not known for their temperature control. As parade time approached, someone was able to rig together an electric heater strategically placed near the throne to provide royal heat. Then, from below, there were whistles and sirens and the parade began.

As the float turned from its den, Kaye dreaded a frigid reign. But then, as the float approached the street, Kaye was overwhelmed by the thousands of fans waiting to see him. Like any caring King he stood up and waved back while turning from side to side to greet the worshippers. He would not sit down again for the rest of the ride. The little heater projected its glow on an empty throne.

Years later Bacchus officials would recall the ride and how Kaye quickly forgot about the temperature. Nothing provides more warmth than an adoring crowd.

A phrase I use occasionally refers to something taking “a strange bounce” to describe a situation in which there was a sudden course-altering change. For attorney Staci Rosenberg, as she stood on St. Charles Avenue watching the 2000 parade of the Krewe of Ancient Druids, there was about to be a bounce of such enormity that the effects are still ascending.

Rosenberg was at the parade to see a friend and fellow lawyer ride by in the all-male krewe. Watching the maskers, she thought that being in a parade seemed like fun and then wondered how she could join a krewe. Then she thought a little more and raised the daring question: “Why not start a krewe of my own?”

Carnival history was about to take on a new character named “Weezie.” That would be Weezie Porter. Rosenberg recalled that she went home that night, called her friend Weezie, told her about her idea to start a new all-female krewe and asked her if she would join. As it happened Porter was hosting several gal friends, so she raised the question to them: Would y’all join?” Posterity was enriched at that moment because they all agreed.

In the weeks ahead Rosenberg, who says she knew nothing about creating parades, asked lots of questions.

“No one in the Mardi Gras community thought we would succeed,” Rosenberg recalled. “But this became an advantage also, since it led to the Kerns float builders charging us very little, since they thought we couldn’t afford it and we would fail. It was also hard to get bands, because it was a weeknight and they had never heard of us and thought they wouldn’t get paid.”

“While we talked to a few people,” Rosenberg continued, “I can’t say anyone outside of Muses really helped much. We were definitely the blind leading the blind, but it seemed to work out.”

Clearly the blind had the vision to make the right choices. A year later, February 22, 2001, Muses made its debut. While there had been all-female krewes before, this was the first to march on a weeknight at a time when women had become so much a part of the professional workforce.

The krewe also created opportunities for subgroups, notably walking clubs such as the Pussy Footers, Bearded Oysters, Lady Godivas and the Camel-Toe Stompers that have become part of the language of carnival.

Muses’ coveted decorated woman’s shoe souvenir quickly achieved status equal to the Zulu coconut. The krewe’s evolution would be one of the major developments of Carnival in the 2000s. One wonders how history might have been different had Weezie not answered her phone that night.

THE SURPRISE REX

There was a commotion outside of the home of John Ochsner’s parents’ home on the morning of February 10, 1948. For Ochsner, the day was already going to be special because that was his 21st birthday, but the other news superseded that, especially as dad, Alton Ochsner, was escorted to a limousine. Dad, it runs out was going to be Rex, but the family had known nothing about it.

For the rest of his life John would recall that morning. Usually when someone is selected to be Rex it fully involves the family as preparations are made for the big day, but not this time.

Why few knew has remained a mystery. Rex records have no account of the selection process, which is always secret anyway. Adding to the surprise, John insisted, was that his dad did not even belong to the Rex organization. One old-timer did tell me that he had heard that the original Rex selection that year had had to drop out, but no one knows for sure.

Alton Ochsner, who was born in South Dakota, and whose family was not socially connected locally did not fit the typical profile of Carnival royalty, but he was a hot number in 1948.

In 1942, he had opened the pioneering Ochsner clinic and had already built a national reputation by linking cigarette smoking and lung cancer. He was about as honored as an honored citizen could be. Darwin Fenner, who was Captain of the Rex organization at the time, was very innovative. It would have been consistent with his style to fill the vacancy on the throne with a big name, but one with the civic credentials honored by Rex. In a sense, twenty years before Bacchus, Alton Ochsner may have been Carnival’s first celebrity king.

Whatever the circumstances, they certainly changed John Ochsner’s plans. A day in which he was supposed to be hanging with friends to celebrate his own big moment ended with his being all dressed up at the Rex ball.

John Ochsner would become a distinguished physician himself specializing in transplants, including the lung but most of all, the heart. Ochsner hospital became one of the leading transplant centers in the country.

In 1990 a limousine would again arrive at an Ochsner household, this time to pick up John, who would reign as Rex that day. (With the full knowledge of the family.)

Although he would only wear one crown, John Ochsner would serve two kingdoms; Carnival and the hospital where staff referred to his as “The King of Hearts.”

MUSES AND MOOSES

Above is a story about the origin of the Krewe of Muses. Now, hold on tight. Time passes. Here’s a story from Krewe founder Stacie Rosenberg talking about the impact of the krewe from the perspective of a young girl who had known of Muses all her life:

“When Muses was 11 years old, the 11-year-old daughter of a lawyer in my office was visiting on a Saturday. When I saw her, she ran over and said, ‘Me and my friends were talking and we thought if there was ever a parade just for boys it should be called Mooses.’ I love this story because this little girl did not even realize that there were any parades ‘just for boys,’ but for her entire existence she knew there had been a parade just for girls. I also love that she wanted to call boys mooses!”

Well, at least the truck parade is run by the Elks Club.

Perry Swearingen Young was a journalist in New Orleans during the 1920s and ‘30s. He was a gifted writer who produced a local classic, “The Mistick Krewe: Chronicles of Comus and His Kin,” probably the most important book ever written about the origins of the early Carnival. This year marks the 90th anniversary of that book receiving its copyright, 1931. All research about the season properly begins with a reading of the book. It is from its preface that the “Butterfly of Winter” paragraph that opened this feature is taken.

Young was born in Abilene, Texas. As an adult, he moved to New Orleans where he inaugurated a magazine called “Gulf Ports.” He would also open his own business, Carnival Press, the name under which he wrote, edited and published Carnival programs. Both “World Port” and Carnival Press were operated out of the same office at 520 Whitney Bank Building, a spot which became the informal cradle of Carnival history. There are many gaps to Young’s story, but it might be supposed that in writing about ports, and in being named public relations agent for the Dock Board, his circle included many of the city’s prominent citizens, some of whom were part of the social side of Carnival. Young had contacts in the Comus organization to the extent that he wrote the krewe’s programs. His best offer came when he was asked by the Captain of Comus, Sylvester P. Walmsley, to do a history of the Mistick Krewe – the group that founded and maintained the New Orleans parading tradition. The book was to be prepared as a krewe gift to celebrate the group’s 75th anniversary in 1932. But then Young’s career took a turn. Walmsley had died and the Interim Comus captain had decided against the book. These were also hard times in the real world, as the glitter of Carnival was paled by the Depression. “World Port” magazine was moved to California, leaving its editor behind. Young maintained Carnival Press and also began publishing two other magazines, “Shore” and “Beach and Garden.” But the income was not steady.

His daughter, Zuma Young Salaun, once recalled that there was financial uneasiness during that time, but that her father was too proud to discuss his problems at home. “My mother wanted him to find a job like a streetcar driver,” she remembered, “but he wasn’t very mechanical, he would have wrecked the streetcar.” Instead, the writer in him tried to prevail, churning out house organs and writing Carnival publications. Young was learned in the classics, mythology and foreign languages, making him the right reporter to break through the lore from which Carnival grew. He wrote with a scholar’s familiarity of the poet Ovid’s description of the early pagan rites of spring. He collected engravings of early parades and listed those long-forgotten who wore the crowns. His was a journal of New Orleans society written and presented in a style to embellish the grandest of reading room coffee tables. Young died in 1939 at the age of 51. Only about 1,000 copies of his book had been distributed. In a warehouse, his daughter located approximately 9,000 unbound copies, from which she was able to distribute some of the engravings. Eventually, the remaining stock was sold for wastepaper. Young was one of those writers who never fully knew his success. “The Mistick Krewe” remains timeless, although he died without reaping any profit from the book, nor likely realizing its importance. In 1969, Zuma Young Salaun allowed the book to be reprinted. She had become a Carnival historian on her own, giving lectures, writing pamphlets, and remembering her father.

After his death, Perry Young was eulogized not so much as an historian, but as a conservationist. Of his writings in “Shore and Beach,” for example, it was said that, “the cause of shore protection lost a valiant and gallant advocate…who did not strive for wealth.” But Perry Young’s memory has been preserved by Mardi Gras, and he will forever be remembered each winter for his book that is so enriched by its opening lines. Many seasons have passed since Perry Young completed The Mistick Krewe. Now there is a new generation of writers covering Carnival, any one of whom would be fortunate to one day look at the spectacle and see a butterfly.

Errol Laborde: Mardi Gras, Chronicles of the New Orleans Carnival

MATTERS OF THE HEART

If all hearts are created equal, why are minority populations at such a higher risk?

BY TOPHER DANIEL

In the early days of the pandemic, an unsettling trend began to emerge, one that has endured and been magnified as COVID-19 cases continue to rise: minorities in the United States, specifically Black, Latino and Indigenous populations, are far more likely to die following infection.

According to the APM Research Lab, Indigenous people are approximately 3.3 times more likely to die from COVID-19 than non-Hispanic White populations, while both Latino and Black populations are 2.7 times more likely to die. These trends, while thrown into harsh light since the United States saw its first surge of coronavirus infections in March 2020, are nothing new.

Health disparities between minority and White populations have existed for decades, and the causes are deeply entangled in longstanding social and economic divides that put certain populations at a substantially higher risk for life-threatening conditions.

Prominent among the health issues disproportionately affecting minority populations - and contributing to elevated mortality rates - are matters of the heart, such as cardiovascular disease and hypertension. The Office of Minority Health, a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, reports that Black Americans are 40 percent more likely to have high blood pressure than non-Hispanic White Americans and are 20 percent more likely to die from heart disease. Despite that, only 44.6 percent of Black adults with hypertension are likely to have their blood pressure under control, as opposed to 50.8 percent of their White counterparts.

In light of this data, the question is no longer whether disparities exist; they do, and they’re illustrated in our society more clearly than ever. The question is why do they exist, why do they endure through generations and, ultimately, how do we stop the cycle?

PHYSICAL AND SOCIAL INEQUITIES The American Heart Association identifies seven factors that make up an individual’s cardiovascular health, known as “Life’s Simple 7”: smoking status, BMI, diet, cholesterol, physical activity, blood pressure and blood glucose. In theory, maintaining ideal levels of all seven factors will decrease an individual’s risk for developing cardiovascular disease or suffering from early mortality.

But in a 2018 edition of “The Journal of the American Heart Association,” Dr. Eduardo Sanchez published, “Life’s Simple 7: Vital But Not Easy,” in which he states that, “Items easy to list are not as easy to achieve...It will likely take individual and socioecological (population-level) efforts to achieve and maintain high [cardiovascular health].”

Dr. Nicole Redmond, a medical officer with the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, has dedicated her career to advancing research that addresses health disparities across racial and ethnic lines. The complexity of the issue, she says, arises when evaluating the extent to which physical and social determinants allow minority populations to engage in activities that promote cardiovascular health.

“No one is born with cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Redmond said. “You’re born in normal health, and your environment starts to determine the evolution of your cardiovascular health over time. We see evidence that Black Americans accumulate risk factors like obesity and hypertension earlier in life and at higher levels.”

First, there are physical factors, such as the neighborhood and environment in which a person is raised, their proximity and access to healthy food options and, if those resources aren’t located in walking distance, the availability of transportation to reach them.

“There’s also been a lot of attention on how our housing policies have created ongoing neighborhood segregation and disinvestment in neighborhood resources,” Dr. Remond said. “It’s one thing to say we know physical activity is important for heart health, but how accessible is physical activity for people who don’t feel safe going for walks, or who live in neighborhoods without sidewalks? And if they have to walk somewhere to get groceries, but the only thing they can reasonably walk to is a convenience store, their food options will be limited. All these things are related.”

Additionally, Dr. Remond says these determinants must be considered minority, and specifically as a Black American. Even as a physician, these alongside income and poverty, which “impacts your ability to attain health- are things I didn’t spend time thinking about. But I do now.” promoting resources” that not only include healthy foods, transportation and safe neighborhoods, but subsequently, education and healthcare. AWARENESS AND ACTION

To put this in perspective for New Orleans, unaddressed repercussions It has taken years of inequality - and stagnation in addressing it - to of redlining, a practice which systematically denied funding and services reach a point where the hearts, bodies and minds of minorities are at a to neighborhoods with a majority of Black residents, continue to put distinct disadvantage. In turn, it will take years of work to undo it, and Black citizens at financial and environmental disadvantages. Based on data there are many dominoes that must fall if the health gap and all related compiled by American Community Survey, The Data Center (formerly racial divides will ever be mended. known as Greater New Orleans Community Data Center) reports that “It can be overwhelming when you think about how deep this runs, median income for Black households in New Orleans is $24,813, compared but it’s important that we first have awareness as a community,” Dr. to $69,852 among White households. That puts Black households at a 32 Singleton said. percent poverty rate, and White households at 10.3 percent. Part of that awareness means acknowledging that inequities in health

And while redlining was formally ended by 1968’s Fair Housing and access to care can exist on both macro and micro scales, across Act, The Data Center’s 2018 report, “Rigging the Real Estate Market: states, cities, neighborhoods and streets. The New Orleans chapter of Segregation, Inequality, and Disaster Risk,” details the ways in which Black the American Heart Association reports that “a person living in the zip New Orleanians continue to dwell in underdeveloped neighborhoods code 70112 is five times more likely to die from heart disease than those with fewer resources and lower levels of elevation, where they are more living in the neighboring zip code 70113.” vulnerable to natural disaster, as a result of the economic divide created Another, more critical part, is that once your awareness of an issue has by decades of disenfranchisement and racial segregation. been raised, Dr. Singleton says it’s important not to look away, no matter

“Factor in living on the coast, where a hurricane can affect infrastructure, how uncomfortable it may be. That’s especially true for higher-income, transportation, power grids, food and clean water, you start to see all non-minority households--because no matter how aware a minority these differential health impacts on a larger scale,” household is of health disparities, that doesn’t give them Dr. Redmond said. access to healthy foods, healthcare or geographical equity.

In light of how these disparate circumstances fall along Those who have benefited from and perpetuated such racial lines, the physical factors required to maintain cardiovascular health using the “Life’s Simple 7” model become all the more difficult for minorities to achieve. And then there are the social factors which, when compounded with the physical determinants, further widen the health gap minorities must overcome. Dr. Tammuella Singleton is a pediatric oncologist who practices in both New Orleans and Slidell, and she describes how social determinants such as stress - which in the case of minorities is fueled by racial bias, microaggressions and discrimination - can lead to poor cardiovascular health. Both she and Dr. Redmond relate this chain of causality to the “fight No one is born with cardiovascular disease.You’re born in normal health, and your environment starts to determine the evolution of your cardiovascular health over time. divides - even unknowingly - must be part of the solution, at both the individual and community levels. “A great place to start would be to connect with your local American Heart Association,” Dr. Singleton said. “Find out what programs are having a significant impact in our local communities, where you can see what’s happening. Maybe you can help to provide additional healthy foods at Second Harvest, or support organizations like Liberty Kitchen. That’s something you don’t have to go far to accomplish. Everyone can find something, some way, to get involved.” In New Orleans, ongoing initiatives at the American Heart Association include the establishment of safe or flight” survival response. spaces for minorities to engage in physical activity, in

“When you’re stressed, your heart rate goes up. Your addition to providing healthy foods and addressing blood pressure climbs a little higher. Your cholesterol levels increase, and affordability. Meanwhile, local organizations like Heart N Hands are you probably eat more and retain a little more fat,” Dr. Singleton said. actively engaging young girls--a minority demographic itself--in fitness “Self-preservation is the first law of nature, but that fight or flight response and wellness activities. In 2020 alone, Heart N Hands provided more than was only designed to be there when we needed it. From a biological or 400 schoolchildren with fresh fruit in a collaborative effort with No Kid physiological standpoint, it was never meant to exist indefinitely, for Hungry and hosted an in-person and virtual “Running for the HEART” days, weeks, months or years on end. Stress is a significant contributor to 5K to both fundraise and stimulate physical engagement. Supporting heart disease, and when you compound that with poor dietary options, any such organizations through donations or voluntarism could yield a lack of daily exercise, and add them to the stress of just being a Black tremendous effects in helping to expand their reach and impact. American, now you have a recipe for disaster.” While there’s a long road ahead, with many more disparities to address

Dr. Singleton notes that many of these stress-inducing social factors along the way, taking that first step on an individual level can begin the might begin to affect a person’s health before they even realize they’re process of incremental - and eventually, monumental - change. experiencing them. For reference, she describes her first experience at “New Orleans has a heart and a soul, and it has a large Black populaXavier University, an HBCU, after receiving early and secondary education tion,” said Dr. Singleton. “We need to partner together and focus on all at public schools where she was a minority. angles to figure out how we can all live better lives in our city and our

“It was a release,” she said. “It was like I exhaled. All this time, I didn’t state. It starts with awareness and attention. It’s going to require some even know I was under this pressure, but for the first time, I knew that if difficult and uncomfortable conversations, but if we are thoughtful and one of my peers didn’t like me, they just didn’t like me. It wasn’t because I deliberate in what we do, we can still change the quality of life for these was Black. These are stresses accumulated just existing in the world as a individuals and allow them to make a significant impact on their health.”

f your physical health has commanded most of the spotlight recently, it might be time for a financial checkup. That is especially true after a year filled with unanticipated shocks – economic and otherwise.

We asked a panel of experts what good financial planning looks like at various life stages, from workforce newbie to retirement ready and everything in between.

Just starting out

According to the experts, it’s never too early to establish good financial habits. “They’re like muscles,” Ferro said. “If you keep using them, they will just get bigger and stronger through the years.”

No surprise here – all the experts agree on the most important habit: saving, then saving some more. For many people, the pandemic offered a painful lesson in the value of an emergency fund. “It’s like the levee system in New Orleans,” Ferro said. “That is for protection against storm surges, and this is a financial surge.”

This emergency fund should be safe, but accessible. Ferro suggests a money market or bank account: “It’s plain vanilla – not exciting, but very important.”

Once an emergency fund is established, the next step is building a long-term investment program. According to Mark Rosa, President and CEO of Jefferson Financial Federal Credit Union, a brokerage account offers the most reliable path to accumulating wealth. He suggests options like mutual funds for growth that outpaces the rate of inflation, something young investors don’t always consider when they begin socking away money for the long term.

Though new savers may perceive investing as risky business, financial planners emphasize the fact that financial markets have weathered decades of crashes, recessions and pandemics, while continuing to rebound and grow.

“You want to be positioned to have your foot in the door,” Ferro said. “Accept that there are setbacks, but the setbacks are temporary. The movement forward has always won.”

Early professional life often carries start-up costs, including debt from school loans, upgrading a car, or investing in a workplace wardrobe. The goal, Rosa advised, is for workers to eventually transition to a career stage where that debt dynamic flips and “the choo-choo is running up the track.” Employees might get promoted, pay off school loans and contribute to their company’s 401k plan. Along the way, Rosa encourages people to “save until it hurts.”

He also suggests putting off major life transitions, like parenthood, until a financial cushion is in place. “Those first couple of fragile years when you’re taking on more debt, I see people feel pressure to get married, start a family… It doesn’t permit them to start saving and build that cushion if they move too quickly in those other directions.”

Growing your family

It’s never too soon to start saving for higher education. “The child is born, and you’re starting a college savings account,” said Shelley Ferro. “If you do it then, you’re going to be fine. If you wait too long, you can’t get the compounding effect of money to work for you.”

Ferro recommends the Louisiana START savings program, a state-administered program that allows families to save for higher education with a tax-deductible benefit. The state commits to match a portion of that savings on a sliding scale based on the family’s income, with lower incomes receiving higher percentages.

New parents also need to address other provisions for their children, like establishing guardians and securing life insurance. These considerations are especially important for single parents. “Things like an emergency fund and life insurance become even more important when you’re single because you just don’t have anybody to fall back on,” Ferro said.

Buying a home

The turbulence of 2020 has also affected expert advice for prospective homebuyers. Drew Remson, President and Owner of America’s Mortgage Resource, Inc., now cautions buyers to take a more conservative approach. “Historically, first-time homebuyers come in, and the first thing they ask is ‘How much do I qualify for?’” Remson said. “They want to know the max, and they shop the max.”

Remson warns that this period of unexpected income changes is not a time to be “house poor.” Buyers should make their decisions based upon only stable income, rather than components like overtime or commission. He also encourages dual income families to take the conservative approach of qualifying on one income, which would protect their investment in the event that the other disappears.

Because a savings cushion is so important today, Remson has also amended his typical recommendation for a sizable (e.g., 20 percent) down payment. “In this environment it may make sense for folks to put less down and have more in reserve,” he said. “Move forward with some money in the bank rather than being in a better position on a monthly basis but having no money in the bank after closing.”

Interest rates remain historically low, a trend Remson expects to continue through 2021. “From an interest rate standpoint, it’s an absolutely ideal time for people to get into the market that don’t own a home now,” he said. “Your buying capacity is so much higher at a 2.5 percent rate than it will be at a four or five percent rate.”

Above all, Remson advises firsttime homebuyers to work with a professional who can guide them through the process and the various programs available.

Readying for retirement

When it comes to retirement planning, many people focus on a magic savings “number” that will allow them to retire with security. According to Mara Force, Professor of Practice at Tulane’s A.B. Freeman School of Business and retired Managing Director, J.P. Morgan Private Client Trust, “What you’re seeing now is a lot of people who don’t quite retire because finding that number is elusive.”

Several factors play into the equation, like the age at which someone wants to stop working and their plans for healthcare coverage. “If you’re not yet old enough for Medicare when you retire and have to cover your healthcare, that’s going to be a really big cost,” Force said.

Force also reminds retirees-in-waiting to account for property taxes, which stick around even after a mortgage is paid off, as well as any taxes they will owe once they begin taking distributions from 401k accounts.

People who haven’t been able to reach their savings goal by retirement age often pick up secondary careers or “side hustles.” Those can be helpful for retirees who miss the routine, stimulation or other aspects of their former career. “There are a lot of people who retire and then quickly unretire because they say, ‘Oh my god, I’m bored out of my mind,’” Force said.

As retirement nears, people should evaluate the riskiness of their investment assets and reduce volatility in their portfolio. “You want to make sure you’re not putting your retirement at risk by investing in something that’s too potentially risky,” Force said.

Mark Rosa advises people to use time to their advantage when saving for retirement – and not wait too long to start putting away money. “You’re not going to get from age 55 to 60 with any growth capability,” he said. “Then you’re relying on the Social Security process, anything you’ve accumulated at work and in savings accounts. It’s not a strong financial position.”

For people approaching retirement with a mortgage, Drew Remson advises them to refinance while they’re still employed. “If you’ve got a mortgage out there, you can cut your long-term payments by refinancing,” he said.

Given current low interest rates, retirees might also opt to borrow against the value of their home through a reverse mortgage. Remson believes there is a lot of misinformation out there about reverse mortgages, but he finds them to be a good answer for certain clients. “It is the right product for a lot of people to age in place and be able to stay in their home for their lifetime without having to sell their property and downsize significantly to survive.”

Estate planning

Through a career spent working with high-net-worth clients and their beneficiaries, Mara Force has seen the full gamut of estate planning (including trusts for pets). According to Force, many people set up trusts because they want to ensure that their offspring are cared for and won’t “go off the rails,” to have their basic needs met in a tax-efficient way or to provide for certain types of enrichment or philanthropic activity.

Trusts are often created to fund children’s education or with plans for legacy building that will involve heirs in philanthropy. Force suggests people set up a donor advise fund, which can be done with a relatively small amount of money, for grandchildren or others to administer and provide recommendations for charitable giving after the donor’s death. “The money has to go to charity, but those whom you designate can recommend the charity to which it goes,” Force said. “That will cause them to be engaged in philanthropy, and your money will continue to give and give and give until it runs out, as opposed to just one gift upon your death.”

Force also reminds people to think about where their investments are sitting to minimize any tax burden for their heirs. “You can designate that the money you would give to charity come out of an IRA or 401k plan, and money that you had free and clear [already taxed] in a checking account goes to your kids.”

Pandemic takeaways for every stage

The COVID era has led Mark Rosa to move from a one-size-fits-all recommendation for savings to a more job-specific approach. “If your job is waiting tables, there’s nothing wrong with that, but it’s fragile to downturns,” he said. “You might need more savings than most folks. if your job is medically related, those people have been employed eight days a week, so they could have money flowing out of their pockets.” Rosa adds that people working jobs with no benefits or retirement plans should try to build a sizable savings stash – as much as twelve to eighteen months of net income.

Shelley Ferro encourages everyone, especially young people, to have an accurate handle on their expenses and income. “It seems basic, but you’d be surprised at the number of people who just don’t do it,” Ferro said. “I knew a 90-year-old woman who had literally millions of dollars, and she was really scared she was going to run out of money. I was like, ‘It’s mathematically impossible. You can worry about other things, but not that.’”

That example shows the role of psychology in a person’s financial health, a subject known as behavioral finance. Ferro focuses on this dynamic in her work as a money coach. “What I’ve seen in my career is that so much of what goes on is behavior that’s based on beliefs,” she said. “If you can work with someone to help them uncover that, then they have the ability to change that behavior and create a more peaceful state with their finances.”

As we emerge from a time of uncertainty, there is little doubt that the pandemic era will leave lasting financial impressions on people across careers and life stages. For everyone, Ferro offers some timeless advice: “Life is what it is. Enjoy the happy times and prepare yourself for the times that are more challenging.”

Eight Common Money Missteps 1

Racking up credit card debt

“The biggest mistake people make is when you’re just starting out and you get your first credit card,” said Mara Force. “You’re so excited, and you impulse buy things you shouldn’t and rack up early debt on stuff you just didn’t need to own.”

2

Neglecting the snail mail

Force sees this trend among younger people. “This can be a really big problem if someone is sending you a bill and you don’t pay it – it can really damage your credit,” she said. “People should remember to open their mail and at least glance at it before throwing it out. I admit opening bills is not my favorite thing to do, especially when we are so used to paying things online, but once a week you’ve got to bite the bullet and do it.”

3

Not questioning fees

“If you have a financial advisor, when you go to a bank, get a mortgage, ask somebody ‘How much am I paying for this?’” said Force. “Because a lot of times fees are deducted from places you wouldn’t notice or called something that doesn’t scream ‘fee.’ Ask: ‘How much are you charging for this? What are your rates? is this market standard?’ Know how much you’re paying for something and feel like you’re getting the value for what you’re paying.”

4 6

Missing out on refinancing opportunities

“Right now, the first and foremost mistake people make is not taking the time to refinance if it makes sense,” said Drew Remson. With today’s low interest rates, many people could secure a rate that would allow them to decrease their interest payments over the life of a loan by nearly fifty percent. “On a $200k-plus loan, we’re talking about hundreds of thousands of dollars over the life of a loan,” he said.

Remson also sees people missing out on refinancing because they have taken mortgage payment deferments, now easily obtainable from most lenders servicing a loan. “One of the mistakes I see is people taking them that don’t need it, and then they can’t get a refinance because they took the deferment,” he said. “The rules on deferment state that you have to be out of deferment and make at least three payments after you come out before you’re eligible for a Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac-type loan, so people are getting frustrated that they are in deferment and can’t refinance.”

Investing prematurely in retirement

Shelley Ferro doesn’t like to see people putting retirement savings ahead of more pressing needs. “It doesn’t help to contribute to retirement if you have no savings and then you run into problems and you’ve got to go to your retirement,” she said. “It’s all got to be done when you’re financially ready. I don’t like when people jump the gun. I’ve seen on more than one occasion couples who have started to save in 401k but don’t have any money saved up – for anything.”

7

Not paying off the monthly credit card balance

Mark Rosa is discouraged to see people “getting creamed” by keeping a balance on a credit card. “You never get a reprieve,” he said. “That’s the downside to credit – getting ahead of yourself and not paying attention.”

8

Underestimating the task of building wealth

Mara Force knows it can be challenging to accumulate wealth and wants to encourage empathy. “Some people think it’s easy and America is the land of opportunity, but it’s hard, and not everyone gets to start from the same place,” she said. “People often think those who don’t have savings have done something wrong or didn’t work hard, but it’s a bigger issue. A significant percentage of the population just doesn’t have the type of income to allow them to have savings. That’s not because they’re not trying but because we have some significant gaps between rich and poor in this country. If someone is making enough to subsist, you can’t ask them to be saving for retirement and then telling them they’re lazy if don’t save enough. That said, I would also tell us to take a life lesson from 2020 and not buy a bunch of needless, worthless crap. The things are not going to fill the emotional void in the way we want them to, so don’t waste the money.”

5

Using the wrong financial advisor

Ferro points out the difference between advisors selling products and fiduciary advisors, who, like attorneys and CPAs, are legally obligated to look out for the client’s best interest. “A fiduciary is in a process-driven relationship with clients, whereas people on the sales side are in a productdriven relationship where they are trying to sell products in the best interest of a corporation.” She encourages people to understand these distinctions when choosing an advisor and to consider that different advisors may be appropriate for different life stages.

Ferro also disputes the notion that financial advisors are only for wealthy people. She recommends Garrett Planning Network, which offers advisory services on an hourly basis, to people beginning their search for financial planning guidance. To people hesitant to spend hard-earned money on advice, she says, “If you have to spend a couple of hundred dollars to ask someone a question, it’s probably worth it if it’s going to save you the cost of a mistake or non-action in the long run.”