30 minute read

Publikuar nga: Publikuar nga: THE CASTLE: HOW SERBIA’S RULERS MANIPULATE MINDS AND THE PEOPLE PAY

from Gazeta Reporter.al

by Reporter.al

INVESTIGATION

The Castle: How Serbia’s Rulers Manipulate Minds and the People Pay

Advertisement

Serbian taxpayers are unwittingly paying for an army of bots to promote the country’s ruling party and denigrate its rivals.

ANDJELA MILIVOJEVIC | BIRN | BELGRADE

His Twitter name is ‘Robin Xud’, a Serbian homage to the legendary English outlaw hero who robbed from the rich and gave to the poor.

And just like the Sheriff of Nottingham in the ballads of Robin Hood, Xud’s enemy resides in a castle, in this case an Internet database registered in 2017 at www.castle. rs Staring into two monitors in a dimly-lit room, Xud – who spoke on condition BIRN did not reveal his true identity – is part of a small team of programmers tracking the online operations of Serbia’s ruling Serbian Progressive Party, SNS.

According to Xud’s band of merry men and the findings of a BIRN investigation, the Progressives run an army of bots via the ‘Castle’ working to manipulate public opinion in the former Yugoslav republic, where President Aleksandar Vucic, leader of the party, has consolidated power to a degree not seen since the dark days Slobodan Milosevic at the close of the 20th century.

With the help of the programmers, this reporter gained exclusive access to the network for several months in 2019, observing how hundreds of people across Serbia log into the Castle everyday during normal working hours to promote Progressive Party propaganda and disparage opponents, in violation of rules laid down by social network giants like Twitter and Facebook to avoid the coordinated manipulation of opinion.

It is a costly operation, one that the Progressive Party has not reported to Serbia’s Anti-Corruption Agency. But the party doesn’t foot the bill alone.

This investigation reveals that some of those logging into the Castle are employees of state-owned companies, local authorities and even schools, meaning their botting during working hours is ultimately paid for by the Serbian taxpayer.

“Right now, over 1,500 people at least are botting every day,” said Xud. “They sit there in their jobs and instead of working they spit on their people.”

‘This is not activism’

The Progressive Party took power in Serbia in 2012, four years after Vucic split from the ultranationalist Serbian Radical Party and declared himself a changed man who now favours integration with the European Union after years of demonising the West.

As the opposition splintered, the Progressive Party established itself as the dominant political force with Vucic as its strongman. It is widely expected to win handsomely in parliamentary elections on June 21. Serbia’s minister of information during the 1998-99 Kosovo war, when NATO bombed to halt a wave of ethnic cleansing and mass killing in Serbia’s then southern province, Vucic has presided over a steady decline in media freedom since taking power.

Critics find themselves shouted down and pushed to the margins, the most vocal dissenters often targeted for online abuse.

In April this year, the Progressive Party’s online escapades made international headlines when Twitter announced it had taken down 8,558 accounts engaging in “inauthentic coordinated activity” to “promote Serbia’s ruling party and its leader.”

BIRN has reported previously on how some of these accounts made their way into pro-government media, their tweets embedded in articles as the ‘voice of the people’.

This story lifts the lid on the scope of the Progressive Party’s campaign, how it directs the tweets, retweets and ‘likes’ of an army of people and how ordinary Serbs are footing part of the bill. “This is not about activism, where a person writes what he wants or what he believes in,” said Xud. “These people have tasks; it is literally written what they need to criticise and how to criticise”.

The Progressive Party did not respond to questions submitted by BIRN for this story. However, in early April, after the Twitter announcement, Slavisa Micanovic, a member of the party’s main and executive boards, took to the platform to dismiss claims about a “secret Internet team” within the party, saying everything was public and legitimate.

“What exists is the Council for Internet and Social Networks, established in the party congress of 2012 and which can be found in the Statute and deals with promoting the party on the Internet and social networks,” Micanovic tweeted.

Reporting for duty

One August day in 2019 began like this:

At 7.56 a.m., a user named Nada Jankovic logged into the Castle from the town of Negotin, near Serbia’s eastern border with EU members Romania and Bulgaria. “Good

Photo: Unsplash/Mika Baumeister

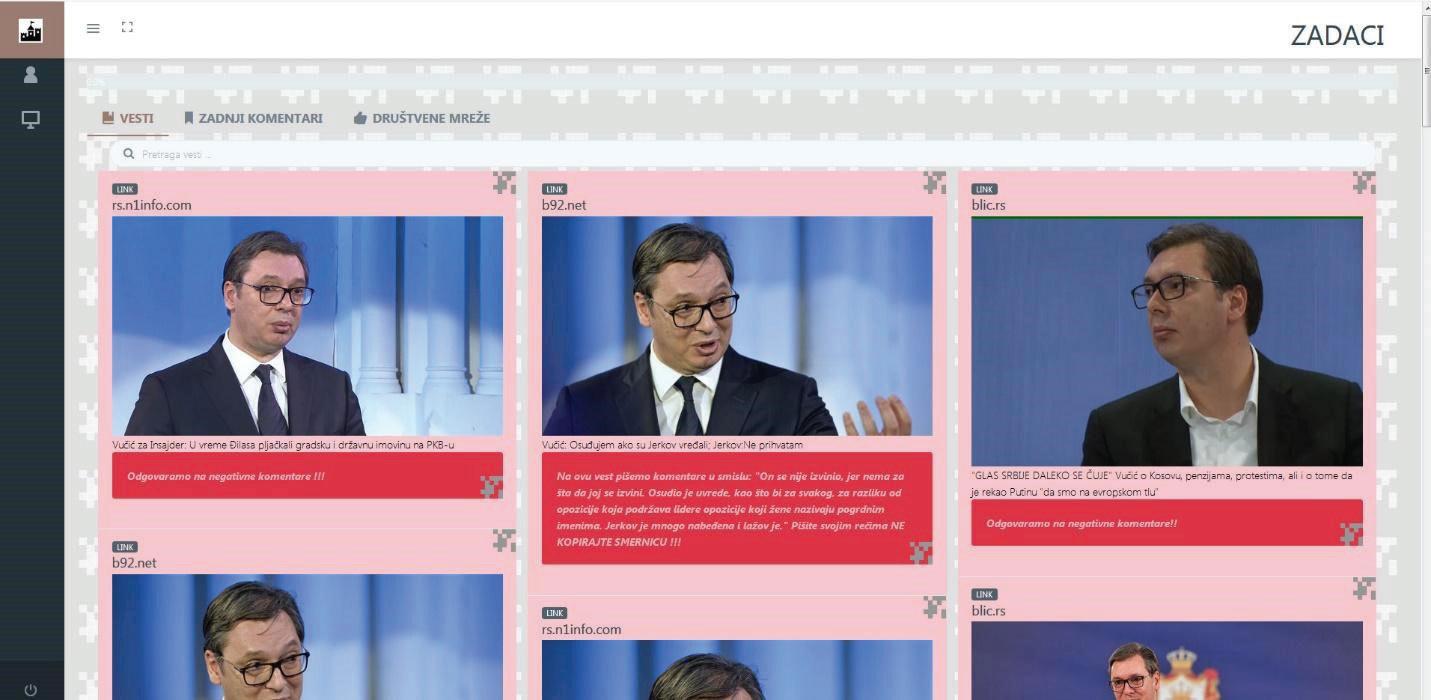

Instruction to defend Vucic. Screenshot: Robin Xud

morning, duty officer,” Jankovic wrote. Minutes later, in Sabac, just west of Belgrade, DusanIlic joined in with the words, “Good morning all”. The bots had reported for duty, each entering the Castle system via a private account.

Xud and his team first accessed the Castle in January 2019 via an account with a weak password.

The Castle, they found, links to all Facebook and Twitter accounts operated by each user – frequently more than one per user – and lists five Twitter profiles they are obliged to follow: the official accounts of the ruling Progressive Party, President Vucic and Interior minister Nebojsa Stefanovic, as well as the accounts of two Progressive Party officials – deputy leader Milenko Jovanova and Micanovic. ‘Daily performance reports’ contain the name of the user, the municipality where they logged in and the extent of their activity on a given day: comments, likes, retweets and shares.

Points are allocated depending on how busy a user has been, though it is not clear whether this translates in rewards. “The system is designed to follow every step the bot takes, from morning to night,” said Xud. “Everything is recorded in the Castle.”

Once logged on, the bots await their instructions.

On August 2, it was to shoot down criticism of Vucic’s appearance the day before on a pro-government private television channel called Pink

Vucic had caused a storm when he read from classified state intelligence documents the names of judges and intelligence officials who he alleged had approved covert surveillance against him between 1995 and 2003, a period when Vucic, then a fierce ultranationalist, was in and out of government.

Critics accused him breaking the law by quoting from classified files.

So the Castle kicked in, with the following instruction:

“When replying to this and similar tweets, use this guideline: According to the Law on Data Secrecy (Article 9), the President of the Republic has the authority to extend the secrecy deadline (Art. 20) and revoke the secrecy seal (Art. 26) if it is in the public interest.”

Days later, on August 5, a picture of Vucic started doing the rounds on Twitter in which he wore sneakers that critics said were worth 500 euros. The Castle turned its sights on his political opponents, Dragan Djilas and VukJeremic; one bot tweeted, “Where did Djilas get half a million euros in his account from?”

In the space of just one day that BIRN monitored, the Castle bots were sent 60 different Twitter posts they were instructed to combat; the majority were posted by opposition leaders Djilas, Jeremic, Bosko Obradovic, Sergej Trifunovic, Dragan Sutanovac, Zoran Zivkovic and VelimirIlic.

The Castle ‘special bots’ in charge of issuing instructions stressed the need to avoid

Illustration. Photo: Unsplash/camilo jimenez

detection; in late January 2019, users received a link to a statement by Vucic in which he condemned insults directed by his former mentor, the firebrand Radical Party leader Vojislav Seselj, at a female MP from the opposition Democratic Party, Aleksandra Jerkov.

The instruction read: “We are writing comments on this news in the sense: He (Vucic) did not apologise, because there is nothing to apologise for. He condemned the insults as he would for anyone, unlike the opposition which supports opposition leaders who call women derogatory names.”

“Write in your own words,” it stressed. “DO NOT COPY THE GUIDELINE!!!”

Botting while at work, on the taxpayer dime

Among those receiving such guidelines is Milos Jovanovic, a former public sector employee in the youth office of the local authority in Cukarica, a municipality of the Serbian capital, Belgrade, but now deputy director of the Gerontology Centre in Belgrade, which helps care for the elderly.

Jovanovic is paid out of state coffers. But according to BIRN monitoring, last year he spent much of his working day logged into the Castle. He declined to comment when contacted by BIRN.

Fellow Castle users are Mirko Osadkovski, employed in the local authority in Zabalj, northern Serbia, as a member of the Commission for Statutory Issues and Normative Acts and a local councillor, and Damir Skrbic, head of the communal services in the municipality of Apatin near the western border with Croatia.

Osadkovski did not reply to emailed questions. Skrbic declined to comment when reached by phone.

But they are not the only ones.

The Castle database contains the names of at least two Progressive Party people elected to the local assemblies of Vrsac, near the Romanian border northeast from Belgrade, and Sabac – Milana Kopil and Nenad Plavic respectively.

Kopil responded that she would not comment for BIRN. “As someone who supports the policies of Aleksandar Vucic, I have absolutely nothing positive to say about BIRN,” Kopil said. Plavic said he would only talk after the June 21 election.

Then there are those employed in public enterprises such as state-owned power utility Elektroprivreda Srbije, and others who work in schools.

In August last year, the Nis-based portal Juznevesti published the ‘testimony’ of an unnamed Progressive Party member and former member of the party’s ‘Internet team’ who said that the bots had been organised by party officials with the intention of creating a false image of public satisfaction with the government. He also said that most of the bots were employed in public companies and risked dismissal if they did not follow orders.

Costly operation

The website http://castle.rs/ was first registered in October 2017. Its ownership has not been visible since the privacy clause for this domain was activated. But there is ample evidence that it is controlled by the Progressive Party, not least the IP address.

According to the IPWHOIS Lookup tool on ultratools.com, the IP address found in the code of a mobile application that existed in Castle, 77.46.148.99, was registered in March 2016 at the same address as the party’s Belgrade headquarters in Palmira Toljatija Street. It is one of eight IP addresses leased by the party, from 77.46.148.96 to 77.46.148.103.

The ultimate owner is Telekom Srbija, a state-owned telecommunications company.

BIRN asked Telekom Srbija how much the Progressive Party pays for use of its static IP addresses and when the lease agreement was made. The company replied:

“Telekom Srbija has a commercial contract with the SNS, just as we have commercial contracts with thousands of other legal entities. We repeat, we cannot disclose the details of contracts with our customers.”

However, Andrej Petrovski, a cyber forensics specialist and Director of Tech at the Belgrade-based SHARE Foundation, which works to advance digital rights, said such an operation “does not come cheap.” “Apart from renting a certain server or buying it and physically keeping and maintaining it – which is the more expensive operation – they also need to buy a domain, a certificate for protection of communication and fixed IP addresses,” Petrovski told BIRN.

“They need administrators who will administer the database and of course there is the cost of the people who work, who are managed through that application.”

Successive Serbian governments have used their hold on power to fill public sector bodies with party loyalists, and the Progressives are no different.

Petrovski said he doubted any other political party had the resources to mount a similar operation on such a scale.

“At the moment, I don’t think any other political party has the money to invest in something like this or is big enough to have an efficient system,” he said. “SNS is proud to have the most activists and to be the largest party in Serbia. It’s logical they are the only ones with the resources and the need for such a tool.”

Hidden costs

Political financing laws in Serbia require parties to report their expenses to the Anti-Corruption Agency, which is tasked with preventing financing abuses. But the Progressive Party’s financial reports since 2013 make no explicit mention of the money spent to create and maintain the Castle system.

“In itself, it is not against the law on financing political activities for a party to buy such software or pay activists to work on it, but it must be recorded in the financial reports,” said Nemanja Nenadic, programme director at the Serbian chapter of Transparency International.

“If it is not recorded financially, then that is a problem.”

“If it was paid for by someone other than the party itself, then it should have been reported as a gift, as a contribution given to the political party by the person who made the payment,” Nenadic told BIRN.

BIRN asked the Anti-Corruption Agency whether the Progressive Party had ever reported such costs. In its response, the Agency cited all obligations a political entity has in terms of reporting its holdings and expenses, but did not comment on the specific case. Mladen Jovanovic, head of the National Coalition for Decentralisation, which promotes civic participation in local politics, said there was a simple explanation for how some of those working on Castle are paid: from state coffers via public sector jobs.

“The flow of money needs to be checked,” said Jovanovic, whose coalition follows the misuse of public money in Serbia. “That’s the task of the prosecution, because we’re talking about corrupt work that damages the budget.”

“That old dream of all totalitarian regimes, that all citizens say what the leader thinks, has been realised in virtual time by creating in essence virtual citizens.”

On the receiving end

Like any other political party, the Progressive Party does not deny promoting itself on social media, but says its ‘Internet team’ is made up of party activists no different from those canvassing for support on the streets. But BIRN’s analysis of the Castle database shows that the bots do not stop at promoting the party; they frequently target public figures, including journalists and NGO activists.

Zoran Gavrilovic, a researcher for the think-tank Bureau for Social Research, BIRODI, experienced this first hand after he appeared on television to discuss his findings with regards the ruling party’s dominance of the media landscape in Serbia.

Facing a string of insults and threats via Twitter, Gavrilovic responded with the tweet: “A bot is a person who, of free will or due to blackmail, abuses the right to free speech in online and offline space. Botting is a corrupt form of behaviour directed against the public, governance, freedom of speech and the rights of citizens.”

Speaking to BIRN, Gavrilovic said lawmakers should act to rein in such behaviour.

“I look at it as like the para-military formations of the 1990s [during the Yugoslav wars]. There’s no public debate. You are simply an enemy who should be spat on and kicked immediately. It is a para-political organisation.”

The Castle, however, is not the Progressive Party’s first attempt at manipulating public opinion in Serbia via social media.

In 2014, Xud and his fellow programmers uncovered an application called ‘Valter’, after the popular 1972 Yugoslav film about Partisan resistance fighters, Walter Defends Sarajevo.

Unlike the Castle, which works via the Internet, Valter was installed on the home computers of activists and members of the Progressive Party’s Internet team.

Valter was eventually replaced by Fortress, but when the Serbian portal Teleprompter reported on its existence in April 2015 hackers managed to take down the text and eventually the entire site, which no longer exists. Teleprompter no longer exists.

While the Progressive Party did not respond to a request for comment on this story, Vucic did hit back when Twitter took down the almost 9,000 accounts it accused of “inauthentic coordinated activity” to promote him and his party.

“I’ve no idea what it’s all about, nor does it interest me,” he told a news conference on April 2. “I’ve never heard that anyone on Twitter ever had anything positive to say about me.”

Such denials ring hollow for people like Xud. “People have to know that something like this exists,” he said.

FEATURE

While many in the Balkans are behaving as if they are already post-coronavirus, North Macedonia has spent the first days of June under renewed lockdown.

AMER BAHTIJAR, ARBISA SHEFKIU, BORA BOJAJ, CONSTANTIN DANIEL ZUZEAC, KENAN MIMIDINOSKI, MARA SIMAT TOMASIK, MARCEL LEKAJ, SHKELQIM XHAQKAJ, SUZANA NIKOLIC, TANJAVUJISIC AND ZELJKO LAZAREVIC | BIRN |

Serbia has lifted its state of emergency, Montenegro has declared itself coronavirus-free (but COVID 19 returned three weeks after) and a host of others in the Balkan region have relaxed strict restrictions imposed weeks earlier to fight the spread of COVID-19. Yet much of North Macedonia spent the first weekend of June under lockdown following a new spike in infections.

One of the areas was Kumanovo, a town of some 110,000 people that was the first in North Macedonia to introduce a weekend curfew back in early April, a move the rest of the country eventually followed.

Yet in late April, when BIRN visited, parks in the town were crowded, only some people wore face masks and hardly anyone appeared to be social distancing.

The town’s mayor was among reported COVID-19 cases, as was an alarming number of staff at the local hospital. In just one month, at least 75 hospital employees were infected.

“We cannot know for everyone how they got infected,” said Dr. Snezana Zaharieva, the head of the hospital. “Some were in contact at home, some with people with no symptoms, some were treating patients who did not know they were carrying it,” she told BIRN.

People in Southeast Europe have been subjected to a dizzying array of lockdown measures in the age of COVID-19, varying not just between countries but within them and, on occasion, within cities. Common to all was the panic-buying that would follow quarantine announcements, whether in Kumanovo in North Macedonia, Kosovo’s Mitrovica or the Adriatic island of Murter in Croatia.

Checkpoints, police and army on the streets, men and women clad in white disinfecting public spaces – the picture was similar whether in Romanian Suceava, the Bosnian hamlet of Peskiri or Debar in North Macedonia. The 2,000 residents of Murter were told not even to venture into their own backyards, such was the fear of the unknown.

Government measures frequently appeared ad hoc, sometimes poorly planned. On occasion they changed in the face of public criticism. Complaining farmers would get permission to work in their fields, then the families of disabled people would protest and win a reprieve to go outside too. Through it all, the lockdowns, the anxiety and uncertainty, many people have shown a remarkable degree of understanding, or at least have been only mildly critical. Which measures were right and which were wrong, which were premature and which came too late, which were justified and which were disproportionate? It’s hard to say. But what did it look like on the ground? BIRN talked to dozens of people in 12 towns and villages across six Balkan countries to find out.

Tuzi’s total lockdown

Unlike North Macedonia, Montenegro says it has beaten the coronavirus. Residents of Tuzi, 10 kilometres from the Montenegrin capital Podgorica, however, paid a heavy price, with the most severe measures in the region.

After 14 confirmed cases of COVID-19 in one day, the town of some 15,000 people – mainly ethnic Albanians – was put under complete lockdown on March 24. Residents were barred from leaving their homes at any time of day for almost a month, with the only exceptions being authorised volunteers, journalists and, later, farmers. “It was a big drama in general, because people thought there were other reasons these measures were taken, different theories,” said student Donika Berishaj.

“As we know, Tuzi had a large number of cases of infected patients in one day, out of nowhere. If these measures hadn’t been taken the number of infected people would have been bigger because we’re all close to each other.” Each part of the town had its own designated volunteers delivering food and essentials. But the sense of powerlessness took a psychological toll. “To be honest, I’ve been thinking and comparing our lives to those of our family and friends who emigrate,” said local teacher Maja Gojcaj. “They go to a different place with a different culture, into something new, where they perhaps don’t have the chance to make a difference. We’ve found ourselves in the same situation – in our own place but facing a situation in which we can’t make a difference, only adapt to the situation.”

Adapting also meant improvising with homeschooling, first with simple online tools before classes began being broadcast on television in Albanian as well as Montenegrin. Catholics and Muslims could follow weekly religious services on local TV Boin. Farmers might have been at an advantage, with permission to work their fields, but they lacked the labourers

Control spot in Peskiri, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Photo: BIRN/Zeljko Lazarevic

who usually come from neighbouring Albania.

“Now that the borders are closed, we don’t have people to work the land,” said Tuzi farmer Agron Nicaj. After 20 days, the total lockdown was replaced by a curfew, with markets, pharmacies and petrol stations allowed to reopen. One person per household was permitted to do the shopping. Eventually, after a full month, the measures were eased to conform to the rest of the country, where there was no quarantine and now no more cases of coronavirus.

The Bosnian Wuhan that wasn’t

Unlike Montenegro’s Tuzi, Konjic was placed into quarantine long after the town of 25,000 people on the river Neretva emerged as the centre of the COVID-19 outbreak in Bosnia. It all started in the Igman ammunitions factory, where some 180 people gathered in early March to celebrate its 70th anniversary. Soon after, 28 Konjic residents tested positive for COVID-19. Two people died, and others are believed to have spread the novel coronavirus to other parts of the country.

Some Bosnian media reports branded Konjic Bosnia’s Wuhan, in reference to the city in China were the virus first emerged.

“At that moment, everyone looked at the city and its residents like they used to look at those suffering from the plague,” said Konjic epidemiologist Edin Alejbegovic. Konjic was not locked down immediately, however, but almost a month after the Igman anniversary party. The rest of the Herzegovina Neretva canton followed suit, with residents barred from leaving their municipalities and the under-18s and over-65s ordered to stay indoors at all times. In Mostar, Zdenko Bubas missed his walks. Since retiring, Bubas had taken a walk every morning and evening, without fail, until COVID-19 struck. And while Bubas was not allowed to leave his home due to his age, entry to the city of Mostar was denied to other people in the canton. At the same time, bizarrely, Bosnians from the rest of the country could walk in freely. Mostar was left almost empty, however. Famous for the 16 th Century Old Bridge over the Neretva that was shot to pieces during the 1992-95 war and rebuilt in 2004, Mostar became a ghost town, void of the tourists who usually flock to the bridge from midMarch onwards. “This affected my business 100 per cent,” said Elvis Redzic, standing in the empty garden of his restaurant looking onto the new Old Bridge in mid-April.

“I had the permit to work from March 11 and the measures for cafes and restaurants were imposed on March 15,” he said. “You see how big this garden is? We could sit and work comfortably keeping a metre and a half distance and follow the rules.”

Measures have since been relaxed, but travel restrictions mean the tourism industry in Mostar and elsewhere remains under water

No entry, no exit

At the opposite end of Bosnia, in the self-governing district of Brcko, the 33 residents of the hamlet of Peskiri found themselves cut off from the rest of the world for 20 days in April. Brcko authorities closed off the hamlet after establishing that one resident who tested positive for COVID-19 may have been in contact with others. Police officers monitored the movements of residents. The hamlet has no food market or pharmacy. No one was allowed to enter, even journalists. “They said it wouldn’t last long. Two, three days,” Sanela Zecevic, a Peskiri housewife, told BIRN by phone. “When they brought us the documents justifying the ban, they said it would last 28 days. We asked to leave to buy some groceries. I said that I have a small child. They said the Red Cross would take care of everything.”

Zeljko Pranjic, who comes from Peskiri but wasn’t there when it was placed into quarantine, said no help came for eight days, until he organised aid supplies with the help of the diaspora, the Red Cross and youth centre in Brcko. Teams were sent in to disinfect, spraying not just the road but yards and lawns too.

With the lockdown in place, it took 10 days before one villager suffering from serious coronavirus symptoms was finally tested and admitted to hospital.

“I had to call the police, I was crying, begging, [my husband] was sick, I couldn’t handle

it,” said Ivana Zecevic Pejic. “I said that he was dying and that I would break the curfew. The police told me, ‘Break the curfew and take him to the doctor.’ Her husband recovered.

One town, two lockdowns

In majority-Albanian Kosovo, the legacy of the 1998-99 war has been keenly felt even during the pandemic, with Serb-run municipalities in the north facing conflicting measures imposed from authorities in the Kosovo capital Pristina and in the Serbian capital Belgrade.

The Kosovo government was the first to close schools, and vowed police would intervene if those in the mainly Serb north did not comply. Fortunately, perhaps, Serbia – which does not recognise its former province as independent – followed suit a day later, ordering schools to shut their doors.

But there was confusion over curfews, too.

Serbian and Kosovo authorities had introduced different curfew times, a headache for residents of the north Kosovo town of Mitrovica, which is divided between Serbs in the north and Albanians in the south. The north acts largely as part of the Serbian state. “Restricted movement was not that difficult for me,” said Mitrovica resident Mirjana Nunan, originally from the Serbian town of Prokuplje.

“What bothered me more was the fact I didn’t know which measures to follow. I am, in fact, the type that generally likes to listen to authorities, but in this situation I didn’t know who to listen to as the measures overlapped and, in certain situations, made our everyday lives impossible.”

Some were left confused. Others didn’t seem to care: in north Mitrovica, some residents met in bars in secret. The police did not respond, but the gatherings petered out as the number of confirmed cases grew. In early April, north Mitrovica and its 22,000 residents were quarantined. A curfew initially ran from midday until 6 a.m., driving people to grocery stores and pharmacies in droves. Then the rules changes, with people rationed to 90 minutes per day outside depending on the last digit of their ID number. Stores were opened from early morning until 10 p.m. to avoid crowds.

The over-65s were ‘advised’ to stay at home. Ivana Rakic, founder of the association ‘Support Me’, which gathers more than 100 parents of disabled children and adults, said it has been a particularly difficult time for those families, her own included.

“It’s even difficult to explain to my older children that they cannot go out during the curfew, and it’s extremely difficult to explain to little Elena [who is disabled] that she must put on a mask,” Rakic told BIRN. “She protests, complains about not going out… I also hear from other parents that it is very, very difficult.”

Tellingly, tests for COVID-19 conducted in the mainly Serb north of Kosovo were sent for processing in Serbia, with the exception of those carried out in the detention unit in Mitrovica. Those in need of treatment were either admitted to the hospital in the north or transferred to Serbia. The streets were disinfected several times, as well as pharmacies, public institutions and stores. A supply of disinfectant was made available in the town centre so residents could clean the entrances to their apartment buildings. This won praise from many people, but, to the disappointment of others, took a toll on flowers in communal areas.

Kosovo villages appear abandoned

In other areas of Kosovo, four villages around Prizren in the south and Gjilan/Gnjilane in the east were also under lockdown.

Panic-buying was rife.

“On the first day of quarantine, the largest market in the village looked as if it was the night of Eid,” said Mehmet Ahmetaj, a farmer in the village of Korisha near Prizren, referring to the Muslim religious holiday marking the end of the Ramadan month of fasting.

“There were over 500 people milling around, and this increased the risk of the virus spreading,” he said.

Hajriz Miftari from the village of Vrapcic near Gjilan/Gnjilane said he and his family felt abandoned by the state. “In the beginning we were afraid, but now we’re used to it,” he said.

“We have to thank the doctors, but the municipality does not care much about us. It’s been four weeks that we are isolated in our homes and they have brought us food only once. I don’t know if it was worth 25 euros. They didn’t come to disinfect the village.”

In Korisha, once the panic had subsided, an eerie calm settled on the village; the most action was the organised disinfection of the streets. Police officers were stationed at six different points, checking each and every vehicle entering or exiting the village. There were a couple of boys on rollerblades, a lonely dog barking, birds chirping. The place appeared abandoned. Around 100 Kosovo Albanian refugees were killed in Korisha when NATO mistook the warehouse they were sleeping in for a military target and bombed it. Since the war, many villagers have left in search of work in western Europe, and now send money back to help their families. Tending to some 200 sheep and goats in a meadow above the village of Topanica, the days rarely change for Zyqyfli Morina, alone with his flock and two dogs. He is sometimes visited by wolves after his sheep. The last time Topanica was cut off was during the plague, the ‘black death’ as he called it.

“I have heard from the elderly that the entire village moved out of the settlement and had come out in a place called bunga. They stayed there, for how long I don’t know, but the important thing is that they were isolated from the village,” Morina said. Jahi Mustafa from Lladovo near Gjilan/Gnjilane counts himself lucky that he could work in the fields with a permit from the agriculture ministry. But for others whose land was outside the village were not allowed, creating concern given the seasons wait for no one. “Land and the corn do not care about the virus,” said Mehmet Ahmetaj. “If we don’t plant our land now, what will we harvest when the time comes?”

No Man is an Island

They thought they were escaping COVID-19, when in fact they brought it with them. On a Croatian island, suspicion falls on ‘strangers’.

MARA SIMAT TOMASIK,|BIRN | MURTER

View of towns of Murter and Betina in the Murter island from the Chapel of Saint Roko on the hill above in April 2020. Photo: BIRN/Mara Simat

It could have been the perfect way to sit out a pandemic: on an Adriatic island of a few thousand people, renowned for its sandy beaches and olive oil.

If only everyone hadn’t had the same idea.

“A week before the quarantine was introduced, there were cars queuing, cars with foreign licence plates, some from Zagreb and Rijeka too,” recalled Jure Jerat, a resident of the Croatian island of Murter northwest of Sibenik on the Dalmatian coast.

“People were thinking they would be safe here.”

Entry limited

After a spike in visitor numbers in early March, Murter was the first in Croatia to close bars and restaurants, days before the rest of the country followed suit.

But it was only a matter of time before the island registered its first confirmed case of COVID-19, prompting the local authorities to introduce quarantine.

Only those with residence permits could enter the island; those already there had to stay.

The local mayor urged people to stay at home, and even stay out of their own yards and gardens. Most residents appeared to heed the call, with fear spreading fast. Many elderly residents share homes with their children and grandchildren, increasing the risk from the spread of the novel coronavirus.

Conveniently close to the Kornati archipelago, a national park of dozens of island and islets, Murter is popular not only with residents of the capital, Zagreb, but with Italians, Austrians and Germans too, many of them with properties on the island.

In the main town – which shares its name with the island – the fear was even greater given most of its 2,000 residents shop in the same stores and congregate in the same places.

The petrol station, post office and currency exchange bureaus closed. ATMs ran out of money. As time passed, it became clear that a minimum level of activity had to be allowed, so the petrol station reopened once a week for a couple of hours and ATMs were refilled with cash.

Stonemason Ive Sikic Bazokic shared his suspicion: “As our poet Ive Balara would say, ‘Some strangers brought it’.

On the other side of the island, in Tisno, the measures were less restrictive. Silvija Curic, who runs the Tisno library and reading room, was stuck in Murter, but took her work online.

“I miss the library, I miss people, I miss the smell of books,” Curic told BIRN.

The owners of holiday apartments and bungalows made them available to other locals who needed to self-isolate. Tourism stands to suffer badly.

“My job depends on it,” said Jerat, who owns a restaurant in the Kornati national park.

He admitted great uncertainty over “whether we are going to hire workers or only members of the family will work, and finally if we are going to work at all and how. Will there be tourists or not? Will it be profitable to open it for guests at all? Our most frequent guests in August are Italians. See what’s going on over there? Uncertainty.”

After targeted testing to explore how widespread the virus was on the island, the month-old lockdown on Murter was lifted.

People are still cautious and say they won’t be taking for granted some simple things, as they used to.

But will anything be the same again?