17 minute read

WAITING FOR THEATER CURTAINS TO RISE AGAIN

It’s been a long, dark spring and summer for Atlanta’s theaters. Metro playhouses turned out the lights months ago to slow the spread of Covid-19. Unable to gather audiences in their theaters, actors, directors and playwrights were left to wait out the pandemic and hope for the safe return of live theater someday.

Several Atlanta theatres are trying or planning new ways to reach audiences. Some are going digital and streaming shows online. Others propose new ways of staging: The Atlanta Opera plans to perform Pagliacci this month in an open-sided tent with masked audience members clustered in small groups; The Alliance Theatre wants to start its 52nd season in November with shows staged in several different ways, including a drive-in version of “A Christmas Carol.” and relatable. But to address gender, race, sexual preference, and economic disparity in American society, she had to learn what it means to be a brave storyteller. Especially after an editor excoriated her debut novel.

We thought this [presumably brief] pause before curtains start to rise again across the metro area would be a good time to meet some of the people who create Atlanta theater.

On the following pages, we present a half-dozen metro Atlantans who have devoted their careers to building theatrical groups and bringing stirring performances to the community. Their paths to Atlanta’s stages have varied widely – from writing plays to acting in plays to building an audience by staging Shakespeare year-round. Let’s hope they will be able to turn on the lights in their theaters soon.

“To tell the truth, fearlessly,” Cleage said. “To not always feel that as an African American writer, I have to write noble women who are always correct, who are long-suffering matriarchs. Those are not the only stories we have to tell.”

The book that the editor criticized was 1997’s “What Looks Like Crazy on an Ordinary Day” –the story of a young Black woman diagnosed with HIV. It went on to be featured in Oprah Winfrey’s Book Club and it became a New York Times bestseller.

Cleage’s play, “Blues for an

Alabama Sky” (1995), was directed by Kenny Leon and starred her Howard University classmate, Phylicia Rashad. The Cosby Show actress gave such a believable performance, an audience member reached out to catch her as she portrayed a staggering, drunken 1930s nightclub singer.

Her play “Flyin’ West” (1992), was featured at The Kennedy Center. It told the story of African American pioneers, starred the late Ruby Dee, and became the most produced new play in the country in 1994. But Cleage calls it all icing on the cake.

“The moment I will always treasure is the first time we had an audience of 200 people at the Alliance Theater,” she said. “And people went crazy. They gave it a standing ovation. They laughed at all of the stuff I hoped they would laugh at.”

Cleage also remembers her critical father praising the performance, and it brought tears to her eyes.

More than 50 years have passed since Cleage made Georgia her home. She still sees America battling some of its same social demons, including in the theater community, where there is still room for diversity.

“There’s a lot of holding these theaters’ feet to the fire and to say, ‘Okay, we love the rhetoric, but what are you going to do about it?’” Cleage said there needs to be voices for women and people of color on every level of a production. “These are great American theaters, and they need to be about the business of telling great American stories.”

Even as the coronavirus has stalled the theater community, Cleage says she’s inspired to write faster. “All of us, by doing the best work we can possibly do, we make those audiences hungry for more good work,” Cleage said. “It’s very important to me that this theatre community thrive. And I’m always grateful to be a part of it.”

Among the shows put on hold by the pandemic is Cleage’s latest work, “Angry, Raucous and Shamelessly Gorgeous” (2019) –a hilarious and poignant story about getting older, as told by an aging actress. And with age, Cleage hasn’t lost any of her spunk either. She’s currently exploring film noir. “It’s been fun for me to see if I can write a bad girl.”

— Tiffany Griffith

Playwright. Essayist. Novelist. Poet. Political Activist. With so many titles next to her name, it’s a wonder that Pearl Cleage can recall specific details about her first night in Atlanta back in 1969. She went to see Black Image Theater put on a play. Cleage remembers the actors wore jeans and black turtlenecks. They talked about the Black community and what needed to be done in the post-Civil Rights Era.

“And I thought to myself, ‘I’m home!’” Cleage said. “’This is exactly the kind of theater I love.’”

The new city welcomed her with open arms. Cleage credits the encouragement, as well as Atlanta’s lively political and artistic scene, for much of her creativity.

“People wanted me to write what I know. And that’s the best gift that a place can give you,” Cleage said. “To make you feel like you’re able to be deeply rooted in that place and reflective of that place. And I hope that’s what I’ve been able to do in Atlanta.”

She would go on to write many plays and books – love letters to the community that fascinates her the most: Black women.

“Because I’m a Black woman. I know myself, so I feel that I know those characters and I want to see women like the women that I know, like the women that I see, on the stage. Because their lives are so interesting,” Cleage said. “I could write those stories forever.”

Though her stories center around women of color, Cleage believes the themes are universal

Special business to open up because of what we do, which is bring people together,” Thomas said.

“All of our training and all of our experience for at least the last 30 to 35 years has been just that — to bring people together for live theater,” Hidalgo said. “Our hands are not only tied behind our backs, our legs are tied together too. We can’t even walk, let alone run.”

It’s a tough spot for these two partners in work and in life who are used to blazing through 20-hour days filled with projects, both at home and at work. Together since they met, and married since 2015, when they were legally able to do so, they live within walking distance from ART Station in a 1940s bungalow they are renovating. These days, much of their time is spent applying for business grants and loans and working toward the day they can finally stage their onhold productions of “Murder for Two” and “Looped.”

From left, ART Station founders Michael Hidalgo and David Thomas

ART Station, a cultural mainstay in the ever-changing landscape of Stone Mountain Village, has been pummeled by the global pandemic. Every employee was furloughed, except for one who takes care of the historic building, which houses a 150-seat theater, a cabaret theater, five art galleries, classrooms, production and administrative space and gift shops.

Co-founders David Thomas, the center’s president and artistic director, and Michael Hidalgo, its producing director and designer, are now “working pretty much as volunteers,” Thomas said.

Two productions of the nonprofit’s professional equity theater company and its summer arts camp were cancelled, along with its biggest fundraiser, the March 17 “Raising of the Green.”

ART Station programs have served more than 50,000 patrons and students in past years. As of now, there’s no telling when the facility will reopen.

“We’re in a really weird place because we’ll be the last kind of

“There’s one word that really summarizes what we’ve been doing. That’s planning. We always plan,” Hidalgo said. “David’s a huge dreamer, and I try to make it realistic. What we do normally is plan, but this is abnormal planning. … It keeps us challenged.”

Thomas and Hidalgo seem to thrive on challenges.

They met in 1983 in graduate school at Virginia Tech and worked together in outdoor theater in Wilmington, N.C., before moving to Atlanta in 1984.

“I was working in insurance to pay the bills while David was living the dream, doing arts stuff,” Hidalgo said.

Thomas was traveling around the state to consult with arts groups as grants director for the Georgia Council for the Arts. He had been thinking of opening an arts center in Midtown Atlanta, but “I came to an arts festival in Stone Mountain … and I saw the Trolley Barn and I just got tingles,” he said.

The Trolley Barn, at 5384 Manor Drive, was built as a trolley station and streetcar barn in 1913, part of a streetcar line from Stone Mountain to Whitehall Street in downtown Atlanta.

Thomas was dazzled by the old brick building, but, “It was in horrible, horrible shape,” he said. “The roof had caved in. You had to wear a mask to go in there. It was full of asbestos.”

And yet, he forged ahead, forming a founding group of artists, government, corporate and community leaders that raised $3.5 million to renovate the building for an arts center. The theater company

Thomas founded in 1986 moved into the building in 1990.

Historic restoration and renovations have continued since, including a project primarily completed in Oct. 2019 that replaced 11 brick archways lost to asbestos removal, renovated the lobby, and installed and added all new seats to the theater.

A Fox Theatre Institute grant funded another major improvement completed after the center shut down in March.

“We now have a brand-new stage with a brand-new turntable inserted in the stage, which is fabulous. Nobody’s seen it yet, but we’re very much looking forward to showing that off,” Hidalgo said.

Donna Williams Lewis

The troupe sought original works. In Horizon’s early days, Adler saw the potential in a story submitted to her on onion skin paper by a local college student. The notes detailed the young Black woman’s experience of being raised by the many women in her life during the 1960s in the segregated South.

“It wasn’t really a play, but I was like. ‘You’ve got something.’ This girl can write,” Adler recalls.

With a little work, that heartwarming story, “Shakin’ the Mess Outta Misery” by Shay Youngblood, premiered on the Horizon stage in 1988, and had two additional runs at the theater. It thrilled and entertained audiences and was performed nationwide. Youngblood continues to have a thriving career. This and people waiting in the rain for Horizon performances, are memories Adler holds close to her heart.

In addition to laugh-out-loud comedies, such as Avenue Q, Horizon also has addressed sober topics, such as the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, sexual abuse, human trafficking, gentrification, and autism. Adler said the variety in their programming reflects Horizon’s mission.

“To connect people, inspire hope, and promote positive change through the stories of our times,” Adler said.

Being a contemporary community theater means reflecting the community the Horizon Theatre is in, Adler said. “It’s a goal of ours to put different races, different ages on stage together,” she said.

Adler has seen Horizon’s audiences grow from being mostly white viewers, to a 60 percent white audience and 40 percent people of color. That number grows to 85 percent when an African American focused show is performed. But Adler said the Black Lives Matter movement is holding them to a higher standard.

being too white, nationally. Locally a lot of anger and frustration coming out over many, many years of what people feel like is racism. Even though there’s a lot of diversity in the work in Atlanta, a lot of the producers are mostly white people.”

Adler said the current power dynamic and culture in theater is under debate about how to make it better. New tools are being utilized, antiracism plans are being created, meetings and trainings are being held. The pandemic has also stalled live theater. “This is the longest time in my entire adult life that I haven’t done a play. And it’s very strange,” Adler said.

The Horizon Theater has weathered the storm with a July furlough, a Paycheck Protection Program Loan, and money in reserves. But she fears layoffs might be unavoidable.

Adler hopes the shutdown will teach people about the value of live theater.

“With the pandemic, people realize what it brings to the community. When you can’t go, suddenly they realize this arts community thing is kind of important,” she said.

In the meantime, the Horizon Theatre is experimenting with new ways to present entertainment– streaming performances and interactive programs. Adler is optimistically commissioning work for a return to safe, in-person acting in January.

“What’s exciting to me is the opportunity to create a world. People walk into an environment, and you create everything that happens to them,” Adler said.

“You’re responsible. You take them on a journey. And the ability to create that world and impact people is addictive.”

Lisa Adler left the vibrant theater scene in Chicago and came to Atlanta. But in the early ‘80s, she noticed something was missing: contemporary theater. She believed Atlanta was missing performances that addressed current issues in modern times with relatable characters.

It was a dream both Adler and her husband, Jeff, were willing to bet on.

“The first play we did we used $1,000 of our wedding money,” she said with a laugh.

With the help of a producer who also wanted to create original work, the seeds for the Horizon Theatre were planted. The show that started it all was “Bonjour, La, Bonjour” by Michel Tremblay

– a French-Canadian play Adler had first seen at the Steppenwolf Theatre in Chicago. “At the time we were growing up, the Steppenwolf Theatre was the hot, young place with all the great young talent that people wanted to be part of,” Adler said.

The couple received heavy praise for their efforts. A second performance soon followed – “Top Girls,” a 1982 play by Caryl Churchill about women in the workplace. “Caryl Churchill was a very cutting edge, popular writer at the time,” Adler noted.

Adler was inspired to run the show because she was determined to showcase plays by and about women.

“Both of those plays had never been done in Atlanta,” Adler said. “And we were looking to bring fresh voices to Atlanta.”

From there, multiple plays snowballed into a season. Atlanta’s theater community showed its support as 300 season tickets were sold that first year. Adler now holds the title of co-founder and Co-Artistic/ Producing Director of Horizon Theatre.

“Black Lives Matter has also hit our community really, really hard. That has been very stressful and emotionally draining for everybody in the community,” she said. “There’s been a lot of accusation of theater

— Tiffany Griffith

Jeff Watkins

Artistic Director, the Shakespeare Tavern Playhouse

Jeff Watkins learned early to play to the crowd.

When he was very young, his father worked as a professional magician and ran a magic shop in Texas. Young Jeff would watch his dad perform close-up magic (the kind with card tricks and disappearing balls) at magicians’ conventions and other gatherings.

After college, Jeff took up street magic for a while himself. With a freshly minted college degree, including a minor in theater, he moved from Texas to New York to make his fortune in show business. He auditioned for acting jobs and paid for groceries by doing sidewalk shows.

“Washington Square was the most fun,” he said. “Wall Street is where I made the most money.”

Like most starting actors, he spent much of his time just looking for work. He landed a job with a six-actor company that toured the northeast in a van and a car and staged shows in schools and community centers about various literary figures. In the early 1980s, he headed west to Chicago to join some college friends who were organizing a theater group there.

A couple of years later, as Watkins was driving from Texas to New York for yet another audition, he stopped off to visit a friend in Atlanta. She ran a group that staged readings of Shakespeare’s plays in local bars. When his friend decided to move

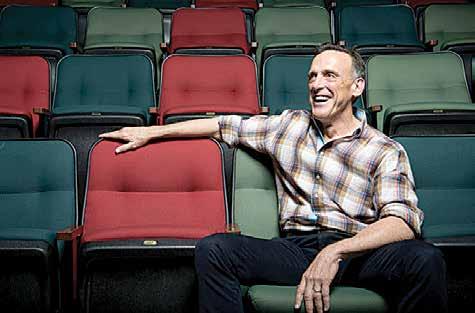

Tom Key Actor, playwright, director

to New York herself and leave the Atlanta Shakespeare Association behind, “I said can I have it?”

Watkins said.

Watkins became the group’s artistic director. In 1984, the group staged a production of “As You Like It” in a back room at Manuel’s Tavern, a storied Atlanta watering hole where politicians, cops and journalists gathered. One early show, Watkins said, was a political fundraiser.

Playing Shakespeare in a barroom turned out to be a dissuaded from that.”

He calls his style of presentation “Original Practice,” meaning he stages plays as he believes they originally would have been performed. Productions follow the text, employ no dramatic modern sets or updated sound effects, and use only fabrics and clothing from the period. His actors don’t pretend there’s not an audience sitting just a few feet away. “At Manuel’s, I said this is the vibe I’m after,” he said.

Here’s Where to Find Theaters

230 productions of Shakespeare’s plays, he said, and twice preformed the full “canon” -- 39 plays attributed fully or in some form to Shakespeare.

“I’ve done more Shakespeare than anybody else on the North American continent,” he said one recent afternoon as he sat on the porch of his Decatur home, “and maybe more than just five or six people in the U.K.”

In 1990, the company moved into the Shakespeare Tavern Playhouse at 499 Peachtree St. in Midtown Atlanta. The 200-seat Tavern staged more than a dozen plays a year until the COVID-19 pandemic forced it to close in March.

Watkins doesn’t know when his troupe will return to live performances – mid-next year, he guesses – but he has plans to expand so he can someday do even more of the kind of plays his fans have nicknamed “Shakespeare for NASCAR fans.”

For current information on when individual metro theaters plan to reopen their main stages and on whether and how they are presenting theatrical events now, check their individual websites.

7 Stages Theatre: 7stages.org

Act3 Playhouse: act3productions.org

Actor’s Express Theatre Co.: actors-express.com

Agatha’s A Taste of Mystery: agathas.com

The Alliance Theatre: alliancetheatre.org

ART Station: artstation.org

Atlanta Lyric Theatre: atlantalyrictheatre.com

Atlanta Opera: atlantaopera.org

Aurora Theatre: auroratheatre.com

City Springs Theatre Co.: cityspringstheatre.com

Dad’s Garage Theatre: dadsgarage.com

Dinner Detective Murder Mystery Dinner Show: thedinnerdetective. com/atlanta

Earl and Rachel Smith Strand Theatre: earlsmithstrand.org

Found Stages: foundstages.org

Georgia Ensemble Theatre: get.org

Horizon Theatre Co.: horizontheatre.com

Kenny Leon’s True Colors Theatre Co.: truecolorstheatre.org

Legacy Theatre: thelegacytheatre.org

OnStage Atlanta: onstageatlanta.com

Out of Box Theatre: outofboxtheatre.com

Out Front Theatre Co.: outfronttheatre.com

Pinch ‘N’ Ouch Theatre: www.facebook.com/pnotheatre

Shakespeare Tavern Playhouse: shakespearetavern.com

Synchronicity Theatre: synchrotheatre.com

Stage Door Players: stagedoorplayers.org

Theatrical Outfit: theatricaloutfit.org

Village Theatre: villagecomedy.com revelation. Watkins saw what he thought his productions should be – directed to the audience and, for lack of a better word, entertaining. “I had been a street performer,” the 64-year-old said.

“I know in my stomach – I know in my gut – when it’s working with an audience. I cannot be

At first, his plays weren’t always popular with critics who thought Shakespeare should be treated seriously and updated to reflect modern times, he said. But his shows found an audience. Watkins’ company has staged Shakespeare for more than 35 years. It has presented more than

And he’s convinced that sitting back with a draft Guinness and watching a sword fight from your bar table as you dine on shepherd’s pie is the best way to see Shakespeare. “What I’ve created connects to the audience,” he said. “If you think Shakespeare isn’t your playwright, you need to spend more time at the Shakespeare Tavern … and this beer will help.”

— Joe Earle

Because having the confidence and peace of mind of accreditation is important. That’s why The Piedmont is accredited by CARF International, an independent organization that sets exceedingly high standards for care and service. It’s a lot like an accreditation for a hospital or college. Or a five-star rating for a hotel.

So if you’re looking for assisted living services, take a good look at The Piedmont at Buckhead. We think you’ll find that our CARF accreditation is only one of the many reasons you’ll like what you see.

Atlanta actor Tom Key has never been one to shy from a difficult topic, conversation, decision or role.

At 70, he’s still at it. After retiring in June as artistic director of the Theatrical Outfit in Atlanta, Key is auditioning for film and TV work, has gotten involved in social causes and is hopeful he’ll be back on stage in Atlanta again by the spring of 2021.

The author of the “Cotton Patch Gospel,” a show that reimagines the story of Jesus set in the rural South of the mid-20th Century, also is contemplating writing another play. “I am working to develop a writing habit,” he said. “I’m about two months into it. I want to get to the point where I’m writing every day, because the times are so challenging.” continued on page 10 continued from page 8

He wants his new project “to show that what unites us is greater than what divides us, and that we all belong to each other.”

Key grew up in Birmingham. In 1963, when he was only about 13, the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in his hometown and the deaths of four young girls in the bombing showed him powerful, horrifying lessons about race and the need for community. “My whole view of reality was changed,” he said. “It was a formative experience.”

Fast forward to 1968. Key made friends with a roommate who was a young man of color and made plans to bring him home at Thanksgiving. No, said his shocked parents. If you do that, we’ll stop paying for your tuition and your car.

“So, I took them up on it,” he said simply. “We maintained a civil relationship, but there was a real gap or wound that was just there.”

After moving to Knoxville, he emerged from the University of Tennessee in the late 1970s with an undergraduate degree in English literature and a graduate degree in theater.

“Cotton Patch” followed. It started as a one-man show and flowered into an off-Broadway musical. Key toured with it, eventually landing in Dallas for a two-year stint with a theater company there.

In 1986, Key and his family moved back to Atlanta. About a year later, he was offered a job as artistic director an off-Broadway theater in New York. He decided to stick with Atlanta, his “home place in the South,” he said, because he felt it offered a better environment for broadening his directing and writing skills and perhaps starting a small theater company. “New York theater is like the state fair where the tomatoes are judged,” he said. “But the tomatoes are not grown in the soil of the midway.”

He carved out his reputation through extensive work at the Alliance Theatre and through touring “Cotton Patch” and “C.S. Lewis on Stage,” a one-man show based on the British writer. Film and TV opportunities came along.

An artistic director’s job came calling again in 1995, this time with the Theatrical Outfit. It encompassed a grab bag of duties from picking out, casting and occasionally acting in and directing plays to forming and encouraging creative teams. Key also functioned as a public advocate and money-raiser for the theater.

The theater’s plays ran the gamut, but more than a few tackled thorny questions related to race, sexual orientation or faith. “I always ask the question, ‘What do we need to have a conversation about right now?’ And sometimes the answer was, ‘We really need is to have a good time right now.’”

The longtime Atlanta theater veteran recounted how presenting envelopepushing productions sometimes occasioned pushback.

In some places where ‘Cotton Patch” was being staged, fundamentalists took out ads in local newspapers calling it “blasphemous” and urging people to stay home.

And Key remembered how a 1982 run of the play at the Alliance Theater featured a live discussion following each performance.

One night got especially ticklish. “A woman in the front row asked, without any hesitation or apology, why I made the [Ku Klux] Klan a bad force in the story because [she said] it was an organization founded to protect Christian women and children,” he recalled. Key said he paused for what seemed a long time, then -- “in the same way that bombs are defused-slowly and carefully.”

-- he explained why he had the KKK play a role in the lynching of Jesus in his play.

The longtime Atlanta actor said over the years he was asked to join productions that espoused a stance or an opinion and sought to demonize those who deviated from it. He always politely refused, he said.

“I turned down a play about the Holocaust because with it came a vision that we are animals just surviving and humanity has no moral basis. It wasn’t just that I disagreed with the idea, I literally would not know how to play that role.”

Now he returns to writing. “I plan to write about the human condition,” he said. “I believe fundamentally in the core of my being that we are part of a story that’s going to end well, even when we’re in the worst of times.”

— Mark Woolsey