3 minute read

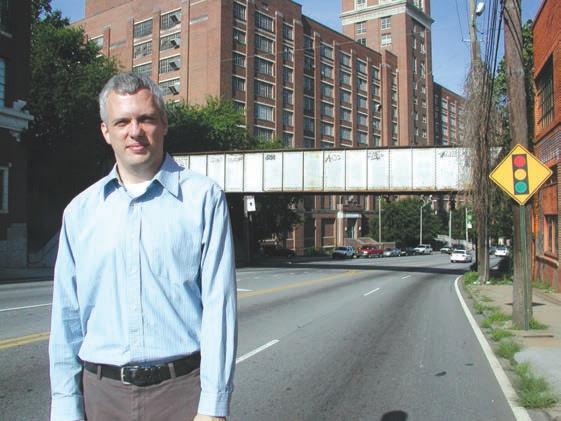

Ryan Gravel and the Atlanta BeltLine From idea to advocacy to transformation

By Clare S. Richie

Most of us know the Atlanta BeltLine. It’s where we walk, bike, run a 5K, watch the lantern parade, access parks and other neighborhoods. We’re hungry for this type of sustainable connectivity and community, which started 15 years ago as an idea from then Georgia Tech graduate student, Ryan Gravel.

A er spending his senior year in Paris, where he walked everywhere, ate fresh foods, and lost 15 pounds, Gravel thought deeply about the role of city infrastructure in how we live our lives. Sidewalks versus highways, for example, encourage di erent lifestyles.

“Atlanta is a railroad town,” Gravel explained, “with compact, mixed-use intown neighborhoods built around streetcars.” Gravel was fascinated by trains as a child growing up in Chamblee. So, when he needed a cityscale design project for his master’s thesis, Gravel knew what infrastructure was missing to revitalize Atlanta –transit. His master’s thesis became the kernel of a vision that would transform a 22-mile loop of old railroads with transit, trails and green space to promote economic growth and quality of life in 45 neighborhoods.

Needless to say, Gravel graduated, and his idea was temporarily shelved as he went to work for an architecture rm. It was his master plan for Inman Park Village, deciding whether or not to place the parking

Downtown, where all the lights are bright...

deck close to the old railroad line, which compelled Gravel to share his idea with his colleagues. at was the spark. In their free time, Gravel and his colleagues mailed out letters and maps detailing the vision. Cathy Woolard, Atlanta City Councilmember at that time, was frustrated by the lack of city transit and embraced the Atlanta BeltLine. “With Cathy’s help, we used the NPU [neighborhood planning unit] system as a framework for sharing the idea all around the city,” Gravel recalled. From 2001 through 2004, Gravel spent countless evenings and weekends talking to NPUs, neighborhood groups, schools, churches, businesses, and anyone else who would listen. e idea grew into a grassroots campaign of local citizens and civic leaders, with Gravel working full time for Friends of the Belt Line. Other groups added to his idea. e Trust for Public Land proposed 1,400 acres of new parks, Trees Atlanta asked to plant an arboretum, Mayor Shirley Franklin suggested an a ordable housing initiative, and more. Gravel welcomed these new ideas – they were better for the city and built a broader constituency.

Yes, we actually published a separate edition called Atlanta Downtown for a short time. e lead story from November 1997: the planned demolition of the Omni Coliseum to make way for Philips Arena. ere was also a feature on how chess had become popular in Woodru Park, with players gathering daily in good weather for friendly matches.

In 2005, the 6,500acre Atlanta BeltLine Tax Allocation District (TAD) passed with broad-based support and is expected to generate approximately $1.4 billion, covering close to one third of the total program cost. e same year, Friends of the Belt Line merged with Mayor Franklin’s Atlanta BeltLine Partnership. Wearing many hats along the way – Friends of BeltLine sta , city planner, Atlanta BeltLine Partnership Board member, and currently an urban designer at Perkins+Will – Gravel remains dedicated to the BeltLine and proud of all who came together to make it happen. e BeltLine is a model and the world is watching. In fact, Gravel’s passion for revitalizing infrastructure has him traveling the world to research, document and tell the story of how cities like Los Angeles, Toronto, Detroit and Rotterdam can transform degraded rivers, canals, and railroads to renew their cities, health and spirit.

“ e BeltLine is already doing what we said it would do,” Gravel said. e rst two-mile phase of the trail is a popular city feature with a 3:1 economic impact, turning a $350 million investment into more than $1 billion of new mixed-use redevelopment. His favorite picture is a woman walking on the BeltLine with her groceries. “It is already showing us how Atlanta can revitalize its infrastructure to promote a more sustainable life.” ere’s still work to be done. e Eastside Trail design calls for access points to Ponce de Leon, lighting, and water fountains accessing water lines crisscrossing under the trail. “We could see trains in the corridor in the next ve years if we push for it. Let’s pass a referendum and collect the funds we need to get it done,” Gravel urged.

“ e BeltLine will evolve over our lifetime,” he re ected. For Gravel, future phases should include a more robust public art program with permanent exhibits, performance venues, and artist housing and work spaces. It should also include equitable access for all income levels, green standards for building in the corridor, and community food networks.

By Collin Kelley INtown Editor

Once the Battle of Atlanta painting leaves Grant Park for its new home at the Atlanta History Center, the historic Cyclorama building will undergo a massive interior transformation.

Atlanta-based sustainable design rm Epsten Group has been tapped by Zoo Atlanta to transform the circa-1921 building into a new event space and restaurant with a viewing area overlooking the African elephants, zebras, and gira es in their savanna habitat.

Peter Choquette, design and consulting department manager at Epsten Group, said it’s too early to announce a budget for the renovation project, but the wish list for the Cyclorama building is being eshed out.

e completion date is set for 2018, which gives the Atlanta History Center time to construct and build a new home