5 minute read

Above the Waterline

Devastating hurricane strikes beloved island

ABOVE THE WATER LINE

Sally Bethea Sally Bethea is the retired executive director of Chattahoochee Riverkeeper and an environmental and sustainability advocate.

On an overcast morning in mid-October, my journalist son Charles Bethea boarded a small boat to reach the shores of Sanibel Island—three miles across the choppy waters of San Carlos Bay on Florida’s Gulf Coast. The causeway to the island was in pieces, damaged by 150-mile-per-hour winds and extreme storm surges that washed away portions of two man-made islands connecting spans of the bridge. In my heart and mind, I was with him, waiting anxiously to learn the extent of the damage from Hurricane Ian: the nightmare storm called historic for its intensity. The maelstrom bashed the southwest coast of Florida on Sept. 28—the day my mother would have turned 102. My sister and I were relieved that neither she nor our father lived to see the catastrophic destruction of the place they—and we—so love.

A disaster waiting to happen

Sanibel memories

In the late 1950s, when my family first vacationed on Sanibel, it was largely undeveloped. We loved the island's natural beauty despite the relentless no-see-ums and rustic accommodations. We collected shells on its beaches, visited the national wildlife refuge that comprises a third of the island, boated with friends, fished for snook, and painted watercolors of coconut palms waving in the ocean breezes.

In the backwaters of mangrove swamps, we waded barefoot—at times in waist-deep water— cautiously exploring the muddy bottom with our toes, seeking king's crown conches. We watched the ever-changing shoreline, altered through the seasons and years by wind, waves, and currents. My parents loved Sanibel’s wild nature—its red mangrove forests, flocks of roseate spoonbills, and rare junonia shells—and did what they could to help preserve it.

Until 1963, when the original Sanibel Causeway was completed, we took a ferry, then in operation for more than fifty years, to reach the island. We would race in our hot, unairconditioned car to make the last departure of the day after the long drive from Atlanta, my father ever certain we wouldn’t make it in time. We always did. Fifteen years ago, a new causeway replaced and upgraded the original, but it was no match for Ian’s destructive force. My father worried every year that a deadly hurricane might hit Sanibel and harm the island and the house he and my mother built there in the early 1970s. He was well aware they had chosen a site on the beautiful but shifting sands of a barrier island, vulnerable to storms and the sea. He also knew that nearby Fort Myers on the mainland had once been a maze of swamps and mangroves, prone to frequent flooding. It was all a disaster waiting to happen.

Yet, as the years passed, people continued to move into the region: one of the fastest-growing areas in the country. New houses were built and mobile homes were placed mere feet from the water, often on “land” created by developers who used dredge-and-fill methods. River bottoms, marshes, and lowlands were scoured for fill material to elevate building sites surrounded by artificial canals to manage drainage and create “waterfront” property.

Sanibel employed a different approach for its inevitable growth, one that in all likelihood saved lives and property from the wrath of Ian. Beginning in the 1970s, local officials and residents (about 7,000 people live on the island yearround) decided to work with nature to protect the island’s environment and curtail overdevelopment. Ordinances limited development and officials rejected engineered structures, such as sea walls; instead, living shorelines were installed with natural materials, and environmentally sensitive areas were preserved. Today, twothirds of the island is designated as conservation land.

Prior to its incorporation in 1974, when Sanibel secured autonomy to make land use decisions, county officials projected that 30,000 residential units could be built on the island: a sandy strip of land twelve miles long and three miles across at its widest with an average elevation of about four feet. Although it’s difficult to acknowledge at the moment, Ian’s devastation could have been much worse.

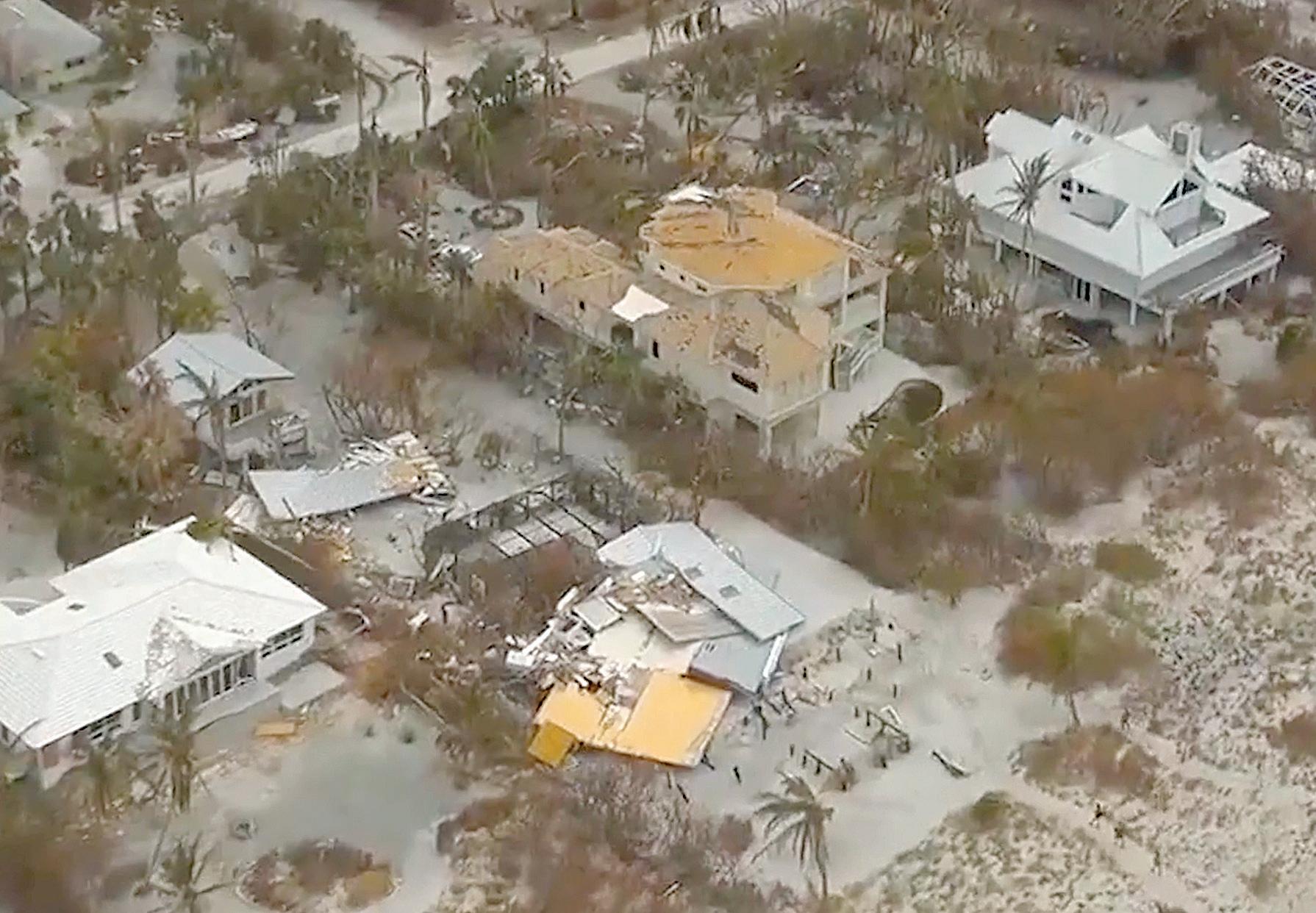

Destruction on Sanibel Island, Florida. (Courtesy CNN) Climate change

More than 90 percent of the excess heat from global warming over the past fifty years has been absorbed by oceans, which is where storms gain strength. Higher surface water temperatures allow hurricanes to reach high sustained wind levels. Warmer oceans also make the rate of intensification more rapid. Globally, oceans have warmed an average of 1.5 degrees Fahrenheit in the past century and their surface temperatures continue to rise.

Climate scientists say there haven’t been more hurricanes in recent years, but that, since 1980, storm intensity has increased. More storms have been major hurricanes (Category 3 or above) with an increase in those that undergo rapid intensification; they are also producing more rainfall than in the past—another result of climate change.

I finally heard from Charles the morning after his long day of reporting on Sanibel. Apocalyptic was the single word he chose to describe the wreckage. When Gulf waters submerged the island, the ground level of every building was ruined; where walls were still standing, interiors were filled with mud and mold. Smells were nauseating from broken sewage lines, dead animals, oily substances, and general decay.

Unable to reach my parents’ former house, which they sold in the 1990s, Charles serendipitously met a neighbor who showed him a post-hurricane photo. The sturdy concrete walls and roof appeared intact; however, the interior was a dirty wasteland like every other building in the neighborhood. The house my parents loved may have to be demolished.

Charles spoke to many people, all of whom said they hoped to rebuild, once insurance checks arrived. Will they erect the same expensive homes? Will the city of Sanibel adopt building codes requiring more storm-resilient structures? Will new land conservation and restoration projects be prioritized? Perhaps the most important question of all: Does it make any sense to rebuild on a barrier island in the age of climate change?