13 minute read

THE GREAT DIRTBAG CHALLE NGE You’ve for $1000 and 30 days, now go build a bike, no Harleys allowed

THE GREAT DIRTBAG CHALLENGE

You’ve got $1000 and 30 days, now go build a bike, no Harleys allowed…

Advertisement

You and your buddies, hanging out in your garage, have probably come up with some pretty good By Gabe Ets-Hokin Mission District. As the 16 finishers (of 28 entries) rolled in after the 100-mile pre-judging ride, hyper-amplified bands played death ideas, but have you had any that turned metal, beer-slingers poured cheap brew and into a 10-year tradition, an iconic event spectators gawked at scantily clad “alternathat’s imprinted on your local motorcycling tive model” Ashley Russel, wrapped in just scene? enough fishnet with, fittingly, electrical tape

Poll Brown has. Ten years ago, the imppasties to keep the event barely this side on ish Englishman and three of his buddies an NC17 rating. were “standing around, bullshitting” about In fact, there were far too many people the then-current crop of biker build-off prothere to get good photos of the bikes and as grams on cable TV, shows where the average Mr. Editor Edwards abhors the usual “asses & chrome-encrusted V-twin started around elbows” shots taken at these things anyway, I $50,000. They challenged each other to a arranged a photo session several weeks later budget bike-building duel, and at first, there were only so I could have some quiet and order while photogratwo rules: 1) You can’t spend more than $500; and 2) you pher Bob shot and I interviewed participants. But that get just two weeks to finish it. The deadline came around, backfired. Put Dirtbags in an open space and as soon as and about 30 of their friends showed up to celebrate the they get bored they start doing burnouts and stunts with results. The party was somehow too raucous for Oakland their machines, making interviewing difficult but pho(“The OPD was not user-friendly,” says Brown), so the tography fun. next year the event moved to San Francisco. Talking to the Dirtbags who showed up made it

It was now a thing, and as most things do, it took on a clear that their bikes have taken on a certain distinclife of its own. Year two there were six entries, and more tive look over the years. Generally, they tend to be ‘70s each following year. Rules evolved – Brown’s original and ‘80s Japanese UJMs, with modified hardtail frames partners quit the event, and as he believes motorcycles and creative use of cast-off parts like gas tanks, seats are meant for riding, not posing, he added the requireand wheels. The $1000 doesn’t include old abandoned ment that the bikes get ridden on a 100-mile loop before projects or parts the participants (or their friends) may judging. Entrants complained about the $500 rule, so already have had in their garages and sheds, nor does that was bumped up to an extravagant $1000. Two the 30-day rule apply to stuff they may have already weeks turned into 30 days, and the final rule – no Harstarted but failed to finish. Adherence to the rules is on ley-Davidsons – was added. Brown says Harleys, with the honor system. their distinctive shapes and glittering chrome, gobble up The event is well attended and sells a lot of beer, burgattention at shows, so he decided to “level the playing ers and T-shirts, but still barely breaks even, according to field” by excluding the brand. Brown. But he won’t quit. “Every year I question doing

Brown has used social media to massively grow the it,” he says, but he continues because it makes his friends event. Now called – and himself – so the Dirtbag Chalhappy. “Some of my lenge, attendance best friends I met has increased at through the DBC and least tenfold. The the response I get from 2012 iteration, held the community is enorin a grubby space mous,” Brown tells me between warehouses in his working-class in the Hunter’s Point British accent. “People neighborhood of San I don’t know stop me Francisco, attracted on the street and tell hundreds and hunme what a great time dreds of motorcythey had. They say clists, artists and it’s like Christmas for even curious hipsters grown-ups. It makes from the nearby me feel good.”

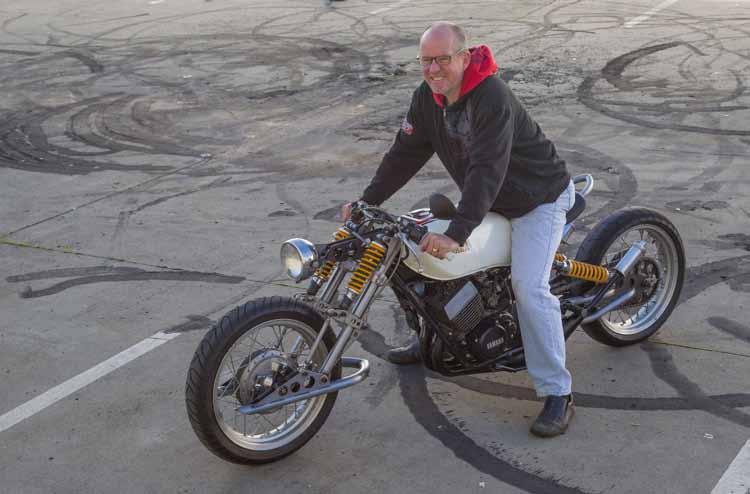

Julian Farnum: Yamaha RD400 Streetfighter

Livermore, California’s Julian Farnum is a product designer by trade, and has always been obsessed with building roadrace frames and alternative front ends – plus he loves two-strokes, especially RD and RZ Yamahas. This low-riding RD400 is his first Dirtbag entry, and it’s amazing he accomplished it for under $1000, especially when you see the “Öhlins” stamps on the four shock absorbers. Actually, they’re just Öhlins springs with cheaper Mulholland dampers. A $75 RD frame was the basis of the project, a friend had a ‘79 RD400 Daytona Special gas tank, another friend donated R5 wheels, hubs and brakes, and the motor’s bottom end and crank turned up on a twostroke Internet forum. Exhaust comes from an RZ350 and the seat is off a Suzuki GSX-R600. Luckily 1 3 /4-inch steel tubing fit perfectly in the GSX-R600 triple-clamps, and Farnum developed the leading-link springer front end himself, noting without really needing to, “I added my own design twists.”

Julian’s process was definitely more involved than the Sawzalland-blowtorch method most Dirtbaggers employ. “I spend two hours a day commuting on the train, so I did 50 pages of sketches, which turned into CAD models, then individual part drawings and then finished pieces. So when the Dirtbag go-date hit, there was no guesswork involved, all I had to do was go into my shop and start,” he says.

Guido Brenner: Guzzi-Ford Trike G uido Brenner is the prototypical San Francisco Renaissance Man – nightclub bouncer by night, quasiindustrial tinkerer and builder of cars and motorcycles by day. He’s also a photographer and in four bands, so it’s not surprising 2012 was the first year he was able to find the time to participate in the DBC. “I’m the one usually doing a sideshow with a sidecar (Brenner is known for doing burnouts and flying the chair of his battered BMW sidecar rig during the DBC after-party), but this time I decided to get off my ass and build something.”

Brenner was born into a family of hotrodders, so it’s not surprising he selected the ancient front end of a 1930 Ford Model A to mate to the frame, rear wheel and motor of the small-block Guzzi he rode around in the ‘80s. “I bought the bike back from a friend for $500,” he says. Being a hot-rod guy, he wanted to sit behind a steering wheel, in front of the Guzzi V-twin. “It’s the po’boy version of a Morgan trike,” he laughs.

It’s also very much a work-in-progress. The 80-year-old mechanical brakes, not surprisingly, are marginal, making the pre-judging ride “hairy.” Brown and other riders were nervous riding behind Brenner, but a team of Christian Motorcycle Rider volunteers provided escort, keeping other motorists off his tail. At the end of the day, Guido’s creation went home with the Founder’s Award and he had a great time – he loves the comfy car seat and next year he wants to build a half VW Beetle/half chopper monstrosity. I won’t want to ride that one, either.

Jason Pate, who does underground construction and welding for a living, has his shop in industrial, blue-collar Fremont, so his 2008 entry, a 1979 Suzuki GS1000, reflects the tough-but-stylish East Bay zeitgeist. The build ran him just $850, with money saved by using a ‘79 GS750 front end, chopping and welding the hardtail conversion himself and making his own rear brake pedal. Points were replaced with the mechanism from a Chevy V-8 – Pate is proud of the built-in timing light.

The bike was finished off with the tank from a ‘75 Triumph, while the hubs and wheels were donated by Crazy Chris at Wheelworks, the Bay Area’s go-to shop for wheel lacing. The bike’s tidy, compact and clean look was a crowd-pleaser, garnering the “Clever Fucka” and Coolest Chopper trophies.

Pate insisted I ride the bike to get a feel for it. I was game – never having ridden a hardtail before. I thought the horrible ghetto pavement around Hunter’s Point would destroy what’s left of my lower spine, but it was actually not that bad, the big back tire and mountain-bike shock mounted under the saddle absorbing a lot of bumps. The best part about the bike was that smooth-running and torquey GS1000 four,

which ran perfectly and sounded great. There’s a reason four-cylinder Suzukis are fast-becoming Dirtbag favorites.

Since the 2008 event, Pate has kept the bike as his regular ride, repainting and polishing it to its present glory. Stuff occasionally rattles loose on the freeway, but he still enjoys it: “It’s capable and fun...I like the ‘60s chopper thing, the classic bare-bones look.” For $850, I’d call it a keeper.

Jason PatE: 1979 Suzuki GS1000

The Turk: Yamaha “Bulldozer” and Yamaha “Slung-Low”

What’s your name?” I asked the builder of the two most unusual bikes in the group.

“Turk,” came the reply from behind his big sunglasses.

“No, what’s on your birth certificate?”

“I don’t remember,” was the vaguely coquettish response.

“How about your driver’s license?”

When he replied, “The Turk,” I stopped asking questions about his name.

The Turk is another product of San Francisco’s industrial-artistic lifestyle, the subculture that produced the Survival Research Labs’ self-immolating robots and Burning Man. His day job is with the San Francisco Opera and Ballet, building props and sets – he recently built a radio-controlled chaise lounge for the annual Christmas production of The Nutcracker.

The “Bulldozer” is what happened when Turk “wanted fat and heavy, with big wheels” for his 2011 DBC entry. The huge main frame tube was one of the easiest parts to source – an industrial specialty shop rolled the tubing and bent it to order for $160. Turk then welded on the rigid swingarm and girder front end. He copied the latter’s design from the front-end geometry of his neighbor’s land-speed racebike. The chromed tractor seat is off an Excercycle from the ‘30s, and the bike rolls on a pair of fat Suzuki Bandit rear wheels. The Yamaha Radian motor isn’t all that interesting, but it makes enough power for freeway speeds and smoking the rear tire at the end of the day. Big, hulking and, incredibly, built in just 30 days, the Bulldozer won the People’s Choice award last year.

In 2009, Turk was in a lower and slower mood. “Slung Low” was the result of having a good Yamaha XT550 dual-sport motor in a badly twisted frame cluttering his shop. “I wanted to

make a frame any shape I wanted to,” Turk told me, so he started out with $60 worth of pipe and used hand tools and a hand-held grinder, “nothing fancy,” to make an elegant chassis that follows the curves and angles of the old Thumper’s mechanical parts. Some anonymous ‘80s Kawasaki cruiser donated its front end and back wheel, and the gas tank appears to be a pony keg. The seat looks more like a photograph of a seat, and ergonomics are more akin to the Big Wheel I owned when I was 6. A beautiful piece of artwork, but the first motorcycle I’ve ever encountered that I have absolutely no desire to ride.

Felicia Chen: Kawasaki Ninja 250 Chopper

San Jose State neuroscience student Felicia Chen is unusual for a Dirtbag entrant, an outsider, a woman of Asian descent and gay to boot. But that didn’t stop her from entering the contest, building her bike, completing the ride and impressing the heck out of the Supreme Dirtbag himself. “She should have won everything,” Brown told me. “That was the first bike she built, she never had a problem and it was impeccable.”

Chen’s project shows her scientific approach to things. She started with the remnants of a friend’s 2005 Kawasaki Ninja 250R (“She lunched the engine.”) and found a cheap replacement motor for it. From there, she got together with friends in her riding club, The Creeps of San Jose, and brainstormed: “It’s like 2 in the morning and you say stuff like, ‘Wouldn’t it be cool if...’” Chen says she didn’t “know a lot about choppers, but I

wanted a little seat with the springy thing,” as well as the hand-shifter with clutch lever attached. The result is small, neat, clean and precise – as you’d imagine a chopper built by NASA might look. DJ Cycles in San Jose, an independent shop, let Chen use a lift and tools and helped with welding, though Chen was definitely handson: “They didn’t just do stuff for me, they taught me how to do stuff...I cut up my hands pretty bad, metal splinters and stuff, but I guess it’s not a Dirtbag unless you bleed on it.” Chen relishes her newfound Dirtbag status. “I didn’t know how they’d receive this small Asian chick, because I’m not that dirty, but I got a lot of props from the guys,” she says. What’s next? “A Yamaha XS400 café-racer – after I let my girlfriend wreck it…”

THE GREAT DIRTBAG CHALLENGE "Brown used social media to massively grow the Dirtbag Challenge; in a decade attendance has increased at least tenfold." Alex VerbitskY: Honda CB450 Board-Tracker

Twenty-nine-year-old self-described “IT guy” Alex Verbitsky came to California by way of Virginia from Moldova, of all places, five years ago. The ethnic Russian “grew up on American style” and always had some kind of retro-styled motorcycle.

Verbitsky’s DBC ride reflects a bare-bones ethos. “El Fo-Fitty” started life as a 1968 Honda CB450, and aided by his new Dirtbag friends, Alex welded up a hardtail frame and mated a 1963 Honda Dream front end. Wheels are ex-motocrosser, a 23-inch front and 21-inch rear. The gas tank is a fiberglass Bultaco trials unit, carefully painted by artist Talbott Deville to look old and patina’d. Verbitsky was going for a “rideable board-track

style,” but his scrounger nature, perhaps born of necessity in post-Iron Curtain Moldova (Europe’s poorest country) shines through. The bandana-patched seat is off a bicycle (perhaps my older brother’s Schwinn Stingray, stolen in San Francisco in 1975), the exhaust is an old ‘70s-era Hooker 2-into-1, handlebar risers are suspension links from a Suzuki, the bars themselves are made from a truck-engine camshaft, and the wicker front fender (maybe the first ever) was some kind of barstool or nightstand, Verbitsky isn’t sure which, “but it was $5.”

His bike has yet to complete the ride, but failed entries can be re-entered the following year, so long as work doesn’t start until 30 days before the event. Alex’s ride isn’t fancy, but it’s a good example of what can be done in a month with the right parts, friends and vision – it’s what the Dirtbag Challenge is all about.