12 minute read

Rhythms Sampler #13. Our Download Card

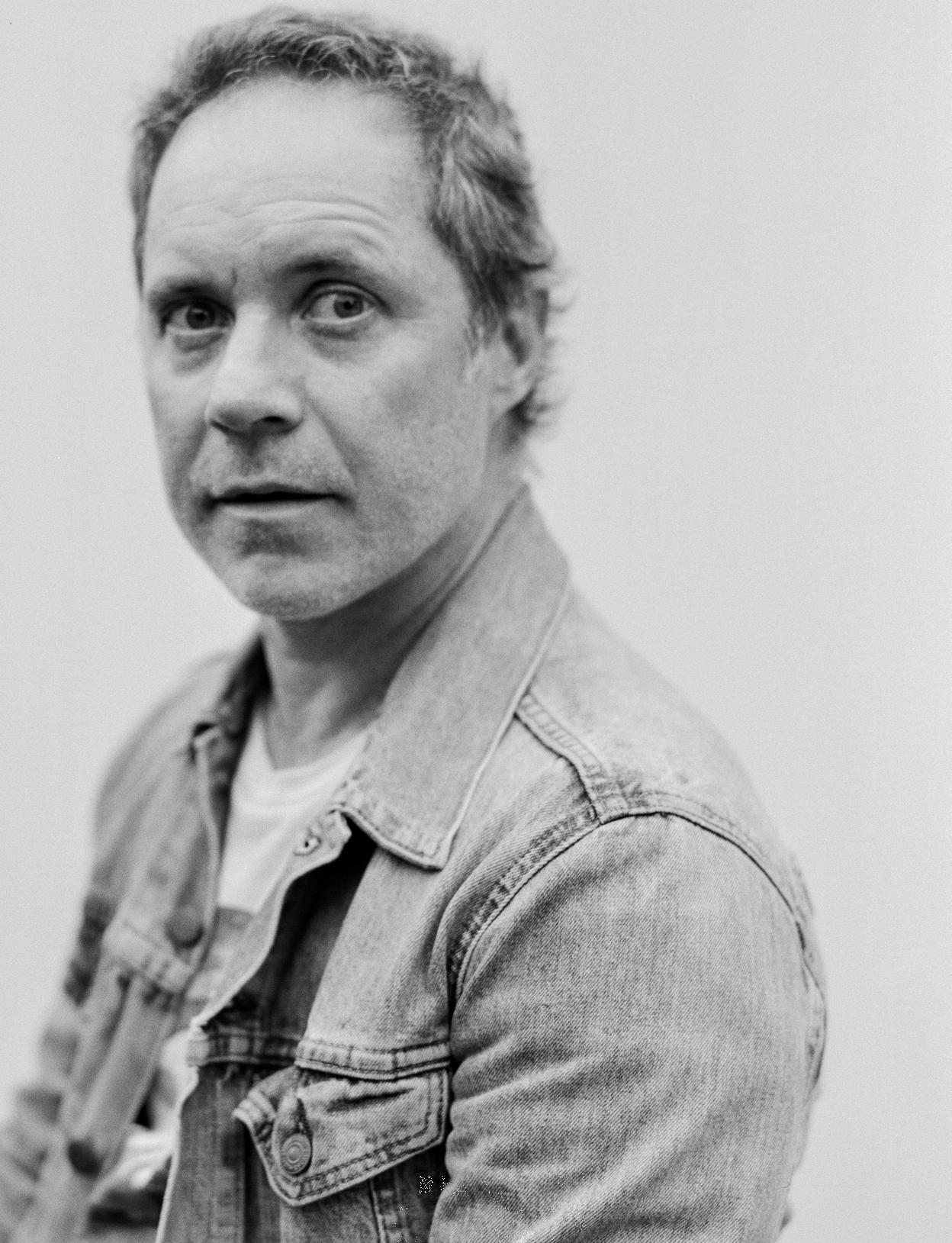

DEFYING THE ODDS

Despite a career spanning over two decades, it’s only now that Jeb Cardwell is releasing his solo debut, writes Samuel J. Fell

Advertisement

Chances are you’ve heard Jeb Cardwell play. His guitar and banjo work, admired and respected by all who come across him, have graced stages and albums for the past twenty or so years, as he’s played with Kasey Chambers, Shane Nicholson, sister Abby Cardwell and countless others. He’s an Australian roots music journeyman, and he has his craft down pat. And yet, during all this time, Jeb Cardwell has never released an album under his own name – until now. My Friend Defiance stands as his solo debut, an album that carries with it the poise and assuredness that comes from two decades of playing, writing and singing with the best of them. And it’s not, as one could easily assume, the result of a long Covid lockdown. Cardwell was ready to go with this one before the world stopped in March last year, writing in the album’s liner notes, “I intended to release this record at the beginning of 2020 but then the world pandemic occurred so, I decided to wait until 2021.” “Yeah, that’s right, not one of these songs was written during Covid, not one of them was written during the [pandemic],” he confirms. “During the past year [though], I decided to do a bit more postproduction, which I feel brought the songs to their full maturity, which is a bit of a silver lining there.” The songs are indeed mature. My Friend Defiance is a study in thoughtful songwriting, nothing is overstretched or overplayed, and to be quite honest, you’d expect nothing less from a player of the calibre of Cardwell, despite the fact he’s not entered this realm before. I venture then, that coming out of the shadow of, say, Kasey Chambers (with whom he played on the 2012 album, Wreck & Ruin) and into the spotlight would have been somewhat of a nerve-wracking experience. “Yeah, playing with Kasey or Shane Nicholson or my sister, you’re in the studio and you’re conscious of doing your best, and you’re proud and excited to be there, but it’s not your baby though,” he says. “You do become invested in it, you care a lot about it, but you didn’t write the songs. So with me putting myself out there, for me it’s weird because I’m not… me in the spotlight, it’s funny.” “People say, you’re in the wrong industry if you don’t want to be in the spotlight,” he goes on with a laugh, “but I’m uncomfortable with a lot of attention. So putting myself forward like this is pretty strange.” In order to combat this feeling of being out of place, so to speak, Cardwell surrounded himself with a slew of crack players in order to bring these songs to life – bassist Tim McCormack, drummer Roger Bergodaz and keysman Brendan McMahon make up the core band, with additions from Michael Hubbard, Lachlan Mclean and Butch Norton, plus an array of backing vocalists including Chambers, Abby Cardwell, Talei and Eliza Wolfgramm and Zane Lindt. All contribute to the record’s strength and power. “When I was recording the album, I thought, I’ve got these songs, I feel they’re good songs, and they deserve to be recorded,” he says, when I ask what his MO was for this record, his first. “And I have these great friends who are amazing musicians, and it would be a shame not to have them play and record these songs, that was the short term [MO], it was for me – to be able to look back and say, ‘I did it, I did the album everyone has been asking about… and I’m proud of myself’. “And at the same time, I’d be stoked if people just listen to it and enjoy it, and it’s a bonus if I get any sort of recognition for it, and that’s it.” It’d be a crime against roots music in general if Cardwell were not to receive recognition for My Friend Defiance – bluesy riffs abound, there’s a solid groove that underpins the album, it weaves nicely between light and shade, it grows and powers ahead, often with the same song (‘Freedom Feeling’ is a fine example of this, an epic song) – it’s the album people have been asking about for over a decade, and Cardwell has delivered it.

“Yeah, I’m really, really happy about it,” he smiles. “I feel it’s a strong album, and I feel there’s no filler on there, for me.”

My Friend Defiance is available now via Blind Date Records

WHAT’S GOING ABOUT

Andy McGarvie releases his second album and it’s guitar-driven, blues-tinged, rock-soaked singer-songwriter Americana - straight out of Melbourne.

By Michael Smith

We almost didn’t get to hear Going About This, the new album from Melbourne singer, songwriter and guitarist Andy McGarvie. He just wasn’t sure about it. Ironically, self-doubt is one of the issues he explores on the album, as he admitted to Michael Smith. “I released my first album, Not Soon Enough, in 2016 and when I moved to London in 2017 I had some of this material already written, in bits. Two of my siblings got married a couple of months apart at the end of that year so I thought I’d just come back and stay in Australia for a few months and in that time I got the band together and we went into the studio and recorded some stuff. In 2018, I had to have surgery because I had cysts on my vocal folds. This of course meant that I couldn’t sing in the same way and couldn’t really get across what I’d originally intended with those songs, so to be honest I kind of shelved the record. “Then Fraser [Montgomery], who mixed and mastered it, he contacted me and asked, ‘Hey, when are you gonna finish this record?’ That was at the end of 2019, and so I thought we probably should. I listened to it and realised we could make it work. So, in the time between going back to the UK again and coming back because of COVID, I spent some time finishing the vocals. But I was very close to not being bothered with it, though listening back to it now I’m very glad I didn’t do that. Like so many artists, you think ‘this is terrible, no one’s going to want to hear this, why do I bother?’ blah blah blah. “I’ve said to people before, I used to think good songwriting was from a place of pain or a place of anguish, but in fact good songwriting is from a place of honesty. This whole record is very honest about my transformation as a person over the last few years, and the things I actually care about – I’ve always been political, but I’d never written a political song until I wrote ‘Nobody’s Home’. These things are what’s important to me because I can believe what I sing, you know? And that’s kind of new for me as a songwriter.” McGarvie is quite the wordsmith – in fact, his songs read more like he’s telling little stories, insights into the workings of the heart, rather than doing the conventional “verse/verse/ chorus/middle-eight/chorus” thing – so it’s surprising to learn that when he writes, it’s the music that comes first – but more on that in a moment. At the core of his writing is an exploration of that space between what you think you’re feeling, what you might actually be feeling and what you could eventually be feeling – the tension between past, present and future. “I think that also comes across in the sense that the songs are written at a point where you might be feeling something, they’re then recorded when you don’t feel that thing anymore and you have to bring that feeling back, and then they may be performed again where you are putting on the character in that song even though you don’t necessarily feel that way anymore. So, it’s a photograph of the moment; it’s just the way the photograph happens over, in my case, a couple of years of writing through recording to performing it. There is this tension, as you say, between past, present and future, but I try to detach a little bit from the feeling of the story now, and I treat the story as a feeling that happened at one point and while it may not be how I feel right now but it’s an honest representation of that moment. “I think the idea of hope is an important one, especially when you’re being honest with songwriting. You can come through a moment of real, personal turmoil or tension and you can reflect on it years later, look at it and be able to stand there and internally say, ‘Look at the difference between how you feel now and the words that you’re singing where you are very clearly verbalising what you felt then,’ and to be able to see that difference on a personal level is really cool, a really unique thing that a lot of people might not get the chance to do for themselves. “I write the music first,” he explains, “and then get a kind of sense of what that music is saying to me, mood-wise. The lyrics for me always come second. I’ve always got a rough idea of maybe where I want to go with something, but a song like ‘Going About This’, for example, that started as being a completely different kind of thematic idea and as I kind of sat through that chorus and realised what it was about, it sort of exposed itself as being about me – it’s not about anything else I was trying to write it about – and that then begins a journey – ‘Well, let’s analyse this self-realisation a little bit more, what this phrase that apparently came out of nowhere has brought me to think about.’”

Going About This is available now at andymcgarvie.bandcamp.com

By Chris Lambie As His Bob-ness turns 80, we celebrate a life devoted to The Song. Dylan is one of the most covered artists of our time. Melbourne singer-songwriter Bill Jackson, an avid fan, reflects on the crafting of message with melody. “Back in the Middle Ages, the minstrels and the songwriters went from town to town and they were the newspaper, spreading the news. I think, as songwriters, we’re part of that lineage. It’s important that we don’t become too navel-gazing. There’s enough of that as it is.” The third volume in Jackson’s series The Wayside Ballads tells stories of convicts, shearers, immigrants and soldiers. He says, “Not be so arrogant as to say we’re educating people but making them aware of what life was like.” Over 15 years, Jackson has collaborated with his wordsmith brother Ross, a war historian. “It’s a great relationship to have.,” Jackson says. “Ross comes from a poetry angle without thinking about choruses and hooks. My part is to bend these things into songs and meld them into three minutes as well. I might not change a word, or sometimes just use a line or two or an idea. For the song ‘The Shed’, he sent me a really long poem about our great-great-grandfather who was shearer. It’s almost like trying to put a cracked mosaic or jigsaw puzzle together. To give it some sort of narrative but also make the words attractive and give people a taste of what the life must’ve been like and the hardness of it.” The album opens with ‘Convict Blood’. “It was Important to start the record by asking a lot of questions about us as Australians. I just love some of Ross’s lines like ‘Where did you get that spirit to fight/ Where did you get that rebel streak? You can feel yourself in it.” The Wayside Ballads Volumes 1 and 2 have a different feel to this final instalment. The first was an electric affair produced by Shannon Bourne who also plays on Volume 3. The second represented a string band sound, mostly recorded live in the studio with Thomm Jutz in Nashville. Planned late in 2019, this latest recording saw Jackson and producer/instrumentalist Kerryn Tolhurst (The Dingoes, Country Radio) working together apart – via file sharing and “thousands of phone calls”. ‘That’s Why I’m Here’ represents those who come to our shores from troubled homelands. “Kerryn did an amazing job on that. I’ve been playing that song for four years but a really fast version of it. He gave the song its own personality. His beautiful guitar tremolo line at the end of ‘The Shed’ really pins that song.” Likewise, Tolhurst’s mandolin on the closing bars of ‘Summer on the Somme’ evokes the location. “Kerryn first came to my attention from his work with The Pigram Brothers. I’m really chuffed that he liked my songs enough to work with me. I’ve pretty much had his complete attention for two years.” The pair have all but finished recording another album, quite different again. Guests on Vol.3 are Stephen Hadley, Mischa Herman, Shannon Bourne, Ruth Hazleton, Paddy Montgomery and Greg Field. As with his partner Hazelton, Jackson laments gig plans going awry. He and Tolhurst did get to briefly air the new songs to an audience or two between lockdowns. Of the tale told in ‘The Ballad of Billy and Rosie’, Jackson laughs, “I had to get permission from the family to put that one out. It’s good to keep the stories alive.” Jackson grew up hearing his dad’s Country records. “I started playing guitar at 15 - Dylan, Joan Baez, Donovan. I’ve always liked writers like Guy Clarke and Townes Van Zandt, all the usual suspects. You gravitate to the lyrics, the stories. Even songs like ‘Harper Valley PTA’. There’s a great message in there. Johnny Cash’s album about the First Americans, Bitter Tears. Those people had a conscience. That’s what I love about it.” In 3/4 time, ‘Cut & Run’, Ross’s describes an aging songwriter, tied to his art, passionate about it. “I could kind of see there was something in there about me. That drive to leave something behind. Mischa plays high whistle on it. I wrote the last verse, asking ‘How come we’re still talking about dropping the bomb?’ Since releasing the album, Jackson thought he’d write a song for Dylan’s 80th birthday. “So, I wrote one last night and sent it to Kerryn. There’s a song on Another Side of Bob Dylan called ‘Ballad in Plain D’. Mine is called ‘Ballad in Plain E’.”

The launch of The Wayside Ballads Vol 3 is scheduled for Tuesday September 14 at The Brunswick Ballroom. The album is available through Laughing Outlaw Records.