UNDERCONSTRUCTION

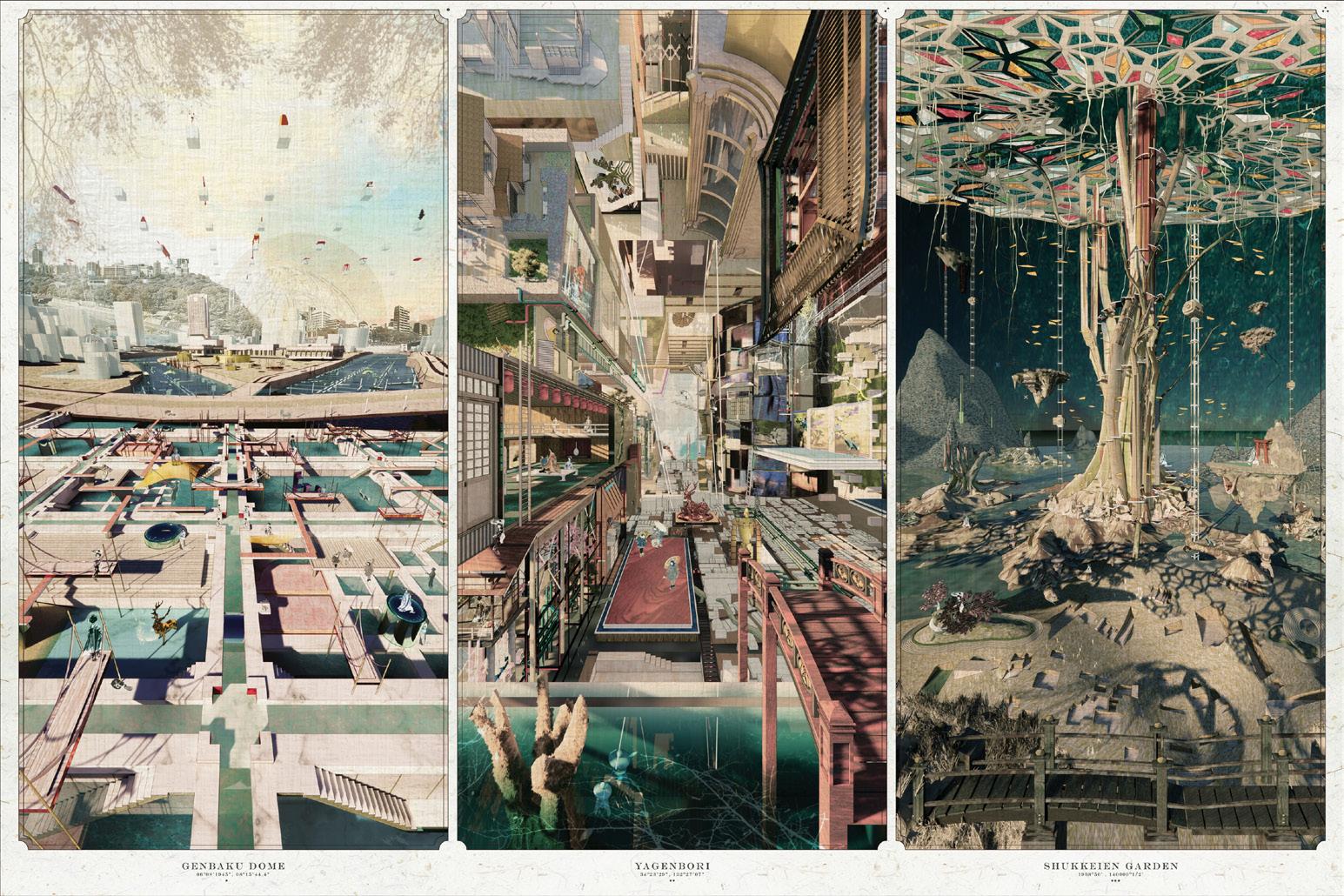

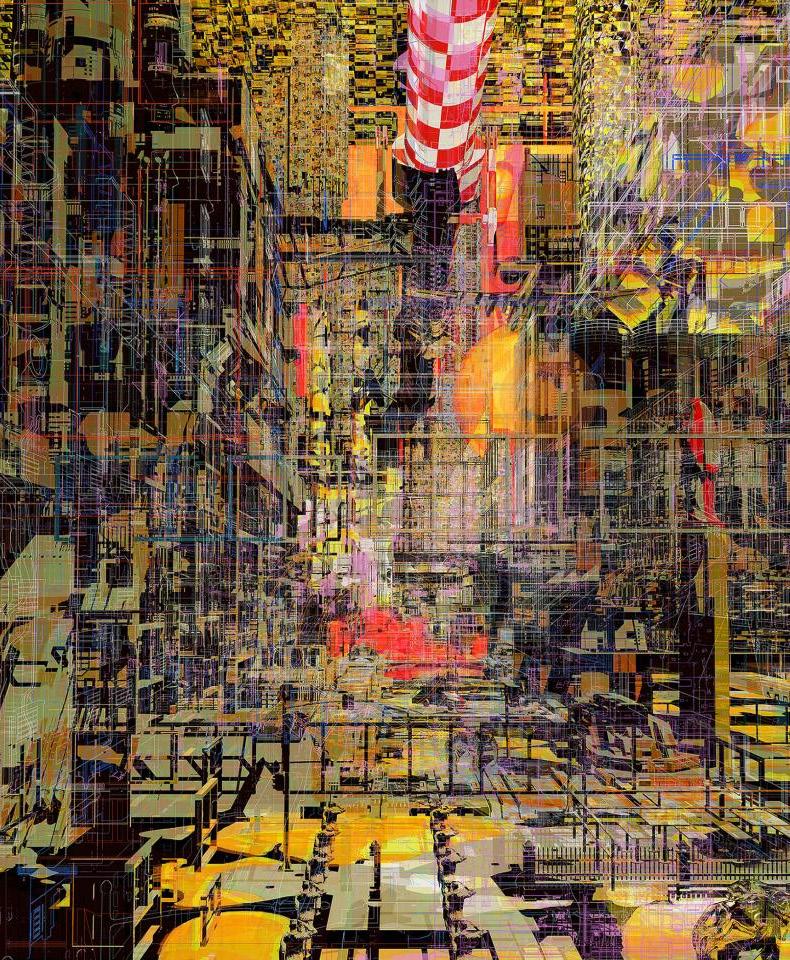

Postcards from an Urban Processor Ink and Watercolor 2005

Postcards from an Urban Processor Ink and Watercolor 2005

by: Petra Kempf, PhD.

Architectural drawings today exist in numerous mediums reflected in the wide range of cultural practices dating back to the fifteenth century. Architectural drawings are cultural vessels for imaginary worlds, physical realities, or the depiction of concepts. They can range from a fleeting sketch capturing an idea to computer generated drawings. Within this realm, drawings exist in numerous forms, unfolding through self-directed acts, independent from real world scenarios; or are of direct purpose towards a built reality. Whether the act of drawing revolves around the communication of preliminary ideas or the execution of a set of construction drawings on site: drawings serve the architect to communicate. Each drawing reveals a discrete process through which irreversible energies are revealed, like the production of a kind of traction between different forces interacting.

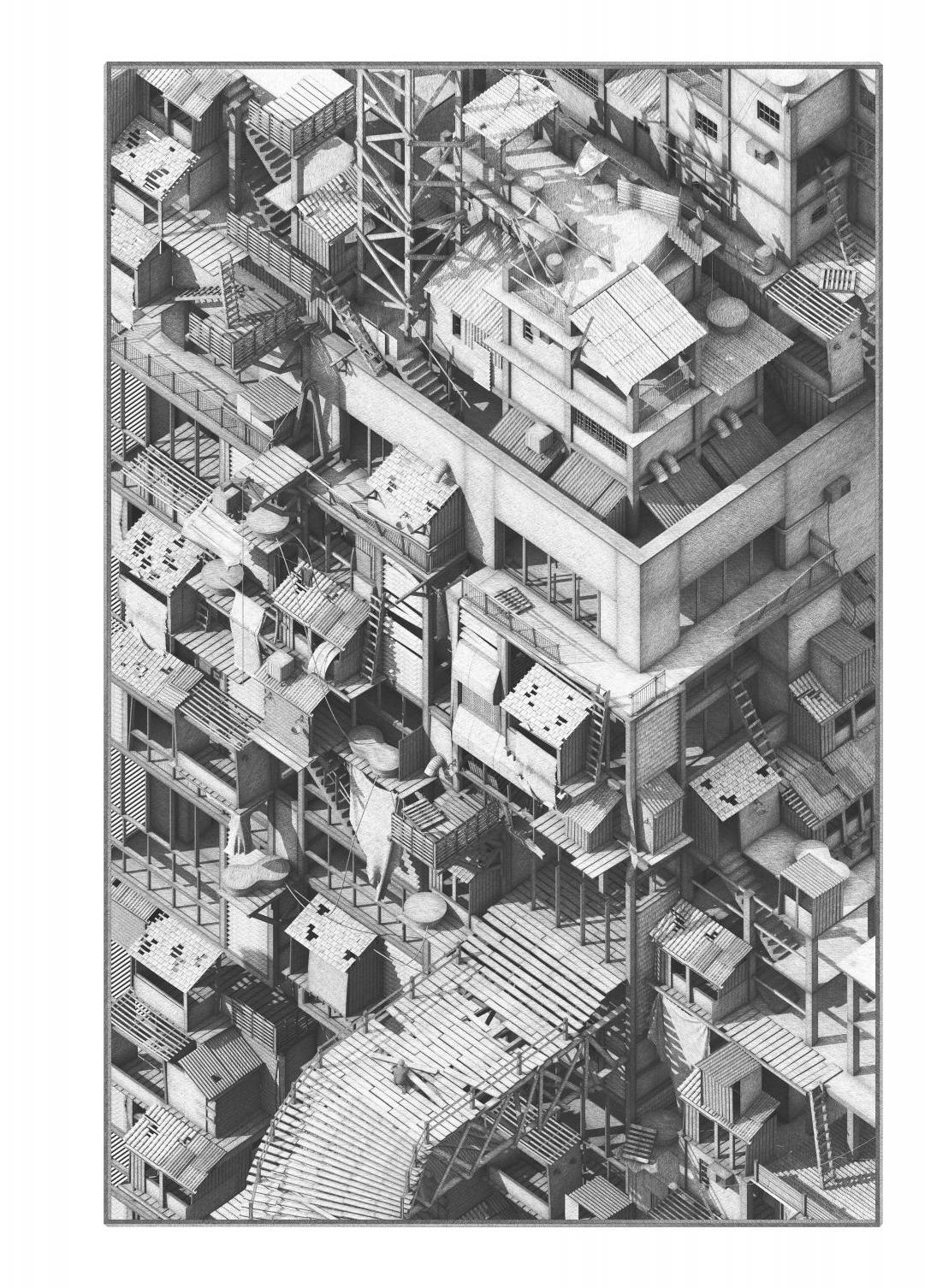

Drawings in this regard provide the linkage between hand and mind, represented in form of a visual script based on clues translated on to a surface; or to use Roland Barthes definition on the act of drawing: “a set of rule governed transpositions.” This form of representation is far from being neutral as each drawing transmits “the means of representation by which it was created.” Analogue drawings are “phenomenal in nature, a synchronous collecting of the hand, the eye and the mind into one purely authored, deliberate and irreproducible act.” In this process the author leaves a residue similar to a palimpsest where lines are drawn and erased to be redrawn again – a continuous process of aligning misaligned lines. As the drawing is giving the viewer a glimpse of a world unfolding – always incomplete – the viewer’s imagination begins to participate in discovering a world.

The notion of architectural drawings as an artistic and experimental expression emerged less than a century ago, apart from the utopian drawings generated in the 18th century, with the most notable examples of Étienne-Louis Boullée, Claude Nicolas Ledoux, and Giovanni Battista Piranesi. The drawings generated during the avant-garde found their expression in pushing the boundaries of ideas, both innovative and radical in their expression, which included not only Futurism, Dada, Constructivism, but also the Bauhaus and De Stijl, among others. They all applied drawings as a critical tool to open the field towards new worlds of exploration.

The experimental architectural aesthetic that applies drawings as means to unfold new worlds are also evident in the dystopian settings generated by Archizoom or Superstudio; the technology driven utopias by Archigram, Future Systems, or the Metabolists, and also the drawings by Cedric Price, Bernard Tschumi, Peter Eisenmann, or the speculative drawings by Madelon Vriesendorp and Zaha Hadid are all testimony for the importance of speculative drawings to experiment and test ideas, techniques, and representation in the architectural field. This also includes Peter Cook’s collage like depictions which challenge the “formal vocabulary of architecture, free from stylistic conventions and constructional limitations.”

Obviously, the act of drawing today take place beyond the analogue as its application found new forms of expression through the relationship to other disciplines, offering alternative perspectives towards uncharted territories. Drawings today unfold in playful and abundantly diverse domains, both through the analogue and the application of digital media. This engagement ranges from the scale of microscopic detail to the application of shock to promote new architectural ideas and spaces.

Architectural drawings have not always been artistic. Prior to the Renaissance the work of the architect was mainly associated with manual labor and the authorship of a building was not linked to the architect as the sole author. Only significantly important structures were designed, predominately through model making and rudimentary diagrams, and the design of a building was executed directly on site through the designation of its location by signifying its key points, which meant “[d]esign literally ‘ruled’ the process of construction from within the manual building crafts.” During that time drawings were seen not to be more than a flat surface onto which shapes were drawn; meaning architectural drawings on paper, which became eventually paramount in architectural and artistic practices, were therefore not readily available at that time. It was in the Italian Renaissance that drawings for the first time became an essential part of the profession as they accurately depicted a three-dimensional world onto a flat surface. This coincided with the growing availability of paper in the late fifteenth century corresponding with a prior invention – the perspectival drawings by Filippo Brunelleschi – which engendered the application of drawing in the making of architecture, allowing architects as well as artists for the first time to plan and precisely depict a proposed building or sculpture through the application of perspectival drawings on paper.

This form of engagement enabled them to fully emerge from the building crafts tradition and allowed the architect to pursue theoretical problems of imagined structures. As architects were fascinated by the precision and mathematical language of proportion during that time, it was the application of measured draw-

ings that allowed them to explore these new worlds. However, despite the preliminary status of these studies, the act of drawing was understood as something important in its own right: it served as a tool to study the formal and technical dimensions of a design. In 1550, Giorgio Vasari commented on the exclusive relationship between architecture and the act of drawing with: “their chief use indeed is Architecture, because its designs are composed only of lines, which so far as the architect is concerned, are nothing else than the beginning and the end of his art.”

As the drawing became an essential tool to the architectural practice, the architect, according to Leon Battista Alberti, was now able “to project whole forms in the mind without recourse to the material” This enriched and affirmed the architect’s engagement beyond the construction of buildings. During this time architects began to theorize architecture in drawing and writing, exemplified by Palladio, Serlio, or Vignola as early examples, and John Hejduk, O.M. Ungers, Rem Koolhaas, or Pierre Vittorio Aureli more recently. Throughout time, critical drawing and writing on architecture in conjunction to building architecture became eventually an integral part of the profession. However, going back to studying the history of architecture since the Italian Renaissance, researching, testing possibilities, and questioning architecture unfolded predominately during that time in drawing and writing before building, which allowed the (artist-) architect to fully emerge from the building crafts tradition.

With the declaration of Architecture as a Fine Art another distinction followed, triggered this time, by the Industrial Revolution, through which Architecture as an aesthetic discipline began to distinguish itself from the discipline of the applied arts, such as fashion, graphic and industrial design. Jonathan Hill claims, this split was induced by how the term design was applied within the discipline, meaning the design of architecture was no longer associated with drawing an idea but drawing appliances. He states: “most people associate design with the newer design disciplines which affects how architecture design is understood. But in the discourse of architects, the older meaning of design, as drawing

ideas, and the newer meaning of design as drawing appliances, are both in evidence.” However, with the conception of architectural design towards “drawing appliances” - to use Jonathan Hill’s words – a shift in perception took place: no longer was architectural work associated with the execution of drawings that were based on an idea coming “from the mind into physical reality,” but an object-oriented product generated by a set of digitally produced parameters, allowing for cinematic viewings through the assemblage of factual conditions generated by digital media.

There is no doubt that the application of digital tools to describe and manipulate a design based on information stored in a cloud benefits the process of developing and constructing complex buildings. Today, architects work with programs such as AutoCAD, Rhino, or Revit, and their projects conform to digital modeling and Building Information Modeling (BIM). While architectural practices operate seamless between hand drawn sketches and drawing in the digital, there are two distinct set of beliefs in the academic realm when it comes to architectural drawings. One group aims to abolish drawing by hand as they believe hand drawings are static artifacts while the other group thinks hand drawings are an essential tool in the education of an architect, as in their mind the emphasize on drawing by hand allow for the ambiguous play of orthographic projections. When it comes to design, it should be noted here, the profession today is predominately focused “on technical competence and acquiescence to commercial and regulatory forces,” while the academy is experimenting with both, the digital code to parametrically manipulate form to describe an object, and the exploration of hand drawings as way to study “implied actions, performances, and effects” to use Kiel Moe’s words. While this debate goes on, the digital work of many architecture students today reveal a prominence of drawing buildings as objects by accepting that drawings are understood as a dynamic set of information rather than the creation of drawings unfolding through designated rules of ideation. This has developed into a “disproportionate emphasis on the image quality of the building and less concentration on the intellec-

tual content imbued in the building through the composition of the drawing.” In addition, the infinite levels of abstraction available; the reminder of the 1:1 scale one is operating in, while trying to orient oneself, often yield towards a form of presentation that lacks the basic trace of intellectual investments towards an appropriate detail and scale—a trace of exploration one finds more frequently in hand drawings. That means, data “is recorded at a 1:1 scale, but the size of the screen image indefinitely varies as the operator zooms in or out to consider various aspects, creating the inability to put them into a perceivable relation to the operator’s body.” While the body remains almost motionless outside the modest movements of a hand moving within the restriction of a drawing pad and screen, the scales of movement through digital media are vast. This shift requires an additional awareness of how to zoom skillfully within the virtual environment; an ongoing back and forth between the scale of a detail to perhaps an entire universe, all displayed on a screen. As one is zooming in and out between scales, layering strategies become crucial in the layout of a digitally generated drawing. This also includes format, layout of a page, and line weight, which become important when drawings need to be printed. Overall, “the accumulation of these commands creates a separate inner monologue chanting not the intrinsic idea of drawing, but of numerous verbalized procedures that must precede the idea.” Once the organizational system is set up, edits and changes can easily be made, leaving however no traces of previous drawn lines if not intentionally saved onto a layer. While the history of a line disappears, digital operations allow for an endless change without any wear and tear on a surface. This allows for the convenient accumulation of information to be deposited, and brought to the fore when needed, while simultaneously creating a depository of some sort. To concur with McGrath and Gardner: digital drawings are “no longer a single crafted artifact, but a body of data from which innumerable drawings can be electronically transmitted, projected or reproduced.” From that perspective digitally produced drawings provide the actions of a hand that “are filtered through the prosthetics of a mouse and keyboard, anonymous actions within the draw-

ing itself as the mouse clicks and the keyboard strokes offer no way to record any specificity or expression of the action.” In this process, one cannot arbitrarily draw a line or curve; only through a set of finite or preconfigured operations can such a line or curve be drawn or manipulated. That means, every line that is brought to life is configured the exact same way. A line drawn by hand always displays a certain kind of uncertainty, despite the application of tools, such as the use of straightedges, compasses, squares, or curvature templates. That does not imply hand drawings are devoid of any accuracy. They are exact within their own means, as they leave “remnants of its construction and development, burdened with the residue of erasures, misalignments and mistakes that offer a glimpse into the process of thought of the author.”

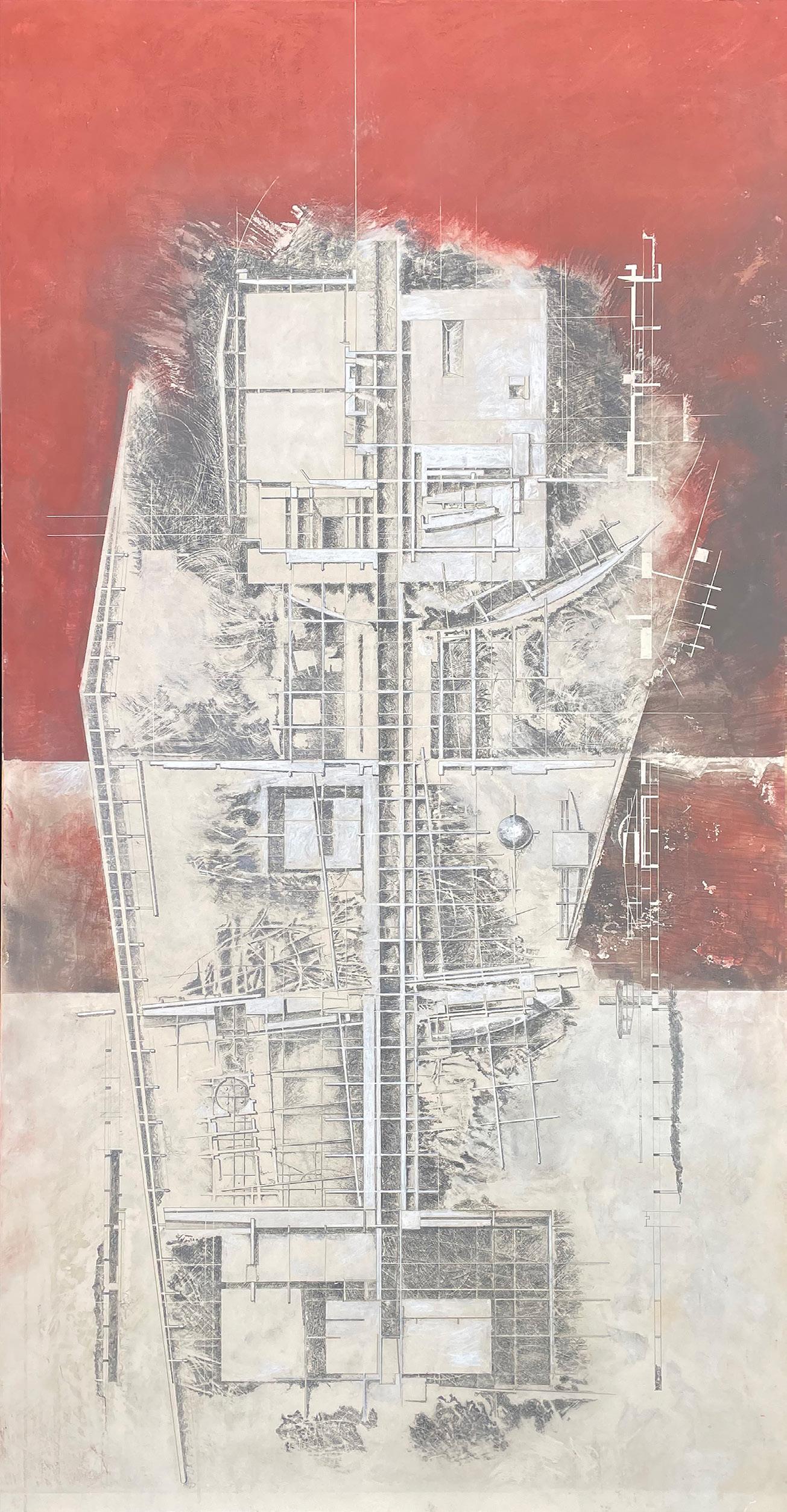

Drawings generated through analogue means, I would argue, are far from being static. They provide a form of interaction that is made possible by the unseen and ambiguous forces unfolding between orthographic projections. That in between is the realm of the interstitial, or so-called threshold region to unfold imaginary worlds. It provides a platform for play—a framework, in other words, through which an evolving and responsive language could develop. Drawings unfolding in that realm, emerge through evolving negotiations of infinite play — a form of play that continues to enrich the concept of ideas at work. Drawings that are generated from a dynamic set of information versus drawings generated in the interstitial realm of a so-called threshold region, could be compared to two different kinds of games: games that are based on finite and infinite outcomes. According to James Carse, “the rules of a finite game are unique to that game”, meaning the rules do not change, while the rules of “an infinite game must change in the course of play.” That means, the rules of a finite game are set to come to an end, while the rules of infinite play are set towards an open end. For this reason, as Carse points out, the rules of an infinite game “are like the grammar of a living language, where those of a finite game are like the rules of a debate.” While “the rules, or grammar, of a living language are always evolving to guarantee the meaningfulness of discourse, the

rules of debate must remain constant.” In this engagement, players participating in the finite game operate within set boundaries, while the players engaged in the infinite game play with the configuration of boundaries, meaning they operate in the interstitial realm of the boundary itself. This is the realm where ideas are born, away from an absolute truth, objectivity, or set boundaries: a liminal platform for unlimited innovation. While construction drawings are considered a depiction of an absolute truth, objective in nature, as they adhere to a universal language of highly specified instructions, drawings emerging from the interstitial realm of a threshold region resemble the construction of a living language. In other words, they are the construct of an ever-evolving grammar. Drawings of such nature are neither here nor there. They reside in the ongoing conversation around an intricate process of becoming. In this process lines are being drawn to only be redrawn, recording a passage through space and time to construct place.

It is therefore critical to keep celebrating the ambiguous forces unfolding between orthographic projections. They provide a valuable playground towards the exploration and development of a design language. As this interstitial realm of infinite play unfolds, the process of these experimental drawings depicts an ever-evolving journey of discovery – a “trajectory that erases and refabricates its path as it moves.” Snapshots are taken, negotiations are conducted, measurements may turn into facts, material surfaces, and connections are being discovered—a line is put into action as another one is overdrawn. Through this lens, the act of creation becomes an inclusive process of world making in which self is as much imbedded in the other as the object is imbedded in the subject.

in Category 2015

By Julien Meyrat, AIA

This past year, the Ken Roberts Memorial Delineation Competition received numerous drawings from dozens of countries and university programs. They are limited to works that are architectural in nature and that are realized in a variety of media, from the simplest travel sketch to nearly life-like depictions of imagined environments. In its fiftieth year, it is the longest lasting and most visible competition of its kind anywhere in the world. Through it all this event has been organized by a dedicated group of volunteers and staff at the Dallas chapter of the American Institute of Architects. How did this event get its start, and in what ways has it adapted over the years? Is it still relevant as more of our drawing is produced digitally and more of the process of its making is automated?

The idea for an architectural delineation competition and exhibit was partly inspired by the late Jack Craycroft’s observation that his firm, Craycroft-Lacy & Partners, relied on producing lots of high-quality renderings to sell design proposals to clients and financial lenders. When Ken Roberts, a young architect responsible for many of these precise ink renderings left the firm, Craycroft realized how important it was to recognize the contributions of area professionals in the art of architectural delineation. This realization would result in the world’s longest-running architectural drawing competition fifty years later.

As AIA Dallas chapter president in 1973, Craycroft reconnected with his former assistant and tapped him to organize the very first delineation competition. Roberts, a native of the small town of Bastrop, Louisiana, was seen as a rising star at the time., having recently merged his own firm Roberts-Savage Architects with Clutts & Parker to form Iconoplex, Inc. With the support of Jim Clutts, the incoming 1974 AIA Dallas chapter president, Roberts led the committee in putting together a very successful event celebrating delineation, receiving up to 120 entries. It showcased dozens of works and testified to the high-level technical mastery in the drawings among young architects in the Dallas-Fort Worth area. Later that year Roberts, who struggled with a chronic kidney disease, passed away suddenly at the age of 34. Promptly thereafter, the AIA Dallas Executive Committee voted unanimously to rename the new delineation competition in his honor. In a written tribute Craycroft concluded, “He’s gone now but his influence will live on in those whose lives he touched—not only in the professional sense, but in the way he met adversity—straight on, without complaint. The Ken Roberts Delineation Competition will be a fitting memorial to this young man who might have walked with the giants of our profession.”

The Ken Roberts Memorial Delineation Competition (“KRob” for short) soon became an annual event that recognized professionals for excellence in architectural drawing. There would be typically three jurors, featuring reputable architects and faculty from the area as well as throughout the country. A mount-

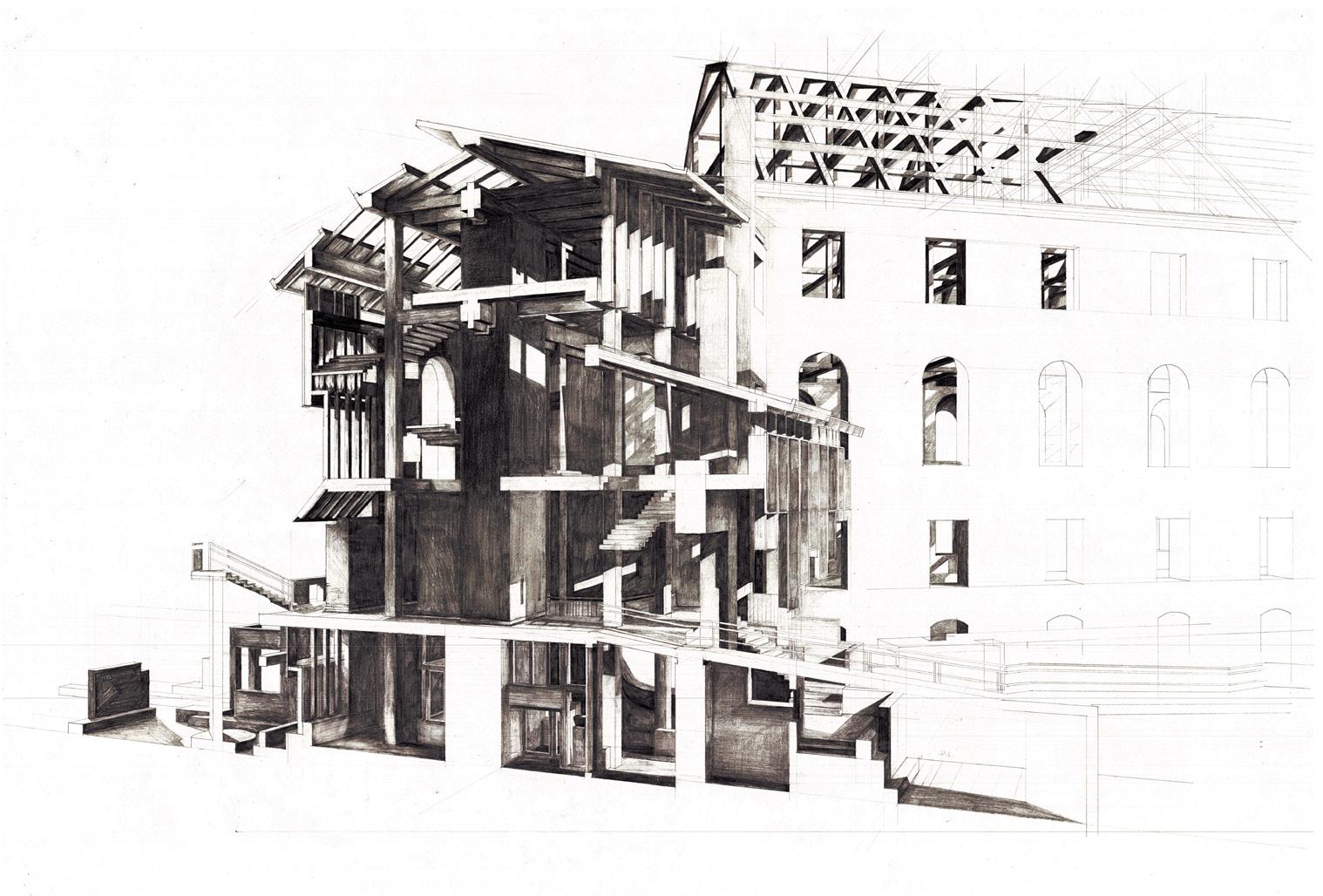

ed exhibit took place the same day as the judging, which would spawn a wider dialogue about the place of delineation in the discipline of architecture. By the early 1980s, the competition was extended to architecture students. Since many of the drawings in school were produced as a part of design exercises the focus of the competition began to slowly shift from the merits inherent in good commercial renderings to the potential expressive qualities of architectural drawings as a conceptual tool. KRob would therefore enjoy consistent promotion from UT Arlington’s architecture program and could expect to receive a generous haul of submissions from both students and professors.

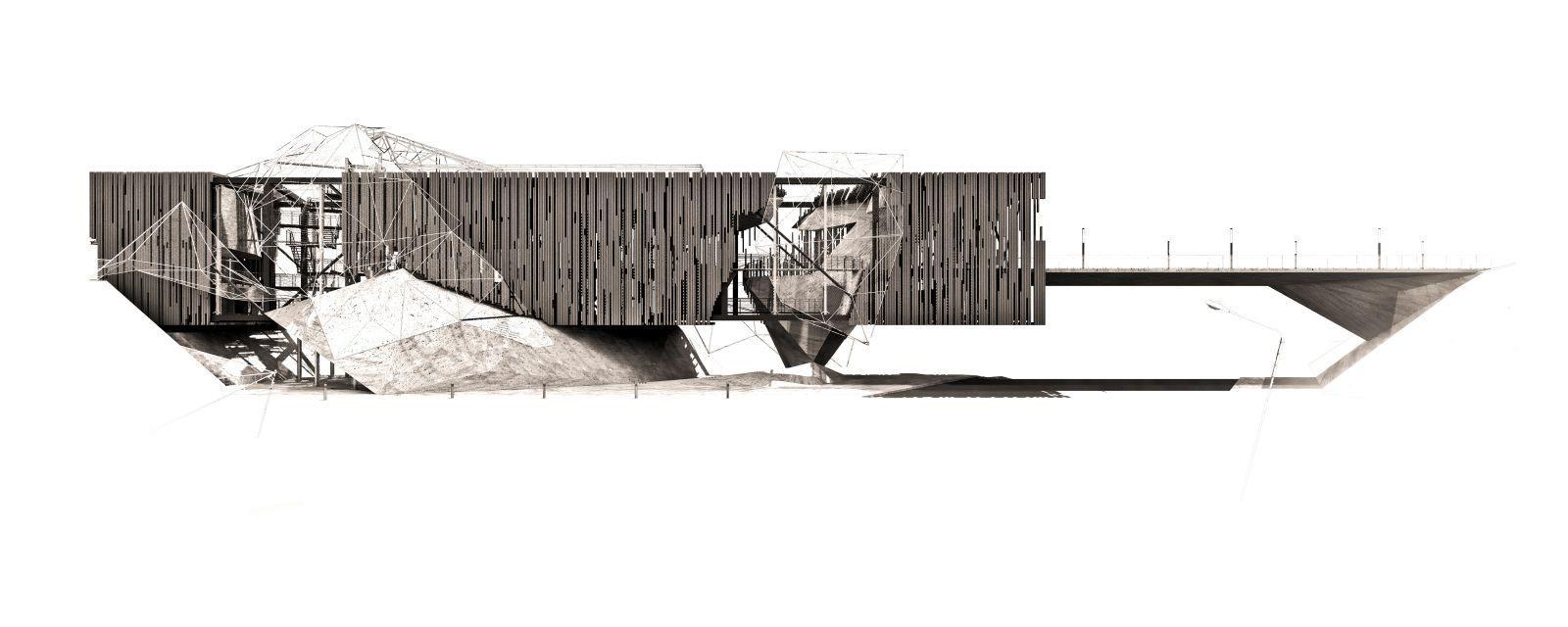

Within the Dallas-Fort Worth region, the Ken Roberts Competition grew into a highly anticipated annual event with the exhibition that followed the judging providing a unique forum for architects, academics, and students to reflect on the role of drawing in the practice of architecture. Organizers had the freedom to create new prizes in response to rising interest in emphasizing previously overlooked aspects of drawing. One example was when by the late 90’s the emergence in the widespread use of computer software was permanently redefining the way architecture was visually communicated. The result was the creation of a prize for all drawings completed using digital/hybrid media. The work could either be a hand drawing manipulated by graphic post-production software or a digitally enhanced view of computer-generated models.

Along with expanding the number of categories, it was just as important to raise Krob’s visibility beyond its local AIA Dallas roots. One way was to ally the event with other adjacent organizations. In 2002, the committee began to coordinate with the Dallas Architecture Forum (DAF) lecture series that feature prominent architects, as well as upand-coming talent, from around the world. The resulting exposure allowed for winners to be announced and their work to be projected on a large screen used for that evening’s featured lecture. This was possible as the featured DAF lecturer also served as one of the competition’s three jurors that reviewed the work earlier that day. A panel discussion

between the three jurors took place, treating the audience to a discussion on the role of drawing before a more detailed presentation of the featured lecturer’s own work.

Another way of increasing the competition’s visibility was through the Internet. Archinect.com, a popular online magazine about the latest architecture news as well as a host for lively forums centered on the profession, supported the event by sending one of its editors each year to serve on the jury. They also generously promoted Krob on their website spreading awareness to a more global audience. And yet, even in an era of the prodigious use of email and ftp sites, the event continued to accept only physical submissions. The inherent time and cost of shipping discouraged many potential participants from entering, causing the number of entries to dwindle into insignificance.

The competition had nowhere to go other than launching its official website, krobarch.com, in 2006. John Hale, who chaired the Krob committee that year, employed his web programming skills to create a robust online home that could upload entries, process payments, and could feature in real time a gallery of winners. It also served as a means for the jurors to preview and rate all the entries more systematically, guaranteeing an efficient use of their limited time. The website proved a dramatic success, with the number of entries rose dramatically that year with submittals coming from across the U.S. and soon after the rest of the world. It received a few tweaks over the years, but overall Krob’s online home has been essential to the competition’s expanded international visibility. Following Hale’s eventual departure, Jeff Windler took over duties of regularly managing the website, updating its code, and enhancing its functionality. He would later apply this functionality to the Dallas chapter’s Design Awards program through their secure online portal.

With the transition to a mainly digital platform, it became apparent, judging from the submissions over the last decade, that the nature of architectural drawing has been dramatically redefined. Technological innovation has put into question the importance of drawing, the tra-

ditional and still primary medium through which architectural ideas are communicated. It has migrated from paper to a digital file that can be effortlessly sent through the internet. This file contains a simulation of a hand drawing, often enhanced by software that can mimic and then surpass our natural ability to manipulate a drawing’s brightness, its levels of contrast, or its clever use of layers. Perspective views are no longer the result of forms generated by two-dimensional construction lines sketched over a page; they are now instead a literal depiction of a three-dimensional model. Drawings are built just as much as they are drawn. The process of creating them has departed from the tactile and direct to the virtual and indirect. The intrinsic physical qualities of the media used has been nearly lost once received by the website. From these realizations above new categories were added to restore the value inherent in physically produced drawings: the Richard B. Ferrier Award for best Physical Delineation, established in 2010 and named after the late UT Arlington professor; and the Kevin Sloan Award for Best Travel Sketch created soon thereafter.

It was Sloan, an esteemed Dallas-based landscape architect and educator at UT Arlington who passed away in 2021, who also helped answer the ultimate question that considers the core purpose of the Ken Roberts competition: what makes a drawing good? In a 2013 interview, Sloan responded by explaining that “A good presentation drawing persuades. A good exploratory sketch converses with its author meaningfully. A good technical drawing constructs. There is a profound conversation that takes place once a drawing establishes a liveliness that makes it instantly relatable. It should therefore not deceive the viewer, masking the architectural idea with sophisticated technique, now made easier with digital tools. Hand drawing, in this way, lends a drawing an imitable authenticity since it is the most direct manifestation of the author’s mind.” Sloan continued, “Michelangelo always asserted that the job of the artist [or architect] is to get the hand to obey the mind.”

This isn’t to say that Krob has forgotten to look forward into the future. As software advances and as computing power resides on the cloud,

more competition categories have been created to capture the work happening in emerging disciplines of 3D printing, animation, and AI-generated images. Still, despite the new sets of technical skills these tools use to automate the traditional drawing process, it is still possible for a jury to look past all of that and identify a successful drawing. Steven Quevedo, professor of architecture at UT Arlington and one of the Krob’s most prolific winners, explains the flaws of relying too heavily on technology. He says, “Technique is only one component of architectural skill. So many renderings with digital technology advance only a pretense for drawing. They seem to be more and more about a specific function made possible with digital programs. Such drawings often lack poetry and spirituality. If a drawing is just about itself and technique, it can be engaging, but a great drawing has many layers that go beyond technical skill. The drawing is an artifact of the architectural design process, so it contains within it the spirit of the work of architecture it conveys.”

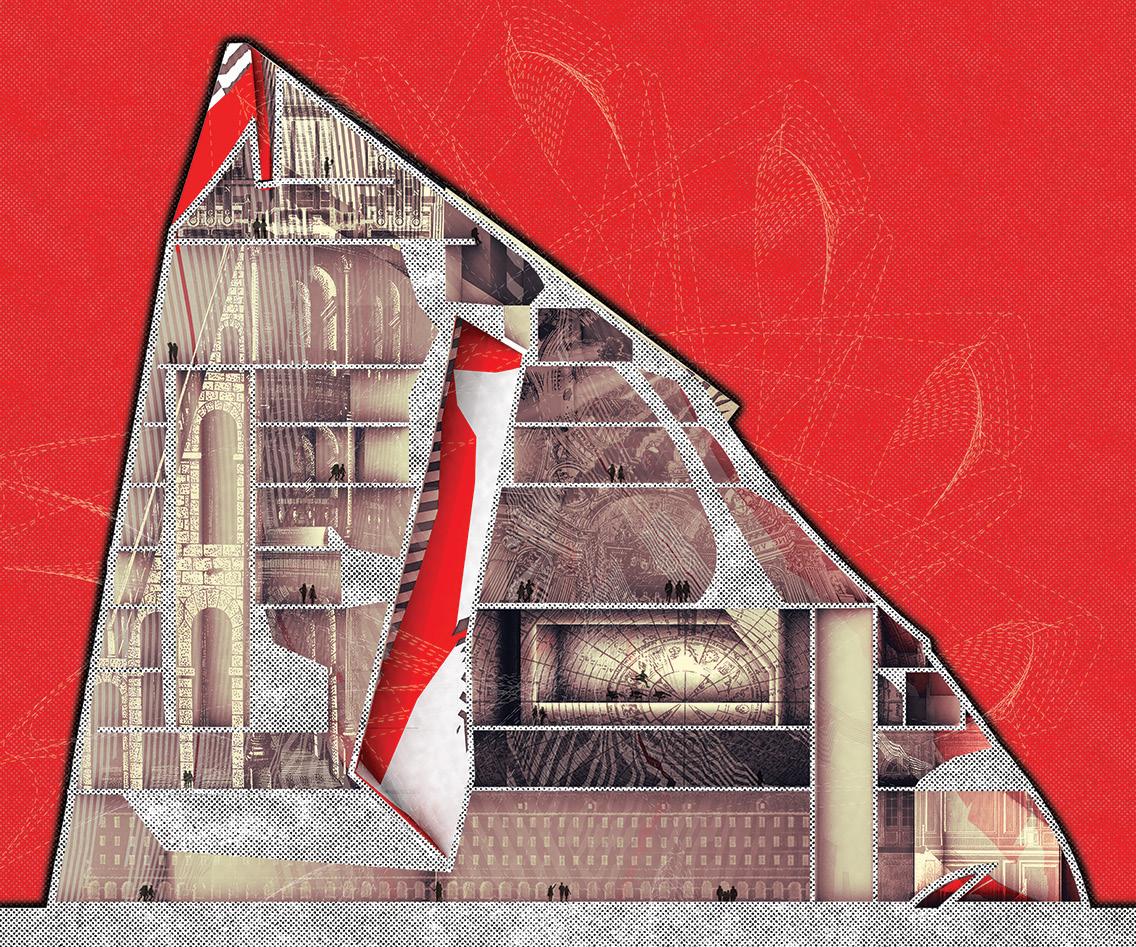

Whether the work is a simple sketch on paper, a digital rendering or an animated video, what the Krob competition reminds us year after year is how important it is that it tells a compelling story. Many of the most successful submissions depict environments full of atmosphere, rich in texture, and establishes a mood with sensitively controlled lighting and colorways. They imbue in the work an emotional resonance that captivates the viewer. “The narrative or story a drawing tells is the deep structure,” Kevin Sloan concluded, “and this aspect has the capacity to draw the observer into the picture and get the head involved. A picture has always been worth a thousand words.”

The past fifty years has witnessed a transformation in the way we practice architecture, and the Ken Roberts Memorial Delineation Competition has followed the changes taking place to its core discipline that lies at its core: drawing. Krob’s website gallery of past winners and finalists serves as a valuable window into the evolution of drawing and the expansion of artistic expression that has accompanied the digital revolution. And still, the competition’s core identity as an event that seeks to highlight excellence in how our

designs are visually communicated remains unchanged. Most importantly, Krob continues its commitment acting as a unique nexus where fellow architecture professionals and students from the local community and around the world can gather to celebrate, and be inspired by, the art of architectural drawing.

Entrant Name/Studio Award, Year

Entrant Name/Studio Award, Year

Entrant Name/Studio Award, Year

by: Alejandro Borges

In the constantly evolving world of architectural representation, hand-drawing remains an essential and irreplaceable tool, embodying a revolutionary perspective that surpasses technological trends. As a means of architectural representation, hand drawing is not only a lasting technology but also a groundbreaking alternative to the advancements of our time. By examining the past, understanding the present, and envisioning the future, it becomes clear that hand-drawing is not merely a nostalgic remnant of outdated practices but a crucial necessity for the education of architects.

There was no more direct way to translate ideas from the architect’s mind to paper than through handdrawn sketches and diagrams. From the calligraphic plan drawings of Vitruvius to the sketches of the Renaissance masters, architects were believed to transfer their ideas through the direct connection between their brains, hands, and ultimately, the diagram. Arguably, architects during this era created the most powerful and intimate representations of ideas using nothing more than their hands, a pen, and ink, free from the mesmerizing yet often deceptive nature of contemporary digital interfaces.

The practice of hand-drawing brought an additional layer of comprehension to architectural education. Through the guidance of hand-drawing and drafting, students not only acquired technical skills but also developed a profound engagement with design. Hand-drawing was not just a medium but also a cognitive exercise, but a way of thinking, iterating, and representing that imagined space for the exploration of ideas.

In today’s digital era, there is a clear emphasis on the transparency and accuracy provided by computer-aided design and three-dimensional modeling. However, amidst this technologically driven landscape, there is a radical perspective that highlights the enduring significance of hand drawing. While digital platforms offer efficiency and consistency, they often lack the authenticity and immediacy that are characteristic of hand drawn sketches.

Hand drawing serves as a counterbalance to the digital environment, offering students a tangible connection to their creative instincts. The act of holding a pencil and physically engaging with a drawing surface allows for a direct and personal relationship with the design process. The hand drawn line becomes a tool that maps the author’s innermost thoughts and emotions. This radical viewpoint asserts that this tactile engagement is crucial for fostering a profound understanding of form, proportion, and spatial relationships.

Moreover, hand drawing encourages a sense of authorship and distinctiveness. In a digital world full of generic images, hand-drawing is a way to find a voice, characterized by mistakes and eccentricities that bring expressive richness to architecture. This defiance against digital conformism is a radical act in itself, championing diversity in representation.

The question of representation is not one of “either/or,“ referring to the dichotomy of digital and analog, but about a more inclusive “hybrid” based on taking advantage of their particular strengths and specificities.

Hand-Drawing as a Catalyst for Innovation

Envisioning the future of architectural education, the radical stance upholds hand-drawing as a catalyst for innovation. As technology continues to advance, the symbiotic relationship between analog and digital methods becomes increasingly vital. Integrating hand drawing into a curriculum equips students with a versatile skill set, enabling them to navigate the ever-changing technological landscape with agility.

Moreover, hand drawing fosters a deeper understanding of the design process instilling a sense of responsibility in architects to thoughtfully engage with their creations. In an age where the immediacy of digital tools can lead to hasty decisions, the radical vision contends that hand-drawing serves as a contemplative practice encouraging architects to reflect on the consequences and intentions embedded in their designs.

The travel sketch is such an essential tool that it cannot be substituted by a snap on a camera phone. When we take a photo, we have a limited understanding of the space or object photographed. When we take the time to sketch a space or a facade, for instance, we must analyze it. understand its parts, proportions, and relationships. The hand sketch becomes an analytical tool for learning.

The state of drawing in architectural education when viewed through a radical lens, reveals the enduring significance of hand-drawing. Beyond a mere pedagogical choice, hand drawing emerges as a radical necessity, preserving the craft, tangibility, and individuality that define architecture as a discipline. The act of drawing by hand remains an essential conduit for nurturing the minds and hands of architects, ensuring they carry forward the legacy of thoughtful, innovative, and deeply human act of design.

Entrant Name/Studio Award, Year

Entrant Name/Studio Award, Year

Entrant Name/Studio Award, Year

Entrant Name/Studio Award, Year

Entrant Name/Studio Award, Year

Oklahoma State University

Professional Hand

Delineation Winner 2015

by: Moh’d Bilbeisi

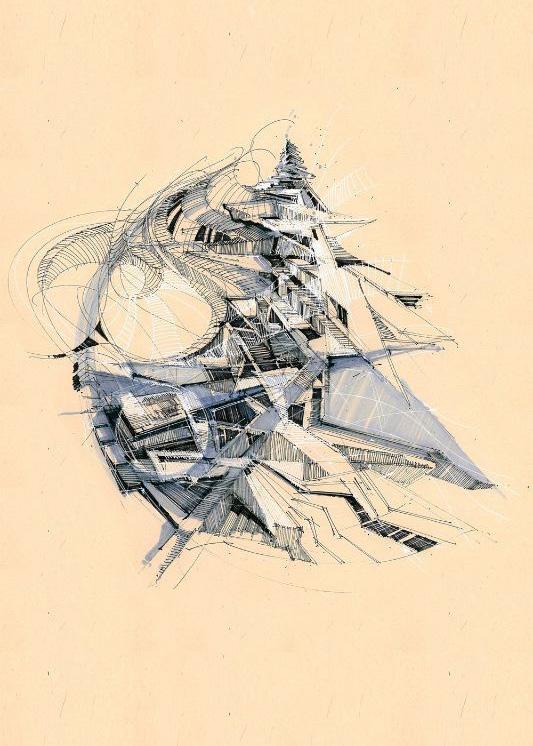

It is rather strange write about dreams as a precursor to sketching anddrawing. I spent half a decade investigating the phenomenon of sketching and to my surprise, the mystery of sketching became clearer. Why do we do it? ell, it’s because we love to dream. We are favored by Morpheus and we don’t know why! We love to dream and many of us are in a state of perpetual dreaming. We see images in our heads and since we can’t speak while dreaming, we sketch. The more we dream, the more we master sketching. It isn’t always about what is there, sketching is about revealing what is not there. It is removing what the Sufis call, the “Hijab” ... the veil, the Smokey Barrier that can only be revealed to the initiated, the ones who spent years upon years sketching, the masters.

Sketching is a natural trait that humans perform as an extension of their humanity. It doesn’t go away. Artists document their life experiences, both real and unreal alike, through sketching.. They visualize it then project it in their fertile minds. They interrogate, they question, they delete, add, and substitute. There is also a mixture of fear and confidence. There is time but how do they retard it? All of a sudden, intuitively, slight vibrations of the hand commence then a barrage of quick, loose,

and intuitive strokes emerge. They are not just visual lines, but rather visceral lines racing through the page, straight, curved, continuous, dashed, seen, and unseen. What is in front and what is in the back? Where is the sun and where is the moon? Where are the shadows and what is in shade? For them, the sketch is alive and positively active. It starts and does not want to stop. They add more lines, more dots, more scratches, and all of a sudden, the sketch becomes alive and it starts to breathe... to speak and to interact with the sketch artist, challenging her to further the inquiry, to reveal more, and to seek the truth about its ontology. It is ultimately about the dream.

I am a Professor and I profess that a good sketch does not just record, it reveals. It has a voice, so it speaks, whatever language you may think of, and more. Sketching is not dead and will never die. A complete sketch however does have a beginning and it has an end and just like all wonderful dreams, good and bad, they eventually end.