Tomasz Machciński

Tom Wilkins

Tomasz Machciński

Tom Wilkins

Tomasz Machciński —

Tom Wilkins

Essays by Agata Pyzik, Christian Berst, and Sébastien Girard

Tomasz Machciński

Essays by Agata Pyzik, Christian Berst, and Sébastien Girard

Tomasz Machciński

Tomasz Machciński

Tom Wilkins

Tomasz Machciński

Tom Wilkins

Essays by Agata Pyzik, Christian Berst, and Sébastien Girard

Tomasz Machciński

Essays by Agata Pyzik, Christian Berst, and Sébastien Girard

Tomasz Machciński

Holly came from Miami, F.L.A.

Hitch-hiked her way across the U.S.A.

Plucked her eyebrows on the way

Shaved her legs and then he was a she

She says, “Hey babe, take a walk on the wild side”

Said, “Hey honey, take a walk on the wild side”

Lou Reed, Walk on the Wild Side

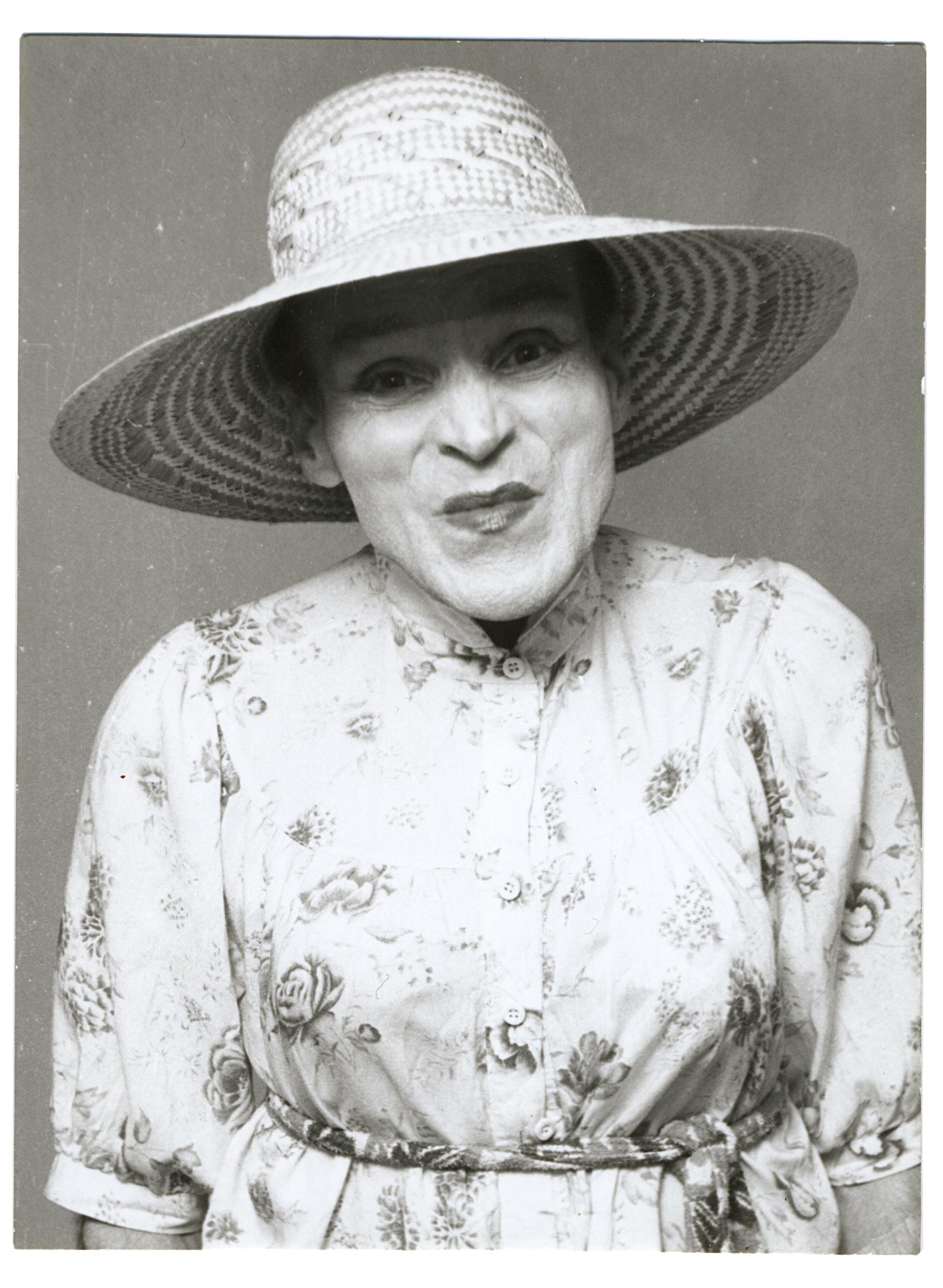

It is hard to imagine anyone like Tomasz Machciński existing in the coarse reality of the Polish People’s Republic, the predecessor, between 1947 and 1989, of the modern-day Republic of Poland. From today’s perspective, the PPR seemed hopelessly uniform as to the roles to which men and women were expected to conform. Gender was under constant, invisible political scrutiny. Looking at the typical iconography of People’s Poland, especially as fixed in the mind of the popular culture, one sees a place where gender roles were starkly defined and painstakingly divided. There were only very masculine men who smoked the strongest cigarettes, drank vodka, and were intensely patriarchal—the women were otherworldly and feminine, in floral dresses, their hair done up; or forceful matriarchs, such as the popular actress Alina Janowska; or sexy vamps like Kalina Jędrusik. Even if there were fleeting deviations from the rule, it was a world in which any diversion from the fixed turbo-heterosexual norm was considered an unsavory anomaly. Boobs were expected to bulge coquettishly, and moustaches gleamed with a gallant shine.

If this strictly gendered world allowed excess, scandal, overabundance, and anomaly, it was mostly under the guise of comedy. In the popular

comic film Man – Woman Wanted directed by Stanisław Bareja (1973), for instance—which one could call the Polish Tootsie —the main character, the art historian Wojciech Pokora, in hiding after being falsely accused of stealing an artwork, assumes the guise of the housekeeper ‘Marysia’ and discovers the charms of womanhood. In the popular 1980s TV series Co-Drivers Ewa Błaszczyk is featured as a sexy butch with tiny mustache; excursions toward crossdressing and small on-screen transgressions occur. Most curiously, the world of art also remained surprisingly gender-conservative. Artists were consumed by formal experiments, and the mainstream had no room for someone like Machciński. It’s no coincidence that attempts to categorize these artists are taking place only now, two decades into the twenty-first century.

Machciński exists a bit on the margins of all the above: as an artist, he remains outside the scope of art history, particularly in its official and professional expression. Aside from a few episodes, such as the Kalisz show late in his career, in 1987, and several group shows in provincial Poland, he was entirely absent from the recognized world of art. Still, he is unmistakably a product of his time and the distinctive queer reality of People’s Poland, not least because he was a child of war. Machciński was born in 1942, and his mother died of tuberculosis two years later, the very same year that his father was murdered in the Nazi labor camp in Pomiechówek. As I gradually learned more and more about Machiński’s life, his biography struck me as suspiciously similar to the film The Case of Bronek Pekosiński, (Przypadek Pekosinskiego, 1993), written and directed by the Polish experimental filmmaker Grzegorz Królikiewicz, about a child born in a concentration camp. He was saved when someone threw him over the camp fence, but his spine was badly damaged, and as a handicapped, nameless orphan, he existed wholly at the mercy of the communist welfare institutions. He was assigned the fictitious birth date of July 22, the beginning of communist Poland.

The adversities Machciński faced during World War II are likewise tragic and dramatic, and yet what struck me in his life story was his amazing vitality, resilience, and creativity in the face of his dire circumstances. In the early postwar years his life was extremely difficult. He contracted bone tuberculosis, a terrible disease that required that he be placed in a hoist and remain bedridden in a hospital for several years, after which he had to learn how to walk again.

It was then that the second-rate Hollywood actress Joan Tompkins spotted him in a book about war orphans and wished to become his “pen mother.”

Although Machciński‘s illness stunted his growth and seriously damaged his posture, he managed his existential baggage quite well, regarding his body as a challenge, not a disability. He remained very physically active throughout his life: he exercised, rode horses, and climbed trees. In a private conversation with me, Katarzyna Karwańska, the curator of his archives, coined the phrase “non-normative body,” an apt articulation of Machciński’s physicality and how he “worked through” it.

After leaving the orphanage, he moved in with a Ukrainian man he called “Grandpa,” who became his first role model. As a young man Machciński worked at the Office Technological Institute in Kalisz. He obtained his first camera, a Soviet-made Smena, in lieu of a payment for repairing a watch. He learned photography on his own, starting with the basics. A shoe balanced on a windowsill served as his tripod.

As he admitted in interviews, it was all just a joke in the beginning, crossdressing just out of boredom, for fun. In time, this pursuit grew increasingly elaborate and conscious. He created the scenarios in waves, over the summer, when he moved to his cottage and had time to experiment. The isolated nature of this endeavor and the solitude in which he pursued it is striking.

In The Polish People’s Republic, the gaze of power penetrated much deeper than merely the public sphere; it invaded as well the private sphere, which it attempted to draw back into the official, scantioned mode of behavior. Yet the test of “officialdom” was not an exclusive characteristic of communist or authoritarian regimes. In his essay on Andy Warhol,1 the American scholar Jonathan Flatley writes about “giving face,” by which he means the way Warhol put not only various pop objects, such as the Campbell’s soup can and the Coca-Cola bottle, but also his own likeness into the public world, possibly helping to destigmatize homosexuality. If these quotidian objects could exist outside the commonplace, a gay man such as Warhol himself could also exist on the outside. Pop Art began as the conception of a group of insiders who perceived certain elements of the world that had previously

gone unnoticed in art, and placed them within art’s realm, making them objects of the depicted world. Warhol “gave face” to Coca-Cola as much as he gave face to his previously invisible homosexuality (Warhol being a closeted gay man in an as yet unemancipated world).

However, before we compare this strategy of making-visible by a queer artist such as Warhol with Machciński’s practice, it deserves mentioning that based on his own statements, Machciński seemed thoroughly heterosexual. Despite his sensitivity to the feminine side of manhood, various statements made by the artist, particularly in his unpublished autobiography, reveal a great deal of interest in the opposite sex: “I was adept at drawing naked ladies,” for example, or “I attended an adult high school, but I was too fascinated by the female students to ever graduate.” 2 It seems that his love for performing women was a reflection of his love for women themselves, and autoeroticism played a major role in his work. Even though Machciński was not a queer artist, his strategy could be compared to Warhol’s “giving face.” Machciński’s work, too, gives face, teetering on the brink of, and often falling into, narcissism. As Witold Gombrowicz wrote in the opening passage of his Diary, “Monday. Me. Tuesday. Me. Wednesday. Me.”

Machciński wrote, “I saw this TV show where people dressed up as famous artists. It was grotesque. There’s no deception in my work. I am these characters: an athlete, a priest, or Jesus. But you have to see it to believe it.” 3 Can the ease and, more significantly, the eagerness with which the artist assumes these characters be explained by his desire to escape his unpleasant, difficult, and oppressive circumstances? Camp is not a polite strategy; it is not simply a process of “working through” anything. Machciński wasn’t sublimating by assuming his roles; he was creating a parallel world to that of People’s Poland, one where he could write his own rules.

Camp’s essence is the aesthetic of too much rather than too little. It overuses normativity, exuding its excess. The scholar Justyna Jaworska calls it a “perfidious spoiling, combined with an affectation and a particular kind of comical seriousness. Even though camp is mostly completely self-aware, it is also possible for camp to be ‘naive’ or unaware.” 4 In her monumental essay “Notes on ‘Camp,’ ” 5 Susan Sontag stressed how camp is not a style ascribed to

particular era, but is ahistorical, yet with the tendency to emerge in moments of crisis or breakdown.

Machciński was driven by a desire to reunite with his absent mother: his biological mother who died when he was just two, or his Hollywood mother. Deprived of all family from infancy, perhaps Machciński desired to personify not only his mother, but also his father, brothers, and sisters—practically everyone, in fact. He became an actor who performed all roles, his own significant other.

Because Machciński was a heterosexual man, his practice does not neatly align with camp’s characteristic queering strategies or excess, but he employs them nonetheless. Always excessive, camp makes references to exaggerated and old-fashioned styles, while resisting irony and self-irony. This is in keeping with the seriousness of some of Machciński’s performances, and while he had no certainty his work would be seen or admired by others in the future, he certainly desired recognition.

The method and aims of these photographs differ enough from those of gay camp to place them in a different category, one more akin to the camp practices of heterosexual women. One could say that Machciński, who began his career in the 1960s, remains a part of the counterculture, which had always seen its activities as situated in and reacting to the social world, without the individualism and alienation typical of contemporary art. Machciński operated in a preemancipatory world, though one that postdates the ideas of the 1960s New Left, namely individualism and identity. In the context of People’s Poland, what he did was deeply and utterly eccentric, untamed, marginal, and palpably dangerous, because it placed him under constant threat of being deemed deviant or abnormal.

Camp in the 1980s gradually lost its subversive nerve, its nonheteronormative, “negative” associations. It became something “cool,” and thus normalized. But Machciński remains subversive in exposing disability, which still does not have a place in the mainstream. On the one hand, the artist uses glamour, especially in his feminine portraits; on the other, he exposes its shortcomings, never fully polishing the image. If there’s makeup, it’s by no means there to cover imperfections—which are always evident. A flawed Lolita with crimped hair exposes her damaged teeth and wrinkles. The “undoing” is always there. Machciński plays for both teams.

One of the reasons Machciński began his cycle was, as noted, his need to unite with his mother. But there’s more to it. The artist created a project so big, especially compared to his everyday existence, that it has the largerthan-life features of a total work of art. The author meticulously prepared for his work: he visited libraries; read and studied art books, paintings, and the biographies of those he impersonated; and finally, as a result of a long-term relationship with them, in a sense he became them. “I am these characters: the athlete, the priest or Jesus.”6 One could call these works a performance that begins at the library, continues in the home makeup studio, and culminates with the photographic image. The artist provokes us with his nonnormative physicality. In one picture Machciński poses as the devil, his horns fashioned from egg cups, and the rest achieved by just makeup (his lips vividly painted, a lipstick stroke dragged across his jaw). This emphasis on the nonnormative seems to be a deceitful sort of camouflage because there’s no way a single detail about this depiction was accidental.

The Devil is just one of thousands of Machciński’s portraits, but it is distinguished by its shock value. As banal as it may sound—although it is anything but—Machciński used photography to overcome his body and his living circumstances, by fantasizing about being someone else. His primary visual source was cinema, especially old Hollywood movies. Another source for him came from being a hippie, which meant he encountered and participated in the counterculture.

I can identify a simple, yet complex emotion in Machciński’s work: wounded manhood, an unrequited love of his mother, the death of his birth mother, coming to terms with the fact that however he might try, he wouldn’t be a classic masculine man. I thought of this as I returned to Sontag’s essay on camp, where I encountered this sentence: “What is extravagant in an inconsistent or an unpassionate way is not Camp. Neither can anything be Camp that does not seem to spring from an irrepressible, a virtually uncontrolled sensibility.” 7

One of the main reasons I started referring to the artist’s work as camp is that it was a labor of love, not a product of pure intellectual calculation,

that led him to decide that he would perform an artistic gesture. The way Machciński talks about his work and its role in his biography and identity, particularly his assertion that assuming a role entails truly becoming that person, all proves that this is no mere masquerade, no donning of masks, but quite the contrary: the nitty-gritty of life.

Machciński becomes characters living many lives and biographies at once. He chooses personages from all periods and registers. He’s attracted by fame and glory, but also perversity, strangeness, and eccentricity. He delights in the freedom of the possibility of assuming various identities. Even if it’s a game, it’s a game in which everything is at stake.

—Agata Pyzik1. Jonathan Flatley, “Warhol Gives Good Face: Publicity and the Politics of Prosopopoeia,” in Pop Out: Queer Warhol, ed. Jennifer Doyle et al. (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996), 101–33.

2. Tomasz Machciński, unpublished autobiography.

3. “Szkoda mnie zakopać.” Rozmowa z Tomaszem Machcińskim, Dwutygodnik, https:// www.dwutygodnik.com/artykul/6421-szkoda-mnie-zakopac.html, accessed: September 16, 2020.

4. Justyna Jaworska, “‘Kłir’ i obraz słaby w filmie Hair Marka Piwowskiego,” Praktyka Teoretyczna 2019, vol. 32, chapter 2, https://pressto.amu.edu.pl/index.php/prt/article /view/19356/19124, accessed June 22, 2020.

5. Susan Sontag, “Notes on ‘Camp,’ ” Partisan Review 31, no. 4 (1964): 515–30.

6. “Szkoda mnie zakopać,” accessed September 16, 2020

7. Susan Sontag, “Notes on ‘Camp,’ ” p. 7. https://monoskop.org/images/5/59/Sontag _Susan_1964_Notes_on_Camp.pdf, accessed March 25, 2024.

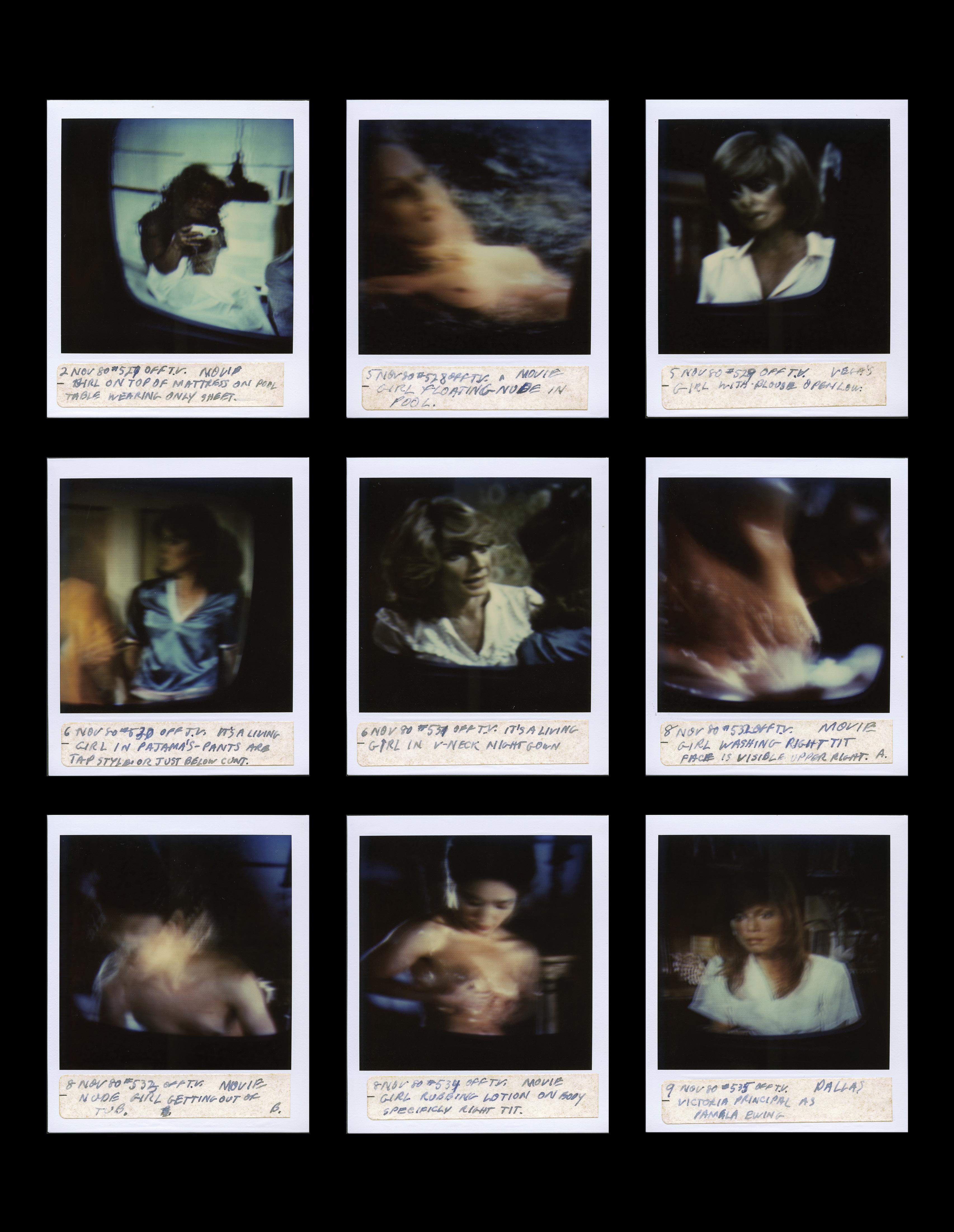

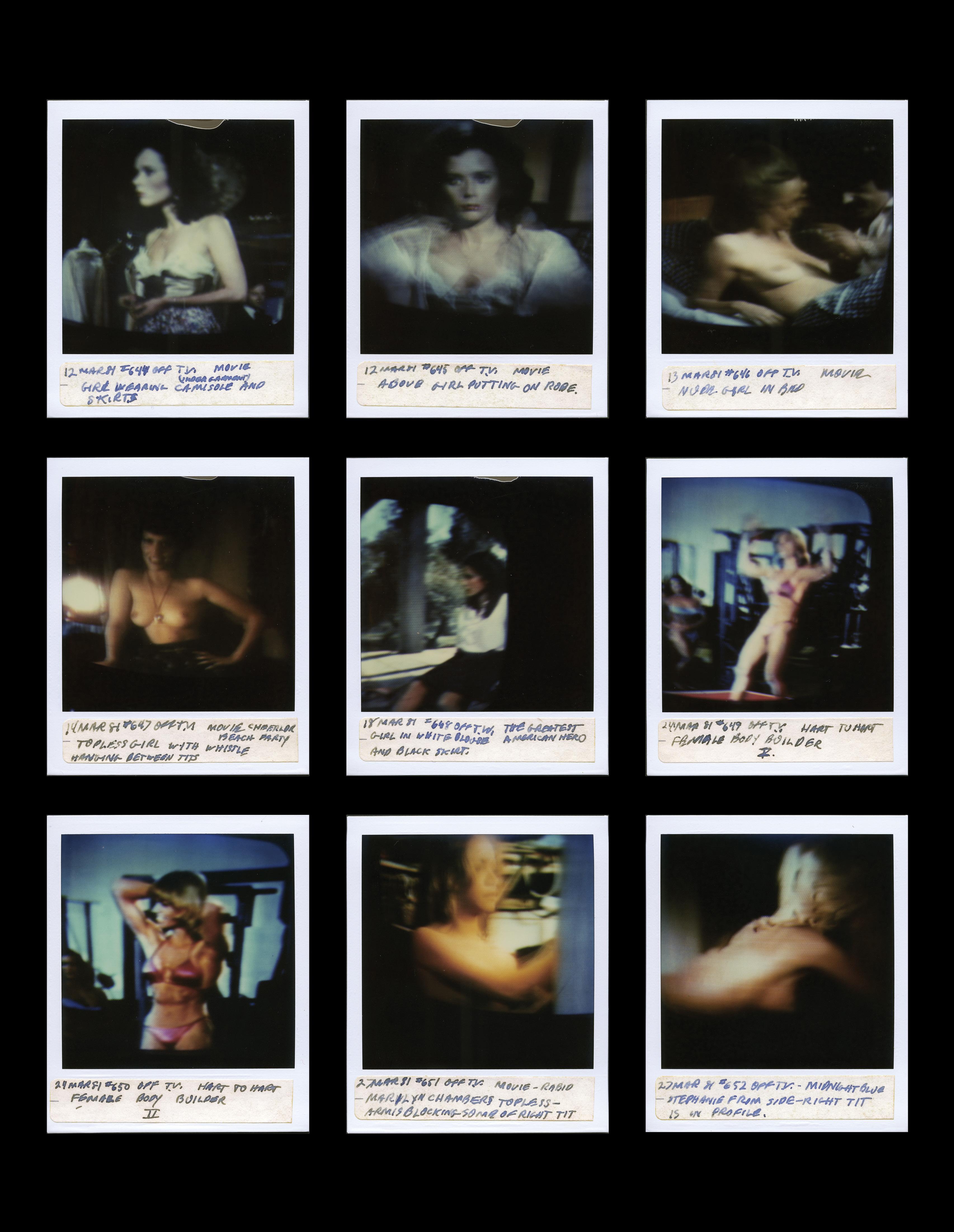

Tom Wilkins’s series of television image captures was created between 1978 and 1982 in Boston. The series invariably features women, with one exception: a self-portrait of the artist as a woman. Who was Tom Wilkins? This is the question that Sébastien Girard has been trying to answer since 2011, when he acquired the 911 enigmatic Polaroids, reproduced in the book My Tv Girls, which he published in 2017. We know very little about Wilkins. He is believed to have lived from 1951 to 2007 and resided in Boston—as evidenced by other more personal Polaroids. His TV Girls, both candid and raw, illustrate how the small screen—and American society as a whole—was shaping the image of the desirable woman at that time. Wilkins also raises fundamental questions, ranging from the construction of identity to the sublimation of desire.

Through these images of female subjects, which elevate them to the status of icons, Tom Wilkins simultaneously reveals and conceals himself, leaving us with the bluish beauty of this captivating collection of photographs. With the self-portrait that concludes this series, Wilkins becomes a subject of his own search. Captured in a mirror, he wears a bra, and his face is hidden by the camera. This cross-dressing, as trivial as it may seem, reveals a profound need to escape gender assignment, by using the societal stereotypes that define femininity.

Since Horst Ademeit, it has been observed how the advent of the Polaroid photograph freed the most scoptophiliacs (those who desire to look rather than actually engage in sexual acts). Fully self-operated in producing prints, and thereby offering the immediate delight of its photogenic “prey,” the Polaroid has consequently established itself as a vector of instant pleasure. Wilkins’s fervent quest for a feminine ideal allows him to create, through his snapshots, an extremely reassuring world steeped in the illusion of becoming a woman.

—Christian Berst

In 2007, Tom Wilkins passed away at the age of fifty-six in his Boston home. Four years later, the executor of his will sought the services of a specialist in Barbie dolls and toys to assess the unexpected inheritance he left behind. Wilkins’s house was filled with all sorts of objects: papers, magazines, catalogs, DIY materials, clothing, lingerie, countless toys, scale models, military dioramas, electric trains, and Barbie dolls. However, the most intriguing discovery, found in one of the rooms, was a box containing twelve photo albums, all bearing the same title: “My TV Girls.” These albums contained 911 meticulously organized Polaroid prints, each dated, numbered, and captioned by the author.

A self-portrait annotated by Wilkins serves as the signature of the work. This self-portrait is the key to unraveling the mystery shrouding this body of work and any attempt to solve the “Tom Wilkins enigma.”

—Sébastien Girard

p. 13 Untitled, 2000

Black and white analog photograph printed on baryta paper

4 × 3 1 8 in. (10 × 8 cm)

(TzM 1)

p. 05 Untitled, 1968

Black and white analog photograph printed on baryta paper

31⁄8 × 2 in. (8 × 5 cm)

(TzM 2)

p. 17 Untitled, 2003

Black and white analog photograph printed on baryta paper

51⁄8 × 31⁄2 in. (13 × 9 cm)

(TzM 3)

p. 19 Untitled, 2005

Black and white analog photograph printed on baryta paper

5 1⁄ 2 × 3 1 2 in. (14 × 9 cm)

(TzM 4)

p. 20 Untitled, 1990

Black and white analog photograph printed on baryta paper

2 3 ⁄ 4 × 4 in. (7 × 10 cm)

(TzM 6)

p. 21 Untitled, 1995

Black and white analog photograph printed on baryta paper

3 1⁄ 2 × 4 3 ⁄ 4 in. (9 × 12 cm)

(TzM 5)

p. 23 Untitled, 2003

Black and white analog photograph printed on baryta paper

2 3 ⁄ 8 × 3 1 ⁄ 8 in. (6 × 8 cm)

(TzM 7)

p. 24 Untitled, 2000

Black and white analog photograph printed on baryta paper

4 × 4 3 ⁄ 4 in. (10 × 12 cm) (TzM 8)

p. 25 Untitled, 1993

Black and white analog photograph printed on baryta paper

4 × 5 1⁄ 2 in. (10 × 14 cm) (TzM 9)

p. 27 Untitled, 1986

Black and white analog photograph printed on baryta paper

4 × 2 3 ⁄ 4 in. (10 × 7 cm) (TzM 10)

p. 29 Untitled, 2003

Black and white analog photograph printed on baryta paper

2 3 ⁄ 8 × 3 1 ⁄ 8 in. (6 × 8 cm) (TzM 11)

p. 31 Untitled, 1992

Black and white analog photograph printed on baryta paper

3 1⁄ 2 × 4 3 ⁄ 8 in. (9 × 11 cm)

(TzM 12)

p. 32 Untitled, 2006

Black and white analog photograph printed on baryta paper

3 1⁄ 2 × 5 1 ⁄ 8 in. (9 × 13 cm) (TzM 13)

p. 33 Untitled, 2005

Black and white analog photograph printed on baryta paper

3 5 ⁄ 8 × 5 1 8 in. (9.3 × 13 cm)

(TzM 14)

p. 35 Untitled, 2010

Unique digital color print on Fuji paper

15 × 10 in. (38 × 25.5 cm)

(TzM 15)

p. 37 Untitled, 2009

Unique digital color print on Fuji paper

15 × 11 3 ⁄ 8 in. (38 × 29 cm)

(TzM 16)

p. 38 Untitled, 2009

Unique digital color print on Fuji paper

15 × 11 in. (38 × 28 cm)

(TzM 18)

p. 39 Untitled, 2010

Unique digital color print on Fuji paper

15 × 10 in. (38 × 25.4 cm)

(TzM 17)

p. 41 Untitled, 2009

Unique digital color print on Fuji paper

15 × 11 1 2 in. (38 × 29.3 cm)

(TzM 19)

p. 43 Untitled, 2011

Unique digital color print on Fuji paper

15 × 10 7 ⁄ 8 in. (38 × 27.5 cm)

(TzM 20)

p. 45 Untitled, 2012

Unique digital color print on Fuji paper

15 × 10 5 8 in. (38 × 27 cm)

(TzM 21)

p. 46 Untitled, 2011

Unique digital color print on Fuji paper

15 × 9 1⁄ 2 in. (38 × 24.5 cm) (TzM 22)

p. 47 Untitled, 2012

Unique digital color print on Fuji paper

15 × 10 1 4 in. (38 × 26 cm) (TzM 23)

p. 49 Untitled, 2014

Unique digital color print on Fuji paper

15 × 9 5 ⁄ 8 in. (38 × 24.5 cm) (TzM 24)

p. 51 Untitled, 2016

Unique digital color print on Fuji paper

15 × 10 5 ⁄ 8 in. (38 × 27 cm) (TzM 25)

p. 52 Untitled, 2015

Unique digital color print on Fuji paper

15 × 11 3 ⁄ 4 in. (38 × 30 cm) (TzM 27)

p. 53 Untitled, 2018

Unique digital color print on Fuji paper

15 × 11 3 ⁄ 8 in. (38 × 29 cm) (TzM 26)

p. 61 My TV Girls #02, 1978

Grid of nine SX-70 Polaroids

18 1 ⁄ 8 × 15 3 8 in. (46 × 39 cm) (TWk 1)

p. 63 My TV Girls #11, 1978

Grid of nine SX-70 Polaroids

18 1 ⁄ 8 × 15 3 8 in. (46 × 39 cm) (TWk 2)

p. 65 My TV Girls #034, 1980

Grid of nine SX-70 Polaroids

18 1 ⁄ 8 × 15 3 8 in. (46 × 39 cm) (TWk 3)

p. 67 My TV Girls #035, 1980

Grid of nine SX-70 Polaroids

18 1 ⁄ 8 × 15 3 8 in. (46 × 39 cm) (TWk 4)

p. 69 My TV Girls #037, 1980

Grid of nine SX-70 Polaroids

18 1 ⁄ 8 × 15 3 8 in. (46 × 39 cm) (TWk 5)

p. 71 My TV Girls #059, 1980

Grid of nine SX-70 Polaroids

18 1 ⁄ 8 × 15 3 8 in. (46 × 39 cm) (TWk 6)

p. 73 My TV Girls #064, 1980

Grid of nine SX-70 Polaroids

18 1 ⁄ 8 × 15 3 8 in. (46 × 39 cm) (TWk 7)

p. 75 My TV Girls #074, 1981

Grid of nine SX-70 Polaroids

18 1 ⁄ 8 × 15 3 8 in. (46 × 39 cm) (TWk 8)

p. 77 My TV Girls #077, 1981

Grid of nine SX-70 Polaroids

18 1 8 × 15 3 8 in. (46 × 39 cm) (TWk 9)

p. 79 My TV Girls #078, 1981

Grid of nine SX-70 Polaroids

18 1 8 × 15 3 8 in. (46 × 39 cm) (TWk 10)

p. 81 My TV Girls #090, 1981

Grid of nine SX-70 Polaroids

18 1 8 × 15 3 8 in. (46 × 39 cm) (TWk 11)

p. 83 My TV Girls #099, 1981

Grid of nine SX-70 Polaroids

18 1 8 × 15 3 8 in. (46 × 39 cm) (TWk 12)

Published in conjunction with the exhibition Tomasz Machciński and Tom Wilkins, presented by Ricco/Maresca Gallery (New York) in partnership with christian berst art brut (Paris) and The Tomasz Machciński Foundation (Warsaw) at the Independent Art Fair: May 9–12, 2024.

Published by Ricco/Maresca Gallery

529 West 20th Street | 3rd Floor New York, NY 10011 riccomaresca.com

Copyright © 2024 Ricco/Maresca Gallery

Artworks by Tomasz Machciński © christian berst art brut / Tomasz Machciński Foundation

Artworks by Tom Wilkins © christian berst art brut / Sébastien Girard

“Walk on the Wild Side: Polish Queer Culture, Failure, and Camp in Tomasz Machciński’s Work”

copyright © 2024 Agata Pyzik

“Tom Wilkins: My TV Girls ” copyright © 2024 Christian Berst and Sébastien Girard

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publishers, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Project manager: Alejandra Russi

Editor and designer: Laura Lindgren

Typeset in Optima Nova

Front cover: Tomasz Machciński , Untitled, 2003 (TzM 3) and Tom Wilkins, detail, My TV Girls #02, 1978 (TWk 1)

page 4: Tomasz Machciński, Untitled, 2000 (TzM 28)

page 56 Tom Wilkins, detail, My TV Girls #099, 1981 (TWk 12)

page 58: Tom Wilkins, Me Wearing 38B Beige Playtex Beautiful Ones Lace Bra, 1981. SX-70 Polaroid, 41/4 × 31/2 in. (10.8 × 8.8 cm) (TWk 13)