11 minute read

XV. Design Thinkers in the Kindergarten Classroom

Design Thinkers in the Kindergarten Classroom

VAS POURNARAS

Design thinking “is important in education because we want our students to develop higher-order thinking skills and be able to analyze, synthesize, innovate, and thus readily deal with real-world problems.” 1

In 2019-2020, our kindergarten students embarked on an in-depth study of home and homelessness. But we got to this by an interesting path.

After reading “Fly Away Home” by Eve Bunting, we decided to focus our social studies curriculum on studying birds. Our research about birds led us down many paths including scientifically drawing birds through the process of peer critique and multiple drafts, creating 3-dimensional models of birds, learning about birds through science class, and writing creative stories about birds.

Arguably one of the most rewarding ways we learned about birds was when our class used design thinking as a way to create homes for birds. In small groups, students went through the design thinking process of empathize, define, ideate, prototype, and implement. Design thinking connects to several important academic and social emotional skills that children learn and hone in on in kindergarten, including empathy, curiosity and collaboration. 2 I also believe that for our youngest learners, design thinking gives them a hands-on experience using the information they have been learning about it in class.

As we were learning about birds, final construction of our new elementary school building and playground was taking place. We learned that as part of this, there would be a few trees that would have to be cut down on campus. This brought on many conversations about what we could do to help the birds that lived in those trees who would then become homeless.

Our students have a natural sense of empathy, which can be a powerful motivating force. This empathy was the jumping off point for our design thinking

exploration to create houses for birds. In the design thinking process, empathy is a starting point and centerpiece, and is vital throughout the process. 3

• What birds may have lived in those trees? • What do those birds like for a home? • What would attract the birds back to the area?

These were some of the initial questions our students asked. These initial discussions also helped provide an authentic need to design birdhouses. It is important to have authentic and intriguing needs, opportunities that really resonate with the students when they undergo a design thinking project as this helps build motivation and leads them to dig deep to find creative solutions. Because there is an emotional connection to the task in front of them, students are more willing to be and stay engaged in the face of challenge.

Before we went further, though, we had to decide which birds we would design for. After researching various local birds, our class chose to design for cardinals, blue jays, purple martins, and white-breasted nuthatches. At this point we formed four groups and each group would design for a different bird.

The first step of our design thinking process was empathize, which included learning about the bird for which they would be designing. Our research included a field trip to the Audubon Naturalist Society, a visit from bird expert Ms. K (a student’s grandmother), and both online and book research in the classroom based on questions developed by the students. Building robust background knowledge is an important early step in any projectbased learning, so it is important to build this in before students begin working more independently on their own projects.

Next was the define step, in which children defined the needs of their birds based on their research. Students had been exploring lots of different ideas by this point, so providing them with a structured define step really helped them focus their thoughts. The definitions our students came up with were:

Cardinal: We should make a shelf 8 by 8 inches with three walls and decorate it black with moss and twigs.

Purple Martin: We need to make a bird home that is a white apartment. Each apartment is 7.5 by 7 inches. Each apartment hole is two inches in diameter. We need six apartments. Each apartment needs a porch. The birdhouse should be up high.

White-Breasted Nuthatch: We should make a rectangle birdhouse 12.5 inches high by 6 inches wide by 8.5 inches deep. The hole should be 1.25 inches. It can be yellow, brown, or green and decorated with wood chips or leaves.

Blue Jay: Blue Jays need a platform 8 inches by 8 inches with a pointy roof and 3 walls. It should be decorated with moss and wood. They do not need a hole. visualize their ideas, which helped them develop their thinking.

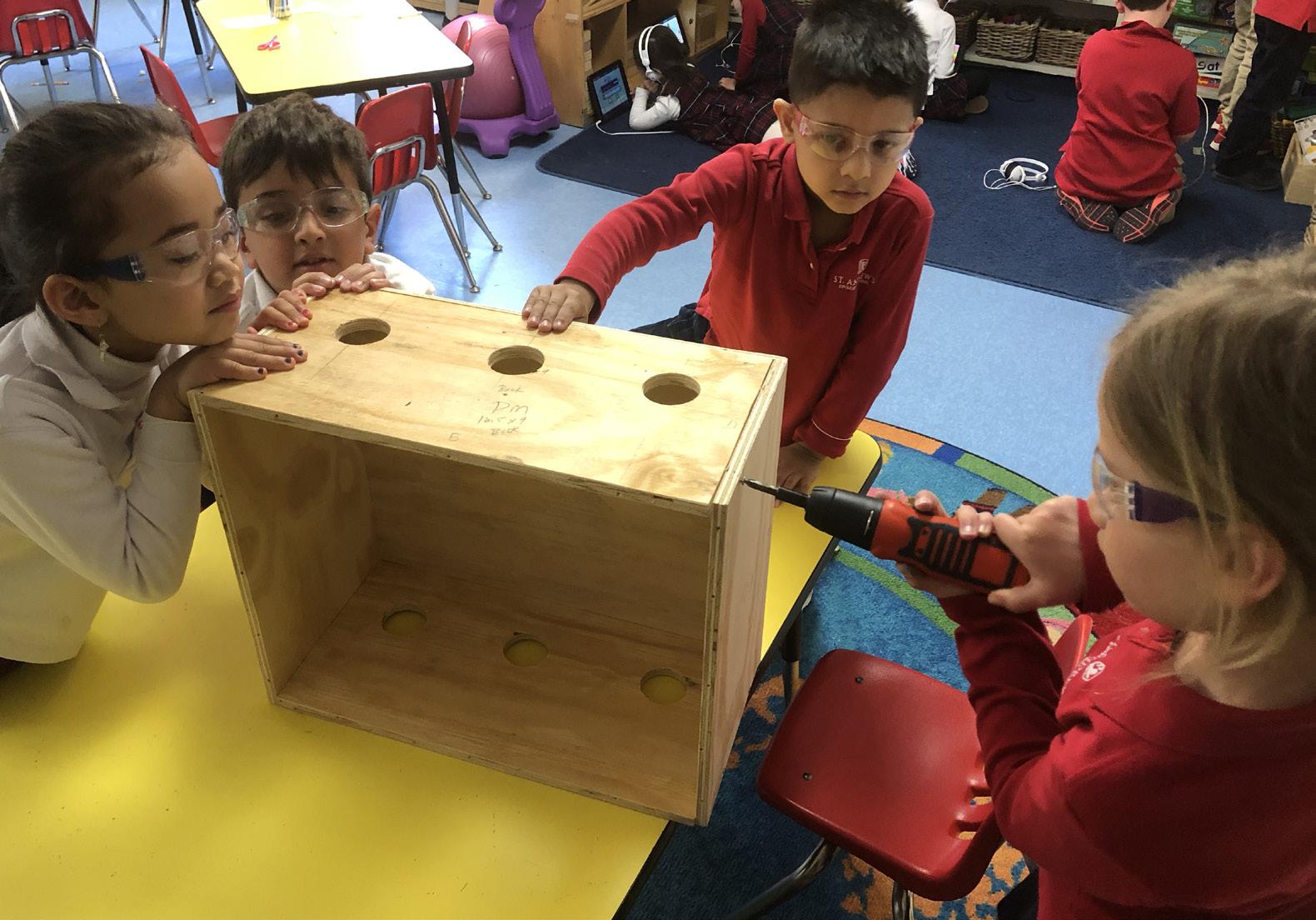

After analyzing these prototypes and figuring out adjustments that needed to be made, students made a second prototype out of cardboard. This prototype was then used as a true model of the actual birdhouses that were built. This final step in our process was what we called implement. Here the students’ prototypes were transferred into wood. After all of the wood was cut for the birdhouses, students used a variety of tools to assemble the birdhouses.

In the third step of our process, ideate, children brainstormed many different ideas and ways to solve the problem based on their definitions and research. It was important during this step that every idea held equal value and no idea was bad or pushed away. Because the students had just created focused definitions in the previous step, they were better able to ideate because they had some concrete constraints to work with. These concrete constraints often served as jumping off points for their creativity.

After ideate came the prototype step, during which children worked collaboratively to construct prototypes of birdhouses from recycled materials. For our project there were two different rounds of prototypes created. The initial prototype was made out of cardstock, paper, and recycled plastic materials. This allowed for quick prototyping — students could

Throughout the design thinking process kindergarten students had full ownership of their work. The students felt that their designs, even though they look like typical birdhouses, were completely their own. During the process and beyond, students collaborated, showed empathy, and continued to ask questions about birds and talk about the needs of birds even after the project was completed. I believe that using design thinking with some of our youngest students proves to be successful and valuable, and, in addition to building a great and authentic curiosity about a topic, helps them develop some very important social-emotional skills.

Vas Pournaras (vpournaras@saes.org; @ pournava) teaches Kindergarten at St. Andrew’s.

On Pilgrimage in the Classroom

AMY SAPENOFF

Teaching is like a pilgrimage – each term has its own destination and travel companions in students and colleagues. In the summer of 2018, my colleague Chantal Cassan-Moudoud and I were presented with the opportunity to complete an actual pilgrimage through St. Andrew’s Summer Grants Program. Our journey was to Santiago de Compostela, located in the northeast corner of Spain.

The Camino de Santiago, or the Way of St. James, began in the Middle Ages. Tradition tells us that the Apostle James was sent to evangelize the Iberian Peninsula and was later buried in Compostela after being martyred in the Holy Land. Eventually, a cathedral was built over his tomb, becoming a holy site for pilgrims.

Today, the Camino is still travelled by thousands of pilgrims each year. While most people no longer walk with religious intentions, the miles convey a deep sense of community and shared life among all those walking. It is common to strike up conversations with those that you meet, to share a coffee after the early morning hours departures, or to chat throughout the evenings in the pilgrims’ hostels.

Our two-month expedition consisted of waking up at 5 a.m. and walking somewhere between 15-25 miles. From our starting point in Cahors, France, Chantal and I would walk a total of 700 miles. As the path continued to lead us east, it became a time of tremendous introspection and prayer for me, the kind of thinking that can only be sustained in silence and with the simplicity of one who carries all their possessions on their back. Many of the judgments I arrived at over the course of that summer not only answered my personal questions, but also revealed a new path to follow in my teaching.

The experience of the Camino was one of grit, first in the most obvious sense, as something that begged for tenacity and determination to complete. However, it also became an experience of grit as conceived of in the research of Angela Duckworth, a psychologist and professor at the University of Pennsylvania and author

of the book “Grit: the Power of Passion and Perseverance.” On her website, she defines grit as “the tendency to sustain interest and effort toward very long-term goals.” 1 In the second part of her book, Duckworth describes ways in which to cultivate “grit from the inside out” including two key elements: interest and purpose.

Interest, as Duckworth draws out, is an essential part of grit. It is hard to persevere when one is apathetic about the task at hand. However, she also explains that interest is not simply created in an individual, “through introspection. Instead, interests are triggered by interactions with the outside world. The process of interest discovery can by messy, serendipitous, and inefficient. This is because you can’t really predict with certainty what will capture your attention and what won’t.” 2 Interest in something is not invented but revealed, often as one explores.

My desire to keep on walking (rather than taking a bus or taxi) was not only about reaching Santiago, my known and stated goal. My desire was also linked to an openness to reality that was being generated in me. The miles that were most significant were not the miles that I walked the fastest or most effectively used my walking poles. The miles became precious when I was attentive and open to receive whatever came my way, when I allowed myself to be surprised and captivated by a beautiful view or the joy of an unexpected walking companion. The miles that carried the

most meaning were precisely those that could not be reduced to my own effort.

This is a conviction that I have tried to share with my students. Teaching always implies negotiating with disinterested students who are confident that they could never be struck by studying the French Revolution or westward expansion. It requires a shift in mindset to move through the school year with the conviction that each class period offers the possibility to discover something new. The joy of discovery provides a catalyst for renewed vigor in inquiry, thinking, and reflection and introduces curiosity and wonder as essential pedagogical starting points.

The second key element in cultivating grit is purpose. Duckworth explains that “human beings have evolved to seek meaning and purpose,” 3 describing how “gritty people see their ultimate aims as deeply connected to the world beyond themselves.” 4 One is motivated to work hard when they see a job or responsibility elevated to a calling in life. This importance of purpose and relevance as a driving force is a common theme in theories of motivation, such as self determination theory 5 and expectancy value theory. 6

My Camino was not merely a hike across Europe. Rather, my walking coincided with knowing that my intentions and questions were being taken up by the great history of many hundreds of thousands of pilgrims who had walked this same path throughout the centuries, ultimately to be entrusted to St. James in Santiago de Compostela to bring to the Lord. This sense of belonging to a community greater than myself was a valuable companion on my journey. Grit does not mean that you have all the competencies from the beginning but that you are willing to fail and grow in pursuance of a goal. To be converted. Grit is interwoven with a growth mindset and a sense of belonging and purpose.

It is for this reason that I do not shy away from introducing ultimate ends into my teaching practice. My students often complete journal activities that ask them to ponder the nature of justice and freedom by considering how these ideals have been either exalted or manipulated in different eras. Much of history can be viewed through the lens of a dialectic or a will to power, but is this what the heart longs for? Students are willing to work hard — hard enough that it begs for tenacity and determination, for grit, to complete — to seek the answer to a question that helps them to make sense of their own life and desire.

Arriving in Santiago and completing the Camino illuminated a paradox of grit. Grit is more than buckling down and trying harder. It also implies responding to what is given and allowing oneself to be changed as you move towards a greater horizon. And now, that’s a journey I am taking with my students every year.