RISD

RISD News

Shahzia Sikander MFA 95 PT/PR is at the NY Supreme Court, Arts and Letters, RISD says “no” to rankings, Class in India, Big Tree, 1900 to Now, Please Touch and Global Security

Anna Weyant 17 PT and Urvi Sharma 17 FD named to Forbes 30 Under 30

Tim Finn 00 FAV on collecting comics

Class Notes

On the Street: Sculpture by Fitzhugh Karol MFA 07 CR

Encyclopedia of Invisibility

From outer space to the Mississippi Delta, Tavares Strachan 03 GL creates work that “exemplifies the power of human ingenuity.”

The Melt Acacia Johnson 14 PH photographs the warming Arctic.

Destination City

With the Sixth Street Bridge and Destination Crenshaw, Michael Maltzan BArch 85/P 24 and Gabrielle Bullock BArch 84—friends and former RISD classmates—are reimagining the concept of community in Los Angeles.

Radical Generosity

Lina Sergie Attar MArch 01 finds shelter for those displaced by the massive earthquake that rocked parts of Turkey and Syria.

Michael

The Sixth Street Bridge has become a destination spot, and in this case, a backdrop for a photo shoot. Photo by Páll Stefánsson.

Maltzan and Gabrielle Bullock on The Sixth Street Bridge in LA. The bridge was designed by Michael Maltzan Architecture. Photo by Páll Stefánsson.

Maltzan and Gabrielle Bullock on The Sixth Street Bridge in LA. The bridge was designed by Michael Maltzan Architecture. Photo by Páll Stefánsson.

This year, I’ve spent a great deal of time learning about RISD’s rich and storied history and admiring the legacy and impact of our more than 31,000 alumni who make significant contributions not only in art and design fields but also across industry, impacting everything from business and technology to environmental sustainability. Reflecting on this past academic year reveals many reasons to celebrate and lessons to grow from, but after a whirlwind first year, I admit to looking forward to the summer.

Summer often marks a moment when our pace slows, which allows for more contemplation, synthesis, and rejuvenation. Summer allows us to reconnect with one another as we enjoy warmer temperatures, additional daylight hours, and the natural beauty around us. Whether relaxing around fire pits, going on hikes, sitting at the beach, or traveling with our beloveds, summer almost always represents reconnection with more of what we hold dear in life.

In 2022, the alumni survey revealed that you missed the connection a physical magazine focused on your news, updates, and events provides. Many of you shared how important a magazine is to helping you be in community with RISD’s vast global alumni network. Thank you for adding your voice to the conversation. On page 60, you can learn more details about the survey results, how we got here, and where we’re going.

I am pleased to present to you an alumni publication— reimagined.

The magazine will explore how art and design informs our experience of the world by sharing stories from the RISD community that focus on themes that matter to you. You’ll read about art and design education not only at RISD but also in terms of its value in the larger world. And you’ll read about how RISD alumni are effecting societal change in critical areas such as sustainability, equity and social justice, and emerging technologies like AI.

For this inaugural issue, we’ve gathered stories that showcase alumni whose work strengthens their local communities and brings people together. Read on to learn about friends and former classmates

Michael Maltzan BArch 85/P 24 and Garbrielle Bullock BArch 84, whose work focuses on uniting people through design that encourages interaction. Enjoy a profile on Tavares Strachan 03 GL, a 2022 MacArthur Foundation “Genius Grant” fellow, and view a photo essay by Acacia Johnson 14 PH documenting the warming Arctic. Finally, a feature story on Lina Sergie Attar MArch 01 shares how she traveled to Turkey to help with disaster relief after the devastating earthquakes that struck both Turkey and Syria last February.

I hope you enjoy the new alumni magazine, and I look forward to hearing what you think. May this issue’s profiles, updates, features, and stories encourage you to deepen your connection to RISD and each other.

—Crystal Williams, RISD PresidentHavah...to breathe, air, life, an exhibition by Shahzia Sikander MFA 95 PT/PR, a MacArthur Award–winning artist, comprises two golden sculptures, NOW (pictured above) and Witness, located at nearby Madison Square Park, both of which focus on justice.

“Havah” means “air” or “atmosphere” in Urdu, and “Eve” in Arabic, Hebrew and other languages.

“The recent focus on reproductive rights in the U.S., after the Supreme Court overturned the landmark 1973 decision that guaranteed the constitutional right to abortion in the U.S., comes to the forefront,” Sikander said in an artist’s statement.

“In the process, it is the dismissal, too, of the indefatigable spirit of the women, who have been

collectively fighting for their right to their own bodies over generations. However, the enduring power lies with the people who step into and remain in the fight for equality. That spirit and grit is what I want to capture in both the sculptures.”

The exhibition was co-commissioned by Madison Square Park Conservancy and Public Art of the University of Houston System (Public Art UHS). This commission, Sikander's first major outdoor work, expands her practice into civic space. The exhibition was on view in New York through June 4, 2023, and has since left for Houston, where it can be viewed at the Cullen Family Plaza, at the University of Houston.

RISD says no to rankings.

RISD will no longer participate in U.S. News & World Report’s annual “best college” school rankings, citing the inability of rankings to accurately assess art and design education while also running counter to principles of social equity and inclusion.

“Principally, Rhode Island School of Design does not measure the value of our students or our academic programs based on the same factors used by U.S. News & World Report,” RISD President Crystal Williams wrote in a communication to the campus community.

“Our educational model is predicated on three primary ways of learning: visual, material and intellectual. The value of our unique form of education can be seen and felt in the daily impact our students, alums, faculty and staff have on the world.”

Until last year, U.S. News & World Report categorized RISD and other art and design schools as “Specialty Schools: Art.” Under this heading, RISD’s

RISD alumni join Academy of Arts and Letters.

Arlene Shechet MFA 78 CR, Huma Bhabha 85 PR and Michael Maltzan BArch 85 were among nineteen new members and four honorary members inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters during its annual ceremony, which was held on May 24, 2023.

The Ukrainian writer Andrey Kurkov, inducted into Foreign Honorary membership, delivered the keynote.

Shechet, Bhabha and Maltzan were joined by such luminaries as writer Phillip Lopate, director Francis Ford Coppola and actress Frances McDormand; Coppola and McDormand became honorary members.

The American Academy of Arts and Letters was founded in 1898 as an honor society of the country’s leading architects, artists, composers and writers. Early members included William Merritt Chase, Childe Hassam, Julia Ward Howe, Henry James, Edward MacDowell, Theodore Roosevelt, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, John Singer Sargent, Mark Twain and Edith Wharton. The Academy’s 300 members

undergraduate programs (reflecting 80 percent of matriculants) were unranked. However, because of small curriculum changes to some of RISD’s programs, last year the school was categorized as a “regional school.”

“As is often the case, change triggers important reflection and opportunities to reassess and revise a course of action,” added President Williams.

“So, while we ranked third out of 181 schools in the ‘Best Regional Universities North,’ a category placing us in comparison to institutions with which we share very little in common, this change by U.S. News catalyzed our deeper thinking about the ranking system overall, its relevance to RISD and our work as educators, and the criteria used to create it. Many of those criteria have been written about in critical terms and publicly questioned, and are unambiguously biased in favor of wealth, privilege and opportunities that are inequitably distributed.”

are elected for life and pay no dues, according to the Academy’s website.

The Academy’s American Honorary membership, which began in 1983, recognizes up to twenty Americans of extraordinary artistic achievement whose work falls outside or transcends the fields of architecture, art, literature and music composition. Foreign Honorary membership, which was established in 1929, celebrates up to seventy-five distinguished architects, artists, writers and composers from other countries whose work the Academy’s membership greatly admires.

In addition to electing new members as vacancies occur, the Academy’s website indicates that it seeks to foster and sustain an interest in literature, music, and the fine arts by administering over 70 awards and prizes totaling more than $1 million, exhibiting art and manuscripts, funding performances of musical theater, purchasing artwork for donation to museums across the country and presenting talks and concerts.

Students push the boundaries of journalism.

Students in a spring Computation, Technology and Culture studio created work with the potential to transcend traditional gallery settings and reach wide audiences through print journalism and other news outlets. The course, Artists on the News, was developed last spring by journalist Marisa Mazria Katz, known for her writing about the arts in the Middle East and North Africa as the founding editor of Creative Time Reports and the founding editorial director of the Eyebeam Center for the Future of Journalism.

“I see artists as distinctively adept at encouraging all of us to be more engaged,” said Mazria Katz, “no matter if they are tackling issues like climate degradation, technology, surveillance or politically motivated violence.”

Graphic Design major Alina Spatz 23 GD, who took the course last year as her home country of Russia invaded Ukraine, described it as “life-changing. I’d been interested in politics and activism since high school,” she said, “but I didn’t understand how design could fit in. Marisa opened my eyes to the ways that artists and designers can participate in those worlds.”

Mazria Katz brought in professional artists, journalists and editors nearly every week to explain how they use unconventional forms of expression to tell real-world stories. Students enrolled in the course received firsthand insights from such experts as journalist and Knight Wallace fellow Mary Cuddehe, curator Jake Charles Rees from the Centre for Investigative Journalism and Atlantic editor Matt Seaton.

After wrapping up her time at Eyebeam, Mazria Katz and Rees co-launched the Center for Artistic Inquiry and Reporting, a nonprofit producing artistled investigations that push the boundaries of traditional journalism. “I act as a kind of connector,” she said, “helping artists imagine the stories they want to tell, but also finding the right outlets for their work.”

She has generously helped RISD students pitch projects they are creating for her class to prominent publications. For example, Spatz’s personally motivated piece about Putin’s war on independent media was published in The Nation last September.

Brian Selznick’s new book is a “great joy.”

Big Tree, an illustrated novel by Brian Selznick 88 IL, was published by Scholastic on April 4, 2023.

According to The Hollywood Reporter, Big Tree began as an original idea from Steven Spielberg with Illumination Entertainment founder and CEO Chris Meledandri. Meledandri’s animation studio will own the film rights for the book.

Big Tree follows two sycamore seeds, Louise and Merwin, “who hope to one day set down roots and become big trees. But when a fire forces them to leave their mama tree prematurely, they find themselves catapulted into the unknown, far from home,” according to Selznick’s website.

“Creating Big Tree was a great joy and an even greater challenge because I was telling a story about nature from nature’s point of view,” Selznick said in a statement to Entertainment Weekly. “It grew into a narrative I’m very proud of, one that reminds us to stop and listen to the world around us, and to help those who need to be helped. These themes seem to grow more and more urgent with each passing day.”

Spielberg told The Hollywood Reporter that “the tale of the natural world is the greatest story we have to tell, and Brian delivers a brilliant chapter of it in the pages of Big Tree. It was an absolute joy for Chris and me to help grow the seed of this idea and then sit back and watch Brian’s singular talent produce such a wonderful book.”

Selznick is the best-selling author of The Invention of Hugo Cabret (winner of the Caldecott Medal), which inspired Martin Scorsese’s Oscar-winning Hugo. His novel in short stories Kaleidoscope was called a “lockdown masterpiece” by The New York Times

He’s also the author and illustrator of Wonderstruck, which was made into a movie by Todd Haynes, with the screenplay written by Selznick.

Selznick, RISD’s 2021 Helena Adelia Rowe Metcalf Visionary Award winner, spoke at RISD and signed copies of Big Tree in May. He sat down with RISD Magazine for a Q&A, which will be published in the October issue.

A global studies course in Jaipur, India.

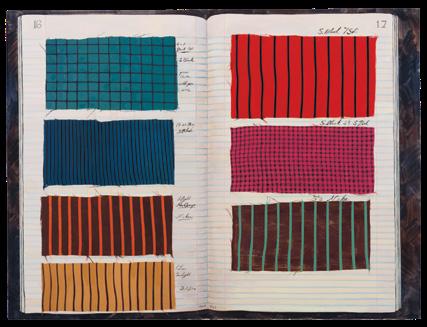

Words by Simone SolondzStudents taking a wintersession global studies course in India collaborated with artisans in Jaipur using handcrafting techniques that have been perfected over hundreds of years.

“Handcraft and gracious hospitality are both embedded in the ethos of the Indian way of life,” said textiles faculty member Joy Ko. “Students at RISD are trained to be designer, artist and maker but had to first learn how to communicate with their hosts and be good guests before collaborating with the highly skilled, multigenerational artisans they met.”

Ko and apparel design professor Catherine Andreozzi 87 AP developed and both led the course, India_Sensed, whose name became a kind of touchstone for students as their journey unfolded.

“Collaborating with people who don’t speak your language changes the way that you would normally work,” Andreozzi said. “You have to rely on other modes of expression, such as drawing and translation apps that result in laughter and dancing.”

Students worked with master Dabu mud printer Padamshree R K Derawala, jewelry designer Neelum

Narang, embroidery master Jayshree Kumavat and Badshah Mian, an expert in Lehariya resist dyeing. Access to these artisans was made possible through a partnership with Sheela Lunkad, Rajeev Lunkad and Sonal Chitranshi of New Delhi–based creative design organization DirectCreate.

Yue Zi 23 AP zeroed in on jewelry making for her final project. “My thesis revolves around my fascination with bones and skeletal forms,” Yue said. “Inspired by jewelry we saw in the Amrapali Museum, I worked with Neelum and the artisans in her studio to create delicate silver pieces to adorn the hand and highlight its skeletal structure.”

Benjamin Garbus 25 ID was particularly drawn to the patterns and structures of the historical sites the class visited on the road to Jaipur.

“The way that nature exists in combination with architecture reminded me of nature’s role in craft,” he said. “An ant crawling across drying fabric is a part of the making process, just as a monkey crawling on a roof is a part of the building. The unpredictable interaction is what makes the final product unique.”

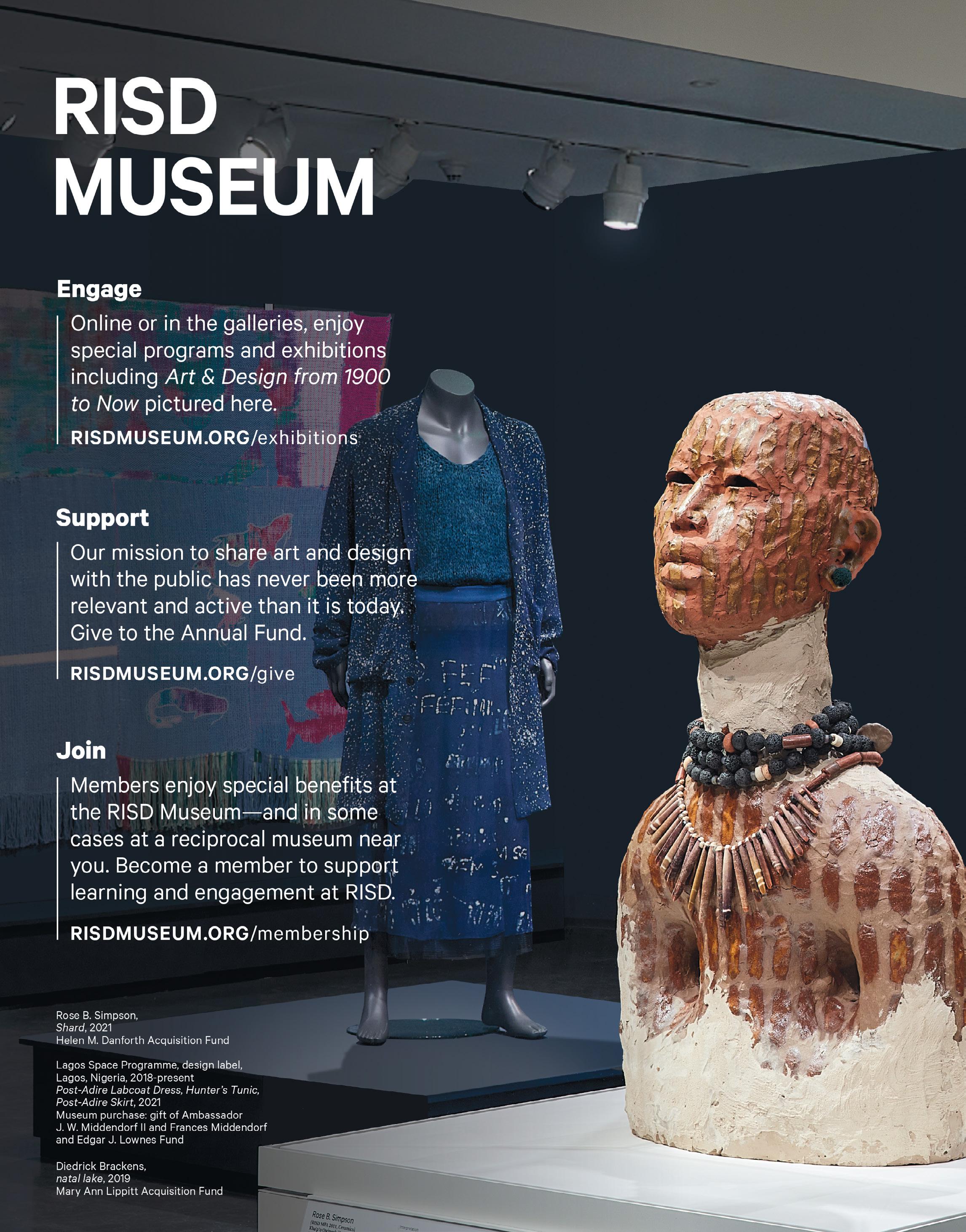

RISD Museum exhibition focuses on belonging.

Words by Kira GoldenbergWhile brainstorming the RISD Museum exhibition that became Art and Design from 1900 to Now—on view until June 9, 2024—the curators wanted to decide, collectively, the through line of the show.

“We all got together to talk about what we thought would be a way to engage all our different collections within a single show,” said Dominic Molon, interim curator of RISD Museum.

The group settled on a theme of belonging. In the spirit of the theme, the development of 1900 to Now was vastly different from the museum world’s standard curator-led, decision-making process because museum staff decided to work with artists and community members to shape the vision of the show.

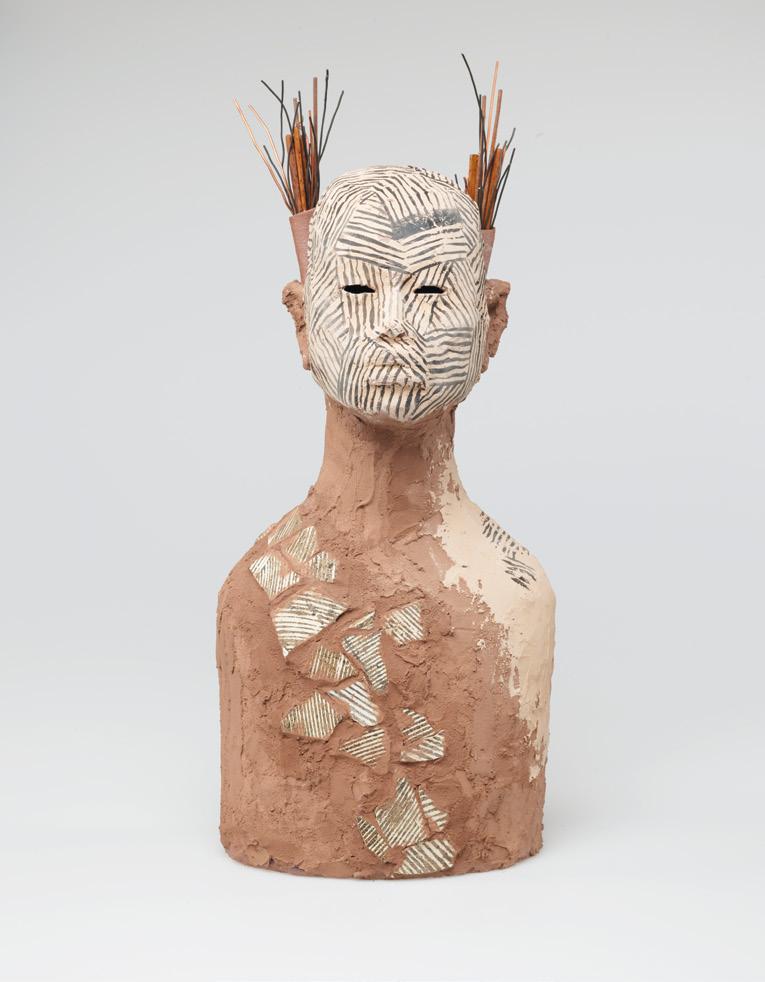

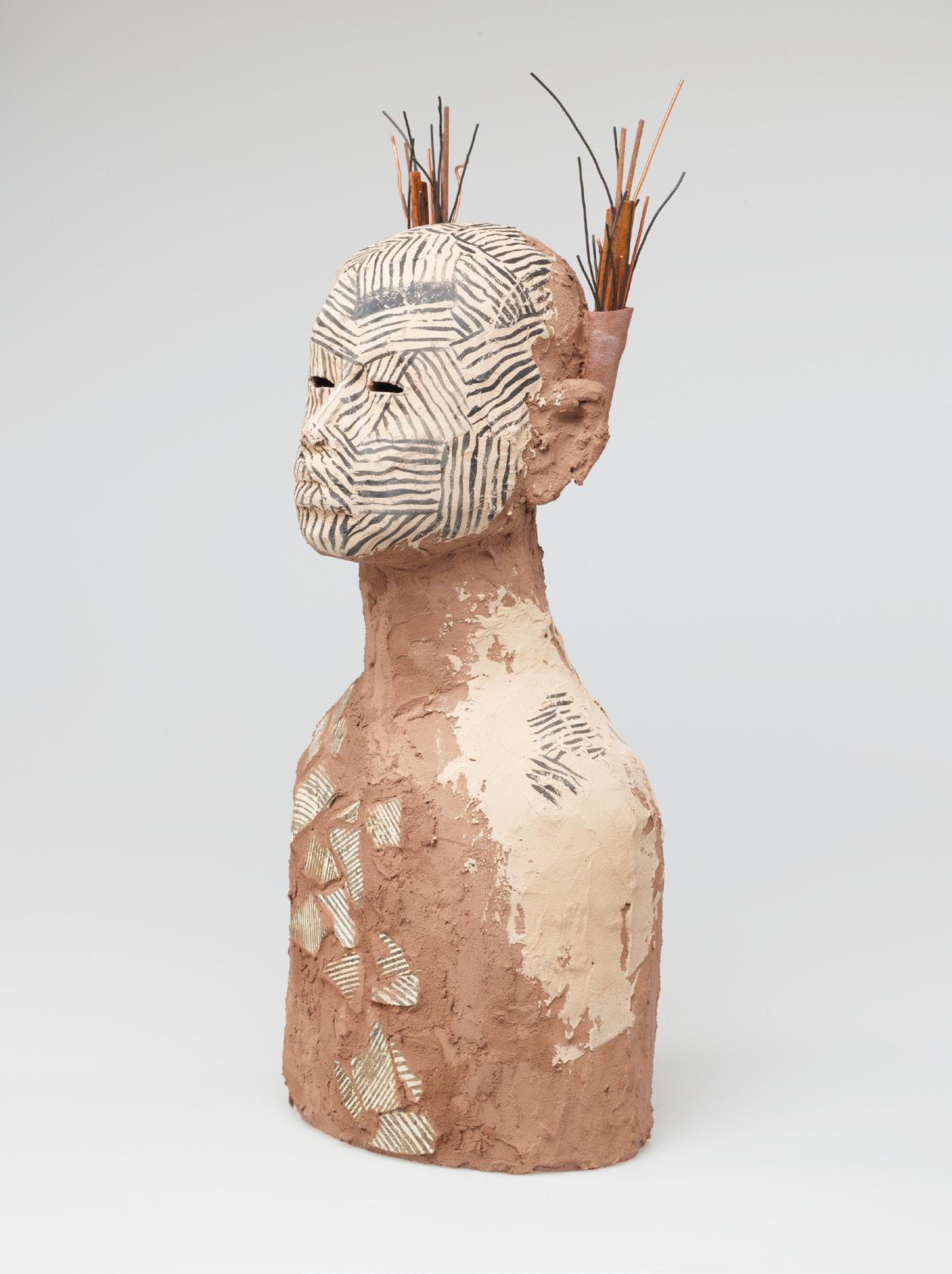

This show was developed over the past two years through partnerships between staff, students, teachers and several of the artists whose works are on view. These community members included the RISD Art Circle Teens, a group of high school artists and art enthusiasts; Rhode Island K-12 teachers; and four RISD alumni artists, Nathaniel Oliver 18 PT, Rose B.

Simpson

“Drawing together works on paper, costume and textiles, painting, sculpture, photography, and decorative arts and design, the installation reflects the interconnectedness of the disciplines RISD teaches and the cross pollination among art forms and media that can influence how artists work,” Molon said.

The exhibition contains pieces in multiple media from seventeen countries and features a commitment to centering on the work of artists from the LGBTQ and Black Indigenous and People of Color communities as well as women artists. These works are spread out across more than 9,000 square feet and make uniquely profound statements about the museum’s permanent collection by virtue of the outside eyes involved in developing innovative relationships between them.

Molon was excited that Oliver and Simpson agreed to collaborate with him on Facts and Figures, the portion of the exhibition he curated. During their

conversation, Simpson, who has two works on view in the current exhibit, raised the idea of making transparent the amount and provenance of funds used to purchase the works on display.

She remembered, as a student, being shocked at a major purchase the museum made because the money it took to buy it could have been used instead to support a number of early-career artists from underrepresented communities.

“That was the first time it really came to hit me— value is interesting and art objects are a reflection of value,” Simpson said. “That makes the museum more of a valuable place or a more influential museum because they own that [piece] rather than fifty pieces by people who could benefit from representation.”

Molon said that decisions made within the art world—what to purchase, what to exhibit, what not to display—are hidden, “opaque whether intentional or not.”

For Simpson, spurring critical thought around the value of art and representation is one part of the 1900 to NOW exhibit.

“It was interesting to be in that situation where you are a part of that value judgment,” she said. “And then you ask yourself, ‘What’s feeding my value judgment? Where do my values come from? Who built the structure of my values and how is that influenced by Western culture, by colonization?’”

1900 to Now was made possible by grants from the Terra Foundation for American Art and the Rhode Island State Council on the Arts, with support from individual donors.

RISD Museum is supported by a grant from the Rhode Island State Council on the Arts, through an appropriation by the Rhode Island General Assembly. It’s also supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, and with the generous partnership of the Rhode Island School of Design, its Board of Trustees, and Museum Governors.

New exhibitions include The Performative Self-Portrait It explores photography as a vehicle to consider ways artists use self-portraiture to enact the self, question history and articulate identity.”

For more information about the museum, visit: risdmuseum.org.

Feel free to climb into the art.

Do not touch the art. On second thought, sophomores in Matt King’s fall sculpture class wanted museum goers to touch and, in some cases, climb into their work.

“We began by visiting the RISD Museum and discussing the taboo around touching objects in art settings and the various ways that artists have skirted it,” said King, critic—sculpture faculty member. “We set aside the no-touch norms of most galleries and museums and made work that invited viewers to physically engage with it,” King said.

At a mid-semester crit, the students presented sculptures intended to be complete only when a human body interacted with them. King said that the work was dynamic and varied, and the students were generous and honest in the feedback they gave one another.

Michael Kays 25 SC invited viewers to step up onto a makeshift stool to look inside his untitled mixed-media sculpture. Students observed that from the outside the stool seemed very dangerous, but the inside was really serene. Kays explained the piece is

about addiction, overdose and recovery, and “accepting life on its own terms.”

Director of Public Programming Deborah Clemons welcomed the class into the museum’s Grand Gallery and reflected on the interactive pieces she’s helped curate over the years. “A couple of years ago, artist Pablo Helguera, currently an assistant professor at the College of Performing Arts at the New School, created an installation for the Raid the Icebox Now series that looked like a residence and allowed visitors to sit on the furniture and read the books,” Clemons recalled.

Other interactive installations invited visitors: to meditate (Nathan Wong 19 PR, Intermediary, 2019), make their own prints on site (Locally Made, 2013), and record their voices (Sebastian Ruth, Witnessing, 2019–20).

Clemons advised the students to “Think about how to work around limitations and get to the essence of your piece.” She asked, “How can you avoid confusing visitors by using signals to indicate that it is OK to touch the art?”

exploring themes of

Design to enhance global security.

Words by Tom Kertscher

Words by Tom Kertscher

While the nuclear threat is not top of mind for most Americans, Russia’s war in Ukraine has once again brought the issue back into the spotlight. And it is a strong focus of Tom Weis MID 08, an associate professor in industrial design at RISD and founder and partner of the Altimeter Design Group.

Design can’t directly enhance global security, Weis likes to remind his students, but his work helps people who are on the front lines of that mission do their jobs better.

Weis’s workshops “shift the dialogue between individuals and organizations on nuclear security that can often get stuck in a stagnant, us-versusthem mentality,” said Elizabeth Kistin Keller, an Oxford-trained researcher and an interdisciplinary problem-solver at Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

At Sandia, Weis and the Altimeter Design Group, in collaboration with subject-matter experts within the lab, developed a role-playing exercise to simulate the Texas power-grid failure in 2021. The participants took on roles of leaders in areas such as local

government and infrastructure. Kistin Keller said such exercises “help us continuously improve the ways in which we are able to apply advanced technologies and technical expertise to avoid, mitigate and recover from disruptions to critical infrastructure.”

Weis consults with even larger institutions, including the United Nations and the International Atomic Energy Agency.

“Some of these organizations were born out of the 1950s, and the world is moving much faster than what their systems had been designed to understand or operate within,” Weis said. “So part of our approach is to leverage the creativity and experiences that participants might have but don’t always get to use in the workplace.”

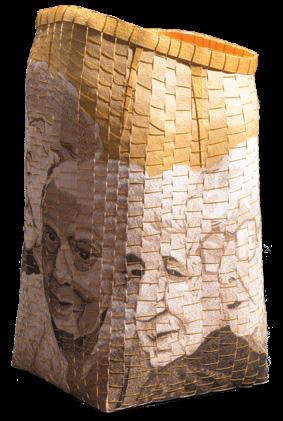

One simple approach can be likened to play: the observation and manipulation of objects.

“Design can activate conversations by bringing ideas to life. Sometimes this takes place through objects, role-playing or facilitated activities. This approach can offer something tangible to respond to that is often insightful in unexpected ways.”

An example is when Weis had his students create a “go bag” filled with things they might need if forced to leave their home on a moment’s notice. Curating these objects personalized what security meant.

“We relate and communicate to the world around us through objects that we purchase, collect, discover or have been gifted. Throughout every stage of our lives, we curate items that signal what we value, cherish or identify with,” Weis said. “These go bags forced students to think about what is truly necessary.”

Weis began to focus on global security after attending a PopTech conference in Camden, Maine, in 2015, when he realized that the nuclear threat had faded from the consciousness of most Americans. PopTech describes itself as “a global network committed to the vanguard of emerging technology, science and creative expression.”

“Speakers did a really great job of using visuals to help communicate both the proximity and the scale of the nuclear threat.” That included the speakers tossing a grapefruit, which stood for how much nuclear material would be needed to destroy a city.

Weis’s collaboration with the United Nations focuses on the arm of the UN that works to prevent and end

Martin Waehlisch, an officer in political and peacebuilding affairs at the UN, said Weis’s work is aimed at sparking new ideas within the massive organization. Design thinking is common in the private sector, but not in the public sector, where solutions often follow past trends rather than looking forward.

Thanks to RISD, “We don’t just say, 'Let’s be creative, let’s be innovative.' We find the method that allows us to have a concentrated and more systematic engagement on change, on design, and on reshaping the means and ways that we use to address international security issues,” Waehlisch said. A video produced by the UN that documents its work with the Altimeter Design Group and RISD shows instructors guiding UN officials in what looks something like play, such as examining pieces of art, manipulating objects and kneading clay; the tasks spur conversation. At one point, the workshop participants handle a miniature Greek pillar and share what it means to them. An Asian woman said it represented an institution; a man said: “I’m Pakistani and I’m Muslim. A Greek pillar doesn’t represent institutions to me.” It was an exercise to break the way people at the UN think—the tasks reminded the participants that people have different cultural biases and frames of reference.

“The aim was not to create world peace; the aim was [to learn] how to spot innovation for change in a very, very complicated organization. It’s a long shot to say that all of this leads to better peace processes. But those kinds of exercises strengthen our ability as an organization,” Waehlisch said.

Weis said the success of his efforts to bring design thinking to organizations focusing on security is measured by the fact that his clients are signing up for more of his services and that students are attracted to RISD courses that use his concepts.

Weis recalled that the IAEA was “the toughest crowd” he had to win over.

“They wanted to have these creative sessions, yet they could not unbolt the tables from the floor; the furniture was designed for a leader-driven process, where there’s someone up front speaking,” Weis recalled. The bolted tables were a metaphor for the groupthink that had cemented itself in the agency.

However, “two years later the IAEA said, ‘We have three rooms for you to completely transform,’” Weis said.

Anna Weyant and Urvi Sharma were included in the 2023 Forbes 30 Under 30 list in the Art & Style category. Fifty-one RISD graduates have been named since the list's launch in 2011

Anna Weyant 17 PT paints luscious portraits and still lifes. The Wall Street Journal referred to Weyant as a “millennial Botticelli.” The women in her paintings deal with circumstances that she characterizes as “low-stakes trauma,” and she creates figures “embroiled in tragicomic narratives.”

Last year, she became the youngest artist represented by the Gagosian Gallery, which hosted her solo show Baby, It Ain’t Over Till It’s Over.

Kira Goldenberg: What turned you into an artist?

Anna Weyant: When Lucian Freud died in 2011, I read about his death in the newspaper. It was my first introduction to his work, and I thought it was magical. Seeing his paintings made me want to paint.

Were you born with a need to create?

Probably. I think that most of us are. It’s in our biology (i.e., reproduction). But, personally, I think that I’ve long been interested in art and design.

How did you find your way to RISD?

I visited RISD while touring colleges with my mom. The campus was beautiful, and the curriculum seemed exciting. I was initially wait-listed and planned to go to another liberal arts college in the area, but RISD ended up working out for me.

What was your favorite part of learning there?

The RISD Museum.

How does your RISD experience influence your current style?

I was fortunate to work with so many wonderful RISD professors. One in particular was Martin Smick, an incredible Providence-based artist and teacher. He taught me about painting materials, techniques, color theory and broader art history. We have kept in touch, and he has continued to offer guidance on these subjects.

What artists inspire you? Which ones influence your own unique style?

I’m looking at historical still life paintings right now—including work by Francisco de Zurbarán and Clara Peeters.

Where can people see your work this coming year?

I will have a painting in a group show taking place at the FLAG Art Foundation in New York City this spring, and I’ll be part of Gagosian’s Art Basel Hong Kong presentation alongside a number of other gallery artists.

Urvi Sharma 17 FD is the cofounder of Providence-based furniture design firm INDO, which uses traditional techniques to create contemporary pieces. Her work has been featured in Architectural Digest and Interior Design, and she has been recognized by Dwell and NYCxDesign

Kira Goldenberg: How did it feel to learn you had been selected to the Forbes 30 Under 30 in the Art & Style category?

Urvi Sharma: It’s funny, because when I was younger, I had put that as a milestone in the future, and it felt very surreal to achieve it. It does feel pretty amazing; I’m not going to lie. But in order to keep working, you have to take these accomplishments but not rely on them for validation. I’m definitely taking it—I know I earned it—but there are more milestones I have to achieve beyond it. It’s telling me that I’m on track, which is encouraging.

How did you become interested in art?

I was always creative and liked to problem solve and invent solutions and things like that when I was a kid. But the thing that made me certain I wanted to do it in a serious way was the pre-college experience at RISD. My mom forced me to do that the summer before my senior year of high school; she was like, “You’re not sitting at home.” I realized there was a whole world outside my own where people were creative. The combination of being independent as a 17-year-old for six weeks and just doing art and hanging out with cool people was the 'aha' moment. I spent my senior year of high school ignoring everything else and trying to get into RISD.

What led you to furniture design?

I didn’t consider furniture as an option at the beginning of my first year. I had been trained to think that industrial design or graphic design was the way to go. But I realized through my time here that furniture was exactly where I wanted to be. I would learn how to make things and make them really well. Furniture design straddled the line between art and design, which I liked. I’m very much a design person, but I didn’t want to do just design. I wanted to be in the middle and have that ability to play, and furniture showed that I could do that.

How did RISD influence your career?

It was probably the community and the relationship with the professors. We were definitely students, but we were given responsibility. All the furniture professors were pretty stellar for me—and the community was definitely a big one. The people I met here are lifelong friends. I met Manan [Narang, her life and artistic partner] through the furniture program as well.

How would you describe your creative process?

I feel like my process, which is very narrative and research based, leads to its own aesthetic. There is a thread that connects all my work for sure, but I don’t think it’s visual, necessarily. I would say that it’s more of an undercurrent. A lot of it is based on personal narrative—so memories, stories, experiences—as well as interaction with crafts and techniques and how to reimagine and recontextualize those techniques in more contemporary settings.

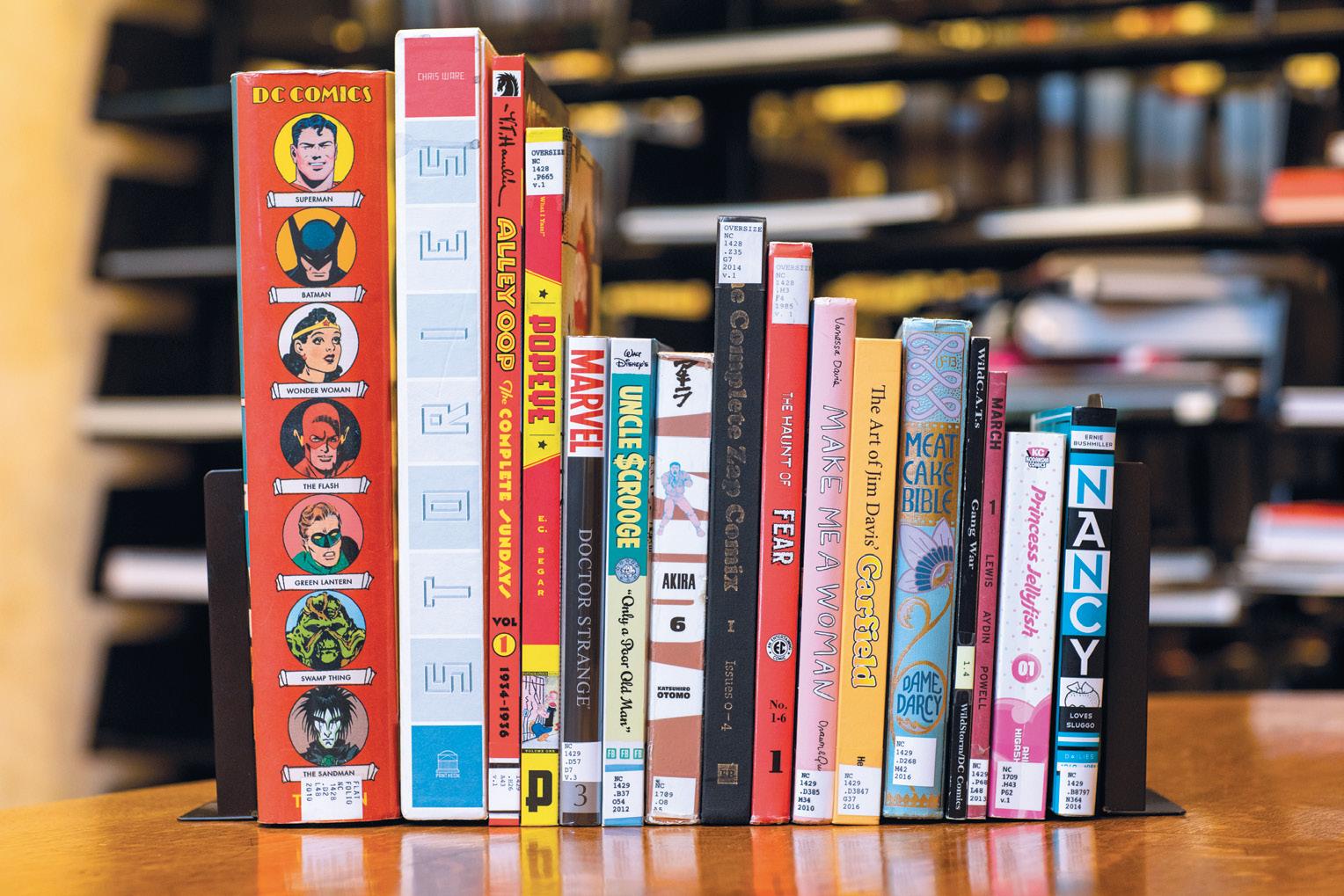

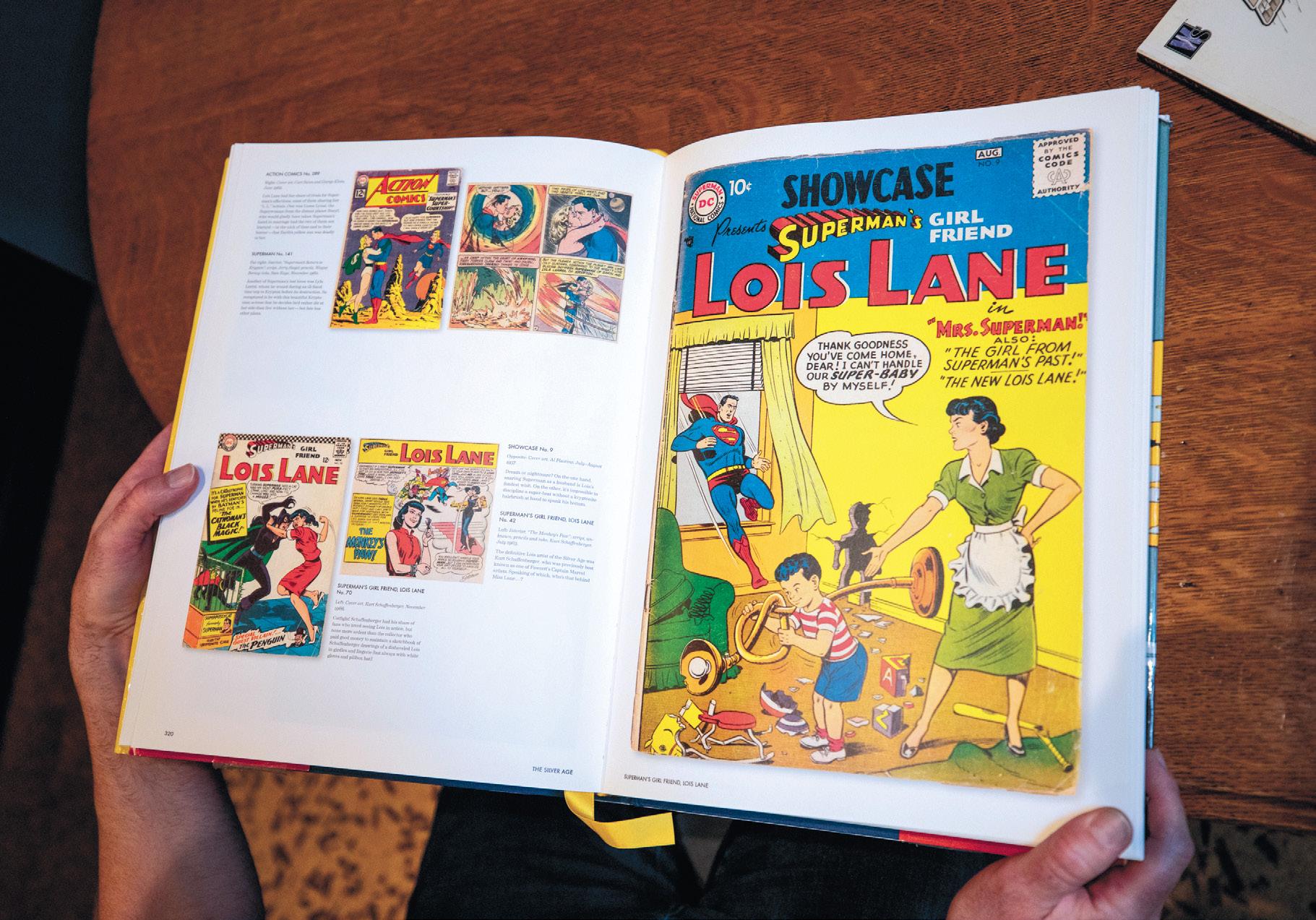

When Tim Finn 00 FAV entered RISD as a student, he was surprised to discover that the RISD Library (now the Fleet Library), in operation since 1878, didn’t have many comics or graphic novels in its collections, which include more than 155,000 volumes and 320 periodical subscriptions (print) in the areas of architecture, art, design and photography.

This was an era, Finn notes, “when you’d go to a bookstore and there’d be Garfield collections and Maus in the humor section because bookstores didn’t know what to do with graphic novels. Maybe Maus was in Judaica or Garfield would be in the kids’ section.

“I don’t think I realistically expected there to be a thousand graphic novels in the RISD library, but I was so dismayed that there were fifteen,” he added. “RISD has an illustration department, and comics are this great American art form,” he remembered thinking.

Finn dates his love of the genre to the childhood experience of watching all available G.I. Joe TV episodes and then discovering more stories available in comic form. He began drawing comics in the fifth grade, and has self-published his own, including

“Comics can be grand and mythic or simple and intensely personal, and hundreds of pages or less than one. They can have detailed and ornate artwork, or stick figures. You don’t need a printing press, a camera, or a computer to make them, just scrap paper and a pencil or pen. I find that range and that accessibility to be wonderful,” Finn said.

Finn decided that the library’s dearth of comics was a situation he could remedy. He asked thenlibrary director Carol Terry if he could donate ten to twenty of the “most important graphic novels,” he said. She agreed and he did, using the pseudonym Rob Muhquay to conceal his generosity from his classmates.

“After I donated those first ten or twenty, I thought I could very quickly double that list, because it’s not really the twenty most important—it’s the forty most important,” he said. So beginning as an undergraduate student and continuing for years afterward, Finn, who has owned Hub Comics in Somerville,

Massachusetts, since 2011, would ship a box to the library every few months, switching to his own name after he graduated. By the library’s own count, he has sent 188 shipments to his alma mater.

“It was nice knowing that they weren’t going to get immediately put in storage or sold at a fundraiser; these really were to build up the collection,” Finn said.

Indeed, Finn’s years of generosity have made comics “a collecting strength in our library,” said Dean of Libraries Margot McIlwain Nishimura.

“We have 421 titles that were gifts of Rob Muhquay and 1,170 from Tim. Altogether, that’s well over one percent of all the library’s holdings,” Nishimura said. (Because the original gifts were processed under the pseudonym, the donor names are still listed separately.) “In terms of the profound and prolific impact of a single donor, there’s nothing else like it in our circulating collection.”

A third of the fifty most-checked-out items in the collection are Tim Finn donations, Nishimura added. “That’s a really clear illustration of the incredible impact,” she said.

With a foundational comics, graphic novels and history of comics collection in place thanks to Finn, the library has been able to attract gifts from other donors. Architect Christopher Scholz P15, whose son attended RISD, recently donated a collection of French comics to Fleet Library. Journalist and hip-hop collector Bill Adler donated his extensive underground collection—an adults-only version of the genre—to the library in 2021 after receiving a drawing by a former staff member as a holiday gift from his daughter.

“The archive is so broad and it goes back so far,” Adler said of the library’s holdings as he made his own donation at the time. “I’m thrilled to make a contribution. The idea that folks I don’t even know will find joy and use in it is cool as hell.”

Finn’s donations—which built the “archive” Adler mentioned—include hardcover volumes from the Franco-Belgian comics tradition, a decision he originally made because European comics are usually published in hardcover collections, which make them more durable for circulation. Comics printed in the

United States as bound hardbacks started surfacing only in the late 1980s.

The European collection benefits RISD students, says history of illustration professor Jaleen Grove, because it gives them access to comics with a history and a publishing model different from the one most comics-loving Americans grew up binging.

The U.S. style of comics developed around an assembly line model, where large publishers divide up production jobs among many different artists and writers and then publish paperback single-issue tales. European comics tend to be published as entire books through a close collaboration between a stellar writer and a stellar artist, as a team, more like a graphic novel, Grove explained.

“Students get some examples of brilliant art and storytelling because the collection that was donated has some of the better-known artists in the canon of the Franco-Belgian tradition,” Grove said. Some examples include Rocco Vargas, Blacksad, Asterix, and a three-book set on Tintin and the art of its creator, Hergé.

But Finn has also donated collections of serialized American comics, like the first decade of Amazing Spider-Man and a popular 1990s Batman miniseries in book form. While many students have read individual issues of these popular series, Finn made available the mainstream American works so that students can access dozens of books collecting stories of these superheroes across a half century or more. And as “alternative” and comics-as-literature graphic novels have proliferated, culturally topical and award-winning works like Chris Ware’s Jimmy Corrigan and Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home have joined the collection as well, plus there is a small but growing selection of manga.

“I want to thank Tim for putting his collection forward and knowing that teaching examples are really necessary for RISD and our students,” Grove said, noting that the act of donating comics, from whatever tradition, is rare.

“There’s not many people who are willing to part with their comics—ever. They’re going to get buried with them.

The RISD Alumni Association is pleased to support Pulling on the Thread, a podcast hosted by Lois Harada 10 PR who takes an inside look at the studios, careers and innovative projects of RISD alumni.

Logo created by Suerynn Lee 12 PR

Exquisite limited-run works from internationally recognized alumni artists.

Proceeds from the sale of RISD Limited Editions go directly to supporting RISD students through the Student Opportunity Fund.

View the latest release at: alumni.risd.edu/limited-editions

From outer space to the Arctic tundra to the Mississippi Delta, Tavares Strachan creates work that “exemplifies the power of human ingenuity.”

Words by Jennifer Sutton

Courtesy of Perrotin, Portrait by Guillaume Ziccarelli

Courtesy of Perrotin, Portrait by Guillaume Ziccarelli

WHEN TAVARES STRACHAN 03 GL studied art at the College of the Bahamas in the late 1990s, his creativity and “go-getter attitude” were unmistakable, according to his classmate Christophe Thompson MFA 07 GL

“Tavares didn’t shy away from the potential of a project,” Thompson remembers.

The two hit it off, Thompson says, in part because while some of their fellow students expressed wariness about the unknown, he and Strachan did not. “We found that we were having all these conversations about possibilities,” Thompson says. It was like swimming: “Some kids look at water and say, ‘Oh, that looks scary.’ And some kids say, ‘I want to go in.’” Strachan, a RISD trustee, has been going in—all in—for more than twenty years. As a conceptual artist, he blends drawing, painting, printmaking, glass, sculpture and video with deep-dive scientific and historical research and a desire to elevate people and ideas overlooked by much of society. His breadth and flexibility, his confidence in bypassing boundaries, and his commitment to telling untold stories add up to work “that exemplifies the power of human ingenuity” and “pushes the limits of what is possible in art.” That’s according to the MacArthur Foundation, which in September 2022 awarded him one of its prestigious annual fellowships known as “Genius Grants.”

“I think I speak for a lot of folks out there who have been frustrated with the status quo and the way systems work,” Strachan says. “[The MacArthur Foundation] wanted something else. And they pointed at me.”

“Something else” is like when, in 2005, while still a graduate student at Yale, Strachan traveled to Arctic Alaska and carved a 4.5-ton block of ice out of a frozen river. He shipped it via FedEx to the Bahamas and displayed it at his former elementary school in a solar-powered glass freezer that he built in collaboration with scientists at MIT. This was The Distance Between What We Have and What We Want, a project that highlighted ideas of cultural and geographic displacement and recognized the Black polar explorer Matthew Henson, who was one of the first people to reach the North Pole but is usually overshadowed by his fellow explorer Robert Peary. Strachan’s subsequent trips to the Arctic culminated in Polar Eclipse, a sweepingly diverse exhibition at the 2013 Venice Biennale, where he led the Bahamas in establishing its first national pavilion at the event.

In 2009, Strachan began training at the Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center in Star City, Russia, learning to cope with the stress and pressure of simulated space travel. The training “was very much like a studio practice for me,” he told an interviewer at Frieze Seoul last fall, and the experience grew into a yearslong multimedia project titled Orthostatic Tolerance. Eventually, Strachan developed Enoch, a 3U CubeSat (nano-satellite) that contains a 24-karat gold bust of Robert Henry Lawrence Jr., the little-known first Black astronaut, who died in a supersonic plane crash before he was able to go into space. In 2018, Enoch was launched into orbit from a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket and is still circling the Earth.

“The idea of impossibilities has always been something I love.”

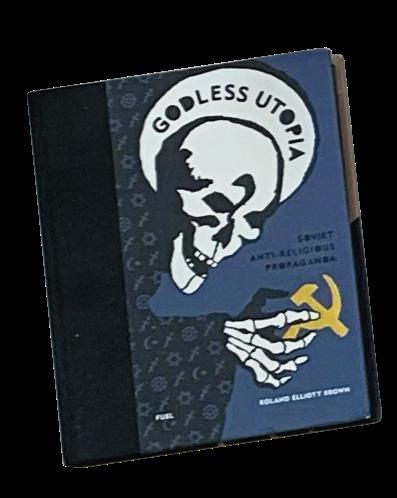

Much of Strachan’s work stems from his Encyclopedia of Invisibility, a 2,400-page leatherbound opus that documents people, events, and ideas that didn’t make it into the Encyclopedia Britannica he pored over as a kid. Among the more than 17,000 entries in the Encyclopedia of Invisibility are Henson and Lawrence; Sister Nancy, the first female dancehall DJ in Jamaica; and Mary Bonnin, the first female master diver in the United States Navy.

Strachan transforms individual encyclopedia entries into a startling range of objects, such as the life-size blown-glass sculpture of a diver submerged in a glass tank filled with mineral oil. Because light passes through the glass and the oil the same way, the diver is sometimes visible, sometimes not, depending on where the viewer is standing.

This revealing and uncovering are the foundation of Strachan’s work.

STRACHAN GREW UP in Nassau in the Bahamas, in a family of makers. His mother, Ella, was the oldest of thirteen siblings and worked as a seamstress. When he was five, Ella had a job making dresses for contestants in a beauty pageant; she made tuxedos for him and his older brother so they could attend the event by her side. “I believe I inherited a certain level of aesthetic tactical ability from her,” Strachan says.

As a kid, living on an island, Strachan could not go very far, but he dreamed of going to “the bottom of the ocean, the top of Mount Everest, the pyramids of Giza, the belly of a whale.” Every year, he participated in Junkanoo, the Bahamian street festival that evolved from West African traditions over hundreds of years. Groups get together to make elaborate, colorful sculptures and costumes. Strachan calls it “a staple of creativity in the Bahamian community” and “a collision between making and storytelling.”

The abundance of Junkanoo finds its way into much of Strachan’s two-dimensional work, which combines seemingly unrelated images within a frame: a rocket ship, a crossword puzzle, and Shakti, the Hindu goddess, for example. For the 2018 installation Six Thousand Years, Strachan erected soaring wall-sized grids of hundreds of entries from the Encyclopedia of Invisibility. Walking through the installation, viewers are literally surrounded by stories—an alternate universe of information.

Tavares Strachan The Invisibles (Jack Johnson), 2014-15 The Invisibles (Jack Johnson) is a series of vitrine sculptures. Photo by Tom Powel Imaging

At the College of the Bahamas (now the University of the Bahamas), one of Strachan’s professors told him about RISD and described how students “could make anything there,” Strachan remembers. He wanted to go, but it was a complicated decision. “When you’re from a poor family, you represent the village, and if you’re the one who could be the breadwinner for the village, you have to think deeply about how you’re going to operate in the world,” he says. “I remember thinking I should be an architect or an engineer, something that was still in the realm of making and building and was seen as more practical. But my father asked me, ‘Do you love those things as much as you love being an artist?’ I said no. And he said, ‘There’s your answer.’”

RISD helped shape Strachan as a person, he says: “It was a space where all kinds of making collided, where you were encouraged to think as much as you were encouraged to have a strong sense of materials... the ethics of making, the fundamental principles of artistry, the respect for process, the respect for tradition, and at the same time, disrupting all of that to make something new.”

Strachan’s wildly ambitious endeavors place him on a path parallel to those of the people and ideas he wants to honor, those who pushed beyond societal and cultural limitations. When the boundarystretching complexity of his own ideas strikes others as unattainable, he pushes forward. “When I was fundraising to move that piece of ice from the Arctic to my elementary school, a very supportive patron of mine wrote me a check, but as she did, she was saying, ‘This is not going to work,’” Strachan recalls. “The idea of impossibilities has always been something I love. When you’re a maker, you’re always making a thing that doesn’t exist yet.”

WHAT

was unquestionably disruptive and new. While earning an MFA in sculpture at Yale, he conceived Where We Are Is Always Miles Away, securing permission from the city of New Haven to excavate a 3,000-pound piece of sidewalk, parking meter included, where his car had once been ticketed.

His travels to the Arctic soon followed, as did his cosmonaut training in Russia and his establishment of the Bahamas Aerospace and Sea Exploration Center, where he conducts research, develops projects, and brings science and technology opportunities to his home community.

Throughout every project, Strachan is both a philosopher and a problem-solver, according to Mariko Tanaka, his studio director in New York. “He has more ideas than one can realize in one life,” she says. He gets a vision in his mind and is able to manifest it because he works well with figuring out what’s needed, step by step, to make it feasible and functional in the world.”

WHEN STRACHAN RECEIVED the phone call notifying him that he’d won the MacArthur Fellowship, he was in Seoul installing a show. He didn’t recognize the number, and thinking it was a prank call, he nearly didn't answer. Despite the exciting news, he found it difficult to share with family and friends. His father had died just a few weeks earlier. The combination of mourning a loss and celebrating an accomplishment reminded Strachan of where he came from. “It was my dad who really gave me permission to be me,” he says. “The intentionality I have as an artist comes from the conversation we had when I wanted to go to RISD.”

When Strachan contemplates a new idea or maps out a new project, the audience he thinks about is that young man, deciding to become an artist, and his childhood self. What stories will resonate with that kid and other kids who are told at a young age that they can do anything they want when they grow up? Many of Strachan’s exhibitions include sculpted neon glass tubing that spells out empowering statements such as “I am” and “You belong here”—pieces that not only hang on walls but also appear in site-specific installations such as a field of desert craters in Palm Springs or a barge floating on the Mississippi River in New Orleans.

“One of the things I hope an audience will get from my work is that they begin to find value in their own experience,” Strachan told an interviewer after he was named a MacArthur Fellow. “For them to go on their own journey. Because I am on a journey also.”

Words

Words

IMAGINE THE ARCTIC as a frozen sea surrounded by continents. The United States, Canada, Iceland, Greenland, Norway and Russia all border the Arctic Ocean, where thick, multi-year sea ice has historically formed the foundation of a rich marine ecosystem. Algae growing beneath the ice feeds the zooplankton that support the food chain up to seals, walruses and polar bears, all of which depend on ice for their reproductive success. Arctic Indigenous peoples have relied on these animals for food for millennia and use ice as a platform for travel between communities and to access hunting areas. The ice has also kept the region largely unreachable by ship except during short windows of time in the late summer, contributing to its remoteness.

Today, the Arctic is warming at four times the rate of the rest of the planet, and its sea ice has decreased by two-thirds since it was first measured in 1958. Studies predict that summers could be ice-free as soon as 2035 if greenhouse gas emissions are not radically reduced—contributing to a surging interest in the Arctic by northern hemisphere countries as a path for shipping lanes, natural resource extraction, commercial fishing, tourism and military activity.

Right: Sea ice near Resolute Bay, Nunavut, in September 2014.

In the past decade, marine vessel traffic in the Arctic has more than doubled. Ships will soon be able to bring lucrative commercial opportunities into regions where few have previously existed. While development can economically benefit many of the Arctic’s four million residents—about 10% of whom are Indigenous—it also marks a dramatic shift from the subsistence lifestyles and traditional values of many remote communities.

threatening some of her community’s most important subsistence traditions, especially the annual hunt for ugruk (bearded seal). She described a profound sense of loss that her son, already passionate about hunting, may never have the chance to hunt for seal if sea ice continues to disappear.

Climate change has already led to a rise in food insecurity in many parts of the Arctic, as animal migration patterns change and hunting grounds become inaccessible. While an increase in ships can lower prices for imported foods, they also pose additional risks of oil spills, debris, discharge, marine mammal strikes and critical habitat loss through underwater noise pollution and fragmentation of sea ice by icebreakers.

A tourist ship, in search of polar bears, leaves behind a trail of crushed sea ice off the coast of Spitsbergen, Svalbard. Marine mammals that rely on sonar and acoustic communication are particularly vulnerable to underwater noise pollution and can cease feeding behavior if disturbed.

As human activity in the Arctic increases, the need to adapt is inevitable. Understanding the long-term environmental and social implications of proposed development will be critical in ensuring that changes are made in the genuine interest of those who live there. Essential to this success is the involvement of Arctic peoples in deciding what happens in their homelands—the people who understand the changes already affecting the environment better than anyone else.

IN THE 1932 MOVIE I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, the protagonist, a decorated World War I veteran returning home to resume life as a civilian, gazes out his office window upon the bustling construction of a new bridge in downtown Los Angeles. Dazzled by the engineering feat, he neglects his banal duties as an office clerk and each day explores the bridge, admiring the impressive steel arches that would, in the real world, go on to carve their unique history in LA’s skyline.

This would mark the first of many appearances for the iconic Sixth Street Viaduct in film and television. Arguably, the most widely known is its cameo in Grease, when John Travolta roars along the cement-covered LA River in the movie’s culminating drag race.

Unfortunately, the viaduct had been plagued from its birth by a fatal alkaline in the cement that steadily degraded its structural integrity. It became increasingly clear that demolishing the original structure and starting from scratch was inevitable. In 2016, after 84 years, the viaduct met its demise, beginning a new chapter for an infrastructure project as rife with challenge as it was with opportunity. When Michael Maltzan BArch 85/P 24 was chosen as the architect to lead the viaduct overhaul, he drew from lessons he learned at RISD.

“This may be a form of cultivated naivete, but when I approached this project, I really went back to something that RISD instills in you as a ‘maker,’” says Maltzan during a Zoom call from his office in LA.

“RISD taught me to push aside the idea of a preconceived solution, and to believe that the most important things are to begin and to trust your instincts and your experiences to help guide you through that process.”

The roughly $588 million project is said to be the largest bridge project in the history of LA. It was funded by the Federal Highway Transportation Administration and the California Department of Transportation, as well as city funds. The viaduct, which connects the downtown arts district to Boyle Heights, offered a tangible opportunity for Maltzan and his collaborators to craft a very literal bridge between communities, and to do something that

has grown increasingly rare in the United States, post–World War II—build infrastructure that can be a source of shared pride among the people who use it and live near it.

After a few years of construction, the new viaduct finally opened last year to universal acclaim and widespread excitement among LA’s residents. A safer, more modern, and more accessible structure, with green spaces (a twelve-acre public park below the bridge) and accommodations for bicyclists and people with disabilities, the new bridge strikes a balance between the competing forces of nostalgia, progress and potential. Maltzan made sure to include arches that pay tribute to the most distinctive characteristic of the original structure.

Also known as The Ribbon of Light for its multiple arches, which light from below, the viaduct has become a destination spot, attracting walkers, runners, bicyclists, skateboarders, families out for an evening stroll, and photographers looking to capture images of the arches and LA skyline backlit by the setting sun. “The bridge is really meant to be a civic armature, to turn infrastructure into something that weaves together the city ... [and] connects communities,” Maltzan says.

The Sixth Street Viaduct also represents a return to an architectural philosophy dominant in big cities prior to World War II, when designers were influenced by the City Beautiful Movement—design and urban beautification to inject a sense of humanity, creativity and cultural pride into areas of cities where residents had too often been forced to endure overcrowded tenements and shoddy planning.

“After World War II, there was a diminished sense of a collective physical, civic space, particularly as so many people fled the cities for the suburbs. That’s starting to change, and you can see it in projects in New York City and in San Francisco, and now here in Los Angeles with the Sixth Street Viaduct,” Maltzan explains.

“There’s a renewed understanding that infrastructure doesn’t have to be the thing that tears cities apart and separates communities but can be something that in fact weaves those communities and cities back together again.”

“That act of coming together in a collective way is where architecture can be at its very best...”

“Maltzan’s firm is an example of the impact architecture can have on the greatest social challenges of today.”

Maltzan says he has tried his best to recreate the dynamic he experienced at RISD within his firm, Michael Maltzan Architecture. That cross-pollination of different creative disciplines that RISD offers prepared him for the wide range of professionals he collaborates with as an architect. He largely credits his experiences at RISD for helping shape his unusually diverse portfolio, from breathtaking single-family homes to affordable multitenant housing to art museums and large-scale infrastructure challenges like the viaduct.

“There are so few places in the world where you can feel the collective sense of purpose that you feel at RISD, driven by a commitment to making things,” Maltzan says.

“I have always been attracted to that amazing culture where everybody is committed to making a creative contribution, and it all goes back to my Freshman Foundation at RISD, where painters, sculptors, graphic designers and architects were connected by the fundamental process of learning how to see something in your head and then making something from that which is meaningful to you,” he adds.

An enthusiastic art and drawing student in high school, Maltzan began his journey to RISD when he was working part time for local architects who had all gone to RISD and eventually encouraged him to apply.

“After visiting the RISD campus, I came away feeling like it was a culture and a place that I felt connected to in a way that I had never felt in any other areas of my life. After that first visit, I couldn’t get the school out of my mind,” he recalls.

Maltzan’s firm is a modern example of the impact architecture can have on the greatest social challenges of today. While the industry has a long if somewhat uneven history of trying to address global issues surrounding social justice and inequality, the notion of community has been present in the industry since the transitional era between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, when architecture throughout Europe was largely focused on creating innovative forms of housing to address the emergence of increasingly undeniable socioeconomic forces, such as a migration from rural areas to bigger cities. Many projects were aimed at affordable housing in which thoughtful architectural design had seldom if ever existed.

Despite the diminished capacity for civic spaces in the United States post–World War II, there were progressive initiatives, such as California’s Case Study House Program, that sought to harness in a domestic capacity the materials and technology that had emerged during the war, especially new technologies of construction and the use of glass, steel, reinforced concrete and synthetic materials. The program brought together architects and designers to create innovative, affordable single-family housing for soldiers returning home. By the 1960s, the environmental movement impacted the building boom and began to influence modern architecture and design in a manner that has helped pave the way for modern sustainability philosophies and methods—the advent of the first solar buildings, for example, were born out of this movement.

“Architecture’s legacy of deep involvement with social justice issues helped lay a foundation for the moment we’re living in now, where many of these

concerns—[sustainability, affordability, justice]—have become not just pressing, but actual crises,” Maltzan says. “So it’s only right that architecture would be called on to grow its responsibility and relationship to these challenges.”

This is nothing new for Maltzan. When he opened his architecture and urban design firm in 1995, there was a sharp focus on promoting the philosophy that architecture can play a vital role in creating progressive change, particularly when it comes to shared spaces and how people interact with them. Maltzan says his firm is committed to meeting challenges in many different contexts to confront cultural, social and political struggles. His projects are consistently informed by an interest in the space that is defined by the buildings and how people engage with them, not solely by the sculptural forms of the projects.

“What motivates me is what causes individuals or communities to make connections and the ways in which architecture allows separated people and constituencies to be woven together,” he says.

That sentiment may be commonly expressed in architecture as an industry, but putting it into practice requires tremendous research, collaboration and humility, which Maltzan achieves by working closely with the communities that will actually be engaging with his work—an obvious but often overlooked layer to civic and infrastructure projects. Maltzan believes that comes before the technical and cross-disciplinary broader vision.

“We always begin by developing a conversation around what the common ambitions are,” Maltzan explains. “We find the common purpose before we talk about the specifics of all the different collaborators and technical necessities.”

Maltzan doesn’t consider himself an artist, but thanks to RISD his work is more heavily influenced by artists and art history than by architects. He believes that despite their vast differences, the connective tissue binding painters, sculptors, graphic designers and architects is the passion to express something of consequence about the world they live in.

His appreciation for the arts helps shape how he selects some of his most exciting projects. He’s looking forward to working on a performing arts complex at the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York, which will include a 750-seat theater and a 1,200-seat symphony hall.

“I have always loved performance spaces since my beginnings in architecture, and these are two theaters that are very important to me,” explains Maltzan. “While we’ve done some smaller theaters, I haven’t had an opportunity to work on one at this larger scale, and they’re such special spaces. If you look at the history of theaters, they hold an extraordinary place in architecture’s legacy; they are a place where people can connect.

“That act of coming together in a collective way is where architecture can be at its very best, and so this [performing arts] project means a great deal to me.”

Gabrielle Bullock is creating an open-air museum along Crenshaw Boulevard in Los Angeles, the largest Black public art project in the US.

Words by Doug Daniels

Words by Doug Daniels

THE HISTORICALLY RICH Crenshaw Boulevard weaves 23 miles through a variety of ethnically distinct neighborhoods in South Los Angeles, a thoroughfare that serves as a powerful symbol of cultural diversity. The most famous stretch, known as the Crenshaw District, the largest Black community west of the Mississippi River, is a vibrant epicenter of art, culture and commerce.

The Crenshaw District has been called the spine of LA’s Black community.

When the city approved a light-rail line that would cut directly through the Crenshaw District at street level, a disruption to the neighborhood’s center of commerce, frustrated community members responded by proposing a revitalization initiative of their own, known as Destination Crenshaw—a 1.3-mile-long outdoor cultural and arts experience that celebrates the proud history of the district and Black artists.

Enter Gabrielle Bullock BArch 84, principal and director of global diversity, Los Angeles, at the prestigious architecture firm Perkins and Will, one of four architects hand-selected to lead what will be a “thriving commercial corridor linked by architecturally stunning community spaces and pocket parks,

hundreds of newly planted trees and over 50 commissioned works of art.”

“The community decided that they wanted to create a destination experience that sends a clear message: ‘We are here, we are staying here, this is our culture, so come visit and learn about it,’” Bullock says.

Unlike the light-rail infrastructure project, Destination Crenshaw, currently underway, is unique because “from the start, we’ve been working in lockstep with the community instead of just telling them what we plan to do, which challenges the status quo of what architects typically do,” Bullock says.

Sankofa Park, the first major component of this $100 million public-private initiative, will open with a public celebration in fall 2023.

“The [Crenshaw] community’s creative input,” she explains, “has been a central guide” of the project, which will be a catalyst for economic development, job creation and environmental healing, all while elevating Black art and culture.

For more than three decades, Bullock has devoted her work to addressing social inequity and cultural awareness in architecture. She’s been instrumental

in the design and management of an incredibly diverse portfolio, ranging from health-care industries to educational institutions and museums, including the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center.

Only the second Black woman to graduate from RISD with a degree in architecture, Bullock was appointed director of global diversity at Perkins and Will in 2013, becoming the first Black woman to hold such a position. Over the past decade, the firm has significantly improved its diversity and inclusion efforts through new initiatives and by conducting training and workshops on topics like cultural competency and inclusive design.

Bullock’s role in promoting more inclusivity in architecture is a key component to modernizing an industry that has traditionally been dominated by white men. In fact, Black women currently make up a mere 0.2 percent of licensed architects in America—fewer than 600 total. Bullock wants to improve statistics like this so that communities are represented in the design teams and architects who are creating the buildings and spaces with which communities engage.

BORN IN HARLEM, Bullock moved with her family to the Bronx in the late 1960s—the first Black family to move into the majority white Riverdale neighborhood. As a young girl, she and her sister would ride the subway throughout the city to visit relatives and friends, and that early exploration of New York exposed her to the gaping chasm between living standards in various areas of the city.

“When I was young, I had a visceral reaction to the public housing developments I saw,” Bullock recalls. “They were very inhumane. Tiny windows, cinder block walls, no landscaping, no trees—they looked like prisons. At age 12, I decided I wanted to be an architect to change the way people lived.”

Bullock said she never had a plan B. Becoming an architect was her sole career focus. She’s quick to offer praise and credit to the strong women in her family who ensured she could pursue whatever she wanted to do as long as she worked for it. Her talent and that encouragement helped carry her through RISD, making her the first person in her family to graduate from college.

“My values, combined with my experience at RISD, have influenced where I have worked throughout my career, what kind of projects I choose to work on, and the types of firms I work for,” she says.

After leaving RISD, Bullock returned to New York in the mid-1980s to fulfill her childhood vow of changing how people in her city live. She worked at several firms that specialized in low-income housing, but as recession gripped the country, three firms she worked for succumbed to economic pressures and folded. Frustrated but undeterred, she found her way to Perkins and Will, which has a reputation for innovation and for focusing on sustainability. Though she was no longer working on public housing, she felt good about her projects at Perkins and Will.

“I had no interest in the shiny object buildings,” Bullock explains, referencing the architectural trend in the 1980s and 1990s in large cities. “I didn’t want to do skyscrapers; I wanted to do some good, and working on medical facilities with Perkins, for example, was part of that.”

FOR DESTINATION CRENSHAW, Bullock noted that incorporating community priorities was essential because the project was not to design a building but to create a civic space.

“We understand that we aren’t designing a building. We’re designing an experience,” Bullock says. “We’re designing parks, outdoor exhibition space, and walking paths, and we wanted every aspect to reflect what we heard from the community, which was a theme of resilience.”

Even the grass selected to fill the open spaces sends a message of resilience and recognizes Black American history. The underlying design theme was derived from the giant star grass and its rhizome root

structure, known as Bermuda grass in the US. It was used as slave ship bedding and became synonymous with this community’s migration from Africa and points east and south.

“That grass became our design theme for the entire corridor. The paving mimics the root system, and the shade structures mimic the grass. And this will all be the backdrop for the Black artists and cultural figures we’re displaying and paying tribute to.

“The goal is to avoid a cultural erasure,” Bullock says.

To this point, Bullock believes this project will have true staying power, evolving along with the area as it undergoes the inevitable ethnic, cultural and economic shifts that most neighborhoods naturally experience over time. It is designed to serve as a catalyst for economic development. With an unprecedented commitment to local hiring and robust small-business support, the project will build a pipeline of Black talent in the construction trades, support entrepreneurship and promote creative talent through programming for years to come. As a result, the community will directly benefit from the improvements it makes together.

“There can sometimes be an architects-as-saviors dimension to community projects, where a firm will come in and exert too much control based on their specific vision,” Bullock says.

“The purpose of Destination Crenshaw isn’t to reimagine or re-create an already thriving community—the idea is to celebrate and enhance it.”

“The Crenshaw community’s creative input has been a central guide.”

Lina Sergie Attar MArch 01 stood before a towering pile of rubble, unable to fully absorb the destruction.

The Hatay Province in southern Turkey and its capital city of Antakya occupy a rich slice of human history, home to one of the Roman Empire’s largest cities and an early center of Christianity.

The area’s ancient churches, mosques, and other archaeological treasures have long been revered by scholars and laypeople. But many of them have been reduced to rubble after last winter’s devastating earthquakes in Turkey and Syria. The tragedy left nearly sixty thousand people dead and another 1.5 million homeless. The structural damage was breathtaking, with a price tag of nearly $110 billion.

But nothing compares to the human toll of the natural disaster for a population already suffering immensely from a man-made one. Turkey has seen a massive influx of refugees as the Syrian civil war rages on toward its thirteenth year, and the displacement of those fleeing war has now been immeasurably exacerbated.

For Attar, a Syrian American architect and writer who founded and serves as the CEO of the Karam Foundation, this latest catastrophe poses fresh challenges for her refugee aid and educational organization. In the immediate aftermath of the earthquakes, Karam (which means “generosity” in Arabic) moved quickly to provide food, shelter and other necessities. It also helped connect struggling communities with mental health services.

The organization managed to distribute over 8,800 diapers, 2,000 bread bags, 1,500 bottles of water, 350 parcels of food, 250 thermal blankets, and 50 mattresses. Today the foundation supports a number of camps by serving daily meals to thousands of earthquake survivors, and it hosts pop-up tents offering creative and innovative activities, games and movie nights to help ease the suffering of the displaced children.

“I honestly have not been able to process the earthquake damage,” Attar says a few days after she returns home to Chicago from Turkey. “My brain

Lina Sergie Attar worked to find shelter for those displaced by the recent earthquakes in Turkey and Syria, and her Karam Foundation continues to help refugees design their own futures.

Photo: NurPhoto, gettyimages.ca

Photo: NurPhoto, gettyimages.ca

kept telling my eyes, ‘You’re not seeing reality.’ It’s so heartbreaking to see all these peoples’ homes and lives completely wiped out overnight.”

Beyond providing food and supplies, Karam also stepped in to assist in a number of areas outside their typical purview, offering evacuation support, temporary shelter, and cash assistance to families in Hatay Province and Syria.

ATTAR HAS A DEEP affection for the people in the region she once called home. Her foundation, despite its recent short-term response to the earthquakes, is primarily focused on sustained long-term support of the refugee population. Karam currently has two community educational centers in Turkey, called Karam Houses, for young Syrian refugees displaced by the war.

“Our goal is to help shape ten thousand young Syrian leaders by 2028,” Attar says. “We define leaders as every young refugee we’ve empowered to either complete their higher education or learn the skills to secure dignified work,” she adds. “We’re putting them on the pathways to their full potential wherever they ultimately land.”

Born in the US, Attar moved with her parents back to their home country of Syria when she was twelve and stayed there through college before coming to RISD for graduate school. When she started her nonprofit in 2007, based in Chicago, she never imagined the organization would evolve into the highly impactful global force it has become.

The 2020 RISD Serves Award recipient, Attar was inspired by her father’s charity work in Aleppo, the Syrian city that erupted in revolution in 2011—a conflict that has now displaced more than fourteen million Syrian refugees. The revolution and continued civil war both raised the stakes and dramatically expanded the foundation’s potential reach.

“Initially, the idea was to focus mainly on the Arab American community here in Chicago and offer a new way of thinking about charity in a comprehensive and long-term way,” Attar says. “I was fascinated at the time by some of the emerging innovations in charitable giving, like microloans, that could help underserved or displaced communities not simply get the bare essentials but really rebuild their lives.”

Attar quickly decided she wanted to focus on Syrian youth and offer them opportunities to learn skills and develop creative and artistic talents in the foundation’s Karam House community centers. She believes her inexperience early on creating and running a nonprofit was an unexpected advantage. While other nonprofits often follow a cookiecutter approach, Attar and her small group of initial volunteers had no choice but to be creative and innovative from the start—a skill set she credits RISD for giving her.

“I learned at RISD that design curricula and exposure to creativity and the studio structure all help young people focus on the present moment. We quickly realized that the studio approach created the space for our refugee students to process their trauma,” Attar explains.

To translate her philosophy into a tangible program, the foundation partnered with the Massachusettsbased NuVu Innovation School to create a curriculum that blends design, art and technology training free of charge. Attar says the collaborative spirit she found infectious at RISD also laid a powerful foundation for her approach to building her organization in close concert with the community she was determined to help.

“The architecture program at RISD definitely showed me the power of listening and the need to coauthor your designs and your solutions with the community impacted by new architecture—otherwise it won’t actually work in practice,” Attar says. “So many of the failures we see in humanitarian aid efforts can be traced to failing to coauthor a vision and road map with the people on the ground who will be directly impacted.”

Karam House curricula and workshops are tailored in Arabic, and students have access to tools, studio space, woodshops, Wi-Fi, computers, professional mentors, a kitchen and a library, along with space to socialize. Attar explains that spaces become second homes for many of the young people they serve and offer opportunities to socialize in a safe environment they might not otherwise have access to. And, consistent with the organization’s ambition to offer long-term assistance, former students and kids who worked and learned at the Karam Houses are

“Our goal is to help shape ten thousand young Syrian leaders by 2028.”