12 minute read

Feature

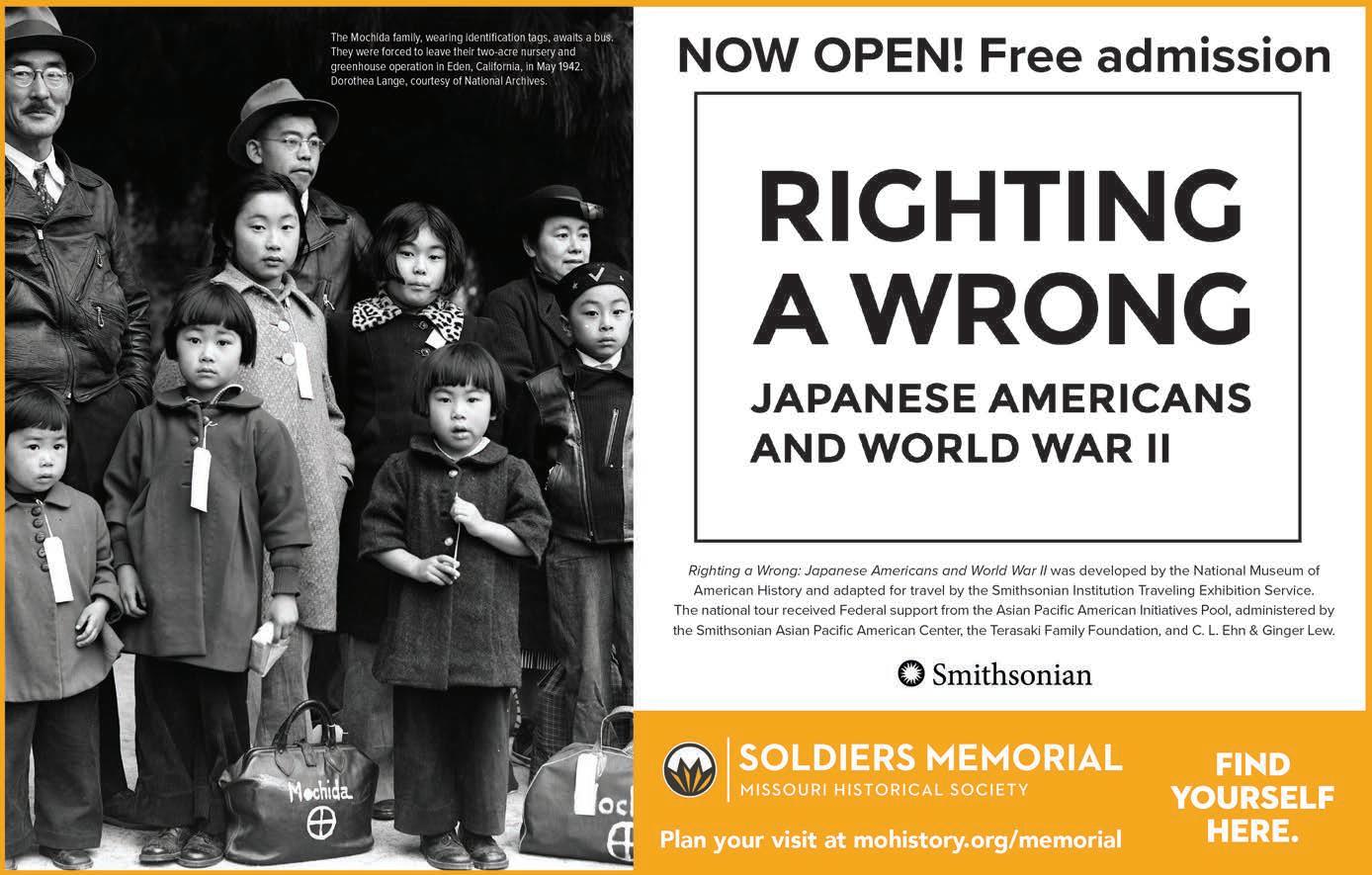

Advertisement

Nation At Louisa Foods, a melting pot of workers produces the quintessential St. Louis dish

BY VICTOR STEFANESCU

August 8, 1994, was a big day for Denis Krdzalic — he still remembers the date. That’s the day for him: the day he came to America.

Krdzalic is from Bosnia, like many who now call St. Louis home. He was studying at the University of Zagreb in Croatia as a war that killed an estimated 100,000 people ripped through his country.

Declared an alien of Bosnia, Krdzalic, 23 at the time, was referred to American refugee services and moved to St. Louis. He couldn’t even find the city on a map.

“And I’m really good at geography,” Krdzalic says.

Knowing nothing about the city, Krdzalic found a forklift gig in shipping and receiving at Louisa Foods about 40 days after he arrived.

The pasta company was a fairly small operation back then. Krdzalic says about 60 workers operated a factory floor now run by a diverse workforce of roughly 250 immigrants and St. Louis natives. They push out one of the city’s most recognizable dishes to far reaches of the country.

The toasted ravioli you are probably thinking about right now most likely came from Louisa. Whether it’s the Super Bowl party t-ravs grabbed hot out of the oven at kickoff or the sober-you-up fried pasta you got at the bar last week, it all starts at the 1918 Switzer Avenue factory in Jennings.

Louisa Foods didn’t invent travs — the company’s management wants that to be clear — but they make the most iconic ones, even with the rise of national competitors.

“We’ve never tried to be the biggest … that has never been our goal, to be the biggest,” says Tom Baldetti, the third-generation owner of the company. “We’ve tried to make it as good as we can.”

Fernando Baldetti, an Italian immigrant and Tom’s grandfather, started Louisa by hand-making traditional ravioli in the basement of Garavelli’s. The cafeteria-like Midtown restaurant, where he was a partner, shuttered in the ’70s. Then John Baldetti, Fernando’s son, bought a ravioli machine in New York and began making ravioli as the Louisa brand in a two-family flat in Baden.

Out of the residence, the Baldettis were delivering their ravioli to restaurants across the metro area. Back then, food distribution juggernauts like US Foods and Sysco were less dominant, so restaurants frequently ordered their ingredients through local suppliers such as Louisa.

Louisa’s ravioli wasn’t “toasted” by the Baldettis until about 50 years ago, according to Pete Baldetti, the plant manager at Louisa. Then, a customer asked for it to be breaded, and things changed.

“So, they bought like a little tiny thing,” Pete Baldetti says. “It’s like a little round tunnel that turned on wheels. It was like a chicken breader I guess.”

Going from that tiny chicken breader to today’s factory with Italian-made machines the size of trains, Louisa has grown its brand, and with it, the notoriety of the toasted ravioli. The company eventually moved to another Baden facility, and then it’s current Jennings plant in 1989, attracting workers like Krdzalic with it.

Two days before Krdzalic started driving forklifts at Louisa, he was washing windows, trying to make some cash. He came to America single and found a place to live in south city.

After a successful interview with John Baldetti — the owner of Louisa Foods at the time — rdzalic worked his first shift on September 19, 1994, another date locked in his mind.

In Krdzalic’s early days there, he biked to work. All he had to navigate St. Louis at the time was a printed map someone had given him, and he followed a wandering bus route that zigzagged through the south side.

“I would ride, but I didn’t know any shortcut because of how the bus [ran],” he says. “So, it took me about 50 minutes.” ver time, rdzalic figured out those shortcuts and began to settle into his new city. He was doing basic, entry-level work at Louisa when he began, but he felt challenged at work as he struggled with an unfamiliar language, culture and people. That’s what made him stick with the company.

“I stay long because I start moving really, relatively fast to the different kinds of jobs, the different responsibilities — every time more and more responsibility,” Krdzalic says. “So it’s [a] challenge for me, and I like that.”

Krdzalic worked eighteen months before getting a first promotion, and that’s about the time he ate his first t-rav. And he liked it. t’s so specific for idwest and everything,” Krdzalic says. “I think it has some kind of appeal …

Continued on pg 15Denis Krdzalic (center) with Tom Baldetti, Chef Paolo Pittia and Pete Baldetti. | ANDY PAULISSEN

Once made in the Baldetti family’s flat, Louisa’s t-ravs are now produced in Jennings and shipped around the country. | ANDY PAULISSEN

T-RAV NATION

Continued from pg 13

it’s a great product.”

But in his early months at Louisa, he took home the company’s lasagna, not toasted ravioli, because it was easy to make.

“I came here as a single guy, you know, just me,” he says. “We are coming from parts of the world [where it’s] not too custom for males to be really good and familiar with the kitchen. … Just, I need to put it in the oven. It’s like big deal for me, I can go all week.”

Climbing his way up, Krdzalic became a living Wikipedia of Louisa — it seems like he knows everything about the company. He also took on the role of an unofficial interpreter. hen first got here — retired from the Air Force in 2003 — Denis was a second-shift supervisor,” Pete Baldetti says. “And that shift had probably 75 or 80 percent Bosnian people, so it really made it so he could be very effective in the communication and everything.”

On a recent morning on the windowless, timeless factory floor of Louisa, rdzalic points his finger at workers huddled over a production line.

“Mexico, Bosnia, Jennings, Jennings, Venezuela … Nigeria and Myanmar,” he says, describing the varied nationalities of those shifting boxes of ravioli into bigger boxes.

Krdzalic, 50, is now the production manager at Louisa. Every shift, he finds a way to communicate with production-floor workers from about 30 countries, whether it be through pushing a thin vocabulary to its limit or using hand signals. In that process, he has stretched his own international dictionary.

“Every time somebody calls with a foreign language, they transfer it to me, like I know 50 languages,” Krdzalic says.

And just about everyone else at Louisa has grown their vocabulary, out of necessity.

“I have a guy in the freezer, Korean, who knows at least twenty Bosnian words,” Krdzalic says, shouting over the constant hum of big machines. “He knows probably 50 with the bad ones.”

From ravioli being stamped out, to boxes of oven-ready ravioli rolling off the line, all the steps involved in making a Louisa toasted raviolo occur on one uninterrupted line.

“Nobody knows who invented toasted ravioli,” says Tom Baldetti. “I think I do know that we’re the first ones to make a continuous process.”

All the pieces — and workers, with how they communicate — need to be synchronized for things to work. The first pieces, including raw ingredients such as diced vegetables, shredded parmesan cheese and ground beef, start off in vegetable, cheese and meat rooms steeped in the aromas of their ingredients.

Krdzalic reminisces back to when workers would set up shop in the vegetable room, hand-peeling onions for the next day’s production. Although onions come to the factory pre-peeled now, Louisa products start with the fundamentals. Mushrooms are inspected by hand when they arrive, vegetables are cut fresh, and 15,000 pounds of cheese per shift gets grated through a two-step process, he says.

Many of these ingredients converge in a production kitchen. Unlike your kitchen, there aren’t any stovetops, toasters or Whirlpool ovens, but rather 500-gallon tanks that can cook off up to 3,000 pounds of filling each batch, according to Krdzalic, who moves aside for workers carting heavy tubs of the ingredients through the room. Walking out of the kitchen, you see the lines.

A handful of production lines snake through the busy factory. The scene feels a little like a Willy Wonka factory. Walking around, you come inches from machines heated to hundreds of degrees and occasionally have to step over pipes. The company pushes out 40,000 pounds of breaded ravioli per shift.

Conveyor belts and rotors push the pasta from one end of a line to another, through Italian-crafted machines that cook an array of products, including gnocchi and tortellini.

T-ravs start as dough. Flour flows from a ceiling duct into automated mixers set on a platform that rises above the production floor. The combination then gets “mixed, mixed, mixed,” as Krdzalic says, and sent to each line.

The dough lands in extruders that squeeze out uniform sheets. For the t-ravs, it takes two sheets of dough to encase the filling, which is inserted by pistons. That’s how Krdzalic says it should be.

“Some companies, they cheat,” he says. “They make one single pasta. They flip it over and they call [it] ravioli. … That’s a different kind of pasta.”

Custom-made Italian dies then pop out uniform ravioli. Louisa has shelves of these antique dies ready to go. Along with other parts, they get tweaked to custom specifications by the company’s mechanics, Krdzalic says.

“We will buy some stuff and we will modify it,” he says. “That’s nice, to be part of something that it’s, no, it’s just not like blasting ravioli.”

The individual ravioli travel along the line and into piping-hot blanchers. Workers stand by the blanchers, making sure nothing goes wrong. Then, the cooked ravioli moves through the batter and breading, a particularly Midwestern touch.

From there, the ravioli travels through a centerpiece of Louisa’s factory floor: a spiral freezer. Added to the factory in 2004, the freezer can harden t-ravs in about 20 minutes, Krdzalic says.

The freezer is contained in a person-less room that looks like an archetype of the North Pole. Snow-like moisture latches onto every surface in the room, illuminated by a blue-white haze. Large fans, which aid the cooling sys-

Louisa’s green boxes of t-ravs are a familiar sight in grocery stores. | ANDY PAULISSEN

tem, make things loud.

“[In] wintertime, you will have more icicles and ice,” Krdzalic says, opening a door to reveal the arctic scene. “In summer … it will feel like Siberia.”

Krdzalic answers the main what-if question before it is even posed.

“If you turn [the fans] off, it’s actually bearable,” he says. “You can survive here probably five hours. The fans on, maybe fifteen minutes.”

Next the ravioli moves to boxes and workers. A woman grabs green boxes of toasted ravioli for retail sale in pairs and swings them into bigger cardboard containers with skilled form.

Unlike the toasted ravioli that get sent to local restaurants and national chains with fryers, t-ravs in the green boxes are meant for home-cooking, and get flash-fried for about fifteen seconds to be oven ready.

Once, Krdzalic says, the macro fryer these t-ravs roll through randomly released a fire-suppressant system when he was right by it.

“I told [a] guy, ‘I thought it’s gonna be like an instant, freaking, you know,” he says about the explosion he expected. “[I] was like one yard away. I just walked out.”

In Krdzalic’s new position, it’s his job to respond to crises like this pseudo-fire and oversee production — a tough role.

“We’re just trying to make it so that he doesn’t die,” Pete Baldetti jokes.

During Krdzalic’s career at Louisa, life has changed for him. He has a wife and two kids now, and he lives in south county. He takes a vacation every year, exploring St. Louis and the United States — or rediscovering Europe.

“Every year, I go on vacation, because my father taught me that, and I’m from Europe,” Krdzalic says. “Your vacation is [a] sacred thing.”

But a lot, too, hasn’t changed. Every day after work, as Krdzalic has done since getting a car, he just sits for a minute.

“If I’m close to four o’clock, then I will listen to the news,” he says. “If it’s already past four o’clock, then I will switch to the music, and I will sit for about a minute, minute and a half. And I have this satisfaction that we did something today, that I made something, that I resolved something.”

If Krdzalic ever loses that feeling of satisfaction, he says, he will leave Louisa. But in 27 years, he hasn’t, and that goes for his love for the company, too.

“Every time I go to any stores to get my beer or something, I always make a detour around the frozen food, and I check Louisa retail section and see what is missing or what, how they look and what’s the date there,” he says.

So, Krdzalic will continue to lead Louisa’s production floor, supervising workers who, like him, came to the country with nothing, crafting a product which brings St. Louis pride: toasted ravioli.

“It’s something so American,” he says. n