Emma Amos, Camille Billops, Vivian Browne and May Stevens

1965 - 1993

JUNE 4 - AUGUST 20, 2021

Friends and Agitators provides a window into the intersecting lives and friendships of four extraordinary artists represented by RYAN LEE Gallery and the significant community with which they surrounded themselves. These artists lived during a time of tremendous change and were an integral part of the founding of the Soho art scene in 1960s New York.

Emma Amos, Camille Billops, Vivian Browne and May Stevens were artists, feminists, civil rights activists, and community builders. Each fought hard for recognition and inclusion over the entire course of their respective careers. They believed deeply in their own art and in each other, and each kept significant archives and documentation on their work and activity. It is largely due to their own documentation that we have been able to mine the intersections of their lives and art in this exhibition and catalogue.

There are several artists whose contributions to the Soho art scene are immeasurable, and whose connections to RYAN LEE Gallery artists we have come across many times in our research. This exhibition and catalogue is by no means a comprehensive look at the Soho scene in the 1960s and beyond. Rather, the work of many artists and peers in addition to these four would be relevant to include in exhibitions and catalogues much larger in scope than this one.

I would like to give special thanks to the following for their ongoing support and enthusiasm for this exhibition and for granting us access and loans of private archival material: Nick and India Amos; Dion and Mary Hatch for the extensive Hatch-Billops archives; Vickiy Strutt-Hackman, Jon and Ken Hackman; and Patricia Hills and Emily Whitfield.

Special thanks goes to Ethel Renia for her diligent research and for writing most of this exhibition catalogue. Thank you also to Jordan Karney Chaim for her written contributions and to Daisy Fornengo, Daniela Ramos, Derek Piech and Amir Badawi who all worked on the exhibition with my gallery partner Jeffrey Lee.

It is with great pride and joy that we reunite, celebrate and exhibit these friends and agitators—together again.

Mary Ryan June 2021

The exhibition and catalogue Friends and Agitators: Emma Amos, Camille Billops, Vivian Browne and May Stevens, 19651993 follows the lives and works of four remarkable artists Emma Amos (1937-2020), Camille Billops (1933-2019), Vivian Browne (1929-1993), and May Stevens (1924-2019), whose intertwined careers, activism and friendships helped shape the Soho artist scene as a space for civil right and feminist activist artists in the 1960s and beyond. The impetus for the exhibition came from the gallery’s growing realization that these four women—all of whom are represented by RYAN LEE—were highly important figures in each other’s lives and careers, as friends, peers, and supporters. The catalogue traces their lives from their beginnings in Soho in the 1960s to Browne’s death in 1993. She was 64 years old.

Amos, Billops, Browne, and Stevens were part of a network of women artists in New York that blazed trails for the generations of artists and activists who followed. The extent of their activities is still coming to light, as exemplified by the recent revelation that Amos and Stevens were original members of the radical feminist art troupe the Guerilla Girls. The contributions of these four artists point to the diversity and divergence of the art of the civil rights era. There was no monolithic feminist or black art, and even as these artists supported each other, they often disagreed on the best approaches to “progress.” The importance of their work as artists and activists during the 1960s and 1970s was ultimately recognized in the seminal 1985 exhibition, Tradition and Conflict, Images of a Turbulent Decade 1963-1973,

curated by Dr. Mary Schmidt Campbell at the Studio Museum in Harlem. It was the first time all four had shown together.

Together, the four artists participated—in different combinations—in over 100 joint exhibitions from 1965 to 1993. Though these artists struggled to break the glass ceiling and get attention from museums and mainstream art galleries during their lifetimes, they had a rich exhibition life largely generated by their own network of artists and friends. This network of like-minded artists and artistic community is one that each artist championed in her own way. Stevens spearheaded the New York feminist movement and founded crucial exhibition spaces and community gathering points in Soho. Billops dedicated a considerable amount of her time, money and career to preserving and championing the activity of black New York-based artists from the 1970s on. Amos and Browne both straddled the feminist and black power movements, becoming involved throughout their lives in organizations such as the feminist Heresies Collective and the SOHO20 gallery, as well as Spiral, the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition (BECC) and Action Against Racism in the Arts, among several others. Amos took on leadership roles in Heresies, and Browne, a lifelong educator, pushed for increased accessibility to arts education in New York City schools.

The work of these four artists range an array of media and styles. Though Amos, Browne, and Stevens are identified primarily as painters, Billops began her career as a ceramicist and later

became deeply involved in filmmaking. All four women made prints—Amos and Billops were prolific and wildly experimental printmakers, while Stevens and Browne made a smaller number of prints throughout their lifetime. Amos was also a weaver and frequently included textiles in her work.

Though these artists faced discrimination and their art was generally overlooked throughout much of their lifetime, curatorial interest has picked up in recent years, as demonstrated by the recent inclusion of Amos, Billops, Browne, and Stevens’s art in groundbreaking exhibitions such as the Brooklyn Museum’s 2014 Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties, and 2017 We Wanted A Revolution: Black Radical Women, 19651985. At the time of this writing, Amos’s work is currently on view at her career retrospective, Emma Amos: Color Odyssey, which was organized by the Georgia Museum of Art in 2021 and will travel to the Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. May Stevens’s work is currently on view at SITE Santa Fe’s 2021 May Stevens: Mysteries, Politics, and Seas of Words.

In the 1960s, Soho’s now-famed artist lofts were not zoned for human occupation. Most artists, attracted by the low rent and the large spaces, lived and worked there illegally. Despite this, Soho soon became a flourishing mecca for New York City artists. Amos, Browne, and Stevens and her husband, the artist Rudolf Baranik, were among the first wave of artists to come live and work in this neighborhood as each woman and their respective partners had her own Soho loft by 1968. Billops purchased

a loft in Soho with her husband, the black theatre scholar James V. Hatch, in 1973. She shortly began holding salons there throughout the 1970s, gathering like-minded artists and intellectuals to discuss contemporaneous social, cultural, and political issues. In 1975 Billops and Hatch founded the HatchBillops Archives, an archive of oral histories, photographs, and publications aimed at the promotion and preservation of black culture. In 1981 Billops and Hatch began publishing Artist and Influence, an annual publication which featured interviews between prominent black cultural figures and New York artists. They conducted up to 1,500 interviews with a wide range of artists including Amos and Browne.

The mid-1960s marked a time of strong social involvement for all four women. Each became increasingly involved in the Civil Rights movement and struggle for representation. Amos, the youngest of the four, was also the youngest and only female member of the influential black artist group Spiral, founded by Romare Bearden, Charles Alston, Norman Lewis, and Hale Woodruff. Like many black women activists and artists in the 1960s and beyond, Amos frequently found herself caught between the lack of female leadership in the Civil Rights movement and the lack of diversity in feminist circles, a predicament she became aware of while working at Spiral. Amos famously said:

I thought it was fishy that the group (Spiral) had not asked Vivian Browne, Betty Blayton Taylor, Faith Ringgold, Norma Morgan, or any other woman

of their acquaintance to join. I was probably less threatening to their egos, as I was not yet of much consequence.1

Stevens became involved in the movement in the early 1960s, lending her support as an ally to the struggle for civil rights and the fight against the Vietnam War. In 1963, she exhibited a series of works focusing on the plight of the Freedom Riders. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. signed the preface to her catalogue. She remained a staunch supporter of racial justice throughout her life, a conviction that was guided by her influential friendships with important black artists such as Benny Andrews, Faith Ringgold, and Vivian Browne. Browne was a founding member of the BECC in 1969, having been involved in protesting the lack of black artists included in the Whitney Museum of Art’s The 1930s: Painting and Sculpture in America the previous year. She joined the BECC’s negotiating committee in 1969 and took up its fight to challenge the Whitney Museum’s continued exclusion of black artists from the planning of the 1971 exhibition Contemporary Black Artists in America. In 1972 Browne and Billops became co-directors of the BECC along with Andrews, Clifford R. Johnson, and Russell Thompson.

Though Billops first moved to New York in 1965 and frequently lived abroad throughout her life in New York, she quickly carved a space for herself in the New York art scene, specifically in black activist circles. Browne in particular was critical in helping Billops establish herself in New York City as a young artist, involving her in black rights organizations, feminists spaces, and connecting her to teaching opportunities at Rutgers University; later, Billops was critical in conserving Browne’s memory after she passed away in 1993.

You know, I met Vivian Browne at Huntington Hartford (in Los Angeles, 1964). And then when I came to New York, she invited me into her world, and that’s how I did that. So, it was that group, it was that group.2

The Hatch-Billops archives that she and her husband built and championed constitute a crucial resource in preserving the memory of consequential black artists such as Browne, whose important work and invaluable contributions to activism in the arts has historically been overlooked.

The growing community of feminist artists and activists downtown in the 1970s and 1980s was anchored by only a handful of exhibitions spaces and organizations dedicated to women artists—several of which were founded and promoted by May Stevens. Stevens was the eldest of the four women discussed in this catalogue, and her dedication to the feminist cause generated opportunities for exposure for her peers and successors. In 1973, Stevens helped establish the cooperative gallery SOHO20, and Browne became a member in 1980, serving on the gallery’s board of advisors throughout the rest of her life. Stevens and Browne became close friends in the early 1970s, and Browne likely introduced her to Amos and Billops. Browne and Stevens remained friends for the rest of Browne’s life, travelling to Cuba together with Carl Andre and Ana Mendieta in 1982.

At Browne’s suggestion, Billops connected with Stevens and briefly expanded her own activism to white and multi-racial

feminist spaces in the 1970s and 1980s, including SOHO20 and the Heresies Collective which produced the influential feminist publication Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics. Between its establishment in 1976 and its final publication in 1993, all four women contributed—in varying degrees—to Heresies. Stevens was a co-founder and Amos was a member of the collective from 1982 to 1993. Billops was interviewed in issue #8, Third World Women (1979). Browne and Amos became driving forces behind the publication of issue #15, Racism is the Issue (1982), which examined race and racism within the feminist art movement; Browne and Stevens served on the editorial committee. Stevens has stated:

In the 1970s I became friends with Vivian Browne, who worked with me in the women’s movement and whom I invited to join Heresies. She was very instrumental in seeing that Heresies did an issue on race. We went to Cuba together. We roomed together when we went to Washington, DC, to the College Art Association.3

Browne’s death in 1993 had a strong impact on her friends and peers. Throughout her life, Browne opened doors for herself and held them open for her community. She can be credited with being an important reason why the four women in this exhibition were brought together; following her personal credo:

Don’t knock other women artists. Reach out to others—it’s the only salvation for a crumbling society.4

Amos, Billops, and Stevens as well as the latter two’s respective partners were among the eleven people who spoke at the memorial service that Billops and Hatch organized at the SOHO20 space following Browne’s death. While Browne’s funeral was the last time the four women would be together physically, they were immortalized in Amos’s portrait series, The Gift (1990-1994). Between 1990 and 1994 Amos produced 48 watercolor portraits of dear friends—women artists, activists, and intellectuals as they visited her studio. They were made for Amos’s daughter India as a gift, and are a record of an extraordinary network of women who defined a generation.

Ethel ReniaJune 2021

1. Emma Amos, in Contemporary Feminism: Art Practice, Theory, and Activism? An Intergenerational Perspective, Art Journal 58, no. 4 (Winter 1999)

2. Camille Billops in interview with Shawn Wilson. The HistoryMakers. December 14, 2006

3. May Stevens in May Stevens by Patricia Hills, 2005. p. 37-38

4. Vivian Browne, at a CAA panel, Voices of Art/Voices of Feminism, 1985

1. 1968. Browne gives an interview with Henri Ghent, a prominent curator and BECC activist, for the Archives of American Art Oral History Program at her studio on 77 West 11th Street.

2. 1968. Browne has acquired her loft at 451 West Broadway with the help of her friend Norman Lewis. She was an early member of the Soho Artist Association, which was founded the same year and based in her building. She remained until her death in 1993.

3. 1967. Stevens and Baranik move downtown from Washington Heights to their loft on 97 Wooster Street, where they live for thirty years.

4. 1960s. Amos’s studio is on 1st Avenue and 16th Street until she has her first child in 1967.

5. 1979. Amos acquires a new studio a block away from her home on King Street. The address is 228 West Houston Street.

6. 1969-1990. Amos and her family live at 32 King Street.

7. 1990. Amos moves to a new loft at 21 Bond Street where she both lives and works. This is her last address in New York.

8. 1965. Billops and Hatch come to New York from Egypt and live at 54 East 11th Street before moving to India for several months.

9. 1972-1975. Billops and Hatch return to New York and briefly live at 136 West Broadway.

10. 1975. Billops and Hatch move to their home on 491 Broadway, which they had purchased two years prior. This remained their permanent address for the rest of their lives.

11. 1963-1965. Amos meets with the other Spiral members in their space on 147 Christopher Street. She is the youngest member, and the only woman. Spiral had only one exhibition before losing their exhibition space and dissolving as a group.

12. 1960s-1970s. Bob Blackburn’s Printmaking Workshop is a gathering point for many New York artists, especially artists of color. Amos, Billops and Browne all worked there. Of Blackburn’s Workshop, Amos once said: “Introductions are a major part of the Workshop’s business. Bob makes room for artists. He makes people feel at home at the Workshop.” His address is 55 West 17th Street.

13. 1972. A.I.R. Gallery, one of Soho’s seminal feminist galleries is founded at Stevens’s address on 97 Wooster Street.

14. 1973. Stevens becomes a founding member of SOHO 20. It is initially located at 99 Spring Street.

15. 1976. Heresies’s first headquarters is on the corner of Lafayette Street and Spring Street. Stevens is a founding member; Browne and Amos later become involved in the organization.

16. 1979. The Action Against Racism in the Arts organizes a protest at the Artist House’s extremely controversial Nigger Drawings exhibition. They are formed by members of the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition and Artists and Writers Protest Against the War in Vietnam.

In the 1960s, Soho was an industrial, dilapidated area of New York City, though its cheap prices and expansive spaces proved highly attractive to artists seeking studio spaces and natural light. Soon, Soho became a hub for artists and writers across the cultural spectrum. In 1967, May Stevens moved downtown to Soho with her husband, the artist and activist Rudolf Baranik. She soon became a founding member of two important feminist Soho establishments, SOHO20 and the Heresies collective.

In 1973, Camille Billops and her husband James “Jim” Hatch bought an old dress factory on 491 Broadway and set to the task of converting it into a habitable space and studio. Their home soon became an important neighborhood gathering point for their community of artists and thinkers. By 1965, Emma Amos was making prints at Bob Blackurn’s printmaking workshop and attending Spiral meetings on 147 Christopher Street. She lived at her address on 32 King Street throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Twenty years after her initial arrival in Soho, she interviewed her friend Vivian Browne in the Billops Hatch loft and stated:

You were one of the first artists who lived in Soho and you have a working situation where you live, which many people think is ideal.

Browne acquired her loft on West Broadway in the 1960s at the suggestion of her lifelong friend Norman Lewis. Browne was one of the initial members of the Soho Artist Association, an

association that pushed to change New York City zoning laws to legally allow artists to live and work in Soho loft spaces initially zoned for manufacturing. This group was among the first to popularize the nickname “Soho” to designated the “South of Houston” neighborhood.

Billops and Hatch’s 11th Street loft, 1972. Hatch can be seen at his desk in front; Billops is in the back, working on her ceramics.

“Women are integral to my works. They are people I have known, and I have shared with them a common thread of experience. I love their attitude. They are my solid ground.”

Emma Amos, as quoted in the press release for June Kelly Gallery’s exhibition Emma Amos: Drawing, Etchings and Hand-Woven Canvases, 1981.

During the Civil Rights Era, one had to paint black themes, black people, black ideas. I didn’t. Sometimes that happens now, because there are constantly exhibitions that celebrate that time. I was painting my kind of protest, but it didn’t look like black art. One of the questions we always had when I was teaching then, was whether or not there is a black art. That always came up. It probably always will. Now they’re saying, “Is there a women’s art?” Then, I was painting these little old white men.

Vivian Browne in interview with Emma Amos at the Hatch Billops loft, 1985. This interview was published in Artists and Influence, Volume 4, 1986.

This painting was owned by Camille Billops, and it hung in her home for five decades.

This work was in included in the Attica Book, edited by Benny Andrews and Rudolf Baranik in response to the 1971 Attica prison rebellion.

Not on view in the exhibition

In 1989, Browne established a West Coast studio in Bakersfield, California, and began splitting her time between the East and West Coasts. In California, Browne began painting large sequoias and redwoods, reflecting her growing concern for the environment in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Her largescale paintings of trees juxtapose encroaching powerlines with natural forms.

Founded in 1969, the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition was created in response to the Metropolitan Museum’s controversial exhibition, Harlem on My Mind, which notably omitted black artworks and contributions. Browne was among the first artists to picket the museum, and upon Billops’s return to New York from Egypt in the mid-1960s, Browne, an original member of the organization, invited her to join the fight. In 1972, the two became the only women on the board of directors when the BECC became a non-for-profit. The BECC had previously mobilized to protest the Whitney Museum of Art’s The 1930s: Painting and Sculpture in America in 1968, which also omitted works by black artists.

This Is A Matter of Public Record: a recap of the BECC’s accomplishments, 1971.

Action Against Racism in the Arts flyer, 1979.

In 1972, artist and activist Benny Andrews and the BECC collaborated with Rudolf Baranik’s Artists and Writers Protest against the War in Vietnam to produce the Attica Book, a collection of artworks and poems protesting the brutal death of 43 people during the Attica Prison rebellion the year prior. They included works by Billops, Browne, and Stevens. The trauma of the Attica massacre reverberated among socially-conscious activists in New York and beyond, and the community of artists involved in civil rights and anti-war organizations became occupied with the prisoners’s rights movement throughout the 1970s.

In 1979, the highly controversial Nigger Drawings opened at the Artists Space in New York, prompting swift backlash. The exhibition included charcoal paintings by a white artist anonymously known as ‘Donald’. The BECC—joined by Stevens, critic Lucy Lippard, Rudolf Baranik, James V. Hatch, and more— organized various actions in protest, including a sit-in at the Artists Space and a teach-in at the Hatch-Billops loft.

“When Europe and the East look at this country, they steal our rap and hiphop, our blues, jazz, and country-western, our graffiti, movies, and pop performances, our sneaker-wearing, hard-working women, and our prejudices. Who says the mainstream is blue chip artists? The mainstream is me, baby-darling.

“Why am I so concerned since I am one of those people who seems to be many places at once? Because usually, when you see me, you’ll also see Howardena Pindell, Faith Ringgold, Vivian Browne, Camille Billops, Clarissa Sligh, Deborah Willis, Lorna Simpson ... and the other hardworking black artists who gather in support of each other. But we know that most gatherings of artists, curators, dealers, and critics at museums, galleries, art societies, and socials are without us. DON’T YOU MISS US WHEN WE’RE NOT THERE?”

Emma Amos, Contemporary Views on Racism in the Arts, M/E/A/N/I/N/G Issue #7, 1990.

Amos’s signature investigation into the depictions of the black body frequently took on representations of Josephine Baker. Baker was celebrated for her dancing, and was known for her nudity and provocative costumes with bananas. Here Amos presents the French-American icon, who was politically vocal and one of the most visible black entertainers of her time, with bananas in the background, her body clothed with Amos’s own weaving.

“I did not want to see black women with no clothes on,” Amos said in 1995. “It means something else when a black woman has no clothes on… It means you are for sale.”

Amos was completing a fellowship and residency at The Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Center, Italy, when she learned of Browne’s death. The painting Never, For Vivian is in part a self-portrait, and reflects Amos’s profound grief upon the loss of her friend.

Amos, Billops, and Browne all taught at Rutgers University’s Mason Gross School of The Arts. A lifelong educator, Browne first got hired at the University in 1971 and became the art department’s chair in 1975. She continued working at Rutgers until her death in 1993. Browne was an advocate for the inclusion and promotion of art education in public New York City schools for many years before making the transition to teaching secondary education. When Browne began teaching at Rutgers, she invited several members of her immediate community to join her as members of the art faculty, including members of her co-op on 451 West Broadway, photographer Mary Ellen Andrews, curator Bill Burgess, and Camille Billops, among others.

In 1972, Browne recommended Billops to serve as a lecturer in the department, and Billops spent fourteen years teaching at the school. In 1980, Amos joined the faculty at Rutgers as well, becoming tenured in 1992, and the art department chair in 2005. Both Amos and Browne would spend most of their teaching career at this school, becoming fully tenured professors. In the early 1980s, Browne became bi-coastal and taught at UC Santa Cruz for a number of years.

Though Amos and Browne spent most of their educational careers at Rutgers, Billops and Stevens taught at a variety of institutions, including the City College of New York, School of Visual Arts, New York, and the Skowhegan School for Painting and Sculpture in Maine.

“I have been a teacher for a very long time. And I enjoy teaching very much. … but I did not teach by choice. I did that because I had to live. And at the same time, I had to paint. So, I did both things for a very long time, and as a teacher you go into school and you do what you do, and you do it to the best of your ability. And as an artist you do the same thing. However, as a teacher my principal knew that I was there. As an artist for a very, very long time, nobody knew I was there.”

Vivian Browne, Black Artists in America Panel, 1971, Art Students’ League.

Teaching was an important source of revenue for women artists at this time, and one of the few career paths available to women of color in particular throughout the 1960s and 1970s.

Letter of recommendation for Browne by James Hatch, 1974.

Rudolf was the first white person, maybe the only white person, to be invited by Benny and Cliff to join them in teaching prisoners on Rikers Islands, who tended to be largely black. Rudolf loved telling stories about Camille and her experiences teaching, Camille would bring in things like incense and all kinds of wonderful things to make treats for the prisoners to make their lives more livable and to make prison a less sense-deprived environment for them. She’d have to fight with the guards who didn’t want her to take in anything special. One guard asked, “What’s the incense for?” And she said, “For mood, man.” Camille was unstoppable. May Stevens in May Stevens by Patricia Hills, 2005. p. 32.

All my work is about the celebration of family, my private stories and personal vision. The sculpture Remember Vienna is about me and my husband. The Kaohsiung drawings, which I did in Kaohsiung, Taiwan, are about a magnificent fight that Jim and I had. The two characters are the same as in Remember Vienna, only now they have the Chinese names we both had in Taiwan. I also did a ceramic sculpture and ten drawings called The Story of Mom, which is about my godmother Later, I did a beautiful ceramic vase, fifty-five inches high, about stories of my sister’s childhood.

Camille Billops in interview with George C. Wolfe, ISSUE, A Journal for Artists, 1985.

Amos: Browne:

When you think of your contemporaries, like Ida, Joyce Kozloff, May Stevens, Joan Semel, Elizabeth Murray, Betye Saar, Janet Fish, Faith Ringgold, do you feel your career is like theirs or not?

There are many levels. All those people you mentioned are on different levels for varying reasons. I know some of these people. The ones I don’t know I don’t think about at all. The other people I do know are friends and, in some ways, people whose opinions I respect in terms of what I’m doing. I think I am in a direct line of competition with them. Is that what you’re thinking about?

Amos: Browne:

I was trying to make a list of artists that I thought were more like you without listing male artists. I am surprised you didn’t ask why there weren’t any men on that list.

Because I’m not a man.

Amos:

Browne:

Then what influences have helped you?

May Stevens for instance, has been an influence. Faith Ringgold has been an influence. They influenced me in terms of my making art a career. They pushed. They’ve been very supportive and helpful.

Vivian Browne in interview with Emma Amos at the Hatch Billops loft, 1985 This interview was published in Artists and Influence, Volume 4, 1986.

The monumental painting Artemisia Gentileschi, which celebrates the long-ignored Italian baroque painter Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1656), is emblematic of Stevens’s commitment to challenging patriarchal hegemony and resuscitating forgotten women’s history.

This painting was comissioned to be exhibited in The Sister Chapel, an exhibition conceived in 1974 to serve as a hall of fame for women’s accomplishments. A pun of the famed Sistine Chapel, The Sister Chapter offered a secular, nonhierarchical alternative to the patriarchal system. The exhibition premiered at MoMA PS1 in 1978. A reproduction of Artemisia Gentileschi is permanently on view at Rowan University along with other works originally comissioned for The Sister Chapel.

I did three paintings of Benny Andrews: a portrait of Benny Andrews in profile, with Big Daddy wrapped in a flag behind him, one of Benny and his wife Mary Ellen, and another of Benny with me. They are all about 5 feet square, quite handsome.

A prominent feminist artist, Stevens was a founding member of SOHO20 Gallery in 1973 and the Heresies Collective in 1976. These organizations proved to be valuable gathering points for women artists in the Soho and the wider New York community throughout the 1970s and beyond. In 1980, Browne became involved in SOHO20, quickly joining the gallery board of advisors, on which she remained for the rest of her life. In 1981, she encouraged Billops to join the gallery, and the two became active in the “Alternate Gallery Programs” Committee, though Billops’s frequent travel and relative skepticism of a white feminist action group interrupted her sustained membership to this organization. In 1984, Amos also participated in a group exhibition at the feminist gallery.

In 1977, the Heresies Collective began publishing HERESIES: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics. In 1982, Stevens invited her friend Browne to serve on the editorial committee for the publication’s important issue discussing racism in the art world and wider society. Together, they invited Amos to contribute. Amos became a member of Heresies from 1982 until the collective dissolved in 1993. Though Billops refused to contribute to this particular issue, she and Browne both contributed to Heresies’s earlier 1979 issue, Third World Women: The Politics of Being Other, and both women spoke at the accompanying panel at the SOHO20 space.

Amos and Stevens—respectively the youngest and eldest women of this quartet—both went on to become original Guerilla Girls when the infamous feminist group was formed in 1985.

Printmaking was an important part of Amos and Billops’s art practices. Along with Browne, the two made many prints at Bob Blackburn’s Printmaking Workshop, which served as an important community gathering place for artists of color in New York and beyond. Stevens made very few prints throughout her career. Most of the prints produced by these artists were selfpublished.

Earlier, I think the Civil Rights movement made me more critical about what I was doing. I could not in good conscience paint just lovely colored pictures with brushy strokes without having some of the pain and angst of the things that I wanted to say about women, black women in particular, in the sixties. I did that, but without anybody telling me what to do or anybody looking at the work, or any of the men responding to it in any way. The work was never shown.

To Sit (With Pochoir), 1981

Etching, aquatint and styrene stencil

29 1/2 x 40 inches (74.9 x 101.6 cm)

The four portraits included in this catalogue are that of May Stevens, Vivian Browne, Camille Billops, and Emma Amos. These are only four of the original forty-eight portaits that constitute The Gift.

26 x 19 3/4 inches (66 x 50.2 cm)

26 x 19 3/4 inches (66 x 50.2 cm)

Represented in this work from left to right:

Zora Neale Hurston, Kay Walkingstick, Emma Holmes Amos; India De Laine Amos, Fisk Athelete, Paul Robeson, Jack Johnson, Jim Thorpe, May Stevens; Veoria Warmsley Shivery.

I went to Bob Blackburn’s and stepped into that world, Bob Blackburn and the printmaking world, and met all these fabulous people.

Krishna Reddy, and Bob Blackburn, and Mohammed Khalil, Vincent Smith. Bob got some money for black artists. You know, at that time they were giving all that funding. And although Bob complained that the black people were making too much noise. We are noisy, we tend to be noisy. And Bob, you know, was used to riding the other little ledge. And we were noisy, because he was a senior, you know. All of us, Mel Edwards was in that group, and Vincent Smith was in that group, and Vivian Browne. I don’t know if Emma was, but she was over there. I just met all these other people. I kept getting this wave of fabulous people to meet, you know, that would enrich me, would help me with my work. And I was evolving, and I’m forever grateful for everybody I ever met.

Benny had the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, and Benny invited me to be in shows. The rest of them didn’t know me or care or whatever. But Benny invited me to be in shows. And he did this famous exhibition called ‘Blacks: USA’ (Blacks: USA: 1973) which was at the old Huntington Hartford museum (Huntington Hartford Gallery of Modern Art; Museum of Arts and Design) in Columbus Circle. And I was, by that time, starting shooting. I started shooting openings, I started photographing openings. And I shot that show in—oh, man, ‘73. And there is Benny and Alverine, and we were young.

Camille Billops in interview with Shawn Wilson. The HistoryMakers. December 14, 2006.

For Japanese with Mirrors, 1975

Etching and aquatint, relief printed

26 x 19 1/2 inches (66 x 49.5 cm)

Among fantastic foliage, nonsensical writing, and whimsical creatures, a nude black woman lounges in an imaginary landscape. She is an odalisque, black and sexually available. She is a black Venus whose posture channels the Western traditions of reclining nudes by Rubens, Titian, and Manet. She is a Jezebel, deceptively submissive and dangerously erotic. Camille Billops’s character performs a matrix of mythic identities ascribed to women in the 1974 etching I am Black, I am Black, I am Dangerously Black. With typical tongue-incheek humor, Billops, a New York artist and filmmaker, used satire and whimsy to reject simplified notions of blackness and question the social and sexual expectations of black women.

Adrienne Childs, Activism and the Shaping of Black Identities (1964-1988), in The Image of the Black in Western Art, 2014.

Billops

I am Black, I am Black, I am Dangerously Black, 1973 Etching and aquatint with chine collé 22 x 30 inches (55.9 x 76.2 cm)

In Mammy’s Little Coal Black Rose (1992), part of her Minstrel Series, Billops combines caricatured images of white entertainers in black face with lines of music featuring racially demeaning song lyrics. Billops’s art does more than merely unmask the tradition of a minority group mimicked for amusement by a racial majority. As the artist has stated, the pieces invite the viewer “to peek behind the minstrel mask and speculate who was hiding there ... and why.

Billops’s Figherfighter prints, which vary in printmaking technique and color, accompany her large ceramic Story of Mom, made nine years prior.

Etching and aquatint with chine collé 15 x 22 inches (38 x 55.9 cm)

In 1982, Billops began her filmmaking career with Suzanne, Suzanne, and subsequently made Finding Christa in 1991, an autobiographical work that garnered the Grand Jury Prize for documentaries at the 1992 Sundance Film Festival. Her other film credits include Older Women and Love in 1987, The KKK Boutique Ain’t Just Rednecks in 1994, Take Your Bags in 1998, and A String of Pearls in 2002. Billops produced all of her films with her husband and their film company, Mom and Pop Productions.

The print The KKK Boutique served as a design for the film’s poster. The film takes on every day casual racism that manifests itself across the cultural spectrum.

What kind of socialist-feminist-artist am I?

What kind of socialist artist loves Corot as well as Courbet and forgives oil painting its bourgeois origins and abstract expressionism its heraldry of U.S. imperialism?

What kind of feminist artist sees pink as a private color to be sparingly used?

To the women’s movement I would like to bring, as to art, the subtlest perceptions. To political action, I would like to bring, as to art, a precise and delicate imagination.

The personal is the political only if you make it so. The connections have to be drawn. Feminism without socialism can create only utopian pockets. And the lifespan of a collective is approximately two years.

Socialism without feminism is still patriarchy. But more smug. Try to imagine a classless society run by men.

Trying to be part of collective is a little like being a chameleon set on plaid. I may split apart before I get the pattern right. But somehow it seems worth the pain because I believed community is the highest goal.

I believe every woman’s life is a little better because of what we are doing.

In 1967, Stevens began painting her “Big Daddy” figure—a smug, fleshy, bald and bespectacled middle-aged figure, often naked and accompanied by a bulldog, loosely based on an image of her father. Born out of Stevens’s passionate involvement in both the antiwar and feminist movements, Big Daddy was to Stevens, “…a relative of mine who represented to me an authoritarian and closed attitude towards the world. It was a middle-American attitude towards culture, towards politics, towards black people, and towards Jews. He was a person who stopped thinking when he was twenty and hadn’t opened his mind to anything since.”

Not on view in the exhibition

This work was in included in the Attica Book, edited by Benny Andrews and Rudolf Baranik in response to the 1971 Attica prison rebellion.

Two Women consists of a top band of images of Rosa Luxemburg—as a child of twelve, as a young woman of forty, as the bloated corpse that floated to the surface of the Landwehr Canal in March 1919—and a bottom band of snapshots of Alice Stevens—as a child with her two siblings, as a young matron holding her first born, and as an elderly nursing home inmate. The vertical pairing expresses the differences: whereas Luxemburg is shown alone, Alice is surrounded by family and home. Captions also tell of differences: whereas typewritten texts for Luxemburg suggest authorities publicly substantiating the identifications, Stevens’s own scripted text for her mother indicates the private nature of her own memories.

May Stevens by Patricia Hills, 2005. p. 73.

This work appeared in the first issue of Heresies.

May Stevens

Two Women, 1976

Collage with photostat, ink, and photographs 10 1/4 x 13 1/2 inches (26 x 34.3 cm)

In the Hatch-Billops collection.

11 3/8 x 20 1/2 inches (28.9 x 52.1 cm)

May Stevens

after “Green Field”, 1990

As far as the black woman artist is concerned, she has for a number of years—for many, many years—had to depend on the black male artist to get shown, to get known, to get around and really to get the exposure that’s needed.

Browne, at the Black Artists in America Panel, 1971, Art Students’ League.

Browne learned about the 1839 Amistad slave ship mutiny during the late 1960s, when she became involved in black rights issues. Using etching, a medium she perfected at Robert Blackburn’s Workshop, Browne brought forward her subject using random markings on the plate. According to curator Deborah Wye, “the result is a symbolic statement on freedom and slavery. She interprets the image on the right as a gesture of flight and escape, and that on the left as a suggestion of cotton bales and burlap, which evokes the lives of those left behind.”

The three etchings by Browne in this catalogue were printed at Bob Blackburn’s Workshop.

Browne’s death in 1993 had a profound impact on her community and friends. Amos paints a portrait of Browne as she is dying of cancer. Stevens’s husband Rudolf Baranik makes a collage in her memory. Billops and Hatch organize a memorial service at the SOHO20 space, and he composes a poem for her. Stevens writes Browne’s obituary for the Village Voice and flies to California to speak at her memorial exhibition at California State University. Browne had become bi-coastal in the last decade or so of her life, maintaing her loft on West Broadway and sharing a home in California with her partner, the artist Vida Hackman. Though Amos, Billops, and Stevens remained friends, colleagues, and peers for the remainder of their respective lives, Browne’s impact on their careers and friendships was immeasurable, and her death marked the last time the four were brought together in a social and artistic fashion.

1963-65

1964

Amos is a member of the influential artist group Spiral. They meet weekly at Christopher Street Gallery to discuss the role of African-American artists in politics and the civil rights movement, as well as in the larger art world. Amos is the youngest and only woman member of the group.

Billops and Browne meet as fellows at the Huntington Hartford Foundation in Los Angeles.

Amos is at Bob Blackburn’s Workshop, perfecting her printmaking. Amos would later reflect on her time at Blackburn’s workshop as a young mother in the 1970s:

Managing a toddler and a nursing infant is a full-time job, but it leaves plenty of time for boredom and a feeling of isolation. … Always a printmaker, my sanity was saved by Bob Blackburn’s insistence that I come to the Printmaking Workshop as often as I could afford to leave the children with my husband or a sitter. In hindsight the work was not groundbreaking, but making prints was a way to continue being an artist.

1968 1971

Browne and Billops protest the Whitney Museum of American Art’s exclusion of black artists from an exhibition, The 1930s: Painting and Sculpture in America. In 1969, black activists organized to form the Black Emergency Coalition for Culture in response to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Harlem on My Mind. Browne is an original member of this organization.

Browne begins teaching at Rutgers University, following student protests denouncing the lack of black representation at the University in the late 1960s.

Browne recommends Billops to start working as a lecturer at Rutgers’s Art Department.

Rudolf Baranik and Benny Andrews edit Attica Book: By the BECC and the Artists and Writers Protest Against the War in Vietnam. They include works by Browne, Stevens and Billops.

The BECC is incorporated as a not-for-profit organization. The initial directors of this newly incorporated organization are Clifford R. Joseph, Benny Andrews, Camille Billops, Vivian Browne and Russell Thompson.

Inside cover of the Attica Book, 1972.

Stevens becomes a founding member of SOHO20.

Billops starts making prints at Bob Blackburn’s Workshop, joining Browne and Amos.

Billops’s hand-written note describing her first experience at Bob Blackburn’s Workshop.

Billops and Browne participate in Synthesis, the inaugural exhibition of the historic Just Above Midtown Gallery.

Stevens is a founding member of the Heresies Collective.

Baranik, Billops, Browne, Stevens and Lucy Lippard picket the Whitney in protest of their Three Centuries of American Art, which they deem upholds a biased representation of American art history.

The Heresies Collective Women. Image via joanbraderman.com

Billops and Hatch found the Hatch-Billops archives, a collection of thousands of books and other printed materials, more than 1,200 interviews, and scripts of nearly 1,000 plays.

Heresies publishes its first issue Feminism, Art and Politics.

Heresies: A Feminist Publication on Art and Politics publishes its 8th issue, Third World Women. Browne, Stevens and Billops each participate.

Rudolf Baranik, Billops, Browne, James Hatch, and Stevens, among others, protest Artists Space’s highly controversial Nigger Drawings exhibition featuring works by a white artist.

Amos starts teaching at Rutgers University.

Billops and Hatch begin publishing Artist and Influence, an annual publication which featured interviews between prominent black cultural figures and artists. They conduct interview of Amos and Browne, among many others.

Herbert Gentry, Norman Lewis, and Vivian Browne at Jacob Lawrence’s party. All four people mentioned are interviewed by Billops and Hatch for their oral history project.

Billops joins Browne and Stevens as a member of SOHO20. She and Browne become members of the “Alternate Gallery Programs” Comittee.

Browne, Stevens and Baranik go on an influential trip to Cuba with friends Ana Mendieta, Carl Andre, Irene Wheeler, and Robert Edwards, among others.

Mendieta with May Stevens, circa 1980.

Heresies publishes its 15th issue, titled Racism is the Issue. This is co-edited by Browne and Stevens. They invite Amos to participate.

Backcover of Heresies’s 15th issue.

Billops, Browne and Hatch travel to China together.

Billops and Browne in China, 1983.

The Guerilla Girls group is founded. Amos and Stevens count as two of the original activists to form this historic coalition of feminist artists.

Heresies publishes its 27th and final issue, LATINA – A Journal of Ideas.

Invitation to a Heresies Meeting at Amos’s studio on West Houston for the final edition of Heresies.

Browne dies after less than a year’s fight with cancer. Amos, Baranik, Billops, Hatch, and Stevens all speak at a Hatch-led memorial at the SOHO20 space.

1965

1971

1973

1974

Festival of Arts, Temple Emanu-El, Yonkers, NY. Included Amos, Browne, the Spiral members, and more.

Women in Art, panel and video produced by Bonnie Bellow, Pacifica. Included Billops, Stevens, and Lucy Lippard.

BLACKS:USA:1973, New York Cultural Center, New York. Curated by Benny Andrews. Included Billops and Browne.

Synthesis: A combination of parts or elements into a complex whole, Just Above Midtown, inaugural exhibition.

Included Billops and Browne.

Artists’ Benefit Sale For Encounter Inc., New York. Included Billops, Browne and Stevens. Rutgers University Studio Art Faculty-Camden-Newark, 1974-75, University Art Gallery, Vorhees Hall, Rutgers, The State University of NJ. Included Billops and Browne.

Black Artists in the New York Scene, Acts of Art, Inc. Included Billops and Browne.

Chile Emergency Exhibition, U.S. Comittee for Justice to Latin American Political Prisoners. Included Baranik and Billops.

1975 A Black Perspective in Art, Black Enterprise Magazine, New York. Included Billops and Browne.

1976

Inaugural exhibition celebrating the founding of the firm Clark, Phipps, Clark & Harris Inc., New York. Included Billops and Browne.

1978 Third-World Women Artists. SOHO20 Gallery. Included Billops, Browne and Stevens. Women Artists ‘78, Women’s Caucus for Art (WCA), City University of New York. Included Browne and Stevens. Twenty Contemporary Printmakers, Pennsylvania State University. Included Amos, Browne, and Billops.

1979 Impact 79: Afro-American Women Artists, Florida A&M University Foster-Tanner Fine Arts Gallery. Included Billops and Browne.

1980 Art for Zimbabwe, Just Above Midtown Gallery. Included Baranik, Browne, Billops, and Stevens. Fragments of Myself/ The Women, Douglass College Art Gallery, New Brunswick, NJ. Curated by Joan Marter. Included Amos and Browne.

Black American and Third World Artists, Yolisa House Gallery, New York. Included Amos, Billops, and Browne. Artists Who Make Prints. Lowenstein Library Gallery, Fordham University at Lincoln Center. Curated by Berenice

D’Vorzon. Included Amos and Browne.

1981 Artists Invite Artists, New Museum, New York, organized among others by Baranik and Billops. Included Browne. Recent Directions, Rutgers-Newark Art Department and New Jersey School of Architecture Faculty. Included Billops and Browne.

Forever Free : Art by African-American Women, 1862-1980, University of Maryland Art Gallery. Curated by David Driskell. Included Billops and Browne.

Voices Expressing What Is, Action against Racism in the Arts, Westbeth Gallery, New York. Included Baranik, Billops,

and Stevens.

Installations in The Five Elements, Kenkeleba House, New York. Curated by Camille Billops. Included Amos, Billops, and Browne.

1982 The Wild Art Show, MoMA PS1, curated by Faith Ringgold. Included Amos, Billops, and Browne.

Twenty-five Approaches to Contemporary Printmaking, Paul Robeson Cultural Center, Pennsylvania State University, Philadelphia. Included Amos, Benny Andrews, Billops, and Browne.

Recent Acquisitions of the Schomburg Collection, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York. Included Amos and Browne.

Artists New York/Taiwan; Spring Gallery/AI IN TAIWAN. Included Billops and Browne.

1983 Jus’Jass: Correlations of Painting and Afro-American Classical Music, Kenkeleba Gallery, New York. Included Amos, Billops and Browne.

Exchange of Sources-Expanding Powers, Cal State Stanislaus Art Gallery. Included Browne and Stevens.

Printed by Women: A National Exhibition of Photographs and Prints, Philadelphia: The Port of History Museum at Penn’s Landing. Included Amos, Billops, and Stevens.

Reconstruction Project, Artists Space, New York. Included Amos and Billops.

1984 Hanging Loose, Port Authority Bus Terminal, organized by The Organization of Independent Artists, curated by Emma Amos and Judy Negron. Included Amos and Browne.

1984 Art Against Apartheid, Louis Abrons Arts for Living Center, New York. Sponsored by the Fountdation for the Community of Artists, with the support of the United Nations Special Committee Against Apartheid. Curated by Willie Birch. Included Baranik, Browne, and Stevens.

Celebration: Eight Afro-American Artists selected by Romare Bearden, Henry St. Settlement, Louis Abrons Arts for Living Center, New York. Included Amos and Browne.

Art in Print: A Tribute to Robert Blackburn, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Included Amos, Billops, and Browne.

Affirmations of Life, Kenkeleba Gallery, New York. Included Amos and Billops.

Focus on Black Artists, Rockland Center for the Arts. Included Billops and Browne.

1985

Tradition and Conflict, Images of a Turbulent Decade 1963-1973, Studio Museum in Harlem. Curated by Dr. Mary Schmidt Campbell. Included Amos, Baranik, Billops, Browne, and Stevens.

American Women in Art: Works on Paper and an American Album, United Nations Conference on Women, Nairobi, Kenya. Included Browne and Stevens.

Reflections: Women In Their Own Image, Autobiographical Works by Women Artists, Ceres Gallery. Included Billops and Browne.

Images of Jazz, Wilson Arts Center, Rochester, NY. Included Amos and Billops.

Black Women Artists at Mid-Career, First Women’s Bank. Included Amos, Billops, and Browne.

Generations in Transition: An Exhibit of Changing Perspectives in Recent Art and Art Criticism by Black Americans,

1970-1984 Hampton University. Included Amos and Billops.

Through a Master Printer: Robert Blackburn and the Printmaking Workshop, Columbia Museum, Columbia, SC.

Curated by Nina Parris. Traveled to Arkansas Art Center, Little Rock, and Mississippi Museum of Art, Jackson, MS. Included Amos, Billops, and Browne.

1986 Artists Support Black Liberation, a benefit for the Malcom X Centers for Black Survival. La galeria en al bohio, New York. Included Baranik and Browne.

Prints by Women, Associated American Artists, New York. Curated by Susan Teller. Included Amos, Browne, and Stevens

The Heroic Female: Images of Power, Ceres Gallery, New York. Curated by Nancy Azara. Included Browne and Stevens.

1986 In Homage to Ana Mendieta, Zeus-Trabia, New York. Included Browne and Stevens.

Masters and Pupils: The Education of the Black Artist in New York: 1900 - 1980, Jamaica Arts Center and Metropolitan Life Gallery. Included Amos and Billops.

Choosing : An Exhibit of Changing Perspectives in Modern Art and Art Criticism by Black Americans, 1925-1985, Hampton University, New York. Curated by Jacqueline Fonvielle-Bontemps. Included Billops and Browne.

1987 Heresies Issues That Won’t Go Away, 100 +, PPOW Gallery, New York. Included Amos, Browne, and Stevens.

Forward View, Gallery at Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Princeton, NJ. Included Amos, Billops, and Browne.

HOME, 23rd annual art show, Goddard-Riverside Community Center. Curated by Faith Ringgold. Included Amos and Browne.

100 Women’s Drawings, Hillwood Art Gallery, Long Island University, New York. Included Amos, Billops, and Browne. Connections Project/Conexus: A Collaborative Exhibition Between 32 Women Artists from Brazil & the United States, Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art, New York. Included Amos, Browne, Stevens. The Afro-American Artist in the Age of Cultural Pluralism, Montclair Museum of Art, Montclair, NJ. Included Amos and Billops.

7 Urban Artists: Diverse Expressions in Multiple Media, Firehouse Gallery, Nassau Community College, New York.

Included Amos and Billops.

1988 Committed To Print : Social and Political Themes In Recent American Printed Art, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Included Amos, Baranik, Browne and Stevens.

Work of The Spirit, Works by Women Artists, Ceres Gallery. Included Browne and Stevens. Coast to Coast, A Women of Color National Artists’ Book Project, Jamaica Art Center, Jamaica, NY. Curated by Faith Ringgold. Included Amos and Browne.

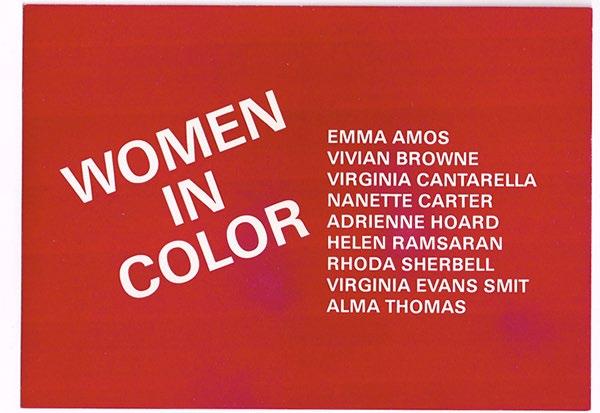

1989 Women in Color, Manhattan East Gallery, New York. Included Amos and Browne. Lines of Vision-Drawings by contemporary women, Hillwood Art Gallery & Blum-Helman Gallery, New York. Curated by Judy Collischan van Wagner. Included Amos, Billops, Browne and Stevens.

Running Out of Time: 9 Women Artists Take a Planetary Turn to the 90s, onetwentyeight gallery, New York. Included Browne and Stevens.

Autobiography: In Her Own Image. Curated by Howardena Pindell, INTAR Latin American Gallery and Women &

Their Work. Included Amos, Browne, and Billops.

American Resources: Selected Works of African American Artists, Bernice Steinbaum Gallery, New York. Included Amos, Billops, and Browne.

1990 Black Women in the Arts, Montclair State College Gallery, New Jersey. Included Amos and Billops. c. 1990 Women Artists of the 90s, Wendell Street Gallery, Cambridge, MA. Included Amos, Billops, Browne and Elizabeth Catlett.

1991 Progressions: Cultural Legacy, The Clocktower, New York. Curated by Julia Hotten, Browne and Amos. Included Billops.

1992 The expanding circle: A selection of African American Art, Gallery at Bristol-Myers Squibb, New Jersey Included Amos and Browne.

Bob Blackburn’s printmaking workshop artists of color, Long Island University, travelled to the Bronx River Art Center and Gallery. Curated by Noah Jemison. Included Billops, Browne, and Stevens.

1995 A Larger Reality, Adobe Krow Archives and The Late Work, Todd Madigan Gallery, California State University, Bakersfield, CA. Memorial exhibition for Browne. Stevens gave the opening remarks.

1996 A Woman’s Place, Monmouth Museum, New Jersey A Woman’s Place, Monmouth Museum, New Jersey. Amos showed her painting Never, For Vivian.

This catalogue is published on the occasion of the exhibition, Friends and Agitators : Emma Amos, Camille Billops, Vivian Browne and May Stevens 1965-1993, June 4 – August 13, 2021, at RYAN LEE Gallery in New York.

© Copyright RYAN LEE Gallery 2021

All rights are reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior written permission of RYAN LEE Gallery.

Editor: Ethel Renia

Essay, research, and text: Ethel Renia

Catalogue design: Mikhail Mishin, Ethel Renia

Photography of artwork: Amir Badawi, Mikhail Mishin, Adam Reich

Publisher: RYAN LEE Gallery, available on ISSUU.com

All archival images courtesy of the Hatch Billops Collection, New York and the Adobe Krow Archives, Los Angeles.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021912408

Camille Billops at Synthesis, the inaugural exhibition of Just Above Midtown, 1974.

Camille Billops at Synthesis, the inaugural exhibition of Just Above Midtown, 1974.