Architecture, Design and Legacy

Architecture, Design and Legacy

PART I

Architecture, Construction and Design

House

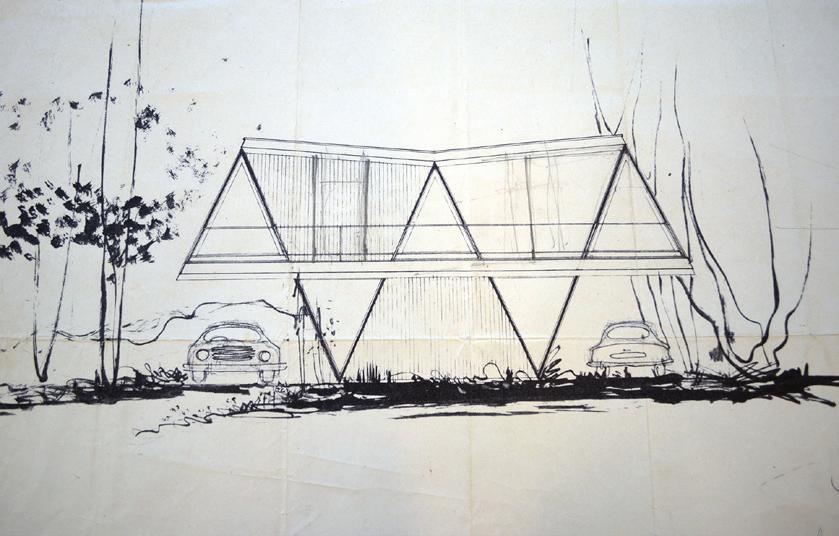

In 1955 Melbourne architect David Chancellor designed the McCraith House—otherwise known as ‘Larrakeyeah’—for his clients Gerald and Ellen (Nell) McCraith. The small beach house, sited overlooking Safety Beach at Dromana, was a bold experiment in suspension, structure and geometry. Seemingly poised on the points of two giant triangles, it became known as the ‘Butterfly House’ and is now an icon of Melbourne’s 1950s avant-garde architecture. The McCraith House gained prominence from the beginning: through publication, heritage citation and exhibitions. It was the focus of the Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery exhibition The House on the Hill (2006), curated by Rodney James; and was also included in the 2014 travelling exhibition Iconic Australian Houses, curated by Karen McCartney— ensuring national recognition for this prototypal Australian beach house.

Nineteen fifty-five was a seminal year for the architectural firm Chancellor and Patrick, with burgeoning commissioning where their desire to experiment flourished. During his university years, Chancellor was influenced by Melbourne architects Roy Grounds and Ray Berg, especially Grounds’ ‘will to experiment’. This experimentation also needs to be seen in the context of overseas and Australian avant-garde architecture. In Melbourne, during the postwar period there was a growing exploration of suspension; shape and geometry through plan and form; structure; open planning for an indoor-outdoor lifestyle; and new technology and materials. The interest in suspension arose from a local and international avant-garde interest in Konrad Wachsmann space-frame design.1

‘A bold experiment in suspension, structure and geometry. Seemingly poised on the points of two giant triangles, it became known as the “Butterfly House”’

WINSOME CALLISTER

Previous page View of McCraith House from Caldwell Road, 2013, architect David Chancellor

Chancellor and Patrick were at the hub of Melbourne’s avant-garde architecture and ideas in the mid-1950s. Their office was based in Frankston but during 1955 and 1956 Chancellor also taught at the University of Melbourne and in 1955 served as a judge for the Herald Ideal Small Homes Competition, alongside Professor Brian Lewis and Robin Boyd. 2 David Chancellor and Rex Patrick submitted an entry in the 1952 Olympic Swimming and Diving Stadium Competition for the 1956 Melbourne Olympic Games and, though unsuccessful, they would have known the winning design by architects Kevin Borland, John and Phyllis Murphy and Peter McIntyre, with engineer Bill Irwin. The tensile structure created great interest in Melbourne and was seen as a symbol of post-war modernity and progress. 3

Overseas influences played an important role in the development of Chancellor’s modernist vision. Chancellor cites his interest in the work of American architect Paul Rudolph, in particular Rudolph’s tensile structures such as his small Healy Guest House (1950), Sarasota, Florida. At the time Chancellor designed the McCraith House, he was shifting away from his earlier interest in Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and, together with Patrick, was looking to Frank Lloyd Wright, following Wright’s publication of The Natural House (1954). As architectural historian Henry Russell Hitchcock pointed out, the post-war climate enabled Wright to explore a ‘range of geometrical and structural themes’.4 Wright’s philosophies aligned with a number of central interests of the Melbourne mid-century avant-garde. This included the primacy of the site, experiment with geometry and structure, new technology and an individual approach to each design. The work of American emigré architect Richard Neutra was also an ongoing influence for Chancellor. Neutra’s use of structure in the interrelationship of building and landscape was of particular interest. Both Wright and Neutra focused on designing for the primacy of the lived experience. Similarly, in his 1956 lecture ‘The Art of Space’, Grounds called for the alliance of architect and engineer and stressed the primacy of the space within. 5 It is clear the McCraith House identified with these design approaches.

2 david chancellor taught Building construction 1&2 and 5th year design in 1955 and 1956. his architecture practice workload made it impossible to continue. david chancellor, correspondence with the author, 20 december 2000.

3 A structure stabilised by tension rather than compression.

4 henry-russell hitchcock, ‘wright’ in Encyclopedia of Modern Architecture, gen. ed. gerd hatje, the world of Art Library (London: thames & hudson, 1963), 320–5.

5 roy grounds, ‘the Art of space: Lecture’ (1956), Architectural science extension course, university of sydney, in Architectural science, ed. prof. henry J cowan, no. 2 (sydney: sydney university extension Board, 1957), 163–7.

Opposite Healy Guest House, Cocoon House, Siesta Key, Florida, site plan and elevation 1950, architect Paul Rudolph

‘Wright’s

philosophies aligned with a number of central interests of the Melbourne mid-century avantgarde. This included the primacy of the site, experiment with geometry and structure, new technology and an individual approach to each design.’

The McCraith House reflected a significant cultural change in post-war Australia. After the privations of the war years and ongoing coupon rationing, the 1950s ushered in an optimistic decade that embraced the notion of progress related towards a new urban lifestyle that included planning for leisure. The growth of the architect-designed house by the coast or in the bush exemplified this urban focus and, as it became more affordable, was preferred to the shacks and camping that had dominated previous decades. There was a sense of glamour linked to Australia’s alliance with America in the final years of the war, and the subsequent adoption of aspects of the American lifestyle. From the early 1950s architect-designed beach houses that embraced this cultural change dotted the shoreline and coastal bush of Port Phillip Bay. These included Roy Grounds’ Henty House (1953), Frankston; Mockridge Stahle & Mitchell’s Ross House (1953), Sorrento, and Johnson House (1955), Beaumaris; Robin Boyd’s ‘Pelican’ Myer House (1956–57), Mt Eliza; and Rae Featherstone’s ‘Blue Peter’ Raymond House (1956), Frankston. Reviews of architect-designed beach houses were published in architectural journals, newspapers, and popular publications like Australian Home Beautiful, encouraging the desire to live or spend weekends on the coast. Chancellor’s architecture was included in this recognition. His Wallace Mitchell House (1953), Mt Martha (now demolished) was reviewed by Robin Boyd for the Herald and also appeared in an Australian Home Beautiful review that focused on leisure.6 The Homemaker image of the McCraith House, published soon after completion, was of a view from the interior, which captured the triangular theme, the steel pipe frame thrusting up through the kitchen, modern deck chairs on the balcony, and Safety Beach in the distance below. It was image as ideal in terms of the lived experience.

6 on reading Boyd’s Herald review, e m henderson drove to Frankston and commissioned chancellor to design a beach house for him, to be sited on the dunes at Queenscliff, overlooking the rip. the henderson house burnt down.

Bottom Interior view of McCraith House, Homemaker magazine May, 1956

Opposite Interior view of McCraith House, Homemaker magazine May, 1956

Chancellor drew the initial design for the McCraith House in the sand at Torquay, during a brief stay while supervising the Henderson House at Queenscliff. The scheme was highly experimental. Chancellor even suggested to his client that it may be too experimental; however, this was exactly what Gerald McCraith wanted. From there, the design and development process moved to completion without

Working drawings for house at Dromana for G. McCraith, February 1955, architect David Chancellor

change.7 Colin Jones and Charles Duncan did the Working Drawings.8 Chancellor covered the engineering, and his designs were approved by renowned structural engineer Frank Dixon. Before his service in the navy, Chancellor had worked for the engineering firm Johns and Waygood and studied engineering at the Royal Melbourne Technical College, altering his course after the war to study architecture. Owner Gerald McCraith took over the building process with the builder Max K Howell.9

On a steep hillside site overlooking Port Phillip Bay, the steel frame timber house offered spectacular views of land, sea and sky. The main floor, rectangular in plan, included an open plan living and kitchen area, a bedroom and small bathroom. The ground level core comprised two small rooms: a laundry-bathroom and bunk bedroom. Chancellor employed this planning in the Henderson and Shanasy houses designed the previous year—the first raised houses that began a strong direction in Chancellor and Patrick design.10 The ground-level utility core, comprising a combined laundry-bathroom and often a storeroom, continued as a strong planning element in Chancellor and Patrick’s raised houses, particularly the beach houses, where the first-floor level was often cantilevered out over the core.

7 david chancellor has often recalled this over the years, as did gerald mccraith when i met him at ‘Larrrakeyeah’ during an mprg tour of the building, 12 september 2006. the only small change to the sketch plan, as the working drawing shows, is the reversal of the bedroom bathroom position in the firstfloor plan. house at dromana for gerald mccraith esq., sketch plan, ground Floor & First Floor, dc, Feb ’55, 86.1, and working drawing cd, march ’55, 86.8, rmit design Archives.

8 colin Jones joined the office of david chancellor, Architect, in Frankston, at the beginning of 1954 after graduating from the Atelier at the university of melbourne. the partnership of chancellor and patrick was formed on 7 June 1954. Jones became a core member of the firm, continuing under rex patrick after david chancellor retired in 1981. Architecture students charles duncan and david nall commenced work with chancellor and patrick in 1955.

9 invoice from dromana timber & Builders supplies pty Ltd to max k howell, 30 may 1955, rmit design Archives.

10 For further discussion and illustrations of the henderson and shanasy houses see winsome callister, Anchoring Identity: the Architecture of Chancellor and Patrick, 1950–1970, vols i & ii (phd thesis, monash university, 2008), bridges.monash.edu.

Plan of ground and first floor of the house at Dromana for G. McCraith, February 1955, architect David Chancellor

Shanasy House, Beleura Hill Road, Mornington Peninsula, 1954, architect David Chancellor

Shanasy House, Beleura Hill Road, Mornington Peninsula, 1954, architect David Chancellor

Timber frame of McCraith House, 1955

Timber frame of McCraith House, 1955

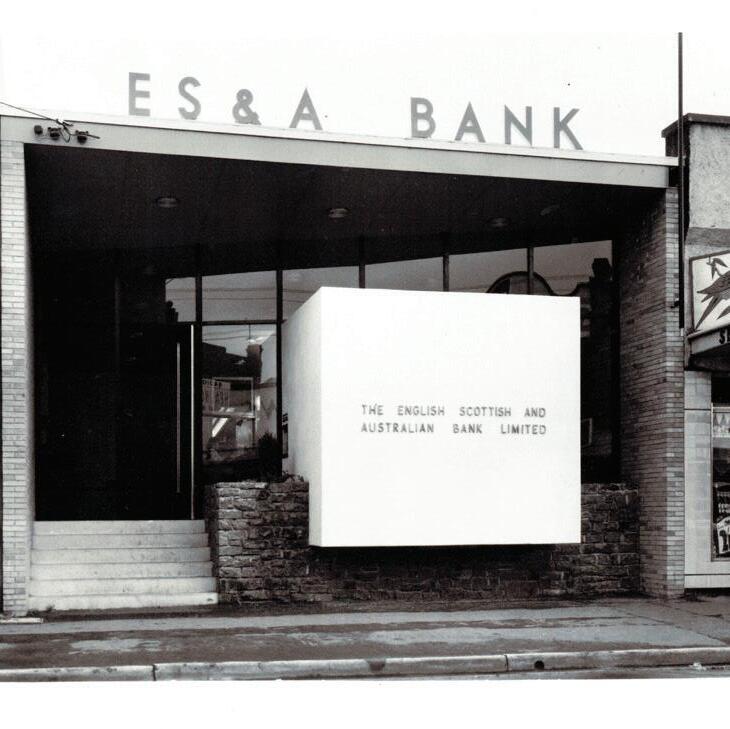

The McCraith House was an experiment in cantilevering.11 With its sloping lapped timber walls and butterfly roof, the raised house form was cantilevered over the ground level core on all four elevations. This provided car spaces on either side, a full width balcony and butterfly awning on the facade, and the first-floor kitchen and stair entry at the rear of the house. The stairs were hung by thin vertical iron rails from the first floor. The house form was suspended on a triangular steel pipe framework, with the triangular theme continued in the windows on the north facade and the balcony structure. Even the water tank behind the house was raised on a tripod from a triangular shed. Several later well-known Chancellor and Patrick buildings, such as the ES&A Bank, Elizabeth Street (1958), Melbourne, and Freiberg House (1958), Kew, were prefigured in their experimental work of the mid-1950s. In his bold design for the small single storey ES&A Bank Branch (1955), Cheltenham (now demolished), Patrick set the concrete strongroom at the front of the bank, thrusting it through the glass facade and suspending it over the pavement. This prefigured Chancellor and Patrick’s raised, flatroofed houses, such as the Burgess House (1957), Beaumaris, where the timber house form was cantilevered out over four brick piers in the cruciform plan. The raised prow house form, like the Freiberg House, had its beginnings in the Crosby House (1956), Mornington (now demolished). The post and beam structure was clearly articulated, with the balcony cantilevered beyond the living area in the T-shaped plan. Some of Chancellor and Patrick’s geometric schemes that were put forward from 1954 remained projects. However, the houses that did go ahead—the hexagonally planned Bond House (1955), Frankston; Patrick’s polygonal planned Collins Court (1955), Carrum Downs; and the hemispherical Gibb House ‘Sussex Farm’ (1957), Dromana—pre-empted the geometric designs in Chancellor and Patrick’s later work.

11 cantilevering means to support with a beam or girder so that the structure is fixed at only one end.

Top Burgess House, High and White Streets, Beaumaris, 1957, architects Chancellor & Patrick

Bottom left ES&A Bank cnr. Elizabeth and Franklin Streets, Melbourne, 1959–1960, architects Chancellor & Patrick

Bottom right ES&A Bank. Cheltenham, 1955, architects Chancellor & Patrick

Chancellor and Patrick’s exploration of geometry, structure and suspension, especially in their McCraith House design, invites comparison with work by other mid-century avant-garde Melbourne architects. Roy Grounds was interested in primary geometries in plan and form. This is evident in his triangular Leyser House (1951–52), Kew, and circular Henty House (1951–53), Frankston. The small, raised Henty House, with a balcony overlooking the bay from Olivers Hill, became generally known at the time as the ‘Round House’ and was a landmark for travellers to the Mornington Peninsula. Mockridge Stahle & Mitchell designed a butterfly roof for the 1955 Johnson House, Beaumaris, which is still admired by the community. Their interest in geometry continued, particularly in ecclesiastical work, such as their circular planning for the Church of the Mother of God (1957), East Ivanhoe. Robin Boyd suspended his Bridge House (1955) over a creek at Toorak. The house was seemingly wedged between a double-arched framework. Peter McIntyre also explored geometry in the 1950s. His interest in primary shapes is evident in works such as Beulah Bush Nursing Hospital (1952); the Snelleman House (1953), Ivanhoe; and the Brunt House (1953), Kew. McIntyre’s River House (1955), Kew, like the McCraith House, was a bold experiment in suspension, structure, and geometry. Sited on a steep riverbank, the house seemed to hang amongst the trees on a tall A frame. The triangular theme extended in the plan and facade.12 As with much of McIntyre’s 1950s architecture, bright colour was used to create a sense of hierarchy and modernity.

Colour was also an important feature of the McCraith House. Chancellor used yellow and grey, having previously used yellow for the roof of his own house in Gulls Way, Frankston. Shadow grey was used for the outer weatherboards, ground floor doors, and three walls of the living area. This played against a turquoise west feature wall and kitchen cupboards. Citrus and primrose were used throughout for the ceilings on both levels, including the verandah and covered area. The front door and sashes on the facade were oriental red and were set against white window frames, the steel pipe framework, stair details, and trims. Dark grey was used for the weatherboards on the ground floor wall.13 The McCraith House was one of the last Chancellor and Patrick works where colour featured so prominently. From the mid1950s they turned to the use of natural materials, such as brick, timber and stone.

12 philip goad, ‘mcintyre, peter & dione’, in The Encyclopedia of Australian Architecture, eds philip goad & Julie willis, (new york: cambridge university press, 2012), 443–4.

13 the walls of the main bedroom were lilac, the second bedroom and laundry shower Jamaica tan. david chancellor specification sheets 1&2, 5 July 1955, rmit design Archives.

Top Henty House, Frankston, 1952, architect Roy Grounds

Bottom Triangular House, Studley St, Kew, overlooking Yarra River, 1952, architect Roy Grounds

David Chancellor has spoken often of Gerald McCraith as a wonderful client and, following the McCraith House job, the two became lifelong friends. There were further commissions from J. A. & G. McCraith Pty Ltd that included a 1955 McCraith Company house at Niddrie (now demolished) and ongoing factory and commercial jobs.14 However, it was Chancellor’s design for the McCraith House that touched the pulse of avant-garde architectural ideas during a period of intense innovation and simultaneously met the desires of a changing culture. Throughout the years the McCraith House has been maintained to its original condition. It is clear the family experience that strong sense of belonging that Neutra wrote of as ‘soul anchorage’.15 The house has been generously gifted by the family to RMIT University and is now used as a retreat for writers and creative artists. It seems fitting that those given the opportunity to live there for a time may experience that same sense of ‘soul anchorage’, and explore further their own ‘will to experiment’.

Opposite View of McCraith House from front yard, n.d.

14 J. A. & g mccraith pty Ltd was a company run by Jack and gerald mccraith. For details of these commissions see ‘chancellor and patrick 1950–70: A working catalogue’, in callister, Anchoring Identity, vol. i, 230, https://bridges.monash.edu.

15 ‘Architecture beyond the eye’, Architecture and Arts, vol. x, no. 2, February 1962, 37.

‘It was Chancellor’s design for the McCraith House that touched the pulse of avantgarde architectural ideas during a period of intense innovation and simultaneously met the desires of a changing culture.’

WINSOME CALLISTER

The Build

COMMISSIONING

In the early 50s when Gerald McCraith’s business was booming, Gerald and his wife, Nell, purchased a block of bushland overlooking Dromana Beach. The initial commissioning of the Butterfly House began in 1955, after Gerald first met David Chancellor. Gerald’s request for a holiday house was met with experimental and extraordinary sketch plans that moved to the development process with a singular, albeit minor, change; the bedroom and bathroom position on the first floor.

The first notice the McCraith’s received from Chancellor and Patrick on 25 February 1955, informed them of Chancellor and Patrick’s ongoing discussion with K M Steel regarding the structural details of the plan. It also included an estimate quote for the value of the house at £3,700. Later, on 5 April 1955, Gerald McCraith received a receipt for a £100.0.0 payment made towards the total value of £134.0.0 for the preparation of the sketch plans, structural details and slab details, leaving his account balance at £34.0.0.

FRAME

On 25 March 1955, Chancellor and Patrick wrote to Gerald McCraith, acknowledging Frank Dixon’s evaluation of the plans for the McCraith House. Frank Dixon was the structural engineer who assessed and approved Chancellor and Patrick’s experimental design of the steel frame. As an architect and structural engineer, Frank was not afraid to make bold moves. In 1978, he built the iconic Pole House, located at Fairhaven along the Great Ocean Road. The house sat on a slim concrete stalk, a design that defied convention and, seemingly, physics. For the approval of the unique steel frame of the McCraith House, it is unsurprising that Chancellor and Patrick contracted a structural engineer who, like them, approached architecture with a bold and brave attitude.

The geometric steel frame of the McCraith House was prefabricated offsite, thus making it an important factor in the economic viability of the house. Following World War II, Australia found itself in urgent need of infrastructure and faced a shortage of roughly 350,000 houses. Prefabrication involved using factory machines to construct house frames in sections, which were then transported to the building site to be assembled quickly and easily. This allowed homeowners, such as Gerald and Nell McCraith, to capitalise on the economic benefits of fast factory production and reduced labour costs.

Top Letter to Gerald McCraith regarding steel and cost estimate from David Chancellor, 1955

Bottom Letter to Gerald McCraith regarding design approval from Chancellor & Patrick Architects, 1955

Top Construction of McCraith House, 1955

Bottom Construction of steel frame for

McCraith House, 1955

McCraith House, 1955

WELDING

In April 1955, Gerald and Nell McCraith hired the Hobart 300 AMP D.C. electric portable welding set from McAuley Bros Pty Ltd for the construction of the McCraith House. The welding set cost them £15 pounds, with an additional £1 for insurance, and was manufactured by Hobart Brothers metal company. During the depression era, manufacturers of welding equipment sought to increase the need for their technologies by promoting the idea of the welded house. Hobart Brothers became involved in the welded house movement and began producing homes that sold for US$4,000.

Welded homes were designed to be mass-produced. Steel panel sections were factory welded and then brought to the building site and assembled using electric arc welding. As the cost of steel was still significantly higher during the post-war period, the welded house trend did not significantly kick off in Australia until the late 1960s. Thus, the McCraith House was at the forefront of Australian architecture not only in its design, but in its materials and method of construction.

Top left McCraith House slide of steel footings , 1955

Bottom left and opposite Welding the frame for McCraith House, 1955

CONCRETING

G. H. Reid and Sons were the concreting tradesman for the McCraith House. The concrete footings bolted to the triangulated truss frames are a pertinent feature to the home, adding a rural yet affluent influence on the bold and architectural aesthetic of the house. Although it was not unheard of to use concrete as a building material in the 1930s and 40s, it became more common in residential builds in the 1950s due to the post-war restrictions on imported timber (with the restrictions lasting nearly 10 years). The concrete details of residential homes in the 1950s were mainly featured across ground floors, where they laid concrete directly onto the ground beneath it, independent of its surrounding walls.

Once just an architectural element of the McCraith House’s construction and now a predominant feature of its design and artistic impression, the concreting slabs are an important feature of the integrity of the house and a true testament to the time it was built.

Opposite Concreting machine used for McCraith House build, n.d.

G. H. Reid & Sons invoice to Max Howell for McCraith House, March 1955

Right

Right

THE BUILDER

The building receipt and account were received by the McCraith family from M. K. Howell (Max Howell) in late 1955, following the construction of the McCraith House. The invoice, dated 1 November 1955, details the amounts issued and received. The final amount owing was £659 17s 1d, the equivalent of which today would be $23,879.72. Max Howell, an independent builder based in Dromana, Victoria, studied carpentry and drafting at Swinburne Technical University. Howell lived just across the road from the McCraith House, and his involvement in the construction of the house is reflective of how the McCraith family sought out local tradespeople to help build their home in Dromana.

As the house was built before the luxury of electric tools were widely available, Howell built the house completely by hand from prefabricated parts. He laboured against the heat and rocky soil, digging the site with a shovel and levelling it with powdered concrete mixed in a wheelbarrow. Although the design of the McCraith House was complex with many obtuse angles, his unique technical skills were able to bring to life David Chancellor’s vision.

THE SUPPLIES

Max Howell, the builder of the McCraith House, sought out local suppliers around Dromana to contribute to the construction process. Dromana Timber and Builders

Supplies stocked a large variety of the construction supplies needed: from timber, cement, bricks, tiles and paint; to stoves, sinks and more.

Howell received an invoice from Dromana Timber and Builders

Supplies dated 30 May 1955, which included a list of the materials provided. The total cost came to £182 6s 1d, the equivalent of which today would be $6,611.05. The fee for labour and use of machinery covered a large percentage of the total cost, coming to £103 13s 7d. The minimum weekly wage in the 1950s was approximately £6; therefore, the construction of the McCraith House would have made a positive impact on the economy of the community of Dromana.

MCCRAITH HOUSE II

Gerald and Nell McCraith further commissioned the McCraith House II from David Chancellor to serve as a prototype for six houses to be sited on a large parcel of land opposite the McCraith House on Atunga Terrace. Though there were six houses originally commissioned, only three were eventually built. The McCraith House II shared some similarities with the McCraith House: it was sited on a steep slope, and it was built with an innovative steel frame structure and triangular theme in a raised-house form. Chancellor’s final design for the McCraith House II developed from his 1955 sketch plan and included a triangular vertical timber house raised on the north, with a laundry and shower room on the ground level and an open plan lounge and dining room that extended out onto the balcony and provided the same leisurely lifestyle as the McCraith House by overlooking the distant views of Safety Beach and Port Phillip Bay.

Top Side view of McCraith House II wooden frame, n.d.

Bottom Back view of McCraith House II during construction, n.d.

Opposite View of McCraith House II front porch, n.d.

The Fittings

COLOUR SCHEME

The paints used in the McCraith House were commissioned from Taubmans Pty Ltd, a prominent paint company established in 1912 by brothers George and Nathaniel Taubman in Sydney. Taubmans is still in operation today. The colour scheme showcases a variety of Revelite (inside) and Butex (outside) paints, listing the rooms of the house with the corresponding paint colours. The themes chosen reflect the clean-cut geometric shapes and primary colours used by the Bauhaus, a German school of architecture founded in 1919 by Walter Gropius that radically traversed the fine arts and design. The use of distinct primary colours mirrored the essence of the Butterfly House with its strong exterior frame and bold design. The striking external colours, most notably oriental red and citrus, contrast the leafy green landscape of Dromana, making the McCraith House an iconic landmark still to this day.

Left Colour scheme for McCraith House, 1955

Opposite Colour scheme for McCraith House, 1955

FLER FURNITURE

The furniture of the McCraith House epitomised mid-century modern style. Yet at its core, it remains undeniably family focused. The house boasts a low wooden coffee table constructed by Wayne McCraith (Nell and Gerald McCraith’s grandson) alongside endlessly repaired multicoloured tile coffee tables, the frames of which were made by Nell and Gerald McCraith themselves. The house is furnished with a blend of beloved family treasures and items designed by renowned designers from the period. The most notable of the designer decor includes the red dining chairs, produced by modern-furniture business, Fler Furniture.

Fler Furniture was founded by two Jewish migrants working side-byside in a two-horse stable. Fred Lowen and Ernest Roderick helped to define the mid-century Scandi-Pacific style and their combined initials created the iconic business name. The two met inside Tatura Internment Camp in 1941 after they fled Nazi Germany. This camp was used to detain ‘enemy aliens’, particularly German migrants, during World War II. In 1946, they founded the business Fler Furniture. The industrious team produced their popular spindle-legged dining room chairs in 1948. Their design showed early signs of what would eventually become their iconic style, and appear in the McCraith House: simplistic, light and modern.

Opposite

The lounge and dining room, with Fler Furniture’s iconic dining chairs pictured at right. (The Design Files, 2017)

BUTTERFLY PORCH CHAIRS

In October 1955, McCraith House acquired six yellow B.K.F., or ‘Butterfly’, chairs for the upstairs balcony. The iconic B.K.F. chair was originally designed in Buenos Aires in 1938 by Antonio Bonet, Juan Kurchan and Jorge Ferrari Hardoy, who formed the architectural collective Group Austral. The design takes its inspiration from the Tripolina chair, invented by Joseph B. Fenby in 1881 and recognised today as the classic camping chair.

The Butterfly chair quickly became a mid-century staple all around the world, thanks to its lightweight, portable nature and tough canvas durability. The chair’s relaxed seat and lack of armrests, designed for ‘siesta sitting’, removed many of the formalisms of traditional seating and introduced a new sense of conviviality to social seating that would continue to thrive through the post-war years as modernism began to hit its stride.

Left Evan Evans invoice for porch chairs for McCraith House, October 1955

Opposite top The original designs of the Butterfly chair by Buenos Aires collective Group Austral (right) and a modern replica from Precedence Interiors in Melbourne (left)

Opposite bottom Interior view of McCraith House, Homemaker magazine May 1956, showing the Butterfly chairs on the balcony

LIGHTING

Brown Evans and Co. (BECO) was a Melbourne-based lighting company and a pioneer of mid-century avant-garde interior design. Though only in operation between 1946 and 1960, BECO was (and still is) regarded as one of Australia’s foremost architectural lighting designers. BECO’s unique sconce design (sconce meaning any kind of wall-mounted lighting fixture) was characterised by a conical or cylindrical shade, usually in a brass, silver or painted finish and connected to the wall mount by a swivel arm designed for altering the light space in the room.

The invoice indicates that the original lighting design for the McCraith House included the BECO 500 model (a single wall light with adjustable reflector for over the bed or desk), the 502 model (similar to the 500 model but with two fittings connected to a single wall mount, designed for both indirect and direct lighting) and the 504 model (designed to be mounted higher towards the ceiling and fitted with a higher wattage to flood more of the space with light). Second-hand BECO lighting fixtures are now rare and highly sought-after mid-century pieces that are predominantly restored and sold through upmarket vintage furniture resellers. A range of BECO lighting was even featured on a 2021 episode of ABC’s Restoration Australia. The timeless charm of these unique fixtures proves that the McCraith House was an idyllic model of mid-century Australian design—right down to the last detail.

Above R. B. Hipwell invoice for lights for McCraith House, 1955

Opposite The dining area, with original wall-mounted conical brass lighting fixture

NAMING OF THE HOUSE

The word ‘Larrakeyeah’ comes from the Larrakia people, who are the Traditional Owners of the Darwin region. The Larrakia people also refer to themselves as ‘saltwater people’ due to their close relationship with the sea. Gerald McCraith chose to name the house after the Australian Army barrack where he served from 1940–44, as a tribute to the years he served and the people he served with. Darwin’s Larrakeyah Barracks, established in 1933, provided training for army recruits, teaching young men to fight and adjust to the army way of life. By choosing to name the McCraith House ‘Larrakeyeah’, Gerald McCraith brought the memory of his time in service to the Mornington Peninsula and kept the Larrakeyah name and memory alive for himself and his family for years to come.

Top Detail of the original sign for McCraith House

Bottom left Letter from Public Library of Victoria concerning meaning of the word ‘Larrakeyeah’, December 1955

Bottom right Letter from Public Library of South Australia concerning meaning of the word ‘Larrakeyeah’, January 1956

The Garden

TANKS AND WATER SUPPLY

On 25 October 1955, Chancellor and Patrick wrote to Gerald and Nell McCraith to inform them that, as the water pressure in Palmerston Avenue, Dromana was already very poor, the State Rivers and Water Supply Commission ‘would not hear of a pump or any other means’ to provide a stronger water supply to their house. As the state could not adequately supply the property with water, it was necessary for the McCraith family to use tanks to collect and store rainwater.

The McCraith House is known as the ‘Butterfly House’ for its inverted gable roof which, like most of the design features of the house, served a function. The roof, commonly referred to as the butterfly roof, was used for more than just creating the eye-catching effect of their signature angular style. Its purpose was to act as a catchment for rainwater that on a regular roof would be drained off.

The butterfly roof was originally designed by SwissFrench architect Le Corbusier in 1930, but it wasn’t until the 1950s that it became popularised through American architect William Krisel as a common feature of post-war homes in the California desert region. A butterfly roof is a roof shape that, like the name suggests, resembles butterfly wings. The inward sloping of the McCraith House roof allows water to be collected at the valley. This is then collected through a drainage spout and transported down to the collection tank—a thousand-gallon galvanised water tank that was elevated above the house so it could supply the house with water by force of gravity.

The use of the butterfly roof as a rainwater harvesting and storage method represents an auspicious combination of aestheticism and functionalism. Chancellor designed the house to suit the environmental and economic needs of the locality, while retaining the sleek form, typical of mid-century modern style.

Above Back view of water tanks for McCraith House, n.d.

Left Letter from David Chancellor to G. McCraith concerning the installation of water tanks, 1955

NELL’S GARDEN

The McCraith House, with its sweeping, north-west facing windows, looked out on not only the breathtaking views of the Mornington Peninsula, but also the charming rainbow-coloured garden of the property. The brightly coloured banks of succulents and blooms in the front garden, which were carefully nurtured by Nell McCraith, provided a striking contrast to the modernist architecture of the McCraith House. Nell was an avid gardener who spent most of her time outside, cultivating her garden to complement the natural flora of the surrounding area. She loved succulents, planting several species such as the Australian pig face (also known as karkalla) throughout the McCraith House garden, alongside flowering plants such as gazanias and milkmaids. The beauty of Nell’s garden captured her love for outdoors and the Peninsula’s natural landscape.

GERALD’S GARDEN

For Gerald McCraith, gardening was more than just a hobby. During his lifetime, he became one of Australia’s most influential orchidists. In 1931, he became a member of the Victorian Orchid Club of which he was president from 1959–62. Later, he aided the formation of the Australian Orchid Council and became its president in 1964. As president, Gerald was influential in bringing the 6th World Orchid Conference to Sydney in 1969. He was also awarded an Honorary Fellowship by the Australian Orchid Council for his outstanding work and commitment. Gerald’s devotion to the orchid industry was demonstrated by his diligent attendance of the World Orchid Conferences, which he attended every year from 1963 in Singapore to the 17th in Malaysia in 2002. In 1976, Gerald co-founded the Australian Orchid Foundation, a voluntary not-for-profit organisation dedicated to the promotion of Australasian Orchids. Gerald continued in his role as director of the foundation until February 2008 when he was 99 years of age. At the 18th World Orchid Conference held in Dijon, France, Gerald was awarded an Orchid Society of Southeast Asia Fellowship for his contribution to the development of orchid interests, conservation and cultivation in Australia. In 1986, Gerald was successful in achieving his lifelong goal to have Australian Native Orchids featured on a set of Australian stamps issued by Australia Post. His appreciation of and dedication to the cultivation of orchids, which was reflected in his garden at the McCraith House, was honoured in 1995 when orchid specialist Phil Spence registered an orchid hybrid in his name: Dendrobium Gerald McCraith.

Opposite Gerald in the garden at McCraith House, 1977

Below Note written on reverse of photo pictured opposite

Family, Donation, Refurbishment and Legacy

Family and Community

THE MORNINGTON PENINSULA

The McCraith House overlooks Dromana Beach, a picturesque location with a distinctive curved coastline and sense of serenity that is typical to the Mornington Peninsula. The natural environment of Dromana flourished when the McCraith House was built in 1955. With the hills surrounding Dromana less heavily populated with houses and infrastructure, the trees, bushes, plants, and grass grew freely in the open spaces. There are over 700 native plants on the Mornington Peninsula, making up almost one-fifth of Victoria’s flora.

A heavy thicket of trees covered the hilltops that surrounded Safety Beach. Tufts of hardy grass and bushes stretched as far as the eye could see, creeping right up to the beach’s sandy edge. The sand was derived from two different sources. North of Dromana the bathing beaches were derived from Baxter Sandstones which had been cut deeply by coastal erosion; and south of Dromana, sand was mostly derived from dune rock.

Unsurprisingly, people flocked to the area after the intensity of World War II looking to settle into slower and calmer lifestyles by the beach. Though it eventually flourished as a bustling trade hub, it remained a haven for those who saw the pursuit of relaxation and leisure to be as important as work and commerce. Dromana was an inviting community and the township encouraged experimental architecture. With holiday homes popping up along the coastline of Port Phillip Bay, the ‘Larrakeyeah’ was swiftly woven into the fabric of the community and found its place amidst the views, beaches, manna gums and welcoming arms of Dromana and the Mornington Peninsula.

Previous Bin Dixon-Ward, Lois Dixon-Ward and Kerryn Dixon-Ward

Top View of Port Phillip Bay from the McCraith House, 1958

Left View of the McCraith House from the garden, c. late 1950s

Opposite Safety beach, Dromana, c. 1980

‘After all the chores were done, we got to go down to the local beach. Our family had a boat shed with a little rowing boat, and a kettle and deck chairs and all the stuff you need for a good day in the sun. If it was a nice summery day, my grandmother would use one of those big electric frypans to cook up a big Sunday lunch. I even learnt how to walk on that beach!’

BIN DIXON-WARD, GRANDDAUGHTER OF GERALD AND NELL McCRAITH

‘Larrakeyeah, popularly known as the Butterfly House, was my grandparents’ holiday house in Dromana. We had two types of holidays there. One was a short weekend stay and the other would be an extended couple of weeks during school holidays. My grandparents lived in Essendon during the week and would drive down the Nepean Highway to Dromana on the weekends. My family lived in Frankston, which is on the way. They would often drop in on their way so quite often my sister and I would jump in the car with them, and all go down together, giving Mum a break.’

BIN DIXON-WARD, GRANDDAUGHTER OF GERALD AND NELL McCRAITH

Esplanade,

‘I loved the bunk room. It is really quite a small room, with six single beds. They all had their own lamp, so when you had your own bunk, it felt like your own little cubby area. The game was always who could get up to the top bunk without a ladder, and who was brave enough to jump down again. And, as kids, of course we always could! We’d drape sheets everywhere and have our own tiny caves. We had our own favourite bunks for particular reasons. There was one master bedroom upstairs and that was my grandparents’ room. No one else ever slept there, so whenever anyone else came—parents, kids, visitors, anyone—they slept in the bunk room.’

BIN DIXON-WARD, GRANDDAUGHTER OF GERALD AND NELL McCRAITH

THE FAMILY

In 1930, Nell and Gerald McCraith were married. They had two daughters named Lois and June and would often travel to the Mornington Peninsula from their home in Essendon on weekends to enjoy family time. The McCraiths were a generous family, which they expressed through contributing to organisations and by service to the community. For instance, Gerald was the president and co-founder of the Australia Orchid Foundation, a not-for-profit organisation dedicated to promoting Australasian orchids. Nell’s acts of giving could be felt by her loving presence within her home by her children and, eventually, her grandchildren.

Gerald showed particular generosity towards homeless people who resided near the old fish markets on Flinders Street where Gerald ran his rabbit export business with his brother Jack. Gerald and Nell’s granddaughter, Bin DixonWard, says that Gerald would often offer work to those in need, first in the rabbiting business and later during the construction of the McCraith house. Due to the lack of mental health support for returned soldiers at the time, war veterans often ended up without work, shelter or a support network. Gerald, having served in the army during World War II, had an affinity for the returned servicemen, and offered them a chance to work and connect with some mates again.

Bin Dixon-Ward remembers spending school holidays at the Butterfly House, cozied up in the six-bunkbed bedroom with all her cousins and sisters. Summers for the grandchildren meant barbecues, days spent down at Safety Beach and getting their hands dirty in Nell and Gerald’s gardens. The McCraith House is a cultural icon, a legacy to Chancellor and Patrick’s innovative modernist architecture, but before it was an icon, or even the Butterfly House, it was a home. The ‘Larrakeyeah’ was a loving home for Nell and Gerald McCraith, their daughters, June and Lois, and grandchildren, Graham, Wayne, Michelle, Bin and Kerryn.

Top The ground floor of McCraith House, showing carport and stairs, 1955–56 Opposite The McCraith family at the house for Christmas, 1967

‘There were always chops and sausages on the barbie. I still remember the smell of wood-cooked barbecued meat; charred on the outside and dripping with juices. Around the side of the house my grandfather built a big wood-fire barbecue out of stone. It had a fancy ironwork bracket that was salvaged from the Flinders Street Fish Markets when they were demolished in 1959, and a built-in table. When they were laying the stone for the barbecue, they got all the family, me included, to put our footprints in the concrete. And they’re still there! All those little footprints from 1962. I would have been about two years old.’

BIN DIXON-WARD, GRANDDAUGHTER OF GERALD AND NELL McCRAITHRABBIT KING

The Rabbit King by Catherine Watson tells the story of Jack McCraith, Gerald’s brother and a leading figure in Australia’s once booming rabbit industry. With nothing but a bicycle and a will to succeed, Jack entered the rabbit export trade in the early 1930s at the age of fifteen. Watson reports Jack’s summary of his business strategy: ‘Everyone knows how to catch rabbits, I’ll learn how to sell them’. In 1944, when Gerald was discharged from the army, he joined his brother in the rabbiting business, and together the pair used their transport infrastructure (such as refrigerated trucks) to supply rabbits to feed troops across Australia. By the late 1940s, they had captured the market and were operating one of the most successful rabbit export trades in Australia.

The rabbit industry contributed to the prosperity of the Australian economy during the harsher periods of the mid-twentieth century, when rural areas were affected by war, depression and drought. From the mid-1940s to 50s, rabbit carcasses were worth 24 pence a pair. The refrigerated trucks allowed the McCraith brothers to transport rabbits from rural areas (coming from as far as Western Australia) to their factory located at the old fish markets on the banks of the Yarra River in Melbourne. Through innovative export models and business practices, Gerald and Jack survived the economic hardships of the time and prospered to become exporters of over 130 million rabbits during the company’s 40 years of operation.

‘Weekends at the house meant there were regular jobs to do. We never got away with just going there and hanging out. There was always something, like pulling out weeds or mowing the grass—and there was a lot of grass. Sometimes there would be a painting job going on or we would have to sand rust off the metal—I hated that! I hated the feeling of rust and the smell of it. Because the framework of the house is steel, it was a lot like the Sydney Harbour Bridge; it was a constant process of painting and sanding rust.’

BIN DIXON-WARD, GRANDDAUGHTER OF GERALD AND NELL McCRAITH

CHRISTMAS IN THE BUTTERFLY HOUSE

In December 1955, the McCraith family (Nell, Gerald and Lois at the time) had the joy of celebrating Christmas in their newly finished holiday home. The momentous occasion was proudly celebrated by the family, which is shown in the McCraith family Christmas card from 1955. The McCraith House would become a Christmas destination for the growing family over the coming years. The family hosted their 1967 family Christmas at their holiday home, sharing the house with extended family for the day. The Christmas card displays, not a photo of the family (a common feature of family Christmas cards) but, rather, a bold photo of the exterior of the new home, sharing their pride with all who received a Christmas card from the McCraiths that year. This shows how the Butterfly House had, in its short time of existence, become a special part of the McCraith family.

Above McCraith family Christmas Card, c. 1955

‘My grandparents spent extended periods of the summer holidays on the Peninsula. They knew a lot of the neighbours; they knew people on McCulloch Street and the people who lived in the three houses in Atunga Terrace. My grandparents actually set up the Dromana Bowls Club. They were part of a big group who would go there during the bowls season. I remember they had their whites, their hats, their special shoes and bags of bowls. And they always won something! They were always bringing some trophy back to the house.’

BIN DIXON-WARD, GRANDDAUGHTER OF GERALD AND NELL McCRAITH‘The only heating was a potbelly stove that required firewood be cut. The adults used the axe but us kids got to use one of those two-person saws. That was a bit of fun and always felt like an adventure or something dangerous. Doing work around the house as a kid made me pretty comfortable with tools and hard work. I’m not afraid of a lawnmower or a saw now.’

BIN DIXON-WARD, GRANDDAUGHTER OF GERALD AND NELL McCRAITH Potbelly stove (The Design Files, 2017)

Potbelly stove (The Design Files, 2017)

Donation, Legacy and Refurbishment

‘When my grandfather died in 2009, he was 100 years old. My mum was already an older woman by then and the responsibility of looking after the house and garden was too great. So that’s when we started talking about whether we wanted to keep it in the family or not. There was this fear of what would happen to it. It had been heritage listed for quite some time and the thought of someone building something on the back of it or changing the scope of it didn’t sit well with us. We knew it was architecturally and culturally important. The house had been the focus of several exhibitions, magazine features and profiles, including at the Mornington Gallery. I was studying at RMIT at the time, so I had a knowledge of the architecture and design program here and could see how it might be of some use for students or researchers of design history. We approached Margaret Gardner, the vicechancellor of RMIT at the time, and within just a few weeks the university came back to us with a great proposal about using it as a creative residency space, and it just made sense. The fact that it’s now used by artists and creative practitioners is terrific. It’s lovely to know we have contributed in a small way. I thought the refurbishment by Peter Elliott Architecture was really sensitive, and it blended well into the original design, including some of the colour that had been changed over the years, putting back the original colours.’

BIN DIXON-WARD, GRANDDAUGHTER OF GERALD AND NELL McCRAITHDONATION

The McCraith House was donated to RMIT University in 2013 by Gerald and Nell McCraith’s daughter, Lois Dixon-Ward, and her two daughters, Bin Dixon-Ward and Kerryn Dixon-Ward. The donation was, as stated by RMIT University, ‘one of the most significant gifts to RMIT University to date’.

The official handover took place in June 2013, during an informal morning tea where the Deed gifting the house to the university was signed. According to Peter Elliott, the house had been beautifully maintained over the intervening years. It was donated with its original furnishings and crockery in situ, amplifying, simultaneously, the modernist style of the interior and relaxed atmosphere of a family beach house. The gift also included an archive of the house’s design, construction and use by the family. The collection includes correspondence with the architects, the original designs and working drawings for the house, the specifications, invoices for the construction, and the family’s home movies showing the design and construction of the house. These are now held in a collection by the RMIT Design Archives.

Lois Dixon-Ward and her daughters donated their treasured family home with the desire to create a space that is both intellectually invigorating and refreshing. Like other modernist designs, the McCraith

House has a focus not on decoration but on spatial quality— simplicity of lines and the organisation of space from a functional perspective. The sense of expanse felt in modernist homes is inherently linked to freedom of thought. With its bold, angular forms, panoramic views and masterful control of light and space, it is the ideal place for creativity to flourish.

The donation was accompanied by an endowment to support ongoing maintenance. To mark this gift, RMIT University established a creative residency program. Carrie Tiffany, author of the novel Mateship with Birds (2012) was the first to undertake a creative residency at McCraith House in 2013 and, as of 2022, it has housed a plethora of individuals from varying creative disciplines.

Bin Dixon-Ward put it best when she said, ‘My grandparents loved nothing more than having family and friends enjoy their special holiday house. My sister Kerryn and I both benefited from their belief in the value of curiosity and education. Our family is humbled to be able to honour them by supporting education and research at RMIT, particularly in the field of art and architecture. Nana and Pa would have been thrilled to see the house injected with a new lease of life’.

LAUNCH

A morning tea was held at the McCraith House to mark the official document handover to RMIT University in 2013. The event was attended by Lois Dixon-Ward, Bin Dixon-Ward and Kerryn Dixon-Ward; as well as the original architects of the house, David Chancellor and Rex Patrick; and RMIT University’s Vice-Chancellor and President at the time, Professor Margaret Gardner. The McCraith House residentsto-be Hannie Rayson and Carrie Tiffany were also present. After the signing of the Deed of Gift both Carrie and Hannie were given a tour of the area by Lois Dixon-Ward.

‘Across October and November I came to Melbourne from London to work at The Big Anxiety, a festival exploring arts, science and mental health. Staying at McCraith House after an intense period of work and research provided me with the time and space to do some deep thinking and reflecting on the work that I do. Often my work is emotionally taxing, often tackling complex mental health themes rooted in my own lived experiences. I spent my time at the house thinking about how to ensure the sustainability of my practice, and deeply thinking about aspects of active rest and the space before, after and in between my work, space to process the impact the work has on myself emotionally and psychologically. Having no pressure to “create” something, but simply time to think, rest, reflect, walk and feel—all in the beautiful surroundings of the Mornington Peninsula—has made me feel more prepared to implement a framework of care for myself in the work that I do when I return home.’

DANIEL REGAN

‘I feel very privileged to have been given this opportunity, after the devastating year that 2020 was for everyone. I was able to immerse myself into my practice for an entire two-week period in the amazing McCraith Butterfly House, looking out every day onto an ocean view which is every artist’s dream. I used my time at the residency to do uninterrupted research into my continuing project Yeki Bood Yeki Nabood (There Was One, There Wasn’t One/Once Upon a Time).’

HOOTAN HEYDARI‘I was based at the McCraith House in Dromana from Monday January 30 to Saturday February 11. It was invaluable. I used the time to reconnect with a novel that I started ten years ago called This Devastating Fever. It was based on the life of Leonard Woolf, with particular focus on his time as a public servant in Ceylon (1904–1911), the early years of his relationship with and marriage to Virginia, her breakdown, and the outbreak of WW1.

One of the things I needed to figure out is why the novel had stalled, particularly given that the writing I had done on the project (some 20,000 words) was, arguably, stronger than I’d managed to produce for my first two novels. The retreat allowed me to realise I was struggling with just how contested this area of history is, and the wealth of detail that exists in the public realm about these two writers. I took a couple of significant steps. I cut the cord between the novel and “real life”. My research on this period of history, and indeed Leonard and Virginia, remains vital, but I’ve changed their names, which has had the effect of releasing me from what did, or didn’t “really happen”. The second step was to connect book, emotionally anyway, to the current political climate.’

SOPHIE CUNNINGHAM‘I powered through 21,000 words to finish a draft of my manuscript and was reminded again of what a magical place it is. I got MONTHS worth of thinking and writing done and can go home with a FULL DRAFT (whatever that means). I am incredibly lucky and honoured to have had this time and space courtesy of RMIT.’

KATE MILDENHALLREFURBISHMENT

In 2015, Peter Elliott’s refurbishment of McCraith House brought the iconic mid-century home into the contemporary world. The skilled restoration was acknowledged with the Recognition of Excellence in Restoration and Refurbishment of a Heritage Place by the National Trust, Mornington Peninsula Heritage Awards in August of 2015. The annual award seeks to recognise integral parts of the community and ‘excellence in retention, restoration and reuse of our heritage places’.

‘After the lockdowns of 2020, it was a privilege to be able to return to my novel manuscript in the stunning setting of the Butterfly House. Time and space to think are rare enough—but what this residency provided was even rarer, a particular quality of time and space that was slow, calming and inspirational.’

ANDRÉ DAO”Peter Elliott is one of Australia’s most renowned architects. In 2017 he received the Gold Medal from the Royal Australian Institute of Architects, which recognises distinguished Architects in Australia. He has a special relationship with RMIT University, as he has been involved in the transformation of RMIT University’s City Campus for over 20 years. His practice, Peter Elliott Architecture & Urban Design, specialises in public commissions, including urban infrastructure, education, arts and the community. Peter Elliott’s designs, completed works and writings have appeared in design journals across Australia and internationally.

Elliott paid meticulous attention to maintaining the modernist interior and 1950s character of the McCraith House, while observing modern health and safety requirements. It’s due to this skilful care and craftsmanship that the house remains a prime example of structural modernism. Kevin McCarthy, Deputy Director, who oversaw the restoration spoke of the importance of maintaining the McCraith House: ‘The National Trust award not only recognises how we protected this particular building for generations to come, the Butterfly House also demonstrates how RMIT reaches people across generations’.

Opposite Refurbished lounge and dining room and balcony, McCraith House, 2015, architect Peter Elliott

‘During my time at McCraith House I rewrote an extended essay I’d put in a drawer last year after coming to a structural impasse. “First Blood” is a fragmentary and lyrical essay which wrestles with questions of cinema and nation, trying to find a form which can encompass the stories Australian cinema represses as much as those it chooses to tell; it is about bushrangers, film decay, sublimation, myth, ghosts, fire and danger (moral and physical). The residency gave me the time and mental clarity to sit with these jigsaw pieces, move them around each day, and gradually understand how they slotted together.’

REBECCA HARKINS-CROSS

Dining room and BECO light fixtures (The Design Files, 2017)

‘My residency at McCraith House was the first block of dedicated, sustained writing time I’d had in eighteen months, and it was incredibly useful and productive. I have been working on a second novel for close to two years now, but during that time I have also been working full-time running my own business. This residency allowed me to immerse myself in the project in a way that I don’t get to in my day-to-day life, and by the end of the fortnight I felt that I had made a genuine breakthrough. Primarily, as well as producing more than 10,000 words, I managed to pin down the “voice” I had been struggling to find, almost to the point of despair, over many months. While at McCraith House I began to hear this voice clearly and, consequently, the writing began to flow at last. The time, the solitude, the singularity of focus, the expansive, ever-changing view, the proximity to the ocean, and the beautiful space in which to sit and work, were all instrumental and wonderful. McCraith House is truly a special place, and for me it will always be the place where I finally began to feel good about my second novel.’

EMILY BITTO

‘I emptied the fridge and everything else into my car, secured the premises, turned off printers, chargers, radios and arrived at McCraith House in the freezing side ways hail. Then I reversed over the fridge contents and triggered the house alarm. With the door locked and the heater humming, I remove my bra, settle to read and reacquaint, red editing biro in hand. I told myself the storm beyond the glass wall would cease and the sun would reveal the bay. It would be dramatic and fabulous. Inspiring. A writing session lasts 15 hours and I don’t even notice. My story has a sense of order, the scenes have joined hands to consolidate my intention, the landscape supports the characters as they dramatise the ideas that carry the reader.’

ROSALIE HAMRefurbished kitchen, McCraith House, 2015, architect Peter Elliott

‘My time at McCraith House feels a bit like a dream; I keep looking at my photos to make sure I had been, in fact, “living” there for two weeks. The house has such a beautiful peaceful spirit that I found so restorative and reassuring. (There was also, possibly, one actual spirit—there was a mysterious perfume that would come and go in the hallway ...!) Keeping as many plates in the air as I do can really take it out of me, so the opportunity to just sit on the balcony and stare out over the water and the occasional hoons racing across the freeway on a Saturday night was a true gift. My dad spent his summer holidays in a shack in Dromana, so he was particularly excited that I was continuing the family tradition. What I found especially moving about the house is the way it feels like the family has just gone out to the beach and will be back any minute.’

CLEM BASTOW

‘In June this year, there was an informal morning tea at the house, when the DixonWards officially handed over their treasured holiday home to RMIT. Among the guests was the novelist Carrie Tiffany, who will be the next writer to take up residence here.

After the signing ceremony, Carrie and I were taken on a tour by Lois, whose late husband, Bryan Dixon-Brown was a sea captain. Lois pointed to a ship which sailed into view and then made a sharp left-hand turn towards Melbourne. Lois told us that when her husband sailed by, sometimes after being at sea for many weeks, he would sound the ship’s horn several times. That was her signal to bundle the children into the car and hot-foot it up to Melbourne to collect him from the port.

The Butterfly House and I are almost the same age. I am thinking about our parallel lives. She is a year older, built in the year of the Olympics in Melbourne when my dad bought the first TV in the street and all the neighbours came by to watch.

For all her show of modernity, she seems to me to be exuberantly innocent.

At night, the house floats in a vast black universe, smattered with twinkling lights. The ugly retail sprawl along the Point Nepean Road is gone. The dull, lurking suburbia is also erased by the blackness. At night in the Butterfly House, there is only romance.’

HANNIE RAYSON

PARTNERSHIPS

Since the donation of McCraith House, RMIT has strengthened industry partnerships and supported the creative sector through access to this extraordinary space for a creative residency program. The program offers independent creatives space and time to work on projects whilst being surrounded by the beauty of the Mornington Peninsula.

Residencies are established around strategic partnerships, diversity of voice, form and discipline, the potential for engagement with the community and connection to strategic creative projects. The creative residency program is attached to a number of industry partnerships including Footscray Community Arts Creative and Cultural Leaders’ Program; annual First Nations residencies in collaboration with Chamber Made, Birrarangga Film Festival and Blak & Bright First Nations Literary Festival, as well as a collaboration with the Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards, with an annual residency offered to the winner of the VPLA Unpublished Manuscript Award.

Creative residency participants collaborate on key RMIT projects, work with RMIT students, and appear in public events. Podcaster and artist Honor Eastly undertook a residency in April 2022. Honor’s moving one-woman performance, No Feeling is Final was commissioned and produced by RMIT Culture and presented to a capacity audience at The Capitol as part of the Big Anxiety Festival 2022.

Graduating student residency prizes provide RMIT graduates with the opportunity to immerse themselves in their creative projects within the cocooned environment of the Butterfly House. Logan Ramsay, who was the recipient of the Graduating Student Prize in 2019, completed his visual and poetic project, City of Streams, while undertaking his residency at McCraith House. Logan described the house as ‘a diving bell of clouds and bay to let the craft breathe’.

Korean graphic artist Han Donghyuk travelled to Melbourne from Bucheon to undertake his residency in 2024, describing the experience as ‘almost heaven’, while Indonesian

‘The space and time at McCraith was a true gift to the creative process of making No Feeling Is Final. My time at the Butterfly House was a much-needed break from the demands of the normal world to cultivate space for the essential creative wrestle at the beginning of a big creative project—what is this trying to say? What is essential to this story? How is this story best told? McCraith and its expansive views, long, meandering walks along the beach, and dips in the ocean (even when it’s raining) were the perfect background for this process. Many of the ideas that formed the backbone of the final show I can trace back to that time and space at the Butterfly House. Now when I drive along the peninsula and see the McCraith House from the freeway, I look at it with a sense of immense gratitude for this gift to creatives, and send my love to whoever is currently there on the balcony dreaming up their next big thing.’

HONOR EASTLY

dancer Riyo Tulus Pernando performed in RMIT’s Cultural Collaborations Showcase as part of the ASEAN-Australia summit and was also given the opportunity to undertake a McCraith House creative residency during his time in Australia.

Manager, Partnerships and Engagement Ali Barker said RMIT was proud to be the custodian of this treasured house and program that had enabled wonderful creative endeavours to be hatched by artists and writers, while Professor Francesca Rendle-Short, recalls how McCraith House strengthened RMIT’s connection to the cultural heritage of the land. A Welcome to Country held with visiting international artists and writers deepened the community’s understanding and awareness of the Boonwurrung language groups of the Kulin Nation, the unceded land on which the McCraith House is located.

When asked what her grandfather would think about donating the house to RMIT University, Bin Dixon-Ward laughed and said that he was a pragmatist and would have encouraged them to sell the house and make a profit. She also concedes that Gerald ‘would have been absolutely thrilled to know that it has a new life, that there are people using it’. Gerald McCraith had a lifelong love of learning, innovation and creativity—despite having to leave school at the age of 15. Bin believes that Gerald would have been proud of the relationship between the home and an educational institution, and the intellectual nourishment that the relationship provides to writers, creatives and artists who are offered the unique opportunity to reside there.

Australian and international writers joining Smoking Ceremony and Welcome to Country with Bunurong Land Council Aboriginal Corporation at McCraith House in 2018

‘Such a beautiful building and peaceful environment; Somewhere close to the beach and forest, up on a hill. Kind of ideal place for thinking and writing.

SHOKOOFEH AZAR

IMAGE CREDITS

RMIT Design Archives (RDA) RMIT Design Archives holds the archive for McCraith House that documents the architecture, design and use of a McCraith House (McCraith House collection). The archive was donated by Gerald and Nell McCraith’s daughter Lois Dixon-Ward, and it was used extensively to create this publication. Visit the RMIT Design Archives website www.designcollection.rmit.edu.au to explore the McCraith Collection.

Peter Elliott Architecture (PEA) The McCraith House Refurbishment, 2015, original architects, Chancellor & Patrick 1955, refurbishment by Peter Elliott Architecture + Urban Design, © Peter Elliott Architecture + Urban Design, courtesy Peter Elliott The Design Files (TDF) The Design Files, photography by Eve Wilson © The Design Files

COVER

Front Cover: RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0002.6 © Lois Dixon-Ward Back Cover: (top) RDA Chancellor & Patrick, 0050.2013.0001.1 © Chancellor Patrick & Associates Pty Ltd; (middle) PEA; (bottom) PEA

TEXT

p. 2 RDA unknown, 0050.2013.0013.1 © Dixon-Ward family

PART I: ARCHITECTURE, CONSTRUCTION AND DESIGN

pp. 4–5 RDA David Chancellor, 0050.2013.0001.1 © Chancellor Patrick & Associates Pty Ltd

LARRAKEYEAH: THE WILL TO EXPERIMENT

p. 6 RDA Margund Sallowsky © RMIT University; p. 8 (top) RDA unknown, 0050.2013.0015 © Lois Dixon-Ward p. 8 (bottom) RDA Gerald McCraith, 0050.2013.0021.20 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 11 Library of Congress Collection, https:// www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2005687618/; p. 12 unsplash, https://unsplash.com/ photos/63Es9D5jR5M; p. 14 (top) Julius Shulman, © J. Paul Getty Trust. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (2004.R.10), https://rosettaapp.getty.edu/delivery/ DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE127151; p. 14 (bottom) Homemaker magazine, May 1956; p. 15 Homemaker magazine, May 1956; p. 16 RDA David Chancellor, 0050.2013.0001.8 © Chancellor Patrick & Associates Pty Ltd; p. 17 RDA David Chancellor, 0050.2013.0001.3 © Chancellor Patrick & Associates Pty Ltd; p. 18 unknown © Chancellor Patrick & Associates Pty Ltd; p. 19 RDA Gerald McCraith,

0003.2022.0001.22 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 21 (top) unknown, Commercial Photographic Company, Carlton; p. 21 (bottom left) P. Wille © Chancellor Patrick & Associates Pty Ltd; p. 21 (bottom right) unknown © Chancellor Patrick & Associates Pty Ltd p. 23 (top) L. H. Runting, SLV Collection, https:// find.slv.vic.gov.au/permalink/61SLV_INST/s6pvau/ alma9939658982407636; p. 23 (bottom) Lyle Fowler, SLV Collection, https://www.slv.vic.gov.au/pictoria/ gid/slv-pic-aab85556/1/a38551; p. 25 RDA Gerald McCraith, 0050.2013.0018 © Lois Dixon-Ward

THE BUILD

pp. 26–7 RDA David Chancellor, 0050.2013.0001.8 © Chancellor Patrick & Associates Pty Ltd; p. 28 RDA David Chancellor, 0050.2013.0001.5 © Chancellor Patrick & Associates Pty Ltd; p. 29 RDA David Chancellor, 0050.2013.0026 © Chancellor Patrick & Associates Pty Ltd; p. 30 (top) RDA David Chancellor, 0050.2013.0028 © Chancellor Patrick & Associates Pty Ltd; p. 30 (bottom) RDA David Chancellor, 0050.2013.0027 © Chancellor Patrick & Associates Pty Ltd; p. 31 (top) RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0001.6 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 31 (bottom) RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0001.19

© Lois Dixon-Ward; pp. 32–3 RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0001.27 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 34 (top) RDA Gerald McCraith, 0050.2013.0037

© Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 34 (right) RDA Gerald McCraith, 0050.2013.0025 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 35 RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0001.5 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 36 (top) RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0001.24 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 36 (bottom) RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0001.28

© Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 37 RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0001.7 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 38 RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0003.2 © Lois DixonWard; p. 39 RDA Gerald McCraith, 0050.2013.0039

© Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 40 RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0001.4 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 41 (left) RDA Gerald McCraith, 0050.2013.0035 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 41 (right) RDA Gerald McCraith, 0050.2013.0034 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 42 RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0001.9 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 43 RDA Gerald McCraith, 0050.2013.0031 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 44 (top) RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0003.8 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 44 (bottom) RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2003.0003 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 45 RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2003.0003 © Lois Dixon-Ward

THE FITTINGS

pp. 46–7 PEA; p. 48 & 49 RDA Chancellor & Patrick, 0050.2013.0022.1-2 © Chancellor Patrick & Associates Pty Ltd; p. 51 TDF; p. 52 RDA Gerald McCraith, 0050.2013.0033 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 53 (top left) Courtesy Precedence Interiors; p. 53 (top right) Big BKF Buenos Aires, Santiago Palermo lead Designer; p. 53 (bottom) Homemaker magazine; p. 54 Dianne Snape, PEA; p. 55 RDA Gerald McCraith © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 56 (top) RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0001.12 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 56 (left and right) RDA Gerald McCraith © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 57 PEA

THE GARDEN

pp. 58–9 RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0001.16 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 60 RDA Gerald McCraith, 0050.2013.0021.19 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 61 (top) RDA Gerald McCraith, 0050.2013.0021.16 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 61 (bottom) RDA Gerald McCraith © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 62 RDA Gerald McCraith, 0050.2013.0012 © DixonWard family; p. 63 RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0002.6 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 64 RDA unknown, 0050.2013.0014 © Lois Dixon-Ward

PART II: FAMILY, DONATION, REFURBISHMENT AND LEGACY

pp. 66–7 iStock, tsvibrav

FAMILY AND COMMUNITY

p. 68 Tatjana Plitt © RMIT University; p. 70 (top) RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0002.3 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 70 (bottom) RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0001.16 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 71 RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0002.1 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 72 Rose Stereograph Co., H32492/8878, State Library of Victoria; p. 73 Rose Stereograph Co., H32492/2761, State Library of Victoria; p. 74 RDA Gerald McCraith, 0050.2013.0019 © Dixon-Ward family;

p. 75 RDA unknown © Dixon-Ward family; p. 76 RDA J.A. & G. McCraith Pty. Ltd., 0050.2013.0036.2 © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 77 (top) RDA Gerald McCraith, 0050.2013.0016 © Dixon-Ward family; p. 77 (bottom) RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0001.27

© Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 78 RDA unknown © Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 81 TDF

DONATION, LEGACY AND REFURBISHMENT

p. 82 RDA Margund Sallowsky © RMIT University; p. 86 RDA Margund Sallowsky © RMIT University; p. 89 Dianne Snape, PEA; pp. 90–1 TDF; p. 93 PEA; p. 94 PEA; p. 97 PEA; p. 99 RMIT Culture

© RMIT University; p. 100 (clockwise from top left) RDA David Chancellor, 0050.2013.0001.8 © Chancellor Patrick & Associates Pty Ltd; RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0001.27 © Lois Dixon-Ward; RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0001.16 © Lois DixonWard; PEA; RDA Gerald McCraith, 0050.2013.0021.20

© Lois Dixon-Ward; p. 101 (clockwise from top left) RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0001.9 © Lois Dixon-Ward; RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0001.22

© Lois Dixon-Ward; RDA unknown, 0050.2013.0013.1

© Dixon-Ward family; RDA Margund Sallowsky © RMIT University; RDA Gerald McCraith, 0003.2022.0002.6

© Lois Dixon-Ward

We acknowledge the people of the Woi wurrung and Boon wurrung language groups of the eastern Kulin Nations and respectfully acknowledge Ancestors and Elders, past and present.

Published by the Bowen Street Press 2024

Bowen Street Press

Building 9, Bowen Street

RMIT University, Melbourne, Victoria 3000

www.bowenstreetpress.com.au

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owners and the publisher.

The moral rights of the individual authors have been asserted.

Copyright 2024

© Text: Bowen Street Press and McCraith House residency recipients (individually credited) © Images: See Image Credits (page 102)

Part-title Captions

(pages 4–5) Perspectives of House at Dromana for G. McCraith, Esq., February 1955, architect David Chancellor (Chancellor & Patrick), RMIT Design Archives (pages 66–67) Aerial view of Dromana suburb and Mornington Peninsula coastline, 2019, iStock, tsvibrav

Production

Bowen Street Press

Publisher Tracy O’Shaughnessy

Managing Editor

Eugenie Baulch

Editorial and Production Team

Amaani Alikhan

Morgan Begg

Anna Carlsson

Izy Catrice

Lucy Grant

Ambriehl Khalil

Breanna Lancaster

Kit Russell

Katie Thomas

George Tzintzis

Sarah Wallis

Kristina Waterman

Printing

Printed and bound in Australia by Printgraphics

In 1955 Gerald and Nell McCraith commissioned renowned Melbourne modernist architect David Chancellor to design a beach house overlooking Safety Beach in Dromana. The Chancellor and Patrick design resulted in the remarkable ‘Butterfly House’ which is still an iconic architectural landmark on the Mornington Peninsula.

McCraith House was donated to RMIT University in 2013 by Gerald and Nell’s daughter Lois Dixon-Ward and her two daughters, Bin and Kerryn. The gift also included an archive of the house’s design, construction and use by the family which is held by the RMIT Design Archives.

The family donated their treasured family home with the desire to provide a space that invigorates both the mind and the senses. RMIT University then established a residency program to foster creative practice and research across all creative disciplines. Since 2013 the McCraith House residency program has inspired and galvanised more than 80 creative practitioners.

Cover design Christopher Black

Front cover image McCraith House ‘Larrakeyeah’ showing flowers blooming in the rockery garden created by Nell McCraith (RMIT Design Archives)

Back cover images (top) Original sketch by Chancellor & Patrick in 1955 (RMIT Design Archives); (middle and bottom) McCraith House refurbishment in 2015 by architect Peter Elliott (Peter Elliott Architecture & Urban Design)

Cover design Christopher Black

Front cover image McCraith House ‘Larrakeyeah’ showing flowers blooming in the rockery garden created by Nell McCraith (RMIT Design Archives)

Back cover images (top) Original sketch by Chancellor & Patrick in 1955 (RMIT Design Archives); (middle and bottom) McCraith House refurbishment in 2015 by architect Peter Elliott (Peter Elliott Architecture & Urban Design)