55 minute read

Dorothy Hunt (Brown), 1940, Alex

I attended The Royal Masonic School for Girls at Weybridge and then spent one term at the old Senior Masonic School situated close to Clapham Junction station. We transferred to the new school at Rickmansworth and I was present for the opening by Queen Mary in 1934. I was in Alexandra House. I became a prefect and later a Special School Prefect.

During Senior School, I received several prizes, including prizes for Writing, Fifth Form, Shorthand/Typing and Singing. I also received the Good Conduct prize, which was a Singer sewing machine!

Advertisement

A Happy Weekend

Chevalier Ruspini play

Catherine Ebdon (Lowe) 1941, Cumberland (written by her friend Margaret Bailey)

Catherine had only one term at Weybridge before joining Cumberland House. She was told later that in those days, when the girls were being allocated their houses, the brightest girls were sent to Cumberland House, and that was to be the standard to which all the other houses had to aim!

Catherine was born in Quebec in 1923 and came to England when she was eight years old. She entered the School in 1934. She had a very successful time there, becoming School Prefect and also Head Girl. She also won the silver medal for Good Conduct.

Whilst working as a Land Army Girl in the school kitchen garden, she developed hay fever and an allergic rash on her feet so she was hospitalised and placed in a wheelchair.

Land Army Girls

Because most of the domestic staff had left to do war work, the girls had to perform many chores around the building. The Sixth Form girls (there were only six of them at that time!) had to help clean the staff dining room in the mornings. This had the advantage that they were encouraged to eat any food which was left over after the teachers had finished – extra toast and marmalade etc. was very welcome during rationing times.

Catherine remembers being allowed to collect the sweet chestnuts when they were ripe. Eating them raw helped to fill the hunger gap. She also remembers Queen Mary’s visit to officially open the School in 1934 and practising her curtsy beforehand.

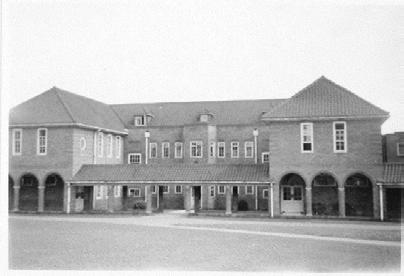

A School House

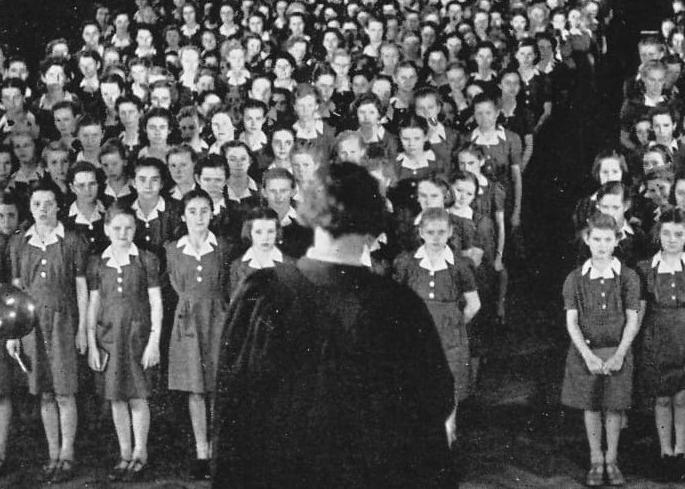

School Assembly

Heather Gibbs (Butcher) 1942, Cumberland

My first impression of Rickmansworth was getting ‘kitted out’. The material of the Victorian-style serge dress was so rough it irritated a tracheotomy scar on my throat so I ended up having to wear a cotton-wool collar. We also had combinations. We did not wear them in the proper style, like knickers, but like a pannier on the outside, making it look as if we had a bustle. Later we had liberty bodices.

I have always been most grateful for being taught to sew. Our first project was a shoe bag, second a pinafore, then we progressed to dresses for Greek dancing. We also did darning, for which I won a prize. This meant that I was given the task of mending holes for others.

My only memory of cookery is of burning rhubarb jam and spilling it. Once I was starting to work on a salmon for the governor’s lunch and a bluebottle flew out which turned me right off – even to this day!

Joy Williams (Liles) 1943, Ruspini

I began my studies at Rickmansworth in May 1938, towards the end of Miss Dean’s term of office as Headmistress. The Summer Term saw the 150th anniversary of the School; to celebrate, the Princess Royal, Princess Mary, made the awards on Prize Day. All the girls were given commemorative badges to mark the occasion.

As part of the celebration, there was a musical extravaganza performed on pianos by pupils. Eight instruments were placed on a dais beneath the balcony, with the younger children playing three to a piano and the middle school in pairs. The seniors played ensemble. It was a striking performance and has remained clear in my memory for decades.

Sports Day was held on the lower playing field with a band, and the cymbals were clashed every time someone landed in the jumping events. I took part in the flower pot and obstacle races, never having been particularly good at athletics. Prize winners received gifts such as tennis rackets, and for the novelty races, cameras and ‘Venus’ two-tier pencil cases.

Joy Liles, sitting opposite Ruspini House, 1940

Girls in hats in Chapel

At the outbreak of the war the Junior School from Weybridge moved into Ricky. Our domestic staff left for other duties so we girls had to take on their tasks. Each day after breakfast we performed these duties before getting ready for classes. Years later, watching Raiders of the Lost Ark, which was filmed at Ricky, I was amused to recognise the corner next to the stage which it had been my duty to keep sparkling.

One particularly vivid memory of the hostilities interrupting life at Rickmansworth is that of an enemy aircraft crashing on to a nearby hill. I was in the middle of a piano lesson when it was interrupted by the loud drone of an approaching plane. I just had a glimpse of it before my teacher, Miss East, threw me under the overhang of the piano, heroically placing herself on top of me as protection. Fortunately the airplane avoided the School. In true British stiff-upper-lip fashion, virtually nothing was said about the event afterwards.

All in all I had fantastic experiences and a superb education at the School, where I made lifelong friends. When I left it was to go on to the Denson Secretarial College, with further help from Ricky. I shall be forever grateful for the opportunities I was afforded at Rickmansworth.

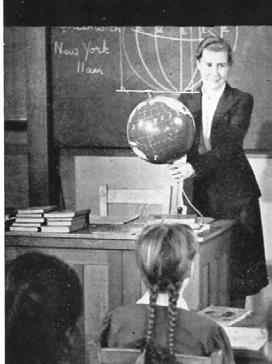

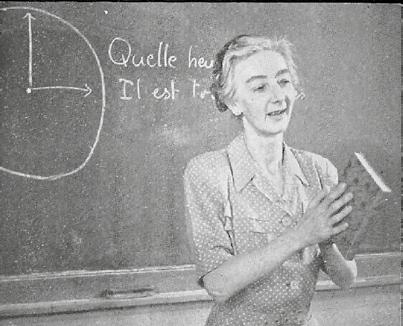

Geography Lesson with Miss Newnham

Jo Hall (Witt) 1943, Cumberland

School in Wartime

On 3 September 1939, when War was first declared, I was 13 and at home on my summer holidays. I had been at the School for just two years. We had listened to the wireless to hear Neville Chamberlain, the then Prime Minister, announce that we were at war with Germany. I can remember my mother’s reaction, which was one of horror that we should be at war again just over twenty years after the First World War had finished.

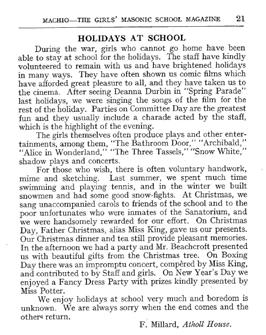

Holidays at School: Machio, 1941 After a few days my mother received a letter from the School saying we could go back there early where we would be comparatively safe and away from the towns where bombs might be dropped. I was not overjoyed at having my summer holiday curtailed when my mother decided that, since we lived in London, this would be the right thing to do. But after arriving at school, I quickly changed my mind. Not many parents had sent their girls back and we were about to have the time of our lives.

There was a skeleton staff who had volunteered to come back and look after us and we were delighted that they became more like friends than ‘govs’ (as we used to call them). We did not have to wear uniform. With minimum supervision we had the run of the School and we spent our time in the gym, the swimming pool and taking part in various activities such as races, play-acting, dancing and singing. We were given special food, not at all like the routine meals during school time. It was quite a wrench when the rest of the school returned and we had to conform again to discipline and school uniform.

School days were pretty routine and started with the ‘getting up’ bell at quarter to seven. This was followed by a dash to get to the washbasins as there were very few of them and we were only allowed two baths a week. When the war started, every bath had a green horizontal line painted under the taps and we were not allowed to fill the bath above this line in order to save water! From memory I think the depth was about six inches.

We then assembled in the common rooms in ‘decades’ where the prefects would make sure that we were all present. The Housemistress came in and informed us of any news or happenings for the day. We then trooped over to the dining hall for breakfast. This was preceded by a sung Grace after which, with a scraping of chairs and a loud babble of conversation, we sat down for breakfast. I can’t remember much of what was served up, except that we all seemed to eat an inordinate amount of bread which was very new and gave us indigestion.

House bathroom

After breakfast, each girl had to do a ‘duty’, which could consist of anything from doing a bit of dusting to making the bed and cleaning one of the mistress’s bedrooms. The latter was a coveted duty and I was lucky enough to do the room of Miss Jenkins, the Games mistress, on whom I later had a schoolgirl crush. Since as teenagers we were all awash with hormones, having a crush on a mistress or older girl was quite common. Also, being away from home and devoid of parental love, we had to find someone on whom to lavish our affection. It was all very innocent and mostly involved fetching and carrying for the object of one’s affection and the mistresses seemed to go along with it! We did not have much excitement in those days and we were away from home for three months at a time and only allowed one visit a term. Our treat of the week was being able to buy three pennyworth (no more) of sweets each Sunday morning.

Lessons took place from 9 o’clock until 12 noon, followed by lunch. When rationing came in our meals took on a more frugal form, although I can never remember being hungry. Dishes that remain in my mind are sultana roly-poly with brown sugar (spotted dick), tapioca (jelly babies) and Garibaldi biscuits (squashed flies)! We also had rather a lot of vegetable stews.

School Drill Lunch was followed by sports lessons, hockey, lacrosse and netball in the winter and tennis, swimming and rounders in the summer. Afternoon lessons started again at 3 o’clock. Tea was at 5 o’clock followed by a short period of free time before prep, which took place in the houses, then off to bed. Wednesday and Saturday afternoons were given over to sport and Saturday morning was the time for weekly ‘mending’. Our clothes were brought back from the laundry and we had to sit in the common room and repair any damage. I can remember using a wooden ‘mushroom’ to darn the holes in my lisle stockings. Our repairs were then inspected by a prefect and sent back if not done properly! All in all, it was a pretty regimented life.

I was at school for the first part of the war and life changed somewhat as there were already signs of it in the School when we returned. The staff and senior girls were involved in filling sandbags, although I can’t remember where they were used. We were also all issued with gas masks in case the Germans should use a gas attack, as had happened in the First World War. These had to be with us all day long, wherever we went, and it made quite a colourful spectacle as we had all bought different gas mask cases with shoulder straps to wear.

All the windows were criss-crossed with black tape which was designed to hold the glass together should there be any blast from a bomb. Blackout curtains were hung in the houses to prevent any light escaping to the advantage of enemy aircraft. A long zig-zag trench was dug behind Ruspini (now Alexandra) and Zetland houses. Inside the length of the trench, wooden slatted seating was installed and, at set intervals, there was an Elsan portable toilet. The idea was that, should a warning siren sound, we would all make our way in crocodiles to the trench.

Each girl had to knit a royal blue pixie hood for wearing on the way to the trench at night time. This involved knitting a metre-long scarf, folding it in half and stitching it together for about 20cm and thus producing a pixie hood which tied under the chin. In the event, while I was at school, there were only very few warning sirens in Hertfordshire, one of which heralded a land mine near Croxley Green.

However, the trench experience was not a happy one. Imagine four hundred girls and staff huddled together in a line sitting underground with a limited supply of air and only a few portable toilets. On one occasion this was compounded by the smell of kippers being served up for breakfast! It was not surprising, therefore, that the trench was abandoned after a while and we slept on mattresses laid end-to-end along the ground floor of each house. Being so close together, it was decided that we should sleep in face masks to avoid the transfer of germs!

Of course the war affected us in various ways. We all worried about our families who lived in threatened places, and many girls had brothers who were called up to fight in the war. It was a very unhappy time when occasionally a girl had to be told that her brother had been injured or killed.

I seem to remember we adopted a ship in the Merchant Navy, which was bringing food and supplies across the Atlantic. This was a very dangerous job as the ships were frequently being torpedoed by marauding German submarines. So we did a lot of knitting of scarves, balaclava helmets and gloves for the sailors. Some of us wrote letters to the men and, joy of joys, received the occasional letter back!

There were several happier events during that time which remain in my mind, one of which was the visit by the London Symphony Orchestra. I believe that the reason was because it was hard to find suitable and safe concert halls in London during the war and our main hall was considered suitable. It was a great occasion for members of the School Music Society, who were allowed to sit in the balcony for the whole concert.

Another vivid memory is of the days we helped out in the kitchen garden, the walled garden near the pond. To help the war effort we grew a lot of our own vegetables and I can remember sunny afternoons when we helped with the weeding. It was a job we enjoyed as we worked beside the handsome young male gardeners who would sing as they worked, stripped to the waist, turning our teenage insides upside down. After all, we did not have a chance to meet any male company as a rule!

I left school in 1943 to go to London University and so was thrust into the era of the V1 and V2 weapons which were unleashed upon London at that time.

1940s Girls

Sylvia Hedges (Bolt) 1944, Sussex (written by her son, Tom Hedges)

Like most of her cohort, Mum was partially orphaned. Her father, Leslie, died when she was three, leaving her mother and an elder brother, Norman, five years her senior. In the 1930s the prospects for the family looked bleak. Leslie Bolt had owned and run a shirt manufacturing business in Bristol, but had contracted tuberculosis. With his death, it was wound up with virtually no assets or money so his Masonic Lodge intervened and arranged for the two children to be schooled. Norman went to Bushey and Sylvia to Weybridge, aged seven. Later she arrived at Rickmansworth, to join ‘the orphans on the hill’, as the locals referred to the School.

These were the war years and she vividly remembers nights spent in the underground shelters with bombers overhead. There were many shortages, but the cooks always managed to produce good nutritious food, even if it was a little unusual to our tastes today. Much of it was based on bread and vegetables. Pots of jam and Marmite that arrived in parcels from home were seized upon with great joy. Other things were in short supply too and the white cotton napkins from the dining hall were repurposed as washable sanitary protection!

Sussex House Girls, 1941

My mother recalls her first impressions of Weybridge. She was issued a comprehensive school uniform: coat, hat, scarf, skirt, blouse, dress, sports kit, pants, socks and a peculiar garment that was a child’s version of a Victorian corset without bones but fastened with rubber buttons. All the girls struggled with this old-fashioned underwear.

She remembers her first night in the dorm, homesick and tearful, but this was made worse by the girl in the next bed who was wailing and crying so loudly that she made herself sick and was later removed to the Sanatorium. This girl was a sad little girl, her mother had died delivering her sister, the baby died too and her father was thought to have died from a broken heart. She and Sylvia became lifelong friends. It was a major feature at the School that all the girls had tragic backgrounds - most had lost at least their father and in several cases both parents. Everyone boarded.

When mum moved to ‘Ricky’ she joined Sussex House. On the ground floor were offices for the Matron and the Housemistress, plus a common room, mostly furnished with hard wooden chairs and tables and only a few comfy soft places to sit. Above, on the first floor, were four dorms of ten beds with toilets, basins and a bathroom with just four baths that everyone had to share. The staff had two bedrooms to themselves and on the top floor in the eaves lived the domestic staff, who were called ‘maids’. These women worked in the kitchens, the laundry or as cleaners.

Special f Special Friends, 1941

Most afternoons were dominated by sport outside on the playing fields, where lacrosse, hockey, netball, tennis, and athletics were played. The swimming pool and gymnasium were also used. Mum was taught to swim and to dive ‘properly’. We used to pull her leg every time she dived into a swimming pool as she would line herself up, toes just gripping the edge, arms composed and swung smartly up, over and together, as she jumped up to do a classic dive, entering the water without a splash. She must have been drilled for hours to achieve this and it never left her. Dad would shout, ‘You’re not at school now!’

Lessons finished at 4 o’clock and were followed by prep (homework) before tea in the dining hall at half past five, then back to Sussex House for a second hour of prep, before you got some time to yourself. Girls would read books, or comics, play board games like Monopoly, chess, or draughts, or would knit. During the war years everyone was given wool to knit hats and scarves to combat the cold as the heating was turned down to save fuel. The choice was: knit warm clothes for yourself or freeze. Bed was at half past eight with lights out at 9 o’clock.

On the outbreak of war in 1939 the shelters were dug and opened, but they were not used very much. Early on when the sirens announced an air raid, the girls were marshalled into the shelters, but they were damp and uncomfortable. It was almost impossible to sleep. They then had problems the next day with both the girls and staff falling asleep in lessons. Using the shelters was soon abandoned and replaced with a well-rehearsed drill whereby, when the siren sounded, you took your mattress and bedclothes downstairs from your dorm and all crowded together on the floor of the common room.

You arrived at the beginning of term and never left until term end. During the war, when petrol was rationed, everyone arrived by train and walked the mile and a half up to school from the station. In Mum’s case the journey started in Bristol at Temple Meads Station, where three or four girls from the school met with their mothers to board the train for Paddington. They would be settled into a compartment and put into the care of the guard and then their mothers went home. The crossing of London was a great adventure. They would, if early, skive off to a cinema or a Lyons Corner House before getting the last possible train to get them to school on time. Mum tells of the delight to be naughty. They relied on being given a shilling or two of pocket money from aunts and uncles to fund these jolly japes. Their luggage was always forwarded by Carter Patterson, a haulage firm, so at least they only had a small bag with them.

Just once each term were their families allowed to visit on a Saturday afternoon for two hours. Tea and biscuits were provided but other than that you just walked round the grounds and then when the bell went, you went back to your house and your mothers were sent home again.

My mother did not get many visits from her mother, as it was a long way to come from Bristol for a two-hour visit, but she did have an aunt and uncle who lived in Uxbridge, who would visit. They were the source of pocket money for japes at the end of term on the journey home.

Saturday morning was when the girls would repair their clothes, darning socks and stockings. Clothes had to last. The girls amused themselves wandering around the grounds and playing in the pond. In the afternoon it was matches against other local schools and you either played in the team or stood on the side-lines and cheered.

Sunday was Chapel for both a morning and evening service. These services were mainly conducted by the Head but once a month the local vicar or curate would come to the School and those who were confirmed would take communion.

Vegetables were not rationed but you had what was available. You certainly did not have imported bananas, they disappeared and did not return to the shelves until 1945. The School had a large kitchen garden and the girls helped to grow veg that was used in the kitchen. Produce was pickled to preserve it or salted or carefully stored so as to extend its life.

Bread was never rationed but was in short supply. If there was some left-over it was distributed to the girls’ dorms just before bed (and invariably it was stale, but when you were hungry you ate it anyway). The prefects were given privileges and at Saturday tea they were given some bread, a scrape of marge and Marmite plus a bun, and the Table Prefect was served baked beans on toast and took forever to eat this delicacy in front of the envious girls. Now you understand why a piece of stale bread at bedtime was scoffed down. To A Geometry Text-Book: Machio, 1942

Elsie Houston (Biggs) 1944, Cumberland

D Day Remembered – June 1944

Half term had just ended on my last term at school. I was House Prefect in Cumberland and responsible for the behaviour in my dormitory. The usual restlessness increased as the first planes went over. Excitement rose as it became obvious that a big raid was starting. Naturally the edges of the blackouts were lifted to peep. After allowing for reasonable curiosity I told the girls to get back into bed. Jean Sinclair suggested that my future husband might be in one of those planes. After the laughter subsided, I managed to settle them and fortunately no teacher arrived to complain.

The next morning after breakfast I was checking that all the ‘duties’ had been done properly, when an excited Sheila Whittington informed me that D Day had come. I guessed that meant the Second Front had started but I had never heard the term D Day before.

I felt a mixture of thankfulness and fear. It had to be a success first time or the cost would be tremendous. My elder brother Charlie had been killed in Tunisia. My brother Alec was on the Destroyer Quorn based at Harwich so I knew he was involved. Miss Fryer suggested that Morning Prayers would be held in the chapel for the rest of the week. A box was provided for special requests for prayers.

A few days later, the sirens went. We had been fortunate: the School had escaped the bombing and alerts were rare by 1944. This was our first experience of doodlebugs. Everyone had to dive under the nearest table as there would be no time to reach proper shelter. For a few days the alerts were frequent but they did not last long.

My brother had leave from the Navy and visited me on 15th July. When he left, I watched from the upstairs window until his cap could no longer be seen. I left school on 27th July. On Tuesday 8th August a letter arrived from my mother who had received the dreaded telegram informing her that Alec had been killed. Finally Miss Fryer wrote and informed me that although I had failed my oral French, I had obtained my Highers.

Patricia Whelpton (Surman) 1944, Alex

I was still at Rickmansworth at the beginning of the war and remember air-raid practices when we descended into the underground shelter in the grounds, which had been dug out specially.

When the siren went we used to go to the air-raid shelter but it was bound to be too damp. Then we used to congregate in the boarding house. Many staff had left to join the forces, so we were allotted ‘chores’ to do, such as cleaning the tables in the dining hall and ‘helping’ in the kitchen. I had to dust Miss Verity’s room each day.

We had lots of sport to enjoy after class: swimming in the pool, tennis, netball, hockey, lacrosse and competitions between the houses. We also had girls sharing our facilities; they were evacuees from London but they didn’t ‘live in’.

The doodlebug period was one of the worst. As I was nearing school leaving age, I understood the danger more than before.

We were given clothing coupons and were kitted out when we left. I had a super chocolate-brown bouclé coat which I used for donkey’s years! We made lots of friends which lasted for years after leaving school. Patricia Surman and Margaret Davies, 1941/42

Joan Wingfield (Courtney) 1945, Moira

The War Years 1940-1945

The Spring Term began in early January. This was also the beginning of the school year when the forms moved up to start a full year’s syllabus. The School Certificate Exam was traditionally taken at the end of the Autumn Term. It took several years to alter this to the more acceptable Summer Term.

By now we were all familiar with the blackout routine, with blinds on the windows and curtains in front of the doors. Assembly began the next morning and lessons proceeded as normal in our new classrooms. We were surprised to learn that our Headmistress, Miss Calway, had left the School and had married the curate from the village church. She had only been in the post for a year and it was another year before Miss Fryer replaced her. Meanwhile, Miss Potter, our Latin teacher and Deputy Head, was in full charge. Joan Courtney and friends

Each house had 15 children and a staff member from the Weybridge School evacuated to it. The children aged seven to ten had one of the four dormitories, the senior girls were in the other three. We had to keep our garden coats, pixie hoods, gas masks and shoes close to our beds in case the air-raid sirens sounded. The Rickmansworth siren wailed up and down but Croxley Green had an unearthly and quite scary noise. When the sirens sounded at night, we had to dress over our pyjamas and stand in line until we filed downstairs to be escorted to the trenches. We sat on wooden benches with dim overhead lights until we heard the ‘all clear’ and returned to bed. The sirens sometimes sounded at breakfast time and we went to the trenches with our plates.

Rules were strict and some areas out of bounds as all pupils had to be accounted for in case of an air raid. We carried our gas masks everywhere at this stage. We followed the course of the war with maps and newspapers but until the bombing raids became intense in the autumn of 1940, it all seemed a long way away.

Returning to school in September 1940, we were relieved to find the trenches closed and other arrangements made for our safety at night. We got ready for bed upstairs in our dormitories then went downstairs where our mattresses, pillows and blankets were placed end-to-end, the length of the corridor in the centre of the house. We slept head-to-toe, two to each mattress. During the day the mattresses were piled up in the cloakrooms.

Owing to more crowded conditions it was easy for epidemics to take hold. Chickenpox started in October, followed by a more serious bout of scarlet fever. About twenty or thirty girls spent Christmas in the Sanatorium. The start of the Spring Term 1941 was delayed by three weeks so that pupils could return to school in good health. Unfortunately measles was soon going around.

Some girls lived in cities targeted for constant air raids, so one of the school houses remained open for several holidays so that they could stay in safety. Volunteer members of staff looked after them; by all accounts it was great fun. Frequent visitors were Lord and Lady Harris, who arranged outings and treats with great kindness.

We were able to sleep in our dormitories again as, although there were air raids, Rickmansworth was not on the flight path to major targets. School life continued normally but the news was important to us as we grew older.

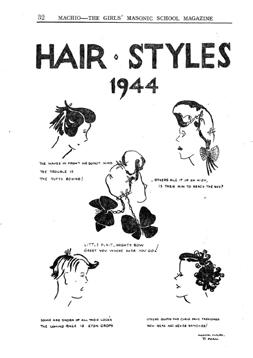

Hair Styles by Margery Scales: Machio, 1944

We plotted army positions on maps and had access to daily papers. We listened to all Churchill’s speeches to the nation and though they were grave, we felt confident. The war came nearer to us at times, older brothers were in the services and in danger. The bombing of Pearl Harbor and the arrival of American troops in England gave us cause for optimism.

During 1942 the Head Matron, Miss Lane, retired and was succeeded by Mrs Wade, a popular matron from Weybridge. She modernised all our school underwear and earned our undying thanks. Owing to the introduction of double summertime, we hardly saw darkness in the Summer Terms. We looked forward to Sports Day, Prize Day, Old Girls Day and a holiday on Empire Day, the flag flying on the Clock Tower. The School adopted a ship from the Merchant Navy. Senior girls kept contact with captain and crew. The war came much nearer home to us when the pilotless planes were launched from the continent, aimed at London and Kent, but coming down at random. We were told to get under our desks if we heard the strange throbbing noise. More scary was the launching of the V2 rockets that gave no indication of their presence until they landed. Some girls on leaving school joined one of the services as a new career had opened for them.

Left to right: Sheila Low, Margery Scales, Brenda Elliott, Joan Courtney

The war was coming to a conclusion by the beginning of the Summer Term, 1945. When we were finally told that the war was over it was hard to believe. There was an enormous bonfire beyond the lacrosse pitch where everyone gathered, shouting, laughing and singing until we had no voices left. Some of us had spent the entire war being educated and protected by the Masonic School.

Sheila Side (Whittington) 1945, Cumberland

I remember Saturday night feasts with candles; the boredom of Sundays, learning scripture verses but wishing I was at home. We weren’t really allowed out because it was war time and so my friend and I decided to join the Girl Guides for the sole reason we would get to go camping. Unfortunately, after we signed up we were informed that there was to be no camping because of the war. So that was it, we resigned there and then!

In the Sixth Form we were allowed into town on a Saturday afternoon to do a bit of shopping. Sometimes we were taken to concerts in the Watford Town Hall.

I wasn’t academically minded, but I could have taken up drawing professionally. Unfortunately in those days you didn’t do Art as a profession – you either went in for teaching, nursing or secretarial work.

The Boredom of Sundays by Sheila Whittington

Life in the Dorm

Saturday evenings in the common room, you had to make your own entertainment, as there wasn’t TV or radio. There was a piano so we would make up plays. We all had to play the piano for a while. We were very lucky with the music teachers.

One term, I brought back a pound pot of strawberry jam. I don’t know how I thought I was going to eat it, but one morning, our Housemistress said she was going to inspect all the lockers.

Friends: (left to right): Roslyn, Whitty, Staple, Hoppy, Betty, Ces

Well, I had my contraband pot of jam in my locker and I thought ‘what am I going to do?’ So during recess I crept back to the house and got my precious jam from my locker. I went upstairs to my dorm and hid under my bed, behind the counterpane so that I couldn’t be seen. Then I proceeded to eat the whole jar as fast as I could to destroy the evidence. Well, I have never felt so sick in my life and to this day I cannot stomach strawberries of any description. I think back to that time and wonder why I didn’t just throw it out of the window. But of course it was war time and so I couldn’t possibly have wasted it like that!

Our lockers were in layers of three, about 2ft by 2ft for all your possessions. One holiday I thought I would create a museum and spent days collecting animal paws, bits of fur and nails, anything that I could find outside. I then had this wonderful museum collection which came back to school with me and took pride of place in my locker. One day when we were in class, Matron went around inspecting the lockers. She found my museum collection which wasn’t supposed to be in there, and threw it away. Imagine my dismay when I found out that the museum I had painstakingly collated had disappeared. Oh, I wasn’t happy!

I was a House Mother for a few years, and had one child to look after. It was a very big place for a small child of eight to find their way around. It was a wonder they didn’t get more lost or more homesick. We had to plait their hair in the morning. Everyone learned to muck in.

We were well looked after but didn’t appreciate it at the time. We had surgeons who were the Queen’s surgeons. It was a beautifully equipped surgery with one room for nose paint and another for sore throats. One of my friends had all her toenails taken off – I think back and wonder what on earth she could have had wrong with her toenails.

1938 letter home

Dear Mummy

Thank you for your letter. The whole school went to see Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. We have gone into our winter frocks. They are nearly the same as our summer frocks except they have long sleeves. We are going to have fire drill in the middle of the night. Would you mind sending me a card of clips for my hair? We have sweets every Saturday. We have had our eyes tested and been to the dentist. I have just heard that there is not going to be a war.

We had fire drill last night and I was half asleep and half not.

Love from Sheila x

Food

The war-time food was very stodgy. We always had bread for tea. Three pieces of round bread with a little pat of butter or marge. If we wanted more we had to put our fingers up and they would come round and count our fingers. I had a little house child to look after and I used to say to her, ‘Put your fingers up to get more bread for me’.

Sheila Whittington and friends

VE Day Bonfire: Machio 1945

End of the War

There were rumours that the war was about to end. It was Prize Day and we were going to do School Drill in front of the Committee and visitors. The news was coming through that the announcement of the end of the war was due at any minute. The gardeners were placed by each door in the Great Hall and they each had a walkie talkie; if the news came through that the war had ended they were to signal to Miss Fryer up on the platform and she was going to stop the proceedings and tell us.

It wasn’t actually until the next day that it happened, but there was a feeling that it was going to happen at any moment. When the announcement finally came through, we all went mad but we weren’t allowed home. Luckily for me, my mother was allowed to come and visit because she only lived in Watford and that was a great thrill.

Later on we had a bonfire and danced around it. Hoppy (Rosemary Prosser) and I (silly children that we were) wanted to do something daring so we announced that we were going to climb on the roof of Cumberland House. We were really up for doing it until some spoilsport said if we did it and were caught, the whole school would be punished. So that made us stop and think and decide not to do it.

I left school the term when the war ended. I literally began school in the September when the war started and left in the summer it ended.

On reflection it was good training, although it was a bit severe and I couldn’t imagine my children, or certainly not my grandchildren, putting up with it. But on the whole I can honestly say I was quite happy – I mean there were moments when I was terribly homesick as was everybody. But you made good friends, and something that I learnt was that you had to get on with a person, even if you hated them you had to get on with them. It was very good training, even in an office there’s always someone you don’t like but you had to jolly well get on with them. It was a good upbringing.

Rosemary Matthews (Prosser) 1945, Cumberland

The first year of the war was relatively quiet. We had several air-raid drills where we practised going to the shelters which had been built on the edge of the school grounds – well underground. We had to be very careful with our water supply because they were going to need the water if there were ever any fires in London. So we had a line painted on our baths and we were only allowed three inches of water in our baths, no more. All our windows were blacked out with dark curtains so no light could escape, and if there was ever an air raid then the planes wouldn’t be able to see us.

Then, in 1940, we started having air raids in London and although we didn’t experience any over our school, we could hear them because London was only 20 miles away. We could hear the bombs dropping. If we peeped out from underneath the blackout curtains in our dorm (all of our beds were around the edges of the wall of the dorm, and you had a window practically by every bed) we could see the red sky at night and in the morning we could see the black smoke from the bomb damage.

We could hear all the planes going overhead to do the night bombing in Germany. And if you peeked out from underneath the blackouts, you could see the shadow of the planes. There were great droves of them against the night sky. Then sometimes in the morning you would wake up at dawn, 4 or 5 o’clock, when the sky was getting light, and you would see them coming back in ones or twos instead of those great big formations that they went out in.

Soon the air-raid siren would sound to say that the planes were in from Germany. We’d have to get up and trundle over to the shelters, which were down the steps, and into the long narrow spaces with wooden benches and bathrooms here and there. You would sit on these benches and see the condensation falling down the walls from all our breath. And the little ones would lie on these benches with their heads on the laps of the seniors. When the ‘all clear’ sounded, we would go back to the dorm.

Then maybe two hours later the air-raid siren would sound again. This would go on and on and was ridiculous because we weren’t getting any sleep. So we stopped using the shelters and used the middle corridor at each boarding house instead. The windows were at the very ends of the building so if there was flying glass we wouldn’t be hurt. And at least we could stay in bed, and just hope that the School wouldn’t be bombed, which it wasn’t.

We adopted a merchant ship and were all asked to knit things. Of course, I couldn’t knit – only plain and pearl, but a friend of mine decided we would at least knit a 6ft scarf. Some of the girls were marvellous and knitted balaclava helmets, big gloves and huge sweaters. But my friend Whitty and I were knitting this huge scarf very laboriously. We would look at it every day and see that it was only growing a bit so we used to stretch it, and of course by the time we finished it, it had a waist because of all the pulling! But at least we managed to make something.

Sports Day Programme, 1941

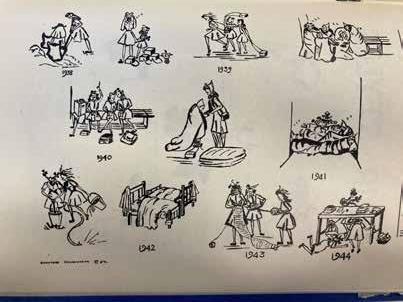

RMS Life in the 1940s, by Dorothea Holdsworth: Machio,1944

Then the war went in our favour and to a large extent the raids over London stopped. However, we began to get the doodlebugs. They had a definite chugging noise when they went overhead, and if that noise stopped you knew it was going to drop. Once, we were in the middle of our exams and I remember hearing this chugging and the teacher at the front of the class shouted ‘under your desks’. We’d been taught to do this in practice, so we flew under our desks and had to keep our tummies off the ground, fingers in our eyes and our thumbs in our ears. I remember diving under the desk and thinking ‘Will I ever see my mother again? Will I ever see the dog again? Will I ever get back home again?’ But anyway, it didn’t fall near the School!

Life went on quite normally for a school really, other than the fact that you couldn’t go out anywhere and do things. And the teachers were wonderful, you never got the feeling that they were frightened. It was amazing really when you think about it.

The day the war ended we all brought out our flags and ribbons in red, white and blue that we had been stashing in our lockers. And since we no longer had to use blackout curtains any more, there was a huge bonfire and great festivities. And that was the end of that.

Speech by Lady Leese on Prize Day 1945

1946 Girls

Jane Sharrock (Chappell) 1946, Ruspini

I remember going down to the trench with a pillow and blanket. And returning back to the School when the ‘all clear’ was sounded. I stayed at school during the Christmas holidays – Father Christmas came (one of the Americans stationed in the village). We all had a present – mine was a paintbox and I took it up to the Art Room and drew a pig which I painted pink with black spots! Uncle Bob, who was in the Navy, came to see me. I was allowed to go out with him but had to be back in time for school prayers. He took me to a very smart restaurant in the Strand and when we were there he said I could take my school hat off, but not me! I thought my hair would be in such a mess!

Margaret Weston (Naismith) 1948

During the Second World War, many schools adopted various ships in the Merchant Navy. In 1947 the British Ship Adoption Society wrote to Miss Fryer asking if a pupil could give the Christmas Message to all seafarers. I felt very honoured to be chosen to represent RMS and many other schools.

After a number of practices the day arrived to go up to the BBC with Miss Newnham. We had one run-through before going on air. The broadcast actually went out on December 26th in 1947. Here is the script of the broadcast:

‘Greetings to all Merchant Ships, wherever you may be, from all the boys and girls at home. We know that, but for you, we could not have enjoyed many of the good things which still help us look forward to Christmas, and we realise that you must spend it away from your own families in carrying out your daily watches. I hope you spent a happy Christmas, as we did.

There are many thousands of boys and girls who, like me, have their own adopted ship and have come to learn more of your work and life. We wait for your letters eagerly and they help us when we try to learn more of other people and places that keep our ships trading all over the world. We shall remember, long after our schooldays are over, our friendship with you and all you do to help us in our studies.

My Daddy was in the Merchant Navy and I am so proud to send you this message of good wishes from your young friends all over the country.

May the New Year bring you fair winds, safe voyaging and happy reunions with your families.

Are you listening, Ocean Courier? Are you listening, Captain Craston? Your school sends you special greetings. Are you listening, our Belgian ship, Prince de Liege? Un bon Noel! To the big ships and the small ships, to all our Merchant Navy, thank you and God speed you on your voyages.’

Correspondence to Ocean Courier, signed by the girls

Brenda Barnes (Issitt) 1949, Sussex

September 1940

The day before I set off for boarding school, for a special treat, I chose to visit London Zoo to see Ming, a baby panda recently born there. A photograph taken on that day shows me in Regents Park with my new cuddly toy ‘Ming’, who accompanied me to Rickmansworth every term and is still treasured in the family.

My mother and I travelled from Dulwich by tram, bus and train and then took a taxi up to the new school buildings just six years old, with very impressive iron entrance gates, painted blue and gold. The Lodge Keeper came out and, after checking our papers, directed us up the long tree-lined drive. We entered a vast building to be greeted by Miss Mildred Harrop, Weybridge Head, as the Junior School was now evacuated to Rickmansworth for the duration of World War II and Miss Mabel Potter, acting Head of the Senior School, as Miss Bertha Dean had retired and Miss Fryer was yet to be appointed.

Swimming in the school pool

We moved through to the Sanatorium for a full medical check, before meeting the other new girls. The Bruce Twins, Elizabeth and Felicity from Hampstead, clutching bright yellow gas mask cases, and Sheila Nesbitt from Chiswick. As seven-year-olds we were the four youngest girls in the school. The air-raid siren sounded, so Sister told us to say goodbye to our mothers and hustled us down to the trenches. Being petrified at the sight of so many girls in an underground tunnel, I screamed loudly, hoping Mummy would hear and rescue me!

We were allocated to Moira, nicknamed the Baby House, with House Mothers to guide us. Our classroom was the gym changing room, very grey and without windows, where we had a morning routine of Elocution to rid us of any regional accents, Reading, which progressed at the pace of the slowest girl, and Writing between three lines. In the afternoon we returned to the dormitory to rest on our beds. I was bored, unhappy and cried continuously, so my mother was not allowed to visit at half term as ‘I had not settled into boarding school life’.

Actually this punishment did me a favour, as Miss East, Housemistress and Head of Music in the Senior School, looked into the common room and, seeing I was the only child there, hugging the radiator and looking sad, invited me to warm up in front of her sitting-room fire and tell me all about my previous school. From what I related she realised I was an outdoor girl, an avid reader and very musical and sympathised with my homesickness, as she too had been a Masonic Girl. She very kindly found me books by my favourite authors and introduced me to Miss Ormerod, Junior School Music teacher who put my name down for piano lessons and told me to come along to Percussion Band. At last boarding school was looking more interesting. Brenda Issitt in 1940

Most nights there were air raids, so we had to leave our beds, put on warm outdoor clothes and walk quickly to the trenches, each house having its own entrance. After hot cocoa and an oatmeal cake we settled down on the narrow twelve-inch benches and, wrapped in a blanket, tried to sleep. Later on, when the raids were not so severe, our beds were moved from the dormitories to the corridors and we only went to the trenches when the action was overhead. A bomb did drop in the Garth, but luckily everyone kept safe.

Heating was minimal, so we were issued with wool combinations to wear next to our skin and taught to fling our arms around our bodies like windmills if we felt shivery.

Food rationing meant a limited menu with no choice: breakfast was either a rasher of streaky bacon, a fish fillet or an egg followed by as much bread as you liked, but only one butter or margarine pat allowed. As a special treat each girl had a chipolata sausage on Sundays. Midday dinner was a meat or fish dish with plenty of vegetables from the kitchen garden, maybe macaroni cheese or bean stew. Your plate had to be cleared completely before you were allowed pudding. Puddings were substantial, made with suet, pastry or a sponge mixture. Tea was back to bread, spread with Marmite, fish paste, peanut butter or National Orange Juice jam, produced by the Ministry of Food from rosehips. Cake was only served on Committee Days.

Dining Hall

Once a month the House Committee visited the School to check all was well, and came into the dining hall to cut the large fruit cake into slices and chat to us individually. We had apples, pears and figs when in season from the orchard and every year Lord Harris, a member of the Committee, brought baskets of cherries into Tea.

Infections were rife. I succumbed to chickenpox, measles and mumps, but did not catch influenza when it hit most pupils and staff. Houses had to be turned into sick bays and the healthy ones confined to one boarding house where, much to our disgust, we carried on with our normal routine wearing face masks. But of course we felt relieved in the end, as the sick girls had a large amount of school work to catch up on in their free time.

School routine

After breakfast every girl had to do a household chore. My first job was to breathe hard on the lower panes of glass in the hall doors and then polish the glass until it shone, whilst my last task was to get the stools down from the chemistry lab benches and get out the apparatus ready for the first class of the day.

Morning assembly was at 9 o’clock followed by two forty-minute lessons, then back to our houses for a glass of milk, collect post from home and to remake our beds if the sheets were not taut enough or the hospital corners not neat enough for Matron’s liking. Back to the classrooms for more lessons until midday, when you played sport or had free time until lunch hour.

After lunch it was games sessions for those who’d had free time before lunch and free time for the others. Afternoon school, 3 o’clock until 5 o’clock, consisted of two-hour sessions for Science subjects, Art, Needlework, Handicrafts and Domestic Science. Music lessons were given during the afternoon. School Drill practice took place in the Hall at noon on Tuesdays, compulsory for all, with those too young practising the exercises and learning the correct way to march in the Gym.

Most evenings were free to join Brownie or Guide activities or practice in the Music Rooms, whilst Seniors did preparation (homework) in the Senior Common Room. The School had adopted a Merchant Navy ship, so we were all taught to knit scarves, socks or jumpers for the sailors in very thick grey wool, which they told us in newsletters were very much appreciated.

Eventually younger girls replaced us in the ‘Baby House’ and I moved into ‘Sussex’. Every morning we had to pass ‘muster’ before being allowed to leave the house for breakfast. This meant being clean and tidy in every respect from our heads to our toes. We now had freedom to climb trees in the Dell, swing across it on ropes securely placed there by the gardeners, or have bow and arrow battles with other gangs, making sure we did not damage ourselves or our uniforms! We were allowed to grow salad crops in small plots behind the pond to supplement our diet and playing in this area whilst watching pond life was an interesting pastime.

Nicknames were popular for people and food — Yorkshire pudding was known as bathmat, milk puddings as frogspawn — friends were Deadley Leadley, Podge Page and Doggie Barker, and I was known as Tubby Isitt, which speaks for itself! Around our houses we played hopscotch in the Cloisters, skipping on the gravel area and conker matches. Indoors there was always a game of Monopoly taking place, new players joining in when existing ones were called away, returning to find your fortunes lost or made. We also enjoyed practising extracts from plays such as Pinocchio to perform to our mothers at half-term visits.

Miss East continued to take an interest in my music career and I found myself taking part in the music programme every Prize Day. Firstly in Junior School, opening the proceedings by marching in as a member of the Percussion Band, playing triangle and then tambourine. Then in Senior School, playing on eight Broadwood pianos arranged in an arc. Firstly in the Trio, later followed by Duets and then finally Duo. After passing several piano exams I was also chosen with other girls to play Duets when the girls marched out of Assembly.

V E Day

At last war in Europe ceased and 8th May 1945 was declared a Public Holiday. This meant a whole day to spend as we wished, apart from a grand picnic behind the boarding houses in the afternoon and a bonfire on the lower playing field once it was dark. It turned out to be a day of mixed emotions, most girls happy that air raids had ended and we no longer had to carry gas masks, whilst others were sad to realise that fathers and brothers would never come home again. During the summer holidays, on 15th August, war in Japan ceased, so more celebrations as my Aunt, who had been stranded in India since 1937, was at last able to get on a ship bound for England and my Uncle was demobbed from the Army.

Slowly life at Rickmansworth became less restrictive. We were now allowed to visit the village in pairs. This consisted of St. Mary’s Church, Chequer’s Tea Rooms, Woolworths, W. H. Smiths, the Post Office, butchers, greengrocer and a baker. Weekend walks in groups were also allowed along Chorleywood Road, where people had started building their own houses, and we were able to put to rest the idea that we were all orphans on the hill. The Guides were allowed to camp outside the school grounds and visits to places of interest in London were arranged.

King George VI and Queen Elizabeth visited the school and Princess Marina, Duchess of Kent, came on Sports Day to present the prizes and cups. I was lucky enough to win a flat race that day, so as she presented me with a box of Dunlop tennis balls, I discovered she spoke English with a very strong accent.

In January 1947, we received letters to say that we could not return to school on the due date as the snow, which had been falling since Christmas Day, and icy conditions, meant the School was frozen up. When we returned, sports were impossible as the ‘Big Freeze’ lasted until March, so instead we all became experts in snow clearing to enable walks around the grounds to take place.

1949 was my last full year at Rickmansworth and the only choices of career were nurse, teacher or secretary. Having attained a good Cambridge School Certificate, I decided on a career as an English teacher. Working alone in the Sixth Form, studying a complete Bernard Shaw and Shakespeare plus a complicated Grammar book, with only forty minutes tuition a day, as well as being in charge of classes when teachers were absent, was bearable for only one term. In January 1950 I started work at the Midland Bank Head Office in the City, the start of a lifetime career in finance. I was glad to be living permanently at home for the first time since 1939.

On reflection, I was extremely lucky to be taken under the wing of my father’s Lodge when he died in 1934 and my mother was left with nothing but a ten shilling (fifty pence) weekly allowance from the State. The Masons paid for me to attend an excellent preparatory school from the age of four to enable my mother to start a career in the Civil Service. Each holiday I had to visit my Masonic Guardian to show him my report and get his comments, which were usually good enough to merit holiday pocket money.

Girls walking past a school building

Vera Hughes (James) 1954, Moira

Wartime at school was very different from wartime at home. No bombs, or guns, until the doodlebugs started coming over after D Day in 1944. These bombs could fly far enough to reach Hertfordshire, although there was little to bomb in the countryside. I certainly heard them flying over us, hoping they would keep going. Their sound was like the chug of a motorbike on half throttle. You started to worry when they went quiet — it was an eerie, threatening silence — because that is the point when they would drop.

We did have some big shelters in the grounds, but we only had to go there a couple of times when the doodlebugs started. Otherwise, if the siren went, we returned to our houses and waited until the ‘all clear’ sounded. I was very indignant when we had to leave our half-eaten macaroni cheese one dinner time. When we were able to return to the dining hall the maids had cleared it all away.

We did not go hungry. Breakfast was cereal, bread, marmalade and sometimes porridge. Tea was poured out of an urn. There was always sugar in the middle of the table, but when you were small you had to ask for it, which was a bit daunting as the bigger girls were all around you. I finally gave up sugar in tea as being too difficult. We could ask for a ‘small’ if we really didn’t like something but were never allowed to leave any food. Butter beans at dinner times were a challenge, but could be swallowed quickly with a lot of gravy.

Dinner was a main course brought to the table and served by the prefect, followed by pudding. This was sometimes milk pudding, like tapioca and semolina, or bread pudding. There was a mistress overseeing the meal; Miss Robinson was obsessed with the necessity of eating your pudding with a fork — try it with tapioca!

Tea consisted of bread, butter and usually jam, but I do remember one day it was just sugar. You just ate as much as you could manage in the half hour allowed; I still eat very fast. We stood at the beginning and end of the meal to sing Grace, accompanied by a girl (including me) at the grand piano in the dining hall.

All four hundred of us were without a father, the men having been killed in the war. There were exceptions for girls whose fathers, always Freemasons, had perhaps physical misfortunes. My friend Margaret’s father was blind. I don’t remember ever talking about our fathers and we saw very few men: the doctor, the dentist, the local vicar, a young curate if we were lucky, and a couple of gardeners.

Once a month we had cake for tea, as well as the bread, butter and jam. The ‘Committee’ came and cut the cake at the table after their monthly meeting and we had to ‘entertain’ them after evening prayers.

Apart from certain restrictions — being confined to the School grounds, letters abroad having to be written on special airmail paper and censored, certain foods being unobtainable — the war at school had little impact on me. I do remember having to go potato picking; some of the grounds were cultivated for growing vegetables and we helped with the potato harvest.

I was nine when the war ended in 1945. Great celebrations of course, but we stayed in school. In fact, life went on much the same as it had done before and during the war.