Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

Concepts to Improve Water Quality and Flooding

Charleston, South Carolina

June 2023

Photo Credit: Lindsey Shorter

Gadsden Creek

Photo Credit: Lindsey Shorter

Gadsden Creek

The Charleston community is contemplating the future of Gadsden Creek. While cities around the world are working to clean up polluted waterways and resurrect buried streams, Charleston is considering paving over one of its last remaining urban tidal creeks to make way for new parking garages and condos.

In the 1950’s and 60’s, the City of Charleston filled much of Gadsden Creek’s salt marsh with municipal waste and ditched and straightened its tidal channel. Like countless other urban waterways in the United States, the rapid growth following World War II was devastating to Gadsden Creek—and to the Gadsden Green community that had lived alongside and cherished the creek for many years. Gadsden Creek stood in the way of “progress”.

The landfill was closed in the early 1970’s and the creek has been recovering ever since. Gadsden Creek now supports a thriving ecosystem and is one of the few remaining places in historic Charleston where a community of oysters, egrets, crabs, shrimp, marsh wrens, snails, cordgrass, and other salt marsh species can be found. While the infrastructure around Gadsden Creek has deteriorated, the creek itself has exhibited a tremendous capacity for recovery. Gadsden Creek is resilient and far older than any live oak tree, Charleston single house, or cobblestone street. Gadsden Creek has surpassed them all—and it continues to live and support life.

During large tides, the roads and buildings that were constructed on top of the filled-in marsh are flooded with the waters of the Ashley River. These areas flood because they were built on top of a marsh; marshes are meant to flood. The flooding problems associated with Gadsden Creek are humanmade problems. And although the City of Charleston has spent hundreds of millions of dollars on flood reduction projects around the peninsula, very little has been done to lessen the effects of flooding in the Gadsden Green community. Furthermore, Gadsden Creek is threatened by polluted urban stormwater runoff and leachate from the adjacent former landfill.

These concerns over flooding and pollution are not unique to Gadsden Creek. Urban streams have been channelized and used as dumping grounds for trash, sewage, stormwater runoff, and industrial waste since the colonial period. In fact, “urban stream syndrome” is a common condition characterized by flooding, high concentrations of nutrients and contaminants, altered channel shape and size, and impaired ecology. Many urban streams are so contaminated or modified that they no longer support life. The challenges of flooding and pollution along Gadsden Creek are serious, but they are common and can be overcome with thoughtful science and responsive design.

Robinson Design Engineers has been leading projects to revitalize urban creeks, daylight buried streams, restore wetlands, improve water quality, and connect communities to water since 2008. We have prepared this report to document the history of Gadsden Creek and the legacy of abuses that the Creek and its surrounding community have suffered in recent memory; to offer an assessment of Gadsden Creek in its current condition—its hydrology, ecology, and its trajectory toward healing; and to stir the imagination of Charlestonians by citing examples from other cities who faced similar challenges but chose to preserve and enhance the aquatic ecosystems of their ancestral landscapes.

Our experience convinces us that Gadsden Creek can, and must, be preserved and revitalized.

Introduction 3 Robinson Design Engineers

A Salt Marsh in the Old City

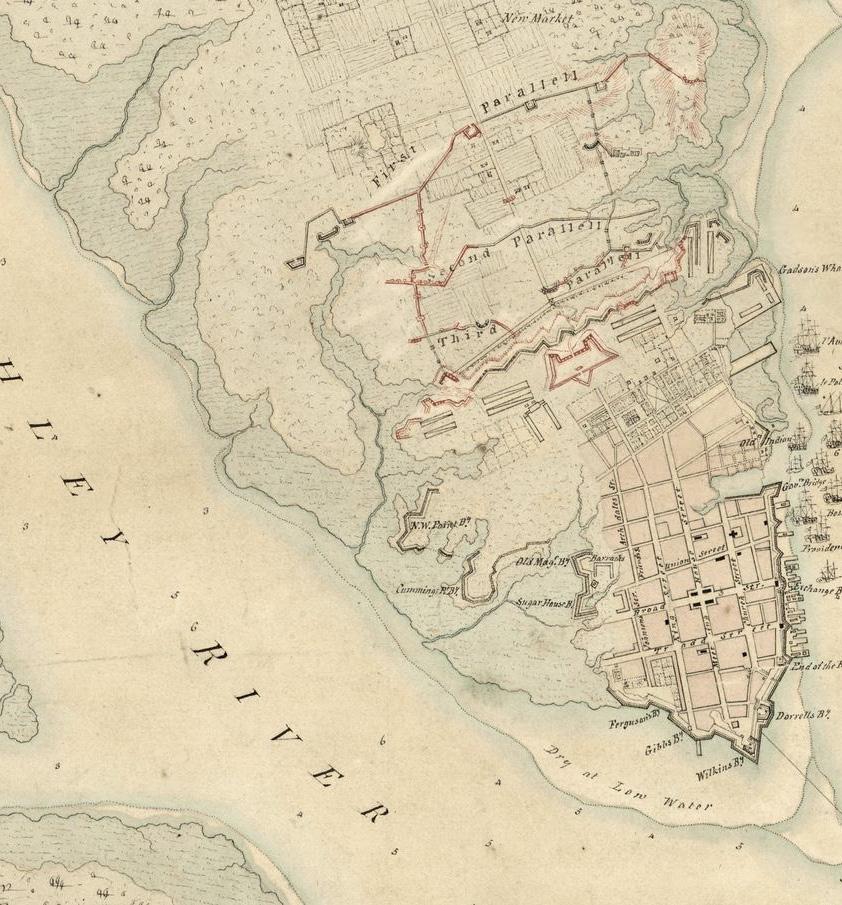

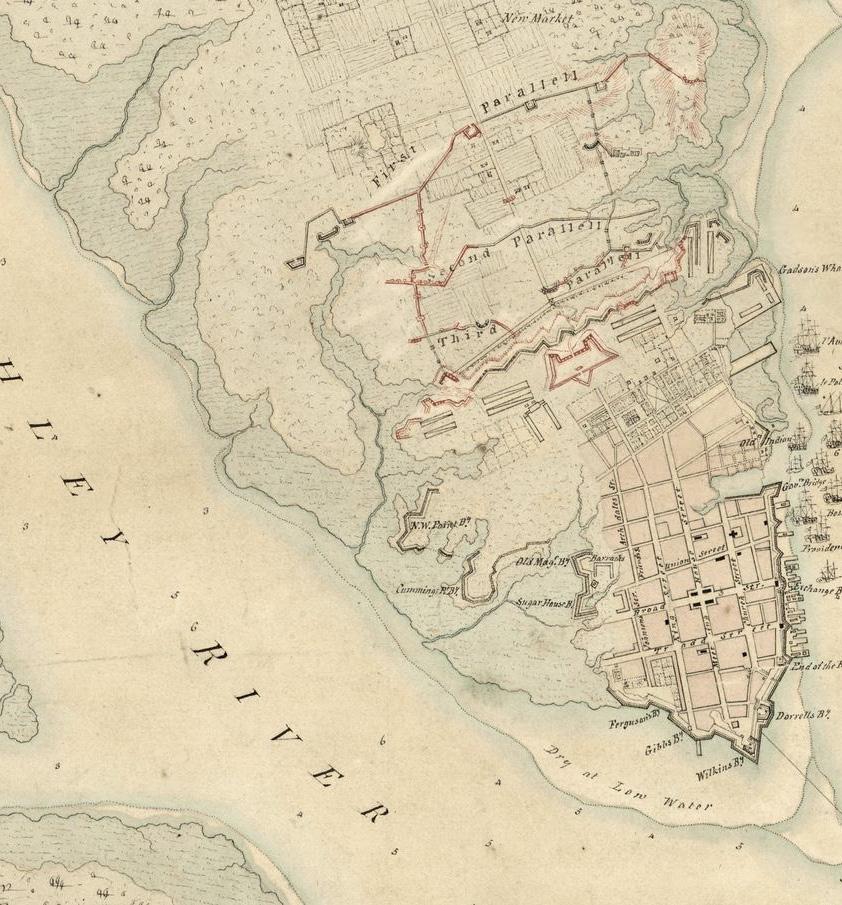

When European colonists settled in Charleston in the late 17th century, the peninsula was significantly smaller than it is today. The natural high ground was a narrow spit bordered by extensive marshes and creeks—particularly along the Ashley River. For centuries before colonization, as the Ashley and Cooper Rivers mixed and met the tides of the Atlantic Ocean, the sediments they carried deposited and formed land.

The South Carolina Coastal Plain is characterized by a series of marine terraces corresponding to several distinct, abandoned shorelines. Charleston is part of the lowest terrace—the Pamlico—and the elevation of this land is within twenty-five feet of the current sea

level. During each phase of oceanic transgressions during the Pleistocene, sediment deposits formed bars and islands. These depositional features created new landforms that altered the flow of water from the landscape and from the sea. The Charleston peninsula and harbor, along with the vast salt marshes and tidal creeks of the Lowcountry, were formed in this way over long periods of time. The process of land formation was punctuated by coastal storms, where violent wave and wind activity delivered large quantities of sediment, shell, and organic matter, and where the physics of erosion and deposition helped to form the ridges of high ground where King and Meeting now lie.

4 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

1872 map titled, Bird’s eye view of the city of Charleston, South Carolina, with Gadsden Creek marked by a red rectangle. (Source: Library of Congress)

At the time of the American Revolution, Charleston was centered on the intersection of Broad and Meeting Street on the eastern side of the peninsula, facing the harbor. The fortification drawn in red is the now Marion Square. To the west and north, marshland and tidal creeks prevailed. In her book Lowcountry at High Tide: A History of Flooding, Drainage, and Reclamation in Charleston, South Carolina, Christina Rae Butler explains that after the Revolution, “The new city government adopted the responsibilities of the colonial commissioners and expanded them further, creating new standing committees to manage specific city improvements and services. […] Motives for filling grew more complex and ambitious as the City Council took an active interest in public health and sanitation. […] City workers used spoils from digging privies, cisterns, or basements to fill low sections of private lots and public streets, and they opted for inorganic rubbish for fill whenever it was available or affordable. When the city could not procure clean inorganic fill, they resorted to offal and residential waste. Refuse, including ash and debris from Charleston’s many fires, animal remains, and industrial waste, were also used as fill material.” (from pages 35-36).

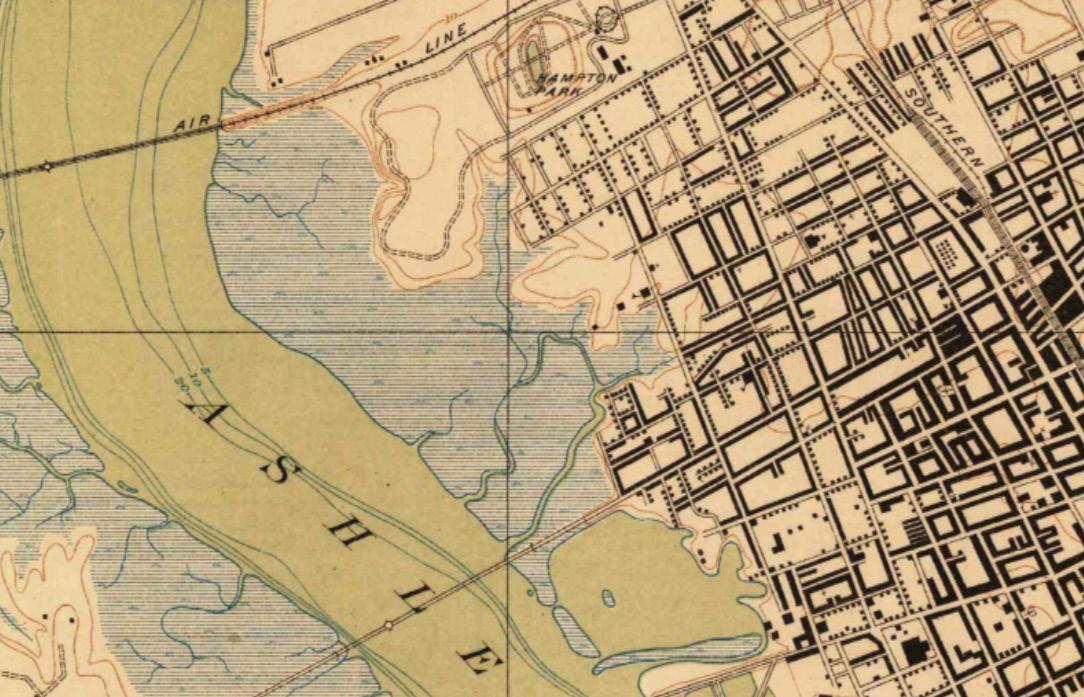

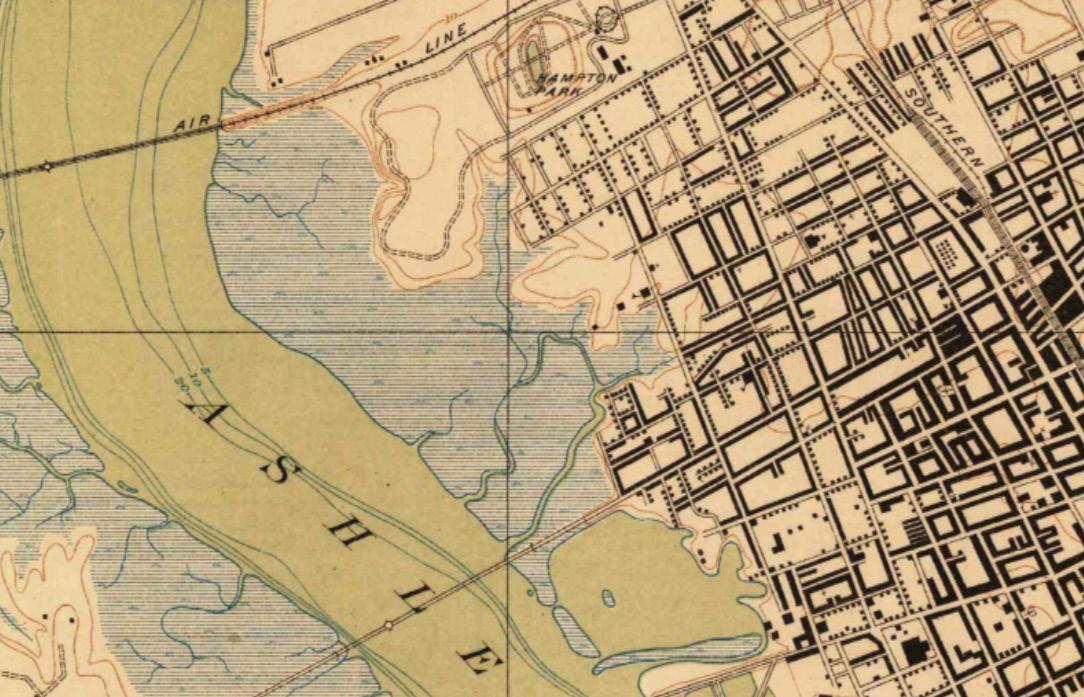

A century later, the City’s landfilling efforts had expanded north and west to the banks of Gadsden Creek. Significant fill was added to the western portion of the city boundaries, facing the Ashley River, as shown in this map from 1872. On the northwestern fringe of the city, the headwaters of Gadsden Creek were likewise built up and built on and bifurcated by President Street. In 1888, the City announced plans for expansion and connectivity between the established inland neighborhoods and the west side, as Butler describes: “Line Street would be carried west of its terminus at President Street to the navigable waters of Gadsden’s Creek, while Congress, Moultrie, and Huger would be extended west towards the Ashley River ‘over a salt marsh foundation, which offers very accessible points for the deposit of city offal’” (pg. 116).

Known as ‘Made Land,’ much of today’s downtown peninsula rests on centuries of municipal waste. Little by little, the marsh at the fringe of the city boundaries, shown in this USGS survey from 1918, were ‘reclaimed’ for land development, often to the detriment of the established residents who lived and worked along Gadsden Creek. Despite the filling along the marsh-land interface, until the mid-twentieth century Gadsden Creek and the surrounding marsh were natural and served as a popular spot for swimming and fishing. The channel was wide enough and deep enough for motorboats, and a few docks reached from Spring Street out into the creek.

Hand-drawn map from 1780 titled, The Investiture of Charleston, S.C. by the English army, in 1780., with Gadsden Creek highlighted by a red rectangle. (Source: Library of Congress)

Hand-drawn map from 1780 titled, The Investiture of Charleston, S.C. by the English army, in 1780., with Gadsden Creek highlighted by a red rectangle. (Source: Library of Congress)

5 Robinson Design Engineers

U.S. Geological Survey map from 1918 titled, South Carolina: Charleston Quadrangle, with Gadsden Creek highlighted by a red rectangle. (Source: USGS)

6 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

View from Hagood Avenue and the beginnings of City of Charlestons’ municipal landfill in 1954. (Photo Credit: Post & Courier)

But during the postwar economic boom in the 1950’s the City of Charleston focused their land-building efforts on Gadsden Creek and initiated an aggressive sanitary City dump, motivated by racism and a desire to create dozens of acres of new land between Gadsden Green and the Ashley River. In 1955, the Charleston Landfill began receiving sanitary waste and dumping it into the Gadsden Creek marsh along present-day Hagood Avenue and Fishburne Street in front of the Gadsden Green community. Trenches approximately 12 feet deep were dug into the soft marsh sediments, filled with garbage, and compacted.

The peaceful marsh views from Gadsden Green were replaced by cranes and the continuous traffic of garbage trucks.

Even after a decade of landfilling, the Gadsden Creek channel remained relatively natural in the mid-1960’s. The Charleston Landfill gradually creeped south from present-day Fishburne Street, and photos from the time show that a motorboat repair facility operated along Spring Street with a dock and pierhead extending into Gadsden Creek. Several years later, the Gadsden Creek channel was ditched and straightened to make way for more garbage, and the salt marsh surrounding the creek was almost completely decimated by the filling.

7 Robinson Design Engineers

By the late 1960’s most of the salt marsh had been filled with compacted garbage, totaling approximately 95 acres of “made land”. In February 1971, the Army Corps of Engineers issued an “after-the-fact” permit to close the landfill. In 1974, the Army Corps authorized a permit to “Relocate Gadsden Creek” at “The City of Charleston landfill site” to make way for a proposed $50 million commercial and residential development called “Ashley Square”. Soon thereafter Gadsden Creek was straightened and channelized, and its banks were rebuilt with soil and shards and concrete and brick. Despite this extensive work, the Ashley Square development never materialized, having been stalled by the weak economy and inflation. However, correspondence associated with the planning phase of the Ashley Square project reveals that Charleston’s engineering staff were already concerned about stormwater flooding in the area. A letter dated February 4, 1974 from the Assistant City Engineer, R.C. Davis, to the Acting City Engineer, J.G. Snowden, contemplated a bridge at Lockwood Drive over Gadsden Creek in lieu of the under-sized culvert, or adding extra culverts and outlets to the Ashley River. The letter even includes hydrology calculations that estimate the stormwater flooding that could occur if nothing were done: A flooding potential of 70,000 gallons per minute to 165,000 gallons per minute. A handwritten note at the bottom of the letter poses the question, “will a lift station be required?”

After the dumping ended and the channel straightening was complete, the 95 acres of “land” atop the former landfill were subdivided and some of the parcels were sold. Several structures were built atop the former landfill: a new city building to house the Charleston Police Station and Department of Highways and Public, two hotels, a parking garage, an office building, and the South Carolina Employment Security Division were all built on the filled marsh. The City of Charleston created Brittlebank Park on the portion of the landfill directly adjacent to the Ashley River. Stoney Field was built on the north side of Fishburne Street. In the early 1990’s the City of Charleston began plans for a new baseball stadium on the northernmost 9 acres of the former landfill. The new stadium, Joseph P. Riley Jr. Park, was completed in the early 2000’s, and a parking lot was built on the former landfill along the south side of Fishburne Street.

8 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

9 Robinson Design Engineers

Aerial view of the Ashley River, historic marsh, Gadsden Creek, and the encroaching, expanding Charleston Landfill from 1964.

(Photo Credit: Post & Courier)

10 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

View of Hagood Avenue during sunny day flooding. (Photo Credit: Jared Bramblett)

In the decades following the landfill, the land surrounding Gadsden Creek began to subside as the garbage decomposed. The roadways within the former landfill— Lockwood Drive, Hagood Avenue, Spring Street, and Fishburne Street—settled and degenerated and were repaved numerous times. Stoney Field sank three feet and became unusable. Exceptionally high tides began to flood the area, especially Hagood Avenue along the Gadsden Green community. In the late 1990’s, twentyfive years after the City Engineer recommended larger culverts beneath Lockwood Drive, the flooding finally initiated action when the City replaced these culverts with a larger pair of box culverts.

The larger culverts were intended to improve stormwater drainage from the large, urban watershed that flows to Gadsden Creek and into the Ashley River beneath Lockwood. Although these new culverts did improve stormwater drainage out of the creek, they worsened tidal flooding. The larger culverts carry larger flows in both directions. During rain events, the larger culverts allowed the runoff to flow out to the Ashley River more quickly. But during exceptionally high tides, the larger culverts also allowed significantly more tidal water to flow into Gadsden Creek. These greater volumes of tidal water flowed through Gadsden Creek and into the sunken land along Hagood and Fishburne. The land sunk lower, and the tides grew higher. The increasing tides of sea level rise in the last few decades have simply worsened these issues.

11 Robinson Design Engineers

Charleston has been diminishing Gadsden Creek for a long time. But astonishingly, Gadsden Creek and its marshes remain “fully functional... providing the suite of functions generally attributed to salt marsh systems” according to the NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service. Gadsden Creek supports a resident population of oysters, blue crabs, fiddler crabs, and periwinkle snails, cordgrass, rush, saltwort, sea oxeye daisy, and many other endemic saltmarsh species. Shrimp, minnows, and fish swim its waters, and the marsh and fringe uplands provide habitat to a host of shorebirds and songbirds.

Gadsden Creek is a living demonstration of the natural resilience of salt marsh. Despite decades the abuse, the creek and marsh continue to improve, to recover, to expand, to hold flood waters, to provide habitat, and to offer natural beauty and hope for those with eyes to see.

12 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

“The National Marine Fisheries Service believes the marsh and creek proposed for fill would be classified as “fully functional” … Being located in an urban environment, water quality is likely less pristine than if the surrounding landscape was natural; however, the vegetation remains dense and there is little to no hydrological impairments.”

NOAA’s NMFS, June 2015

13

Robinson Design Engineers

View of Gadsden Creek. (Photo Credit: Chris Rollins)

14

Revitalization

Gadsden Creek

Project

Photo Credit: Lindsey Shorter

15 Robinson Design Engineers

Photo Credit: Jared Bramblett

16 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

Photo Credit: Blake Suarez

17

Robinson Design Engineers

Photo Credit: Blake Suarez

18 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

Photo Credit: John Sease

19

Robinson Design Engineers

Photo Credit: Blake Suarez

1954 AERIAL WITH 2020 INFRASTRUCTURE

1749-1836

Map of Charleston

20 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

Cover photo: Jared Bramblett

1 2 3

Charleston

Marriott

Brittlebank

The

Publix at 10

VA Medical Center Medical University of SC Hospital Gadsden Green Homes Arthur

Burke

School Johnson

4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

Joe Riley Baseball Stadium

Police Department

Hotel

Park

Bristol Condominiums

WestEdge

Christopher Community Center

High

Hagood Memorial Stadium

Source: City of Charleston Open Data, Charleston GIS Department and historic 1954 aerial from South Carolina Library of Congress

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 10 11 12 9 21 Robinson Design Engineers 8

The Westside and the Ashley River

1749-1836 Map of Charleston

The landfill was closed in the early 1970’s and the creek has been recovering ever since. Gadsden Creek now supports a thriving ecosystem and is one of the few remaining places in historic Charleston where a community of oysters, egrets, crabs, shrimp, marsh wrens, snails, cordgrass, and other salt marsh species can be found. While the infrastructure around Gadsden Creek has deteriorated, the creek itself has exhibited a tremendous capacity for recovery.

22 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

23 Robinson Design Engineers

Present-day Topography

During large tides, the roads and buildings that were constructed on top of the filled-in marsh are flooded with the waters of the Ashley River. These areas flood because they were built on top of a marsh; marshes are meant to flood. The flooding problems associated with Gadsden Creek are humanmade problems.

Source: City of Charleston Open Data, Charleston GIS Department and LiDAR data from Digital Coast Data, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA)

-19 FT 21 FT 0 FT WATER LEVEL ELEVATION 24 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

25 Robinson Design Engineers

Bathtub Model: Average High Tide (5.5’ MLLW)

During an average high tide, Gadsden Creek and its salt marsh fill with tidal waters from the Ashley River. An average high tide does not cause flooding of the neighboring streets

Source: City of Charleston Open Data, Charleston GIS Department and LiDAR data from Digital Coast Data, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA)

-19 FT 21 FT 0 FT WATER LEVEL ELEVATION

26 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

27 Robinson Design Engineers

Bathtub Model: King Tide (7.0’ MLLW)

During exceptionally large tides, tidal water from the Ashley River spills onto Hagood Avenue and its intersection with Fishburne Street. These areas flood because the land has subsided by as much as three feet.

Source: City of Charleston Open Data, Charleston GIS Department and LiDAR data from Digital Coast Data, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA)

-19 FT 21 FT 0 FT WATER LEVEL ELEVATION

28 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

29 Robinson Design Engineers

Bathtub Model: Major Flood Stage (8.0’ MLLW)

During major tidal flooding, water from the Ashley River fills the low-lying portions of the filled salt marsh. These areas flood because the land has subsided by as much as three feet.

Source: City of Charleston Open Data, Charleston GIS Department and LiDAR data from Digital Coast Data, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA)

-19 FT 21 FT 0 FT WATER LEVEL ELEVATION

30 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

31 Robinson Design Engineers

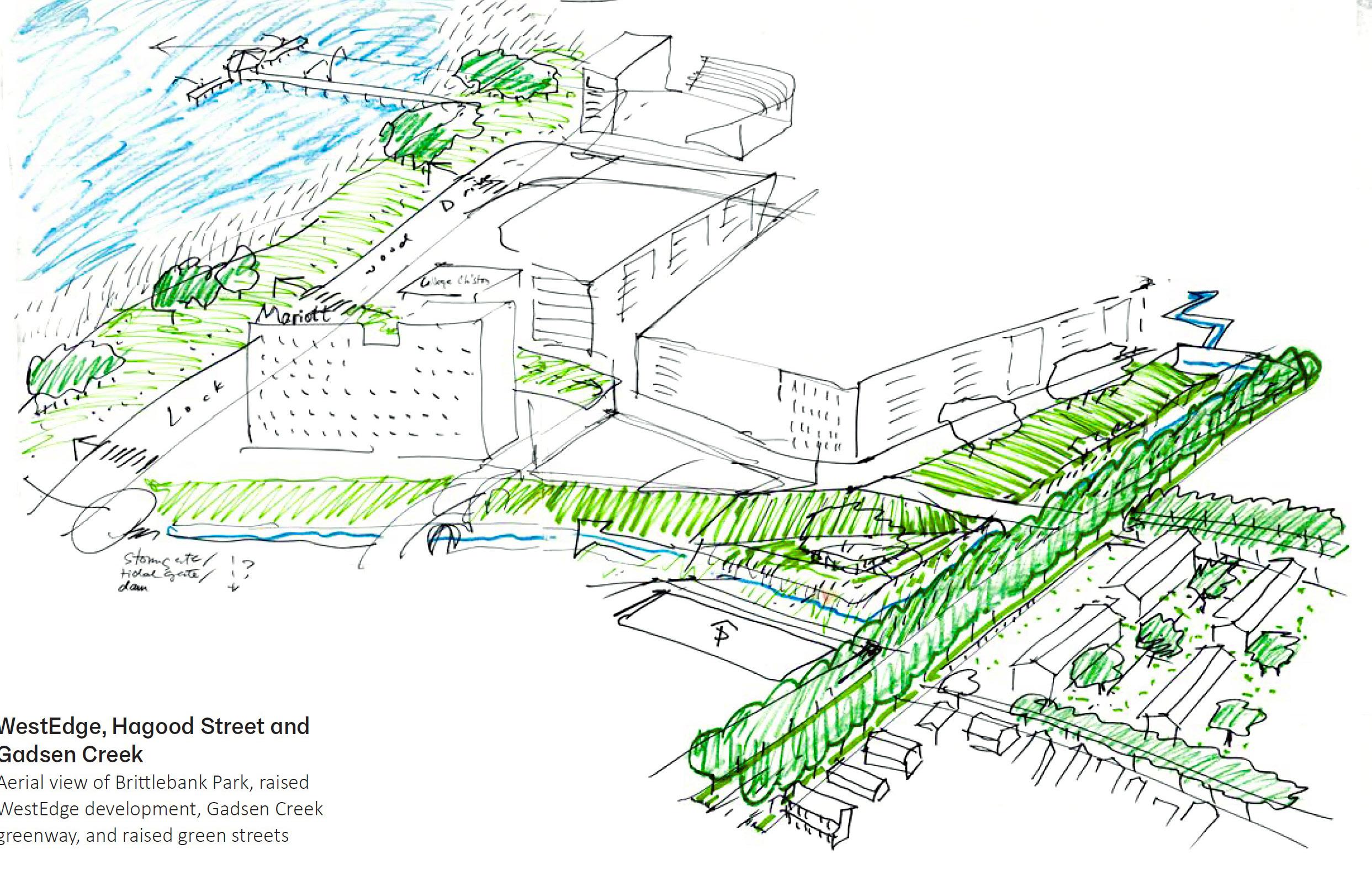

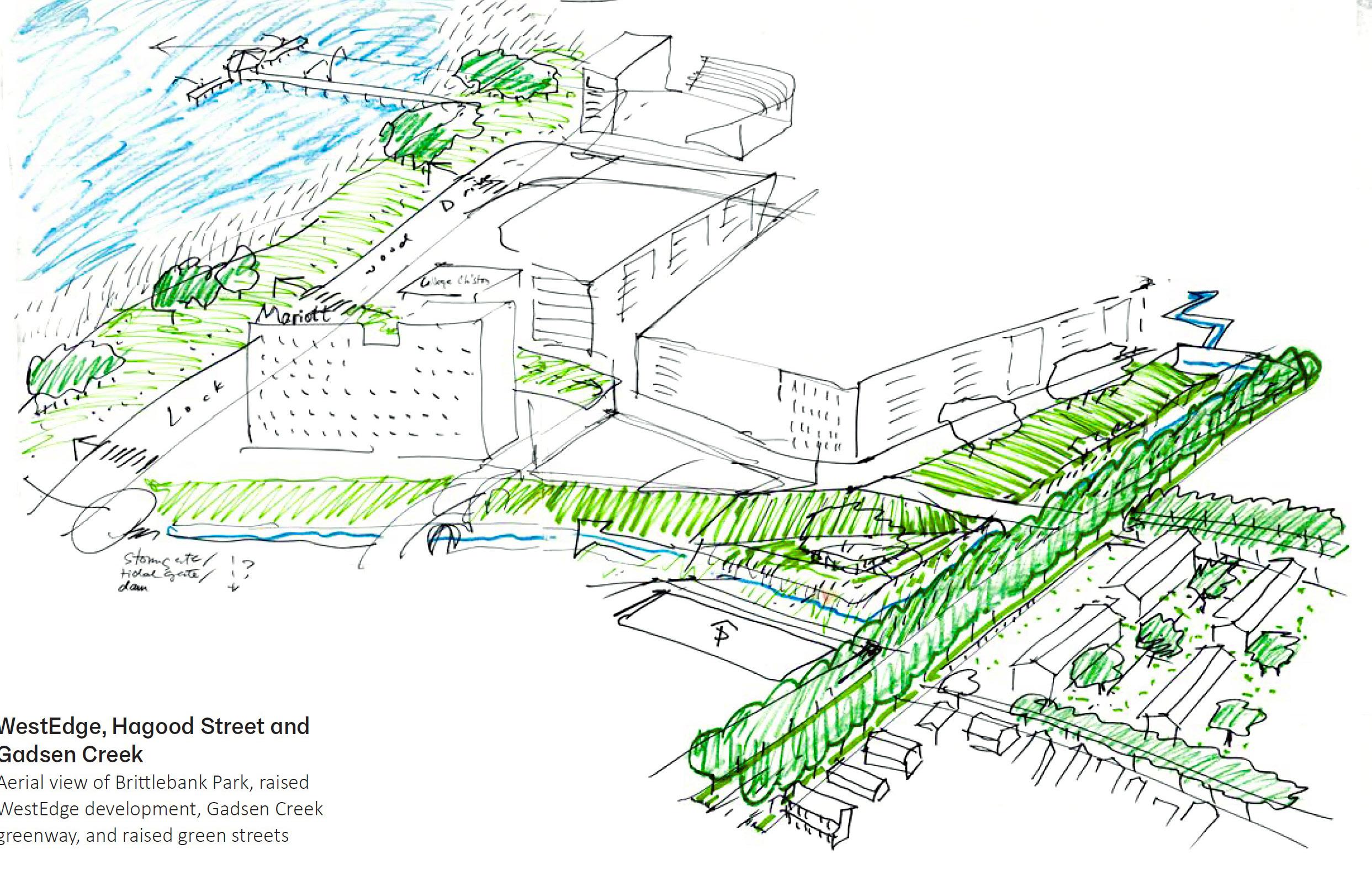

Hand-drawn sketch depicting Gadsden Creek alongside Hagood Avenue with increased green space, tree canopy, and new development. Written notes highlight exploring storm or tidal gates at the mouth of Gadsden Creek.

(Sketch Credit: Dutch Dialogues Charleston Final Report, 2019)

Dutch Dialogues Excerpts

“Connectivity between WestEdge, Gadsden Green and westside neighborhoods should be reinforced. Connectivity enhancements must not impair current drainage; ideally, they would enhance drainage, water storage and infiltration while improving pedestrian, vehicular and neighborhood access.”

“The Dutch Dialogues Team cannot recommend the filling or impairment of Gadsden Creek or its drainage functions. The Creek should be beautified, and its functions enhanced.”

“Covering and filling Gadsden Creek is not recommended given that most of the recurrent and nuisance flooding – whether from tidal influences or stormwater – on the peninsula occurs in areas where natural creeks were filled.”

“We have a bias: to work with the natural and ecological systems that are here. If you ignore them, Mother Nature eventually will win. And make human safety your primary focus. Natural and human -- make those systems work together.”

- Dale Morris, Director of Strategic Partnerships, The Water Institute of the Gulf

“Water is not something to exploit or control; it is something to respect, manage and embrace. Acknowledging and accepting the water system’s primacy, however, yields sober choices but also aspirational options. As Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu observed, “If you don’t change direction you may end up where you are heading.” What follows in this report is, we believe, a pathway towards a safer Charleston.”

32 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

(Sketch Credit: Dutch Dialogues Charleston Final Report, 2019)

“We’re known as a city to be the number one in hospitality in the world. That means, stay a while, come and find a place for you here. We haven’t done that with water. We need to treat water respectfully and be an advocate for water. This is a community effort, and we have to share this cultural mindset.”

Charleston’s future depends upon how well the City and surrounding counties invest to adapt and preserve physical assets, underlying economies of medicine, education, tourism and trade, and enhance residents’ quality of life. Given Charleston’s abundant natural and man-made assets, creatively linking spatial planning, integrated water management, infrastructure and development will yield a compelling vision for Charleston’s future.

Dutch Dialogues Team, 2019

33 Robinson Design Engineers

Covering and filling Gadsden Creek is not recommended given that most of the recurrent and nuisance flooding – whether from tidal influences or stormwater –on the peninsula occurs in areas where natural creeks were filled.”

“

Hand-drawn sketch depicting Gadsden Creek alongside Hagood Avenue with increased green space, tree canopy, and new development. Written notes highlight exploring storm or tidal gates at the mouth of Gadsden Creek.

- Mayor John Tecklenburg, City of Charleston

34 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

35 Robinson Design Engineers Travel Lane Travel Lane Front Yard 12’ Travel Lane 12’ 12’ Travel Lane 12’ 15’ Gadsden Creek 8’ Parallel Parking 6’ Sidewalk Travel Lane Travel Lane Extended Front Yard with Increased Tree Canopy 8’ 5’ 12’ 12’ 17’ Biorentention Planters 6’ Landscape Zone 6’ Pedestrian Zone Gadsden Creek 7’ Pedestrian Zone 4’ Rain Garden Parallel Parking Travel Lane Travel Lane Front Yard Metal Fence Raised Bulkhead Raised Bulkhead 12’ Travel Lane 12’ 12’ Travel Lane 12’ 15’ Gadsden Creek 8’ Parallel Parking 6’ Sidewalk Metal Fence 5’ 7’ King Tide

Conditions Raised Bulkhead Alternative Raised Bulkhead + Green Infrastructure + Road Diet Alternative

Existing

CHALLENGES

ADDRESSES CHALLENGE

PARTIALLY ADDRESSES CHALLENGE

WILL WORSEN CHALLENGE

DOES NOT ADDRESS CHALLENGE

Opportunities

Do Nothing

Storm Surge Barrier

Fill & Pipe Gadsden Creek

Revitalize Gadsden Creek

Stormwater

Tides

Flooding Challenges

StormSurge

LandfillLeachate

Stormwater

AshleyRiverInflow

Water Quality

Tide Regulator

Site Walls

Green Stormwater Infrastructure

Landfill Reclamation

36 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

Challenges Opportunities

Flooding

Stormwater

Dozens of acres of urban land drain into Gadsden Creek. The Spring / Fishburne Drainage Improvement Project will capture much of this area.

Tides

King Tides fill the Gadsden Creek marsh and spill onto the portion of Hagood Avenue that was built upon saltmarsh. The road has sunk several feet in the last few decades.

Storm Surge

Tropical storms sometimes create a surge of water that is much higher than a normal tide. Storm surge events sometimes inundate much of the Charleston peninsula.

Water Quality

Stormwater

Urban stormwater runoff is filled with pollutants from as brake dust, plastics, pesticides, fertilizer, pet waste, and harmful fluids that leak from cars such as oils and antifreeze.

Landfill Leachate

The trash that the City of Charleston dumped into the saltmarsh continues to decompose. Pollutants from the trash leak into the Ashley River and Gadsden Creek.

Ashley River Inflow

The Ashley River itself is polluted by industrial waste, stormwater runoff, and sewer overflows. This water flows into Gadsden Creek and occasionally onto Hagood Avenue.

Do Nothing

Gadsden Creek will continue to improve, and so will its water quality and habitat. Tidal flooding could worsen, but the Spring/Fishburne project will solve stormwater flooding.

Storm Surge Barrier

Perimeter protection will reduce the risk of storm surge flooding. The barrier will require a tide regulator at the mouth of Gadsden Creek, which will reduce tidal flooding.

Fill & Pipe Gadsden Creek

This would worsen all water quality challenges. It would improve tidal flooding, but it would worsen stormwater flooding and extend the duration of storm surge flooding.

Revitalize Gadsden Creek

Replacing the failed culverts, stabilizing eroding creek banks, removing exposed trash, and enhancing the marsh would improve all challenge categories.

Tide Regulator

A modern tide gate would offer the opportunity to restore the hydrology of Gadsden Creek to a more natural condition, thereby improving all challenge categories.

Site Walls

Low barriers like those that the City recently built along East Bay near Sanders-Clyde Elementary School would prevent tidal waters from spilling onto Hagood Avenue.

Green Stormwater Infrastructure

Vegetated roofs, bioswales, and bioretention basins could capture runoff from the urban landscape and improve water quality and stormwater flooding.

Landfill Reclamation

For nearly 40 years, the EPA Municipal Solid Waste Innovative Technology Evaluation Program has offered a path recover and recycle waste materials from the landfill site.

37 Robinson Design Engineers

Thornton Creek

Site Challenges

Water Quality

Project Goals

• Improve water quality of water entering the creek

• Remove sediments and pollutants from the 680-acre drainage area

• Providing public open space and native vegetation

• Facilitate economic development within the Northgate area by integrating the project’s design with adjacent private development

Site History

Historically, the site was hydraulically connected the wetlands surrounding North Seattle Community College with the headwaters of Thornton Creek’s South Fork. In the 1950’s, the area’s affordable land and proximity to I-5 transformed Northgate into a suburban landscape. The Northgate Mall, one of the first retail destinations accessible solely by auto, opened in 1950. Office parks and low-density commercial uses followed.

During this period, the hydraulic connection between the wetlands and the headwaters of Thornton Creek was disrupted when a 60-inch diameter concrete storm pipe was installed and the site was covered with approximately 20 feet of fill and topped with a 5 acre parking lot. Seattle’s 1994 Comprehensive Plan identified as an Urban Center - a target area for new jobs, housing and public investment. Yet, for more than a decade thereafter, political controversy and litigation stymied new development. Much of the controversy surrounded the headwaters of Thornton Creek’s South Fork and its piped flows. Creek advocates fought to exhume the 60-inch storm pipe to create a constructed creek bed, while private land owners focused on developing the Facility’s future site as mixed use commercial property. The controversy created a political logjam between developers, neighborhoods, creek advocates, and Seattle City Hall. In December 2003, a political compromise set the stage for the area’s redevelopment. The City changed outmoded land use regulations, funded a transportation investment plan, and approved communities amenities.

38 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

Urbanizing Watershed

Case Study in Seattle, Washington

Piped Stream

Urban Stormwater Runoff

39 Robinson Design Engineers

Thornton Creek buried below a surface parking lot prior to daylighting in 2006. (Photo Credit: Seven Canyon Trust)

Thornton Creek Water Quality Channel now meanders between residential buildings. (Photo Credit: Seven Canyon Trust)

40 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

Top: View of elevated promenade next to residential buildings and the daylighted creek.

Bottom: Panoramic view of the project site, Thornton Creek formerly buried beneath concrete now daylighted within an urban context. (Image credit: Mithun-Solomon and SVR)

Project Summary

The Thornton Creek Water Quality Channel (the Facility) is a step towards improving the balance between urbanization and environmental sustainability. The Facility is located in the Northgate neighborhood, near the headwaters of Thornton Creek’s South Fork. The Mayor and the City Council established a Northgate Stakeholder Group from 2006 to 2009 whose members represented a broad balance of 22 community, environmental, and business interests. One of the group’s primary missions was to forge consensus on an approach to developing a solution for the South Fork’s headwaters that would meet stormwater treatment, commercial and community goals. The Stakeholder Group evaluated three alternative designs:

1. Daylighting the 60-inch storm pipe to create a creek channel

2. Constructing a natural drainage water treatment system that would treat runoff in a shallow surface channel

3. Creating a hybrid of those two approaches

The City’s collaborative design team worked with the Stakeholder Group and other community members to evaluate the design alternatives against the Project’s goals. In 2009, construction began on the Thornton Creek Water Quality Channel. The facility uses a series of swales and pools to slow and treat stormwater flows from the adjacent 680-acre drainage. Sediments and pollutants are settled out of the stormwater and retained by wetland vegetation, which provides habitat for birds, insects, and other wildlife. The facility will achieve a 40 to 80 percent removal of total suspend solids (sediments and pollutants).

Surrounding commercial and residential development blends into the public open space. Pathways weave through the project. Educational signs, interpretive signs, and “Surge,” a placemaking art piece by local artist Benson Shaw that includes sculptures, bridge accents, lighted glass beads, and blue-lighted walls, creates a unique 2.7-acre green space in the heart of an urban neighborhood. The project is believed to have generated over $200 million in revenue from adjacent private development (retail and commercial).

1. City of Seattle, Thornton Creek Water Quality Channel Final Report (2009)

2. http://www.designforwalkability.com/caseone

41 Robinson Design Engineers

Image showcasing a pedestrian bridge with child roller skating. Water feature is shown as part of the water quality channel with wetland plant species. (Image credit: Mithun-Solomon and SVR)

New Belgium Brewery

Site Challenges

Project Goals

• Improve the stream corridor, through bank stabilization, native plantings, and contouring of the stream bank

• Capture and treat the first inch of stormwater from the neighborhood

• Capture rain for irrigation at the brewery site

Site History

The 18-acre site was formerly an industrial and agricultural hub for more than a century, having been developed for a variety of different uses throughout the years. In the 1800s, it was part of the Buncombe Turnpike, a footpath for agricultural trading between Asheville and Charleston, SC. In the early 1950s, it became home to the Western North Carolina Livestock Market, and the property became an informal community center. Throughout the 1900s, many families operated businesses alongside the Market, including an auction house, a transmission shop and a salvage yard. According to John Bell, one of the owners of Main Auto Parts salvage yard, local children went to college and families were raised on the revenues from this regional economic hub. Throughout with 1980s, a construction and demolition landfill was in service on this site.

When a site assessment was completed by New Belgium Brewery, onsite contaminants including a small amount of lead-based paint, some petroleum, methane (from organic decomposition), asbestos containing materials and lots of construction landfill debris were found to be present. Before redevelopment, the project site was bisected by a neglected creek, essentially a ditch full of old tires and concrete rubble.

42 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

Image of the Main Auto Parts salvage yard. (Photo Credit: Asheville Citizen Times)

Hazardous Leachate Pollution Industrial Site Historic Landfill Case Study in Asheville, North Carolina

Project Summary

After more than a century of industrial use, the cleanup and redevelopment process for this site was bound to be long and complex. In conjunction with the City of Asheville, a local nonprofit RiverLink, New Belgium Brewing Company, and a $400,000 grant from the Clean Water Management Trust Fund (CWMTF) the Craven Street Improvement Project is a public infrastructure project was born. The project includes realignment of Craven Street, improved pedestrian transportation, stormwater management and water quality improvement in the unnamed stream bisecting the New Belgium property.

The Craven Street project aimed to capture and treat the first inch of stormwater from the neighborhood through a variety of stormwater quality mechanisms. This includes bioretention areas, bioswales along the road way, rain gardens in parking lots, and constructed wetlands throughout the site. The project will improve

the stream corridor, through bank stabilization, native plantings, and contouring of the stream bank. Additionally New Belgium is capturing rain water for irrigation purposes. These stormwater improvements will capture and treat rain water before entering the stream, reducing erosion, and volume of stormwater runoff.

With input from the community, the unnamed stream was named Penland Creek in honor of the Penland family, which operated an auction house on the property for many years. While restoring Penland Creek, New Belgium planted native riparian vegetation on the streambanks to prevent erosion. The stream is now not only an attractive part of a functioning riparian habitat, but also a focal point of the brewery.

43 Robinson Design Engineers

Image credit to Storm Cunningham showcasing Penland Creek.

1. “Craven Street Watershed Restoration and Innovative Stormwater.” North Carolina Land & Water Fund, https://nclwf. nc.gov/funded-projects/innovative-stormwater-highlights/ craven-street-watershed-restoration-and-innovative

2. “Craven Street.” Riverlink, https://riverlink.org/projects/cravenstreet/

44 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

The Western North Carolina Livestock Market

(Photo Credit: Asheville Citizen Times)

New Belgium Brewery next to Penland Creek.

(Photo Credit: Mark Herboth Photography LLC)

Less than a decade ago, the water meandered around rusted car bodies, tires, and slabs of concrete that had been tossed there over the years, part of an old, unpermitted landfill that oozed with heavy metals and hydrocarbon pollution.”

“

Landscape Architecture Magazine, 2021

45 Robinson Design Engineers

Fresh Kills Landfill

Site Challenges

Project Goals

• Outline goals, a design vision, and a framework plan for Freshkills Park

• Demonstrate that the vision and goals are responsive to the community and city agency desires, and are grounded and realistic

• Advance discussion at the leadership level regarding design direction, finance, and steward options

• Build broader understanding and leadership for the project

Site History

The City of New York established the Fresh Kills Landfill in 1948, before there was any large–scale development on the west shore of Staten Island. The Fresh Kills site in its natural state was primarily tidal creeks and coastal marsh. By 1955, Fresh Kills was the largest landfill in the world, serving as the principal landfill for household garbage collected in New York City. At its peak of operation in 1986-87, Fresh Kills received as much as 29,000 tons of trash per day and employed 680 people. The four landfills mounds on the site are made up of approximately 150 million tons of solid waste.

While New York City had a number of operating landfills in the latter half of the 20th century throughout the five boroughs, many were closed as new landfill and environmental regulations came into effect. Fresh Kills, however, was allowed to remain open through a Consent Order between the State and the City and the site was retrofitted to meet these regulations. By 1991, Fresh Kills was New York City’s only operating landfill receiving residential garbage.

In 1996, a state law was passed requiring that the landfill cease accepting solid waste by December 31, 2001. By 1997, two of the four mounds were closed and covered with a thick, impermeable cap; and the landfill received its last barge of garbage on March 22, 2001. New York City’s garbage is currently shipped to landfill locations in places such as Pennsylvania and Virginia.

46 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

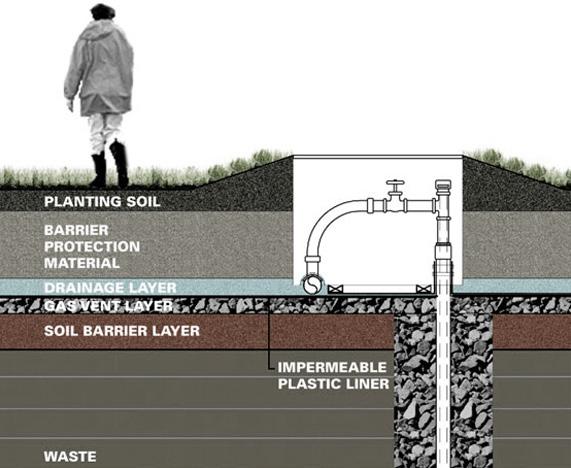

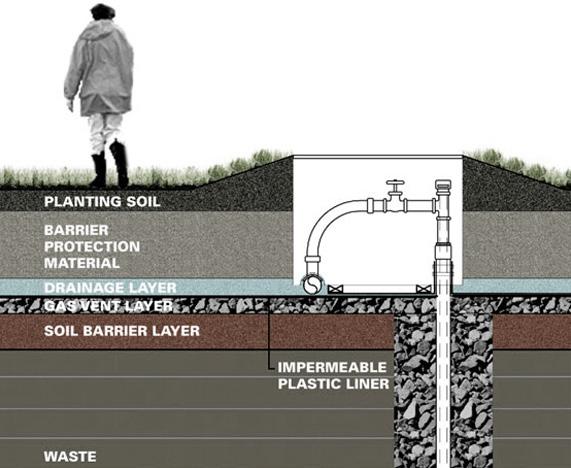

Section diagram depicting landfill capping (Source: New York Department Parks and Recreation)

Leachate Pollution Interfacing Tidal Wetland Historic Landfill

Study in New York City, New York

Hazardous

Case

Project Summary

The New York Department of State, through the Division of Coastal Resources, provided funding for the Fresh Kills Park Master Plan under Title 11 of the Environmental Protection Fund and in 2006 published a draft of the parks master plan. This master plan offers a glimpse into a visionary plan for the former landfill site.

The Draft Master Plan was undertaken with an extraordinary participatory planning process involving affected stakeholders and the general public. Over a course of two years, numerous large public meetings, smaller planning and design workshops, and many additional meetings with elected representatives, stakeholders and public agencies, were held to reach a vision for Fresh Kills Park. There was a broad-based consensus for a park filled with expansive open spaces, recreational uses, innovative programming opportunities and access to the waterfront.

At 2,315 acres, Fresh Kills is nearly three times the size of Central Park. The transformation of Fresh Kills from landfill to park will be one of the most ambitious public works projects of this magnitude, driven by an ecological restoration program that will in turn provide extraordinary settings for enjoying the natural landscape, public art and recreational activities not typically accommodated in big-city environments. The Draft Master Plan provides a blueprint for reclaiming one of the world’s largest landfills for public use, and is a critical step in the longterm development of Fresh Kills Park. The city, and the project team, commits to making Fresh Kills Park a model for end-use development and land reclamation projects.

The Draft Master Plan, published in 2006, describes a vision and framework for review, discussion, and decision-making. Its recommendations are not fixed or

47 Robinson Design Engineers

Early photo of Fresh Kills Landfill during operation. At it’s peak in 1986, the landfill was receiving more than 29,000 tons of trash per day. (Photo Credit: DSNY)

final. The input of many experts, policy makers, and the public was critical for the refinement of the plan over the remainder of the planning process. The project began construction in 2008 and was planned to be phased over time after the release of the final master plan. New public spaces, amenities, and landscape will be built and opened to the public every few years. This project has been a model of continued public engagement. As the scale and unusual nature of the project site, interest and enthusiasm at public meetings have culminated in a list of themes advocated by stakeholders. To list a few:

• Activate the park

• Create opportunities for waterfront recreation

• Create educational opportunities

• Capitalize on Fresh Kills’ vast scale to improve regional natural resources

• Environmental Health and Safety

• Promote youth recreation

• Create opportunities for art and culture

Landfill operations and closure are subject to numerous local, state, and federal regulations that ensure public health and safety. The Fresh Kills Masterplan will be subject to the City Environmental Quality Review (CEQR) and State Environmental Quality Review (SEQRA), and will be examined in an environmental impact statement. Once the site is open for park use, continual monitoring of the water and air will continue for the duration of the required post-closure maintenance period to ensure that allowing public access does not impact public health.

The first phase of construction will begin with North Park. Top image is a rendering for the entry point for North Park. (Source: Fresh Kills Park Website)

Bottom image is a rendering of North Park’s bird tower and creek-front paths.

(Source: Fresh Kills Park Website)

48 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

1. The Freshkills Park Alliance, Fresh Kills Park: Draft Master Plan (2006)

49 Robinson Design Engineers

Smith branch

Case

Site Challenges

Project Goals

• Improve water quality by fostering natural resilience to site conditions

• Restore environmental habitat by providing forage and shelter for pollinators, aquatic invertebrates, and birds

• Facilitate human use by improving the urban landscape

Site History

Since 2014, Robinson Design Engineers has provided geomorphic assessment, hydrology data collection, hydraulic analyses, regulatory coordination, and engineering design for approximately 2,000 linear feet of urban creek channel in Columbia, SC. Half of this reach has been fully contained underground within double 84” concrete culverts since the 1950’s.

These extreme hydraulic forces required a unique design approach for the upstream, open channel reach of Smith Branch. The sandy soils and fully-mobile channel bed precluded the use of popular boulder structures. Instead, a series of carefully designed constructed riffles and expansion pools were used for grade control and to force a hydraulic jump to occur along the channel in prescribed locations. Importantly, these riffles were designed to occur at specific points along the future greenway, so that the sound and interest of the riffles could be enjoyed by greenway users. The downstream reach was “daylighted”—brought to the surface— for the first time in over 65 years. A new, natural “water quality channel” was excavated in the floodplain to convey baseflow and small storm flows.

This channel was appropriately sized for the natural, original hydrologic landscape of the watershed. The unnaturally-large flood flows will then be diverted back into the existing 84” culverts. The natural water

50 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

Study in Columbia, South Carolina

Piped Stream Urban Stormwater Runoff Frequent Flooding Water Quality

Joshua Robinson of Robinson Design Engineers (RDE) pictured in the constructed channel. (Image source: The New York Times)

quality channel is protected against the erosive, highenergy storm flows from the urban landscape. The low gradient, riparian vegetation, and constructed pool features in the new channel also provides stormwater quality improvement.

Project Summary

This project, which involved the physical rehabilitation and ecological restoration of approximately 900 linear feet of Smith Branch, was undertaken by Bull Street Development, LLC and the City of Columbia as part of an urban revitalization project on the former state hospital campus at Bull Street. The upstream end of the project reach is a culvert beneath the rail line near the intersection of Harden Street and Calhoun Street. The downstream end of the project reach is the entrance to the pre-existing, twin 84-inch culverts at the former location of Preston Drive.

Prior to the project, this reach of open channel along Smith Branch suffered many of the common problems of urban streams and was characterized by eroding banks, accumulation of trash and debris, invasive vegetation,

and poor ecological diversity. The restoration of the 2,000 linear feet of open channel has been referred to as “Reach 1” in the overall project. A series of carefully designed constructed riffles and expansion pools were used for grade control and to force a hydraulic jump to occur along the channel in prescribed locations. Importantly, these riffles were designed to occur at specific points along the future greenway, so that the sound and interest of the riffles could be enjoyed by greenway users.

The downstream reach referred to as “Reach 2” was “daylighted” —brought to the surface— for the first time in over 65 years. A new, natural “water quality channel” was excavated in the floodplain to convey baseflow and small storm flows. The low gradient, riparian vegetation, and constructed pool features in the new channel will also provide stormwater quality improvement. Reach 2 did not require Section 404 permitting however, the work along Reach 1 was covered by Nationwide Permit No. 27.

51 Robinson Design Engineers

Hydraulic structure under construction in 2018.

52 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

Bur Marigold growing at the edge of the constructed wetland.

(Image: Robinson Design Engineers)

New growth along the restored floodplain one year following construction.

Water control structure and rehabilitated creek channel immediately following construction.

53

Engineers

Robinson Design

Proctor Creek

Challenges

Project Goals

• Water quality improvements for the creek

• Create greenspace and increase the use of green infrastructure

• Research how downtown development contributes to increased stormwater and decreased public health

• Plan and implement projects to offset threats using the Proctor Creek Community approved PNA Study (Proctor Creek North Avenue)

• Engage communities to become stewards of Proctor Creek

• Foster economic development for community

Site History

In the late 1800s, Atlanta began burying creeks (including Proctor Creek) in ‘combined sewer’ pipes that carry both sewage and stormwater and flow into creeks and rivers downstream. During the mid to late 1900s, the sewers would frequently overflow during rainstorms and release untreated sewage into the creeks

By 1995, a lawsuit was filed by the Chattahoochee Riverkeeper and a coalition of partners. The lawsuit was settled in 1998 and prompted the City of Atlanta to begin major sewer upgrades. The city separated the Greensferry combined sewer area into separate sewer and stormwater systems. The North Avenue area remains combined. While the amount of untreated sewage flowing into Atlanta’s creeks and rivers have been significantly reduced, Proctor Creek today is still considered impaired. In addition, the watershed is troubled by frequent flooding, erosion, stormwater runoff, and pollution from illegal dumping

The many neighborhoods that make up the Proctor Creek watershed also hold important historical and cultural significance for Atlanta. The watershed’s long list of landmarks includes: the first park in Atlanta to be opened to African Americans (Washington Park), the first and only African American public high school in the city until 1947 (Booker T. Washington High School), and the largest grouping of Historically Black Colleges and Universities in the country (the Atlanta University Center).

The area was once a major focal point of the Civil Rights Movement and prominent leaders who have called the watershed home include W.E.B. Dubois, Maynard Jackson Jr., Julian Bond, Coretta Scott King and Martin Luther King Jr. The Proctor Creek watershed today is home to more than 38 neighborhoods, including some of the most economically-disadvantaged and underserved areas in Atlanta.

Residents and stakeholders are taking action to turn around decades of neglect and disinvestment and to help restore the watershed and protect its residents

54 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

Study in

Site

Pollution Case

Atlanta, Georgia

Urban Stormwater Runoff

Frequent Flooding

Project Summary

The northwest Atlanta project, better known as the Proctor Creek Watershed Project began in 2010 as a result of flood-related, housing and environmental challenges identified by community leaders, federal agencies and the City of Atlanta. EPA’s Office of Environmental Justice and Sustainability, Brownfields program and Water Protection Division were the first to engage with the City and neighborhood representatives during that year. Currently, Proctor Creek has poor water quality and a severely altered hydrology due to illicit sewer connections, combined sewer overflows, sanitary sewer overflows, and high volumes of contaminated storm water runoff during rain events. The biggest challenges that these communities face and have expressed to the EPA are stormwater flooding, flooded housing, mold and mildew in the homes, illegal tire/trash dumping, abandoned and derelict properties, high crime and lack of policing and lack of economic opportunity. The community’s goal is to have a clean,

safe and sustainable creek-side community where they can raise their families.

The Partnership for Sustainable Communities (PSC) is working toward a full scale restoration of the Proctor Creek Watershed with environmental, infrastructure and economic components. The PSC is supporting local leaders in the development of strategic relationships, recognizing and expanding assets that add value, and investing in innovation. A framework is being developed with the EPA, HUD, DOT, USACE assistance to integrate multiple ecological, economic, and infrastructure frameworks. Community health benefits of the project area are being evaluated through a health impact assessment (HIA). Atlanta’s global vision is being leveraged to align the residents, public health, and business communities to create a more sustainable environment promoting community revitalization, environmental improvement, and infrastructure upgrades.

55 Robinson Design Engineers

Image by Stephen Noland depicting water and debris in Proctor Creek.

Communities in and around the Proctor Creek Watershed have long suffered from pollution caused by Atlanta’s aging sewer infrastructure, disinvestment in the urban core, illegal dumping and other environmental and public health hazards.

The strength of the Partnership will be realized through collaboration with residents who have assets, local knowledge, and a history of action focused on restoring the watershed.”

West Atlanta Watershed Alliance, 2015

1. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Proctor Creek Watershed Story Map (2020)

2. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Proctor Creek Fact Sheet (2014)

56 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

“

Proctor Creek in a debilitated state with litter and waste pilled in and around creek bed. Illegal dumping has resulted in piles of trash in and around Proctor Creek.

In recent years, citizen science in air and water quality monitoring and other community-based approaches have been used to address a wide range of health and environmental justice challenges in community settings.

57 Robinson Design Engineers

(Source: West Atlanta Watershed Alliance)

(Source: West Atlanta Watershed Alliance)

Site History

Winding through the grid of streets, Waller Creek is a prominent feature that helped shape the historical evolution of the city. Once close to the eastern edge of town, it now lies within the heart of the city. But, despite its central location, the creek does not play a central role in the life of the community. Rather it is concealed within the Downtown, following a deep and narrow corridor that appears even deeper and is made narrower where it has been channelized. Periodic flooding has limited investment along the creek corridor, giving the area an underutilized and abandoned character. At the same time, projects that have been built in the last couple of decades turned away from the creek, locating parking and service functions along it.

Waller Creek

Site Challenges

Urban Stormwater Runoff

Project Goals

• Build an ecologically robust and resilient urban creek, riparian corridor, and park system

• Steward the ecological system built along lower Waller Creek long term

• Cultivate the next generation of environmental stewards

• Become a national leader in the fields of environmental stewardship and urban greenway projects

Although attempts were made in the past to build pathways along the creek, they were not always successful. In the most constrained reaches of the corridor, they resulted in the addition of concrete stairs, pathways and ramps that take away the opportunity for landscape or that encroach into the natural creek banks and bottom. Some pathways became an attractive nuisance, leading people down to places that are unattractive, unsafe and unsanitary. The creek corridor became a refuge for homeless people who find shelter under the bridges and along the paths. Despite city maintenance and periodic clean up events, the creek is littered with trash and debris. Aging infrastructure exacerbates the problems of pollution, and water quality is affected by storm sewer discharges and the potential for leaking wastewater lines

58 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

Case Study in Austin, Texas

Frequent Flooding Water Quality

Construction of channel with features including limestone walls and a vegetated slope. (Waller Creek Masterplan)

Waller Creek faces considerable challenges today. It has serious problems related to environmental health, safety and sustainability, image, appearance and identity, and connectivity within the corridor and to other parts of the city. Although many years have passed since Lyndon Johnson decried its condition in the 1930s, Waller Creek still remains essentially a negative element in the city, plagued by flooding, homeless encampments, pollution and neglect. The decision by the people of Austin in 1998 to invest in significant flood control improvements along Waller Creek will be looked upon as a landmark event in the history of the city, comparable to the damming of the Colorado River in 1893. With this investment, there is an exciting opportunity to reconnect and reorient the city to the creek and make it the centerpiece of a revitalized east side of Downtown. When completed in 2014, the mile-long Tunnel will remove 28 acres of Downtown real estate from the 100-year flood plain. But, it is important to recognize that the flood control project in itself will not change Waller Creek’s negative image and identity. In order to foster redevelopment and reinvestment in this area, Waller Creek needs to be improved as a high quality amenity.

Project Summary

Waller Creek, located in downtown Austin, runs 1.5 miles from Waterloo Park just south of the University of Texas to Lady Bird Lake. For decades this creek has been prone to massive flooding and because of this, development adjacent to this creek has suffered and the area became an eye sore. The creek is now surrounded by prime real estate and a massive collaboration between the City of Austin, the Waller Creek Conservancy and architects will not only solve the flooding problem but will create beautiful parks and greenspace’s along with new developments that will turn a neglected area to a beautiful destination for all ages.

Waller Creek now represents the single largest urban creek redevelopment project in the nation. In 2011, work began on a huge $146 million tunnel channeled directly beneath the creek and now runs the entire length of the creek. This will eliminate any potential flooding and opens the door for new development creating what many are calling…. Austin’s new “Central Park.”

59 Robinson Design Engineers

Section graphic depicting a healthy riparian zone with flood benches and aquatic habitat. Graphic illustration is credited to the Waterloo Greenway.

As Austin continues to grow there is going to be the need to build in pieces of public infrastructure, and when I use that term I really mean public space—places that can be used by all constituents,” Peter Mullan [Waller Creek Conservancy’s new CEO] said. “I think Waller Creek will be the most significant of those.”

60 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

“

61 Robinson Design Engineers

1. City of Austin, Waller Creek District Master Plan (2010)

2. Waterloo Greenway Conservancy

Renderings are credited to the Waterloo Greenway Conservancy.

Gowanus Canal

Site Challenges

Project Goals

• Clean up highly contaminated sediment

• Cap the bottom of the Canal with a multi-layer cap

• Identify and address off-site contaminat sources

Site History

The Gowanus Canal was built in the mid-1800s and was used as a major industrial transportation route. Manufactured gas plants (MGP), paper mills, tanneries and chemical plants operated along the Canal and discharged wastes into it. In addition, contamination flows into the Canal from overflows from sewer systems that carry sanitary waste from homes and rainwater from storm drains and industrial pollutants. As a result, the Gowanus Canal has become one of the nation’s most seriously contaminated water bodies. More than a dozen contaminants, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, polychlorinated biphenyls and heavy metals, including mercury, lead and copper, are found at high levels in the sediment in the Canal.

The major potentially responsible parties (PRPs) are National Grid (former MGPs) and New York City (NYC) (combined sewer overflows).

62 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

The Gowanus Canal is a 100-foot wide, 1.8-mile long canal in the New York City (NYC) borough of Brooklyn, Kings County, New York. The Canal is bounded by several communities, including Park Slope, Cobble Hill, Carroll Gardens and Red Hook. The Canal empties into New York Harbor. The adjacent waterfront is primarily commercial and industrial, currently consisting of concrete plants, warehouses and parking lots.

Hazardous Leachate Pollution

Industrial Site Urban Stormwater Runoff

Case Study in Brooklyn, New York

Industry and commercial properties line the Gowanus Canal. (Photo Credit: DLANDstudio)

Project Summary

The Gowanus Canal has been heavily contaminated throughout its existence. In April 2009, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed putting the Gowanus Canal on the National Priorities List (NPL). After consulting extensively with the many stakeholders who expressed interest in the future of the Gowanus Canal and the surrounding area, EPA determined that Superfund designation was the best path to the cleanup of this heavily-contaminated and long-neglected urban waterway. EPA placed the site on the NPL on March 4, 2010.

EPA, in conjunction with NYC and National Grid, performed analysis to characterize the nature and extent of contamination in the canal; determine the human health and ecological risks from exposure to contamination in the Canal; identify the sources of contamination to the

Canal, including ongoing sources of contamination that need to be addressed so that a sustainable remedy can be developed and implemented; and determine the physical and chemical characteristics of the canal that will influence the development, evaluation and selection of cleanup alternatives.

A remedial investigation report and a feasibility study were developed and evaluated remedial alternatives for mitigating human and ecological risks in the canal. The plan consisted of dividing the canal into three sections and dredging the highly contaminated sediment, replacing it with multiple layers of clean material as a multi-layer cap. The remedy also relies on the control of upland sources of contamination to the Canal, including the remediation of three former MGP sites adjacent to the Canal.

63 Robinson Design Engineers

Gowanus canal and the outflow culverts. (Photo Credit: DLANDstudio)

64 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

Working closely with local community organizations, government agencies and elected officials, DLANDstudio initiated and designed a new kind of public open space: a completely modular street-end Sponge Park™. The design equally values the aesthetic, programmatic, and productive importance of treating contaminated water flowing into the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn, an EPA Superfund site. Sponge Parks are a critical component of the Gowanus Canal Masterplan spearheaded by DLANDstudio and Sasaki.

The design of the pilot project is purposefully modular for easy replication. The plants used have been chosen due to their ability to extract heavy metals and biological toxins out of the contaminated water.

(Source: DLANDstudio)

1. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Record of Decision Report for Gowanus Canal Superfund Site (2013)

2. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, March Community Update (2022)

3. “Gowanus Canal Sponge Park™ Pilot” DLANDstudio, https://dlandstudio.com/Gowanus-Canal-SpongePark-Pilot(2016)

65 Robinson Design Engineers

Site History

The Collier County Landfill is located at 3750 White Lake Boulevard, Naples, Collier County, Florida, and approximately 300 acres in size. The landfill includes active and inactive areas (i.e., “cells”) used for the disposal of the garbage and rubbish generated in Collier County. Cells 1 and 2 were unlined disposal areas, comprising approximately 32 acres, located near the northeast corner of the Landfill. These two cells were filled with solid waste from 1976 through 1979, and subsequently closed by the County and covered with a soil cap.

Collier County Landfill

Site Challenges

Hazardous Leachate Pollution

Project Goals

• Decrease site closure costs

• Reduce the risk of ground-water contamination from an unlined landfill

• Recover and burn combustible waste in a proposed waste-to-energy facility

• Recover soil for use as landfill cover

• Recover recyclable materials

As part of the long term solid waste management strategy, Collier County started exploring various alternatives for re-using Cells 1 and 2. Realizing the potential uses of the 32 acres, a landfill reclamation study for Cells 1 and 2 was initiated in 1986. This project has been widely acclaimed as the first planned landfill reclamation project in the United States. In 1991, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency selected the reclamation of Cells 1 and 2 as a demonstration project for the Municipal Solid Waste Innovative Technology Evaluation (MITE) program. This study proved successful for recovering landfill cover material (i.e., soil). Approximately ten (10) acres of the southwest corner of Cells 1 and 2 were mined recovering 50,000 tons of soil suitable for landfill cover and growing plants. The County also recovered significant amounts of ferrous metal and aluminum.

66 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

Fresh Kills Landfill during operation with seagulls flying over mounds of garbage. (Photo Credit: DSNY)

Interfacing Tidal Wetland Historic Landfill

Case Study in Naples, Florida

Project Summary

Florida’s Collier County, like most other local governments, has traditionally allocated solid waste to landfills. However, the heavily regulated landfill process has been expensive and has always posed substantial environmental threat.

The Landfill Reclamation Project, pioneered by County officials, sought to recover and reuse waste materials and gain benefit from the landfill site itself. It employs novel techniques including degradation of organic elements of trash and then reclamation of cover materials and ferrous metals. A technically sound program that greatly reduces environmental risk, it has resulted in lower costs, greater environmental protection, and a better method of solid waste management.

The program consists of a loading machine to perform

the landfill mining and mechanized equipment (normally used in quarry operations) to size-up and separate the materials. The current area being mined is an active landfill site that has stabilized, i.e. the waste materials have decomposed to start producing methane. The excavated material is fed to a filter screen to remove large items. The remainder then passes over a vibrating screen that extracts the finer items. Light ferrous components are then separated through the use of a drum magnet on a conveyor belt. These parts are then stockpiled to be sold to scrap processors for recycling, a process that generates supplemental revenue for the county

Compared to the standard means of handling solid waste, the Landfill Reclamation Project does not involve burning (which can be costly) or manual handling of trash (which can be tedious and unhygienic for

67 Robinson Design Engineers

Bald eagle over Collier County Landfill. (Photo Credit: Fort Myers Florida Weekly)

68 Gadsden Creek Revitalization Project

A wide view of the Collier County Landfill. (Source: Fort Myers Florida Weekly)

handlers). It reverses the landfill concept by introducing an innovative approach to waste treatment through a technology-driven, low-cost process. In doing so, it achieves a high degree of environmental protection through the reclamation of landfilled waste and open space.

Collier County operates its current landfill reclamation project in an area that serves 120,000 (88 percent of its) total residents. The actual reclamation operation produced approximately 50,000 tons of usable material at less than half the cost of new material purchased off-site. The County saved $100,000 in the first year of operation (FY 1988-89). Clearly, the project demonstrates that older, environmentally hazardous landfill cells can be put to good economic use.

In terms of replication, this project is easily adaptable to any community looking to find a viable solution to its solid waste management problems. Already, the Florida department of Environmental Regulation has issued a permit to the National Energy Corporation to mine a 48-acre waste deposit. New York State; the City of Thompson, Connecticut; the City of Alexandria, Louisiana; and the Delaware Solid Waste Authority are either conducting evaluative studies or starting landfill reclamation projects in their respective jurisdictions. In the field of waste management, the Landfill Reclamation Project can be characterized as an imaginative and resourceful approach to tackling the troublesome problem of landfill contamination.

69 Robinson Design Engineers

1. The Innovations in American Government Awards Program, Award: Landfill Reclamation Project (1990)

2. Collier County Solid Waste Management Department, Landfill Reclamation of Cells 1 and 2 (2010)

© Robinson Design Engineers 10 Daniel Street Charleston, SC 29407

robinsondesignengineers.com 2023

Photo Credit: Lindsey Shorter

Gadsden Creek

Photo Credit: Lindsey Shorter

Gadsden Creek

Hand-drawn map from 1780 titled, The Investiture of Charleston, S.C. by the English army, in 1780., with Gadsden Creek highlighted by a red rectangle. (Source: Library of Congress)

Hand-drawn map from 1780 titled, The Investiture of Charleston, S.C. by the English army, in 1780., with Gadsden Creek highlighted by a red rectangle. (Source: Library of Congress)