16 minute read

IN SEARCH OF ROCHESTER’S

IN SEARCH OF ROCHESTER’S RACIAL ROOTS

A WALK THROUGH A COMPLEX HISTORY

Advertisement

BY NICOLE NFONOYIM-HARA

IN 2016, THE SUMMER PHILANDO CASTILE WAS KILLED IN FALCON HEIGHTS, MINNESOTA, I HAD BEEN IN ROCHESTER BARELY

A YEAR. I often think back to that summer as we live through this unsettling pandemic and the labor pains of reckoning and nascent revolution. Racism has deep and intractable roots coursing through the American story. It is all too familiar, even as some deny it. History is full of the silence of this denial. And it is the silences I am often listening for. Today, cities across the country and the world are reflecting on their own racial pasts with fiery debates about monuments and public spaces. And so I went in search of Rochester’s racial roots, wondering what we might pull up when we dig our hands deep into the city beneath our feet.

Rochester’s history is intertwined with that of the Mayo Clinic. Rochester is a community with a powerful master narrative—a story of origins and identity so rooted in the development of its world-class hospital that it can unwittingly obscure the vibrant patchwork of other stories carried by all who call this place home. So I scoured archives from old city papers and publications looking for clues that might point to the early existence of people of color in the area. What follows just skims the surface.

For generations, the city’s population was over 90% white. Today, that figure is edging closer to 78%. There remains, however, a myth that there has never been racial and ethnic diversity in Rochester, and it is not easy to put together a clear and comprehensive history of race in the city. But confronting the myth of racial homogeneity is valuable. Rethinking our

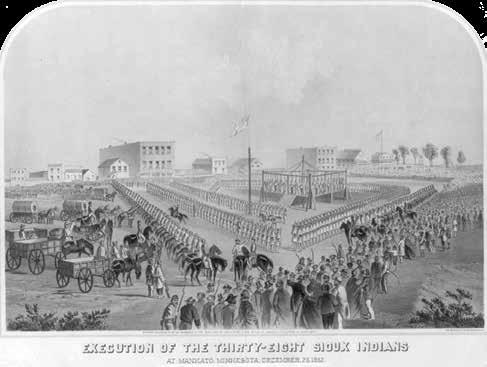

In 1862, thirty-eight Dakota prisoners were executed in Mankato.

collective histories helps to combat ideas of diversity as a new phenomenon and a uniquely modern “challenge.” Diversity is a core part of our past and our future.

NATIVE NARRATIVES

The myth writes people of color out of the narrative. Perhaps the starkest silence is about Native people in Rochester. This area was a crossroads for many Native tribes in the region throughout history. For hundreds of years, it was home to the Dakota (Sioux Wahpeton). Reclamation of the history and recognition of Dakota presence in the area can be seen by the work done in Indian Heights Park.

The Mayo Clinic has its own complex history with local Native communities. In December 1862, a month before President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, he ordered what remains the largest mass execution in our nation’s history to date. Thirty-eight Dakota men, captured prisoners in the Dakota War of 1862, were killed in Mankato. Among the executed was Mahpiya Akan Naži (Stands on Clouds). Dr. William Worrall Mayo received the body of Mahpiya Akan Naži as part of a practice of offering cadavers to local physicians. Dr. Mayo dissected the body and later had the skeleton prepared for display. As part of the Native Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, Mayo Clinic returned these remains to the Dakota tribe for reburial in 2015.

BLACK LIVES IN PRINT

One of the first stories I came across about a Black person in the city looked as if it

The Avalon Hotel was a safe haven for Black travelers to Rochester. Notable guests included Duke Ellington and Count Basie.

had been ripped from the headlines of a more recent paper: “Negro Shot by Police: Rochester Man in Lively Battle with Police.” The article, from 1906, went on to describe “a negro on a rampage” who was shot and “subdued” by two police officers after he pulled out a gun. I was struck most by the description of the man as a “Rochester man.” This man, Charles Johnson, called Rochester home. He was not a drifter or a person passing through. Did he have a family? What had brought him to Rochester? What was his life like before he was immortalized in a few lines of newsprint? A Rochester Post and Record article recounting the shooting offered up some answers citing that he was once employed by the city engineer and had made a living selling junk and doing odd jobs in the community.

Next came the story of a white teen, Henry Stevens, who shot and killed a young Black barber, James Willis, after a dispute in 1871. Willis was an apprentice to H.W. Gray, who was described as a local “mulatto barber.” The story was deemed notable enough that it was retold in the 1910 publication the “History of Olmsted County, Minnesota: Together with Sketches of Many of Its Pioneers, Citizens, Families, and Institutions.” Today, local Black barbers serve a diverse clientele. Who were these early barbers’ clients? Once again, the questions swirled.

Finally, I was haunted by the story of Taylor Combs, a Black patient and inmate at Rochester State Hospital and Asylum serving a 30-year sentence. In April 1889, two white hospital attendants beat him to death. Combs’ breastbone and ribs were broken in the altercation, and the “History of Olmsted County” notes that the injuries were likely due to one of the attendants falling or jumping on Combs. The attendants covered up the homicide as an accident, and the coroner pursued no further action. However, two months later, the coroner had Combs’ body exhumed and found that the injuries were far more extensive. A trial ensued which attracted great media attention from Twin Cities’ papers. The attendants were sent to prison for four years.

REDLINING AND RACISM

These three stories involve violence, crime and murder, but I wonder about the less salacious stories that never made it to print. Archives about Olmsted County and the city dating as far back as the 1870s make passing mention of “Indians,” “negroes” and “mulattoes”—dated language we no longer use, but which signal real people that made up a part of the city’s populace at the time.

A 1946 edition of “The Negro and His Home in Minnesota” refers to six Black families living in Rochester and to the many “distinguished” African Americans who traveled to Rochester to be seen at the Mayo Clinic, where they faced discrimination in the city’s hotels. These practices prompted Verne Manning to found the downtown Avalon Hotel in 1944. Manning bought the building, previously owned by a Jewish family who had served Jewish clientele facing discrimination, after local hotels denied him lodging while his wife was at the Clinic. The hotel became a safe haven for Black travelers to Rochester. Notable guests included Duke Ellington and Count Basie. It was listed in the iconic “Green Book” guide for Black travelers in 1948. From the 1940s to 1960s, the “Green Book” also listed De Luxe Cabins, Samaritan, Gatewood and the YWCA in Rochester as safe and hospitable for Black travelers.

Interestingly, the majority of these sites deemed safe were located in areas redlined in 1940 and considered “declining” or “hazardous.” The areas were mostly in southeastern and central Rochester,

where lower property value assessments fostered inequalities in loan granting, home ownership and wealth accumulation. Today, 76% of Black households rent, and the city’s population of color is most concentrated in areas where renting is prevalent. Redlining maps and discriminatory practices in hospitality and housing point to a local culture that facilitated segregation and systemic inequality. And these problems persist today.

Rochester was also no stranger to outright racist events in the first half of the 20th century. Rochester was considered a central hub for SE Minnesota Ku Klux Klan members. On July 4, 1926, the KKK held a parade in downtown Rochester. In August of 1963, a burning cross was found in front of the Avalon Hotel, the same day an interracial group of community members marched through downtown in support of the Civil Rights movement.

In 1962, the KKK held a parade in downtown Rochester.

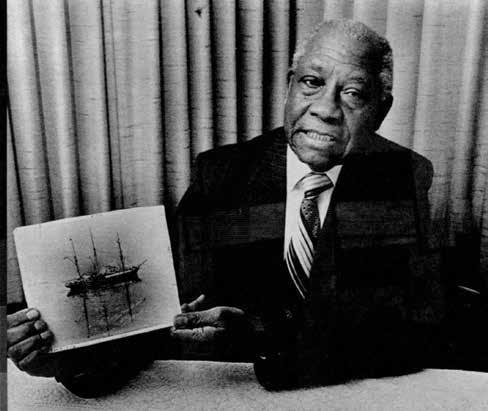

George Gibbs, left, helped to found the NAACP in Rochester. Newspaper clippings from 1963 (left) and 1868 (right) help tell the story of race relations in Rochester.

THE CONTRIBUTIONS THAT MAKE UP A COMMUNITY

Rochester's Committee for Equal Opportunity reported that as of the 1960 census there were “49 Black residents, 26 Japanese, 50 Chinese and 77 Filipinos, out of a total population of 40,663.” IBM attracted a handful of African-American professionals and families beginning in the early 1960s. Among these families were George and Joyce Gibbs. George Gibbs was a community leader and civil rights activist, and in 1965, he helped found the Rochester chapter of the NAACP. A year later, Virginia Mendenhall became the city’s first Black teacher, while her husband, Rodney, served as the first Black instructor at Rochester Community College. In 1979, Mayo Clinic hired its first Black physician, Dr. Franklyn Prendergast. Also in 1979, Charles “Chuck” Hazama, a Native Hawaiian, became mayor of Rochester. The presence of migrant Mexican laborers in Olmsted County and greater Southeast Minnesota also weaves itself into the timeline beginning in the 1960s.

From the 1970s through the 1990s, Rochester’s racial and ethnic diversity continued to grow as immigration increased and Minnesota became a refugee resettlement site. The first wave of Hmong came to Rochester between 1975 and 1985. Somalis began settling in the city as early as the late 1980s, while Africans from Sudan and Ethiopia began to migrate here in the 1990s, along with refugees from Bosnia. And of course, Mayo Clinic and IBM both attracted many professionals from across the country and the world.

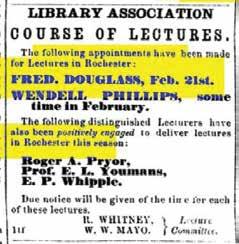

When we take a closer look at the trajectory of Rochester’s history we see a rich and diverse tapestry that is not fully captured in sterile census reports. The myth of homogeneity also isolates Rochester, a city at the intersection of connections between the region, state, nation and world as the home of the Mayo Clinic. It ignores the many visitors, patients, educators, medical professionals and students who traveled to Rochester. A small handful of letters from pioneering Black physicians make passing mention of holiday visits to the Mayo Clinic or hosting one of the Drs. Mayo at their own practices or affiliated universities. One can imagine the exchange of ideas and news that occurred through such transit to and through our city. One of many notable visitors was African-American leader and abolitionist Frederick Douglass who gave a lecture in Rochester in February 1868. The event was advertised as part of the Library Association’s lecture series and listed Dr. W.W. Mayo as one of the organizing committee members. Black suffrage was a hotly debated topic in Minnesota and across the country at the time

A RICH TAPESTRY

of Douglass’ visit.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the Rochester Post and Record often covered brutal lynching, race riots, shootings, trials and racial unrest in the country with a heavy dose of sensationalism and racism. While newspapers contain flaws as sources of historical information, they do signal some of the interests, politics and tastes of the times. Local newspapers from the 19th and early 20th centuries voice opinions on issues like war, partisan politics, Black suffrage, women’s suffrage and Chinese immigration.

Ultimately, as our community grows, so too does our history. What will history say about our city 100 years from now? My hope is that it recognizes the great diversity and contributions of everyday people that make up the fabric of this community. I hope myths of homogeneity are debunked and replaced with real stories of diversity among the people that call this place home. ◆

and STRESS Resiliency EMBRACING THE LESSONS OF CURRENT EVENTS EMBRACING THE LESSONS OF CURRENT EVENTS

BY ROSEI SKIPPER BY ROSEI SKIPPER | PHOTOGRAPHY BY AB-PHOTOGRAPHY.US

FOR MANY AMERICANS THE PAST FIVE MONTHS HAVE BEEN THE MOST STRESSFUL

OF OUR LIVES. From fighting the COVID-19 pandemic to witnessing racial violence and social unrest to enduring financial hardships to caring for children while working from home to worrying about the upcoming election, our nation has collectively experienced mass trauma this year, and there is currently no end in sight.

Worse, many of our most important coping measures are off-limits. This may be the first time many of us have appreciated how vital our close relationships, traveling, going to the gym and gathering to worship are to our wellness.

Dr. Anjali Bhagra is an expert in the study of stress and resiliency. Photo submitted.

STRESS EFFECTS

What is stress exactly, and how does it manifest in our bodies? While the answer is unique for each human, certain bodily changes are universal. Dr. Anjali Bhagra, associate professor of medicine and the chair of diversity and inclusion at Mayo Clinic, is an expert in the study of stress and resiliency. She is the co-developer and co-director of the Resilience and Leadership in Medicine conference GRIT (Growth, Resilience, Inspiration, Tenacity) for Women in Medicine, and she is particularly passionate about how women have been affected by the current pandemic.

“Our bodies are highly evolved to respond to stress, and it’s very good that acute stress triggers the fight or flight response,” says Bhagra. Powerful chemicals flood the body, allowing us to run faster, think quicker and save ourselves and others from threats.

“The problem is if that system gets triggered continuously,” she adds. “The amygdala, our brain’s fear center, grows stronger. Our prefrontal lobes, the rational area of the brain, are bypassed, and we get stuck in a feedback loop.” Chronic stress can lead to high blood pressure, a weaker immune system and higher blood sugar levels, among other health consequences. It also tends to feel terrible.

The past few months have been particularly challenging because we have so little control over what is happening, and no clear sense of when that will change. Data from a current study shows that women are disproportionately affected by the current pandemic, and Bhagra notes that women are underrepresented in positions of power to make policy responding to the crisis.

“It’s clear that women and people of color are more negatively impacted by the current pandemic,” says Bhagra. “These groups hold more caregiving positions, are often juggling child care responsibilities with work and have less access to health care and

other resources.” Intimate partner violence tends to escalate during times of stress, and Bhagra notes that the combination of COVID-19 and George Floyd’s death have made health disparities much more visible.

WELLNESS AND RESILIENCY

Bhagra describes what she calls “The Three Fs” of resiliency: faith (which looks different for everyone), family (work and chosen families included!) and fitness. Her conceptualization of fitness is more inclusive than most—she includes mental, emotional and spiritual health in her definition.

According to Bhagra, thinking about doing something isn’t enough. “It’s important to move beyond a zone of concern into a zone of action.” But that doesn’t have to mean stopping life to work on wellness. Bhagra practices what she calls “four minutes of micro-meditation” a day. She starts her day with gratitude and ends with acceptance. In between she “sprinkles kindness,” with simple acts like dropping off a meal for a quarantined friend or buying coffee for the cars behind her at Dunn Brothers. “Don’t underestimate the power of small gestures,” she says.

“They can have a powerful impact on our own and others’ wellbeing.”

Family educator Nicole Andrews, who is the school readiness supervisor for Rochester Public Schools Preschool, emphasizes the importance of the village mentality—where humans are interconnected , and we do our best when we help each other. “When you do village work, it is for the collective—the whole—and if one of us isn’t succeeding then all of us aren’t succeeding,” says Andrews. “All of us need to be well.”

Andrews believes that wellness and resiliency look different for each person. She encourages her clients to define their own needs and to celebrate their unique strengths and abilities. For herself, that looks like practicing her faith, embracing her family and close relationships and continuing to work for social justice. She says that all of us, herself included, “need to have a well of people, experiences and strength to draw from.”

Andrews draws strength from her relationships with friends and family. Here she hugs her son, Patrick Modo.

ACTION AND GROWTH

Regarding experiences and strength, many of us are confronting systemic racism and internalized prejudice for the first time in our lives. We may be finally acknowledging the

Shah Noor Shafqat finds healing through her art.

tremendous suffering and rage of our Black and brown brothers and sisters, and many feel ashamed for not doing so previously. Combining all this with a pandemic makes it an unusually difficult time in our lives. But it’s one ripe for action and growth as well.

For Andrews, a lifelong social justice advocate, change looks like collective action, increased communication and ongoing equity work. She points out that our BIPOC and immigrant populations have many things to teach us, and that Americans often ignore the tremendous benefits of diversity. She also stresses the importance of getting honest about the hardships that nonwhite Americans experience, both historically and now.

“Real change first starts with acknowledging the truth of our history, no matter how painful,” says Andrews. She emphasizes that we must also invest financially to create real change, saying, "If we ask Black women to educate us about race in America, we need to compensate them in the same way that we pay experts in every other field."

HEALING THROUGH CREATION

Local artist Shah Noor Shafqat’s work has been essential for moving through the many tough moments of motherhood, particularly during the pandemic. Her most recent project “Innocent Predators,” featured at the Rochester Art Center, explores the power that babies exert over their caregivers.

“My work is mostly based on my experience as a mother,” says Shafqat. “Motherhood is more than a full-time job, and art has been a source of healing for me during my journey. Creating leaves me feeling less overwhelmed and less stressed.” Her intricate silk paintings and textile work are beautiful from a distance, and increasingly complex as one draws closer. Her newest exhibit is humorous and honest about the realities of motherhood; adorable babies are depicted with evil features and vampire-like teeth. “It’s okay for us to be truthful about how hard parenthood is and to find the laughter in that pain.”

Although Shafqat has degrees in various artistic mediums, she emphasizes that formal education isn’t a prerequisite to creating. “Art is about problem-solving,” she says. “I feel every woman is capable of doing it. All it takes is practice and exposure.”

MOVING FORWARD

All three women emphasized the importance of taking concrete steps to manage stress right now. For Bhagra, acceptance is an important first step towards action. “In the beginning, many of us were in denial about the pandemic. Many people still are. But the energy we spend denying reality is wasted.” Acceptance allows us to start moving forward, with large steps or small.

For me, that looks like taking a few deep breaths, stretching my body and planning a walk with a friend. Life is different this summer, and it may never be the same. But there are new things to appreciate as well and new ways for us to grow. Be well, friends. ◆