NINJIN

GANKHULEG ASSOCIATE EDITOR-IN-CHIEFRUTH BEKELE CREATIVE DIRECTOR

ZAK ZELEDON DIGITAL DIRECTOR

ANNA WERSHBALE ART EDITOR

ELLA GOLDSCHMIDT, HOLI RAPARAOELINA, SOPHIE CASSIDY, LEXIE FARRIS, CHARLOTTE DAUM, KARA PARK, KIRIN MACKEY, MELANIE LLOYD ART TEAM

BELLA ORTIZ-MILLER BEAUTY EDITOR

BREYONNA ROCK, DANELL MONTES, EMILY HAN, JASMINE TURKSON, VICTORIA KIM, JACKLYN GOLLAYAN, MIA K. REGINELLI, NEVAEH GALLUCCIO BEAUTY TEAM

LIVIA MARTINEZ DIGITAL EDITOR

AVISHKA BOPPUDI, CLARA WHITNEY, FAIZA ISA, GAVIN AQUIN HERNANDEZ, GWEN SARGENT, INDIA TURNER, KATIE FITZGERALD, SOPHIA MAURO DIGITAL TEAM

KATIE TAGUCHI, SASHA SKLAR FEATURES CO-EDITORS

AZRAF KHAN, CAROLINE LEIBOWITZ, LINDA LI, SOFIA WARFIELD, SOLEIL GARNETT, HARPER MCCALL, SYDNEY SHOULDERS, LILLY TANENBAUM, RICHA ZADE FEATURES TEAM

ALEXA CARMENATES, MONICA BAGNOLI, ANNA VAN MARCKE, LIVIA MARTINEZ, HENRY NETTER, SASHA SKLAR, CAROL GRACE ANDREWS, EM EBALO, HANNAH MONTALVO, CLARA WHITNEY, KATIE FITZGERALD, HOLI RAPARAOELINA LAYOUT TEAM

HENRY NETTER MARKETING EDITOR

SAM GASTEIGER, SHELBY MUNFORD, ELISE NORQUIST, CAROL GRACE ANDREWS, ISAIAH NUÑEZ MARKETING TEAM

DAWN BANGI, GARRETT GOLTERMANN, HANNAH MONTALVO, ETHAN QIN, RACHEL PERKINS, JORDAN LERNER, AVA NOCE PHOTO TEAM

ANNA VAN MARCKE, ALEXA CARMENATES PRODUCTION CO-EDITORS

CARSON BELMEAR, INAYA MIR, MADELINE PUDELKA, REILLY JACOBS, SHARON SANDLER, SAIRA YUSUF, AVA HAGEE, HANNAH NIEMAN PRODUCTION TEAM

JESSICA SIGSBEE, ABBY INDARSINGH, SIMIYA MCEACHIN, EMILY CAMPBELL PUBLIC RELATIONS TEAM

BELLA GRACE FINCK, BLAZE BANKS, CALEB STREAT, JENNA ASHTAR, LACE GRANT, ERIN CHAN, LAILA HAMER, HANNAH MCMINN, DYLAN DAVID, NIKITA CHELLANI, ATTICUS GORE STYLE TEAM

TIFFANY NGUYEN WEB EDITOR

CHEYENNE HWANG, ROSHNICA GURUNG, GELILA YIMTATU, EM EBALO, KAILYN PUDLEINER, CHIDI AKUNWAFOR WEB TEAM

MONICA BAGNOLI PHOTO EDITOR

Here we are again, another amazing publication released by ROCKET. Since joining my freshman year on the style team, I always wondered what it would be like at the top of the executive board. Now as a senior, being Editor-in-Chief is beyond what I ever imagined. ROCKET has truly been a resource for me as a visionary and innovative outlet while attending William & Mary. ROCKET is a space where I can be myself and express who I am along with other like-minded and innovative students.

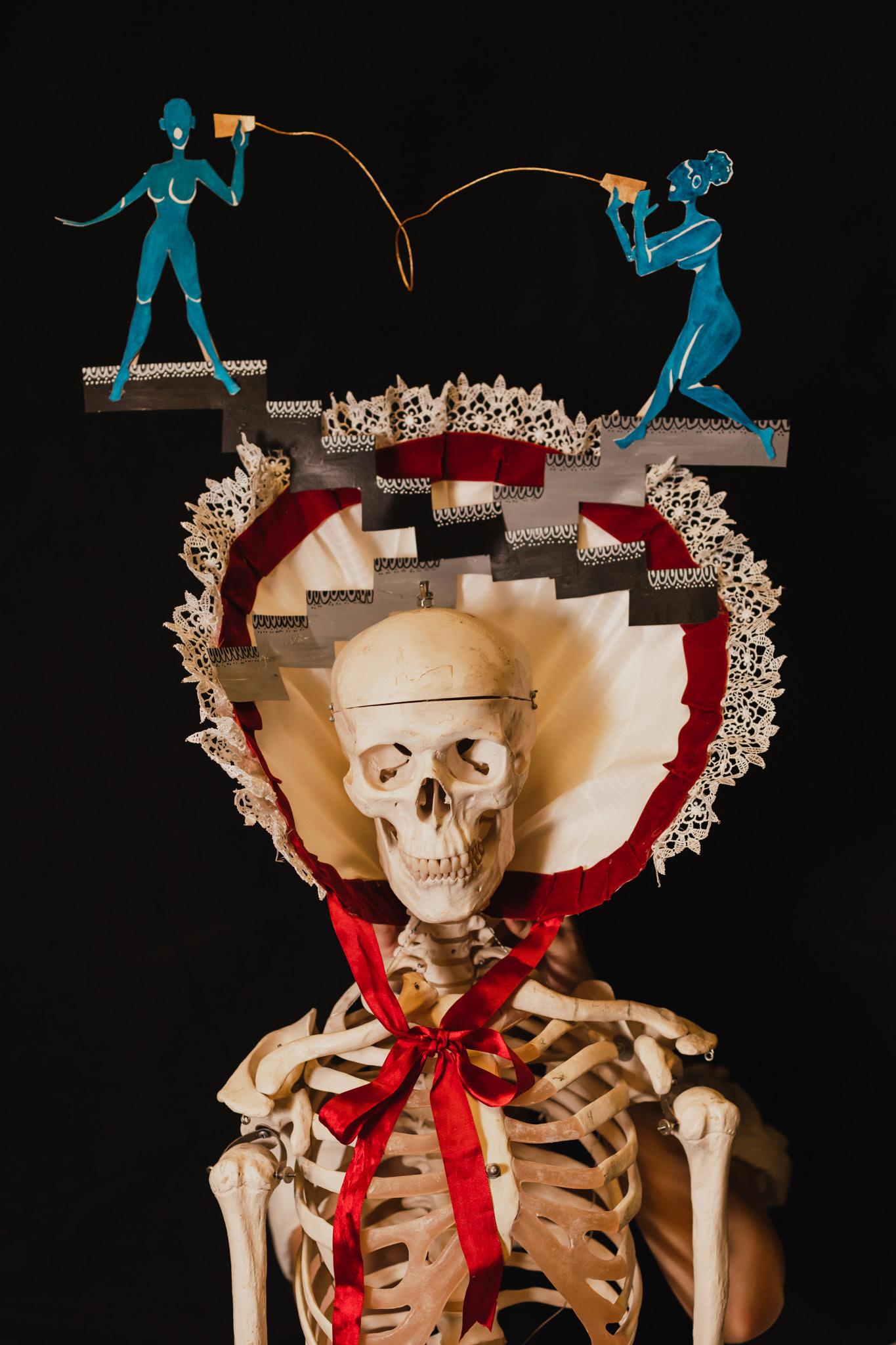

Combining my creative vision with the ideas and effort from over 80 staff members has produced an elite fall/winter 2022 release we title as “ROCKET Renaissance.” This semester we wanted to put emphasis on modernizing our original style and fusing the old with the new. There’s more focus on our features and art pieces this time to demonstrate how experimental we truly are. Our cover photos on the front and back for this issue show handmade bonnets created by our art team members demonstrating both

our theme and originality. Throughout the rest of the magazine, our content is artistic, imaginative, and daring. Thank you for picking up this copy. I anticipate that as you look through this issue of ROCKET you are inspired and understand our efforts put into each and every page.

When I first walked into my Emily Dickinson class fall semester of my sopho more year, I didn’t know much about the prolific poet. I knew what people had told me: she was an elusive woman in a white dress, a recluse who holed her self up in her bedroom with only her poems as company. And I knew Hailee Steinfield played her in the recent Apple TV show. But that was about it.

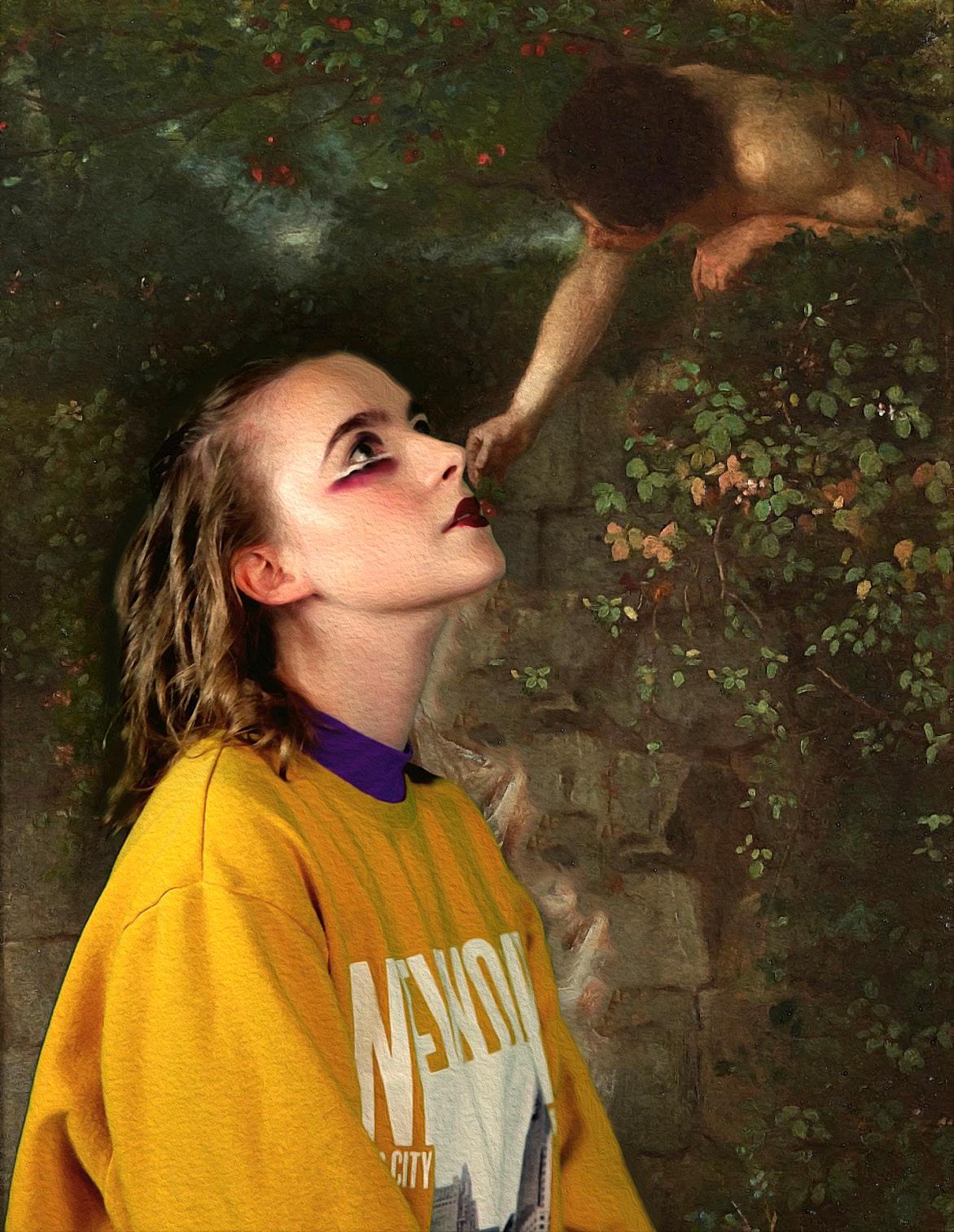

Class after class, Dickinson shattered all of my expectations. Poem after poem, I be came enamored with her words and her life. There was so much about her that I never expected - she was unapologetically ambitious and witty, she was a wonderful baker, and she was earnestly devoted to her flower garden. Something about her and her poetry struck me in an indescribable way. I read “Not knowing when the Dawn will come, I open every Door,” and it felt like the words were sinking into my skin. After the semester, I immediately started watching Dickinson, the TV show about the poet that aired in 2019. The show doesn’t portray Dickinson as the agoraphobic, meek spinster that she is often described as. Instead, Steinfeld’s outspoken Dickinson takes opium and uses 21st century slang against a modern soundtrack.

modeled by SARAH IBRAHIM

modeled by SARAH IBRAHIM

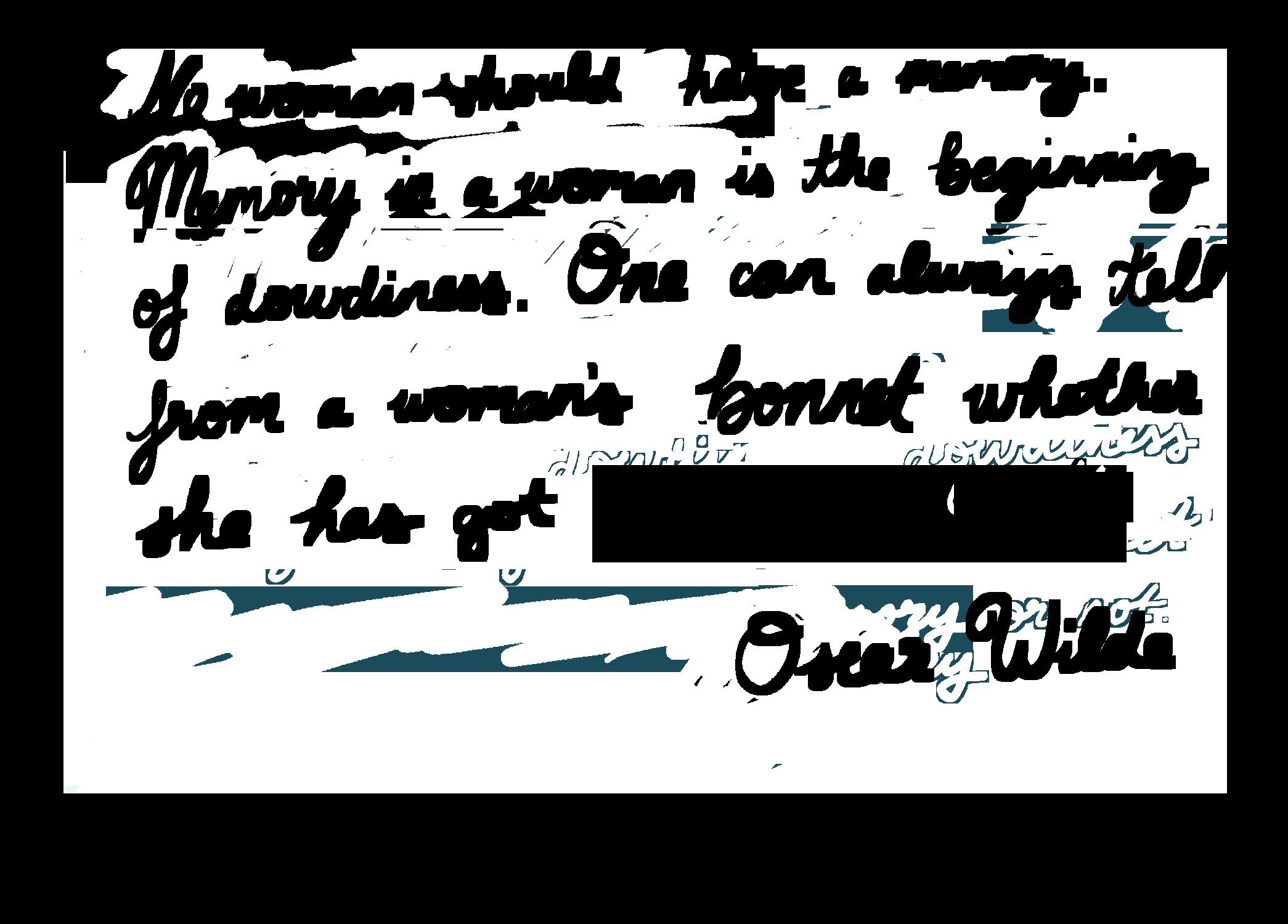

The show got me thinking about other modern adaptations of iconic female writers and characters. In the past few years, we’ve seen adapta tion after adaptation - Dickinson, 2019’s Little Women, 2020’s Emma, 2022’s Per suasion, 2023’s Em ily, and more. Over the summer, I binged Anne with an E, the Netflix series based off of L.M. Montgom ery’s Anne of Green Gables, and I trea sured every second of it. I found myself tearing up during al most every episode, feeling a mysteriously profound connection

to this ebullient, quick-tempered Canadian girl. Many modern topics are brought into the show, which is set in the late 19th century, including sexual assault and racial profiling.

It seems as though we have a particular interest in bringing these contemporary is sues into classic literature. But where does historical accuracy come into play? Was Emily Dickinson actually vehemently against slavery, as portrayed in the 2019 show? Would a young girl living in a small Canadian town in 1896 really stand up against sexual harassment? Why is it so important to us for these iconic writers and characters to reflect and validate our contemporary values? We continue to reimagine and reinvent these women so that they transcend time, so that they belong in our modern world.

There are both positive and negative examples of this. I adored Dickinson and Anne with an E. Dickinson’s anachronisms felt inventive and en tertaining, and Anne with an E man aged to appropriately incorporate modern issues into its plot in a way that felt natural. Other adaptations have been less successful, though. For instance, 2022’s Netflix adapta tion of Persuasion by Jane Austen fell flat in many ways; the film’s at tempts to contemporize the great classic novel end up undermining its characters and story. It’s difficult to balance the classic and the mod ern, but regardless of the success and failures of various adaptations, there’s no denying that we continue to try to bring our favorite literary women into contemporary contexts.

We search for a place for Dickinson and the Brontës and Austen in our modern day. We want to imagine them as women we could sit down for coffee with, or women we would see in our classes. We want to relate to them. More than anything, I think these modern adaptations represent how intensely we ache to be understood. We want to know that people like us have always existed, and we want to know that our longings are universal longings. We find comfort in knowing that our feelings have eclipsed time. I think that’s the beauty of literature - particularly literature by women -

in that it makes space for us in the world. These modern adaptations allow us to recognize and value the women who have come before us while also looking forward at what’s next. Revisiting female voices from the past reminds us of the timeless power of female-centered stories. Some parts of the female experi ence will always remain universal. These women help us to feel less alone, reminding us that our pain and our pining and our passion has been felt for hundreds of years.

And I think it’s a two way streetwhile these women can do so much for us in helping us feel less alone, there’s something we can do for them, too. By placing these women in modern contexts, in many ways, we’re liberating them from the constraints of their time period. We’re amplifying their voices and allowing them the freedom that they’ve always deserved. The show Dick inson unapologetically portrays the passionate, romantic relationship between Emily and her sister-inlaw, Sue. Austin Dickinson, Emily’s brother and Sue’s husband, had a mistress who tried to erase all trac es of Emily’s love for Sue from Emi ly’s letters and poems after she died.

The show undoes all of this bitter work in liberating this 19th century queer couple, allowing them tenderness and safety and the space to exist contentedly. In several ways, including her unconven tional poetry, Dickinson seemed like she didn’t quite belong in her time period. By allowing her ac cess to the 21st century, we’re freeing her and giving her a place to belong. I would like to imag ine that Dickinson herself would love how strange and passionate and rapturous the show is.

There’s so much power in pulling these women into the present day. I hope we never stop bringing con temporary takes to writers and stories and characters of the past. The focus isn’t on unerring historical accuracy, but instead on how real these women feel. It’s scary to think that a society that existed a hun dred years ago is similar to our society today, but it can also be comforting. The renaissance of these ad aptations creates an incredibly freeing space for women, as it shows us that there’s always been space in the world for us. Across hundreds of miles and hundreds of years, there’s someone who feels exactly as you do. That’s why I loved Dickinson when I first read her last year; I’m sure I’m not the first to feel as though there’s a piece of her in me, and maybe a piece of me in her. And that’s a beautiful feeling.

production by ANNA VAN MARCKE, ALEXA CARMENATES, AVA HAGEE beauty by BELLA ORTIZ-MILLER, JASMINE TURKSON, BREYONNA ROCK, DANELL MONTES, EMILY HAN, MIA K. REGINELLI style by LEYAH OWUSU, DYLAN DAVID, LAILA HAMER, NIKITA CHELLANI, ATTICUS GORE, HANNAH MCMINN, ERIN CHAN

production by ANNA VAN MARCKE, ALEXA CARMENATES, AVA HAGEE beauty by BELLA ORTIZ-MILLER, JASMINE TURKSON, BREYONNA ROCK, DANELL MONTES, EMILY HAN, MIA K. REGINELLI style by LEYAH OWUSU, DYLAN DAVID, LAILA HAMER, NIKITA CHELLANI, ATTICUS GORE, HANNAH MCMINN, ERIN CHAN

modeled by RAGAN ARRINGTON

modeled by RAGAN ARRINGTON

photography by RACHEL PERKINS, JORDAN LERNER production by ALEXA CARMENATES, ANNA VAN MARCKE, CARSON BELMEAR, SHARON SANDLER, INAYA MIR, SAIRA YUSUF beauty by BELLA ORTIZ-MILLER, JACKLYN GOLLAYAN, DANELL MONTES, EMILY HAN, MIA K. REGINELLI style by LAILA HAMER, LEYAH OWUSU, ERIN CHAN, CALEB STREAT, BLAZE BANKS, HANNAH MCMINN, DYLAN DAVID

photography by RACHEL PERKINS, JORDAN LERNER production by ALEXA CARMENATES, ANNA VAN MARCKE, CARSON BELMEAR, SHARON SANDLER, INAYA MIR, SAIRA YUSUF beauty by BELLA ORTIZ-MILLER, JACKLYN GOLLAYAN, DANELL MONTES, EMILY HAN, MIA K. REGINELLI style by LAILA HAMER, LEYAH OWUSU, ERIN CHAN, CALEB STREAT, BLAZE BANKS, HANNAH MCMINN, DYLAN DAVID

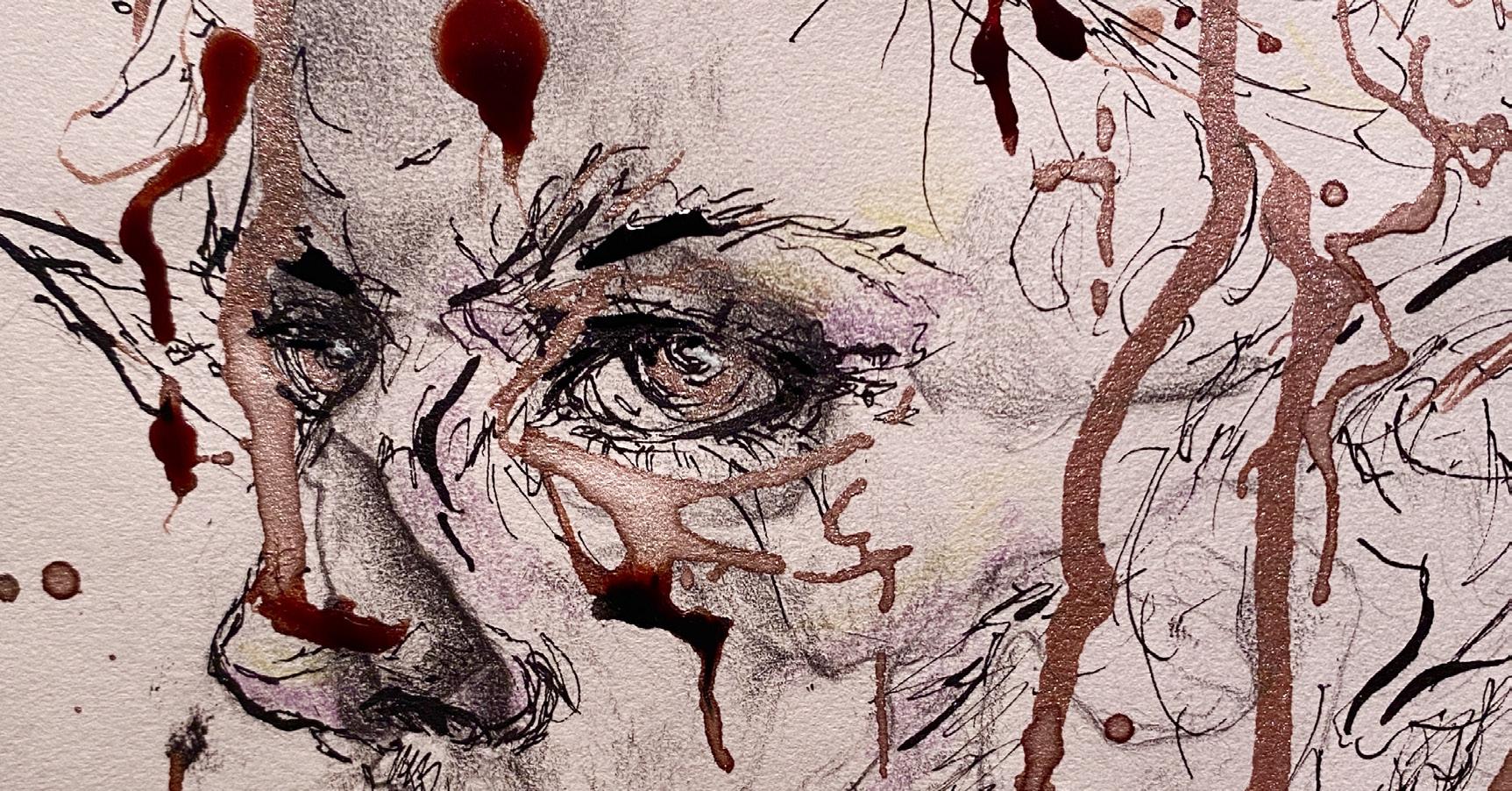

Finding yourself upon an uncanny, dreamlike landscape oftentimes evokes a sense of unsettling familiarity. Graveyards shrouded in mist, hiding the moon behind filmy clouds and reflecting across glossy tombstones; dimly-lit corridors breathing and bending as you walk past foreboding portrait paintings; and weath ered cityscapes that are framed by antique lamplight and discolored brick all evoke a sense of unnerving comfort. Why do these spaces feel so foreboding, yet seem easily placed to an experience you’ve had before? To me, it is because these spaces embody the Victorian Gothic’s rebirth into twenty-first century culture.

The Victorian age embodies nineteenth century British society’s rapid change. Charles Dickens’ famous quote, “[i]t was the best of times, it was the worst of times,” reverberates in the Victorian era’s historical legacy. Coping with rapid societal change largely influenced Victorian Gothic fiction–a genre defined by its use of the supernatural, taboo themes, and un canny settings. The genre allowed Victorians to be vulnerable and question developing societal constructs through fictional bodies that haunted the world they lived in. Even today, novels like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights, and Bram Stoker’s Drac ula find their ways onto bookshelves and into the darker, unexplored regions of our minds.

The lingering effects of both Gothic fic tion and the Victorian age creates a discernible aesthetic that many of us use to find unsettling comfort in uncanny settings. Graveyards be come a plausible place to find Victor Frankenstein mourning his creature’s victims; long, per sonified corridors seem to be the place to find Catherine Earnshaw fleeing from Edgar Linton and into the unattainable grasp of her fated lov er, Heathcliff; and weathered cities mirror the aged cobblestone towers in Transylvania. Our familiarity with the Victorian Gothic’s impact de fines our interpretation of spaces plucked out of darker nineteenth century British aesthetics. The Gothic’s influence extends farther than these novels and their impacts on us. Particularly,

the Gothic influences macabre, haunting set tings in twenty-first century visual art. Tim Bur ton, a well-known filmmaker, revives the Gothic aesthetic in many of his popular films. His use of Gothic aesthetics and themes heightens our awareness of the era’s tropes, fueling our famil iarity with themes that extend beyond centuries.

Tim Burton, like the Victorian Gothic, has an easily-placed aesthetic. Hollowed features, animated, jagged structures, and haunting, yet lighthearted themes categorize the popular film maker’s artwork and link his pieces directly to the Gothic aesthetic. For example, The Corpse Bride is one of my favorite Tim Burton movies. It may just be because I love Wuthering Heights, but, nonetheless, it remains a focal film from my childhood. There was something weirdly roman tic about Victor falling in love with a literal ‘Corpse Bride’ and following her to the underworld. It was also extremely satisfying to watch Emily, the fe male protagonist, exact revenge and encourage the male protagonist, Victor, to marry Victoria. As a child, it was probably concerning that I en joyed this film so much. I look back on my fas cination and remember the haunting sense of grandeur that captivated my attention each time I rewatched the film. The monochromatic setting, character illustrations, and broad themes invited me into a world in which darkness and change could produce a ‘happy ending.’ Reviving the Gothic in twenty-first century society allowed me to understand the changing world around me. Weirdly, it helped me find silver linings in demanding situations that I would encounter throughout my life. The spectrum of literature, art, and aesthetic meet in an uncanny Burton aesthetic that many of us are familiar with. Reviving the Gothic allows us to bridge the light and dark ness that we all still encounter today. However, the Gothic era’s modern portrayal is not always defined merely by aesthetics–especially when it comes to examining historical discrimination that influences the exclusionary display of the Gothic by popular artists, both past and present.

modeled by SUMAYYAH YASIN, ADELINA O’CON, BLAZE BANKS

modeled by SUMAYYAH YASIN, ADELINA O’CON, BLAZE BANKS

Though many of us have a particular image of what the Gothic aesthetic is, we tend to neglect historical discrimination and exclusion that the Gothic era perpetuated. Literature, for example, centers around white characters that interact with ‘othered creatures’ and corporeal forms that modern literary scholars interpret as commentary on race relations. Adhering to a sense of ‘oth ering’ perpetuates history’s dismissal of minority groups, which embodies longstanding discrimi nation displayed through the Gothic aesthetic. Attitudes evident in literature reflect the age’s shift from exploitation and discrimination of racial groups as they moved towards emerging abolitionism in the beginning of the century. Dual-coded, ‘othered’ figures thus created an inherent gap between whiteness and representing the diversity the age would embrace in the latter part of the nineteenth century. These themes have manifested into twentieth-century Gothic aesthetics, es pecially when it comes to Tim Burton. Specifically, Tim Burton has stated that his aesthetic is best illustrated by using a cast of white characters. In fact, the only time Burton diverts from his racist display of the Gothic is through his character Oogie Boogie in The Nightmare Before Christmas. Ken Page, Oogie Boogie’s voice actor, is one of the few Black (voice) actors that is included in Burton’s works. Even then, Oogie Boogie is racialized only through his voice; his character is not awarded the humanized Gothic aesthetic many white characters are given. Though The Night mare Before Christmas does include human families from diverse backgrounds, Burton adheres to racial stereotypes that are heightened by Oogie Boogie’s lack of physical, diverse characterization. His choices reverberate throughout many of his films, as his well-known characters influence our association of whiteness to the Gothic aesthetic. Tim Burton’s racist ideology thus raises a larger question when examining the Gothic’s implementation in the twenty-first century.

Reviving the Gothic in the twenty-first century gives us the opportunity to unlink the longstanding association between whiteness and the era’s aesthetic. Implementing techniques such as colorblind casting, subverting racial stereotypes in particular roles, and breaking canonic associations between ‘light’ and ‘dark’ allows the twenty-first century to include adopted, diversifying techniques to change our perception of the Gothic era. Unlinking whiteness and the Gothic aesthetic ultimately incorporates the history of individuals that were neglected during the era and provides an oppor tunity for their voices and narratives to be seen in modern, Gothic-inspired art. Reviving a diverse Gothic aesthetic thus incorporates a rejection of historical discrimination and an illumination of the twenty-first century’s inclusivity. Beauty, like the Gothic era, comes in many forms. It is time we embrace the diverse, twenty-first spectrum of beauty through our revival of the Gothic aesthetic.

“The whole series of my life appeared to me as a dream; I sometimes doubted if indeed it were all true, for it never presented itself in my mind with the force of reality.”

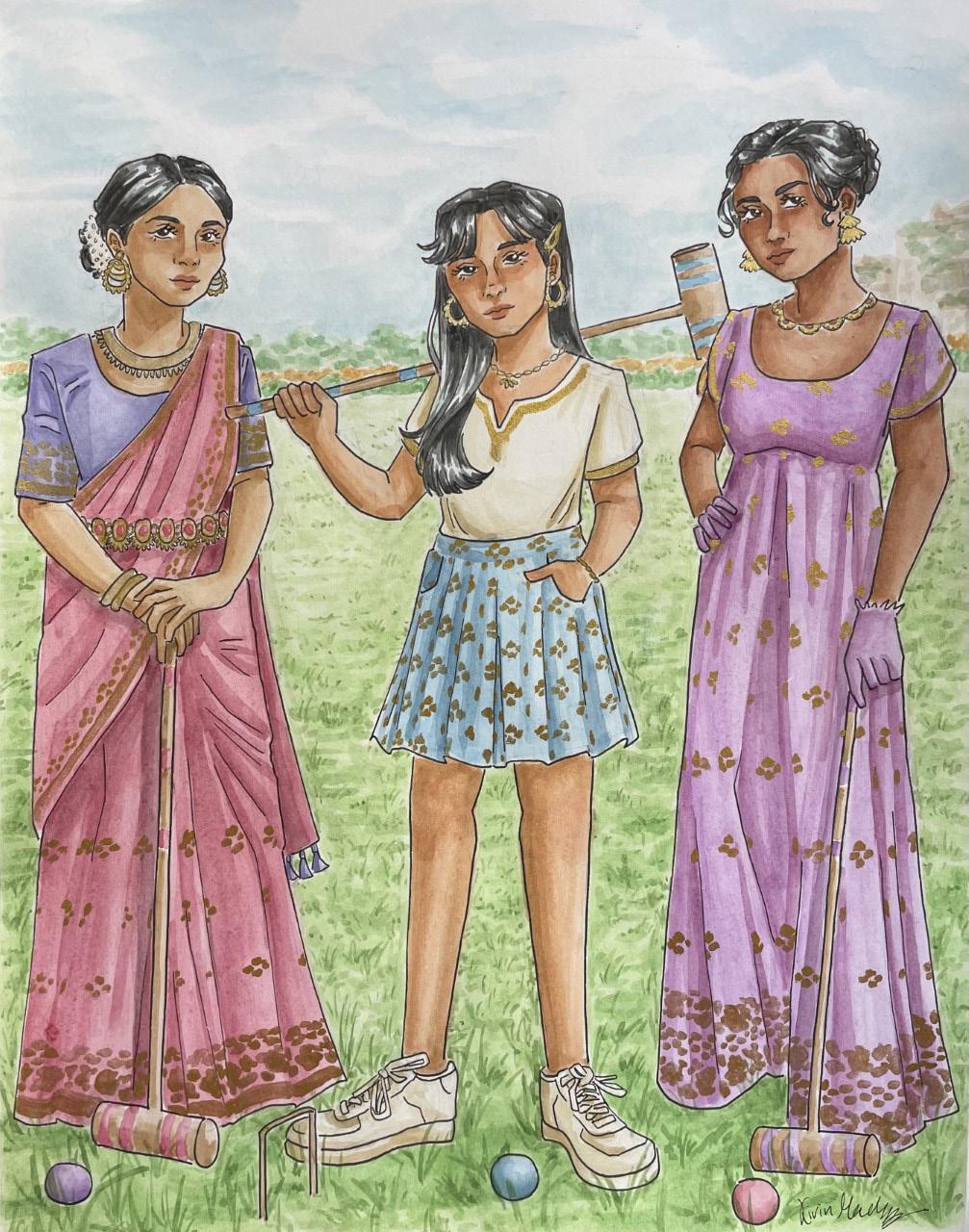

I’ve spent most of my life looking for reflec tions of myself, but turning up with blurry, distorted ghosts of the girl who should be standing in front of me. In coffee shop windows, the smudged mirrors at Sephora, the people I pour my heart into. But more importantly, in the myriad of movies, books, and tv shows I con sume. I must admit I’ve indulged in my fair share of “Which Victorious character are you?” Buzz Feed quizzes, but there’s always an element of irony for me — why was I trying to fit myself into a space that has never made room for me? It’s ironic that a country built by such diverse cultures is centered around systematically si lencing those very same voices. This country is far from the “melting pot” it claims to be, and nowhere is this narrative of exclusion more ev ident than in Hollywood — a brutally accurate interpretation of how we see our society. The kinds of people and stories we showcase — as well as the ones we don’t — are all influenced by our conception of our world, but not what it actually is. This reflection has been skewed for far too long because the industry has excluded some of our most central voices — people of color. The paltry handful of token diversity characters are often reduced to stereotypes so their cultures are all but erased. Watching films with Indian characters is usually so uncomfort

able that I avoid it altogether. I suppose after a lifetime of witnessing Hollywood skew you into a twisted cliché, it’s hard to watch without a sense of dread, waiting uncomfortably for when they inevitably screw it up. It’s like hand ing your very delicate science fair diorama to someone and saying, “here — look at this re ally fragile representation of my culture and see how very complex it is — but please be careful!” Hollywood all but threw it in a wood chipper, set it on fire, and roasted marsh mallows over it. Until I watched Bridgerton. I remember sharpening my criticism knife when I first watched Season 2, ready to carve up these characters who seemed like me but would eventually fall short. I spent the whole season waiting for that moment. Tore it apart trying to find some flawed construal of my culture that Hollywood had subscribed to for decades. Instead, I ended up with two gorgeous, nuanced, thoughtfully-written char acters who deserved the spotlight not only because they had been denied it for far too long, but also because they were so captivating that they simply demanded it. It was like I’d spent 20 years of my life looking for my reflection in the dirty warped mirror of a strip mall thrift store, and suddenly someone had taken me to Saks Fifth Avenue and showed

me how the rest of the world saw themselves. So many people have had a similar experience with the show — both Indian people and other POCs alike. Growing up watching my culture manifest itself as characters like Bal jeet from Phineas and Ferb or Ravi from Dis ney’s Jessie made me feel like people of col or just weren’t part of the American cinematic experience. It’s hard to cast a POC charac ter without falling into harmful stereotypes or white-washing them, but instead of putting in some extra work, Hollywood often resorts to either option, and we end up with Scarlet Johanssen playing an Asian character in Ghost in the Shell, or Kunal Nayyar playing the stereo typical awkward nerd in The Big Bang Theory. Bridgerton, on the other hand, was revolution ary because it portrayed people of color as normal— not working overtime to represent their culture and earn a place on the screen, not stereotypical or watered-down, but whole complex characters that are just as well-writ ten as their white counterparts. Instead of being vessels of their entire culture, Bridgerton gives its POC characters the space to be emotional, mature, and nuanced without di luting their culture. Kate and Edwina are not empty characters clumsily clad in some com modified version of South Asia — the threads of their culture are woven together so thoughtfully with their ambitions and obstacles that

one can’t help but be completely mesmerized by them. The hint of Indian accents in their impeccable British, the Indian jewelry paired with their Regency-era gowns, even the Hal di ceremony before Edwina’s wedding, com plete with marigolds and an orchestral ren dition of “Kabhi Khushi Kabhi Gham” — the attention to detail made me feel the same as I did when I first listened to Raveena’s mu sic or read Rupi Kaur’s poetry: I had finally seen a clear reflection of myself. These are the characters we have waited decades for. The ones who showcase their culture proudly, who foster an intimate connection with the audience, and who ultimately create a much more genuine celebration of Indian culture. Speaking of music, Bridgerton’s soundtrack mirrors the series’s reimagined Regen cy society setting. The orchestral covers of “thank u, next,” “Material Girl,” and “Wildest Dreams” show how modern ideas like fem inism and racial equality influence an era where racism, sexism, and classism were de pressingly common, creating a “post-racial” fantasy of the Regency era. Bridgerton is an alternate history, not a revisionist one — its setting may be utopian, but it does not aim to erase the decades of trauma endured by minorities during that time period. Instead, this reimagined society forces a comparison with the “real” timeline

— what was Regen

“Bridgerton, on the other hand, was revolution ary because it portrayed people of color as nor mal— not working overtime to represent their culture and earn a place on the screen, not stereotypical or watered-down, but whole complex characters that are just as well-written as their white counterparts.”

cy-era Britain really like for minorities? This obvious historical inaccuracy highlights our timeline’s British imperialism, for example, as well as South Asia’s toxic fascination with colorism that exists even today – this is why casting darker-skinned Indian wom en to play Kate and Edwina is so significant. As much as I love it, Bridgerton’s theme of represen tation and in clusion falls short in many ways, espe cially LGBTQ+ representa tion. While the first season did feature Benedict’s discov ery of a secret relationship between two men, the arc was ultimate ly disappoint ing because it swerved so sharply on creating an LGBTQ+ character that would unde niably elevate Bridgerton ’s diversity. If the show can pair Black and South Asian rep resentation with well-written plot arcs for Daphne and Anthony, and hint at the begin ning of a complicated romance between El oise and Theo that could tackle the show’s glaringly obvious classism, then Benedict deserves a character-building challenge as well. Perhaps he could be challenged to ex plore his sexuality with people of color, pro viding some much-needed intersectional

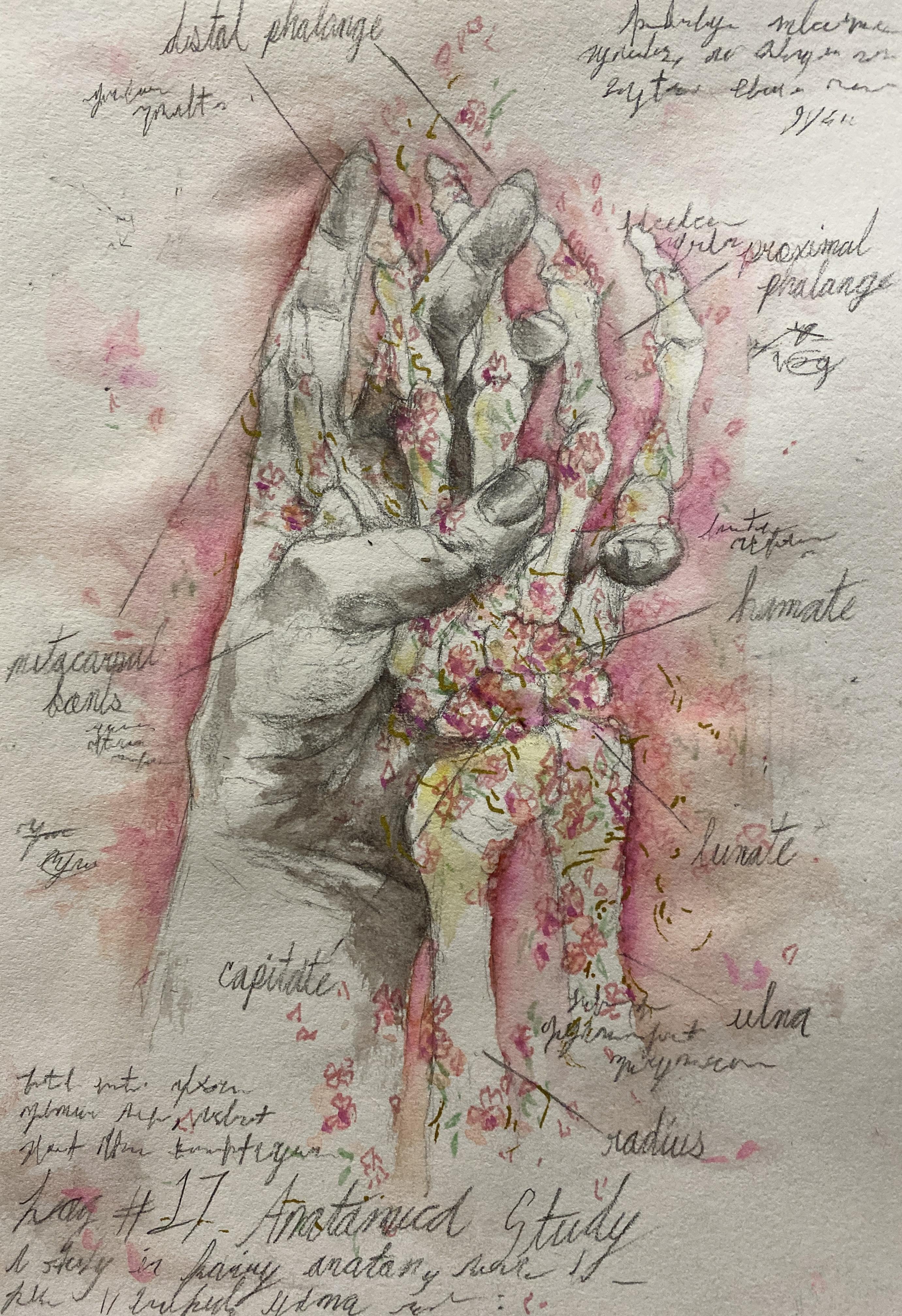

art by KIRIN MACKEY

art by KIRIN MACKEY

representation. It would create yet another more accurate reflection for so many of us (myself included), and reinforce the notion that people of color are defined by more than just their culture. But that’s the beauty of setting a precedent: it gives us the foundation for future works to build on. Bridgerton is certainly not perfect, nor is it meant to be. It is just an example of POC representation done well. We can’t expect one piece to shoulder the entire burden of representation in the media, but Bridgerton paves the way for more such works to come — the plethora of popular films and TV shows cel ebrating minorities that have popped up since Bridgerton’s initial suc cess is a testament to the undeniable signif icance of precedents. For now though, I am beyond grateful that I can look into the mirror of mainstream media and finally see nothing less than a clear au thentic reflection staring back at me. After decades of misrepresentation, it’s as though Hollywood finally got my message: I am not just some offensive stereotype. I am not your chauffeur, your IT intern, your thick-ac cented doctor, your spelling bee winner, your yoga instructor, your token diversity character, your ridiculously skewed interpretation of a culture so beautiful, vibrant, and beyond your com prehension. I am a woman of color— get it right or move over so I can show you how it’s done.

have waited decades for.

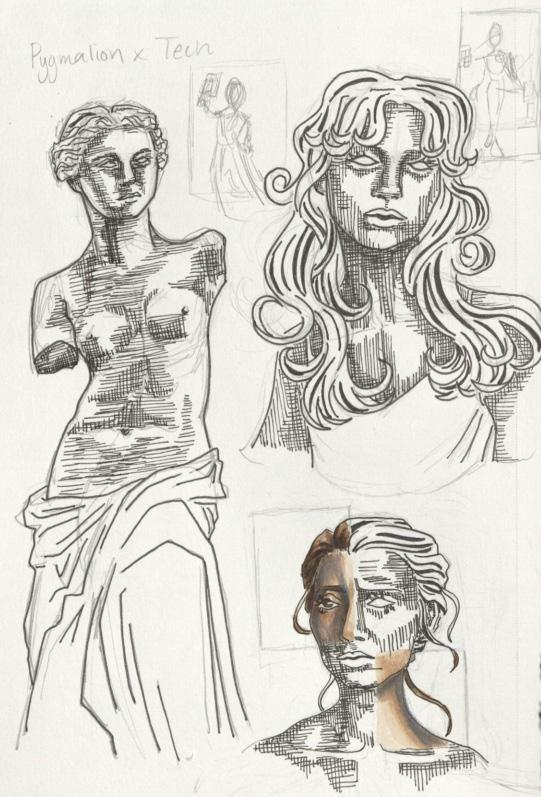

The renaissance period brought about a pas sion for realism, the imitation of nature, and body aesthetics. In the modern age we have the tools to create art that imitates life in such a real way that it is becoming increasingly difficult to distinguish the two. We are able to create impossible realities of life through fil ters, photoshop, and AI; and we are ever more tempted to choose the ideal over the real. This piece begs the question: are we entering an era where life will strive, most likely in vain, to imitate art? If so, what does that mean for us as we move forward?

I have three pieces of clothing with the iconic Levi’s tag on them: a pair of jeans from a recent collaboration between Levi’s Jeans and Target, a thrifted pair of pants, and a jacket I stole from my mom. It is a testament to the durability of Levi’s denim that a jacket my mom purchased decades ago would become a staple of my wardrobe. It is this durability that allowed Levi Strauss to reinvent workwear in America by creating a pair of jeans that became popular with miners for its creative use of fabric and rivets during the California Gold Rush of the 1850s. In fact, the garment industry seems to have reinvented itself many times over in many different ways - but it cannot truly have undergone a reinvention if its methods of exploitation and production re main the same as they did when Levi’s first found success.

In recent centuries, arguably the most pivotal inven tion in the garment industry was the sewing machine, which began gaining popularity in the 1850s - no reinventions would have been possible without it. Before the sewing machine, clothing could not be produced en masse. Most clothing was made locally by a tailor or seamstress, and took hours to make - a man’s shirt would have been measured specifical ly to him, and could take around 14 hours to complete by hand, but even an early sewing machine could have made this shirt in an hour. The first clothes to be made en masse were soldiers’ uniforms. During the Civil War, soldiers need ed uniforms of the same design and fabric in large numbers. For the first time, there was a way to produce these matching uniforms quickly. And so the garment industry was reborn.

Or, it would have been - but something was missing: workers. In 1880, most American clothing was hand-sewn. By 1890, most American clothing was made and purchased ready-to-wear: this was a complete reinvention, made possi ble by both new technology and new workers. New technol ogy is good, but it is nothing without people to use it. Those people came, finally, in the millions, carried over on boats from places in Europe where they were politically and socially un wanted in the 1880s. Millions of these people were Jews from Eastern Europe, like Levi Strauss. Remarkably, these Jewish immigrants were the perfect fit for what would show itself to be a horribly imperfect job: the creation of ready-to-wear clothes.

These immigrants settled in urban areas, where, coinciden tally, the garment industry was in need of workers. By 1887, seventy-five percent of all gar ment workers in New York City were Jewish immigrants. Al though the conditions for these workers were better in America than they had been in Europe, workers rights were practically nonexistent. Days were long, rooms were crowded, pay was low. Workers were exploited by supervisors, who ran factories with essentially no regulations or oversight from the govern ment or public opinion.

As these conditions were exposed to the public through a series of tragedies in gar ment factories, workers’ rights evolved and the garment indus try seemingly reinvented itself for the better. In 1911, tragedy struck at The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, a garment factory in Manhattan. It was staffed, like so many other garment facto ries, by underpaid immigrant women. The owners of the factory manipulated and ignored safety codes to increase their profit, and these manipulations meant that when the factory caught fire, the women working high-up in the building had no way to escape alive. 146 people were killed. From the ashes of this tragedy, advocates reinvented labor legislation and the protections of garment workers that allowed them to leave behind, albeit slowly, the factories they had reinvented.

At first glance, this is in fact a reinvention for the better. But when European-Ameri can immigrants and their descendents emerged from dark and crowded factories and closed the doors securely behind them, the factories needed to fill their seats. European immigrant workers have been replaced by overseas workers, many of whom work for large corpora tions who outsource production to poverty-stricken places in Asia. Much like the immigrants of a hundred years ago, the workers in these areas have no choice but to accept the low pay and the inhumane treatment they receive because of a lack of other opportunities.

New technologies and relocations have ensured that someone is always los ing in this century long cycle of exploitation.

In the 1990s, when my mom bought her jean jacket, 50% of clothing worn in America was made there. Today, that number is less than 5% and in 2003, Levi’s closed its final factory in the United States. There’s a chance my mom’s jean jacket was made in the United States, but Levi’s jackets are now made entirely overseas under poor working conditions. Workers in some of these countries have struggled to organize and advocate for their safety, just as Jewish-American immigrants did in America over a century ago.

In 2012, 101 years after the Triangle Shirt waist Factory, 112 garment workers were killed in a fire in Bangladesh. Eerily similar to the conditions that created the tragedy in Manhattan in 1911, the factory workers were forced to endure unsafe con ditions that left them no way to escape the fire alive.

“The garment industry did not reinvent itselfit simply shifted its reach and reconfigured its systems.”

In the wake of this fire and what has sadly be come a growing number of tragedies and injustices sur rounding the modern-day garment industry, large com panies like Levi’s have promised to reinvent themselves once again. But these promises have not come true yet, nor do they mean anything until they have.

A truly positive rebirth of the garment industry will not require people to die or live inhumanely so clothing can come to life. In fact, any sort of rebirth would have to include a drastic change in methods, workers, and technology. But the only thing that seems to have truly been reinvented is technology. Modern sewing machines don’t look anything like they did 150 years ago, but the treatment of the people who use them is eerily similar.

We look at technology as a means to progress society into the future, but that doesn’t mean it can’t transport us to the past. It brings the past back to life, revealing the creativity hidden under the veil of history. It shows us that we are products of that creativity, yet further sculpting it into new shapes and perspectives. By doing so, technology intertwines us with the history created now, making a new block of clay future generations can sculpt with and experience a rebirth of their own.

photography by MONICA BAGNOLI beauty by BELLA ORTIZ-MILLER, NEVAEH GALLUCCIO, EMILY HAN, BREYONNA ROCK, JASMINE TURKSON production by ANNA VAN MARCKE, SHARON SANDLER, INAYA MIR, REILLY JACOBS, CARSON BELMEAR, AVA HAGEE

photography by MONICA BAGNOLI beauty by BELLA ORTIZ-MILLER, NEVAEH GALLUCCIO, EMILY HAN, BREYONNA ROCK, JASMINE TURKSON production by ANNA VAN MARCKE, SHARON SANDLER, INAYA MIR, REILLY JACOBS, CARSON BELMEAR, AVA HAGEE

modeled by ABDELRAHMAN OSMAN, SAMIRA RAHMAN, ZYANNAH MALLICK, AWAB GIDDO, MUHAMMAD RATHORE, SALMA AMROU

modeled by ABDELRAHMAN OSMAN, SAMIRA RAHMAN, ZYANNAH MALLICK, AWAB GIDDO, MUHAMMAD RATHORE, SALMA AMROU

Despite the Harlem Renaissance being most re membered for its jazziness and brevity, much of the art of this era is reflective and complex, investigating problems that people today are still looking to answer.

In school, all I learned of the Harlem Renaissance was the music of Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong. Later in life did I come to understand how it was an era of unapologetic and unprec edented mainstream Black expression.

I learned how Black identity was re claimed and reinforced for later genera tions to proudly emulate. Black joy could be found in the dances of Josephine Baker and the ease of Billie Holiday’s voice. Accenting all this progress was a shift in women’s fashion. The definition of feminine style was rapidly expanding: day dresses became shorter with lower necklines. At the same time, some wom en experimented with androgyny with suits and shorter hair à la Coco Chanel. This era was a shining beacon of hope for those living in its heart of New York City, signifying cultural change in favor of minority groups. Bubbling beneath its surface was an important literary movement that was dedicated to por traying the struggles of Black individ uals with integrity and nuance; these works were unafraid to ask difficult questions surrounding identity, auton omy, and injustice. Despite the Harlem Renaissance being most remembered for its jazziness and brevity, much of the art of this era is reflective and com

plex, investigating problems that peo ple today are still looking to answer.

An influential text that exemplifies this is Nella Larsen’s novel Passing, a realistic depiction of life for middle class Black women within the Harlem Renais sance. It was written in the latter part of the Harlem Renaissance in 1929, right before the damaging effects of the Great Depression. This book was adapted by Netflix into a film in 2021, receiving critical acclaim because of its costum ing, acting, and greyscale cinematog raphy that all thematically illustrate the struggle of existing ephemerally in a binary world. The story follows two light er-skinned Black women: Irene (Tessa Thompson) and Clare (Ruth Negga). Though Irene can “pass” as white in some social situations, she is married to a Black man, has a Black family, and navigates life as a Black woman. Clare has a similar complexion, but instead opts to marry a racist white man with no awareness of her Blackness and “passes” as white in all social contexts. The two women were friends from child hood; after they reunite by chance, Clare slowly begins to use Irene and her racial identity to reintegrate herself into Black circles. Their friendship puts both of their lives and identities in jeopardy, and

represents how the constructs of what we perceive as race are non-concrete and based entirely on social factors.

Passing explores Irene and Clare try ing to define themselves and gain con trol of their identities, in spite of a world that desperately wants them to adhere to strict racial and social categories. In the story, Irene tries to follow what so ciety has designated for her by leading a life in the most successful way she knows, creating a Black nuclear family and committing to living in the United States despite it being a hub for racebased hatred. Even though well-inten tioned, her living in this way inadvertent ly reinforces the same expectations that Clare is challenging. Irene’s conformity reflects the long-standing narratives surrounding respectability politics: an unspoken set of moral guidelines that people comply with in order to receive respect from society. Today, it is why children of BIPOC are sometimes given culturally “white” names to be more like ly to get job interviews and why Black women feel pressure to straighten their hair instead of wearing it naturally or wearing a weave - to falsify an adjacen cy to whiteness. These rules implicitly place whiteness as the innately most es teemed. This is why a white woman with

a “messy bun” is treated more seriously than a Black woman in a bonnet, even though neither style has more profes sional or aesthetic value than another.

Similar to notions of race, what is considered to be “respectable” is entire ly culturally constructed. At the crux of this phenomenon is a desire for better treatment from the majority white group, requiring BIPOC individuals to sacrifice traditional and cultural means in order to assimilate and appear more “pre sentable” and thus get treated better. This limits self-discovery and self-ex pression, restricting the purpose of in dividual aesthetics to be only for capi talistic gain and wider social approval, instead of treating appearance and presentation as the art form that it is.

By “passing” as a white woman, Clare goes against the grain and re jects society’s expectation for her. She gains access to privilege and oppor tunity by virtue of her appearing to be the oppressor. While momentarily this feels liberating, she still finds herself unfulfilled, thus explaining why she seeks out a friendship with Irene. Re gardless of how either woman presents, they are both punished and made un happy by the hands of the same sys tem. No matter how they behave, their behavior fortifies the same oppres sive system, like a game designed for no one to win. Though set during the Harlem Renaissance, BIPOC individ uals face similar struggles to this day.

Though seemingly ingrained within our culture, these issues do not have to be permanent.

To combat them, it is our responsibil ity to platform marginalized voices and

de-center acceptance from the majori ty as the inherent objective of equality. There is so much beauty and love to be found outside of the boundaries of white patriarchal society! Artists of the Harlem Renaissance shared this belief, and used it to gain creative traction in their time. Their work initially circulated in Black spaces; as it gained popularity within, it spread outward, including with in the white, general public. Creating a positive model against respectability politics by treating all forms of self-ex pression and styles with validity and positivity is something we can begin to carry out ourselves. In practice, this looks like investigating our own biases on what is or is not respectable. This can be as simple as asking yourself: “Why do I feel this way?” or “Who taught me to feel this way?” after making a judgment, and then challenging these same biases as they appear in others. What was first articulated in the Harlem Renaissance continues to be discussed in art today. Passing resonates with audiences nearly a hundred years lat er because of how it portrays the unre solved problem of respectability politics in a painstakingly cruel, yet truthful way. An emphatic rejection of respectability politics and its adjacently limiting ideals is how we can ensure that our individ ual ability to freely express ourselves and use aesthetics to convey meaning are protected, respected, and valued.

"

No matter how they be have, their behavior for tifies the same oppres sive system, like a game designed for no one to win. Though set during the Harlem Renaissance, BIPOC individuals face similar struggles to this day."

Corsets have long been a source of controversy. There’s a common theme in media that works to portray them as ‘patriarchal instruments of torture’ that strangle and suffocate women. While there’s a partial truth to this, there’s also much to be said about their practical functionality in day-to-day life. Just as today we have a wide variety of bras to suit every occasion, whether it be sport bras for athletics or bralettes for an aes thetic purpose, corsets were similarly diverse and encompassed all forms of activities. They didn’t solely belong to ballrooms and the absurdly wealthy aristocrats that could afford them – even working class women would slip into a corset each morning before tending to their household chores or labor-inten sive jobs.

Corsets were a staple of 19th and early 20th century fashion, and their purpose was threefold: first, they were used to modify the natural shape of a body; secondly, they helped ease the burdensome weight of garments off of the wearer; and third, they served as back and bust support during a time when bras had yet to be invented. When listed out like this, it’s easy to understand why corsets have been the

cause of dispute among historians. On their own, corsets were a harmless ar ticle of clothing and proved themselves helpful to the women of the time in pro viding structural support – but if pulled tightly across a woman’s body, they held the power to manipulate the very structure of her bones and weaken her overall health. This particular style of corsetry is called “tightlacing”, and it’s the true controversy of the corset. Often compared to Chinese foot-binding, it is the practice of using a corset to cinch the waist to achieve the coveted hour glass silhouette.

Though historians once be lieved the majority of middle and upper class women in England and America to have practiced tightlacing on a dai ly basis, as of recently, the consensus has changed. Now, it is held that only a small portion of aristocratic women even participated in body shaping– the rest, they believe, refrained from lac ing their corsets completely to keep it loose. Unlike the present day where corsets have evolved into tank tops that accentuate one’s thinness, it wasn’t so much the size of one’s body that mat tered, but whether the gown itself fit the fashionable standards.

Corsets of this decade emphasize the natural curve of the waist without any shaping. The waistline of this era is just below the bust, so the waist and hips aren’t visible in a gown.

The waistline drops down to the natu- ral waist, but hips still aren’t visible at this time. Stitched eyelets are used to lace the corset, and as they are particularly weak, they wouldn’t have been able to support tightlacing. Additionally, with tuberculosis running rampant at the time, any compression of the lungs was seen as a major health concern.

Gowns of this era are designed to accentuate a narrow waist. Corsets are made with metal grommets to make it easier to lace, especially for tightlacing (though tuberculosis was still a concern at this time). By using large skirts, women are able to create the illusion of a small waist.

There’s an expectation at this time that women will not have a flat stomach (due to an emphasis on fertility and pregnancy as a societal virtue), so the front of the corset bows out and curves around the front. Fashion at this time even accentuates the stomach.

S-bend corsets come into style. These corsets use a lot of padding under and over to achieve a full bust and full back so you end up with an “S” shape. May have caused the wearer discomfort due to its extreme shape, but it isn’t harmful.

With the men off fighting in WWl, women are expected to take on their jobs and responsibilities. Looser clothing comes into fashion, and corsets are traded in for girdles.

A boyish, box-shaped silhouette becomes all the rage. Gowns are loose and unsuggestive. Women use corset-like clothing to compress their chests (being flatchested was fashionable!)

Corsets return in style as lingerie and shapewear. Bra cups are built into the corset, and they are sometimes combined with a girdle for body shaping. This trend is short-lived due to its highly fetishized nature.

Corsets and girdles are abandoned. Instead, women focus on exercise and diet to achieve their ideal figure.

Vivienne Westwood incorporates corsets into her “punk” aesthetic. She transforms corsets from underwear to something to be seen externally by layering over clothing. Since then, corsets have been experimented with as a mode of fashion rather than something to shape or structure the body. Which, lastly, takes us to...

Corsets are reintroduced to the fashion world as tank tops. Rather than shape the body, they’re meant to lie atop it like a second skin and accentuate the pre-existing thinness of the wearer.

This timeline hardly encompasses the entirety of corsetry evolution, but it’is enough to give you the big picture: that Victorian corsets have been misrepresented and misjudged.

Aside from the practice of tightlacing, corsets weren’t created to constrict and disempower wom en. They were actually pretty important in providing the structural support necessary to labor through an intensive workday. In fact, it would be more fair to claim that the current use of corsets is the true prob lem. Unlike the Victorian era where the focus lies more on the gown than a woman’s figure beneath it, in present day society, the glorification of ‘nat ural beauty’ expects the corset-wearer to already be thin as to accentuate a naturally acquired tiny waist. Corsets now have less to do with functionality, and instead play an aesthetic role in one’s outfit. To some degree, corsets might always remain a matter of controversy. As long as society dictates what a woman’s body should look like, there will be pressure to adhere to it or risk alienation. This is especially made difficult with the fashion industry swift to supply the newest fad that “erases inches instantly” (cough cough, Kim Kardashian’s line of waist trainers). So let us once and for all cleanse the reputation of the corset and the women who wore them by remembering its true purpose: not to “improve” a woman’s figure, but her livelihood.