FORGING LEGACY

LEGENDS PAST & PRESENT A lso in this i ssue : P e P DePloyment An D s AR Postu Res o n l eADeRshi P, l egen Ds , An D l egAcies Rethink mine counte RmeAsu Res B uil D exPeDition ARy As W A iR - c omBAt elements Re- i mAgining the osPRey

2023 Number 160

-

SPRING

Naval Aviation has never been more relevant, or in demand, than it is today, and the Rotary Wing / Tilt Rotor communities play a vital role across the spectrum of warfare - providing lethality, maneuverability, and networked warfighting capabilities. The National Defense Strategy states that "the surest way to prevent war is to be prepared to win one." Therefore, Naval Aviation's priorities of Warfighting, People, and the Readiness of both, together with an increased and stable military budget through FY24, has positioned us well to maximize readiness and "be prepared to win."

This year's NHA Symposium theme, "Forging Legacy - Legends Past and Present,” celebrates the tremendous contributions of helicopter aviators, maintainers and support personnel to our nation and our Navy. The Rotary Force stands on the shoulders of these individuals who preceded us without a doubt. The focus of this Symposium is about storytelling and the sharing of unique experiences of NHA members (Vietnam era to present) who have had an impact upon culture and tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs). We learn from the past and use experience to master our warfighting craft. It is clear that forces operating both manned and unmanned rotary wing / tilt rotor aircraft, embarked in Carrier Strike Groups (CSGs) and Expeditionary Strike Groups (ESGs), as well as those performing expeditionary operations around the world, will be front and center in all future conflicts.

The health of the Rotary Force is encouraging and impressive, providing Fleet commanders with an on-call capability to protect U.S. and allied capital ships, sink enemy ships and submarines, and find, identify, and engage undersea targets and mines. Our squadrons support SOF forces from bases around the world and train with vital coalition and joint partners to hone their skills and improve our interoperability and joint warfighting effectiveness. If that were not enough, the logistical support helicopters and tilt rotors provide, including SAR and CSAR, is critical to our ships and strike groups' current and future successes. The contributions that Navy rotary wing aviation provides our nation cannot be overstated. We cannot operate as a modern Navy without the vitality, lethality, and diversity of the Rotary Force.

The Department of Defense operates as a Total Force, and the Naval Aviation rotary wing is no different with Reserves at HSM-60, HSC-85, SAUs, and TSUs augmenting as vital force multipliers. Executing missions that take an incredible level of skill and experience, our reserve component capability is unquestioned and continually adds to the undeniable legacy of rotary wing aviation. Also part of that Total Force are our civilian Sailors. Navy civilians who support our community at various activities and in numerous roles. To them, we owe a debt of gratitude and like us, they also stand on the shoulders of giants who preceded them.

Today's rotary wing and unmanned rotary platforms enjoy leading-edge technologies, but it is our high level of training that provides the asymmetric advantage in combat. Regardless of how capable our equipment and the equipment of our adversaries, experience teaches us that highly trained warfighters win in combat. As Naval Aviators, we also understand that in combat, we do not rise to the level of our expectations. Rather, we fall to the level of our training. Therefore, we owe it to our Aircrew and Sailors that they receive the best and most realistic training possible.

I encourage you to engage with our industry partners at Symposium. Challenge them to improve the equipment we currently have and to incorporate technology into future designs that enhance mission success. New technology should be operationally effective, provide improved lethality, be totally interoperable with existing CSG and ESG systems, and easy to use and maintain. Our Naval Aviation Enterprise relies on the ingenuity of Fleet operators and the creativity of the private sector to transition great ideas into warfighting reality

Enjoy Symposium and bring your hard questions to the Flag Panel!

We Fly, We Fight, We Lead, We Win!

Kenneth Whitesell

Vice Admiral, U.S. Navy

Symposium - from

Welcome to

the Air Boss

Spring 2023

ISSUE 160

About the cover: The Warlords of HSM51 and Golden Falcons of HSC-12, both stationed at NAF Atsugi, Japan as part of the Forward Deployed Naval Force (FDNF) conducting a formation flight for a USNA Spirit Spot for the 2022 ARMY NAVY Football Game. Photo by: MC2

Ange Olivier Clement

Ange Olivier Clement

Rotor Review (ISSN: 1085-9683) is published quarterly by the Naval Helicopter Association, Inc. (NHA), a California nonprofit 501(c)(6) corporation. NHA is located in Building 654, Rogers Road, NASNI, San Diego, CA 92135. Views expressed in Rotor Review are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the policies of NHA or United States Navy, Marine Corps, or Coast Guard. Rotor Review is printed in the USA. Periodical rate postage is paid at San Diego, CA. Subscription to Rotor Review is included in the NHA or corporate membership fee. A current corporation annual report, prepared in accordance with Section 8321 of the California Corporation Code, is available on the NHA Website at www. navalhelicopterassn.org.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Naval Helicopter Association, P.O. Box 180578, Coronado, CA 92178-0578.

Rotor Review supports the goals of the association, provides a forum for discussion and exchange of information on topics of interest to the Rotary Force and keeps membership informed of NHA activities. As necessary, the President of NHA will provide guidance to the Rotor Review Editorial Board to ensure Rotor Review content continues to support this statement of policy as the Naval Helicopter Association adjusts to the expanding and evolving Rotary Wing and Tilt Rotor Communities .

FOCUS: Forging Legacy - Legends Past & Present

The Legacy of the Navy’s Helo Master Plan, Circa Early 2000’s.........................................24

By VADM Dean Peters, USN

Radio Check - Legends...................................................................................................................26

The 1986 Gander Medevac.........................................................................................................30

By RADM Steve Tomaszeski, USN (Ret.) and CDR Roy Resavage, USN (Ret.)

Sikorsky, A Lockheed Martin Company, Celebrates 100 Years of Innovation..................34 Forging a Legacy of Naval Helicopter Capability

By Shawn Malone, Strategy and Business Development Principal Analyst for Sikorsky, A Lockheed Martin Company

A Long Way, and Not So Long Ago.............................................................................................44

By CAPT Joellen Drag Oslund, USN (Ret.)

Fly to Fight, Fight to Win ..............................................................................................................46

By LCDR Robert E. Swain III, USN

CAPT Joellen Drag Oslund: Paving the Way for Female Aviators.........................................52

By LT Elisha Clark, USN

FEATURES

Build Expeditionary ASW Air - Combat Elements.....................................................................56

By CDR Matt Wright, USN and CDR Jamie Powers, USN

Re-imagining the Osprey: The Impact of the CMV-22B Osprey on the United States Navy............................................................................................................60

By Robbin Laird

Rethink Mine Countermeasures - A Get Real Get Better Approach................................62

By CDR Nick “TRON” Schnettler, USN and LT Charlie “Handy Man” Thomas, USN

PEP Part 5 - PEP Deployment & SAR Postures.......................................................................64

By LCDR Randy Perkins, USN

Read Rotor Review on your Mobile Device

Did you know that you can take your copy of Rotor Review anywhere you want to go? Read it on your kindle, nook, tablet or on your phone. Rotor Review is right there when you want it. Go to your App Store. Search for Naval Helicopter Events. On the home screen, hit the Rotor Review button. It will take you to Issuu, our digital platform host. There you can read the current magazine. Scroll down to "Read Articles. This option is formatted for your phone. or you can view or download or print the two page spread.You also have access to all previous issues by searching on Google for Rotor Review or browsing through Issuu's website.

Rotor Review #160 Spring '23 2

COLUMNS

Executive Director's View.........................................................................................................8

Vice President of Membership Report.................................................................................10

From the Editor-in-Chief........................................................................................................12

On Leadership .........................................................................................................................14

On Legacies and Legends By VADM Jeffrey W. Hughes, USN

Commodore's Corner............................................................................................................16

We Have the Potential to Be Legendary By CAPT Chris “Jean-Luc” Richard, USN

NHA J.O. President Update....................................................................................................17

Scholarship Fund Update ......................................................................................................18

Historical Society.....................................................................................................................20

View from the Labs ...............................................................................................................22

By CAPT George Galdorisi, USN (Ret.)

DEPARTMENTS

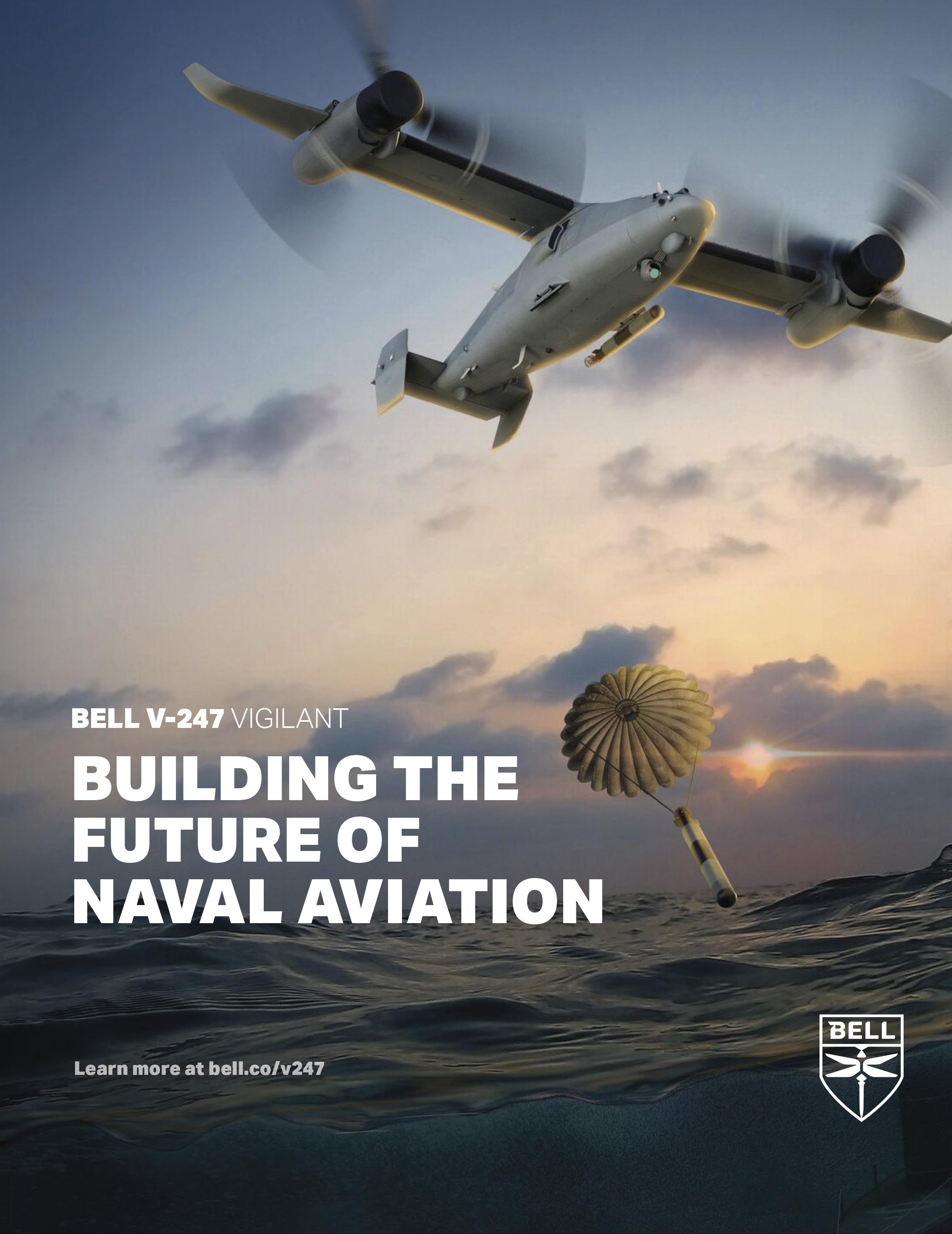

Industry and Technology........................................................................................................68

Time for the Navy To Set a Clear Course for Rotorcraft Modernization

By Carl Forsling and Chris Misner; Senior Managers at Bell

Change of Command..............................................................................................................70

Squadron Updates...................................................................................................................72

Mules and War Bears By LCDR Brian "Frommers" Strong, USN

Off Duty.....................................................................................................................................74

Book Review: Helicopter Heroine by Charles Morgan Evans

Movie Review: Devotion

Reviewed by LCDR Chip Lancaster, USN (Ret.)

Engaging Rotors.......................................................................................................................78

Signal Charlie............................................................................................................................82

Editorial Staff

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

LT Annie "Frizzle" Cutchen, USN annie.cutchen@gmail.com

MANAGING EDITOR

Allyson "Clown" Darroch rotorreview@navalhelicopterassn.org

COPY EDITORS

CDR John Ball, USN (Ret.) helopapa71@gmail.com

CAPT John Driver, USN (Ret.) jjdriver51@gmail.com

LT Elisha "Grudge" Clark, USN elishasuziclark@gmail.com

AIRCREW EDITOR

AWR1 Ronald "Scrappy" Pierpoint, USN pierpoint.ronald@gmail.com

COMMUNITY EDITORS

HM

LT Molly "Deuce" Burns, USN mkburns16@gmail.com

HSC

LT John “GID’R” Dunne, USN john.dunne05@gmail.com

LT Tyler "Benji" Benner, USN tbenner92@gmail.com

LT Andrew "Gonzo" Gregory, USN andrew.l.gregory92@gmail.com

LT Fred "Prius" Shaak, USN fshaak@gmail.com

HSM

LT Joshua "Hotdog" Holsey, USN josholc@gmail.com

LT Abby "Abuela" Bohlin akguerra023@gmail.com

LT Thomas "Buffer" Marryott Jr, USN tmarryott@gmail.com

LT Nathan "MAM" Beatty, USN nathan.g.beatty@gmail.com

LT Jared "Dogbeers" Jackson, USN jared.d.jack@gmail.com

USMC EDITOR

Previous Rotor Review Editors

Wayne Jensen - John Ball - John Driver - Sean Laughlin - Andy Quiett

Mike Curtis - Susan Fink Bill Chase - Tracey Keefe - Maureen Palmerino

Bryan Buljat - Gabe Soltero - Todd Vorenkamp - Steve Bury - Clay Shane

Kristin Ohleger - Scott Lippincott - Allison Fletcher Ash Preston - Emily LappMallory Decker - Caleb Levee - Shane Brenner - Shelby Gillis - Michael Short

©2023 Naval Helicopter Association, Inc., all rights reserved

Maj. Nolan "Lean Bean" Vihlen, USMC nolan.vihlen@gmail.com

USCG EDITOR

LT Marco Tinari, USCG marco.m.tinari@uscg.mil

TECHNICAL ADVISOR

LCDR Chip Lancaster, USN (Ret.) chipplug@hotmail.com

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 3

Chairman’s Brief .......................................................................................................................6 National President's Message.................................................................................................7

Thank You to Our Corporate Members - Your Support Keeps Our Rotors Turning

To get the latest information from our Corporate Members, just click on their logos.

Rotor Review #160 Spring '23 4

Gold SupporterS executive SupporterS

Small

BuSineSS partnerS platinum SupporterS

Naval Helicopter Association, Inc.

P.O. Box 180578, Coronado, CA 92178-0578 - (619) 435-7139

www.navalhelicopterassn.org

National Officers

President....................................CDR Emily Stellpflug, USN

Vice President ........................................CDR Eli Owre, USN

Executive Director...............CAPT Jim Gillcrist, USN (Ret.)

Business Development..............................Ms. Linda Vydra

Managing Editor, Rotor Review .......Ms. Allyson Darroch

Retired Affairs ..................CDR Mike Brattland, USN (Ret.)

Legal Advisor...............CDR George Hurley, Jr., USN (Ret.)

VP Corp. Membership..........CAPT Tres Dehay, USN (Ret.)

VP Awards.................................CDR Philip Pretzinger, USN

VP Membership ...............................LCDR James Teal, USN

VP Symposium 2023 .............................CDR Eli Owre, USN

Secretary..........................................LT Jimmy Gavidia, USN

Special Projects........................................................VACANT

NHA Branding and Gear...............LT Shaun Florance USN

Senior HSM Advisor.............AWRCM Nathan Hickey, USN

Senior HSC Advisor..................AWSCM Shane Gibbs, USN

Senior VRM Advisor........AWFCM Jose Colon-Torres, USN

Directors at Large

Chairman...............................RADM Dan Fillion, USN (Ret.)*

CAPT Gene Ager, USN (Ret.)*

CAPT Chuck Deitchman, USN (Ret.)*

CAPT Dennis DuBard, USN (Ret.)*

CAPT Tony Dzielski, USN (Ret.)*

CAPT Greg Hoffman, USN (Ret.)*

CAPT Bill Personius, USN (Ret.)*

CAPT Mario Mifsud, USN (Ret)*

CAPT Arne Nelson, USN (Ret.)*

CAPT Matt Schnappauf, USN (Ret.)*

LT Alden Marton, USN*

AWRCM Nathan Hickey, USN*

*Also serving as Scholarship Fund Board Members

Junior Officers Council

Nat’l Pres............................ LT Alden "CaSPR" Marton, USN

Region 1........................LT Ryan "Shaggy" Rodriguez, USN

Region 2 ......................................LT Rob "JORTS" Platt, USN

Region 3 ..............LT Harrison "Dusty Bottoms" Pyle, USN

Region 4 ................................LT Rochelle "PG" Balum, USN

Region 5................................LT Chris "BOTOX" Stuller, USN

Region 6....................................LT Robert "DB" Macko, USN

NHA Scholarship Fund

President .............................CAPT Arne Nelson, USN (Ret.)

Executive VP/ VP Ops ...CAPT Todd Vandegrift, USN (Ret.)

VP Plans................................................CAPT Jon Kline, USN

VP Scholarships ..............................Ms. Nancy Ruttenberg

VP Finance ...................................CDR Greg Knutson, USN

Treasurer........................................................Ms. Jen Swasey

Webmaster........................CDR Mike Brattland, USN (Ret.)

Social Media .............................................................VACANT

CFC/Special Projects ...............................................VACANT

CDR

CDR

Regional Officers

Region 1 - San Diego

Directors ......................................CAPT Chris Richard, USN

CAPT Ed Weiler, USN

CAPT Justin McCaffree, USN

CAPT Nathan Rodenbarger, USN

President ............................ CDR Dave Vogelgesang, USN

Region 2 - Washington D.C.

Director ........................................ CAPT Andy Berner, USN

President ...........................................CDR Tony Perez, USN

Co-President.................................CDR Pat Jeck, USN (Ret.)

Region 3 - Jacksonville

Director...................................CAPT Teague Laguens, USN

President........................................CDR Dave Bizzarri, USN

Region 4 - Norfolk

Director...................,........................CAPT Ed Johnson, USN President ............................ CDR Santico Valenzuela, USN

Region 5 - Pensacola

Director ...........................................CAPT Jade Lepke, USN President .........................................CDR Annie Otten, USN '23 Fleet Fly-In Coordinator...............LT Chris Stuller, USN

Region 6 - OCONUS

Director ...........................................CAPT Mike O'Neil, USN President ....................CDR M. E. Kawika Chang, USN

NHA Historical Society (NHAHS)

President............................CAPT Bill Personius, USN (Ret.)

VP/Webmaster..................CDR Mike Brattland, USN (Ret.)

Secretary................................LCDR Brian Miller, USN (Ret.)

Treasurer...........................CDR Chris Fitzgerald, USN (Ret.)

S.D. Air & Space Museum.....CAPT Jim Gillcrist, USN (Ret.)

NHAHS Committee Members

CAPT Dennis DuBard, USN (Ret.)

CAPT Mike Reber, USN (Ret.)

CAPT Arne Nelson, USN (Ret.)

CAPT Jim O’Brien, USN (Ret.)

CAPT Curtis Shaub, USN (Ret.)

CAPT Mike O’Connor, USN (Ret.)

CDR John Ball, USN (Ret.)

CDR Chris Fitzgerald, USN (Ret.)

CDR Chip Lancaster, USN (Ret.)

Master Chief Dave Crossan, USN (Ret.)

CAPT

CAPT

CDR

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 5

CDR D.J. Hayes, USN (Ret.)

C.B. Smiley, USN (Ret.)

J.M. Purtell, USN (Ret.)

H.V. Pepper, USN (Ret.)

CAPT A.E. Monahan, USN (Ret.)

CAPT Mark R. Starr, USN (Ret.)

CAPT A.F. Emig, USN (Ret.) Mr. H. Nachlin

CDR H.F. McLinden, USN (Ret.)

W. Straight, USN (Ret.)

P.W. Nicholas, USN (Ret.)

Navy Helicopter Association Founders

NHA Symposium 2023

By RADM D.H. “Dano” Fillion, USN (Ret.)

By RADM D.H. “Dano” Fillion, USN (Ret.)

his book, "The SOUL of a Team," NFL Hall of Fame, Super Bowl winning Coach Tony Dungey is asked to help a friend figure out why the fictional Orlando Vipers are not performing to the level that everyone believes the team should be reaching. Excerpt from The SOUL of a Team: “After meeting with the coaching staff and observing the team throughout the off-season, Tony quickly realizes the problem: The Vipers lack ‘SOUL.’”

InRelax, I am not going to deliver a sermon here, but I could! Coach Dungey defines the acronym “SOUL” as Selflessness, Ownership, Unity, and Larger Purpose.

The theme of this year’s National Symposium is “Forging Legacy - Legends Past and Present.” The women and men we as the membership of NHA will hear from by sharing their respective stories will epitomize the tenants that Coach Dungey describes in his book as the absolute pillars required to build a successful team! We, the current membership of NHA both active and retired, have all in some way benefited from the accomplishments of our past legends and are seeing first hand how the rotary wing current leaders are Forging a Legacy for the entire Rotary wing component of the Naval Aviation Enterprise (NAE). The membership, comprised of our pilots, AWR/S/F’s, our amazing maintainers / support teams / industry partners, and retired Legends (all in our own minds) have in some way over the years contributed to building a team with SOUL!!!

"Forging Legacy - Legends Past and Present” is a theme for Symposium that we have never explored with this much granularity and focus. It promises to be interesting, entertaining and inspiring for sure. See you there and if you can't be with us at Harrah's, then watch our Facebook Live page so you won’t miss any of our Legends Past and Present; bring your SOUL!!!

As always, I am, V/r and CNJI (Committed Not Just Involved), Dano

Rotor Review #160 Spring '23 6 Chairman’s Brief

“Any nation that does not honor its heroes will not long endure.”

President Abraham Lincoln

Forging Legacy

By CDR Emily “ABE” Stellpflug, USN

Irecently had the privilege of hosting CAPT Joellen Drag Oslund, USNR (Ret.) and her husband, CAPT Dwayne Oslund, USN (Ret.), at VRM-50 for our Women’s History Month Celebration. CAPT Oslund was one of the first six women enrolled in Naval flight training as part of an “experiment” in 1973 and the FIRST woman helicopter pilot! Her bravery and fortitude proved that women are capable of being aviators and challenged law that prevented women from landing on or serving aboard Naval vessels.

In 1978, her efforts opened the door to shipboard duty for women. Her husband provided critical support and allyship along a difficult path as she was doubted by many along the way. Their story is remarkable and has had long-lasting impacts to where we are today as a rotary force and greater Naval Aviation Enterprise. We are thrilled to have CAPT Oslund attending this year’s NHA Symposium as the speaker at Friday’s breakfast— Celebrating 50 Years of Women Flying in Naval Aviation.

This year marks many important milestones, 100 Year Sikorsky Aircraft Co. Anniversary, 80 Years of Sikorsky Helicopters, and 50 years of Women Flying in Naval Aviation, all of which were part of the inspiration for the theme for our NHA Symposium: "Forging Legacy—Legends Past and Present." The NHA Symposium will be packed with legends from Vietnam era and beyond as well as present leaders who are forging the path for the future of Naval Aviation.

The following are some key events:

• Annual Golf Tournament

• Members’ Reunion

• Flight Suit Social

• “The Challenge” – a physical fitness team competition

• Keynote Speaker – CDR “Willy” Driscoll, USN (Ret.), a Vietnam Ace

• Past Legends Panel – featuring rotary legends of our past

• Forging Legacy Panel – featuring rotary leaders of today and the future

• Breakfast Celebrating 50 Years of Women Flying in Naval Aviation

• JO Call with Air Boss

• Captains of Industry Panel

• Commodore / CAG Panel

• Flag Panel

Please make your room reservations and register now! We look forward to seeing you at Harrah’s for a phenomenal Symposium!

Fly Safe!

V/R ABE, NHA Lifetime Member #481

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 7

National President's Message

2023 NHA National Symposium “Forging Legacy - Legends Past and Present”

By CAPT Jim Gillcrist, USN (Ret.)

Itseems appropriate that the JOs and Aircrew have anchored in on this as the theme for the 2023 NHA National Symposium. We have all benefited from the legends who preceded us and are better for it. To say that we “stand on their shoulders” is a wonderful acknowledgement. This Symposium is a chance to reconnect with community legends, recognize them for leading the way, and say thank you.

Every day, I am privileged to interact with active duty and retired members of the Rotary Wing / Tilt Rotor Community – pilots, aircrewmen, and maintainers, all of whom are past and present legends among us. The legends I am talking about are all those folks who took each of us to sea: Detachment LPOs, Det CPOs, Det HACs, and Det OICs who guided, shaped, mentored, and forged who we are as leaders and aviators.

In fact, there are several legends from my first two detachments who proved foundational in my Navy career – these individuals shaped me as a Naval Officer and Aviator. Their mentorship and example enabled me to excel first as a Detachment Admin / Operations / Aircrew DIVO and then as a DETMO. I owe a debt of gratitude to these following legends:

• HSL-37 Det1C OIC, LCDR Dick Sears, & Det Chief, AECS Shotwell

• HSL-37 Det 4 OIC, LCDR Jack Coyne, & Det Chief, ADC Lanny Cornell

And you might say that NHA is forging its own legacy by single siting the Annual Symposium at Harrah’s Resort for 2023, 2024, and 2025. We have a lot in store for you so REGISTER and MAKE YOUR ROOM RESERVATIONS. Milestones we will be celebrating include:

• 50 Years of Women Flying in Naval Aviation

• 55 Year Anniversary of the Clyde Lassen Medal of Honor Rescue

• 80 Years of Sikorsky Helicopters

• 100 Years of Sikorsky Aircraft

Additionally, NHA is returning to a printed Rotor Review Magazine for those who want it. The catch is that every member needs to update their magazine preference, mailing address, and region. Otherwise, you will continue to default to an electronic copy. I hope you enjoy reading some truly great columns in the Pre-Symposium Issue of Rotor Review that include:

• “On Leadership Column” by VADM Jeff Hughes, USN

• “The Legacy of the Navy’s Helo Master Plan” by VADM Dean Peters, USN (Ret.)

• “The 1986 Gander MEDEVAC” by RADM Steve Tomaszeski, USN (Ret.)

• “Commodore’s Corner” by CAPT Chris Richard, USN

• “Sikorsky Celebrates 100 Years of Innovation” by CAPT Shawn Malone, USN (Ret.)

IN CLOSING, WE ARE A RELATIONSHIP ORGANIZATION. Meaning that the relationships we make at the squadron and aboard ship on deployment are lifelong, enriching, and purposeful. These same relationships continue downstream and remain powerful in our military careers, as well as when we transition to our next adventure outside of the service. We look after one another and pay it forward continuously. This is why we are members of our professional organization. And this is why we gather once a year at Symposium.

So, please keep your membership profile up to date. If you should need any assistance at all, give us a call at (619) 435-7139 and we will be happy to help – you will get Linda, Mike, Allyson, or myself.

Warm regards with high hopes, Jim Gillcrist.

Rotor Review #160 Spring '23 8 Executive Director’s View

Every Member Counts / Stronger Together

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 9

LT Madalyn Thompson, USN / HSM-41 LTM #712

CAPT Bob Doane, USN (Ret.) LTM #696

LCDR Brittany Nelms, USN / HSM-75 LTM #235

LT Elias Ney, USN / HSM-49 LTM #710

LT Zoe MacFarlane, USN / HSC-3 LTM #693

LT Gabby Feldman, USN / HSM-49 LTM #646

Congratulations and Thank You to our Newest Lifetime Members!

Whiting Field: The Past and the Present

By LCDR Bill "WYLD Bill" Teal, USN

I’mblessed to work with the future of Naval Aviation everyday at South Whiting Field. And with the arrival of the TH-73 Thrasher, I get a front row seat to forging a new legacy of Helicopter Aviation. But even with all of that, I’m very excited for this issue to learn about all the legends who have impacted our community over the years. I’m also excited to learn about some of the living legends among us shaping the future.

When I think of someone who is a legend in a sport or field, it is not just for his or her talents. A true legend is someone who leaves an impact past his or her time on the field or in the cockpit. They make a change to the sport or community that is undeniable. A true legend reinvents the sport or creates such a cultural shift that the “old-way” just can’t compete anymore.

I know each and every one of you reading this is the "best pilot" the Navy has seen since Chuck Yeager. But, if it’s been a hot minute since you’ve wiggled the sticks, or your AFCS OFF approach can be confused for FAM 2 at Spencer Field, fear not, you too can be a legend. You can leave a lasting legacy on the community by strengthening its reach. Encourage your wardroom to join, talk to your former Naval Helicopter Aviator co-workers - encourage them to join. Tell those Osprey pilots that they landed vertically and they should join too, I mean after all, everyone was once that FAM 2 at Spencer.

Your Legacy is to continue to spread the fellowship that can be found in NHA. We are 3,000 members strong and growing. Captain Gillcrist signs off every column, “We are stronger together and every member counts.” And he hit the nail on the head. Help build our legacy by reaching out to those old squadron mates and encouraging them to join. And seriously, if your approaches can be confused with a FAM 2, reach out to me and let’s see what we can do for you!

Rotor Review #160 Spring '23 10 VP of membership Report

Forging Legacy - Legends Past & Present

By LT Annie "Frizzle" Cutchen, USN

The Naval Helicopter Association team developed what has already been proven to be a wonderful theme for symposium 2023. “Forging Legacy—Legends Past and Present” has resulted in so many truly inspiring submissions for this issue of Rotor Review. Even ten years ago, I don’t know that we would have the buy-in from leaders outside of the community that we do today.

So, how did we get here? We got here because of the legends that paved the way for us and continue to grow our sphere of influence and legacy through the involvement of the readership. This year marks many milestones for Naval Aviation, including the 100-year anniversary of Sikorsky Aircraft Co., 80 years of Sikorsky Helicopters, and 50 Years of Women Flying in Naval Aviation.

Celebrating 50 years of women flying in Naval aviation feels particularly meaningful to me. When I joined the Navy in 2014 (not all that long ago), there were career women pilots still on active duty who had no choice in the aircraft they flew based on the combat restrictions imposed on them. This was shocking to me. Now I go to events like the NHA Symposium, look around the room, and there are people that look like me. They are not just in the crowd, but on the panels and in leadership positions. We have come so far and are still growing.

We were fortunate enough to have CAPT Joellen Drag Oslund author an article in this issue about the first few women helicopter pilots and some of the trials and tribulations they faced. How incredible to have one of the women who made history speak to this community on such a personal level. Additionally, CAPT Oslund was kind enough to take the time to be interviewed by LT Elisha “Grudge” Clark. Grudge wrote up the interview in a way that truly tells the story of CAPT Oslund’s personal journey. I look forward to highlighting more incredible legends in future issues this year to continue to celebrate this milestone.

I hope to see you all at Harrah’s for NHA Symposium this May and continue to learn and grow through our interactions and learn about the growing legacy that is Naval Rotary Wing Aviation.

V/r, LT Annie “Frizzle” Cutchen annie.cutchen@gmail.com annie.l.cutchen.mil@us.navy.mil

Rotor Review #160 Spring '23 12 From the Editor-in-Chief

Letters to the Editors

It is always great to hear from our membership! We need your input to ensure that Rotor Review keeps you informed, connected, and entertained. We maintain many open channels to contact the magazine staff for feedback, suggestions, praise, complaints or publishing corrections. Please advise us if you do not wish to have your input published in the magazine. Your anonymity will be respected. Post comments on the NHA Facebook Page or send an email to the Editor-in-Chief. Her email is annie.l.cutchen.mil@us.navy.mil, or to the Managing Editor at rotorreview@navalhelicopterassn.org. You can use snail mail too. Rotor Review’s mailing address is: Letters to the Editor, c/o Naval Helicopter Association, Inc., P.O. Box 180578, Coronado, CA 92178-0578.

RADIO CHECK

Tell Us What You Think!

The Rotor Review team will be keeping an ear to the ground at Symposium to develop a theme for our next issue (#161) that reflects what our NHA members are passionate about. Symposium brings many thought provoking and informative events, opportunity for mentorship, a chance to connect with friends and colleagues from the past, and quite a bit of fun.

What was the most impactful event at NHA Symposium and why? What new connections did you make?

With the theme “Forging Legacy–Legends Past and Present” in mind, what legacy has already been forged in Naval Aviation or your respective community? What is the legacy we are still forging? Are we on the right track or is there opportunity for a course correction?

We want to hear from you! Please send your responses to the Rotor Review Editor-in-Chief at the email address listed below.

V/r, LT Annie “Frizzle” Cutchen Editor-in-Chief, Rotor Review annie.cutchen@gmail.com

Articles and news items are welcomed from NHA’s general membership and corporate associates. Articles should be of general interest to the readership and geared toward current Navy, Marine Corps and Coast Guard affairs, technical advances in the rotary wing / tilt rotor industry or of historical interest. Humorous articles are encouraged.

Rotor Review and Website Submission Guidelines

1. Articles: MS Word documents for text. Do not embed your images within the document. Send as a separate attachment.

2. Photos and Vector Images: Should be as high a resolution as possible and sent as a separate file from the article. Please include a suggested caption that has the following information: date, names, ranks or titles, location and credit the photographer or source of your image.

3. Videos: Must be in a mp4, mov, wmv or avi format.

• With your submission, please include the title and caption of all media, photographer’s name, command and the length of the video.

• Verify the media does not display any classified information.

• Ensure all maneuvers comply with NATOPS procedures.

• All submissions shall be tasteful and in keeping with good order and discipline.

• All submissions should portray the Navy, Marine Corps and Coast Guard and individual units in a positive light.

All submissions can be sent via email to your community editor, the Editor-in-Chief (annie.l.cutchen.mil@us.navy.mil), or the Managing Editor (rotorreview@navalhelicopterassn.org). You can also use the USPS mail. Our mailing address is Naval Helicopter Association

Attn: Rotor Review

P.O. Box 180578

Coronado, CA 92178-0578

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 13

On Legacies and Legends

By VADM Jeffrey W. Hughes, USN

IthoughtI would begin with my take on the theme for Symposium this year. “Forging Legacy - Legends Past and Present,” it seems obvious and in looking at the definitions for legacy and legends I offer the following assessment. Legacy is something transmitted by or received from an ancestor or predecessor or from the past, where a legend is a person or thing that inspires. The confluence is how we are inspired by those with whom we serve, have served or have preceded us in charting the course for our development and that of the community. How this inspiration manifests itself among us is both broad and potentially unique to each of us individually, but I believe there are elements of this that determine who we are as a community. Things that collectively define us and make us proud. Things that are core to who we are and will transcend our time to those who follow us. Enough philosophy, what’s the so what. I see three themes for us to consider during this upcoming Symposium. First, recognition and celebration of those legends that have guided our individual and collective journeys. Second, a reflection on the evolution of the community to provide the ready forces necessary to conduct missions uniquely suited to naval rotary wing aviation. Third, given that there is an action word that precedes legacy – forging – this is our call to action to accelerate the preparation necessary for us to succeed in competition against comprehensive adversaries – now and in the future.

History is replete with stories of aviators, aircrewmen, and technicians who enabled the conduct of or flew daring missions that yielded consequential outcomes. But, I would contend that we should also recognize those legends that inspire us daily to be the very best versions of our professional selves. So who are these legends – maybe your on-wing instructor in HTs, the FRS instructor who flew night DLQs with you for the first time, your fellow H2Ps grinding it out with you during the initial stages of your first tour, the HAC with whom you were paired for extended periods on cruise, your Detachment Officer-in-Charge (Det OIC), your first Leading Chief Petty Officer, the junior crewman who made the difference during a varsity mission, the list could go on forever and never stops.

I recently assumed the prestigious honor of serving as the Golden Helix – the naval aviator on active duty with the earliest date of designation as a naval helicopter pilot. What made it more special than what appears at face value is that I replaced a legend – per the criteria above – in the former Vice Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Bill Lescher. Then LCDR Lescher was a Department Head/Det OIC in HSL44 in the early 1990s when I was a nugget. I learned much from him, both in the air and on deck, and this developmental

(and personal) relationship continued on for three decades where I most recently served for him as Vice Chief. It is also noteworthy that during this same timeframe, my second CO went on to serve as one of the community’s first Vice Admirals. Not too many rotary wing flag officers back in the 1990s - that tide has turned.

There are many ways to define what success looks like in reference to your personal legends, but take the opportunity periodically to reflect on those special people who made you great. Seek them out and tell them – the NHA Annual Symposium is always a great venue to do this. Also, never forget that YOU are a legend to many with whom you serve. Bear the standard and raise our collective game.

When I think of the legends of the community, and their tremendous legacy, I find a common theme over the nine decades of Naval Rotary Wing Flight – that being the adaptation and deliberate evolution to bring our warfighting capabilities to the fore in ever-changing and dynamic security environments. As I ponder the breadth of missions we have performed throughout our rich history, I assess that what they all have in common is the need for a machine/weapons system to possess certain flight attributes to accomplish a mission that few others could perform. From timely SAR, to open ocean spacecraft recovery, to riverine warfare, to overthe-horizon targeting and extended electronic warfare, to precision ASW weapon employment, to combat logistics – we bring results that have proven decisive for decades. While the actual mission outcomes are the stuff of legend, I will contend that the forethought and deliberate force development of the Rotary Wing Community warrants celebration. This doesn’t just happen. Legends in the past have brilliantly predicted warfighting capability gaps and opportunities and drove the evolution, and in some cases transformation, of our community to meet validated needs. As I look at the current and likely future security environment, I see another inflection point where the Naval Service will look to its

Rotor Review #160 Spring '23 14

On Leadership

Expeditionary Strike Group (ESG) 2

rotary wing community to bring capability to naval core missions like Sea Control/Denial, Power Projection, Maritime Security and Safety, and Sealift. Much like we did during the incredibly successful implementation of the Navy Helicopter Master Plan / CONOPS that delivered tangible mission outcomes via the evolved HSM/HSC/HM Communities, we find ourselves in position to define the needs for the coming decades. What made the last transition so successful is that we focused on much more than just the evolution of our platforms. We looked at the best ways to organize, train, and equip. We put mission focused community expertise in positions of great influence to drive outcomes. We charted the course for the development and employment of manned-unmanned teaming. Many legends of our community – to include names you probably have not heard – were responsible for the most comprehensive and successful transition in the history of Naval Aviation.

It’s now our turn – we have the controls to forge the legacy of the future of the community, where we will arguably face the greatest challenges across the spectrum of conflict in history. So here is the call to action – tell us where you see the community in the coming decades. How to use existing kit differently or employ more creatively today? What are the capabilities that we design, develop and deliver to meet the six CNO NAVPLAN defined force design imperatives – distance, deception, defense, distribution, delivery, and decision

advantage? How do we best experiment, learn, and adjust to enable our naval capstone concept – Distributed Maritime Operations – to yield the warfighting and deterrence outcomes we must deliver for the Joint and Combined Force. We rely on your thoughtful and well informed contribution and must incorporate it into the community design for future vertical lift (FVL).

My charge to us all – active, reserve, retired, industry – is to be legendary in what it is you do right now, but help us find that next gear as a learning and adaptive organization to appropriately posture for the future. The upcoming Symposium in the new venue is the opportunity for us to celebrate our legends and forge our legacy!

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 15

Squadronmates from a few different tours at the NHA 2022 Symposium.

We Have the Potential to Be Legendary

By CAPT Chris “Jean-Luc” Richard, USN, HSMWP

AsI thought about the theme of our upcoming Symposium, “Forging Legacy—Legends Past and Present,” I struggled a bit with what to write. Most of us have not been privileged to personally know any aviation heroes (from the historical perspective), but we know their stories. Our profession is rich in their exploits. They represent the best of us, and they exemplify the courage under fire that we all hope to exhibit if tested. At the most basic level, they show us what is possible when preparation and discipline collide, head first, with adversity. Nevertheless, heroes like Clyde Lassen, Stephen Pless, and Charles French are not part of our first-person experiences, and none of them need a neophyte like me retelling their stories (Google is your friend).

At an uncharacteristic loss for words, I did what I often do in cases like this: I went back to the definition. In reality, our lives are full of people who qualify as legends. In fact, we are all exactly one catastrophic event away from being legendary ourselves. Captain “Sully” Sullenberger did not wake up on January 15, 2009 planning to heroically ditch his Airbus A320 in the Hudson River. He and his copilot were confronted with an extraordinary challenge, and they instinctively relied upon the quality of their training. There was precious little time for debate; they processed the information that their jet was giving them, made a quick risk decision, and fell back upon their preparation to safely ditch their plane in the Hudson River. It was extraordinary airmanship to be sure, but I submit that decisiveness and exceptional Crew Resource Management (CRM) were key to the outcome.

Whether courage under fire or the disciplined procedural execution, many of us have had experiences in the aircraft in which—were it not for preparedness—the outcome could have been catastrophic. I personally know people who have autorotated to the water, landed single-engine on small ships, fought in-flight engine fires at night, egressed from a sinking aircraft, and dealt with total AC power failures in instrument conditions—just to name a few. These professionals remained calm, executed their procedures, and relied upon sound CRM to land (or ditch) their aircraft. Events like these do not make the evening news, but they should be celebrated as they illustrate preparedness and disciplined execution in the face of exceptional adversity. Viewed through that lens, there are legends all around us! By sharing their stories, we reinforce the principles that make Naval Aviation great.

There are also legends among us who have never flown in an aircraft. I have come to realize that once we hang up the flight suit, it will be the impact we had on people’s lives that is remembered—not the programs we managed, our tactical qualifications, or the hours we flew at sea. Those things matter in limited contexts, but they do not change lives. Did you help someone reach his or her potential? Did you create opportunity that would not have existed were it not for your intervention? Did you exude qualities that others chose to emulate? If the answer to any of those questions is “yes,” then you are a legend to someone.

As a young Sailor in the early 90’s, I was lucky enough to cross paths with a Chief Petty Officer who—despite my insufferable arrogance—saw something in me that was worthy of his time. He took a personal interest in my development, and he taught me some important lessons: How to be productive in the workplace, how to set and accomplish goals, and the value of one’s professional reputation. I had nothing to offer him in return other than my admiration, but he set me on a path that led to college, a commission, and a career that continues today. Chief Wells remains a legend in my life.

The profession of arms celebrates the accomplishment of objectives; our legacies, however, will have less to do with the tasks we accomplished and more to do with whether we were honest, forthright, and caring as leaders. It is both poetic and ironic that we often achieve this clarity just as the window to our influence begins to close. As we approach the Symposium in May, we should continue to pay homage to the giants who went before us…the heroes, heroines, and true legends of Naval Aviation. We should also realize that the potential to be legendary exists in all of us—whether inside or outside the aircraft. We must not lose sight of our potential to meaningfully change the lives of others; it requires little more than conscious effort. Given that most of us will never do anything truly heroic in the aircraft, I think it is a legacy worth pursuing.

Rotor Review #160 Spring '23 16 Commodore's Corner

Your Legacy

By LT Alden “CaSPR” Marton, USN

Typicalscuttlebutt revolves around our growing pains without deference to the amazing work currently being done to increase the scope and influence of the U.S. Navy. Let’s all take a pause to recognize the talent in which we find ourselves. All of us can be pioneers of our platform. Every time you strap into a gray war machine, fire up the APU, and cut through the skies you are searching for perfection in flight. If that means seeking perfection in execution, you’re pioneering excellence. If your goal is to attempt something new (within limits of course!), you’re pioneering innovation. If your goal is operational success, you’re making history. Given the right amount of opportunity combined with the passion for flight, we all have the ability to make waves through generations of pilots and aircrew. A few of our peers have done just that and have been able to make a lasting impact on the Naval Aviation Enterprise (NAE). Take a reflective moment to ask yourself “am I making my own legacy?”

If you get the opportunity to take a job that “hasn’t been done before,” take it. See how far you can run with it. See what you can create. Pilot and aircrew tactics are being developed for emerging platforms in the V-22, TH-73, MQ-8, etc. Squadrons are being stood up as we speak. One day, 50 years from now your name might not be plastered against the walls (except at the OClubs!), but what you develop today will save aircraft and save lives. It will become part of the community’s bedrock and THAT is our legacy.

If you don’t know where to begin your own journey, use NHA Symposium to find those opportunities. You’ll get face-to-face time with legends from the Vietnam War and the Navy’s rich cultural history. You’ll have a chance to hear from Naval leadership about the state of the NAE, from titans of industry on the forefront of technology, and your peers. Focus on those candid discussions. Can you identify soft spots in our capabilities? Is there something that needs to be done better? With a little bit of proactivity and a little bit of timing, you can be the one to turn that weakness into a strength and start solidifying your own legacy. It starts by getting the right people in the room and having open discussions, and that’s what this Symposium aims to do.

The 2023 NHA Symposium: Forging Legacy – Legends Past and Present is now open for registration. Can’t wait to see you all there at Harrah’s Casino in May!

Fly Navy! CaSPR

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 17

NHA JO President Update

Naval Helicopter Association Scholarship Fund

Donate and Apply

By CAPT Arne Nelson, USN (Ret.), President NHASF NHA LTM #4/RW#13762

Shipmates!

Greetings from the Scholarship Fund. We are in the middle of our 2023 scholarship selection process with 52 eligible candidates from a field of over 70 total applicants. With candidates from each geographic region, including a special category for active duty military members and spouses, we have one of the strongest competitive fields of applicants in recent memory. This year, following our 5-year strategic plan, we ratcheted up the scholarship value to $4,000 for each of the 15 scholarship awardees.

Since the selection results will not be available before this issue goes to print, we will announce the 15 scholarship awardees at the National NHA Symposium and post the winners, along with their corresponding scholarship and destination university, in our follow-on Rotor Review Summer Issue. Stay tuned.

2022/2023 Fundraising May Have Been Our Best Year Yet

Categories for funding continue to show the generosity of both past and present donors. This year we have already exceeded our fundraising goals for 2023. Our sources of income have grown, particularly in the memorial and legacy categories.

Individual donations increased with the focused Day of Giving Campaign and the Annual Golf Tournament. Our individual donor list continues to grow to over 90 donors, with the average gift exceeding $250.

Corporate sponsorships (annual and in perpetuity) include Leonardo Helicopters (U.S.) (new), Lockheed Martin (new), Naval Helicopter Association, Raytheon STEM (in perpetuity), Teledyne FLIR, and the USS Midway Museum.

Legacy donations and Memorial passthrough gifts were based upon generous donations in perpetuity made years ago. Others are just starting, including Big Iron (HM/HC Heavy Lift) Legacy, HS-5 Night Dippers (CAPT Root and CAPT Resavage Memorial Scholarships), Charles Kaman Memorial, Friend of Navy Helicopters Dominic Sargiotto, NHA Historical Society (Mark Starr), Ream Family Memorial, and Teledyne FLIR Memorial.

The Investment Income portfolio, generated from the initial donations of Don Patterson Associates, remains strong enough to skim and fund a few full scholarships or add plus-up funds as needed. However, since the market remained unpredictable, and with the strong performance of other categories of donations, we did not need to tap the investment portfolio.

I look forward to your support in the 2023-2024 scholarship rounds and at the upcoming NHA Symposium, 17-19 May 2023 at Harrah’s Resort, Southern California.

Rotor Review #160 Spring '23 18

The End of an Era Farewell to the Vanguard of HM-14

12 May 1978 - 30 March 2023 and Remembering 40 years of Heavy Lift HC HC-4 Black Stallions

6 May 1983 - 28 September 2007

Donate to NHASF’s Big Iron Legacy/Memorial

With the disestablishment of the historic HM-14 Vanguard fresh in our memories, take a moment to recall the 40th anniversary of the establishment of the Navy’s first Heavy Lift Helicopter Squadron, the Black Stallions of HC-4 on 6 May 1983. Arriving at NAS Sigonella, Italy on August 25, 1983, the "Black Stallions" established themselves as the "prime movers" of air-delivered cargo in the Mediterranean and the Middle East. The Black Stallions provided heavy combat support throughout Europe, Africa, and the Middle East in every conflict, major naval operation, and exercise throughout the squadron’s service. HC-4 redeployed to Naval Station Norfolk in 2005–2006 and was disestablished on 28 September 2007.

As veterans and former HM / Heavy Lift HC / H-53 Bubbas, linking back to the earliest days of HM in 1970, I request your support to grow our scholarship fund. Through a generous gift from a former shipmate, a fund has been established to provide one of the NHA Scholarship Fund’s 15 scholarships each year. As you reflect on the legacy of the Vanguard and the Black Stallions, please consider donating to the newly established “Big Iron” Memorial Scholarship (RH-53D 158759 DH-25) to preserve the legacy of our community and its heroes with either an annual “pass-through” scholarship or in time, establishing a “Big Iron” scholarship in perpetuity.

Also, consider re-joining or extending your current membership in the NHA as a new Lifetime Member.

Arne Nelson, Captain, U. S. Navy (Ret.) President, NHA Scholarship Fund

NHA LTM #4 Rotary Wing # 13762

P.O Box 180578

Coronado, California 92178-0578

(619) 435-7139 Office / (619) 607-0800 Cell

The NHA Scholarship Fund is a 501 (c) (3) nonprofit charitable California corporation: TAX ID # 33-0513766. Thanks for your support!

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 19

Naval Helicopter Association Historical Society

Happenings at NHAHS

By CAPT Bill Personius, USN (Ret.), President, NHAHS LTM#46 / RW#16213

Welcome to the Symposium Edition of the Spring 2023 Rotor Review. The Symposium theme is “Forging Legacy - Legends Past and Present.” This year’s Symposium, I am sure, will prove to be bigger and better than those in the past. I hope that you will enjoy the professional and social events that are planned.

I am pleased to announce that NHAHS has received the approval to go forward with the CDR Clyde E. Lassen, USN (Ret.) SH-60F Memorial Medal of Honor Display Aircraft at the NASNI Front Gate from the Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Energy, Installations and the Environment (ASN EIE). Click here (https://sh60fhoas.navalhelicopterassociation.org/nasni-helicopter-on-a-stickpowerpoint-brief/ ) for the project background.

CAPT “Bomb” McKissick (CO, NASNI) has signed the transfer document and I have paid Davis Monthan to have the aircraft moved out of the Bone Yard to North Island to be inducted into the USS Midway Restoration Hangar 805. The transfer is scheduled to happen April 24, 2023.

I would encourage your support getting the word out about the project and assisting with the fundraising efforts. I am meeting with contractors this week and will obtain more accurate cost estimates; however, it looks like we will need ~$150K+ to complete the project. What I am asking is for you to reach out to your contacts who may be willing to help. Sikorsky and GE have already made donations. Please consider writing a check to NHAHS or make a secure donation via the web HERE to help with the project. Get your name on a brick (and encourage others) that will be built into the base of the stanchion so your contribution will live on this memorial to Clyde Lassen and his crew well into the future.

Checks can be mailed (preferred donation method) to:

NHA Historical Society, Inc. (NHAHS)

P.O Box. 180578

Coronado, CA 92178-0578

NHAHS will appreciate your support in helping with the fundraising efforts and making a donation toward the project. In the future, everyone who passes through the front gate will enjoy seeing the aircraft when the project is completed and do so for many years to come. Consider having a brick with your name and a logo on it built into the base of the display. After all, NASNI is a Master Helicopter Base and there should be a helicopter at the front gate recognizing a Rotary Wing Medal of Honor Recipient and Hero like CDR Lassen across the street from VADM Stockdale’s A-4 Skyhawk.

I look forward to hearing from you and receiving your donation and hopefully seeing you at the NHA Symposium 17-19 May.

NHAHS is working with the Scholarship Fund to host the Golf Tournament, present the Mark Starr Pioneer Award, Gold and Silver Crew Chief Awards and man a booth paying tribute this year to:

• 50 Years of Women Flying in Naval Aviation

• 55 Year Anniversary of the Lassen Rescue

• 80 Years of Naval Helicopters

• 100 Year Anniversary of Sikorsky Aircraft

Stop by Booth # 104 and see us!

Keep your turns up!

Warm Regards,

Bill Personius

CAPT USN (Ret.) LTM-#46, R-16213 President

Naval Helicopter Association Historical Society (NHAHS)

Rotor Review #160 Spring '23 20

PayPal Donation Link

Computer Rendition of NASNI Stockdale Entrance with SH-60F on a Pedestal

Mail Checks to: Naval Helicopter Association Historical Society, Inc. (NHAHS) NASNI SH-60F Project PO Box 180578, Coronado, CA 92178-0578

To donate with PayPay visit https://www.nhahistoricalsociety.org/indexphp/donations/ and click on the PayPal icon or copy and paste this link in your browser https://www.paypal.com/donate?token=dUz7iSsDDUkFxuXCIsSpZE5lRrmAZ7M5diK1LRJ315ULqrsnyvU3nuz4WHPu0z4ZBCW7xiw34NubTIs

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 21

Accelerating Rotary Wing Innovation Through Unmanned Systems

By CAPT George Galdorisi, USN (Ret.)

One of the great things about working at a Navy Warfare Center, such as Naval Information Warfare Center Pacific, is that you have the opportunity to see new technologies envisioned, created, and, in many cases, implemented into the Fleet or Fleet Marine Forces. With over 5,500 government employees, and an equal number of contractors, our warfare center is involved in a breathtaking number of projects.

Increasingly, given the U.S. Navy‘s commitment to unmanned systems and the Chief of Naval Operations’ vision of a hybrid fleet comprised of 350 manned vessels and 150 Unmanned Maritime Systems (UMS), a great deal of our work has focused on unmanned systems in all domains: air, surface, subsurface and ground.

The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan accelerated the development and use of Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS) and Unmanned Ground Systems (UGS), however, the development of unmanned systems in other domains has fallen behind. The Navy has now shifted focus to the development and fielding of multi-mission UMS. To aid in that development, Fifth Fleet established CTF-59 to experiment with UMS and UAS and accelerate their development and fielding.

In late 2022, CTF-59 orchestrated Exercise Digital Horizon. This multinational exercise featured 12 Unmanned Surface Vehicles (USVs) and three UAVs, linked using artificial intelligence, to push the boundaries of these platform’s contributions to important naval missions, especially Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA). The importance of Digital Horizon 2022, and a view of what would be accomplished, was highlighted by one naval analyst this way:

Despite the cutting-edge hardware in the Arabian Gulf, Digital Horizon is far more than a trial of new unmanned systems. This exercise is about data integration and the integration of command and control capabilities, where many different advanced technologies are being deployed together and experimented with for the first time.

The advanced technologies now available and the opportunities that they bring to enhance maritime security are many-fold, but these also drive an exponential increase in complexity for the military. Using the Arabian Gulf as the laboratory, Task Force 59 and its partners are pioneering ways to manage that complexity, whilst delivering next-level intelligence, incident prevention and response capabilities.

Digital Horizon 2022 brought together emerging unmanned technologies with data analytics and artificial intelligence in order to enhance regional maritime security and strengthen deterrence by applying leading-edge technology and experimentation in unmanned and artificial intelligence applications for the Navy. A key goal of Digital Horizon 2022 was to speed new technology integration across Fifth Fleet, and seek alternative, cost-effective solutions for conducting MDA missions.

Digital Horizon lived up to the high expectations of all involved. Vice Admiral Brad Cooper, Commander of U.S. Naval Forces Central Command, U.S. Fifth Fleet, and Combined Maritime Forces described what was accomplished during Digital Horizon 2022 thusly:

We are creating a distributed and integrated network of systems to establish a “digital ocean” in the Middle East, creating constant surveillance. This means every partner and every sensor, collecting new data, adding it to an intelligent synthesis of around-the-clock inputs, encompassing thousands of images, from seabed to space, from ships, unmanned systems, subsea sensors, satellites, buoys, and other persistent technologies.

No navy acting alone can protect against all the threats, the region is simply too big. We believe that the way to get after this is the two primary lines of effort: strengthen our partnerships and accelerate innovation. One of the results from the exercise was the ability to create a single operational picture so one operator can command and control multiple unmanned systems on one screen, a Single Pane of Glass (SPOG). Digital Horizon was a visible demonstration of the promise and the power of very rapid tech innovation.

Rotor Review #160 Spring '23 22

View from the Labs

Elbit Systems Seagull unmanned surface vessel operates in the Arabian Gulf, Nov. 29, during Digital Horizon 2022. U.S. Army photo by Sgt. Brandon Murphy)

The results of Digital Horizon 2022 could change the way the world’s navies conduct maritime safety and security. Artificial Intelligence and machine learning are able to amalgamate the sea of data created by unmanned systems into actionable, realtime intelligence for use by commanders, which enables U.S., allied and partner nations to dedicate their crewed vessels to other missions.

Using a two billion dollar ship and a crew of 300 officers, chiefs, and sailors to conduct surveillance operations is not a cost effective solution when a medium-sized commercial offthe-shelf (COTS) USV (such as a MARTAC Devil Ray T-38, one of the participants in Digital Horizon) can be bought or leased in a contractor owned, contractor operated (COCO) arrangement for a relatively modest cost and equipped with state-of-the-art COTS sensors to provide persistent surveillance. During Digital Horizon, the T-38 provided AIS, full motion video from SeaFLIR-280HD and FLIR-M364C cameras, as well as the display of charted radar contacts via the onboard Furuno DRS4D-NXT doppler radar. These were all streamed back to Task Force 59’s Robotics Operations Center (ROC) via high bandwidth radios. The force multiplying potential of unmanned systems demonstrated during Digital Horizon has already been recognized by the Naval Aviation Enterprise (NAE) and the rotary wing community.

So why is this important to us? For those of you who attended the 2021 NHA Symposium and listened to the Flag Panel, you heard that Naval Aviation is on a glideslope to be approximately 40% unmanned circa 2035. Though exact timelines and percentages are impossible to predict, the unmanned future is coming, spearheaded by the MQ-25 Stingray, the MQ-4C Triton and MQ-8C Fire Scout leading the way.

The Fire Scout is currently the Rotary Wing Community’s only “skin in the unmanned game,” and though the MH-60S Knighthawk and MQ-8C Fire Scout are currently embarked onboard Littoral Combat Ships (LCS), where Rotary Wing Aviators and Surface Warfare Officers are developing CONOPS for their use together, the Navy is scaling back its inventory of LCS. This will shrink the opportunities for our community to explore tactics, techniques and procedures to develop man-machine teaming or to develop Fire Scout “smart wingman” in the same fashion that the U.S. Air Force is doing with the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter and emerging UAVs.

In remarks at the December 2022 Reagan National Defense Forum, Secretary of the Navy, Carlos Del Toro, said that the Navy intends to stand up additional unmanned task forces around the globe modeled after Task Force 59, noting:

We’ve demonstrated with Task Force 59 how much more we can do with these unmanned vehicles—as long as they’re closely integrated together in a [command and control] node that, you know, connects to our manned surface vehicles. And there’s been a lot of experimentation, it’s going to continue aggressively. And we’re going to start translating that to other regions of the world as well. That will include the establishment of formal task forces that will fall under some of the Navy’s other numbered fleets.

The Naval Rotary Wing Community needs to be part of this emerging technology development, lest we be left behind as the Navy and NAE place huge bets on a force increasingly populated by unmanned systems. As to how we can do this, those of you wearing flight suits are best-qualified to develop new concepts for how our community can leverage rapid developments in unmanned systems in all domains to ensure that we have a warfighting advantage in future conflicts.

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 23

In this issue: No legends started out that way and most never intended to be legends at all. Some are world renown, while others are only recognized in their own spheres of influence.

Who are those individuals that made our naval rotary wing community what it is today? What qualities make a legend? Have the qualities we value in those we hold at the highest regard changed over the years? Who are our modern-day legends and how do they differ from our legends of the past?

The Legacy of the Navy’s Helo Master Plan, Circa Early 2000’s

By VADM Dean Peters, USN (Ret.)

By VADM Dean Peters, USN (Ret.)

Whoare those individuals that made our naval rotary wing community what it is today? What qualities make a legend?

I’ve thought long and hard about this radio check. It’s so true that we stand on the shoulders of those who have gone before –and indeed many have been foundational in making the rotary wing community what it is today. Our forebears broke many glass ceilings and forged viable paths to flag officer and master chief petty officer that allowed others to follow. Along the way, they developed new tactics and innovative ways to employ rotary wing assets. Our enlisted rescue swimmers transformed a secondary occupational specialty into one of the most revered career fields in the world. With recognition of strong leadership, opportunities at the senior levels of the Navy began to emerge: ship CO’s; key BUPERS positions; OPNAV Financial Management positions; Expeditionary Strike Group Commanders; and Carrier Strike Group Commanders.

One important aspect of our Navy legacy involves the aircraft and weapons systems employed by the rotary wing community. Aircraft programs in and of themselves won’t deter would-be competitors or win in combat. But capability and readiness start with aircraft programs and the budgets that enable them. In essence, having the right equipment gets you into the fight in a direct role and makes your community relevant. The man, train, and equip mission enables combat effectiveness. In keeping with the theme of this quarter’s focus, and subject to the limitations of memory, I’d like to provide a few notes on this aspect of our legacy and call out one leader who truly transformed Navy rotary wing aviation and put us in a position to be relevant for decades.

Since the early days of rotorcraft, aircraft have been adapted for emergent needs, from crew-served weapons and mine sweeping equipment during the Vietnam era to the Middle East Force mods for Persian Gulf operations in the late 1980’s. Recognizing the versatility of rotorcraft, the Navy began procuring rotorcraft for specific operational missions in the 1970’s, such as the MH-53E for Airborne Mine Countermeasures and the SH-2F and SH-60B for the Light Airborne Multi-Purpose System (LAMPS). LAMPS was developed specifically for integration with surface combatants, effectively enhancing and extending the ship’s sensors. The SH-60B was the successor to the SH-2F LAMPS platform, although both platforms were operated concurrently for about a decade. The SH-2G was developed in the late 1980’s and tested for employment on nonRAST surface combatants. It would ultimately be fielded with the Navy Reserves. Other aircraft types provided specific mission capabilities such as inner zone ASW, combat logistics support, search and rescue (land and sea), combat search and rescue, and special warfare support. At certain times in the 1990’s, Navy active and reserve squadrons were operating, or preparing to operate, a variety of helicopters: HH-1N’s, SH-2F’s, SH-2G’s, SH-3H’s, UH-3H’s, CH-46D’s, MH-53E’s, SH60B’s, SH-60F’s, and HH-60H’s. The squadrons were distributed under HC Wings, HS Wings, HSL Wings, and an HM Wing, each with peculiar purviews and differing cultures. These many type wings were further organized under separate east and west coast command structures, again with differing purviews and mission responsibilities.

Rotor Review #160 Spring '23 24

Radio Check - Legends

With the massive drawdowns of the 1990’s, maintaining such a large number of communities and platforms became unsustainable, especially considering available manpower. And because of the dispersed organizational constructs, developing a single Navy rotary wing voice was nearly impossible, creating an environment where the helicopter communities could be inadvertently (or intentionally) picked apart in the competition for resources. This was a crucial time for the rotary wing community writ large, and happily, our forebears put aside their platform-specific biases (for the most part) and banded together to develop a vision for the future. Joining them were several dynamic resource sponsors who would authenticate this vision through rigorous analysis, and then carry it forward into budget deliberations, campaigning relentlessly throughout the OPNAV Surface Warfare and Air Warfare Directorates. This was the Helicopter Master Plan, commonly known as the Helo Master Plan, and it was supported by the Helicopter Concept of Operations. The Helo CONOPS was itself visionary, involving a rigorous technical analysis of future fleet operations that required rotary wing assets. It was future-leaning and included strike group requirements, expeditionary requirements, and forward deployed requirements. The Helo Master Plan was informed by the Helo CONOPS and provided an agile, schedule-based transition plan to consolidate Type Wings and reduce seven T/M/S to two, while satisfying fleet needs in an efficient and effective manner. Specifically, the following T/M/S would be retired: SH60B, SH-60F, HH-60H, CH-46D, SH-3H, SH-2G, and HH-1N. Missions performed by these aircraft would be performed in the future by suitably-configured multi-mission helicopters, the MH-60R and MH-60S. In addition, the MH-53E would either transition AMCM mission responsibilities to other T/M/S and minesweepers, or require development of a new aircraft. Part of the beauty of the Helo Master Plan was the simple messaging: consolidation of seven T/M/S to two T/M/S and parallel consolidation of type wings and associated staffing, while increasing combat capability. The construct allowed the number of squadrons to evolve with carrier airwing, surface combatant, and expeditionary requirements. This messaging was incredibly important because it would be used to frame the largest investment in rotary wing assets in the Navy’s history, the Programs of Record for the MH-60R and MH-60S, including Block upgrades.

In keeping with the themes of legacy and legends, I want to call out one leader who was particularly responsible for the ultimate success of this vision. It was his articulation of the problem and tireless coordination that galvanized his peers across many communities to produce a single voice. The leader I’m talking about is Captain George Barton who was then Commander, HSL Wing Pacific. As a Commodore in San Diego, he was in close proximity to his HC and HS counterparts, allowing frequent engagements. He also made numerous trips to Norfolk, Jacksonville, Mayport, and the Pentagon to engage the east coast communities and resource sponsors. Importantly, he made sure that everyone in the community was informed. Commodore Barton exhibited several qualities that were critical to the success of the Helo Master Plan:

(1) He described the problem and asked for help determining the solution, seeking feedback from all stakeholders. There was no ego, no pride of ownership, and the plan was continuously refined to achieve convergence. This would be a team effort.

(2) He understood the importance of underpinning the plan with rigorous analysis and used the analytical results to build compelling warfare-related arguments. In this regard, he was ahead of his time.

(3) He prioritized the human element and ensured that transitions would be accomplished in a way that maximized career progression and command opportunities.

The complexity of this transformation was unprecedented in rotary wing history and as mentioned, it also involved a historic investment in aircraft and weapons systems. The above qualities, capably exuded by Commodore Barton, created the tide that raised all boats. Although many were involved in crucial roles, Commodore Barton was our quarterback.

Looking across the current fleet, I contend that these qualities are evident and still valued in today’s rotary wing leadership. Our warfare communities work together collaboratively to determine and present budget priorities, applying analytical rigor to determine mission needs. I’ll go so far as to say that no other community in Naval Aviation is as analytical as the rotary wing community, and no other community is as articulate in describing proposed solutions to evolving mission requirements. Lastly, the rotary wing community continues to prioritize people. As unmanned systems are integrated and as squadrons stand-up, transition, or sun-down, you can be sure that every effort is made to take care of our most precious resource – the men and women who serve in the rotary wing community.

So, as you look up and down the rows of aircraft on the flight line and consider the myriad of capabilities that our squadrons bring to the fight, I hope you’ll be aware of the foundation that made it happen. And think about leaders like Commodore George Barton, a true legend in the rotary wing community.

www.navalhelicopterassn.org 25

CAPT George Barton, USN (Ret.)

From Ralph Deyo

Okay, have I got a True Legend for the readers. This man not only made me look forward to a new assignment and a really sucky one at that, but he made me look forward to a total change in my career. But let’s start from the beginning of this tale of a True Legend.

In June 1971, I left wonderful Oahu, Hawaii and the greatest Patrol squadron in the Pacific Fleet, VP-17, and headed for FASOTRAGRUPAC at beautiful NAS North Island

I was assigned to VS Acoustic Analysis Training and performed well during the first six months, and was even awarded an Instructor of the Quarter Letter in 1972. So, I am feeling pretty good about myself and how I am doing as a new instructor. By the way, I finished the five week instructor training course in five days.

About a week after I received the recognition letter, I was summoned to the CO’s Office. I arrived at the appointed time and was invited to sit down alongside another Captain. This Captain asked me how things were going, my job, my new wife, and how I liked the San Diego area. Somehow I knew that there was something up his sleeve and he pulled out a good one. The Legend at the time was on staff at COMASWWINGPAC.

“Petty Officer Deyo, have I got a deal for you. How would you like to assist in setting up a new training program?” My response, “Oh sure Captain, what is it and when does it have to be online?”

Now comes that career changing part.

It is going to be at Ream Field, and it will be the Aircrew Training Facility for LAMPS MK I. LT Jerry Bunch will be your OIC (a great OIC who did get me a lot of SH-2F flight time and many emergencies).

So, here I am in a dilapidated WWII building with AW1 Neal Brown and AW1 Smith, rehabbing the building with a couple walls, new tiled floors, and several gallons of paint. We begged and borrowed enough equipment to set up a Lab for the ASA20, MAD Recorder, and even had a live radiating LN-66 Radar on a 40 ft pole. All in a six-month time frame.

I instructed Aircrews in the operation of this equipment for three years and then the most horrific event in my naval career happened.