14 minute read

PEP, Part 2: Left Pedal or Right Pedal?

LT Randall A. Perkins, USN

MH-60S Knighthawk vs AS365 Dauphin

Advertisement

In “PEP, Part 1” (Rotor Review #153), I provided an in-depth look at the Personnel Exchange Program (PEP) and its requirements for selection. In this article, I will shift focus from the administrative and academic side of the program to the actual flying. We’ll focus specifically on maintaining proficiency while at DLI, flight prep prior to a flying PEP Tour, an introduction to the AS365 Dauphin, and how the Dauphin compares to the MH-60S.

Flight Proficiency at DLI & Flight Prep for a PEP Tour

Any pilot prefers to be in the cockpit rather than behind a computer, staring at a tracker of another tracker in Microsoft Excel. Unfortunately, while attending DLI you’ll be a full-time student studying the language day in and day out. But depending on the PEP Tour you have selected, there might be an introductory “CAT I” FRS-Type Syllabus for you when you arrive. In an ideal world, every single PEP pilot would complete some such a syllabus upon arriving at their PEP unit, or perhaps (best case scenario) receive some sort of stateside training prior to moving overseas after completion of DLI if a similar T/M/S aircraft exists. Despite seeming almost like a hard-set requirement, not all flying PEP tours will include this training. For example, PEP Toulon does not include a stateside H-65 FRS in the orders, or a French FRS upon arrival. The initial syllabus for PEP Toulon is essentially a combination of an HTs/FRS/H2P syllabus upon your arrival to the unit. This can feel a bit overwhelming, especially because the training is conducted in a foreign language! Allin-all, it is likely that most will arrive at their PEP units not having flown in the past year, and feeling quite rusty. PEP selectees can take comfort in the fact that, whether it’s made by Sikorsky or Airbus, a helicopter is still a helicopter.

If you’d like to maintain some sort of aviation preparedness or “readiness” while attending DLI, you can always attempt to join a flight club nearby (check out Monterey Regional Airport). If you’re lucky, you might even have the opportunity to work with a nearby Naval Aviation unit to maintain some sort of proficiency. For example, NAS Lemore is just a fewhour drive from DLI in Monterey. Prior to reporting to DLI, I was fortunate enough to re-base my annual NATOPS Instrument check rides. This was significant in allowing me to maintain proficiency with a nearby MH-60S unit and therefore arrive at my PEP unit in a “current” status. A realworld example of the U.S .Navy re-basing an “exchange/PEP '' pilot prior to sending them overseas is displayed in the United States Navy Test Pilot School (USNTPS) exchange billet with the French TPS, EPNER. At the present time, the US Navy sends a TPS pilot to the French Test Pilot School every third rotation (every third pilot). Prior to reporting overseas, and post-DLI, this pilot goes through a condensed TPS Syllabus in Pax River, MD to prepare them for their tour at French TPS. They’ve likely just come off of almost a year without flying, and rather than send a rusty aviator overseas, the U.S. Navy elects to provide them with an opportunity to prepare. This is a fantastic idea and process which allows us to send a refreshed aviator overseas.

Now timing, career milestones, nine-plus months of language learning, and other factors largely prohibit this icing on the cake for every flying PEP Tour. But if you’ve just finished a flying tour prior to DLI, you’ll do just fine. It will be painful at first but eventually you will become comfortable, or at least comfortable enough, with flying a foreign aircraft in a foreign language.

Note: Orders to the DLIFLC are DIFDEN and not DIFOPS. A flight waiver will be required if you wish to fly with a Naval Aviation Unit. I recommend looking ahead, coordinating with the unit, and submitting the waiver early.

AS365 N, F, N3 – Intro to the Dauphin

My PEP unit flies three Dauphin variants. The Dauphin N, the Dauphin F (nicknamed “Pedro”), and the N3. On top of these, the N3 has slight variations. Certain detachments of the PEP unit stationed at outlying French territories fly the N3+. The base model for all of these aircraft is the Dauphin, but the avionics, engines, and autopilot functions vary across the platforms.

Big Sur, CA

Dauphin “Pedro”

At its base, the Dauphin is a twin-engine aircraft with two free-turbine turboshaft Arriel engines, a rigid STARFLEX rotor head with four composite material blades and a tail rotor fenestron. The engines vary from aircraft to aircraft as follows: Dauphin N – Arriel 1C, Dauphin F – Arriel 1MN, and Dauphin N3/N3+ – Arriel 2C. The maximum gross weight of the aircraft is anywhere between 4000kg and 4300kg depending on the model, with the N3/N3+ boasting the highest gross weight and power availability. The Dauphin, built by Eurocopters (now Airbus), entered service in 1975 and will continue flying in the French Navy until the year 2030, at which point it will be replaced by the Airbus H160. The Airbus Helicopters headquarters is currently located in Marseille, FR, which is also home to their helicopter simulators where pilots from across the world conduct much of their training.

Each model of the Dauphin serves a different purpose for “La Flottille 35F,” the French squadron here in Hyeres, France. The Dauphin N is a 3-axe autopilot aircraft with minimal avionics and a weather radar. It serves as a SAR asset for the coastal detachments and as a training platform for the home guard unit in Hyeres. The Dauphin F is the designated “PEDRO” asset, or the SAR aircraft for the Charles de Gaulle French Aircraft Carrier. It sports a 4-axe autopilot, improved radar for SAR, weather, Helicopter Control Approaches (HCA), and more. The N3 is the primary “service publique” asset for Hyeres. It’s equipped with improved engine performance but only a 3-axe autopilot, basic weather radar, and no doppler. The N3 fulfills what Americans would refer to as a “SAR Alert,” or coastal SAR mission. An aircraft and crew are on alert 24/7 with varying recall hours. Finally, the N3+ is a specific aircraft reserved for the French Territory of Tahiti. The mission of this detachment is most like that of HSC-25, which operates out of Guam and serves as the primary SAR asset for the island. This model is also closest to the MH-60S in terms of power and capacity with a full autopilot, enhanced radar, and a doppler system. All aircraft except for the N3+ are mostly “steam” gauges with cockpit configurations usually being asymmetrical between pilots due to the installation of a radar screen on one side. This can make some maneuvers and regimes, including IFR flight, a bit challenging due to the cross-cockpit scan.

CAT A & B – Intro to the Dauphin

As a smaller aircraft, the Dauphin is extremely nimble, but you are often taking off near your max gross weight if loaded with a complete SAR crew and full bag of gas. The habit of taking off heavy with underpowered engines leads to a large emphasis on single engine failure procedures here amongst the French Dauphin Community. Depending on your gross weight and performance characteristics, your takeoff profile, abort takeoff speed, and landing profile can vary drastically. In the HSC Community, this is a simple discussion of power margin that leads to the decision to conduct either a normal takeoff from a helicopter pad, a running takeoff, or a max gross weight takeoff. Here, it is a bit more complex.

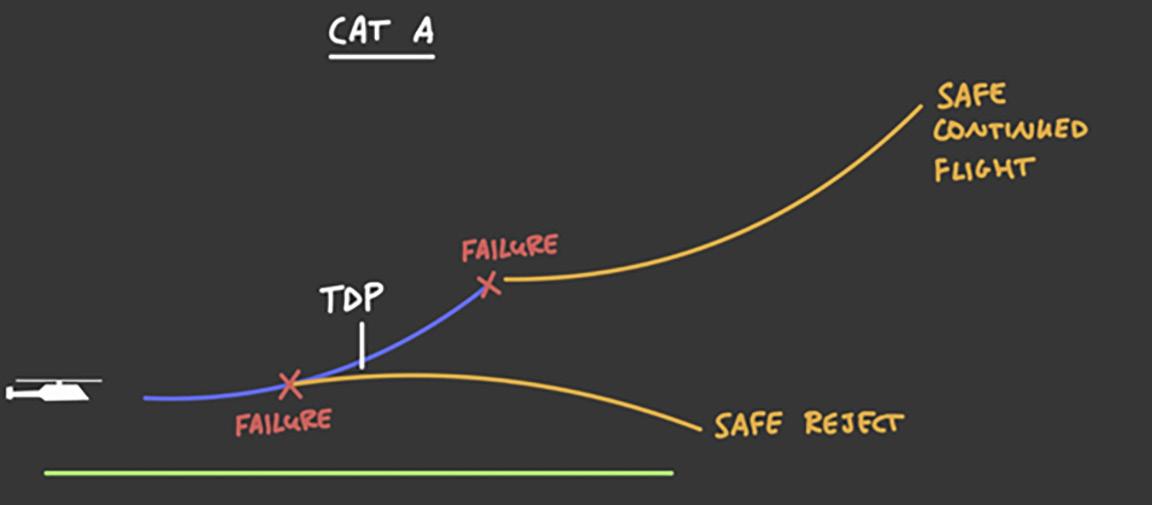

General knowledge amongst the civilian helicopter community in the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) and amongst the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) is that helicopters can be categorized (certified) as either CAT A or CAT B. This certification is at the level of aircraft manufacturer, which adheres to certain levels of compliance for each category of aircraft. The difference between CAT A and CAT B is in the ability to continue safe flight in the case of engine failure. A helicopter certified as CAT A is a multi-engine helicopter that has the capacity to either interrupt the takeoff and land safely due to engine failure, or continue safe single-engine flight. A helicopter certified CAT B does not meet CAT A standards (single engine or multi engine) and thus has no guaranteed margin of safety. Essentially, in the event of an engine failure, continued safe flight is likely not possible. Furthermore, Category A helicopters may operate in Performance Class 1, 2 or 3, but Category B helicopters may operate in Class 3. Operation in a specific performance class is determined by the performance data in a specific situation and location. Essentially, you can think of Class 1 as being able to “fly away” after an engine failure during takeoff (based on performance data, length of runway, etc). Class 2 is expected not to be capable of continued single engine flight during takeoff or landing (i.e. Class 3) but capable of continued single engine flight during the climb, cruise, or descent. And Class 3 refers to aircraft in which, if an engine failure occurs during any phase of the flight, a forced landing may be required in a multi-engine helicopter and will be required in a single engine helicopter. Whether an aircraft is certified CAT A or B and which performance class it falls into for that day will alter the type of takeoff or landing procedure conducted. Moreover, to make things more confusing, depending on the type of runway, helicopter pad, and obstacles present, the takeoff profiles vary between CAT A and CAT B. To simplify, if the Dauphin is under a certain gross weight, it may conduct operations as a CAT A certified helicopter, and IF it meets the performance requirements it may conduct the takeoff and landing using Performance Class 1 procedures. If it has the mass but not the performance, it will conduct operations in Performance Class 2 which alters the abort takeoff speed and procedures to conduct if an engine failure occurs. At the basic pilot level, figuring out which category and performance you will be operating in will determine what type of takeoff you will conduct, the abort or continued takeoff airspeed, and lastly, how you will react in the case of engine failure.

CAT A depiction from https://pilotswhoaskwhy.com

Why the difference for the Dauphin?

The Dauphin operated by the 35F is considered a civilian airframe and thus operates under a blend of these civilian parameters (EASA) and a military exception that allows operations in CAT B or lower Performance Class if required. While “we” (the HSC Community) operate a military aircraft under military rules and regulations. To summarize, in the MH-60S we have the luxury of not thinking twice about a takeoff from the nearest helicopter pad, as long as we have the power margin. In the Dauphin Community, 90% of the takeoffs are conducted via the runway. These are accomplished by accelerating from a hover to 70 kts at an altitude of 20 feet. This profile allows for quick-stop takeoff interruption, if necessary, due to engine failure, or a single engine climb at the decision airspeed of the day based on performance numbers. This discussion now leads us into initial differences between the MH-60S Knighthawk and the AS365 Dauphin.

65 vs 60 Initial Differences

Piloting – Remember when you were growing up you would wonder why the toilets in Australia flushed in the opposite direction? It was a big mystery until you grew up, got smart, and thought that it might be attributable to a difference between the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. You would then reference things like the Coriolis Effect, which results in a difference in the direction of deflection of objects between the two hemispheres…only to finally do some research and come to realize that it’s just the water jets pointing in opposite directions…I welcome you to the 60 vs 65. No longer are you leading with left pedal on takeoff as done in the MH-60S. You are now leading with right pedal as you increase the collective. What was once second nature now humbles you back to HTs requiring you take a second, pause, and ensure you are employing the correct anti-torque action. Due to the change in direction of the rotor head (now clockwise, as opposed to counterclockwise) the direction of the anti-torque provided is flipped and therefore the translating tendency is the inverse of that of the 60. Instead of the traditional 10-foot hover with left wing down you are now hovering with right wing down. All the small corrections and piloting skills that seemed to happen subconsciously in the 60 now must be a conscious thought while flying.

Power, Mass, Calculations – The Dauphin F and Dauphin N are power-limited airframes compared to the 60. The aircraft and engines are old, and the gas generator (Ng) can often be the limiting factor for the Dauphin F & Dauphin N. The exception to this limitation is realized in the winter, when torque can start to become a limiting factor as well. In the 60 Community, we often discuss our capacity for internal cargo in terms of torque (“couple” in French) and what margin we will have, not often approaching our Max Gross Weight. In the 65 Community, a mass max takeoff with cargo or passengers (4100kg in the Dauphin F) is commonplace, with the discussion relating more to mass than to power availability for the day. Oddly enough, the power charts for the Dauphin are constructed as mass charts, which rightly assume that the capacity of the engine (Ng) will be altered with a change in the environmental data. These charts will tell you, based on aircraft mass, altitude, and temperature, whether you can take off, hover in ground effect (HIGE), and hover out of ground effect (HOGE). The values in these charts are based on either a continuous Ng limit, or a time-constrained/transitory Ng limit. The power calculations are a bit like tabular data in the 60S Community, but here, we assume that the engine is always performing at 100% for each flight. Hence, the mass calculations assuming a change in Ng for a given altitude/ temperature do not consider or measure engine degradation from flight to flight. The manual does not offer a “1.0” or “.90” engine performance option. HIT checks and power checks, both of which confirm that engines are operating as advertised, are also not performed. What is verified during a “vol de control,” or an FCF, is that a single engine can pull until the elevated single engine Ng limit without drooping (a decrease in Nr). This is similar to the engine checks done for an MH-60S but verifications during the period between “volde control” flights are not conducted nearly as often as they are in the MH-60S Community.

small boat hoisting

Dauphin N3

Airframe – In terms of size, the Dauphin’s total length is approximately 45 feet with a rotor diameter of 39 feet compared to the airframe of the considerably larger MH-60S. The cabin has enough room for six seated passengers, including crew chief and rescue swimmer, but can adjust slightly for more depending on mission and power availability. The fenestron of the Dauphin adds a blanket of security in terms of a complete loss of tail rotor thrust. Because of the fenestron, if a complete loss of tail rotor thrust occurs around bucket airspeed or cruise airspeed, the result is slightly less stable flight with the application of a faster than normal running landing for recovery. Overall, the Dauphin has a very sleek and modern form which has resulted in its sustained performance and longevity as an airframe.

Missions – Several missions of the 35F and the Dauphin align with missions found in the HSC Community to include the following: Search and Rescue, Maritime Surveillance, VERTREP, and Logistics. The 35F prides itself on SAR and hoisting abilities. Where they differ from the SAR missions found in the HSC Community is in their practice of small boat hoisting. Since the 35F also holds the responsibility for coastal SAR, a large portion of their training is focused on this mission. Hoist training occurs on anything from small zodiacs, fishing vessels, and sailing boats to larger ships like those found in the French Navy. Additionally, they assist in the fight against shipping pollution, piracy, and freedom of the seas navigation. As for secondary missions, they are also equally capable of providing special operations support such as fast rope training, parachute operations, and airborne ship defense with a sniper on board.

For any questions concerning PEP or corrections to information stated in this article please contact me, LT Randall A. Perkins IV, at randyperkinsIV@ gmail.com. Follow-on articles will discuss experiences flying in a foreign language, Safety & CRM within French Naval Aviation, and lessons learned for the U.S. Naval Aviation Community. Editor's Note: Photographs were taken by the author.