24 minute read

America’s Playground

AMERICA’S PLAYGROUND

By Dr. T. Lindsay Baker

Advertisement

Almost as old as the automobile itself is the notion of car camping. The 1910s and 1920s saw Americans become increasingly more mobile and venturing out to explore the towns and backroads of America in greater and greater numbers. Those with limited budgets no longer simply remained home but rather sorted out alternative accommodation, opting to furnish their cars with basic camping gear and experience the fresh air of the countryside. Whether tucked up for the night within the vehicle’s steel frame or in a tent adjacent to one’s auto, Americans took up camping out of their car as naturally as they had from a horse. Roadside fields and small-town parks were fair game — unless a farmer took his own “no trespassing” sign seriously. Interestingly, both in the plentiful times of the ‘20s and in the deep depression of the ‘30s, campers were a common sight along U.S. roadways.

After World War II, when steel, rubber, and gasoline were no longer rationed, the American car culture began in earnest, but many motorists still preferred to camp out rather than sleep within the confines of the newly proliferating motels. As this trend continued into the early ‘60s, Montana entrepreneur Dave “Bud” Drum witnessed it, mulled it over, and believed that he could package the experience — with more bells and whistles than most any early 20th Century roadside camper could ever have imagined. A born salesman, Dave Drum stuck his fingers into many entrepreneurial pies. With Purple Heart decorations as a Marine from both World War II and the Korean War, and a business degree earned in between the wars, Drum invested his time and means in a number of money-making schemes. Among other ventures, he ranched, operated cattle feedlots, and manufactured agricultural fertilizer, but most locals in Billings knew him from his exotic pet store and its singular advertising. Emblazoned across its front read the words, “We Sell the Ugliest Monkeys in Town.”

On a wider plane, Montanans across Big Sky Country knew Drum from his term in the Montana State Legislature and other dabbling in politics. No matter how anyone knew him, for decades, everyone had a Dave Drum story, often about his fearless but smart business investments. But one of those investments had a totally different outcome than even he anticipated.

In the early 1960s, Drum invited several friends to partner with him in buying land outside of Billings that Drum suspected the federal government would purchase to develop the interstate. But the new highway went north of his land, and his friends “went south.” Always a visionary, however, Drum foresaw that motorists by the thousands would soon be crossing the nation — with some of them taking the new Interstate 90 — to attend the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair. Just maybe, some would pay for a campsite — with amenities.

KOA is Born

Drum pivoted, recruited three new partners, and developed his tract of land where rural Orchard Lane dead-ended on the banks of the Yellowstone River. Next, the group convinced the city council to extend electric and sewer lines to the site. There, in July 1962, Drum and his cohorts opened their first overnight tourist camp — the Billings Campground — just in time to tempt weary travelers headed to and from the Seattle exposition. Drum and partner John Wallace personally ran the enterprise during its first months in 1962. “When people learn that Billings has a campground with hot showers, running water, and flush toilets, they drive a long way to get to it by night,” Drum declared at the time. That fall, Wallace had the idea to mail paper questionnaires to their summertime The yellow KOA color scheme was used for signs, shirts, and golf carts. vacationers to find out

more about their preferences; he was astonished at the impressive return rate of approximately 50%. A big idea was in sight.

Drum envisioned creating a coastto-coast network of clean, secure, money-making campgrounds, and Wallace encouraged him to go for it. The surveys showed that people were willing to pay $1.75 a night to stay at private campsites that guaranteed guests water, electric, and sewer hookups; clean showers and toilets; picnic tables; and a store selling basic foods and supplies.

Building a Brand

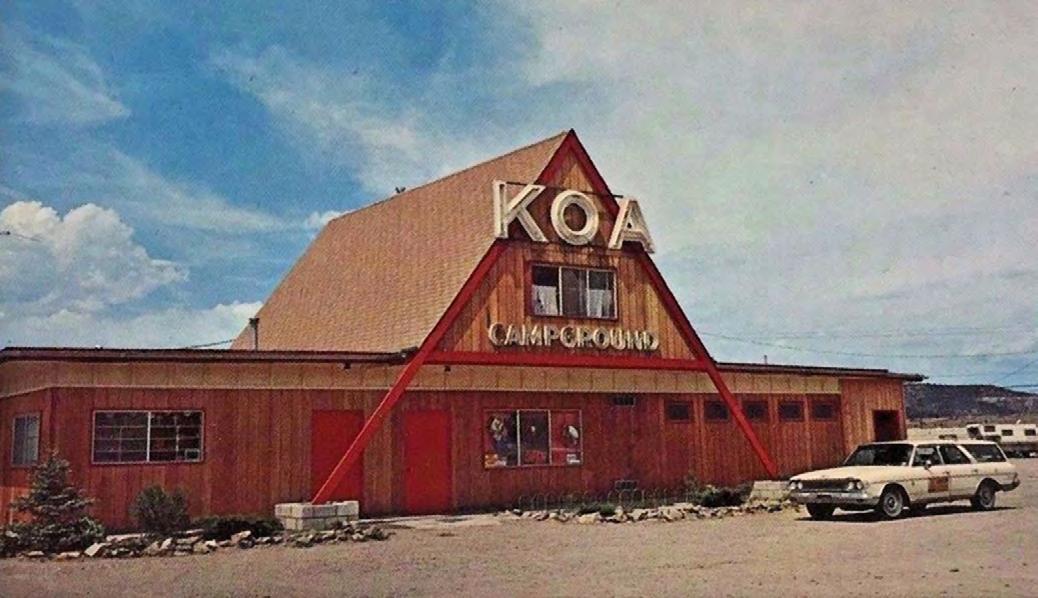

The typical A-frame KOA office and store became instantly recognizable.

Early in the new venture, Drum quickly realized the need for iconic signage and architecture. During a walk along the Yellowstone River, he conferred with Billings artist Karlo Fujiwara about designing what would become an instantly recognizable logo. Fujiwara used lines and dots to create a stylized Indian teepee above the bold KOA block-letter initials — a design that was trademarked in 1963.

“In the logo, the circle at the top represents the moon, and the stylized tent repeats elements of the ‘K’ and the ‘A’ in the initials,” explained current KOA Director of Public Relations Saskia Boogman. “Karlo was the one who suggested using ‘K’ for ‘C.’ With that spelling, we had a name that was registrable.” By intentionally misspelling these words, Drum and his associates could copyright the names of not only their business, but also its side activities, like the KOA Kamper Klub.

Originally, the logo background was white, but later on, yellow took over as the KOA color. “President Jim Rogers said, ‘We should live and breathe this color.’ He even had a yellow tuxedo that he would wear to conventions!” Boogman added. Just like brown came to identify UPS delivery vehicles, yellow appeared on KOA shirts, on signage, and even on golf carts and pickup trucks.

Borrowing a copy of the Holiday Inn license agreement, Drum used that basic plan to sell licenses to establish KOA locations to farmers, ranchers, and others with unused land near highways. Their company advertising at the time declared, “If you have, or can lease or buy, small acreage and like to visit with travelers, you can enter this lucrative business.” The idea worked, and in 1964, a Wyoming businessman opened a Kampgrounds of America facility in Cody, the first franchised KOA. “KOA exploded onto the scene,” said Boogman. “They were an affordable way for landowners to start a campground.” Within half a decade, the pair of camps grew into the hundreds, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific.

Working with architects, Drum’s team developed thenfashionable and easily fabricated A-frame buildings for combined stores and offices, with low rectangular wings on each end to house showers, toilets, and coin-operated laundries. A-frame buildings had become highly stylish during the 1960s, after one designed by architect Andrew Geller for a Long Island beach home was featured in the New York Times. Many Americans associated the innovative designs with vacation areas, and so it was an easy leap to establish the association with KOA. Even when long abandoned or converted to other uses, these distinctive structures remain — to this day — easy to identify as former KOA official offices.

A Man’s Man

In 1966, Drum, more an idea man than a manager, hired Billings Chamber of Commerce director Darrell R. Booth as executive vice-president and handed off day-to-day management to him. Booth was well-liked, smart, handsome, and loved outdoor sports — he actually preferred backpacking to amenities such as what KOA offered — and was thought of as a “man’s man.” He also brought business experience and expertise and oversaw early exponential growth in the chain through to 1971. When Drum and his partners founded Kampgrounds of America, their profits came mainly from selling franchises, but during Booth’s able direction, royalties from franchisees became the principal corporate income stream. In 1969, the company went public. Drum cashed out in 1975, selling his shares, and left the company.

But the 1970s brought the oil shortage with consequent curtailment of traveling for pleasure as motorists worried where they could next fill their fuel tanks. “Some franchisees put in gas pumps to ensure that their customers could buy fuel. They had to do something,” explained Pat Hittmeier, 38-year veteran of Kampgrounds of America (KOA) management. Inflation was high and so were interest rates. Then the decade of the ‘70s delivered yet another blow to the company — Booth became ill with cancer in 1979 and died the following year.

A Fresh Start for KOA

In November 1980, a Chinese-born American financier named Oscar Tang purchased Booth’s major stake in the company and took it over. Art Peterson, an actual camping enthusiast and decade-long KOA employee who had set up KOA’s merchandising and equipment division, was named president. Taking KOA private, Tang avoided shareholders’ focus only on profits as a measure of success.

As KOA Kampgrounds had popped up all across the country for almost two decades, the company had struggled to balance growth with maintaining customer expectations. “We needed to provide quality assurance, which was never easy when independent franchisees owned each location,” Boogman explained.

Into the 21st Century

To that end, in 1981, Pat Hittmeier, a young man with a forestry degree and experience wholesaling out lumber, was hired. “I don’t think that they did [maintain quality],” Hittmeier said. “You had hundreds of campgrounds built every year. Sales of franchises was the source of corporate income. In the aftermath, there was a scouring of the system to remove inadequate facilities and under-management. There were properties [franchises] that were sold that shouldn’t have been. [But] in time, royalties became the income stream for the company.” KOA put Hittmeier to work shutting down the sites with poor management and even poorer standards of service. Hittmeier was smart, efficient, and loyal, and he would stay with KOA for nearly 40 years, eventually becoming KOA’s fifth president.

As badly as the ‘80s began, under Peterson’s leadership the decade undeniably went out on a high note, with 900+ campgrounds — KOA’s peak. Peterson’s pet project during his 20-year tenure as CEO was the re-introduction of the Kamping Kabin concept. “KOA always looked for the next thing we could do. Kamping Kabins began in the 1980s. We used these cabins increasingly, but now Deluxe Cabins are growing in popularity,” Boogman explained. “It [glamping] is popular because it is an approachable way to introduce families to camping, which is intimidating to many. We are leaning into it, as are our franchisees. Some are even trying things like yurts and Conestoga wagons to create rich experiences.”

This development truly encompasses luxury enjoyment of the outdoors. Reflecting on these phenomena, Hittmeier remarked, “What’s true of human nature . . . is the more you give people, the more they want.”

The demographic of the typical camper was beginning to change by the 1990s as more and more vacationers could afford RVs — or deluxe cabins, boosted by the aging Baby Boomers generation. “The cabins gave people somewhere to sleep other than in a tent. It took a long time to get momentum for the camping cabins. They morphed into log lodges with bathrooms,” Hittmeier explained.

Destinations

“Travel at the time was really important in building and sustaining the concept of car camping. Unlike in Europe, the

United States had national parks, interstate highways, and Disneylands,” said Hittmeier. “Destinations for families were the key to the growth of car camping.” In 2000, Art Peterson retired after two decades of expanding the company’s focus, and Oscar Tang recruited Jim Rogers from his position as vice president and general manager at Harrah’s RVers flocked to KOA for electrical hook-ups and other amenities. Casino in Reno to succeed Peterson. Rogers, from a loyal Boy Scouts of America and Eagle Scout family tradition, was passionate about camping and getting people outdoors. Under Rogers’ leadership, KOA concentrated on what it knew best — the family-oriented campground — and began to disengage from their international projects, Canada being the exception, and from their RV storage and other offshoot businesses. Rogers, both visionary and experienced camper himself, knew that this policy would improve relations with both their franchise holders and ultimately their guests. When Rogers was ready to retire in 2015, Pat Hittmeier was ready to move into his place after already putting in 34 years with KOA in various management roles. Hittmeier continued Rogers’ emphasis on the guest experience. But in 2019, Hittmeier too retired from the campground business to have time to go hiking, boating, and fishing himself. He handed the KOA reins to Toby O’Rourke, a KOA employee since 2011, who became just the sixth CEO of the company and the first female in the top leadership role. In the three years since O’Rourke has been at the helm, camping has experienced a fast downturn followed by a boom. Thousands of families continue to discover the shared outdoor pleasures of camping. While many have headed into wilderness areas on backcountry trails, even more have sought healthy distances from other travelers inside their own RVs or by tent camping in public and private facilities. “During the second half of 2020 camping fared very well,” Boogman said. “Fall [of 2020] was a record season, and 2021 continued the momentum.” Boogman wasn’t kidding. 10.1 million households were reported to have camped for the first time in 2020 — five times higher than in 2019. For decades, the roadside camping experience was never looked upon as the culmination of one’s trip, but what began as a necessary overnight stop in a random roadside park or field grew into a specified campsite in a campground with electric hookups. Kampgrounds of America — that yellow-labeled, intentionally-misspelled, amenity-laden campground company — proved that they weren’t just a part of the journey. The KOA isn’t always just a stopover, but also a destination, thanks to the big ideas of Dave Drum — and Americans’ thirst for the road trip.

BRIDGE OVER PRYOR CREEK

Route 66 is home to many bridges, some abandoned, but some still functioning, their survival serving as a testament to the rich history of the original alignments of the Mother Road. Particularly historic among these structures is the Pryor Creek Bridge, which nestles into a secluded spot amid overarching trees in Chelsea, Oklahoma. This single span, 123-feet-long and 19-feet-wide steel through truss bridge, was part of the original alignment in 1926 and has stood intact for nearly a century. From its original function as a route of passage to its current status as a historical landmark, the unique history and structure of the Pryor Creek Bridge has solidified it as a beloved Route 66 landmark, open to pedestrians and tourists from all corners of the world.

The history of the Pryor Creek Bridge began in 1926, when the Oklahoma Highway Commission approved the construction of a crossing over Pryor Creek, to be completed by a father-and-son partnership in Chelsea, known as E.G. Fike & Son. The bridge quickly became an integral part of the Mother Road. However, by the 1930s, increased traffic on U.S. 66 and developing engineering standards necessitated the construction of a new alignment of Route 66 in 1932 which bypassed the Pryor Creek Bridge and removed its status as a relied-upon mode of travel. Since then, the bridge has stood open for pedestrians and curious travelers just south of the 1932 alignment. Despite its short-lived period of use, the crossing has been cared for by members of the Oklahoma Historical Society for decades, and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2006. The Pryor Creek Bridge has an origin story similar to that of several other bridges across the Plains states that have since become major Route 66 landmarks. With that said, the significant preservation efforts put in on behalf of this particular bridge begs the question — what is it that makes the Pryor Creek bridge stand out?

A possible answer to this question lies in the story behind the bridge’s design structure — specifically, the use of the modified Pratt Truss design in its construction. First conceptualized by Thomas and Caleb Pratt in 1844, the Pratt Truss design was used heavily throughout the 19th Century. In its incorporation of both wood and iron support structures, this design enabled 19th and early 20th Century bridges to span great distances and withstand heavy loads using simple construction techniques. Hundreds of bridges across the country were engineered using this design, up until the aftermath of World War II, at which point many of them were no longer used. The Pryor Creek Bridge stands as the only unchanged example of this modified design in Oklahoma.

“These bridges are slowly being demolished and replaced for modern vehicular traffic,” said Lynda Ozan, a Historic Preservation Officer with the Oklahoma Historical Society. “So, the fact that this one is still intact, it really is an excellent example of that rare vanishing resource found in Oklahoma. It was part of the original alignment, early in the process, and it’s located in an area where you don’t see a lot of alterations through time, so the bridge remains intact and has that unique charm that a lot of the other resources don’t have.”

As with many other surviving attractions, the quiet endurance of the Pryor Creek Bridge continues to charm curious travelers and contribute to the powerful spirit of today’s Route 66 experience. There is something soothing and surreal, standing on the iconic bridge that once ferried so many travelers, and watching as turtles swim in the waters below and the lush forest — home to a plethora of birdlife — comes alive and showcases the serene, scenic experience that this little corner of Oklahoma’s Mother Road offers.

A SHOUT FROM THE ROAD

A SHOUT FROM THE ROAD

American roadside signage originated in the 1830s, but it surely hit its peak in the mid-20th Century, with unforgettable classics like Coca-Cola’s “Pause that Refreshes” or Coppertone’s “Fastest Tan Under the Sun.” Iconic images and necessarily terse, catchy text cemented modern products in the minds of motorists zooming by thousands of billboards advertising everything from restaurant chains to tobacco to gasoline brands. But leased billboards weren’t the only signage that offered enough real estate on its surface for a really big advertisement — the huge walls of roadside barns also became a recipe for advertising success.

The establishment of barn advertisements along 20th Century highways originated with a unique cast of characters, including brothers Aaron and Samuel Bloch, owners of the Bloch Brothers Tobacco Company, who in 1925 devised a plan to insert their catchy logo into the minds of traveling consumers. The Bloch Brothers hired crews of “barnstormers” to traverse busy roads in Syracuse, New York, looking for available barns on which to paint their advertisements.

Each crew was assigned a specific territory to search for available barns; they would travel to a town, secure a barn location, and stay a couple weeks until their business was complete. In exchange for a payment of 1 to 2 dollars per month, a free paint job, and a supply of tobacco products, farmers allowed the barnstormers to paint the road-facing sides of their barns with a Bloch Tobacco Company advertisement. Known as “Mail Pouch Barns,” they were typically hand-painted in black or red paint, with yellow and white lettering spelling the logo “Mail Pouch Tobacco.” The most memorable line, however, was the company’s catchphrase written in white just below — a subtle reminder to “Treat Yourself to the Best,” which engraved itself into the minds of thousands of Americans.

The Bloch Brothers’ high-impact campaign quickly spread from Syracuse to the rural backroads of Ohio and West Virginia, and eventually throughout the Midwest. By the mid-1960s, there were about 20,000 Mail Pouch Barns spread across 22 states. The significance of the barns evolved from a quirky advertising campaign to a status symbol for American farmers.

“At first, the farmers were happy to get at least the free paint job, but later on, it became nostalgic to have them,” said William Simmonds, Ohio-based author of the 2004 book, Advertising Barns: Vanishing American Landmarks. “Eventually, the farmers were hoping to have a sign painted.” Other companies picked up on the success of the Mail Pouch Barn advertisements, and roadside barns throughout the country soon displayed ads for a variety of products.

In the 1930s, promoter Lester Dill began to use the same approach to advertise his Meramec Caverns attraction in Stanton, Missouri. Dill would offer to paint a farmer’s roadside barn “for free,” as long as they were allowed to cover one side or the roof with what came to be an instantly recognizable advertisement for Meramec Caverns throughout the Midwestern and Plains states. The gimmick was a quick hit.

Just as important as the Bloch Brothers and Lester Dill behind this phenomenon, however, is the legacy of one man who became famous for painting a record number of barn advertisements. Harley Warrick was an Ohio-based painter born in 1924 that developed a reputation for the speed and skill with which he could paint Mail Pouch Barns. Warrick did not use a straight edge to paint the advertisements and reportedly could complete a paint job in under six hours. After being hired by the Bloch Brothers in 1946, Warrick is estimated to have painted or retouched almost 20,000 barns. Those are a lot of adverts.

Warrick, the Bloch Brothers, and the other “barnstormers” involved in the Mail Pouch Barn project had found nationwide fame and success by the mid-1960s. However, disaster struck when, in 1965, Congress passed the Highway Beautification Act, which regulated and removed billboards and other advertisements from the sides of federally-funded highways. “Anything that was within 660 feet of a federal highway was subjected to this rule”, said Simmonds. “President Johnson wanted to clean up the scenery, so a lot of the barns disappeared at that time.” Under this legislation, some farmers were forced to paint over the advertisements or abandon them completely. Soon after, in 1969, the Bloch Brothers Tobacco Company was sold to the General Cigar and Tobacco Company, bringing a swift end to their barn-painting campaign. Warrick continued to work on the project though, touching up existing barns until his retirement in 1992; but despite his efforts, many of the original barns fell into disrepair, sadly emphasizing the loss of their cultural significance.

However, the story of these advertising barns and the practice behind them did not end in the 1960s. Ten years after the original Act was passed, public demand produced an amendment which exempted the barns due to their historic and nostalgic nature. While many of them have flown under the radar since then, local efforts at preservation and a resurgence of the barn-painting practice has continued. In Belmont, Ohio, another artist named Eric Hagan has followed in Warrick’s footsteps. Hagan has dedicated himself to continuing Warrick’s legacy. He has painted over 600 barns throughout rural Ohio and has helped in getting Warrick’s original barns designated as historic Ohio Landmarks.

Simmonds, another Ohio native, has also played his own role in preserving the cultural memory of these barns. “There used to be a barn located near me, and it got torn down one day. Whatever the reason was, it got me wondering if I could go and find more of those barns,” said Simmonds. “So, I contacted the Mail Pouch Company, and they sent me a list, and I just went after it. My wife and I ended up putting 45,000 miles on my car, and we just had fun with it. We’d make a vacation out of it and travel the backroads, taking pictures of the barns.”

Contemporary Midwesterners like Simmonds and Eric Hagan have worked to honor the efforts of figures like Warrick and the Bloch Brothers, all in the service of preserving the memory of these barns as roadside cultural touchstones. In fact, the impact of this phenomenon is also still visible on the Mother Road, where here and there, along stretches in Illinois and Missouri, a Meramec Cavern barn still stands.

Since most of these barns have disappeared or fallen into disrepair, the survivors have become cultural landmarks, prized by contemporary travelers hoping to spot a few examples of this colorful part of their history. Even via a swift drive-by, the advertising influence and cultural significance behind these barns continues to strike modern road travelers, reminding them, via the power of advertising, to continue to “Treat Yourself To The Best.”

Bruce HORNSBY

When driving past all the roadside towns, attractions, and curiosities that the Mother Road has to offer, it is essential to also have the perfect road trip playlist to accompany a journey. Whether its classic rock, country, or quintessential Americana tunes, the perfect driving song can help to enhance the Route 66 experience for any traveler. There are some musicians that seem to embody this spirit perfectly, with an arsenal of songs behind their belt that would make perfect additions to a Route 66 playlist. One of these artists is none other than American singer-songwriter Bruce Hornsby, who has created countless anthems both individually and collaboratively throughout his forty-year career. Following a longer conversation with Brennen Matthews, learn more about Hornsby’s likes, dislikes, and pieces of life advice in this parting shot interview.

What is the most memorable place you’ve visited in America? The Lorraine Motel in Memphis, TN. What did you want to be when you grew up? I wanted to be Bill Bradley of the Knicks. Who has caused you to be starstruck? Governor Gerald Baliles of VA. What characteristic do you respect the most in others? Empathy. Dislike in others? Lack of empathy. What characteristic do you dislike in yourself? Occasional solipsism. Who would you want to play you in a film based on your life? Judge Reinhold. Talent that you WISH you had? Dancing. Best piece of advice you’ve ever received? Be a tough self-critic. Best part about getting older? Learning from mistakes. What would the title of your memoir be? Slow learner. First music concert ever attended? Peter, Paul and Mary at William and Mary Football Stadium. What is your greatest extravagance? My house is too big. What is the weirdest roadside attraction you’ve ever seen? The Coffee Pot House outside Lexington, VA. If you could change one thing about yourself, what would it be? Cognition and Retention. What do you consider your greatest achievement? Still having a creative career 36 years later. Most memorable gift you were ever given? The gift of relative pitch. What is the secret to a happy life? Being able to do what one loves most, for a living. What breaks your heart? Poverty and narrow-mindedness. What is the last TV show you binge watched? Ozark. What is your favorite song (of your own)? Maybe “Cyclone.” What is your favorite song from someone else? “Like a Rolling Stone” by Bob Dylan. What is still on your bucket list? Playing all of the modern classical pieces I work on, well. What do you wish you knew more about? Physics. What is something you think everyone should do at least once in their lives? Try stand-up comedy. What fad or trend do you hope comes back? Disco. Strangest experiences while on a road trip? At two in the morning on Interstate 85 in the top of North Carolina, seeing a seven-foot tall man in a loincloth dancing in the middle of the road in freezing weather. My brother Jon saw him too. What movie title best describes your life? Mr. Blandings Builds his Dream House. Funniest celebrity you know? Ariel Rechstaid. Ghost town or big city person? Ghost town. Lake or ocean person? Lake. What does a perfect day look like to you? Hanging with family. What would your spirit animal be? A Nutria. Which historical figure — alive or dead — would you most like to meet? Don Delillo. What meal can you not live without? Ballpark sushi. Bizarre talent that you have that most people don’t know about? Splitting my fingers into pairs, back and forth. What surprises you most about people? Their capacity for idiocy. What makes you laugh? Larry David. What do you think is the most important life lesson for somebody to learn? Be kind. What is one thing you have always wanted to try, but have been too afraid to? Yahtzee. What do you want to be remembered for? Having made some things that were worthwhile.