34 minute read

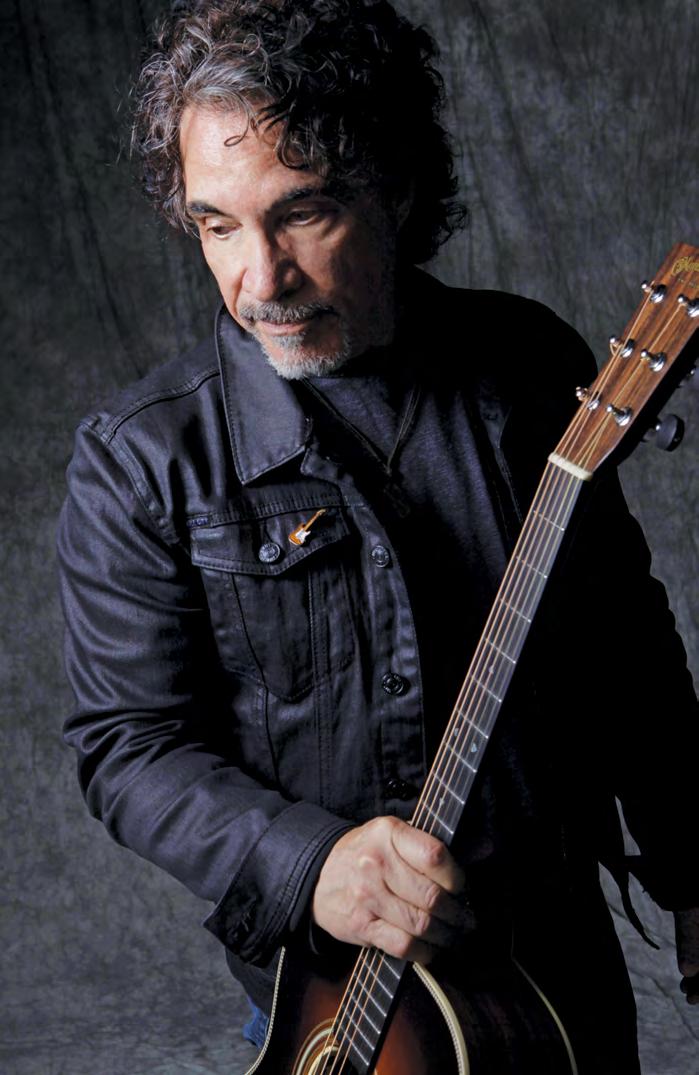

A Conversation with John Oates

Hall & Oates

Advertisement

By Brennen Matthews Images by Jeff Fasano

As a young teen, my evenings and Saturday mornings were spent glued to the radio, anxious to discover and enjoy the myriad of amazing music that flowed from the airwaves. It was the ‘80s and iconic music was being born. Radio offered a diversity not witnessed before and the poppy sounds of hit artists like Madonna, Michael Jackson, and Phil Collins influenced young and old across the world, ensuring commercial success. There were many fantastic artists in those golden years, but one group seemed to dominate the charts: Daryl Hall and John Oates, aka Hall & Oates. Week after week, their tracks ruled every mainstream countdown. It was impossible to turn on the radio and not hear their music. Hit songs like “Kiss on My List,” “I Can’t Go for That,” “Maneater,” “Out of Touch,” and “Private Eyes,” found a firm home at #1, and the duo constantly hit the road to tour the world. In 1984, the Recording Industry Association of America announced that Hall & Oates had surpassed the Everly Brothers as the most successful duo in rock history, earning a total of 19 gold and platinum awards. They were on fire. And then suddenly, surprisingly, by 1986, Hall & Oates went relatively quiet. Hall went on to pursue a solo career and Oates made some major life changes that led him down new and impacting paths. Yet still, their huge hits lived on in video and radio for us all to enjoy. Now, in 2022, I still constantly hear Hall & Oates when I am scrolling through the channels, and their smooth sounds bring back vivid, wonderful memories from a period of time now long gone.

You were born in New York, but moved to Pennsylvania when you were about four, due to your dad’s job. You would have been in your early 20s during the Summer of Love era that was going on in San Francisco and in New York. Did you experience that whole movement in Pennsylvania/Philadelphia?

I mean, yeah, sure, there was kind of a quasi-hippie culture in downtown Philadelphia which Daryl and I were kind of part of. I don’t think we, together, ever really considered ourselves to be hippies. But we were part of, you know, being young, being in your late teens, whatever, early twenties, adopting the style, the kind of mentality of the times— we were definitely in on all of that. I remember there was a “Be-In” in Fairmount Park in Philadelphia. I can’t remember the bands who played, but I remember going there. It was kind of like what happened in San Francisco, the Philadelphia version, a year later. It was kind of a cultural social thing that was sweeping the country with young people and of course centered in the urban areas. We were part of that, but I don’t think we ever bought into it completely. Daryl and I thought about moving to the country and living on a farm, you know, getting back to the land. It was the era of the singer-songwriter.

So, I guess it affected us in a way, but at the same time, we both came from an R&B tradition as well, much more musically sophisticated and kind of sharkskin suits and band arrangements, and horns, and strings. We had our foot in two worlds and I think we’ve always kind of been like that if we’re talking about Hall & Oates.

You joined your first band when you were quite young...in grade eight?

when I was about in 8th grade and continued all the way through high school. We recorded a song [“I Need Your Love”] the year I graduated from high school in the summer, which was a song that got played on Philadelphia radio and then, of course, simultaneously Daryl was recording a song with his doo-wop group that was also being played on the radio. It kind of drew us together in a strange way, we knew of each other, we were aware of each other, and then we finally met.

At that young age, what was it like the first time you heard yourself on the radio?

I remember I was parked on a country road in Pennsylvania with my girlfriend at the time. I like to say that whatever we were doing at the time, I stopped doing it and paid attention to the fact that it was on the radio. It was a big thrill. To be a teenager, to hear yourself on the radio, it was a big deal. It was definitely a moment in my life where I thought that things could change.

Did you guys actually have a record deal at that point?

Well, we sort of had a record deal. We made the record at a place called Virtue Sound on North Broad Street in Philadelphia. The guy who owned it was Frank Virtue, who had a band called the Virtues. They had an instrumental hit called “Guitar Boogie Shuffle.” That’s what put him on the map. He had a very small, funky, little studio. We saved our money, and went in, and recorded the song. In those days, you would record a song and you would get what was called an acetate, which was an actual vinyl record that would be literally etched and cut with a stylus in the studio. You could only play it x amount of times before it would wear out since it was all vinyl. So, we had this acetate and we went down to Chestnut Street in Philadelphia. There was a really great shop called the Record Museum that specialized in vinyl. Well, that was the only thing that existed then. They specialized really in 45s, really offbeat, obscure 45s from doo-wop groups and B-sides, and things like that. It was just a very cool place to go. I used to go there all the time just to buy records.

So, we went into the Record Museum with our acetate under our arm. I said to the guy behind the counter, ‘Hey, we made a record. You wanna hear it?’ and the guy went ‘Yeah, sure,’ and he took it and literally put it on the 45 player right there behind the counter and played it, and he said, ‘Oh, this is cool. What are you guys doing?’ and I said, ‘I don’t know, we’re trying to put this record out,’ and he said, ‘Come on back into the office.’ And we went back and signed a contract. Of course, without consulting a lawyer or anyone else which would be a portent of things to come in my very well-documented crooked career of dealing with the music business.

So, the record came out on Crimson Records. Crimson Records was this little custom label that was owned by the Record Museum. The only other release that I’m aware of is “Expressway to Your Heart” by The Soul Survivors, which was actually on Crimson Records, as well.

After high school you joined Temple University to study journalism.

Yeah, I studied journalism because it was the path of least resistance for me. I was a writer, I always thought of myself as a writer. I was always good at writing. Whether it be prose,

or songs, or whatever it might be. It just has always come naturally for me. So, when I got to college, I didn’t know what to do, so I literally did what was easiest. It kept me out of the Vietnam War by college deferment, and also was easy, and I could spend a lot of time doing music on the side.

I have read different iterations of how you and Daryl actually met. What’s the real story?

You know, in those days, the DJs from the various stations would hold record hops, which were teenage dances basically for kids in the Philadelphia area. There was a guy named Jerry Blavat — “the Geator with the Heater,” one of the DJs from WDAS which was one of the premiere R&B stations. [The station] that was playing both Daryl’s record and my record had a record hop in West Philadelphia at a place called the Adelphi Ballroom. The DJs would ask the various artists to come and lip-sync their songs to make a guest appearance at these record hops. It was kind of part and parcel of getting your record played. It was kind of a free version of payola. We’ll play your record and you got to come and perform at our dance basically. So, Daryl’s group was independently asked to do it, my group was independently asked to do it, but we didn’t know each other.

We were all kind of sequestered in this little area because it was kind of a social hall, I guess you could call it a banquet hall, where they’d clear out everything and the kids would dance, and the DJ would play records. We were all in the back in the little kind of holding area. Before any of us went on, a gang fight broke out among the kids in the crowd, so we basically jumped in the service elevator and went down to the street level and that’s how we met. Sounds too good to be true right?

So how did you and Daryl end up connecting musically, because after university you ended up setting off to travel around Europe for a little bit.

That was the summer of ‘67 into ‘68. After the [Adelphi Ballroom] happened, Daryl and I just kind of palled around. We shared an apartment for a little bit and then we lived in different places separately. He was doing studio work and playing with a bar band at night. I was playing in folk clubs and various blues bands around the city, but we weren’t working together. We were just hanging out here and there or not. When I graduated from college in 1970, one of my dreams was to travel through Europe. So, I sold everything I had and took off with a backpack and a guitar and I went to Europe. It was a thing that kids were doing in those days. I subletted my apartment to Daryl’s sister, and her boyfriend, and I took off for four months.

When I got back, there was a padlock on the door. They hadn’t paid the rent, so I literally got back with no money and a backpack and guitar and was standing on the street. So, I went down to where Daryl was living at the time and I said, ‘Hey, your sister didn’t pay the rent. I’m locked out of my apartment,’ and he said, ‘Why don’t you just sleep in [my] upstairs bedroom?’ He had this little, tiny “Father, Son, Holy Ghost” house, which was a three-story house with one room on each story. They were former slave quarters back in the 1700s or whatever, in the downtown historic area of Philadelphia. So, I moved into the upstairs bedroom that had a fold-out couch to sleep on. That’s where Daryl’s electric piano was. Every day he would come up to noodle around on his piano, and there I’d be, sitting on the couch with a guitar. He was not happy with what was going on musically with what he was doing, and I really didn’t have much going on [either], because I’d just gotten back from Europe. So, we started to write songs together. We started taking it seriously and seeing that it might be a viable thing for the two of us to do. We played a few art galleries, coffee houses, things like that, and the response was always very positive. Little by little, it grew, and we realized that we might have something that might be something.

In late 1971, you guys signed with Atlantic Records. Many aspiring musicians send in demos to A&R and never hear back. What was the process like for you guys to get signed by Atlantic?

We were associated with a guy in Philadelphia who was a famous songwriter, producer from the late ‘50s and ‘60s. We would record some demos, this guy would represent us, but we never got any response, it was always negative. And then we decided to try to do some showcases in New York City, because we were doing some recording sessions as studio musicians. So, we’d go to New York, and we’d play a showcase at these various venues. People would come up to us after the show and rave about us and say, ‘You guys are amazing! Oh, we love you, we love you,’ and a week or two would go by and we’d say, ‘Hey, what happened?’ and he’d say, ‘Oh, they passed.’ It was always, ‘they passed,’ and we couldn’t figure out why.

Later on, we realized that what he was doing was basically demanding so egregiously from these various companies that seemed to like us, that they all just said, ‘These guys aren’t worth dealing with, let’s just forget about them.’ We didn’t know that we were being basically misrepresented. We kind of figured it out after a little while and we were so frustrated, we said we need to try to do something different.

So, we pulled a little bit of money together and we bought fake student half-fare flights to Los Angeles. Back in those days, if you were a student, you could buy an airplane ticket for half-fare if you could prove that you were a student.

So, we brought our old student I.D. cards, because we were both out of college at the time, and we convinced the guy that we were still in college, and the guy gave us half-fare tickets and we flew to Los Angeles. During that period of time there was a publishing company that we were associated with vis-à-vis this guy in Philadelphia, Chappell Music, now Warner Chappell, and because we didn’t know anyone in Los Angeles and we didn’t know what to do, we reached out to a guy that we had met during this ill-conceived showcase adventure. We said, ‘Hey, we’re coming to Los Angeles,’ and the guy said, ‘I’ll pick you up at the airport.’ And this guy picked us up at the airport, we didn’t really know him that well, he worked for Chappell Music, and he picked us up and he said, ‘You can sleep at our house.’ So, we went to this guy’s house, and we just crashed there for a little bit, and then we checked into a place called the Tropicana Motel on Santa Monica Boulevard which was a classic ‘60s rock n’ roll hotel. They had this little coffee shop called Duke’s, and I think Jim Morrison pissed on the table or something like that. But anyway, it was that period of time in L.A.

We didn’t realize that in L.A. you needed a car, and we didn’t have a car. So, there we were in this hotel on Santa Monica Boulevard and the only thing we could do was walk to the International House of Pancakes that was about a four or five block walk, and that was about as far as we could get without getting arrested.

So, we did that, and this guy said, ‘I’ve got a guy that you should meet.’ I guess he was independently wealthy... He was an art dealer and very good personal friends with Ahmet Ertegun at Atlantic Records. So, he took us over to this little bungalow in West Hollywood and the guy had this kind of garden, a backyard with trees and plants and flowers. So, we went there, and we literally brought a little electric piano, and I had an acoustic guitar, and we sat in this guy’s backyard, and we played some songs. I remember this was the unique part of it — he started laughing after we played a few songs, and we weren’t sure exactly what was happening. I remember he said, ‘Are you guys for real?’ And I thought he thought we were mocking him or something and we were like, ‘Yeah, this is what we do,’ and he’s like, ‘Why don’t you guys have a record contract?’ and we said, ‘Well, because we don’t,’ and he goes, ‘Well, you do now.’ And he called Ahmet Ertegun and said, ‘You have to hear these guys, these guys are amazing.’ His name was Earl McGrath.

Anyway, he had made arrangements for us to go back to New York and audition for Atlantic Records based on his endorsement. So, we went into a little room in Atlantic Records with Arif Mardin, Jerry Greenberg who was the President, and Tommy Mottola who, at the time, also worked for Chappell Music. At the end of the audition, Arif Mardin said, ‘I want to produce these guys,’ and that was all it took, because Arif Mardin was a god then at Atlantic Records. And that’s how it started.

You guys then ended up opening for David Bowie during his Ziggy Stardust Tour. Were you fans of his music?

We were both fans of his Hunky Dory album, the album that preceded Ziggy Stardust, because he was doing kind of what we were doing. It was very artsy, acoustic, you know singersongwriter in style. Little did we know that he was going to make a 180 and become this spaceman from Mars. We actually didn’t know that when we got the gig as his opening act. It was in Memphis, Tennessee, at his first show on his American tour, and we had no idea what he was going to do. We assumed he was doing Hunky Dory-type music, and we thought that’s why it would fit based on what we were doing, because we were very acoustic at the time. Then, of course, I remember we did our show and then I went out into the house to watch him, because I wanted to see him play, and all of a sudden strobe lights and smoke and this creature with red hair and giant platform shoes appeared, and it became this entirely different thing. To be honest with you, I was shocked, and I was blown away. I think what I was really blown away with was the fact that someone could actually do that. They could be one thing and then be something completely different. I think that was inspiring for me and Daryl. We said, ‘We can do whatever we want,’ and we had no mandate to continue to do what we were doing because our record wasn’t successful. We didn’t have a hit record or anything like that, so we just thought, ‘Well, we can do whatever we want,’ and of course, I think that mentality has carried over through our whole career.

“She’s Gone” was only moderately successful when it was first released as a single in 1974, but then found huge traction when it was later released as a remixed version. What is the song’s backstory?

I was hanging around in downtown New York in the [Greenwich] Village going to the Mercer Art Center, going to the clubs and things like that, just really immersed in the New York downtown life. There was one night, I guess it was December of ‘72, probably. I was down there, it was the middle of the night, very late, there were very few things open. There was a place called the Pink Tea Cup, which was a soul food restaurant on Bleecker Street that was open all night. One of the few places. I was in there and this gal came in and she was outrageously dressed in a pink tutu and cowboy boots, and it was freezing cold. We just started hanging out. In the style of the ‘70s, things kind of happened fast in those days.

We saw each other a few times and then I asked her if she wanted to get together on New Year’s Eve and she said yes. New Year’s Eve rolled around, and she never showed up. So, I sat on the couch and pulled out my guitar. In my mind, I was thinking, ‘Well, if she’s not coming tonight, she’s never coming.’ I started singing ‘she’s gone, oh’ and it was kind of this folky lament, I guess you’d call it, and it never went any farther than just that little hook idea. Then Daryl came back a few days later, we were sharing an apartment at the time, I don’t know where he was, but he was somewhere, and I played it for him, and he sat down at the piano and immediately started playing. It just kinetically happened. You know, he played the classic piano riff that you hear at the beginning of the song and that was the catalyst to start the song, and then we just wrote it, we wrote the whole song in probably an hour and a half.

Your first three albums Whole Oats (1972), Abandoned Luncheonette (1973), and War Babies (1974) were with Atlantic Records. Then you moved to RCA Records for your fourth album, which produced your first Top 10 hit, “Sara Smile.” That song really hit hard. How did that impact your lives at that point?

Well, we had three hits in a row. We had “Sara Smile,” “She’s Gone,” and “Rich Girl.” All at the same time, ‘75 and ‘76. It took us from playing in clubs right into playing in arenas,

immediately. That was the mid-’70s. Then, in the late ‘70s, we had a bit of a lag, a little bit of a dip, we didn’t have any hits on the subsequent albums after “Rich Girl.”

There were three albums that came out and none of them had any real hit records. We had been recording in L.A. in the mid-’70s, during that period of time, and we weren’t satisfied or very comfortable recording [there], we wanted to get back to New York and record there. So, we used this downturn… we kind of went from the clubs to the arenas and then went back to the clubs, or the small theaters, and during that period of time, we realized that what was missing was the fact that all the subsequent records prior to the ‘80s were made with studio musicians and not our live band. We had two different worlds going on; we had a live band that we would perform with, but we never felt comfortable enough to take into the studio, and we’d go into the studio with studio musicians, but we knew that wasn’t the answer. So, as the end of the decade approached, we focused on trying to develop a live band that was good enough to take into the recording studio. We went through a bunch of different configurations of players and that culminated in the ‘80s band that we finally found. We made all our records in the ‘80s with that band, and we began to produce ourselves, and that was the key to the success that we had in the ‘80s.

What was your writing process like? Did you write the lyrics together or separately, and then come together?

One of us would always initiate something and then the other person, depending on the situation... let’s put it this way, there were no hard and fast rules. Whatever happened, happened. Daryl would write a song… like “Rich Girl,” he wrote it himself. Or someone would come up with an idea and we would function to write together, like a collaboration, or we would function almost like editors, where one person really had a handle on the song, and it wasn’t really a collaboration as much as the other person was giving an objective opinion like, ‘Oh, well try this,’ or maybe, ‘What if this part was here,’ and then we would collaborate a lot on the lyrics. That’s where most of our collaboration happened — on the lyrics.

Then, enter the 1980s and you had a string of successful albums with a new soft-rock soul sound: Voices (1980) — featuring “Kiss On My List,” “You Make My Dreams,” and “Everytime You Go Away.” Then Private Eyes (1981), and H2O (1984) which had your longest-lasting No. 1 hit “Maneater.” From 1981 to 1985 you had twelve top 10 hits and five #1 singles. At what point during this time did it hit you that you had really ‘made it?’

All I remember in the ‘80s was being completely consumed with demands. Demands for time. What people, I think, don’t realize is that one of the most important aspects of success is that it’s a demand on your time, your energy, your emotion, and your physical energy. MTV had just started, so now in addition to making records, we had to make videos. And of course, there was touring, and it was never-ending. So, between writing the songs, making the records, making the videos, going on tour, and then starting the cycle over again from late ‘79 right up until mid-’80s, we didn’t stop for a second. In fact, there were no breaks from 1972 until about 1987. It was all-consuming and the ‘80s just ratcheted up the intensity of all that.

Because we had such tremendous success in the ‘80s, I assume people think, ‘Well, that must be your favorite time in your career.’ It might have been one of my least favorite times because, as I said, I couldn’t really enjoy it, because I was so deep in it. My favorite time was the early ‘70s when everything was new, when everything was discoverable, when everything was in the process of becoming. It was so interesting to go to a different city and meet new people and play a show and realize what worked and what didn’t work, and how to change it, and constantly trying to get better.

Did you guys feel a lot of pressure to churn out hits?

There’s always that pressure, yes, without a doubt. In fact, the song “I Can’t Go for That” is exactly about that. That song’s about not being told what to do, not being pressured to do something. I think one of the things I’m most proud of, when you look at the ‘80s hits, or actually any of our hits going back to “Sara Smile,” “She’s Gone,” “Rich Girl,” or whatever — none of them sound like the other one. Not one. And there’s always that pressure, as you said, to kind of follow up your hit with the follow-up single. We never did that ever. Every song is completely different. Which I’m very, very proud of and I don’t think a lot of bands can say that.

An interesting song that does sound very different from a lot of your other stuff that really hit heavy on the radio is “Maneater.” What’s the story behind that song?

I was hanging out in Greenwich Village, it was the ‘80s, very jacked up. If you were in New York City in the ‘80s, you were at the epicenter of that. As a songwriter, you can’t help but be affected by the things that are around you. There was a hangout in the Village that we used to go to, it was kind of a bar-restaurant, and it was full of actors, models, and musicians. It was the cool downtown scene kind of thing.

There was a girl that was very pretty, in fact, beautiful, who had a really… well, she swore like a sailor. So, to me, the juxtaposition of her great beauty and her coarse personality was very weird. The first thing I thought was ‘she’ll chew you up and spit you out.’ That mulled around in my head, and I remember, I was walking home from the place in the middle of the night, and it popped into my head ‘she’s like a maneater.’ I had just come back from Jamaica, so I began to write this kind of reggae-inspired idea for a chorus based on ‘Woah, here she comes. Watch out boy she’ll chew you up.’ I just sat with that for a while and… interestingly enough, I was writing songs at the time with Edgar Winter, and I went to Edgar Winter’s house, and we were throwing around ideas and I played it for him, but he didn’t respond to it — the reggae thing. It just didn’t move him. So, we moved on and we ended up not really writing anything. Later, I played it for Daryl and he sat down and said, ‘Yeah man, I like the idea, but I don’t like the groove. I don’t think reggae is a cool groove for us,’ and he began to play that Motown feel that you hear on the record, and then we went in that direction with the song.

Around the mid-’80s, you were invited to take part in the “We are the World” soundtrack. How did that come about?

It was cleverly scheduled for the night of the American Music Awards when everyone who was anyone in the world of pop music would be in one place. Nothing like that could ever

happen again. The music world was much more condensed, it wasn’t as crazy as it is now, with multiple award shows. So, everyone was in Los Angeles attending the American Music Awards and Lionel Richie and Michael Jackson wrote the song and a reach out was made through the various managers and agents to come to the studio after the awards were over, and the old cliche sign, leave your egos at the door, managers and agents stay outside. Everyone went in and we recorded the song.

So, the video and the whole recording was done that same night, after the American Music Awards?

Right then. It happened within a few hours. It went pretty late into the night with the solos and stuff like that. The bulk of it, where everyone is standing, singing all at the same time… everyone was on these tiered bleachers. I remember Ray Charles was off my left shoulder in front of me and Bob Dylan was behind my right shoulder. I thought that was pretty cool. Up there on the wall, you see that right there, that framed picture? That’s the sheet music with everyone’s signature on it from “We are the World.” One of my prized possessions. I actually had enough foresight to go around and get it signed by everyone.

Did everything go off seamlessly when recording or were there a lot of takes?

Well, if you think about the type of people — all major stars, people who obviously were very successful doing what they do, all put into one room together with no wardens to keep them in check. You had a lot of people just throwing out ideas, because creative people, that’s what they do. At the same time, it wasn’t their show. I think that was an unusual dynamic to put all these triple A type leaders so to speak, a lot of chiefs, and not a lot of Indians, let’s put it that way. You put them in a room, and they all want to have creative ideas, but at the same time, it was really Michael Jackson and Lionel Richie’s song, and they were kind of running it. I think the reason it came off so seamlessly was because a lot of people had respect for them, first of all, and they were leading the thing. And to have Quincy Jones there, everyone had ultimate respect for Quincy Jones. I think he was the glue. So, no, there was not a lot of takes. You have all these amazing singers, and then you just say, ‘Here’s what we’re going to sing,’ and everyone sang in unison.

How was Michael Jackson to work with?

I had met Michael before; he was very shy and very quiet. He always spoke in that very quiet voice of his. He wasn’t extremely outgoing. But he was dressed to the nines, you know, in his quasi-military garb.

You spent a lot of years on tour. Did any notable crazy things happen?

You don’t have enough time. (Laughs) We were on the road for 50 years! We got robbed at gunpoint in Australia the first time we went there by the Rusty Gun Bandit. We were in a restaurant after the show, the restaurant was empty except for the chef, and his wife, and another couple. And this guy came in with a shotgun, and a ski mask, and wanted our money. He went to this table with the chef… the chef I think grabbed his gun, hit him, and we knocked him down. We pushed him through a plate glass window, the police arrived, we were in all the newspapers. It turned out this guy had been robbing restaurants in that area for a period of time, they called him the Rusty Gun Bandit because his shotgun was all old and rusty.

MTV had a Learjet race which is the height of extreme, absurd excess. Daryl was in one Learjet in New York, and I was in a Learjet in California, and we had contest winners from MTV in the jets with us, and we both raced toward Kansas, the middle of the country. It was just a big, giant promotion. There was just so much stuff going on.

What an amazing experience. In 1986, after having made at least one album a year since 1972, you guys slowed right down. Daryl pursued his solo career and you moved to Colorado to start a new chapter.

Daryl started making solo albums in the ‘70s. He made a number of them. None of which really seemed to have much impact. We’ve always had that kind of thing where we look at ourselves as two individuals who work together. Even more so today than ever before. We have our own lives, our personal lives are different, but we come together, and we play the music that we created together, and that’s good; people want to hear it and that’s fantastic.

When you moved to Colorado, did you have any clear definition of what you wanted, at that point, for yourself?

important thing for me. I was happy that we could break out of that constant rat race, that hamster wheel of writing, touring, recording, making videos — I was done. And I had personal issues: I was getting divorced, we had lost our manager, there were things going on that were just breaking down. And I wanted to change my life. I needed a complete reboot of who I was as a person, and it wasn’t going to happen by me continuing on the same path. So, I had to have a clean break and my going to Colorado was really, for me, a necessity. I didn’t know it at the time, but it ended up being the thing that really changed my life and made me able to continue.

In what way?

Well, because I completely stopped making music and I began to live in the mountains [where] I just associated with a group of people who didn’t care whether I was a musician or not. I started backcountry skiing; I spent a year without a car, riding my bicycle. I started over again, I unplugged from everything I’d done. That led me to meeting my current wife, and having a kid, and building a house, and really changing my life completely. I think had that not happened, who knows where I would’ve been.

After being a famous rock star who played arenas, how would you compare being a dad to all that other worldly success?

I have to credit being a dad to my wife, because if it wasn’t for her, who knows, I might not have ever done it. Then after having a kid, I have to credit Amy again, because she said, ‘You know, if we’re going to be a family, we have to be a family. We have to stick together.’ I had never even conceived of that. If I was going to tour, would I tour with a wife and kid? It was a completely alien concept. Everything I had done prior to that was kind of a boy’s club, really. So, I took a leap of faith and trusted her, and she was right.

We took [our son] on the road at five weeks old, and he was basically on the road with us until he was 13. He started at a boarding school in ninth grade, and went straight through boarding school, right to college, and has basically been living on his own from the time he was 14. I like to think, because we were able to spend his earliest years constantly together, that we created a bond that’s unshakable. Even today, we have a great relationship, even though we don’t see each other as often as we’d like.

The older my son becomes, the more I hear the Harry Chapin song “Cat’s in the Cradle.” Whereas now, we’re older and we want to spend that time with them, they’re busy trying to build their lives.

Yeah, that’s true. That period where they’re going to find themselves from 12 to 20, as a father, you go from being their superhero to the dumbest human being on planet earth. (Laughs) I think it’s necessary, it’s that necessary break. Especially for boys… boys need to assert themselves, need to flex their masculinities in a weird way so they do stupid sh*t that they have to kind of go through. But now, now he’s coming back. For the past few years, he’s definitely come back to actually seeking our opinion on a more adult level, which is great. But you know, he’s his own man, he’s an independent thinker, and that’s what I’ve always hoped he

You’re in your 70s. Has this been a good decade for you?

I wouldn’t talk about it in terms of a decade, but I would talk about it in terms of the last couple of years. For me to be able to reflect, to have time to think about a lot of things. I had a lot of realizations about how I want to deal with where I am right now and how I want to deal with the years going forward. I think as you get older, and you see the horizon kind of getting closer, you start to think about things in a different way. These past two years have really given me a chance to reevaluate a lot of things, and I like to make a little joke — there are no more rehearsals. Time for rehearsals is over. It’s all about the show at this point, the show of life, I guess you’d call it.

You published your autobiography Change Of Seasons in 2017. What inspired you to write the book?

I had done a series of interviews with a guy named Chris Epting who actually grew up in the same area of Pennsylvania that I did — we didn’t know each other. He just seemed to get me. Every time we’d talk, we’d go in directions that we had some kind of commonality. He was a writer who had written a number of books, mostly history books, and I’m a history buff. One day after numerous interviews he said, ‘You’ve got such great stories; you’ve had such an interesting life. You should write a book, and if you ever want to do it, I’d like to help you,’ and that’s how it happened. As we began to write, I began to find my writer’s voice. It took quite a while and he was very encouraging, and he also served basically as an editor and a researcher. He really helped me by researching the past and bringing up a lot of things that I had forgotten about or didn’t have a lot of detailed memory about. So, in a way, it was almost like having regressive therapy, it kind of opened up my past and history of things that I might never have even thought about. I really spent a lot of time on that book, over two years. It was an interesting process to go through. I really enjoyed it.

The hardest thing about that book was to decide, how do I tell my personal story when my personal story [is] so intrinsically wrapped up in the Hall & Oates experience? So, I had to try and separate myself, but I couldn’t ignore a major part of my life, so it was kind of an interesting challenge to do that.

What do you want your legacy to be, what do you want to be remembered for?

I play bluegrass, delta blues, I play jazz, I play ragtime, I play ‘60s R&B, I play ‘80s pop obviously. I don’t think a lot of people can do what I do; play in a musically sophisticated band like Hall & Oates and at the same time I do very roots music, acoustic-based, traditional roots-based music in Nashville with my Good Road band. I’m doing an acoustic tour with a Nashville guitar player named Guthrie Trapp. [I can] pick up a guitar and play roots music from the 1920s and the 1930s in a very authentic way. I think it’s a very unique thing. I would like people to understand [and remember] how versatile I was as a musician.